Abstract

Background

Fetal alcohol-related growth restriction persists through infancy but its impact later in life is less clear. Animal studies have demonstrated important roles for maternal nutrition in FASD, but the impact of prenatal maternal body composition has not been studied in humans. This study examined the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on longitudinal growth from birth through young adulthood and the degree to which maternal weight and body mass index (BMI) moderate these effects.

Methods

480 mothers were recruited at their first prenatal clinic visit to over-represent moderate-to-heavy use of alcohol during pregnancy, including a 5% random sample of low-level drinkers and abstainers. They were interviewed at every prenatal visit about their alcohol consumption using a timeline follow-back approach. Their children were examined for weight, length/height, and head circumference at birth, 6.5 and 13 months, and 7.5, 14, and 19 years.

Results

In multiple regression models with repeated measures (adjusted for confounders), prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with longitudinal reductions in weight, height, and weight-for-length/BMI that were largely determined at birth. At low-to-moderate levels of exposure, these effects were more severe in infancy than in later childhood. By contrast, effects persisted among children whose mothers drank at least monthly and among those born to women with alcohol abuse and/or dependence who had consumed ≥4 drinks/occasion. In addition, effects on weight, height, and head circumference were markedly stronger among children born to mothers with lower prepregnancy weight.

Conclusions

These findings confirm prior studies demonstrating alcohol-related reductions in weight, height, weight-for-height/BMI, and head circumference that persist through young adulthood. Stronger effects were seen among children born to mothers with smaller prepregnancy weight, which may have been due to attainment of higher blood alcohol concentrations in smaller mothers for a given amount of alcohol intake or to increased vulnerability in infants born to women with poorer nutrition.

Keywords: fetal alcohol syndrome, prenatal alcohol exposure, intrauterine growth retardation, postnatal growth, body composition, prepregnancy weight, maternal nutrition

Introduction

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) include a range of teratogenic effects of prenatal alcohol exposure, including cognitive and neurologic deficits and growth restriction. Growth retardation is required for a diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), the most severe of the FASD, and is a contributing factor in the diagnosis of partial FAS (PFAS). Four decades of animal and human studies have demonstrated intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) among offspring exposed prenatally to alcohol, with smaller weight, length, and head circumference at birth (Streissguth et al., 1981, Greene et al., 1991, Jacobson et al., 1994). These prenatal growth deficits have been shown to persist through infancy in several human cohorts (Streissguth et al., 1981, Day et al., 1992, Jacobson et al., 1994, Carter et al., 2007). In a prospective cohort of moderately exposed infants in Detroit, prenatal alcohol exposure was related to both fetal growth restriction and a postnatal reduction in weight at 6.5 months that was independent of birth weight (Jacobson et al., 1994). This study was among the first to demonstrate alcohol-related fetal growth restriction in non-syndromal children (Day et al., 1990, Coles et al., 1991, Sampson et al., 1994). Alcohol-related fetal growth restriction and a subsequent postnatal weight reduction were also seen in a prospective cohort in Cape Town, South Africa, but the postnatal weight reduction appeared to resolve between ages 13 months and 5 years(Carter et al., In press).

Although alcohol-related prenatal growth deficits have consistently been shown to persist through infancy, the natural history of alcohol-related growth restriction in later childhood is less clear. In a prospective study of alcohol-exposed children in a low-income, low-to-moderately exposed Pittsburgh cohort, alcohol-related deficits in height, weight, head circumference, and skinfold thickness persisted through 14 years (Day et al., 2002). Similar effects were seen through 8 years in a study of impoverished children prenatally exposed to alcohol and cocaine in Boston (Lumeng et al., 2007). In our heavily-exposed longitudinal cohort in Cape Town (Jacobson et al., 2008b, Carter et al., In press), fetal alcohol-related growth reductions persisted through 9 years. By contrast, long-term deficits in childhood anthropometrics were not seen in the Seattle 500 cohort study of predominantly Caucasian children exposed at moderate levels in more optimal socioeconomic circumstances (Streissguth et al., 1981, 1991, Sampson et al., 1994, O’Callaghan et al., 2003). The amelioration of the growth deficits in that cohort may have been due to ethnic/racial background characteristics and/or postnatal environmental influences that may have mitigated alcohol-related growth restriction.

It has been widely postulated that the nutritional status of a woman who drinks alcohol during pregnancy may affect the severity of fetal alcohol impairment. In case-control studies examining risk factors for FAS in South Africa, weight, height, head circumference, and body mass index (BMI) were smaller for mothers of children with FAS and PFAS than for mothers of children without these diagnoses in the same community (May et al., 2008, May and Gossage, 2011). Alcoholics commonly choose alcohol over more nutrient-dense foods and are prone to hypoglycemia and micronutrient deficiencies (Manari et al., 2003). Differences in body composition and energy intake around the time of drinking are also known to affect blood alcohol levels for a given amount of consumption (Lands, 1998). Furthermore, insufficient maternal energy intake, prepregnancy weight, and gestational weight gain are each risk factors for IUGR, regardless of alcohol consumption (Neggers et al., 1995). In one of the first studies examining the impact of maternal diet on alcohol effects, Weinberg et al. (1990) found more severe ethanol-related skeletal ossification deficits in rat pups whose mothers were fed a protein-deficient diet. Another study found changes in expression of genes related to stress and external stimulus responses, transcriptional regulation, cellular homeostasis, and protein metabolism among pregnant, ethanol-exposed rats fed 70% of a normal diet (Shankar et al., 2006) that were not present in rats exposed only to alcohol or the reduced diet. Recent studies have also demonstrated protective effects of micronutrients, including choline (Tran and Thomas, 2007, Thomas et al., 2009), folic acid (Xu et al., 2008), and zinc (Keen et al., 2010). In humans, the potential roles of nutrition in moderating effects of prenatal alcohol exposure remain largely unknown.

The Detroit prospective cohort described above has been followed longitudinally from birth through age 19 years. The aims of the current study were: (1) to examine the relation between prenatal alcohol exposure and longitudinal postnatal growth through 19 years postpartum; (2) to assess whether effects of alcohol on growth are dose-dependent or are most evident above certain thresholds of exposure; 3) to examine whether the effects of alcohol on growth change over the course of development through age 19 years; and (4) to examine the impact of maternal nutritional status, as indicated by prepregnancy weight and BMI and/or weight gain during pregnancy on fetal alcohol-related growth restriction.

