Background: Abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau is present in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease.

Results: Key kinases that phosphorylate tau at Alzheimer disease-specific epitopes have been identified in a cell-based screen of kinases.

Conclusion: GSK3α, GSK3β, and MAPK13 were the most active tau kinases.

Significance: Findings identify novel tau kinases and novel pathways that may be relevant for Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Bioinformatics, Enzymes, Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3, Tau, Kinase, Phosphorylation

Abstract

Neurofibrillary tangles, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer disease (AD), are composed of paired helical filaments of abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau. The accumulation of these proteinaceous aggregates in AD correlates with synaptic loss and severity of dementia. Identifying the kinases involved in the pathological phosphorylation of tau may identify novel targets for AD. We used an unbiased approach to study the effect of 352 human kinases on their ability to phosphorylate tau at epitopes associated with AD. The kinases were overexpressed together with the longest form of human tau in human neuroblastoma cells. Levels of total and phosphorylated tau (epitopes Ser(P)-202, Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-235, and Ser(P)-396/404) were measured in cell lysates using AlphaScreen assays. GSK3α, GSK3β, and MAPK13 were found to be the most active tau kinases, phosphorylating tau at all four epitopes. We further dissected the effects of GSK3α and GSK3β using pharmacological and genetic tools in hTau primary cortical neurons. Pathway analysis of the kinases identified in the screen suggested mechanisms for regulation of total tau levels and tau phosphorylation; for example, kinases that affect total tau levels do so by inhibition or activation of translation. A network fishing approach with the kinase hits identified other key molecules putatively involved in tau phosphorylation pathways, including the G-protein signaling through the Ras family of GTPases (MAPK family) pathway. The findings identify novel tau kinases and novel pathways that may be relevant for AD and other tauopathies.

Introduction

Tauopathies, including Alzheimer disease (AD),2 frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17, progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick disease, and corticobasal degeneration are all characterized by the progressive development of intracellular inclusions of the microtubule-stabilizing protein tau in affected brain regions (1, 2). The accumulation of misfolded, hyperphosphorylated tau species in AD correlates with neuronal loss and cognitive impairment unlike senile plaque burden (3). These findings have highlighted the need for identifying tau-based disease modifying therapies for AD and other tauopathies.

The primary function of tau is to facilitate assembly and maintenance of microtubules in neuronal axons, allowing transport of cellular cargo (4). Tau function is regulated by phosphorylation as well as by alternative splicing. There are 85 putative phosphorylation sites on the longest tau isoform, and more than 20 Ser/Thr kinases have been shown to phosphorylate tau in vitro. However, there is still uncertainty about which of these kinases actually phosphorylate tau in vivo (for reviews, see Refs. 5 and 6). Mass spectrometric analysis of human brain tissue combined with Edman sequencing and specific antibody reactivity has been used to demonstrate numerous tau phosphorylation sites associated with tau dysfunction and neurodegeneration (6). Many of these are associated with the C-terminal repeat regions of tau, defined as microtubule binding domains, as well as the flanking domains. Site-directed phosphorylation of tau in these two domains is essential for regulating tau function in microtubule assembly and stabilization. In AD brain, abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in these regions is thought to change the conformation of tau and decrease its affinity for microtubules, resulting in microtubule instability and neurofibrillary tangle formation (7, 8). Loss of a functional microtubule cytoskeleton contributes to neuronal cell dysfunction and cell death.

Numerous tau phosphorylation sites are associated with tau dysfunction and neurodegeneration (5, 6). Several groups have used phosphorylation-dependent tau antibodies and a panel of AD cases of varying severity to map epitopes that were associated with different stages of neurofibrillary tangle formation during disease progression (9, 10). Epitopes that were associated with pretangle, non-fibrillar tau included Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-262, and Thr(P)-153; epitopes associated with intraneuronal fibrillar structures include Ser(P)-262/Ser(P)-396, Ser(P)-422, and Ser(P)-214; and epitopes associated with intracellular and extracellular filamentous tau include Ser(P)-199/Ser(P)-202/Thr(P)-205 and Ser(P)-396/Ser(P)-404. Phosphorylation of tau on Ser(P)-262 and Ser(P)-356 in adjacent microtubule binding repeats significantly reduces the affinity of tau for microtubules and renders tau less susceptible to degradation (11). Phosphorylation of tau on Ser(P)-214 and Thr(P)-231 is also reported to reduce the ability of tau to bind microtubules (12). In p25 transgenic mice, significantly higher levels of Ser(P)-235-positive tau relative to those in non-transgenic mice were present, and therefore Ser(P)-235 was considered to be a CDK5-specific epitope (13). Because CDK5 is a well established tau kinase, we included this epitope in our screen. Identifying the kinases involved in phosphorylation of key residues associated with AD will increase our understanding of the mechanisms of tau dysfunction in AD and lead to identification of novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Here, we evaluated the effect of kinases to phosphorylate tau at epitopes critical for the progression of AD (Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-202, Ser(P)-235, and Ser(P)-396/404).

In vitro, numerous kinases have been reported to phosphorylate tau on multiple epitopes (5); however, these may not reflect the situation in a cellular system. Here we report an unbiased approach to study the effect of 352 human kinases on their ability to phosphorylate tau at epitopes associated with AD in human neuroblastoma cells. The kinases were co-transfected with the longest isoform of tau, and their ability to phosphorylate tau at AD-relevant epitopes (Ser(P)-202, Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-235, and Ser(P)-396/404) was measured by AlphaScreen assays. Kinases that phosphorylated tau at one or more epitopes in a statistically significant manner were further validated in a second screen. Using the GeneGo MetaCoreTM pathway analysis software, we identified the mechanisms by which some kinases regulate total tau levels, through inhibition or activation of translation, and the phosphorylation of tau. A network fishing approach using the kinase “hits” identified other molecules putatively involved in tau phosphorylation pathways and suggested the G-protein signaling through Ras family of GTPases (MAPK family) pathway to be a key regulator of tau phosphorylation. In addition, because GSK3α and GSK3β were found to be the most active tau kinases, phosphorylating tau at all four epitopes, we further dissected these effects using pharmacological and genetic tools in hTau primary cortical neurons. The data provide insights into novel targets and pathways for AD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

2N4R tau was obtained from Peter Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). Kinase clones used for the screen were supplied dried in 96-well plates. The kinases were full-length cDNA clones containing native 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions in pCMV vector (OriGene, catalog number FKIB19604).

The total tau (TG5) and phosphospecific antibodies (MC6 (Ser(P)-235), CP13 (Ser(P)-202), CP17 (Thr(P)-231), and PHF1 (Ser(P)-396)) were obtained from Peter Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). Antibodies to GSK3α and GSK3β were purchased from Abcam, and antibody to GAPDH was purchased from Ambion.

shRNA lentiviral clones for GSK3α and GSK3β were purchased from Sigma. Five clones were tested for each target, and the sequence that gave the highest knockdown with no off-target effects was used. The sequence of the GSK3α lentiviral shRNA used in this study was GTGCTCCAGAACTCATCTTTG, and the GSK3β lentiviral shRNA sequence was CCGGCATGAAAGTTAGCAGAGAT. Non-target (scrambled control) had the following sequence: CAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA.

Cell Culture

SK-N-AS human neuroblastoma cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 1% non-essential amino acid minimum essential medium, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum.

Primary cultures were made from cortices of hTau fetal mice (embryonic day 18) (Taconic/Charles River Laboratories). These mice are C57/Blk6 mice expressing human microtubule-associated protein tau (14) and were obtained from Peter Davies. Neurons were dissociated by incubating dissected cortices in trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) for 2 min at 37 °C. Cells were resuspended in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 supplement (Invitrogen) and glutamine, triturated, and centrifuged at 200 × g for 2 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in Neurobasal medium and filtered through a 200-μm mesh filter. Dissociated cortical neurons were cultured on poly-d-lysine-coated plates at 1 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 6–7 days.

Reverse Transfection

SK-N-AS cells (3.5 × 105 cells/ml) were reverse co-transfected with human kinases (OriGene) and 2N4R tau (1 ng/well) using FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) at a 6:1 ratio (FuGENE:DNA). 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed, and AlphaScreen assays (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) were performed. GFP, CDK5/p25, and GSK3β cDNAs were also co-transfected in each experiment to serve as controls.

Cell Lysis

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS followed by incubation in lysis buffer (Invitrogen, catalog number FNN0011; 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4,100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm NaF, 20 mm Na4P2O7, 2 mm Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate with protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Applied Science), 1 mm PMSF (Sigma), Benzonase nuclease (100 units/10 ml of buffer; Novagen), and 1 mm MgCl2 (Sigma) added fresh) for 45 min on ice with gentle agitation. Plates were sealed and stored at −80 °C until further use.

AlphaScreen Assays

The AlphaScreen technology is a sandwich assay for detection of molecules of interest in serum, plasma, cell culture supernatants, or cell lysates in a sensitive, quantitative, reproducible manner. In summary, a biotinylated anti-analyte antibody binds to streptavidin-donor beads, whereas another anti-analyte antibody is conjugated to acceptor beads. In the presence of the analyte, the beads come into close proximity. The excitation of the donor beads provokes the release of singlet oxygen molecules that triggers a cascade of energy transfer in the acceptor beads, resulting in light emission.

AlphaScreen assays (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) were performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines using tau-specific antibodies. Optimized AlphaScreen assays were performed using biotinylated DA9 and acceptor bead tau antibodies (TG5, total tau; PHF1, Ser(P)-396/404; CP17, Thr(P)-231; MC6, Ser(P)-235; and CP13, Ser(P)-202). 10 μl/well optimized antibody mixture of acceptor and biotinylated DA9 was added to 384-well assay plates (Greiner) together with 5 μl/well sample or standard diluted in AlphaScreen assay buffer (0.1% casein in Dulbecco's PBS). Plates were incubated overnight in the dark at 4 °C. After overnight incubation, 5 μl/well streptavidin-coated donor beads diluted in AlphaScreen buffer was added to each well, and plates were incubated in the dark with gentle agitation at room temperature for 4 h. Plates were read (excitation, 680 nm; emission, 520–620 nm) using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

The corresponding standard curve for each phosphoepitope was used to convert the raw AlphaScreen signal into percent tau levels. -Fold change relative to GFP was calculated by dividing the percent tau level by the percent tau level of the GFP control. Transient transfection of tau would probably result in variable expression levels. Thus, the actual amount of total tau present was accounted for by dividing each -fold change value by the total tau -fold change for that well.

Statistical Analysis

Each kinase was transfected in triplicate and then assayed on 3 separate days for each epitope. The -fold change relative to total tau in each sample was calculated and ranked. Analyses were based on the assumption that most clones are inactive and should give -fold changes similar to GFP (negative control) of 1. To determine statistically significant hits from the first round of screening, the log of the -fold change relative to total tau was determined for each run. Then for each run, the “mid-inactives” were selected, the mean of these were corrected to 1, and this correction was applied to all the kinases. The mean and S.D. of the corrected log -fold change values were calculated across the three runs. “Actives” were identified if the corrected -fold change in phospho-tau epitope was >2–3 × S.D. above the corrected base line in two or more runs.

