Abstract

Background

We have recently determined HCV isolates among volunteer blood donors and IDUs in southern China and revealed the genotype distribution patterns not only different between the two studied cohorts but also from what we have sampled in 2002. A changed pattern could have also occurred among patients with liver disease.

Materials/Methods

Both E1 and NS5B sequences of HCV were characterized among 393 patients with liver disease followed by phylogenetic analysis.

Results

Six HCV genotypes, 12 subtypes (1b: 65.9%, 6a: 17.1%, 2a: 7.4%, 3a: 3.6%, 3b: in 3.3%, 6e: 0.76%, and 1a, 1c, 2b, 2f, 4d, and 5a each 0.25%), and two novel genotype 6 variants were classified, showing the greatest complexity of HCV hitherto found in China. Although the predominance of 1b followed by 6a is largely consistent with what we have sampled in 2002, the identification of single isolates of 1c, 2f, 4d, 5a, and two novel HCV-6 variants were first reported. Excluding 4d from a European visitor, all the others were from Chinese patients. Since the 6a proportion (17.1%, 67/393) was unexpectedly lower than what we have recently detected among blood donors (34.8%, 82/236) and IDUs (51.5%, 70/136), further statistical analyses were conducted. Comparison of the mean ages showed that among the 393 patients, those infected with 1b were significantly (6.7 years) older than those with 6a, while the 393 patients as a whole were significantly older than the 236 blood donors (8.4 years) and 136 IDUs (12.6 years) we have recently reported. Explanations are that younger individuals had higher proportions of 6a infections while patients with liver disease could have acquired their infections earlier than volunteer blood donors and IDUs.

Conclusion

Among 393 patients with liver disease, a great diversity in HCV was detected, which reflects a constantly changing pattern of HCV genotypes in China over time.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, genetic sequence, phylogenetic tree, genotype

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is classified into six genotypes and >90 subtypes showing varied geographic distribution patterns. For example, genotypes 1, 2, and 3 are globally epidemic, genotypes 4 and 5 are prevalent in Africa, while genotype 6 is almost exclusive in Southeast Asia.1,2 Evidence suggests that different genotypes have also spread among different population subsets and are associated with different epidemiological factors.3-5 The routes of transmission, such as the use of blood products, hemodialysis, blood transfusion, unsafe medical practices, injection drug use (IDU), and other parenteral exposures, are all related to HCV genotypes.6-10 Thus, it is necessary to fully understand their epidemiological features and constantly changing distribution patterns as a result of modern transmission and increasing global travels.

Guangdong province, located in southern China, plays a critical role in leading the country’s economic development.11 However, this has also brought about many side effects, such as the increasing drug use, drug trafficking, prostitution, unsafe medical practices, and millions of migrant laborers living in suboptimal hygiene conditions. All of these have contributed to a growing number of viral infections. According to the CNKI (National Knowledge Infrastructure, http://tongji.cnki.net/kns55/index.aspx) data, the HCV-related morbidity in this province has been constantly rising, from 0.89 per million people in 2003 to 13.19 in 2009 that is higher than the national average.

We have recently characterized HCV among volunteer blood donors and IDUs in Guangdong province and revealed the patterns different between them and from that we have sampled in 2002.11-13 Since in the recent decade the population composition in Guangdong province has greatly changed as a result of the fast economic development attracting a large number of immigrants and migrants, a changed pattern of HCV genotypes could have also occurred among patients with liver disease. Therefore, we characterized HCV among 393 such patients.

