Abstract

Objective

To describe patients with progranulin gene (GRN) mutations and evidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology

Design

Two case reports and literature review

Setting

University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center

Patients

Two unrelated patients with GRN mutations

Results

One patient presented at age 65 with a clinical syndrome suggestive of AD and showed evidence of amyloid aggregation on positron emission tomography. Another patient presented at age 54 with logopenic progressive aphasia and at autopsy showed both frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions and AD.

Conclusions

In addition to autosomal-dominant frontotemporal lobar degeneration, mutations in GRN may be a risk factor for AD clinical phenotypes and neuropathology.

Introduction

One of the challenges facing clinicians who evaluate patients with dementia is determining what clinical syndrome best fits with the patient’s presentation and then predicting the most likely underlying molecular pathology. While clinical syndromes often help with this prediction, there is still variability between syndrome and pathology. The term frontotemporal dementia (FTD) refers to a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes featuring changes in personality, behavior, or language. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) refers to a collection of pathologic diagnoses that can cause these clinical syndromes. Three major genes have been implicated in autosomal dominant FTD: microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT), progranulin (GRN), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72). While mutations in GRN have been described as causing a variety of clinical syndromes, including one suggesting Alzheimer’s disease (AD), it is thought these various presentations all result from TDP-43 pathology. Here we present two patients who suggest GRN mutations may also be a risk factor for AD pathology.

Report of Case #1

A 65 year-old right-handed man presented with three years of slowly progressive cognitive changes. His first symptom was misplacing personal items. He retired and attempted to move his office into his home, but ultimately left everything packed in boxes on the floor. Subsequently, he had several minor motor vehicle accidents and exhibited poor financial judgment, borrowing up to $150,000 and forgetting to file his taxes. His memory for recent events became impaired and he developed word finding difficulties. He angered more easily and compulsively checked door locks. There was no behavioral disinhibition, apathy, loss of empathy, or change in food preferences.

On examination, he asked repetitive questions, was suspicious of the examiner, and made phonemic paraphasic errors in speech. He had mild bilateral agraphesthesia. He scored 17/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)1. Detailed neuropsychological testing revealed poor verbal and visual memory, confrontational naming, and executive function with relative preservation of visuospatial skills (Table).

Table.

Neuropsychological Testing

| Normal values by age and education for case 1* (SD) | Case 1 (age 65) | Normal values by age and education for case 2* (SD) | Case 2 (age 54) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | MMSE (max 30) | ----- | 17 | ----- | 14 |

| Memory | CVLT short form delayed recall (max 9) | 7.8 (1.4) | 0 | 7.9 (1.5) | 0 |

| Recognition (max 9) | 8.7 (0.5) | 3 | 8.8 (0.4) | 6 | |

| Recall false positives | 0.6 | 12 | ----- | 3 | |

| Benson figure delayed recall (max 17) | 11.5 (2.8) | 0 | 12.6 (2.3) | 12 | |

| Visuospatial | Benson figure copy (max 17) | 15.5 (1.1) | 16 | 15.5 (1.1) | 15 |

| Language | Modified BNT (max 15) | 14.3 (0.8) | 11 | 14.5 (0.9) | 2 |

| BNT Multiple choice | ----- | 2 | ----- | 11 | |

| Repetition (max 5) | 4.6 (0.6) | 1 | 4.7 (0.7) | 1 | |

| Sentence comprehension (max 5) | ----- | 5 | ----- | 1 | |

| PPVT-R (max 16) | 15.6 (0.8) | 15 | 15.7 (0.8) | 6 | |

| Executive | Digit span backwards | 5.8 (1.2) | 3 | 5.4 (1.3) | 2 |

| Phonemic fluency (D word generation) | 16.3 (4.5) | 13 | 15.0 (3.9) | 1 | |

| Semantic fluency (animal generation) | 23.5 (5.0) | 12 | 22.7 (4.7) | 3 |

Age-adjusted normal values derived from University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center cohort

MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination, CVLT=California Verbal Learning Test, BNT=Boston Naming Test, PPVT=Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test