Statistically significant kinases were rescreened together with known tau kinases from the literature that were not present in the original set (46 kinases were rescreened). Following the second screen, statistically significant kinases were determined using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on log -fold change values relative to the negative control (GFP). This analysis was also applied to other results presented.

qPCR for Selection of shRNA Lentiviral Clone

hTau mouse primary neuronal cultures (DIV6 or DIV7) were infected with lentivirus containing the appropriate shRNA clones (as described above) at an m.o.i. of 1 for 4 days. 4 days postinfection, RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed. The resulting cDNA was used for qPCR using SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) and an ABI Prism PCR machine. The primers used were: GSK3a forward, 5′-AGT CCT GGT GAA CTG TCC; GSK3a reverse, 5′-GCT TGT GAG GAT GGG TTG T; GSK3b forward, 5′-GTC CGA GGA GAG CCC AAT G; GSK3b reverse, 5′-ACA ATT CAG CCA ACA CAC AGC. The relative levels of mRNA were normalized to a housekeeping gene (β-actin). Expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene and expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated cells (n = 6; ±S.E.).

Knockdown of GSK3α and GSK3β in hTau Primary Cortical Neurons

hTau mouse primary neuronal cultures (DIV6 or DIV7) were infected with lentivirus containing the optimized shRNA clones (GSK3α, GTGCTCCAGAACTCATCTTTG; GSK3β, CCGGCATGAAAGTTAGCAGAGAT) at the indicated m.o.i. values for 4 days. 4 days postinfection, cells were lysed as described above. Levels of GSK3α and GSK3β were determined by qPCR (mRNA) and Western blot (protein), and effects of knockdown of these kinases on total and phosphorylated tau levels were determined by AlphaScreen assays.

Inhibition of GSK in hTau Primary Cortical Neurons

hTau mouse primary neuronal cultures (DIV6 or DIV7) were incubated with a selective ATP-competitive GSK3 inhibitor, CT20026 (Chiron; Ref. 15), at the indicated concentration for the indicated times. After incubation, cells were washed and lysed as above. Levels of total and phosphorylated tau were measured by AlphaScreen assays.

Pathway Analysis

The kinases identified as having a significant effect on total tau levels or on tau phosphorylation in the second screen were subjected to pathway analysis using the MetaCore pathway analysis software (GeneGo). Lists of kinases were compiled according to whether they were shown to significantly increase or decrease total tau levels or tau phosphorylation. The lists were uploaded to MetaCore as experimental data sets and used to identify GeneGo pathway maps significantly enriched for these kinases. The specific interactions between each of the kinases and the tau protein were explored using the “Build Network” option to find the shortest path between objects using Dijkstra's (16) shortest path algorithm. The “Trace Pathways” option was used to investigate the connections between the kinases and the other molecules on which the kinase pathways may converge.

Domain Analysis

Structural and functional domains in the kinases that were shown to significantly increase or decrease total tau or tau phosphorylation were identified using the Pfam protein families database (17).

RESULTS

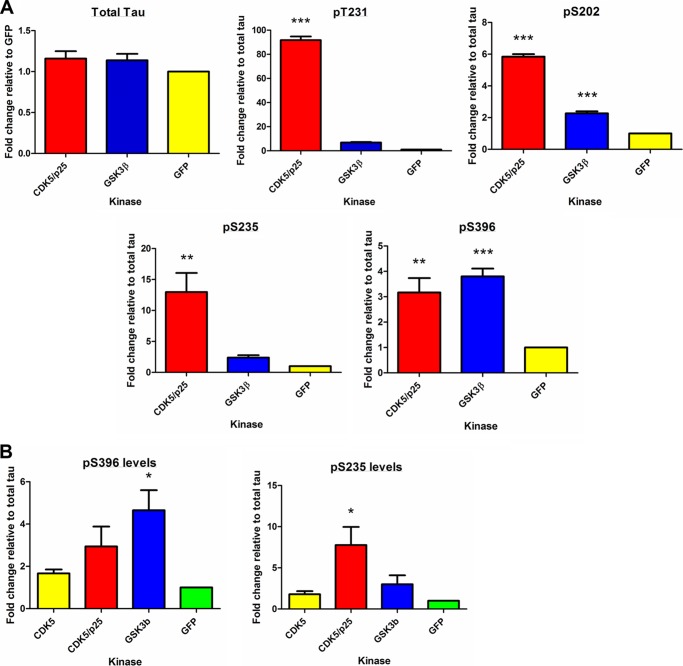

We developed a high throughput cell-based assay to identify kinases that are involved in phosphorylation of tau at AD-relevant epitopes using phosphoepitope-specific AlphaScreen assays. To assess the sensitivity and robustness of the assay before screening 352 kinases, we established the assay with two known tau kinases, CDK5 (13) and GSK3β (18), as well as GFP, the negative control. SK-N-AS human neuroblastoma cells were reverse co-transfected with known kinase or GFP and 2N4R tau in 96-well plates. 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed and assayed for total tau and phosphorylated tau using epitope-specific AlphaScreen assays. Transient transfection of tau would probably result in variable expression levels. Thus, we corrected for the amount of total tau present by dividing each -fold change value by the total tau -fold change for that well. The effect of GFP, CDK5/p25, and GSK3β on the phosphorylation of Ser(P)-202, Ser(P)-235, Ser(P)-396, and Thr(P)-231 and total tau levels is shown in Fig. 1A. GSK3β and CDK5/p25 both increased the phosphorylation levels of the tau epitopes tested relative to GFP control. CDK5/p25 was found to increase the phosphorylation levels of Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-235, and Ser(P)-202 to a much greater extent than GSK3β. Both kinases phosphorylate Ser(P)-396 to a similar degree. Overexpression of CDK5 in SK-N-AS alone without the co-transfection of p25 did not increase tau phosphorylation at CDK5 sites as shown for Ser(P)-235 or Ser(P)-396 (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of known tau kinases on tau phosphorylation. A, the effect of CDK5/p25, GSK3β, and GFP on the phosphorylation of Ser(P)-202, Ser(P)-235, Ser(P)-396, and Thr(P)-231 and total tau levels was measured using phosphoepitope-specific AlphaScreen assays. B, the effect of CDK5, CDK5/p25, GSK3β, and GFP on the phosphorylation of Ser(P)-235 and Ser(P)-396 is shown. The phospho-tau levels were normalized to total tau levels. Data shown are the average of three or four separate experiments (n = 3 per experiment). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on log -fold change values (*, **, and ***, p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 versus GFP). Error bars represent S.E.

Screen of Human Kinome

Having established the conditions for the known tau kinases, we then performed a screen of 352 human kinases available from OriGene using the known kinases and GFP as positive and negative controls, respectively. The 352 kinases were distributed in four 96-well plates, each plate containing 88 kinases. Each kinase was reverse co-transfected with human 2N4R tau into SK-N-AS neuroblastoma cells in triplicate. 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed, and AlphaScreen assays were performed on each replicate on 3 separate days for each of the epitopes. CDK5/p25 and GSK3β were used as the positive controls, GFP was used as the negative control, and screening plates were only accepted if the controls gave the expected response as shown in Fig. 1A. The repeats were averaged, and statistical analysis was performed to determine significant hits (Table 1) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” 41 kinases were identified following the first round of screening, four of which could phosphorylate all four phosphoepitopes tested (Table 2). The percentage of kinases able to phosphorylate each epitope in the initial screen were as follows: Ser(P)-202, 3.4%; Thr(P)-231, 2.8%; Ser(P)-235, 4.5%; and Ser(P)-396, 8.2%. Several known tau kinases such as GSK3β, CDK2, MAPK1, casein kinase 2, PKC, and MARK as well as a number of novel kinases such as ERN1, ADRBK2, PLK3, and ADCK5 were identified in the first round of the screen.

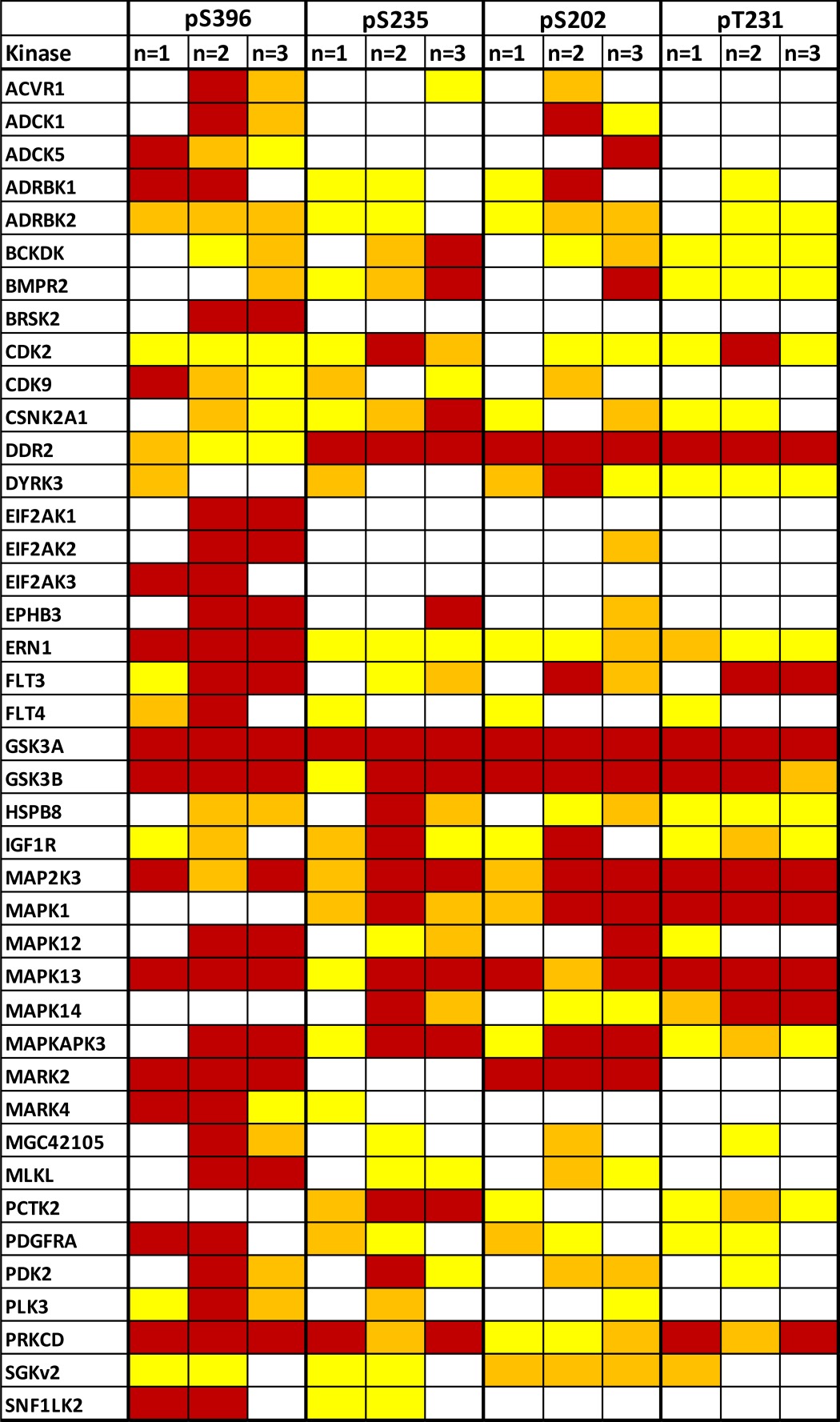

TABLE 1.