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 480 children whose mothers had been recruited for a longitudinal study on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on development (Jacobson et al., 2002, 2004). All African American women presenting for their initial visit to the prenatal clinic of a large urban maternity hospital were interviewed regarding alcohol consumption both currently and at conception. Women who reported alcohol consumption at conception of at least 0.5 oz absolute alcohol (AA), the equivalent of 1 standard drink/day, and a random sample of 5% of the light drinkers and abstainers were invited to participate. To reduce the risk that prenatal alcohol and cocaine effects might not be separable statistically, an additional 78 women with both high cocaine (≥ 2 days/week) and low alcohol use (<0.5 AA/day) were also included in the cohort. Infants were excluded for birth weight <1500 g, gestational age (GA) at delivery <32 weeks, major chromosomal anomalies or neural tube defects, or multiple gestation pregnancy.

Children were assessed at 6.5 and 13 months postpartum and at 7.5, 14, and 19 years. For 62 pre-term infants (32.0–38.0 weeks gestation), infancy assessments were conducted at the post-conceptual age equivalent to that of full-term infants. Informed consent was obtained from the mother at recruitment and at each visit. Children gave oral assent at 7.5 and 14 years and written consent at 19 years. Approval for human research was obtained from the Wayne State University Human Investigation Committee.

Maternal alcohol, smoking, and drug use

The mother was interviewed at each prenatal clinic visit (mean = 5.3 visits) regarding her drinking during the previous 2 weeks using a timeline follow-back interview (Jacobson et al., 2002). Volume consumed was recorded for each type of alcohol beverage and converted to oz of absolute alcohol (AA) using weights proposed by Bowman et al. (liquor—0.4, beer—0.04, wine—0.2) (1975). Three summary measures were constructed—oz AA/day averaged across pregnancy, oz AA/drinking day (quantity/occasion), and frequency of drinking (number of days/week or month). At the first clinic visit, the mother was also asked to recall her day-by-day drinking during a typical week around the time she became pregnant. Due to wide variability in the dosage and degree of purity of illicit drugs, data were summarized in terms of the average number of days/month for cocaine, opiates (e.g., heroin, methadone, codeine), and marijuana. Details regarding assessment of illicit drug use are provided in Jacobson et al. (1993).

Control variables

Data were obtained on demographic background variables, including maternal age at delivery, number of prior pregnancies, years of education, and marital status. For most infants, gestational age (GA) was measured using a Ballard assessment at 30–48 hours postpartum by a research-trained nurse specialist (Ballard et al., 1979). Where the Ballard differed from the best obstetrical estimate by >2 weeks, a second Ballard was performed, and the infant was assigned the median of the three GA measures. Information was also obtained regarding whether the infant was breastfed and, if so, for how long (Jacobson et al., 1991). Mothers were asked what their weight had been just prior to becoming pregnant. Weight gain during pregnancy was calculated by subtracting prepregnancy weight from maternal weight recorded in the mother’s delivery record. Maternal standing height was obtained at a postnatal visit, and prepregnancy BMI (weight(kg) /height(m)2) was calculated based on self-reported prepregnancy weight (CDC, 2007). The Hollingshead (1975) Scale for Socioeconomic Status was assessed at 6.5 months and 7.5 and 14 years. Stressful life events were assessed in separate maternal and child interviews at 7.5 and 14 years (Holmes and Rahe, 1967, Yumoto et al., 2008).

Pre- and postnatal child growth

All measurements were obtained by examiners blind with respect to prenatal alcohol, smoking, and drug exposures. Birth weight was obtained from hospital medical records. Crown-heel length and head circumference were measured at 30–48 hours postpartum by a trained research assistant. Weight, length (during infancy) or height, and head circumference were measured by a trained research assistant at each postnatal visit. Using 2000 CDC norms, Z-scores were calculated for weight-for-age (WAZ), length- or height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-length (WLZ) for infancy visits, and BMI (BMIZ) at 7.5, 14, and 19 years (Kuczmarski et al., 2000, Kuczmarski et al., 2002). The variables relating weight to length/height—WLZ at 6.5 and 13 months and BMIZ at 7.5, 14, and 19 years—were examined as a single longitudinal outcome. Given the lack of standard, continuous percentiles for head circumference after age 3 years, raw values (cm) were used for all ages in longitudinal analyses.

Statistical analyses

All variables were checked for normality of distribution. AA/day, AA/drinking day, opiate, cocaine, and marijuana use and weeks of breastfeeding were all positively skewed (skew > 3.0) and were normalized by means of log(X + 1) transformation. Seven outliers on maternal smoking were transformed by recoding to one point greater than the highest observed value (Winer, 1971). Any control variable that was related to a given outcome variable at p < .20 in univariate analyses was considered a potential confounder (Maldonado and Greenland, 1993). Covariates were considered for inclusion in the final multivariate models based on a forward selection approach, in which each potential confounder was added sequentially to the analysis in order of the magnitude of its relation to the outcome variable. Covariates were retained in the model only if they resulted in a change of at least 10% in the magnitude of the regression coefficient relating alcohol exposure to the outcome variable at step of entry (Greenland and Rothman, 1998, Jacobson et al., 2008a).

Repeated measures multiple regression analyses (proc mixed; SAS v. 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) were used to examine the relation of alcohol exposure (oz AA/day across pregnancy, oz AA/occasion across pregnancy, and frequency of maternal drinking) to each of the longitudinal growth outcomes (WAZ, HAZ, WLZ or BMIZ, and head circumference). This method adjusts for within-subject variability and allows for pairwise deletion, so that in cases with a missing outcome observation (e.g., missed visit), the child’s observations from all attended visits are included. To assess whether the relation between prenatal alcohol exposure and growth was dose-dependent and/or dependent on exposure attaining a minimum threshold, children were grouped into five alcohol exposure levels (0, 0.01–0.49, 0.5–1.0, 1.0–1.99, ≥ 2 oz AA/day) and ANOVAs were used to compare growth outcomes between groups. Groups based on average number of days/month on which mothers drank during pregnancy (0; 0.01–0.99, 1–3.99, ≥ 4) were also compared.

To assess potential interaction effects of child age on the relation between prenatal alcohol exposure and growth (i.e., whether the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth changed over time), interaction terms were constructed (alcohol exposure X age at time of measurement) and included in regression analyses for each growth outcome adjusted for confounders. To examine the patterns of these interaction effects over time, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were then used to compare between-group means for each growth outcome at each age-point (adjusting for the confounders included in the interaction regression models). To examine rates of growth across the age intervals, change in Z-scores for weight, length or height, and weight-for-length (or BMI) and change in head circumference (cm) was calculated for each child for each interval (e.g., birth to 6.5 months, 6.5 to 12 months, 12 months to 5 years, etc.). ANCOVAs were then used to compare changes in anthropometric measures across each age interval between prenatal alcohol exposure groups. To assess potential interaction effects of maternal prepregnancy weight, prepregnancy BMI, and weight gain during pregnancy on the relation between prenatal alcohol exposure and growth, interaction terms were constructed (alcohol exposure X maternal anthropometric indicator), and each was included in separate regression analyses adjusting for confounders selected as described above. In models where the regression coefficients for the interaction terms were significant at p < .10, the cohort was split into two groups at the median for the maternal anthropometric indicator, and separate regression models (adjusting for confounders) were performed for each group.