RESULTS

Patients and detected HCV subtypes

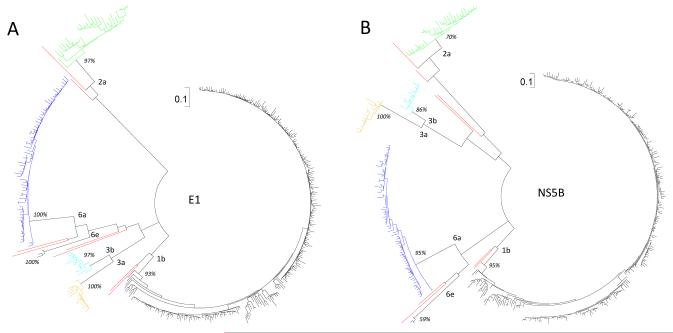

Both E1 and NS5B sequences of HCV were determined from 393 patients with liver disease: 239 (60.8%) men and 154 (39.2%) women. Excluding a Caucasian, all others were Chinese Han ethnicity. Their ages varied from 8 to 82 with a mean age of 43.1 (SD=16.8). The following HCV assigned subtypes were detected: 1b in 259 (65.9%), 6a in 67 (17.1%), 2a in 29 (7.4%), 3a in 14 (3.6%), 3b in 13 (3.3%), and 6e in 3 (0.76%) (Figure 1A). In addition, single 1a, 1c, 2b, 2f, 4d, and 5a isolates were identified, each from a man of 57, 40, 50, 73, 62, and 52 years old, respectively. Furthermore, new genotype 6 variants were detected in a 58-year-old man and a 63-year-old woman (an overseas Chinese living in Myanmar). However, both variants failed to classify into any known subtypes (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Two circular ML trees reconstructed for the 393 partial E1 (A) and NS5B (B) region sequences, corresponding to the nucleotide numbering of 869-1289 and 8276-8615, respectively, in the H77 genome. Subtype designations are given at the internal nodes and bootstrap values shown in percentages. A scale in the upper middle of each tree measures 0.1 nucleotide substitutions per site. Initially, a large number of reference sequences were included for genotyping the 393 isolates. However, to reduce the taxa number shown in the trees, all the reference sequences are removed after genotyping.

Table 1.

Comparison of the 393 patients with 136 IDUs and 236 blood donors recently reported.

| Genotype | 1a | 1b | 1c | 2a | 2b | 2f | 3a | 3b | 4d | 5a | 6a | 6e | 6n | 6 new | Mixed | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Total | 1 | 259 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 67 (17.1%) # | 3 | 2 | 393 | ||

| Female | 115 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 154 | |||||

| Male | 1 | 144 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 2 | 1 | 239 | |||

| Age | 47 | 43.9±18.1† | 40 | 50.9±16.7 | 50 | 73 | 38.0±11.5†‡ | 39.0±7.2†‡ | 62 | 52 | 37.2±11.1†‡ | 39.3±6.0 | 60.5±3.5 | 43.1±16.8¶ | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| IDUs 11 | Total | 13 | 42 | 3 | 70 (51.5%) # | 8 | 136 | ||||||||||

| Female | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 13 | 40 | 3 | 67 | 8 | 131 | |||||||||||

| Age | 36.7±7.9 | 32.6±5.1 | 35.3±8.5 | 34.8±8.0 | 34.7±7.2¶ | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Donors 12 | Total | 3 | 97 | 18 | 15 | 17 | 82 (34.8%) # | 2 | 2 | 236 | |||||||

| Female | 1 | 32 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 57 | |||||||||

| Male | 2 | 65 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 67 | 2 | 1 | 179 | ||||||||

| Age | 26.3±4.2 | 30.0±8.5 | 36.8±10.1 | 29.7±8.3 | 30.1±9.0 | 30.3±7.0 | 26±4.2 | 22±2.8 | 30.5±8.2¶ | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| 2002 13 | Total | 2 | 92 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 139 | |||||||

P<0.05 using an one-tail t-test to compare the mean age of the 2a group with that of the 1b, 3a, 3b, and 6a groups.

P<0.05 using an one-tail t-test to compare the mean age of the 1b group with that of the 3a, 3b, and 6a groups.

P<0.0001 using the ANOVA test to compare the mean ages of the following three groups: 393 patients, 136 IDUs, and 236 blood donors.

P<0.0001 using the ANOVA test to compare the mean ages of the following three subsets of 6a positive individuals: 67/393 patients, 70/136 IDUs, and 82/236 blood donors.