Summary of statistically significant kinases identified at each epitope after the first screen

Statistically significant kinase activity was identified if the log -fold change in phospho-tau epitope was >2 (orange) or 3 (red) × S.D. above the base line in two or more runs. Kinases were considered hits if they were red or orange in two or more runs for each epitope. White represents not statistically significant, and yellow represents 1 × S.D.; these were not considered as hits. The percentages of kinases able to phosphorylate each epitope were as follows: Ser(P)-202, 3.4%; Ser(P)-235, 4.5%; Thr(P)-231, 2.8%; and Ser(P)-396, 8.2%.

TABLE 2.

Kinases that phosphorylate more than one epitope

Kinases that phosphorylated more than one epitope in the first round of the screen are shown.

| Kinase | No. of epitopes phosphorylated | Epitopes phosphorylated |

|---|---|---|

| MAP2K3 | 4 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| GSK3α | 4 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| MAPK13 | 4 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| GSK3β | 4 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| DDR2 | 3 | Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| MAPK1 | 3 | Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| MAPKAPK3 | 3 | Ser(P)-396; Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| PRKCD | 3 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235 |

| FLT3 | 3 | Ser(P)-396; Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-202 |

| CSNK2A1 | 2 | Ser(P)-235; Ser(P)-202 |

| CDK2 | 2 | Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235 |

| MAPK14 | 2 | Thr(P)-231; Ser(P)-235 |

| MARK2 | 2 | Ser(P)-396; Ser(P)-202 |

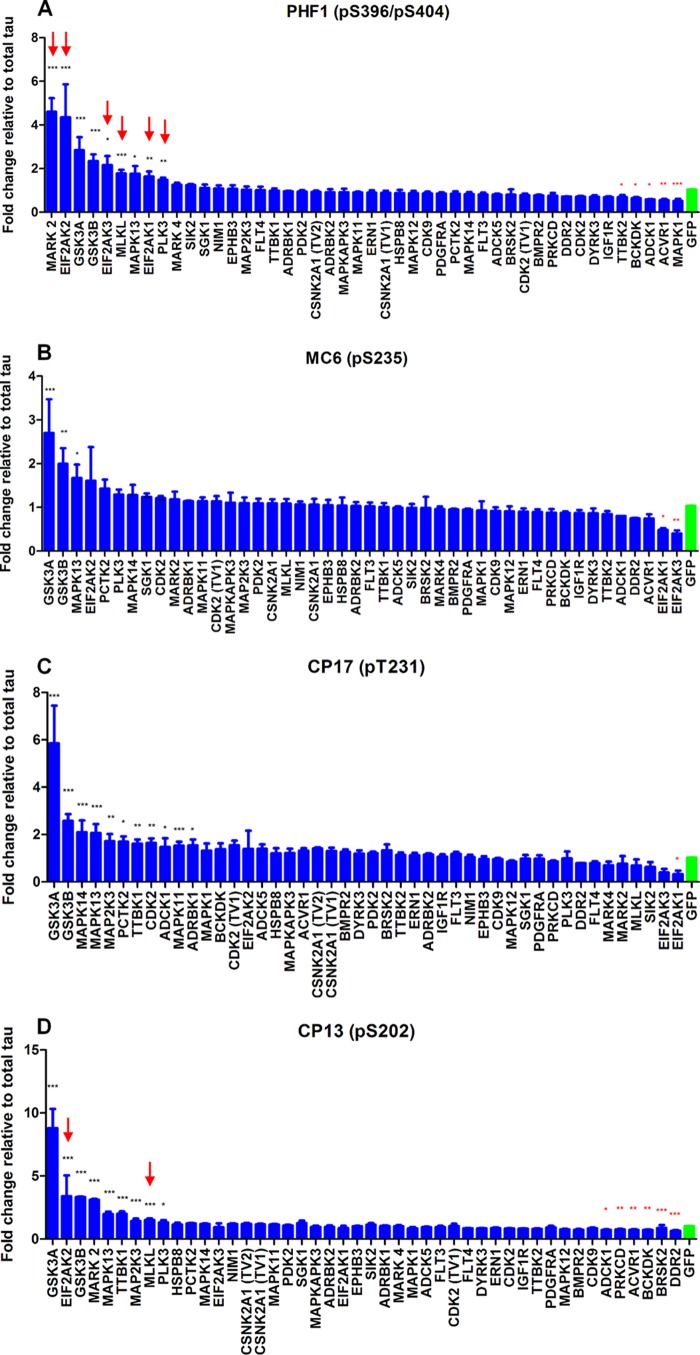

We excluded false-positive hits by repeating the screen with the hits identified from the first screen. We also included kinases from the literature that are reported to be tau kinases but were not in the original panel of kinases screened. 46 kinases (41 kinases from the first round (Table 1) together with NIM1, SIK2, MAPK11, TTBK1, and TTBK2) were screened in the second round to confirm the effects of their overexpression on total and phospho-tau epitope levels and to rank the kinases in the order of their effectiveness on tau phosphorylation. Again, CDK5/p25 and GSK3β were included as positive controls, and GFP was included as a negative control. Screens were accepted if the controls showed the expected pattern of phosphorylation as shown in Fig. 1. The effect and rank order of each of the kinases on each of the phosphoepitopes studied is shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, several kinases were found to alter total tau levels (Table 3). Six kinases significantly decreased total tau levels (eIF2AK1, eIF2AK2, eIF2AK3, MARK2, MLKL, and PLK3), and three kinases significantly increased total tau levels (ACVR1, ADCK1, and MAPK1). Nine kinases (MARK2, eIF2AK2, GSK3α, GSK3β, eIF2AK3, MLKL, MAPK13, eIF2AK1, and PLK3) significantly increased Ser(P)-396/404 levels (Fig. 2A). However, six of these (MARK2, eIF2AK2, eIF2AK3, MLKL, eIF2AK1, and PLK3) significantly reduced total tau levels and therefore may not be true hits. In addition, overexpression of TTBK2, BCKDK, ADCK1, ACVR1, and MAPK1 all significantly reduced phosphorylation of tau at Ser(P)-396. Three kinases (GSK3α, GSK3β, and MAPK13) significantly increased Ser(P)-235 levels, whereas eIF2AK1 and eIF2AK3 decreased phosphorylation at this epitope (Fig. 2B). 11 kinases (GSK3α, GSK3β, MAPK14, MAPK13, MAP2K3, PCTK2, TTBK1, CDK2, ADCK1, MAPK11, and ADRBK1) significantly increased Thr(P)-231 levels, and eIF2AK1 significantly reduced tau phosphorylation at this epitope (Fig. 2C). Finally, nine kinases (GSK3α, eIF2AK2, GSK3β, MARK2, MAPK13, TTBK1, MAP2K3, MLKL, and PLK3) significantly increased Ser(P)-202 levels; however, two of these (eIF2AK2 and MLKL) significantly reduced total tau levels and therefore may not be true hits (Fig. 2D). DDR2, BRSK2, BCKDK, ACVR1, PRKCD, and ADCK1 significantly reduced phosphorylation at this epitope.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of screening data at each epitope: Ser(P)-396 (A), Ser(P)-235 (B), Thr(P)-231 (C), and Ser(P)-202 (D). 41 kinases from the first round (shown in Table 1) together with NIM1, SIK2, MAPK11, TTBK1, and TTBK2 were rescreened. The effect of these kinases and GFP on the phosphorylation levels of Ser(P)-202, Ser(P)-235, Ser(P)-396, and Thr(P)-231 was measured using phosphoepitope-specific AlphaScreen assays. The phospho-tau levels were normalized to total tau levels. The average of three separate transfections is shown. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on log -fold change values (*, **, and ***, p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 versus GFP). Error bars represent S.E. Red arrows represent kinases that significantly reduced total tau levels.

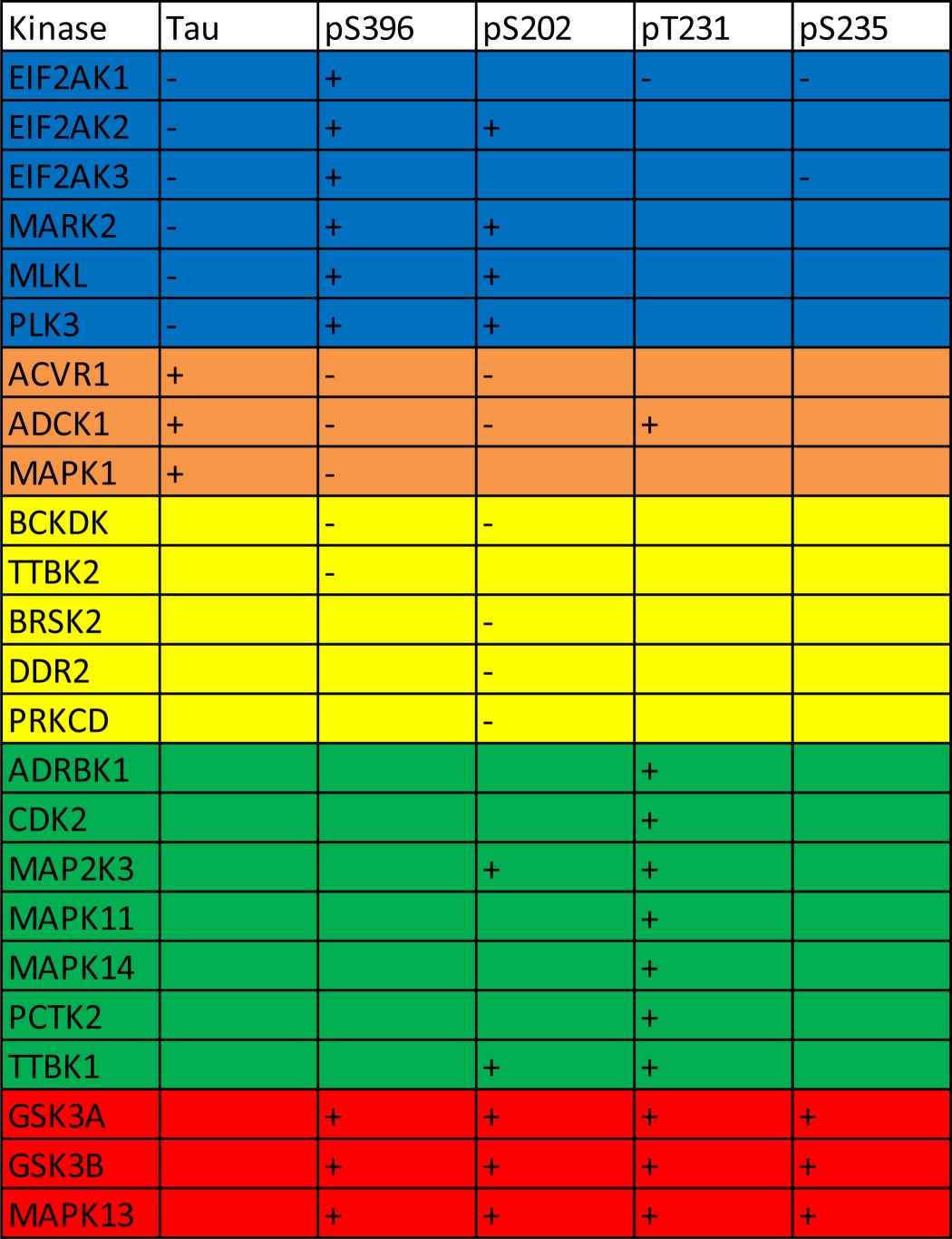

TABLE 3.