Results

Maternal characteristics, alcohol consumption, and drug use

At recruitment, 58.1% of the women were high school graduates (Table 1). Socioeconomic status improved over time. During infancy, 60.7% of the primary caregiver’s reports placed them in the lowest category average on the Hollingshead (1975) (Level V: “unskilled workers”), compared with only 17.1% by the 14-year visit. 28.0% of the mothers’ prepregnancy BMIs signified overweight or obesity; 11.0% were underweight (CDC, 2007). Among drinkers, women reported reducing their drinking from an average of 4.6 standard drinks/occasion at conception to 3.8 across pregnancy. 305 women (63.5%) reported drinking at least once/month during pregnancy. Of these, women who drank less than once/week consumed 3.2 drinks/occasion on average. Those drinking at least weekly averaged 4.6 drinks/occasion. Larger maternal prepregnancy weight and BMI were both related to number of drinks consumed/occasion (r=.10, p=.031 and r=.13, p=.004, respectively) but not to overall alcohol consumption or frequency of drinking. Smoking was common (62.5%) with 6.9% averaging ≥ 1 pack/day. 86 women (17.9%) reported heavy cocaine use (≥ 2 days/week), but of these only five reported drinking 1 or more drinks/day on average. 30.6% reported marijuana use, with almost 25% reporting monthly use but less than 5% reporting weekly use. Only 7.7% of women reported any opiate use, with 21 (4.4%) using opiates at least once monthly.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| N | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Parity (number of prior pregnancies) | 480 | 1.4 | (1.5) | 0.0 – 10.0 |

| Gestational age at recruitment (week) | 480 | 23.3 | (7.9) | 6.0 – 40.0 |

| Age at delivery (years) | 480 | 26.4 | (6.0) | 14.0 – 43.9 |

| Prepregnancy weight (kg) | 479 | 64.4 | (18.6) | 41.8 – 159.1 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 479 | 24.1 | (6.3) | 15.9 – 58.4 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 53 | (11.0) | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25 – 29.9) | 70 | (14.5) | ||

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 65 | (13.5) | ||

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | 326 | 13.9 | (9.6) | −10.8 – 49.1 |

| Years of school completed | 480 | 11.7 | (1.6) | 6.0 – 18.0 |

| Marital status (married) | 480 | 48 | (10.0) | |

| Socioeconomic statusa | ||||

| Infancy | 399 | 19.9 | (8.4) | 8.0 – 63.0 |

| 7.5-year visit | 336 | 25.7 | (11.1) | 6.0 – 66.0 |

| 14-year visit | 293 | 29.6 | (10.1) | 8.0 – 66.0 |

| Number of stressful eventsb | ||||

| 7.5-year visit | 286 | 6.6 | (3.4) | 0.0 – 23.0 |

| 14-year visit | 281 | 3.6 | (2.4) | 0.0 – 14.0 |

| Perceived life stressb | ||||

| 7.5-year visit | 286 | 20.9 | (16.2) | 0.0 – 125.0 |

| 14-year visit | 281 | 14.2 | (11.0) | 0.0 – 61.0 |

| Maternal prenatal alcohol, smoking, and drug use (Users only) | ||||

| Average oz absolute alcohol (AA) per day | ||||

| At conception | 381 | 1.1 | (2.0) | 0.01 – 24.8 |

| During pregnancy | 371 | 0.3 | (0.6) | 0.01 – 6.5 |

| Average oz AA per drinking day | ||||

| At conception | 381 | 2.3 | (2.8) | 0.1 – 25.6 |

| During pregnancy | 371 | 1.9 | (2.0) | 0.2 – 24.8 |

| Average number drinking days per month | ||||

| At conception | 381 | 12.2 | (8.1) | 4.4 – 30.5 |

| During pregnancy | 371 | 4.3 | (4.7) | 0.2 – 30.5 |

| Cigarettes per day | 300 | 14.1 | (9.8) | 1.0 – 41.0 |

| Marijuana use (days per month) | 147 | 3.0 | (3.3) | 0.1 – 19.2 |

| Cocaine use (days per month) | 150 | 3.8 | (3.7) | 0.1 – 20.0 |

| Opiate use (days per month) | 37 | 2.8 | (4.2) | 0.1 – 22.5 |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Gender (male) | 480 | 276 | (57.5) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (week) | 480 | 39.3 | (1.6) | 32.5 – 43.0 |

| Premature birth (< 37 week) | 480 | 34 | (7.1) | |

| Breastfeeding (breastfed) | 383 | 64 | (16.7) | |

| Weeks breastfed | 64 | 14.3 | (14.5) | 0.3 – 52.6 |

| Birth | ||||

| Birthweight (g) | 480 | 3090.7 | (541.9) | 1560.0 – 4536.0 |

| Low birthweight (<2500 g) | 480 | 62 | (12.9) | |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 480 | −0.7 | (1.0) | −3.2 – 2.2 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 471 | −0.4 | (1.2) | −6.2 – 1.9 |

| Head circumference Z-score | 469 | −0.8 | (0.9) | −5.3 – 1.3 |

| 6.5-month visit | ||||

| Age (months) | 443 | 6.8 | (0.5) | 5.9 – 10.2 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 442 | −0.1 | (1.2) | −7.4 – 3.3 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 441 | −0.3 | (1.1) | −5.6 – 3.2 |

| Weight-for-length Z-score | 441 | 0.3 | (1.4) | −16.7c – 2.9 |

| Head circumference Z-score | 440 | 0.3 | (1.1) | −4.9 – 3.2 |

| 13-month visit | ||||

| Age (months) | 385 | 13.7 | (1.0) | 11.4 – 18.4 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 311 | −0.1 | (1.3) | −5.8 – 4.0 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 364 | 0.02 | (1.1) | −5.2 – 4.1 |

| Weight-for-length Z-score | 310 | 0.3 | (1.2) | −3.3 – 4.3 |

| Head circumference Z-score | 315 | 0.7 | (1.1) | 0.7 – 1.1 |

| 7.5-year visit | ||||

| Age (years) | 336 | 7.7 | (0.3) | 7.2 – 8.9 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 329 | 0.3 | (1.1) | −4.4 – 3.2 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 329 | 0.2 | (1.0) | −4.0 – 3.3 |