Phylogenetic analysis

Figure 1 shows two circular maximum likelihood (ML) trees reconstructed under the best fitting GTR+I+Γ model (Generalized time-reversible model with proportion of invariable sites and shape parameter of the gamma distribution) for the determined E1 (panel A) and NS5B (panel B) region sequences. With highly similar structures, they consistently show a great diversity of HCV, representing six genotypes, 12 subtypes, and two novel variants. Reasonably, 1b, 6a, 2a, 3a, and 3b account for the majority because they represent the major HCV strains in China.11-14 However, it is surprising that five rare subtypes are also detected: 1c, 2b, 2f, 4d, and 5a, in addition to two unclassified HCV-6 variants. As shown in both trees, isolates of the same subtypes are closely related and distinct from other lineages, and each cluster showed a significant bootstrap support.

Figure 2 shows two ML trees reconstructed with the E1 and NS5B sequences, respectively, for the 259 subtype 1b isolates. Both trees show largely similar structures, in which sequences of the same isolates were positioned consistently. Two major clusters, A and B, are shown, containing 66 and 154 sequences, respectively, representing 29.5% and 59.5% of the 259 1b isolates. They show bootstrap supports of 88% and 86% in the E1 tree, but not in NS5B. As described previously, cluster A is prevalent nationwide and B more common in Guangdong province.13 The latter is again verified.

Figure 2.

ML trees reconstructed for the 259 subtype 1b isolates using (A) E1 and (B) NS5B sequences. The 1a sequence M62321 is used as an outlier group. In each tree, two rectangles highlight the classification of A and B clusters. The scale bar at the bottom of each tree represents 0.02 nucleotide substitutions per site.

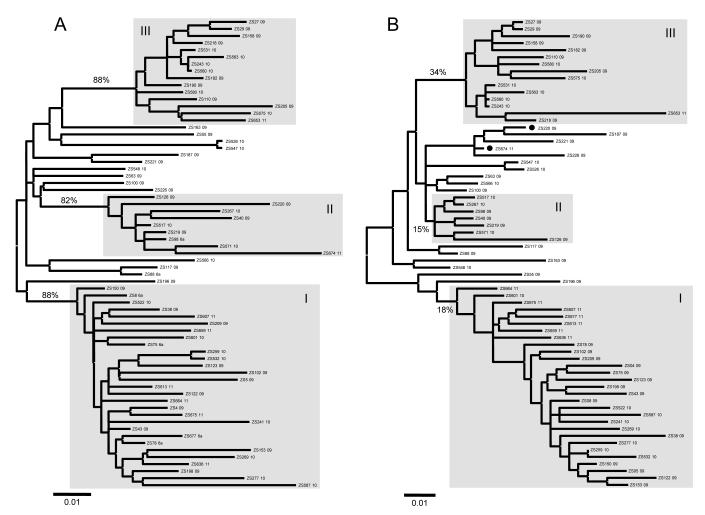

Figure 3 shows two ML trees reconstructed with the E1 and NS5B sequences, respectively, for the 67 subtype 6a isolates. Largely similar structures are presented in both trees and three previously defined clusters, I, II, and III, are maintained.12 They contain 29, 9, and 15 sequences, respectively, representing 43.3%, 13.4%, and 22.4% of the 6a isolates. They show bootstrap supports of 88%, 82%, and 88% in the E1 tree, but these are reduced to 18%, 15%, and 34% in the NS5B. Two isolates, ZS220 and ZS674 (black circles), show inconsistent groupings. They group into cluster II in the E1 tree but not in the NS5B.

Figure 3.

ML trees reconstructed for the 67 subtype 6a isolates using (A) E1 and (B) NS5B sequences. In each tree, three rectangles highlight the classification of I, II, and III clusters. The 6b sequence D84262 was initially used as an outlier group. However, it was removed from the figure after the 6a sequences were rooted.

Figure 4 shows two ML trees reconstructed with the E1 and NS5B sequences for the remaining 67 isolates. These include 29 isolates of 2a, 14 of 3a, 13 of 3b, three of 6e, and one each of 1a, 1c, 2b, 2f, 4d, and 5a, in addition to two novel HCV-6 variants. In the tree, different genotypes and subtypes are distinct, related lineages are in proximity, and isolates of the same subtypes form consistent monophyletic clusters each showing a significant bootstrap support.

Figure 4.

ML trees reconstructed for the 67 isolates of other HCV genotypes/subtypes using (A) E1 and (B) NS5B region sequences. Subtype designations are given at the internal nodes and bootstrap supports were shown in percentages.