Summary of statistically significant kinases identified that either increase (+) or decrease (−) total or phospho-tau levels

41 kinases from the first round (shown in Table 1) together with NIM1, SIK2, MAPK11, TTBK1, and TTBK2 were rescreened. The kinases validated in the second round of screening are shown.

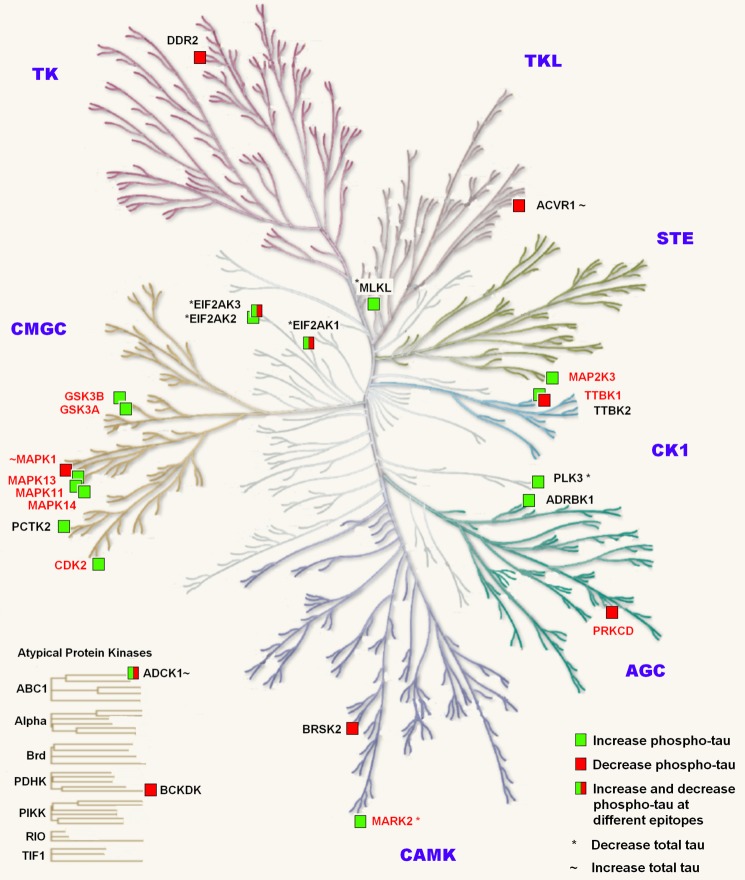

Table 3 summarizes the outcome of the second screen with respect to which kinases increased or decreased total or phosphorylated tau at each epitope. Twelve of the 24 kinases identified as hits in the second screen are known tau kinases (Fig. 3 and Refs. 5 and 6). GSK3α, GSK3β, and MAPK13 were identified as key kinases as they phosphorylated all four epitopes in both screens. The remaining 12 kinases were identified as novel kinases that modulated either tau phosphorylation or tau expression levels (Fig. 3). Of the various kinases implicated in tau phosphorylation associated with AD, considerable data support GSK3β as being a well validated target (for a review, see Ref. 2). Our data suggest that both isoforms of GSK (α and β) are able to phosphorylate tau at AD-relevant epitopes (Fig. 2). Indeed, GSK3α exhibited the greater magnitude of phosphorylation at all these sites.

FIGURE 3.

Hit kinases separated into kinase families. The diagram shows an adaptation of the phylogenetic tree where each branch represents a kinase in the human kinome as described in Manning et al. (Ref. 41; the illustration is reproduced courtesy of Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The labeled kinases are those that were associated with changes in phosphorylated tau or total tau in the kinome screen. Red text, known tau kinases; black text, novel tau kinases. *, kinases that decrease total tau levels; ∼, kinases that increase total tau levels. TK, tyrosine kinase group; TKL, tyrosine kinase-like; AGC, protein kinase A, G, and C family; CAMK, calcium- and calmodulin-regulated kinases; CK1, casein kinase 1 group; STE, constitutes three main families that sequentially activate the MAPK family; CMGC, named after the initials of some of the members of this family.

Effect of GSK3 Inhibition or Knockdown on Tau Phosphorylation

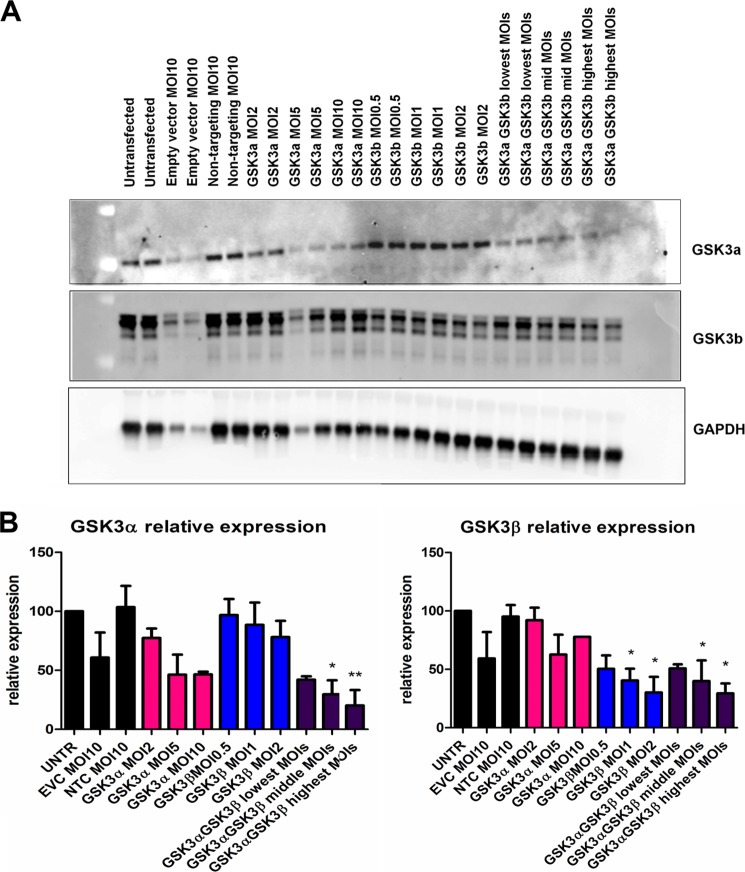

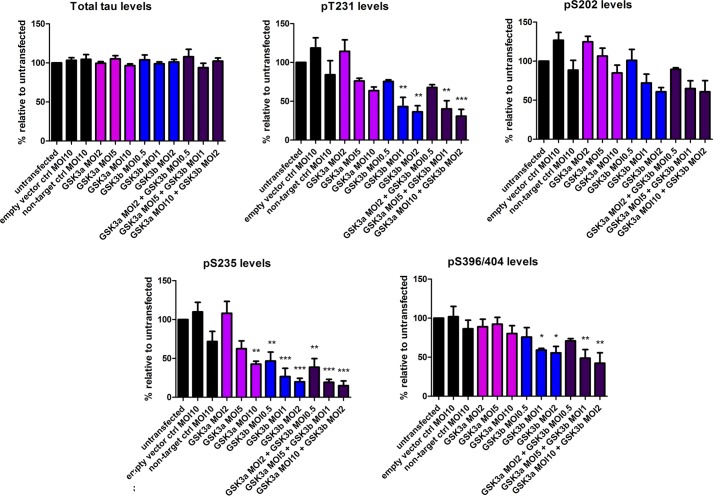

To further dissect the role of GSK3α and -β on tau phosphorylation, inhibitors of GSK3 or shRNAs to GSK3α and -β were evaluated in hTau primary cortical culture. shRNA lentiviruses (as shown under “Experimental Procedures”) to GSK3α and -β were optimized by qPCR (data not shown). The optimized shRNA lentiviruses were GTGCTCCAGAACTCATCTTTG for GSK3α and CCGGCATGAAAGTTAGCAGAGAT for GSK3β and were chosen based on their ability to selectively knock down the target genes (expression of CDK5 and Erk1/2 or the housekeeping gene (actin) were not affected; data not shown). These were used to knock down the expression of GSK3α and/or -β in hTau primary cortical neurons at the indicated m.o.i. values for 4 days. The levels of GSK3α and/or -β were evaluated by qPCR (data not shown) and Western blotting (Fig. 4). The empty vector control at an m.o.i. of 10 depressed levels of all proteins (target and non-target), suggesting that this is nonspecific. In contrast, the non-target control at an m.o.i. of 10 did not affect protein levels, and therefore the effects observed with target shRNA at an m.o.i. of 10 were perceived to be specific. Dose-dependent decreases in GSK3α or -β were obtained when the target-specific shRNA lentivirus clone was used (Fig. 4B). GSK3α shRNA lentivirus at the highest titer tested (m.o.i. of 10) achieved ∼55% knockdown of GSK3α protein level, and GSK3β shRNA lentivirus at an m.o.i. of 2 achieved ∼70% knockdown of GSK3β protein level. Increasing the virus titer resulted in nonspecific knockdown of non-target proteins (data not shown). Knockdown of both GSK3α and -β together showed a knockdown pattern similar to that observed with GSK3β knockdown alone. The effects of GSK3α and/or -β knockdown on total and phosphorylated tau levels in hTau primary cortical neurons were evaluated by AlphaScreen assays (Fig. 5). Knockdown of either GSK3α or GSK3β expression levels of 55 and 70%, respectively, had no effect on total tau levels. The highest reduction was observed in the levels of Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235. A dose-dependent reduction in Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 was achieved by knockdown of either GSK3α or GSK3β, and the effect of the double knockdown predominantly resembled that of knockdown of GSK3β alone. At the highest m.o.i., GSK3α knockdown resulted in a 40% reduction in Thr(P)-231 levels and a 60% reduction in Ser(P)-235 levels; the latter was significant. GSK3β knockdown resulted in significant reductions in Thr(P)-231(65%) and Ser(P)-235 (80%) levels. GSK3α knockdown had modest effects on Ser(P)-202 and Ser(P)-396/404 levels (∼20% reduction at the highest m.o.i.). Knockdown of GSK3β (highest m.o.i.) resulted in a 40% reduction in Ser(P)-202 levels and a 45% reduction in Ser(P)-396/404 levels. The literature suggests Ser(P)-396/404 to be a key epitope for GSK3 phosphorylation of tau (19). These genetic knockdown data seem to suggest that tau phosphorylation at Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 is greatly reduced by knockdown of GSK3 protein.