| BMI Z-score | 328 | 0.3 | (1.1) | −3.8 – 2.7 |

| Underweight (<5th %ile) | 18 | (5.5) | ||

| Overweight (>85th %ile) | 76 | (23.2) | ||

| Obesity (>95th %ile) | 42 | (12.8) | ||

| Head circumference (cm) | 328 | 51.7 | (1.7) | 47.1 – 57.2 |

| 14-year visit | ||||

| Age (years) | 293 | 14.4 | (0.6) | 13.3 – 16.5 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 288 | 0.9 | (1.2) | −3.8 – 3.7 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 288 | 0.2 | (1.1) | −3.8 – 3.8 |

| BMI Z-score | 288 | 0.9 | (1.0) | −2.3 – 3.0 |

| Underweight (<5th %ile) | 3 | (1.0) | ||

| Overweight (>85th %ile) | 95 | (33.1) | ||

| Obesity (>95th %ile) | 72 | (25.0) | ||

| Head circumference (cm) | 288 | 55.3 | (2.3) | 37.0 – 60.4 |

| 19-year visit: | ||||

| Age (years) | 127 | 19.4 | (0.5) | 18.3 – 21.0 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | 126 | 0.9 | (1.3) | −3.2 – 3.4 |

| Length-for-age Z-score | 126 | 0.3 | (1.1) | −2.8 – 3.2 |

| BMI Z-score | 126 | 0.2 | (1.2) | −2.5 – 2.9 |

| Underweight (<5th %ile) | 2 | (1.6) | ||

| Overweight (>85th %ile) | 54 | (42.9) | ||

| Obesity (>95th %ile) | 34 | (27.0) | ||

| Head circumference (cm) | 126 | 57.0 | (2.1) | 51.5 – 61.7 |

Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975).

Life Events Scale (Holmes and Rahe, 1967).

One child whose mother averaged only 0.15 oz AA during pregnancy (a light drinker) had weight-for-length Z-score −16.7 at 6 months; all others were ≥ −4.0 at 6 months.

Child characteristics

7.1% of the children were preterm (GA < 37 weeks). Relatively few infants were breastfed, and among those breastfeeding, half stopped before 2 months postpartum (Jacobson et al., 1991). Infants were small in weight, length, and head circumference at birth relative to CDC norms (Kuczmarski et al., 2002). More than 10% were low birthweight (<2500 g), with 32.0% small for gestational age (Oken et al., 2003). Mean WAZ and HAZ increased during the course of childhood. Although mean WLZ and BMIZ remained relatively constant, the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased steadily from ages 7.5 to 14 years, with 42.9% meeting criteria for overweight or obesity at age 19. Based on assessments performed at 7.5 years (Jacobson et al., 2004), three children met criteria for a diagnosis of FAS. Baseline demographics including maternal education, socioeconomic status, and parity were not different between children attending the 7.5-year visit and those missing the visit, all ps > .20. Similarly, baseline demographics and life stress events reported at 7.5 and 14 years were not different between those attending the 19-year visit and those missing it, all ps > .15, except for a slight difference in maternal education (11.6 vs. 11.9 years, respectively, p = 0.10). Ns for all visits are summarized in Table S1.

Prenatal alcohol exposure and child growth

As we have reported previously (Jacobson et al., 1994), prenatal alcohol exposure was related to reduced weight, height, and head circumference at birth; effects did not appear to be dose-dependent (i.e., linear) but were seen primarily in infants whose mothers averaged 4 or more standard drinks/day. Postnatally, both average daily maternal alcohol consumption and frequency of drinking across pregnancy were related to longitudinal reductions in weight and height Z-scores (Table 2). Frequency of drinking was also related to reduced weight-for-height and BMI Z-scores. The effects of alcohol exposure on head circumference, adjusting for child sex and age, fell short of conventional levels of statistical significance. When adjusting for birth anthropometric Z-scores in these longitudinal models, the effects of alcohol exposure on weight, height, and weight-for-height were no longer present (all ps>0.20), indicating that the observed postnatal growth restriction was largely the result of growth restriction in utero. These findings were unchanged when the three children with FAS were excluded.

Table 2.

Relation of prenatal alcohol exposure to growth outcomes

| WAZ | HAZ | WLZ or BMI | Head circumference (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | p | βa | p | βa | p | βb | p | |

| Oz AA per day across pregnancy | −.43 | .022 | −.43 | .013 | −.22 | .255 | −.48 | .076 |

| Oz AA per drinking day across pregnancy | .07 | .421 | −.05 | .549 | −.01 | .891 | .04 | .730 |

| Frequency (number of drinking days/month) | −.03 | .006 | −.02 | .022 | −.02 | .041 | −.03 | .071 |

Note. AA = absolute alcohol; WAZ = weight-for-age Z-score; HAZ = height-for-age Z-score; WLZ = weight-for-length Z-score

BMI = body mass index; β = raw (unstandardized) regression coefficient.

Univariate regression analysis.

Multivariable regression analysis adjusting for child sex and age at time of measurement.