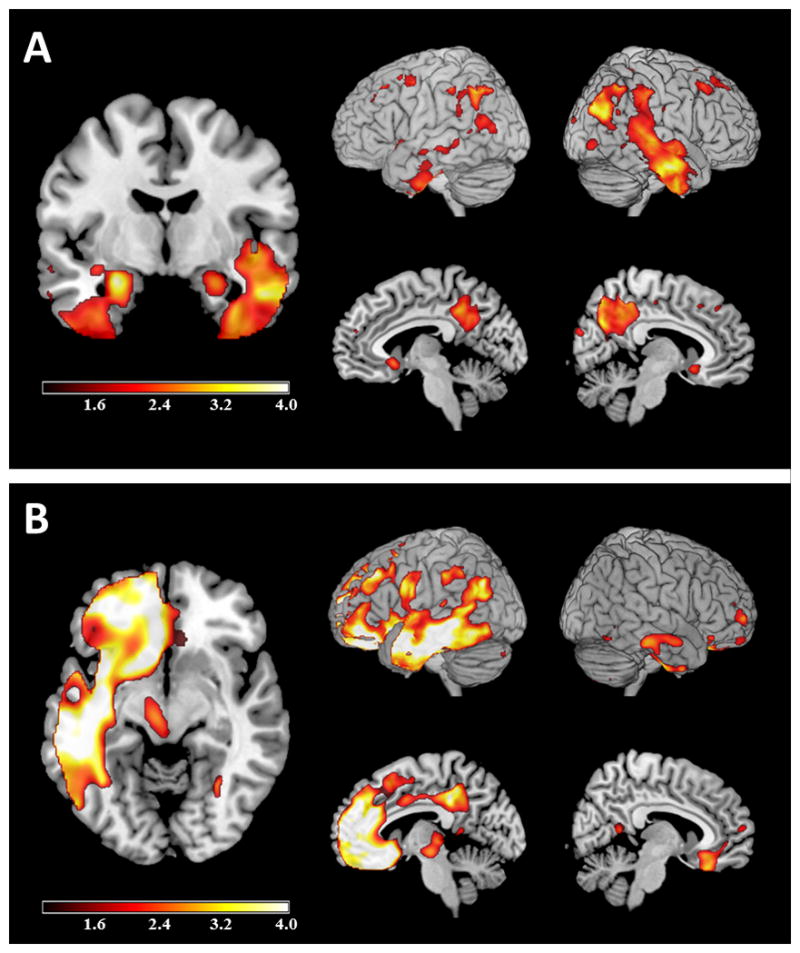

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM)2 was performed on the patient’s 3 T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Pre-processing included segmentation into gray and white matter, alignment and warping with DARTEL 3, normalization to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, modulation and smoothing with an 8 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. Single-subject VBM of combined gray and white matter segmentations was compared with 30 healthy control subjects matched for sex, age, and scanner. Age and total intracranial volume were included as covariates in the regression. Results, displayed in Figure 1A at a threshold of p<0.05 (uncorrected), showed atrophy of medial and lateral temporal and parietal lobes, right greater than left. Based on his clinical presentation, neuropsychological testing, and imaging he was diagnosed with AD.

Figure 1.

Voxel-based morphometry. Single subject voxel-based morphometry of Case 1 (A) and Case 2 (B), uncorrected for multiple comparisons at p<0.05, displayed as T map (1<T<4) and overlaid on MNI template brain. Images are displayed in neurological convention.