FIGURE 4.

GSK3α and -β expression levels in hTau primary cortical neurons following knockdown with shRNA. Representative Western blots (A) show levels of GSK3α and -β in duplicates following knockdown of GSK3α and/or -β with shRNA lentivirus at various m.o.i. values. Quantitative analysis of GSK3α and -β levels (B) of three independent knockdown experiments at the indicated m.o.i. values (n = 3 per experiment) is shown. EVC, empty vector control; NTC, non-targeting shRNA control; UNTR, uninfected cells. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on relative expression (* and **, p < 0.05 and 0.01). Error bars represent S.E.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of GSK3α and/or -β knockdown on total and phosphorylated tau levels in hTau primary cortical neurons. AlphaScreen assays were performed to quantitate the levels of total and phosphorylated tau (Thr(P)-231, Ser(P)-202, Ser(P)-235, and Ser(P)-396/404) in hTau primary cortical neurons following knockdown of GSK3α and/or -β with shRNA lentivirus at various m.o.i. values. The average of two separate experiments is shown (n = 3 per experiment). Reduction of GSK3α and/or -β levels had the greatest effect on Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 levels. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on phosphorylation levels (*, **, and ***, p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001). Error bars represent S.E. ctrl, control.

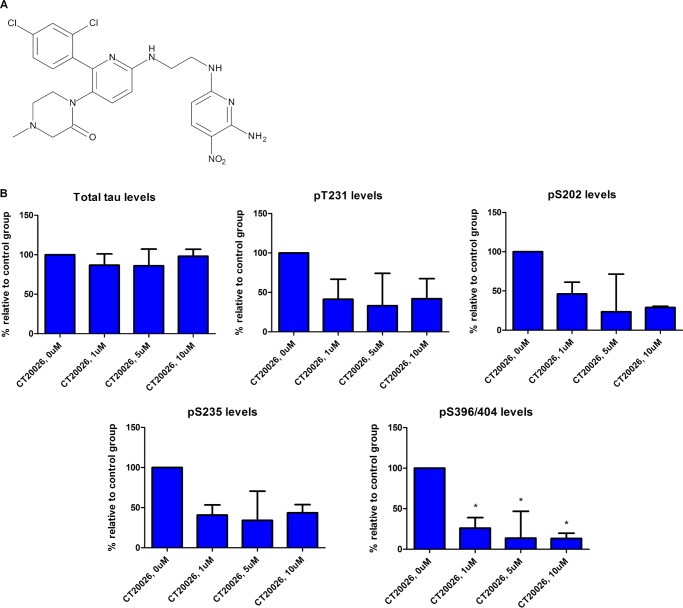

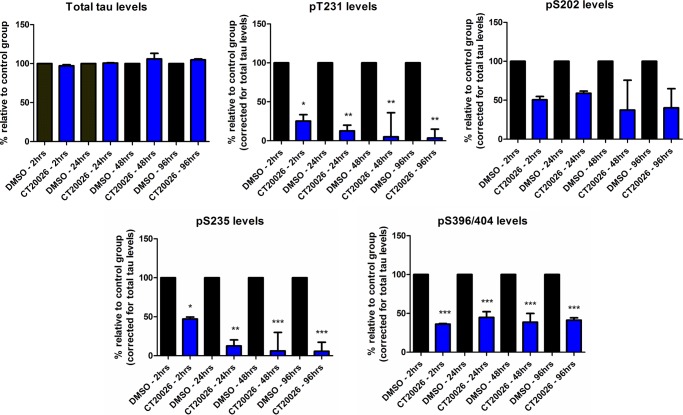

To explore the above observations further, we evaluated the effect of a selective GSK3 inhibitor, CT20026 (Fig. 6A), on total and phosphorylated tau levels in hTau primary cortical neurons. The potency of CT20026 was tested in GSK enzyme activity assays, and the compound exhibited IC50 values of 11.9 nm for GSK3β and 5.53 nm for GSK3α (data not shown). The compound was tested in a panel of 100 kinases (Invitrogen), all with IC50 values >1 μm (data not shown). Primary cortical neurons prepared from hTau mice were treated with CT20026 at the indicated concentrations for 2 h, cells were harvested, and total and phosphorylated tau levels were measured by AlphaScreen assays (Fig. 6B). Acute inhibition of GSK3 activity did not alter total tau levels but resulted in dose-dependent decreases in phosphorylated tau levels in the following rank order: Ser(P)-396/404 > Ser(P)-202 > Thr(P)-231 = Ser(P)-235. Thus, selective inhibition of GSK3 activity resulted in the greatest reduction (∼85% at 5 and 10 μm) in the levels of Ser(P)-396/404, an epitope that is known to be affected by GSK3 activity. This discrepancy between knockdown of GSK3 protein levels and inhibition of GSK3 activity could be due to incomplete knockdown of protein expression levels or to the differences in treatment paradigms. The knockdown experiments required a subchronic (4-day) treatment of cells with shRNA, whereas the inhibitor was tested acutely for 2 h. To test this further, we evaluated the effect of increased duration of GSK3 inhibition on tau phosphorylation. Primary cortical neurons prepared from hTau mice were treated with 1 μm CT20026 for 2, 24, 48, and 96 h. For the longer time points, the inhibitor was added to fresh medium daily. Cells were harvested at the appropriate time and analyzed for total and phosphorylated tau levels by AlphaScreen assays (Fig. 7). Inhibition of GSK3 activity with CT20026 did not alter total tau levels. We observed a time-dependent decrease in the levels of Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 with increased duration of GSK3 activity inhibition with CT20026. Thr(P)-231 levels were decreased by ∼75% at 2 h and greater than 90% after 96 h, whereas Ser(P)-235 levels were decreased by ∼50% at 2 h and greater than 90% after 96 h. In contrast, the levels of Ser(P)-396/404 and Ser(P)-202 were decreased ∼50–60% and remained constant despite enhanced duration of inhibition of GSK3 activity. The 96-h inhibition of GSK3 activity data suggest that Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 are greatly reduced by prolonged GSK3 inhibition and resemble the data obtained with knockdown of GSK3 expression levels.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of selective GSK3 inhibitor on tau phosphorylation levels in hTau primary cortical neurons. A, structure of the selective GSK3 inhibitor CT20026 (Chiron). B, acute inhibition of GSK3 activity (2 h) in hTau primary cortical neurons resulted in dose-dependent decreases in the following rank order: Ser(P)-396 > Ser(P)-202 > Thr(P)-231 = Ser(P)-235 (representative data shown are from two separate experiments; n = 3 per experiment). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on phosphorylation levels (*, p < 0.05). Error bars represent S.E.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of short and long term inhibition of GSK3 activity on tau phosphorylation levels. hTau primary cortical neurons were treated with 1 μm CT20026 for the indicated times. Total and phosphorylated tau levels were analyzed by AlphaScreen assays. Long term inhibition of GSK3 activity enhanced inhibition of Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 to greater than 90%, whereas Ser(P)-396/404 and Ser(P)-202 inhibition remained constant at ∼50–60% (representative data shown are from two separate experiments; n = 3 per experiment). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA test with Dunnett's multiple comparison test on phosphorylation levels (*, **, and ***, p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001). Error bars represent S.E.