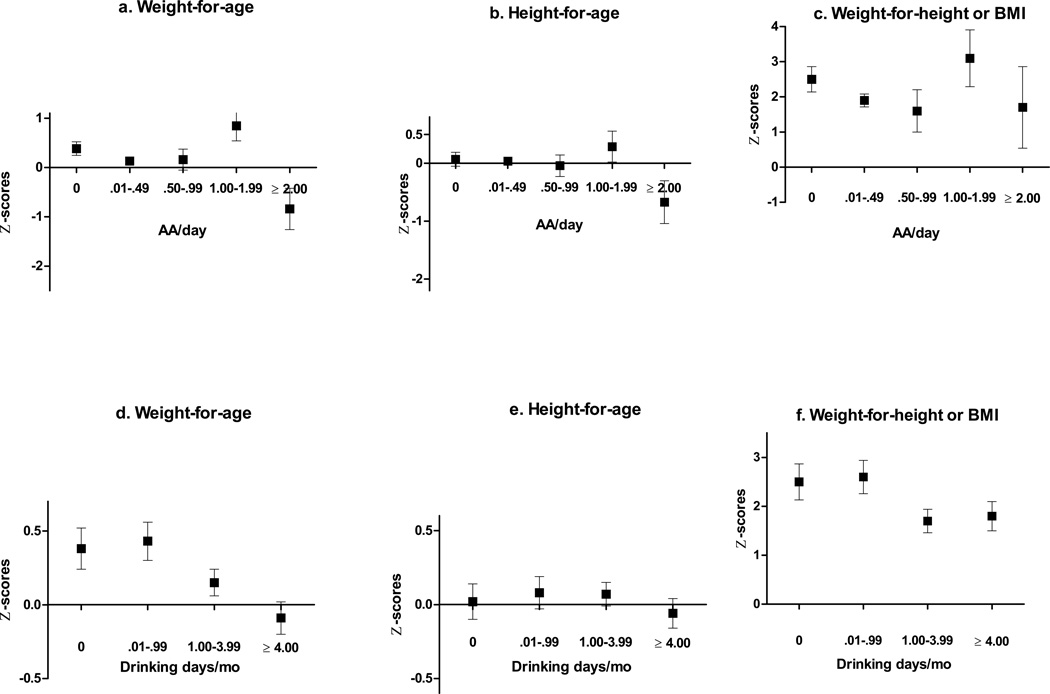

Figures 1a–c display mean WAZ, HAZ, and WLZ-BMI Z-scores at each age across five levels of average daily maternal alcohol consumption. Weight and height Z-scores were reduced for children whose mothers drank 2 oz AA/day or more on average compared with children whose mothers averaged < 2 oz AA daily. Given these threshold effects, the cohort was categorized into heavy vs. non-heavy exposure groups in further analyses, split at the threshold of 2 or more oz AA/day. When compared to other drinkers, mothers of children in this heavy exposure group drank more frequently (M =19.2 vs. 4.0 days/month; t(369)=−10.38, p<.0001), ranging from 6.1 to 30.5 days/month, and drank more/occasion (8.0 vs. 1.8 oz AA; t(369)=9.59, p<.0001). Figures 1 d–f display mean childhood WAZ, HAZ, and WLZ-BMIZ scores across four levels of frequency of maternal drinking. The relation between maternal drinking frequency and WAZ followed a linear dose-dependent pattern; the effect on HAZ was seen primarily in children whose mothers drank 4 or more days/month.

Figure 1.

Mean Z-scores averaged across all ages by maternal AA/day group (a–c) and maternal drinking days per month group (d–f) adjusting for confounders (with SEM bars)

Patterns of fetal alcohol-related growth restriction over time

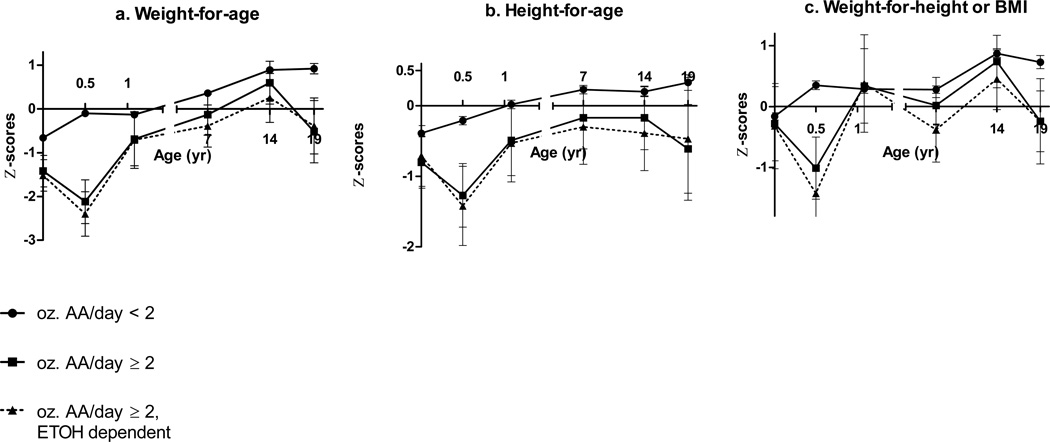

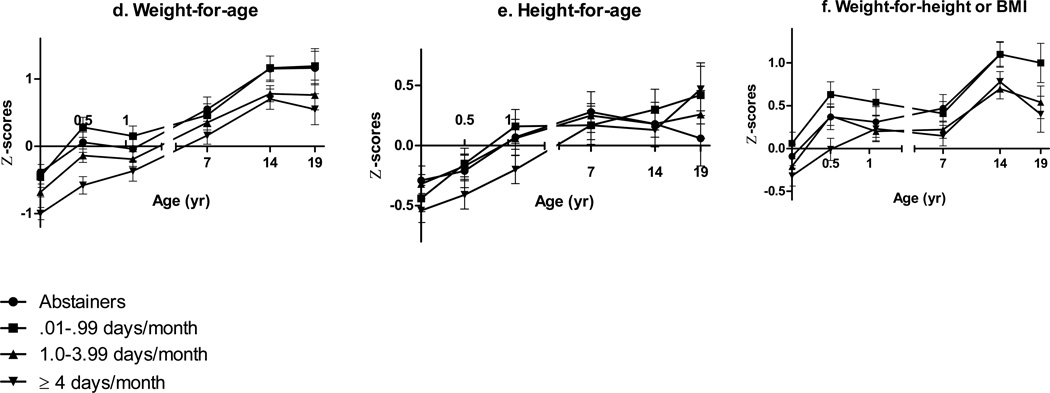

Multivariate regression models using repeated measures revealed interaction effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and child’s age on growth (Table 3). To examine these patterns over time, group means (adjusted for the potential confounders in Table 3) were calculated for each growth outcome at each time point (ANCOVA; Figures 2a–f). WAZ for children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure decreased by 0.9 between birth and 6.5 months compared to an increase of 0.6 among those without heavy exposure (F(1,363)=8.29, p=.004) and increased by 1.4 between 6.5–13 months compared with a decrease of 0.2 among those without heavy exposure (F(1,282)=16.56, p<.0001). This pattern revealed a postnatal delay in weight gain at 6.5 months in the more heavily exposed children that was no longer evident by 13 months. Differences in WAZ, HAZ, and WLZ between children with and without heavy exposure were strongest during infancy and appeared to converge over time. However, when we excluded the only child in the heavy exposure group whose mother did not meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence based on the MAST (score<5), the effects of heavy alcohol exposure on growth were relatively constant throughout childhood (Fig. 2a–c; dotted line). At age 19 years, anthropometric values were available for only three of the children with heavy exposure, all of whom had WAZ and HAZ below the means for the non-heavy exposed group (WAZ F(1,117)=4.23, p=.042; HAZ F(1,117)=2.10, p=.163). The relations of frequency of drinking during pregnancy to WAZ and WLZ during infancy were dose dependent (Figures 2d–f). Differences between exposure groups began to converge at 7.5 years and diverge again at 14 and 19; children whose mothers drank at least monthly had smaller WAZ at ages 14 (F(1,288)=8.63, p=.004) and 19 (F(1,117)=6.62, p=.011). Effects on HAZ were strongest during infancy and waned later in childhood (Figure 2e). There was no evidence of interaction between prenatal alcohol exposure and child age on head circumference.

Table 3.