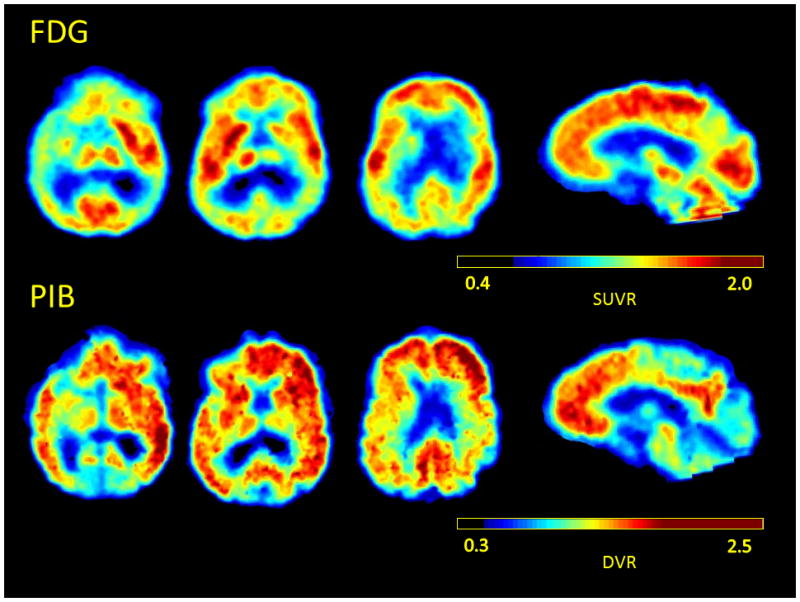

Positron emission tomography with the beta-amyloid tracer Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB-PET) was positive for cortical tracer binding, and PET with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) showed hypometabolism in bilateral temporoparietal cortex (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PET imaging of case 1. (top) FDG-PET showing bilateral temporoparietal hypometabolism and (bottom) Pittsburgh compound B (PiB-PET) image of Case 1 showing amyloid tracer binding.

The patient had a family history of FTD in three maternal relatives. His father had late-life dementia and paternal grandmother was diagnosed with AD. Genetic testing revealed that the patient carried a the same novel mutation in GRN as his affected maternal family members, an octanucleotide insertion in the coding region (c.1263_1264insGAAGCGAG) causing frameshift and premature translation termination, predicted to result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype was E3/E4.

Report of Case #2

A 54 year-old woman presented for evaluation due to one year of progressive language impairment involving difficulties with word finding, remembering names, and expressing herself. Her family described her speech as occasionally nonsensical “like a word salad.” Within a few months she developed difficulty writing, spelling, and decreased speech output. There were no reported problems with recognizing words. Memory complaints were minimal and other than anxiety there was no change in personality or behavior. She had some difficulty with navigation but did not get lost, and there were no motor symptoms.

Her examination was notable for long word-finding pauses and sparse speech mostly consisting of single words and short phrases. There were no articulation problems. She could follow simple commands but had difficulty with complex instructions. She scored 14/30 on the MMSE and on neuropsychological testing she displayed poor verbal memory (that benefitted from recognition), impairment in working memory and executive functions, and language impairment including impairment in repetition, comprehension of syntactically complex sentences, confrontational naming (that benefitted from multiple choice), and verbal fluency (Table).

VBM was performed on her 1.5 T MRI (pre-processing and analysis as in Case 1) and was compared against 16 controls matched as described above (see Figure 1B). There was asymmetric atrophy involving the left temporal lobe, left medial and inferior frontal regions, and left inferior parietal lobe.

She had a family history of dementia including a father who died mute at 65, and a paternal grandmother and brother with a diagnosis of FTD. Her genetic testing revealed a novel GRN mutation, affecting the first protein residue (g.1A>T, p.M1?). Other distinct pathogenic mutations of the same residue have been reported (g.1A>G, p.M1?, PMID: 18245784, g.2T>C, p.M1?, PMID: 16862116, 16950801, and g.3G>A, p.M1?, PMID: 16862115). Her APOE genotype was E3/E4.