Bioinformatics Analysis of Screen Data

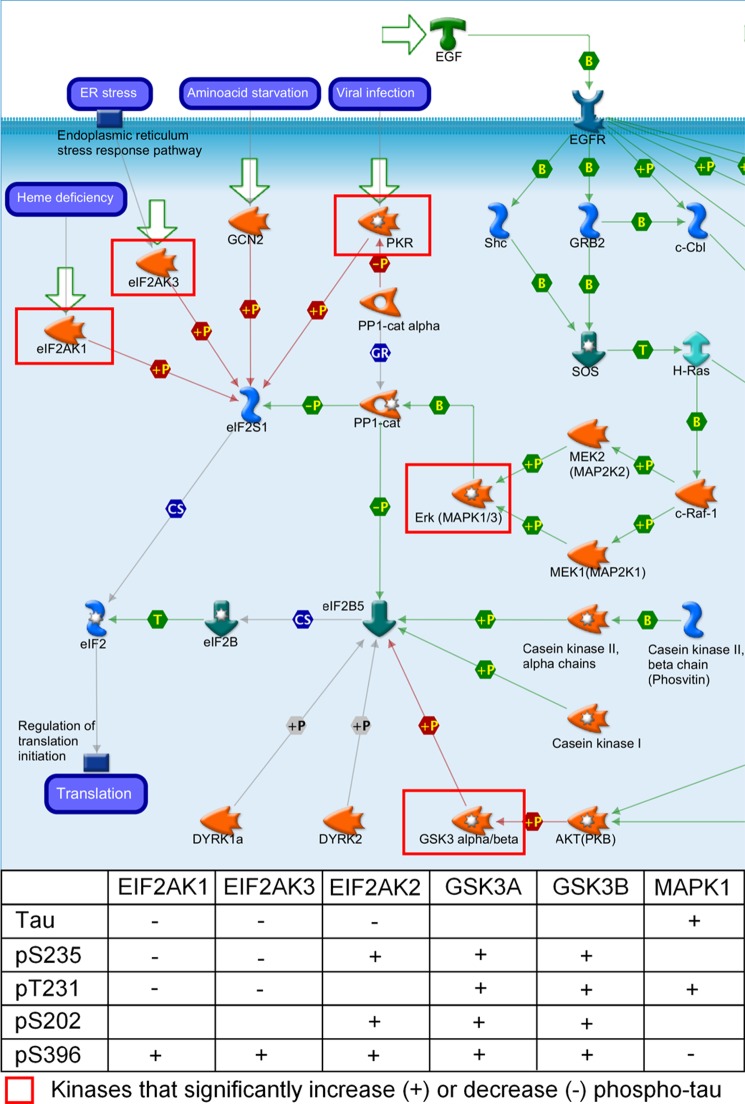

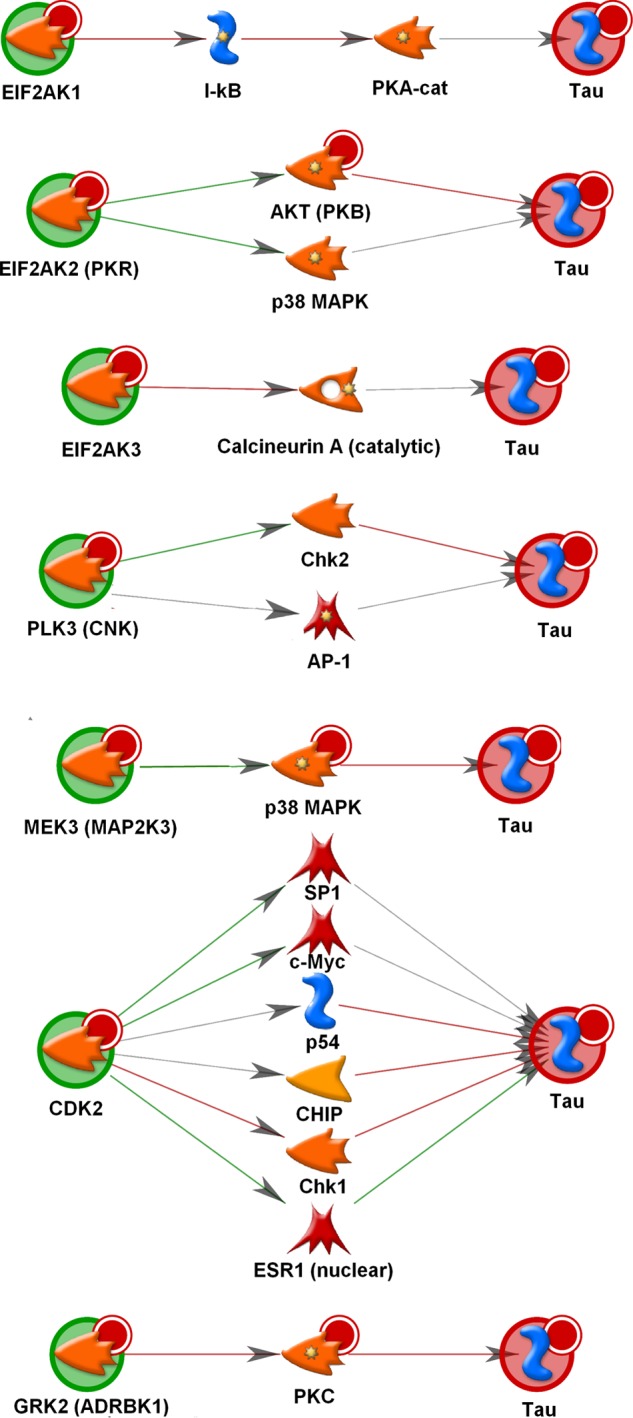

Pathway analysis using the GeneGo MetaCore pathway analysis software was performed using the kinase hits from the second screen as input. Kinases were separated into four categories: 1) kinases that increase total tau, 2) kinases that decrease total tau, 3) kinases that increase phospho-tau (with no effect on total tau), and 4) kinases that decrease phospho-tau (with no effect on total tau). GeneGo pathway maps significantly enriched for each category were identified. Nearly all of the pathways identified were focused on a single kinase or kinase group (e.g. p38) and did not reveal any particular association between the putative tau kinases in a single pathway. The exception to this is shown in Fig. 8. Several of the kinases identified from the screen are involved in the regulation of eIF2 activity GeneGo pathway map. In particular, eIF2AK1, eIF2AK2 (PKR), and eIF2AK3 all significantly decreased the total tau levels in the screen, and MAPK1 significantly increased the total tau in the screen. The pathway in Fig. 8 shows that eIF2AK1, -2, and -3 phosphorylate eIF2 subunit 1 and inhibit initiation of translation. Conversely, MAPK1 is responsible for phosphorylating the protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit, which allows protein phosphatase 1 to dephosphorylate and reactivate eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 (eIF2S1) and initiation of translation. These observations led to the hypothesis that the changes in total tau levels observed in the screen are at least in part due to inhibition or activation of initiation of translation. A number of the kinases identified to significantly increase or decrease phospho-tau have been previously annotated in the literature to phosphorylate tau directly. MetaCore was used to explore how some of the kinases identified may indirectly alter the phosphorylation state of tau. The interactions shown in Fig. 9 were identified using the Build Network, Shortest Paths option in the software. eIF2AK2 (PKR) for example was shown to increase phosphorylation of tau at epitopes Ser(P)-396/Ser(P)-404 and Ser(P)-202 but also to significantly decrease total tau levels. It was therefore postulated that this kinase may be a false positive. The interactions presented in Fig. 9 show that eIF2AK2 activates AKT (PKB) and p38 MAPK, which would in turn result in increased phosphorylation of tau, indicating that this may be a true hit after all. A similar situation is seen for PLK3 shown in Fig. 9 to activate Chk2, which in turn phosphorylates tau. Interestingly, there is also a documented interaction of PLK3 with the AP-1 transcription factor that could be responsible for the observed decrease in total tau. Both CDK2 and ADRBK1 inhibit kinases (Chk1 and PKC, respectively) that phosphorylate tau. Although these kinases were seen to increase phosphorylation of tau at Thr(P)-231, it may be that they decrease phosphorylation at other epitopes.

FIGURE 8.

GeneGo pathway map translation regulation of eIF2 activity. Part of the GeneGo pathway map for translation regulation of eIF2 activity is represented in the diagram. Molecules are represented by node icons. Different shaped node icons represent different families of proteins. Edges between nodes represent an inhibitory interaction (red), an activating interaction (green), or an unknown interaction (gray). The flow of the pathway is represented by the directionality of the arrows. The shapes in the center of the arrows describe the nature of the interaction (e.g. phosphorylation, binding, etc.). This pathway was significantly enriched for the kinases identified to significantly decrease (−) total tau (p value = 1.494e−6). The table below the pathway diagram describes whether total or phospho-tau are increased (+) or decreased (−) in the kinome screen. eIF2AK1, eIF2AK3, and eIF2AK2 (PKR) are all involved in phosphorylation of and inhibition of eIF2S1. MAPK1 as part of the ERK complex is involved in regulating the dephosphorylation of eIF2S1 via protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). GSK3α and -β are involved in phosphorylation of and inhibition of eIF2B5. EGFR, EGF receptor. SOS, son of sevenless guanine nucleotide exchange factor; CS, complex subunit; GR, group relation; B, binding; T, transformation.

FIGURE 9.

Evidence for indirect influence of kinases on tau phosphorylation. The diagrams shown represent known interactions, direct and indirect, between kinases (green circles) and tau (red circles). Molecules are represented by node icons. Different shaped node icons represent different families of proteins. Edges between nodes represent an inhibitory interaction (red), an activating interaction (green), or an unknown interaction (gray). The kinases shown (green circles) were identified as having a putative indirect effect on tau (red circles) phosphorylation by activation or inhibition of an intermediary protein. Interactions were identified using the GeneGo MetaCore pathway analysis software Shortest Paths algorithm. cat, catalytic. PKA-cat, protein kinase catalytic subunit; CNK, connector enhancer of KSR, a multidomain protein required for RAS signaling.

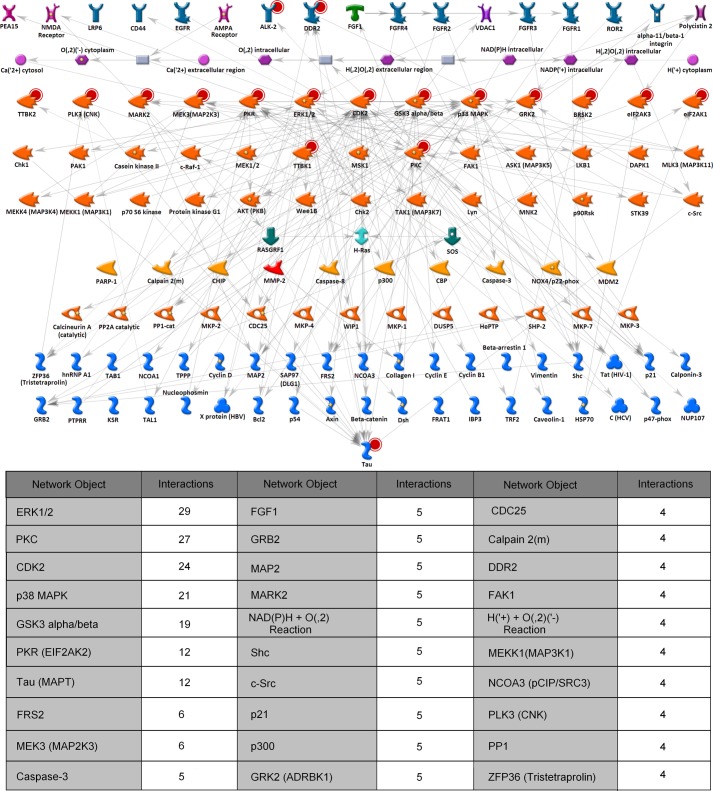

Fig. 10 shows the network generated using the Build Network, Trace Pathways option in the MetaCore software. The network building algorithm was set to search for pathways that go “from” or “through” any of the kinases identified in the screen as having an effect on phospho-tau levels and “to” the tau protein. The number of steps was set to 2 such that the molecules identified were within two interaction steps of at least one of the kinases or the tau protein. This “network fishing” approach is a method for identification of molecules up- and downstream of the experimentally determined kinases that are putatively involved in the tau phosphorylation pathways. The table below the network diagram in Fig. 10 shows the list of molecules that make >4 interactions with other molecules in the network. Although it is expected that the input kinases and tau form the most significant hubs in the network, it is interesting to see which of the kinases form the most interactions and which other molecules are highly connected in the network.

FIGURE 10.

Network fishing for molecules involved in tau phosphorylation pathways. The network shown was generated using the GeneGo MetaCore pathway analysis software to trace the putative pathways from and through the kinases identified in the kinase screen and to the tau protein. Red circles behind the icons show nodes used as input to the network building algorithm. For ease of representation, transcription factors were removed from the network, the nodes were organized by protein families, and the edges were grayed out. The table below the network shows some of the hubs in the network and the number of interactions made by each molecule. EGFR, EGF receptor; cat, catalytic; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; CBP, cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein. CNK, connector enhancer of KSR; KSR, kinase suppressor of RAS; SOS, son of sevenless guanine nucleotide exchange factor; PTPRR, protein-tyrosine phosphatase receptor type R; HePTP, hematopoietic protein-tyrosine phosphatase.

The domain composition of each of the kinases identified by the screen as having an effect on phospho-tau levels was identified from the Pfam database of protein families (data not shown). The known tau kinases GSK3β, GSK3α, MAPK1, -11, -13, -14, MAPK2K3, and CDK2 consist of a short sequence and a single kinase domain. Many of the novel tau kinases identified by this screen have more complex domain structures consisting of longer sequences and other domains as well as the kinase domain. The kinases that have a more complex domain structure include a variety of domains such as regulator of G-protein signaling, pleckstrin homology, ATPase (HATPase_c), C1, and discoidin domains.