Interaction of prenatal alcohol exposure and child age

| WAZ | HAZ | WLZ or BMI | Head circumference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | p | βb | p | βc | p | βd | p | |

| Heavy vs. nonheavy exposure | −1.39 | .002 | −1.05 | .007 | −.84 | .047 | −0.95 | .160 |

| Child’s age at measurement (yr) | .06 | <.0001 | .02 | <.0001 | .03 | <.0001 | .06 | <.0001 |

| Interaction term | .04 | .077 | .04 | .028 | .03 | .275 | −.00 | .330 |

| Maternal drinking days/month | −.04 | .002 | −.03 | .012 | −.02 | .047 | −.03 | .101 |

| Child’s age at measurement (yr) | .05 | <.0001 | .01 | .0001 | .03 | <.0001 | .06 | <.0001 |

| Interaction term | .06 | .002 | .09 | <.0001 | .02 | .302 | .00 | .352 |

Note. WAZ = weight-for-age Z-score; HAZ = height-for-age Z-score; WLZ = weight-for-length Z-score

BMI = body mass index; β = raw (unstandardized) regression coefficient.

Adjusted for maternal parity and socioeconomic status.

Heavy vs. non-heavy model is adjusted for socioeconomic status and gestational age at delivery. Maternal drinking days/month model is adjusted for socioeconomic status, gestational age at delivery, maternal parity, and maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy.

Adjusted for maternal parity.

Adjusted for child sex.

Figure 2.

a–c Mean Z-scores at each age-point comparing heavy vs. non-heavy exposure adjusting for confounders (with SEM bars)

d–f Mean Z-scores at each age-point comparing maternal drinking days per month groups adjusting for confounders (with SEM bars

Impact of maternal anthropometry on fetal alcohol-related growth restriction

Lower maternal prepregnancy weight and BMI were associated with greater adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on child WAZ, HAZ, and head circumference in regression analyses with interaction terms (Table 4). In stratified analyses (Table 5), the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on longitudinal WAZ, HAZ, WLZ or BMI, and head circumference were markedly stronger among children born to mothers below the median for prepregnancy weight (59.1 kg). In children whose mothers were smaller, heavy drinking during pregnancy was associated with a weight reduction of 1.7 SD, a height reduction of 1.4 SD, and a reduction in head circumference of 2.4 cm, compared with no reductions in children of heavier mothers. A similar pattern was seen for prepregnancy BMI (median = 22.4). By contrast, maternal weight gain during pregnancy did not moderate the effect of alcohol exposure on growth restriction.

Table 4.

Interaction of maternal prepregnancy anthropometry and prenatal alcohol exposure

| WAZ | HAZ | WLZ or BMI | Head circumference |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | p | βb | p | βc | p | βd | p | |

| Maternal prepregnancy weight | ||||||||

| Heavy vs.non-heavy exposure | −5.97 | .013 | −4.77 | .0001 | −2.83 | .191 | −8.42 | .009 |

| Maternal weight (kg) | .02 | <.0001 | .01 | <.0001 | .01 | <.0001 | .01 | <.0001 |

| Interaction term | .08 | .032 | .07 | .050 | .04 | .283 | .05 | .023 |

| Maternal drinking days/month | −.15 | .002 | −.10 | .020 | −.12 | .008 | −.29 | <.0001 |

| Maternal weight (kg) | .01 | <.0001 | .01 | .003 | .01 | .007 | .00 | .287 |

| Interaction term | .06 | .006 | .04 | .027 | .05 | .018 | .06 | <.0001 |

| Maternal prepregnancy BMI | ||||||||

| Heavy vs. non-heavy exposure | −0.29 | .021 | −.16 | .151 | −.20 | .0815 | −13.37 | .012 |

| Maternal BMI | .04 | <.0001 | .02 | .011 | .03 | <.0001 | .03 | .002 |

| Interaction term | .37 | .0362 | .19 | .216 | .25 | .110 | .56 | .021 |

| Maternal drinking days/month | −.10 | .061 | −.06 | .212 | −.10 | .044 | −.25 | <.001 |

| Maternal BMI | .04 | <.001 | .01 | .086 | .02 | .009 | .01 | .429 |

| Interaction term | .11 | .107 | .07 | .259 | .11 | .080 | .30 | <.001 |

Note. WAZ = weight-for-age Z-score; HAZ = height-for-age Z-score; WLZ = weight-for-length Z-score

BMI = body mass index; β = raw (unstandardized) regression coefficient.

Adjusted for maternal parity and socioeconomic status.

Heavy vs. non-heavy model is adjusted for socioeconomic status and gestational age at delivery.

Adjusted for maternal parity.

Maternal drinking days/month model is adjusted for socioeconomic status, gestational age at delivery, maternal parity, and maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy.

Table 5.

Stratified analyses examining relation of alcohol and postnatal growth by group split at median for maternal prepregnancy anthropometric indices

| WAZ | HAZ | WLZ or BMI | Head circumference | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | 50% | Upper | 50% | Lower | 50% | Upper | 50% | Lower | 50% | Upper | 50% | Lower | 50% | Upper | 50% | |

| βa | p | βa | p | βb | p | βb | p | βc | p | βc | p | βd | p | βd | p | |

| Maternal prepregnancy weight | ||||||||||||||||

| Heavy vs. non-heavy exposure | −1.67 | .003 | −.13 | .822 | −1.38 | .005 | .03 | .948 | −.92 | .117 | −.05 | .920 | −2.38 | .002 | .22 | .785 |

| Maternal drinking days/month | −05 | .007 | .00 | .930 | −.03 | .049 | .00 | .447 | −.04 | .065 | −.00 | .830 | −.10 | <.0001 | .04 | .025 |

| Maternal prepregnancy BMI | ||||||||||||||||

| Heavy vs. non-heavy exposure | −1.71 | .003 | −.12 | .839 | −1.51 | .004 | .22 | .653 | −.94 | .114 | −.07 | .886 | −2.47 | <.001 | .30 | .720 |

| Maternal drinking days/month | −.05 | .002 | .01 | .391 | −.04 | .020 | .02 | .185 | −.04 | .040 | .00 | .819 | −.10 | <.0001 | .06 | .005 |

Note. WAZ = weight-for-age Z-score; HAZ = height-for-age Z-score; WLZ = weight-for-length Z-score; BMI = body mass index

β= raw (unstandardized) regression coefficient.

Adjusted for maternal parity and socioeconomic status.

Heavy vs. non-heavy model is adjusted for socioeconomic status and gestational age at delivery. Maternal drinking days/month model is adjusted for socioeconomic status, gestational age at delivery, maternal parity, and maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy.