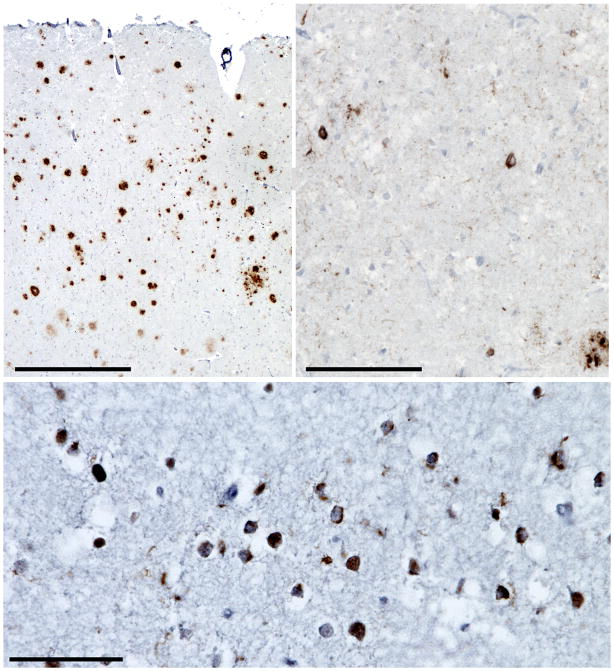

The patient died at age 55, and an autopsy was performed eight days post-mortem. The entire brain showed advanced autolysis, which precluded meaningful observations about cerebral atrophy and limited immunohistochemical analysis. Nonetheless, immunohistochemistry for beta-amyloid (3FR antibody, anti-mouse, 1:250, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), hyperphosphorylated tau (PHF-1 antibody, anti-mouse, 1:250, courtesy Peter Davies), and TDP-43 (anti-rabbit, 1:2000, Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL, USA) was performed on a subset of regions showing relative tissue integrity, including medial temporal lobe, middle frontal gyrus, pre- and post-central gyri, angular gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, and lateral occipital cortex. These analyses revealed moderate to frequent neuritic amyloid plaques (Figure 3A) in all regions examined and moderate to frequent tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles in medial temporal and neocortical regions (Figure 3B) but not primary sensorimotor cortex, consistent with NIA-Reagan criteria for high likelihood AD4 and a Braak AD stage of V.5 In addition, we observed superficial greater than deep laminar TDP-43 pathology consisting of moderate to frequent small round or crescentic neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions and neuropil threads (Figure 3C) accompanied by scarce neuronal nuclear inclusions and glial cytoplasmic inclusions (not pictured), consistent with FTLD-TDP, harmonized Type A,6 the subtype seen in GRN mutation carriers.

Figure 3.

Pathological findings for case 2. In the angular gyrus, (A) frequent amyloid-beta positive neuritic plaques (3F4 antibody, hematoxylin counterstain) and (B) sparse to moderate neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads are seen (PHF-1 antibody, hematoxylin counterstain). (C) Dorsolateral frontal cortex shows frequent TDP-43-immunoreactive crescentic or compact neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions with surrounding wispy neuropil threads, consistent with FTLD-TDP, Type A. Scale bars indicated 500 μM (A), 100 μM (B), and 50 μM (C).

Comment

We present two patients with a clinical presentation consistent with AD, one an amnestic type, and the other suggestive of logopenic progressive aphasia, a syndrome typically caused by AD pathology.7 One patient had a positive amyloid PET scan demonstrating fibrillary amyloid pathology suggestive of AD and the other had autopsy confirmation of AD pathology. Notably, both patients harbored a GRN mutation, which predicts underlying FTLD-TDP pathology rather than AD.

GRN mutations have been associated with several clinical syndromes including behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), nonfluent primary progressive aphasia, and corticobasal syndrome.8 Prior studies have also noted that 9–17% of GRN mutations carriers may present with an AD phenotype.8,9 While pathologic validation is lacking in most cases, one such patient had both AD and FTLD-TDP at autopsy,10 and another showed an AD-like CSF biomarker profile with an AD-like syndrome (low Aβ42 and elevated total tau).11 Other studies have indicated that polymorphisms in GRN modify the risk of developing AD.12–14 As prior clinicopathological series of GRN have shown only rare evidence of co-pathology with AD,9,10 if there is a risk of AD conferred by alterations in GRN, the association is less direct than with FTLD.

Prior data on the influence of APOE status on clinical phenotype in GRN carriers has been mixed, with one study showing early memory problems in E4 allele carriers,9 and two other studies showing no clear modulatory effect on clinical symptoms.15,16 Both patients in this report were heterozygous for the APOE4 allele. It is possible that AD pathology found in these patients was strictly due to APOE4 status, as the prevalence of amyloid deposition (as detected by PiB-PET) is ~10% in 45–59 year-old cognitively normal E4-carriers, and 37% in 60–69 year-old carriers.17 On the other hand, the early age of symptom onset and the AD-like clinical syndrome and atrophy pattern, as well as the advanced neurofibrillary pathology (Braak stage V) seen in Case 2 argue that AD contributed to and perhaps was the main cause of dementia.