Statistical analyses of mean ages

To determine if the HCV genotype distribution is correlated with the patients’ age (at the sampling date), we divided the 393 HCV-infected patients into groups according to their detected HCV subtypes. Five groups, 1b, 2a, 3a, 3b, and 6a, were classified. They contained 259, 29, 14, 13, and 67 patients, respectively, with mean ages of 43.9±18.1, 50.9±16.7, 38.0±11.5, 39.0±7.2, and 37.2±11.1 (Table 1). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of mean ages gave an F-value of 4.45 and p-value of 0.0016, indicating significant differences. Because people at different ages tend to behave differently, dissimilar epidemic behaviors are implied for HCV subtypes. To compare the 2a group with the 1b, 3a, 3b, and 6a groups, one-tail t-test of the mean ages was performed, which gave p values of 0.023, 0.003, 0.002, and 0.0002, respectively. A similar t-test was also conducted for comparing the 1b with the 3a, 3b, and 6a groups, which gave p values of 0.0445, 0.0222, and 9.314E-05. Collectively, these results indicate that the 2a and 1b groups were statistically older than other groups. It is likely that patients in the 1b and 2a groups had acquired HCV infections at earlier ages than those in the 3a, 3b, and 6a groups.

Recently, we have reported HCV prevalence among 236 volunteer blood donors (mean ages=30.5±8.2) and 136 IDUs (mean ages=34.7±7.2).11,12 Among them, 6a has been detected in 34.8% and 51.5%, respectively, and both are significantly higher than 17.1% for 6a in this study (P<0.05). To determine if the 393 patients were statistically older than the 236 donors and 136 IDUs, the ANOVA test of mean ages was also conducted. It gave an F-value of 3.01 and p-value of 1.83869E-29, robustly confirming the differences. A conclusion can be made that younger people tend to have higher frequencies of 6a. The ANOVA test of mean ages was also performed on the fractions of 6a-infected individuals: 67 of the 393 patients, 82 of the 236 donors, and 70 of the 136 IDUs (see Table 1). This gave an F-value of 12.04 and p-value of 1.11E-05 and indicates that the patients are statistically older than the donors who are older than the IDUs.

DISCUSSION

Both E1 and NS5B sequences of HCV were determined among 393 patients with chronic liver disease. This revealed 1b, 6a, 2a, 3a, and 3b accounting for 65.9%, 17.1%, 7.4%, 3.6%, and 3.3%, respectively, followed by 6e in 0.76% and 1a in 0.25%. Such a pattern is largely consistent with that we reported in 2002.13 However, compared to our recent data based on 236 volunteer blood donors and 136 IDUs that were also sampled in Guangdong province, a significantly (P<0.005) lower 6a percentage was revealed.11,12 Two statistical analyses helped for explanation: (1) among the 393 patients, those with 1b were predominant (65.9%) and significantly (P<0.05) older than those with 6a; (2) entirely or for 6a only, patients were significantly (P<0.0001) older than donors and IDUs (Table 1). Jointly, these results indicate that older individuals tend to have a higher proportion of 1b and lower 6a than younger ones. This is consistent with the results from recent studies that the worldwide 1b transmission is largely due to the contaminated blood transfusion and unsafe medical practice that were common before the virus was discovered in 1989.6,8 In contrast, the prevalence of 6a in China is mainly due to the IDU-linked transmission that reappeared in the relatively recent and mostly among young adults.11