Adjusted for maternal parity.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on intrauterine growth restriction persist well into early adulthood. These data are consistent with findings from our heavily exposed Cape Town cohort (Carter et al., In press) in which effects of fetal alcohol exposure on height and weight through middle childhood were similar in magnitude (almost 0.5 SD) to those seen among the more heavily exposed children in this Detroit sample. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure also persisted through adolescence in both the Pittsburgh (Day et al., 2002) and Boston cohorts (Lumeng et al., 2007). These findings are independent of prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and drug use, which were not related to longitudinal growth after adjustment for alcohol exposure. Thus, postnatal growth restriction in children that has been attributed to maternal smoking during pregnancy in prior studies (e.g., Hardy and Mellits, 1973) may have been due in part to unmeasured prenatal alcohol exposure.

The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on postnatal growth were no longer significant after controlling for size at birth, suggesting that they are primarily a consequence of prenatal growth restriction, the effects of which persist well into early adulthood. There was an additional alcohol-related postnatal delay in weight gain at 6.5 months that was no longer present at 13 months. A similar postnatal delay in weight gain was seen in the Cape Town cohort at 13 months (Carter et al., 2012). Low WAZ in that cohort at 6.5 months among infants without prenatal alcohol exposure may have initially obscured the alcohol-related delay in weight gain, and the earlier improvement in weight gain in Detroit may be the result of better nutrition. Further studies are needed to examine the etiology of this alcohol-related growth delay and, in turn, whether it is amenable to intervention.

In analyses examining effects of frequency of maternal drinking on growth, fetal alcohol effects were generally stronger during infancy than in later childhood. This pattern is consistent with Streissguth et al.’s (1991) finding of growth restriction in infancy that improved around time of puberty in the Seattle 500 cohort. However, in the current study, the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth persisted among those whose mothers drank at least monthly and among the heavily exposed children whose mothers met criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence. These data are consistent with the findings in the heavily exposed Cape Town cohort in which fetal alcohol-related growth restriction persisted through 9 years (Carter et al., 2007). Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure also persisted through adolescence in both the Pittsburgh (Day et al., 2002) and Boston cohorts (Lumeng et al., 2007). Because infancy is a critical period for cognitive and psychosocial development, effects of early growth restriction may persist well into adulthood, even in cases where the effects of alcohol on somatic growth wane by adolescence.

The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth were most evident in children whose mothers consumed an average of 4 or more standard drinks/day, consistent with the threshold reported in this cohort during infancy (Jacobson et al., 1994). In contrast, no threshold was identified for growth restriction during infancy when the effects of how often women drank during pregnancy were examined, underscoring the potential effects of even moderate levels of drinking during pregnancy. Later in childhood, persistent reductions in WAZ and BMI Z-scores were most evident among children whose mothers drank above a threshold of at least monthly during pregnancy. Although these mothers consumed <1 drink/day on average, they binge drank, consuming more than 4 drinks/occasion on average. Thus, even occasional exposure to maternal binge drinking during pregnancy may lead to persistent growth restriction. Prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with greater reductions in weight than height (lower weight-for-length and BMI Z-scores), which is consistent with Day et al.’s (2002) finding of reduced skinfold thickness among adolescents with prenatal alcohol exposure. Prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with reduced head circumference at birth, as we have previously reported for this cohort (Jacobson et al., 1994). In longitudinal analyses, these effects persisted over time but fell short of conventional levels of statistical significance. Differences in head circumference between groups may have been obscured by (a) lack of power due to fewer children with very heavy prenatal exposure and/or (b) a true difference that is close to the standard error of measurement for head circumference. The magnitude of the head circumference reduction was similar to our Cape Town cohort, where levels of exposure were very high and the alcohol-related difference in head circumference was 0.9 cm (Carter et al., In press). Among children born to smaller mothers, the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on head circumference were markedly stronger, with heavy exposure resulting in a reduction of 2.4 cm, adjusted for age and sex.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of prenatal maternal weight and BMI on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on childhood growth. In case-control studies in South Africa and Italy, May et al. (2011) found that mothers of school-age children with FASD had lower weight than mothers of non-FASD children in the same communities. In the current study, lower maternal prepregnancy weight and BMI both exacerbated alcohol-related growth restriction. For a given amount of alcohol intake, smaller women have lower volume of distribution and thus are likely to have higher blood alcohol concentrations than larger women, thus increasing exposure to the fetus (Lands, 1998). Alternatively, the protective effects of larger prepregnancy weight may be due to better maternal nutrition. Animal studies have demonstrated interactions between maternal nutrition and alcohol teratogenesis, suggesting that improving maternal prepregnancy diet may mitigate some of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (Weinberg et al., 1990, Shankar et al., 2006, Xu et al., 2006, Thomas et al., 2009, Keen et al., 2010). It is not clear which aspects of nutrition are important (e.g., total calories or intake of certain critical micronutrients), and further studies of maternal nutritional status among heavy drinking pregnant women are needed. Our finding that poor maternal weight gain during pregnancy did not exacerbate the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth suggests that improvements in maternal nutrition may need to occur prior to or early in pregnancy.

This study had limitations common to other longitudinal studies of development. Some children were unable to attend all visits, but our use of regression with repeated measures reduces the impact of missing data points. Even though the mothers were recruited from the same inner-city community, numerous unmeasured environmental, dietary, and genetic influences on postnatal growth and body composition presumably exist in this sample, creating some degree of residual confounding, and noise surrounding estimates of true alcohol exposure to the fetus may obscure some group differences in growth outcomes. However, differences between true and estimated exposure are likely small, given the validity of the interviewing techniques previously demonstrated in this cohort (Jacobson et al., 2002). Although retrospective maternal reports of prepregnancy weight may be affected by recall bias, in other studies using this method, women have tended to underreport weight by only about 1 kg and reported weights correlate highly with actual weights (Troy et al., 1995, Gorber et al., 2007).

Conclusions

This study confirms prior findings of alcohol-related fetal growth restriction that persists through young adulthood. Persistent growth restriction was seen among children whose mothers drank at least monthly or consumed 4 or more standard drinks/day on average. By contrast, alcohol-related growth restriction was less severe in later childhood and adolescence among low-to-moderately exposed children. To our knowledge, this is the first study in humans to demonstrate that smaller maternal prepregnancy weight and BMI exacerbate alcohol-related growth restriction. This interaction may be due to increased fetal exposure attributable to higher blood alcohol levels among smaller women for a given amount of alcohol intake as well as protective effects from better maternal nutrition. Further studies are needed to examine the potential of improved maternal nutritional intake for ameliorating the adverse effects of fetal alcohol exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