GRN mutations are thought to lead to neurodegeneration via haploinsufficiency, though the direct molecular link to TDP-43 translocation and aggregation remains unclear. Recent theories have focused on the anti-inflammatory properties of the progranulin protein.18 GRN mutations result in haploinsufficiency of functional progranulin, which might then result in a pro-inflammatory state. Patients with GRN mutations have been shown to have elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6).19 Functional progranulin promotes an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in macrophages20 which would be decreased in haploinsufficiency. Progranulin interacts with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors, thereby antagonizing TNFα activity.21 In a state of progranulin deficiency relative TNFα activity is therefore increased.

This pro-inflammatory state might predispose not only to development of FTLD, but to other forms of neurodegeneration. AD has also been linked to increased expression of inflammatory cytokines,22 and microglial activation has been observed in AD post-mortem23 and in-vivo.24 Whether this activity is detrimental or protective and primary or secondary has been debated, but there is evidence suggesting that high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines might decrease phagocytosis of beta amyloid by microglia.25 An increase in TNFα is associated with cognitive decline in AD.26 In mouse models of AD, TNFα is implicated in enhanced amyloid production,27 tau hyperphosphorylation and cell death,28 and countering TNFα improves both symptoms and pathology.29,30 Beta amyloid aggregation in mouse hippocampus and cortex has also been induced by inflammation.31

In AD, abnormal TDP-43 staining is seen in up to 34% of cases.32 In most cases of comorbid AD/TDP, TDP inclusions are restricted to the medial temporal lobe, but a minority of cases shows a more widespread deposition pattern consistent with FTLD-TDP Type A, the same pattern associated with GRN cases.33 The molecular links between TDP-43 and AD pathologies are not known. One study found elevated TDP-43 levels in an AD mouse model that correlated with Aβ oligomers; decreasing Aβ42 levels normalized TDP-43 in these mice.34 Whether this relationship could be bidirectional and TDP-43 levels may contribute to Aβ deposition as well is a topic for further investigation.

The present cases add support to the association between GRN and AD. As pathology from more cases becomes available, the strength and the frequency of this association will be clarified.

Acknowledgments

Funding support for this study came from the Consortium for Frontotemporal Research, John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation, Larry Hillblom Foundation, James S McDonnell Foundation, and NIH (grants P50AG023501, P01AG019724, P50AG1657303, NIA K23-AG031861, R01AG040311, R01 AG026938, T32AG23481, and RO1AG032306).

Footnotes

Author Disclosures

Dr. Perry has no conflicts and is funded by T32 AG23481.

Dr. Yokoyama has no conflicts and is funded by a Diversity Supplement through P50AG03006 (PI: Miller).

Mr. Lee and Ms. Karydas do not have any conflicts or disclosures to report.

Dr. Lehmann has no conflicts of interest. She is funded by the Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Dr. Rabinovici has no conflict of interest. He is funded by NIA K23-AG031861.

Dr. Geschwind has no conflicts of interest. He has received institutional support from Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center of California (ARCC) grant 03-7527 and R01 AG026938.

Dr. Coppola has no conflicts of interest. He is funded by R01 AG026938.

Dr. Miller serves as board member on the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation and Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, serves as a consultant for TauRx, Ltd., Allon Therapeutics, the Tau Consortium and the Consortium for Frontotemporal research, The Siemens MIBR (Molecular Imaging Biomarker Research) Alzheimer’s Advisory Group, has received institutional support from Novartis, and is funded by NIH grants P50AG023501, P01AG019724, P50 AG1657303, and the state of CA.

Dr. Seeley is funded by NIH grants P50 AG1657303, the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Disease Foundation, Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, James S. McDonnell Foundation, Larry Hillblom Foundation, has received support for travel by the Alzheimer’s Association, received payment for lectures by the Alzheimer’s Association, American Academy of Neurology and Novartis Korea, and has served on advisory boards for Bristol Myers-Squibb.