DISCUSSION

Attenuation of tau hyperphosphorylation through inhibition of key tau kinases is an attractive therapeutic approach for the treatment of AD and other tauopathies. Identification of key and novel tau kinases would therefore be beneficial. Here, we report an unbiased approach to study the effect of 352 human kinases on their ability to phosphorylate tau at epitopes associated with AD in an attempt to identify novel kinases and generate a hypothesis regarding both direct and indirect phosphorylation of tau. We developed a high throughput reverse co-transfection cell-based assay to identify kinases that are involved in phosphorylation of tau at AD-relevant epitopes using phosphoepitope-specific AlphaScreen assays. Prior to initiating the screen, the robustness of the protocol was examined using two well characterized tau kinases, CDK5 (13) and GSK3β (18), as well as GFP, the negative control. Several cell lines were examined, including CHO cells stably overexpressing 2N4R tau (data not shown) and SK-N-AS. SK-N-AS human neuroblastoma cells were chosen for the screen as the effects of selective inhibitors and overexpression of kinases mirrored each other on the epitopes studied (data not shown), thus suggesting that SK-N-AS cells represent a robust and reproducible host cell line for the screen. In selecting a single cell line to perform the screen, false negatives were expected because specific activators are not present in the SK-N-AS cell line; e.g. CDK5 did not appear as a hit unless co-expressed with p25 (Fig. 1B). There is also the possibility of detecting false positives or false negatives due to differential expression levels of each kinase; expression levels were not confirmed by RT-PCR or Western blotting. Conversely, kinases not identified previously as tau kinases in vitro may be identified as modulators of tau phosphorylation via activation of pathways upon expression of a certain kinase; e.g. pathway analysis suggests that PLK3 (shown in Fig. 9) activates Chk2, which in turn phosphorylates tau. In addition, because 2N4R tau was overexpressed in the assay to increase the signal window, there is the possibility that an increased cytoplasmic pool of tau unbound to microtubules may result in activation of pathways that do not normally regulate tau. However, this may also mimic pathways that are activated during the disease process where a cytosolic pool of hyperphosphorylated tau has been observed in AD brain to sequester normal tau and disrupt the microtubule network (20). Our screen identified 12 known and 12 novel tau kinases; the true function of these kinases in AD and other tauopathies will have to be further evaluated in neuronal cell lines and animal models of AD and other tauopathies using genetic and pharmacological tools for each kinase. In addition, the expression levels and activation state of these kinases, particularly the novel kinases, in AD tissue relative to control patients will have to be further evaluated.

A number of candidate kinases have been proposed to phosphorylate tau; however, it is still unclear which kinases are key for disease progression. Our screen has identified three well characterized known tau kinases, GSK3α, GSK3β, and MAPK13 (SAPK4), to phosphorylate all four AD-relevant tau epitopes (Table 3), and indeed these kinases were also shown to have multiple interactions in the network fishing pathway analysis (Fig. 10). GSK3 is a proline-directed serine/threonine kinase that acts as a multifunctional downstream switch that determines the output of numerous signaling pathways. Two mammalian GSK3 isoforms encoded by distinct genes, GSK3α and GSK3β, are structurally similar and have common and non-overlapping cellular functions. There is considerable evidence in the literature that supports GSK3β being a well validated tau kinase target. Dysregulated GSK3β has been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, and reducing its activity may have therapeutic efficacy (2). Our screen data suggested that not only is GSK3β a good candidate target but that GSK3α is also a strong candidate tau kinase as GSK3α exhibited the greater magnitude of phosphorylation at all the AD-associated epitopes tested. Moreover, a recent study exploring the specific contributions of each of the GSK3α and -β isoforms in AD disease progression by using selective viral and gene silencing techniques in transgenic mouse models of AD has been described (21). Their data indicate that GSK3α contributes to both senile plaque and neurofibrillary tangle pathogenesis, whereas GSK3β only affects neurofibrillary tangle formation, thus supporting the importance of GSK3α as a therapeutic target for AD.

We therefore further dissected the roles of the two isoforms of GSK3 on tau phosphorylation in primary neuronal cultures prepared from hTau mice. In knockdown studies, the data were limited by the variable knockdown efficiencies of GSK3α and GSK3β. We were able to achieve ∼55 and 70% knockdown of protein levels of GSK3α and GSK3β, respectively; therefore, the relative contribution of GSK3α could not be validated. Under these conditions, tau phosphorylation was decreased with a rank order of Ser(P)-235 > Thr(P)-231 > Ser(P)-396/404 > Ser(P)-202. Knockdown of GSK3α only reduced phosphorylation at Ser(P)-396/404 by ∼20%, whereas GSK3β had a more robust effect, suggesting that phosphorylation of tau at these sites is predominantly mediated by GSK3β. Knockdown of GSK3β expression had a greater effect than GSK3α knockdown on tau phosphorylation levels, but this may have been due to the greater reduction in GSK3β levels achieved in the knockdown studies. Interestingly, the knockdown experiments suggested that Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235 are the epitopes that are largely reduced after reduction of GSK3 expression levels. These epitopes are normally associated with CDK5 phosphorylation of Tau (22), but CDK5, p35, and p25 protein expression levels were not affected under these knockdown conditions (data not shown). We therefore compared these knockdown data to pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 activity using a selective GSK3 inhibitor, CT20026. We observed differences in inhibition of tau phosphorylation epitopes upon acute (2-h) inhibition versus longer inhibition (24, 48, and 96 h) of GSK3 activity. Acute inhibition of GSK3 activity did not alter total tau levels but resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in tau phosphorylation levels in the following rank order: Ser(P)-396/404 > Ser(P)-202 > Thr(P)-231 = Ser(P)-235. However, prolonged inhibition of GSK3 activity resulted in decreased levels of Ser(P)-235 and Thr(P)-231 (∼90%), whereas levels of Ser(P)-396/404 and Ser(P)-202 remained constant at ∼40–45% reduction. These data are consistent with the data obtained with knockdown of GSK3 expression levels where there was a reduction in the phosphorylation of Thr(P)-231 and Ser(P)-235, the key epitopes affected. This suggests that prolonged inhibition of GSK3 activity results in modulation of other signaling pathways that may be involved in tau phosphorylation. Indeed, the network shown in Fig. 10 suggests that GSK3α/β interacts with 19 other proteins associated with tau phosphorylation. Taken together, these data have important implications when considering the clinical utility of GSK3 inhibitors for the treatment of disease. In a cellular context, prolonged kinase inhibition may result in modulation of multiple signaling pathways that could represent new points of therapeutic intervention in tau phosphorylation pathways.

Our screen also identified MAPK13 (SAPK4/p38δ) to be a key kinase in phosphorylating the four AD-relevant tau epitopes. Indeed, five of the 24 hit kinases were from the MAPK pathways, and a network fishing approach with the kinase hits identified other key molecules putatively involved in tau phosphorylation pathways, including the G-protein signaling through the Ras family of GTPases (MAPK family) pathway. In addition, four of the five MAPKs phosphorylated tau at Thr(P)-231, an epitope that is associated with early AD (9). There is also evidence in the literature that links the MAPK pathway, including the stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs), to tau phosphorylation and neurodegenerative diseases (Refs. 23 and 24; for a review, see Ref. 25). In human diseases, including AD, tau inclusions colocalize with activated MAPK family members, particularly SAPKs (26, 27). Similarly, activated SAPKs, JNK, and p38 were found to colocalize with hyperphosphorylated tau in the human P301S tau transgenic model (28). These data suggest that targeting the MAPK pathway may be of therapeutic benefit for the treatment of AD and other tauopathies. In particular, the p38 pathway is attractive as it has been linked to inflammatory diseases, and this pathway plays a key role in the activation and production of key proinflammatory cytokines. Moreover, neuroinflammation is increasingly linked to pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (29, 30); thus; inhibition of the p38 pathway may slow AD progression through anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Several of the kinases identified from the screen are involved in the activation or inhibition of initiation of translation (Fig. 8). In particular, eIF2AK1, eIF2AK2 (PKR), and eIF2AK3 all significantly decreased the total tau levels in the screen (Table 3). Interestingly, Azorsa et al. (31) recently performed a high content siRNA screen of the kinome looking at the phosphoepitope Ser(P)-262/Ser(P)-356 (12E8 epitope) on tau. They also identified eIF2AK2 as potentially affecting tau expression levels. eIF2AK1, eIF2AK2 (PKR), and eIF2AK3 indentified here are activated by different stressors and are all involved in phosphorylation and inhibition of the translation initiation factor eIF2S1. Phosphorylation of eIF2S1 results in shutdown of protein synthesis. In addition, polymorphisms within eIF2AK2 have been genetically associated with AD (32), and eIF2AK2 has been shown to be activated in AD brain (33). Reductions in tau levels have also been shown to prevent amyloid β from causing neuronal deficits in cell culture and in transgenic mice expressing human amyloid precursor protein (34). The authors also suggest that in mice a 50% reduction of endogenous tau is well tolerated, increases resistance to chemically induced seizures, and markedly reduces amyloid β and ApoE4 fragment-induced neuronal and cognitive impairments in vivo (34). These data suggest that reducing overall tau levels may be of therapeutic value, and down-regulation of the eIF2 pathway may be one approach to reducing tau levels.

The variety of domain structures, particularly for the novel kinases identified in this study (data not shown), demonstrates the complex functionality of these kinases. It is possible that the cell-based approach to the screen has enabled the identification of these kinases because they are not acting in isolation but in the context of the cell require the other factors available to function. It is also noteworthy that eIF2AK3, BRSK2, ACVR1, and DDR2 are transmembrane proteins and that ADRBK1 (GRK2) and PKC (PRCKD in this case) are membrane-associated proteins. There is some evidence that the phosphorylation state of tau directly impacts its localization and that tau is trafficked between the cytosol and the neuronal membrane depending on the phosphorylation state (35). BCKDK is localized to the mitochondria, and although very little is known about ADCK1, the ABC1 protein in yeast (from which the ABC1 domain was identified) is imported into the mitochondria. It has been suggested that hyperphosphorylation of tau may contribute to axonal degeneration by disrupting mitochondrial transport in AD (36).

The network shown in Fig. 10 identifies many molecules other than kinases that are likely to be affected or involved in the pathways around tau phosphorylation. For example, it has been demonstrated that tau can bind to the N-terminal SH3 domain of Grb2. Hyperphosphorylated tau from AD brain did not bind SH3 domain proteins, but the binding was restored by phosphatase treatment (37). It may be that signaling through these molecules is disrupted in AD by hyperphosphorylation. Histone acetyltransferase p300 also makes five interactions in the network. Min et al. (38) recently showed that p300 is involved in tau acetylation and that inhibiting p300 promoted deacetylation of tau and eliminated tau phosphorylation associated with tauopathy in primary neurons. Calpain 2 was also identified by the network fishing approach as having a role to play in tau phosphorylation pathways. It has recently been shown that genetic deficiency of calpastatin, a calpain-specific inhibitor protein, augments tau phosphorylation and the amyloid β-triggered pathological cascade and increases mortality in transgenic mice expressing amyloid precursor protein (39). These molecules and some of the others identified by the protein interaction network approach may represent new points of therapeutic intervention in tau phosphorylation pathways.