The Detroit Longitudinal Cohort Study was funded by grants from NIH/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA06966, R01 AA09524, and P50 AA0706), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA021034), National Center for Research Resources (Vanderbilt CTSA grant UL1 RR024975), and supplemental funding from the Joseph Young, Sr., Fund from the State of Michigan. RCC’s participation was supported, in part, by NIAAA K23 AA020516 and NIH KL2 RR025757 (Harvard Catalyst Clinical and Translational Science Program). We thank Erawati Bawle, Sterling Clarren, and Kenneth L. Jones, for their assistance in the diagnosis of FAS. We also thank Renee Sun, Neil Dodge, Julie Croxford, Lisa Chiodo, Chie Yumoto, Audrey Tocco, Douglas Fuller, and other members of our research staff for their help data collection and processing. We thank the mothers and children for long-term commitment to and participation in the Detroit Longitudinal Cohort Study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Ballard JL, Novak KK, Driver M. A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. J Pediatr. 1979;95:769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman RS, Stein LI, Newton JR. Measurement and interpretation of drinking behavior. I. On measuring patterns of alcohol consumption. II. Relationships between drinking behavior and social adjustment in a sample of problem drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1975;36:1154–1172. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RC, Jacobson JL, Molteno CD, Jiang H, Meintjes EM, Jacobson SW, Duggan CP. Effects of heavy prenatal alcohol exposure and iron deficiency anemia on child growth and body composition through age 9 years. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01810.x. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RC, Jacobson SW, Molteno CD, Jacobson JL. Fetal alcohol exposure, iron-deficiency anemia, and infant growth. Pediatrics. 2007;120:559–567. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0151. PMID: 17766529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Anthropometry Procedures Manual, in Series National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Anthropometry Procedures Manual. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Brown RT, Smith IE, Platzman KA, Erickson S, Falek A. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure at school age. I. Physical and cognitive development. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1991;13:357–367. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90084-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day N, Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, Richardson G, Robles N, Taylor P. The effects of prenatal tobacco and marijuana use on offspring growth from birth through 3 years of age. Neurotoxicol teratol. 1992;14:407–414. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90051-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Leech SL, Richardson GA, Cornelius MD, Robles N, Larkby C. Prenatal alcohol exposure predicts continued deficits in offspring size at 14 years of age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1584–1591. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034036.75248.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Richardson G, Robles N, Sambamoorthi U, Taylor P, Scher M, Stoffer D, Jasperse D, Cornelius M. Effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and morphology of offspring at 8 months of age. Pediatrics. 1990;85:748–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8:307–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene T, Ernhart CB, Sokol RJ, Martier S, Marler MR, Boyd TA, Ager J. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Preschool Physical Growth - a Longitudinal Analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:905–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb05186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. Introduction to stratified analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JB, Mellits ED. Effect on child of maternal smoking during pregnancy. Lancet. 1973;1:719–720. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status [unpublished manuscript]., in Series Four Factor Index of Social Status [unpublished manuscript] New Haven: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Muckle G, Kaplan-Estrin M, Ayotte P, Dewailly E. Beneficial effects of a polyunsaturated fatty acid on infant development: evidence from the Inuit of Arctic Quebec. J Pediatr. 2008a;152:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Ager JW, Shankaran S. Effects of alcohol use, smoking, and illicit drug use on fetal growth in black infants. J Pediatr. 1994;124:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Chiodo LM, Sokol RJ, Jacobson JL. Validity of maternal report of prenatal alcohol, cocaine, and smoking in relation to neurobehavioral outcome. Pediatrics. 2002;109:815–825. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL, Frye KF. Incidence and correlates of breast-feeding in socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Pediatrics. 1991;88:728–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL, Sokol RJ, Chiodo LM, Corobana R. Maternal age, alcohol abuse history, and quality of parenting as moderators of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on 7.5-year intellectual function. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1732–1745. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145691.81233.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Stanton ME, Molteno CD, Burden MJ, Fuller DS, Hoyme HE, Robinson LK, Khaole N, Jacobson JL. Impaired eyeblink conditioning in children with fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008b;32:365–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen CL, Uriu-Adams JY, Skalny A, Grabeklis A, Grabeklis S, Green K, Yevtushok L, Wertelecki WW, Chambers CD. The plausibility of maternal nutritional status being a contributing factor to the risk for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: the potential influence of zinc status as an example. Biofactors. 2010;36:125–135. doi: 10.1002/biof.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lands WE. A review of alcohol clearance in humans. Alcohol. 1998;15:147–160. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(97)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Cabral HJ, Gannon K, Heeren T, Frank DA. Pre-natal exposures to cocaine and alcohol and physical growth patterns to age 8 years. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manari AP, Preedy VR, Peters TJ. Nutritional intake of hazardous drinkers and dependent alcoholics in the UK. Addict Biol. 2003;8:201–210. doi: 10.1080/1355621031000117437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP. Maternal risk factors for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, Hendricks LS, Snell CL, Tabachnick BG, Stellavato C, Buckley DG, Brooke LE, Viljoen DL. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:738–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers Y, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Hoffman HJ, Cutter GR. The relationship between maternal and neonatal anthropometric measurements in term newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:192–196. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00364-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan FV, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Williams GM, Bor W. Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and physical outcomes up to 5 years of age: a longitudinal study. Early Hum Dev. 2003;71:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(03)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Streissguth AP. Prenatal alcohol exposure, birthweight, and measures of child size from birth to age 14 years. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1421–1428. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar K, Hidestrand M, Liu X, Xiao R, Skinner CM, Simmen FA, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Physiologic and genomic analyses of nutrition-ethanol interactions during gestation: Implications for fetal ethanol toxicity. Exp Biol Med. 2006;231:1379–1397. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Aase JM, Clarren SK, Randels SP, LaDue RA, Smith DF. Fetal alcohol syndrome in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 1991;265:1961–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Martin DC, Martin JC, Barr HM. The Seattle Longitudinal Prospective-Study on Alcohol and Pregnancy. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1981;3:223–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Abou EJ, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates the adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on development in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2009;31:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Thomas JD. Perinatal choline supplementation mitigates trace eyeblink conditioning deficits associated with 3rd trimester alcohol exposure in rodents, in Series Perinatal choline supplementation mitigates trace eyeblink conditioning deficits associated with 3rd trimester alcohol exposure in rodents. San Diego: Society for Neuroscience; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:570–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, D’Alquen G, Bezio S. Interactive effects of ethanol intake and maternal nutritional status on skeletal development of fetal rats. Alcohol. 1990;7:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer BJ. Statistical principles in experimental design. 2d ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Li Y, Tang Y, Wang J, Shen X, Long Z, Zheng X. The maternal combined supplementation of folic acid and Vitamin B(12) suppresses ethanol-induced developmental toxicity in mouse fetuses. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Tang Y, Li Y. Effect of folic acid on prenatal alcohol-induced modification of brain proteome in mice. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:455–461. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507812074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumoto C, Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL. Fetal substance exposure and cumulative environmental risk in an African American cohort. Child Dev. 2008;79:1761–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.