Dr. Grinberg has no conflicts of interest and is supported by John Douglas French Alzheimer’s foundation, NIH P50 AG023501-06 and 1R01AG040311-01 and 2 P50 AG023501-06.

Dr. Rosen has no conflicts of interest and is supported by RO1AG032306 and R01AG030688.

References

- 1.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state” : A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11(6 Pt 1):805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38(1):95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4 Suppl):S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Baborie A, et al. A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(1):111–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0845-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesulam M, Wicklund A, Johnson N, et al. Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(6):709–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Hannequin D, et al. Phenotype variability in progranulin mutation carriers: a clinical, neuropsychological, imaging and genetic study. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):732–746. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rademakers R, Baker M, Gass J, et al. Phenotypic variability associated with progranulin haploinsufficiency in patients with the common 1477C-->T (Arg493X) mutation: an international initiative. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(10):857–868. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, Ahmed Z, Katsuse O, et al. Neuropathologic features of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions with progranulin gene (PGRN) mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(2):142–151. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31803020cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Engelborghs S, et al. Genetic variability in progranulin contributes to risk for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;71(9):656–664. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319688.89790.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenoglio C, Galimberti D, Cortini F, et al. Rs5848 variant influences GRN mRNA levels in brain and peripheral mononuclear cells in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(3):603–612. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MJ, Chen TF, Cheng TW, Chiu MJ. rs5848 variant of progranulin gene is a risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the Taiwanese population. Neurodegener Dis. 2011;8(4):216–220. doi: 10.1159/000322538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanathan J, Makinen P, Helisalmi S, Haapasalo A, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. An association study between granulin gene polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease in Finnish population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B(5):747–750. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruni AC, Momeni P, Bernardi L, et al. Heterogeneity within a large kindred with frontotemporal dementia: a novel progranulin mutation. Neurology. 2007;69(2):140–147. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265220.64396.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, et al. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(20):2988–3001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward ME, Miller BL. Potential Mechanisms of Progranulin-deficient FTLD. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45(3):574–582. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9622-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossu P, Salani F, Alberici A, et al. Loss of function mutations in the progranulin gene are related to pro-inflammatory cytokine dysregulation in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:65. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin F, Banerjee R, Thomas B, et al. Exaggerated inflammation, impaired host defense, and neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207(1):117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang W, Lu Y, Tian QY, et al. The growth factor progranulin binds to TNF receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science. 2011;332(6028):478–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1199214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan ZS, Beiser AS, Vasan RS, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Study. Neurology. 2007;68(22):1902–1908. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263217.36439.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes A, Thaker U, Iwatsubo T, Pickering-Brown SM, Mann DM. Pathological relationships between microglial cell activity and tau and amyloid beta protein in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2002;331(3):171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, et al. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):461–467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(33):8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, et al. Systemic inflammation and disease progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73(10):768–774. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b6bb95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto M, Kiyota T, Horiba M, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulate amyloid-beta plaque deposition and beta-secretase expression in Swedish mutant APP transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(2):680–692. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janelsins MC, Mastrangelo MA, Park KM, et al. Chronic neuron-specific tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression enhances the local inflammatory environment ultimately leading to neuronal death in 3xTg-AD mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(6):1768–1782. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He P, Zhong Z, Lindholm K, et al. Deletion of tumor necrosis factor death receptor inhibits amyloid beta generation and prevents learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(5):829–841. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi JQ, Shen W, Chen J, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha reduces amyloid plaques and tau phosphorylation and induces CD11c-positive dendritic-like cell in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse brains. Brain Res. 2011;1368:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JW, Lee YK, Yuk DY, et al. Neuro-inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment through enhancement of beta-amyloid generation. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 immunoreactivity in AD modifies clinicopathologic and radiologic phenotype. Neurology. 2008;70(19 Pt 2):1850–1857. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304041.09418.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uryu K, Nakashima-Yasuda H, Forman MS, et al. Concomitant TAR-DNA-binding protein 43 pathology is present in Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration but not in other tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(6):555–564. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817713b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caccamo A, Magri A, Oddo S. Age-dependent changes in TDP-43 levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease are linked to Abeta oligomers accumulation. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]