A therapeutic strategy for AD and other tauopathies based on inhibition of tau phosphorylation is appealing. However, kinases are a difficult class of drug targets as they modulate multiple biological pathways, and therefore, designing selective molecules that avoid on-target toxicity is a challenge. An alternative approach would be to investigate non-selective kinase inhibitors as reducing the overall level of tau phosphorylation may be beneficial. In this respect, a moderate reduction in multiple kinase activities might lead to a reduction in the on- and off-target side effects that are observed when a specific kinase is completely suppressed. Indeed, Le Corre et al. (40) used an analog of K252a (SRN-003-556), a molecule that inhibits GSK3, Erk2, CDK1, PKA, and protein kinase C with equal efficacies, on JNPL3 tau transgenic mice and showed decreased hyperphosphorylated tau and improved motor impairments.

The data from this screen together with the pathway analysis have identified novel tau kinases and pathways that may be involved in generating phosphorylation of tau associated with pathological forms of the protein observed in AD and other tauopathies. The exact role of these kinases in tau phosphorylation will need to be evaluated in further studies.

Footnotes

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- DIV

- days in vitro

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- GSK

- glycogen synthase kinase

- hTau

- human tau

- MARK

- microtubule affinity-regulating kinase

- MLKL

- mixed lineage kinase domain-like

- BCKDK

- branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase

- PRKCD

- protein kinase Cδ.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hutton M., Lendon C. L., Rizzu P., Baker M., Froelich S., Houlden H., Pickering-Brown S., Chakraverty S., Isaacs A., Grover A., Hackett J., Adamson J., Lincoln S., Dickson D., Davies P., Petersen R. C., Stevens M., de Graaff E., Wauters E., van Baren J., Hillebrand M., Joosse M., Kwon J. M., Nowotny P., Che L. K., Norton J., Morris J. C., Reed L. A., Trojanowski J., Basun H., Lannfelt L., Neystat M., Fahn S., Dark F., Tannenberg T., Dodd P. R., Hayward N., Kwok J. B., Schofield P. R., Andreadis A., Snowden J., Craufurd D., Neary D., Owen F., Oostra B. A., Hardy J., Goate A., van Swieten J., Mann D., Lynch T., Heutink P. (1998) Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393, 702–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee V. M., Brunden K. R., Hutton M., Trojanowski J. Q. (2011) Developing therapeutic approaches to tau, selected kinases, and related neuronal protein targets. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1, a006437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gómez-Isla T., Hollister R., West H., Mui S., Growdon J. H., Petersen R. C., Parisi J. E., Hyman B. T. (1997) Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 41, 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trinczek B., Biernat J., Baumann K., Mandelkow E. M., Mandelkow E. (1995) Domains of tau protein differential phosphorylation, and dynamic instability of microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1887–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sergeant N., Bretteville A., Hamdane M., Caillet-Boudin M. L., Grognet P., Bombois S., Blum D., Delacourte A., Pasquier F., Vanmechelen E., Schraen-Maschke S., Buée L. (2008) Biochemistry of Tau in Alzheimer's disease and related neurological disorders. Expert Rev. Proteomics 5, 207–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanger D. P., Seereeram A., Noble W. (2009) Mediators of tau phosphorylation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 1647–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higuchi M., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q. (2002) Tau and axonopathy in neurodegenerative disorders. Neuromolecular Med. 2, 131–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eidenmüller J., Fath T., Hellwig A., Reed J., Sontag E., Brandt R. (2000) Structural and functional implications of Tau hyperphosphorylation: information from phosphorylation-mimicking mutated tau proteins. Biochemistry 39, 13166–13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Augustinack J. C., Schneider A., Mandelkow E.-M., Hyman B. T. (2002) Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 103, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kimura T., Ono T., Takamatsu J., Yamamoto H., Ikegami K., Kondo A., Hasegawa M., Ihara Y., Miyamoto E., Miyakawa T. (1996) Sequential changes of tau-site-specific phosphorylation during development of paired helical filaments. Dementia 7, 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schneider A., Biernat J., von Bergen M., Mandelkow E., Mandelkow E. M. (1999) Phosphorylation that detaches tau protein from microtubules (Ser 262, Ser 214) also protects it against aggregation into Alzheimer's paired helical filaments. Biochemistry 38, 3549–3558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cho J. H., Johnson G. V. (2003) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β phosphorylates at both primed and unprimed sites. Differential impact on microtubule binding. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wen Y., Planel E., Herman M., Figueroa H. Y., Wang L., Liu L., Lau L.-F., Yu W. H., Duff K. E. (2008) Interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3β mediated by neuregulin signaling leads to differential effects on tau phosphorylation and amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Neurosci. 28, 2624–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andorfer C., Kress Y., Espinoza M., de Silva R., Tucker K. L., Barde Y. A., Duff K., Davies P. (2003) Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J. Neurochem. 86, 582–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nuss J. M., Harrison S. D., Ring D. B., Boyce R. S., Johnson K., Pfister K. B., Ramurthy S., Seely L., Wagman A. S., Desai M., Levine B. H. (October, 24 2002) U. S. Patent 20,020,156,087

- 16. Dijkstra E. W. (1959) A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numerische Mathematik 1, 269–271 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., Pang N., Forslund K., Ceric G., Clements J., Heger A., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A., Finn R. D. (2012) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maas T., Eidenmüller J., Brandt R. (2000) Interaction of tau with the neural membrane cortex is regulated by phosphorylation at sites that are modified in paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15733–15740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernández F., Lucas J. J., Cuadros R., Avila J. (2003) GSK-3 dependent phosphoepitopes recognized by PHF-1 and AT-8 antibodies are present in different tau isoforms. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 1087–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alonso A. C., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K. (1996) Alzheimer's disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nat. Med. 2, 783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hurtado D. E., Molina-Porcel L., Carroll J. C., Macdonald C., Aboagye A. K., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M. (2012) Selectively silencing GSK-3 isoforms reduces plaques and tangles in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 7392–7402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H., Noble W. (2009b) Tau phosphorylation; the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goedert M., Hasegawa M., Jakes R., Lawler S., Cuenda A., Cohen P. (1997) Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by stress-activated protein kinases. FEBS Lett. 409, 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buée-Scherrer V., Goedert M. (2002) Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by stress-activated protein kinases in intact cells. FEBS Lett. 515, 151–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harper S. J., Wilkie N. (2003) MAPKs: new targets for neurodegeneration. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 7, 187–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferrer I., Blanco R., Carmona M., Puig B. (2001) Phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK-P), protein kinase of 38 kDa (p38-P), stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK/JNK-P), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaM kinase II) are differentially expressed in tau deposits in neurons and glial cells in tauopathies. J. Neural. Transm. 108, 1397–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atzori C., Ghetti B., Piva R., Srinivasan A. N., Zolo P., Delisle M. B., Mirra S. S., Migheli A. (2001) Activation of the JNK/p38 pathway occurs in diseases characterized by tau protein pathology and is related to tau phosphorylation but not to apoptosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60, 1190–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allen B., Ingram E., Takao M., Smith M. J., Jakes R., Virdee K., Yoshida H., Holzer M., Craxton M., Emson P. C., Atzori C., Migheli A., Crowther R. A., Ghetti B., Spillantini M. G., Goedert M. (2002) Abundant tau filaments and nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P301S tau protein. J. Neurosci. 22, 9340–9351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnson G. V., Bailey C. D. (2003) The p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway in Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Neurol. 183, 263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee Y.-J., Han S. B., Nam S.-Y., Oh K.-W., Hong J. T. (2010) Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Arch. Pharm. Res. 33, 1539–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Azorsa D. O., Robeson R. H., Frost D., Meec hoovet B., Brautigam G. R., Dickey C., Beaudry C., Basu G. D., Holz D. R., Hernandez J. A., Bisanz K. M., Gwinn L., Grover A., Rogers J., Reiman E. M., Hutton M., Stephan D. A., Mousses S., Dunckley T. (2010) High-content siRNA screening of the kinome identifies kinases involved in Alzheimer's disease-related tau hyperphosphorylation. BMC Genomics 11, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bullido M. J., Martínez-García A., Tenorio R., Sastre I., Muñoz D. G., Frank A., Valdivieso F. (2008) Double stranded RNA activated EIF2α kinase (EIF2AK2; PKR) is associated with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 1160–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang R. C., Wong A. K., Ng H. K., Hugon J. (2002) Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) is associated with neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport 13, 2429–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morris M., Maeda S., Vossel K., Mucke L. (2011) The many faces of tau. Neuron 70, 410–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pooler A. M., Usardi A., Evans C. J., Philpott K. L., Noble W., Hanger D. P. (2012) Dynamic association of tau with neuronal membranes is regulated by phosphorylation. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 431.e27–431.e38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shahpasand K., Uemura I., Saito T., Asano T., Hata K., Shibata K., Toyoshima Y., Hasegawa M., Hisanaga S. (2012) Regulation of mitochondrial transport and inter-microtubule spacing by tau phosphorylation at the sites hyperphosphorylated in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 2430–2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reynolds C. H., Garwood C. J., Wray S., Price C., Kellie S., Perera T., Zvelebil M., Yang A., Sheppard P. W., Varndell I. M., Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H. (2008) Phosphorylation regulates tau interactions with Src homology 3 domains of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cgamma1, Grb2, and Src family kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18177–18186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Min S. W., Cho S. H., Zhou Y., Schroeder S., Haroutunian V., Seeley W. W., Huang E. J., Shen Y., Masliah E., Mukherjee C., Meyers D., Cole P. A., Ott M., Gan L. (2010) Acetylation of tau inhibits its degradation and contributes to tauopathy. Neuron 67, 953–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Higuchi M., Iwata N., Matsuba Y., Takano J., Suemoto T., Maeda J., Ji B., Ono M., Staufenbiel M., Suhara T., Saido T. C. (2012) Mechanistic involvement of the calpain-calpastatin system in Alzheimer neuropathology. FASEB J. 26, 1204–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Le Corre S., Klafki H. W., Plesnila N., Hübinger G., Obermeier A., Sahagún H., Monse B., Seneci P., Lewis J., Eriksen J., Zehr C., Yue M., McGowan E., Dickson D. W., Hutton M., Roder H. M. (2006) An inhibitor of tau hyperphosphorylation prevents severe motor impairments in tau transgenic mice. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 103, 9673–9678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Manning G., Whyte D. B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S. (2002) The protein kinase complement of the human kinome. Science 298, 1912–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]