A great diversity of HCV isolates was detected representing six genotypes, 12 subtypes, and two novel genotype 6 variants. This could be the first to show such a high complexity of HCV taxonomic lineages in China. Remarkably, the 1b predominance followed by 6a, 2a, 3a, 3b, 6e, and 1a is a feature of the HCV epidemic in Guangdong province.13 However, it is surprising that five rare subtypes, 1c, 2b, 2f, 4d, and 5a, were also detected. In a past study, we detected a 2f isolate, gz99799, from a patient who was also sampled in that hospital. 13 Searching the Los Alamos HCV database, we found that 1c and 2f are more frequently found in Indonesia than anywhere else.15-18 We therefore speculated that the 1c and 2f here we detected may also have their origins in Indonesia. This can be supported by the fact that in recent decades Chinese Indonesians have visited China more often than they had before. Among them many identify their ancestries in Guangdong province. It is likely that they visited their relatives and also traveled for medical services. Epidemiologically, 4d has never been detected in East Asia but it is prevalent in Europe; 5a is endemic in South Africa, sometimes detected in Europe, and occasionally in India (Genbank #: HQ393952) and Japan (Genbank #: D16738, D16791-5). In contrast, 2b is common in Japan and also detectable in Hong Kong and Taiwan.19-29 In this study, a 4d isolate was from a European visitor and a novel HCV-6 variant from an overseas Chinese living in Myanmar. However, the origin of the 5a isolate is intriguing because it was from a 52- year-old native man. Two possibilities exist: either he has journeyed to Africa or acquired the infection through contact with Africans living in Guangdong province. The latter seems to be more probable because an estimated 200,000-300,000 Africans are currently living this province (http://world.huanqiu.com/zhuanti/2010-08/1011039.html) who may have introduced 5a to the local people. With the data above, we conclude that an increased diversity of HCV isolates were detected in southern China. Although not native, some of them have been introduced to Guangdong province with a recent trend of it becoming a “World Production Center”. It has therefore attracted millions of visitors from around the world and an even greater number of migrant laborers across China, particularly from the remote and poor rural areas, to work in the myriad of factories in the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province.12 This has now caused a serious problem to public health there and is changing the HCV spectrum in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and specimens

Serum samples were obtained from routine testing for HCV-RNA performed from Aug 2009 - Dec 2011 on patients with chronic liver disease who visited the Department of Infectious Disease, 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong province, China. Only those samples positive for HCV-RNA were reserved, while those negative were excluded. Routinely, a simple blood test is used to screen the patients for chronic liver disease. It refers to that during the past six months or for a longer period ALT (alanine aminotransferase) elevation (>30 U/l) in serum is repeatedly or persistently tested.

Sequence amplification and phylogenetic analysis

E1 and NS5B sequences of HCV were amplified and sequenced using the approaches we recently described.12,13 To avoid possible carryover contaminations, standard procedures were taken.30 The resulting sequences were then analyzed using the BioEdit software.31 Prior to tree construction, the best-fitting substitution model was selected using jModeltest based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).32 Consistent with our recent results, GTR+I+Γ was found to be the best for all datasets.11 Under this model, ML trees were heuristically searched by SPR and NNI perturbation algorithms implemented in PHYML.33 With the tree files generated, ML tree topology was displayed using the MEGA5 program.34

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was supported by a grant from NIAID/NIH (5 R01 AI080734-03A).

Footnotes

Genbank accession numbersThe Genbank numbers of the HCV sequences are JX676774-JX677559.

Competing Interest: No.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethical Approval: The ethical review committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University had approved this study. Guidelines set by this committee were strictly followed. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients when they visited doctors in that hospital.

REFERENCE

- 1.Simmonds P, Bukh J, Combet C, Deleage G, Enomoto N, et al. Consensus proposals for a unified system of nomenclature of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2005;42:962–973. doi: 10.1002/hep.20819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pham VH, Nguyen HD, Ho PT, Banh DV, Pham HL, et al. Very high prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 variants in southern Vietnam: large-scale survey based on sequence determination. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64:537–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McOmish F, Yap PL, Dow BC, Follett EA, Seed C, et al. Geographical distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in blood donors: an international collaborative survey. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:884–892. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.884-892.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pybus OG, Barnes E, Taggart R, Lemey P, Markov PV, et al. Genetic history of hepatitis C virus in East Asia. J Virol. 2009;83:1071–1082. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01501-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmonds P. Genetic diversity and evolution of hepatitis C virus--15 years on. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3173–3188. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pybus OG, Charleston MA, Gupta S, Rambaut A, Holmes EC, et al. The epidemic behavior of the hepatitis C virus. Science. 2001;292:2323–2325. doi: 10.1126/science.1058321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pybus OG, Cochrane A, Holmes EC, Simmonds P. The hepatitis C virus epidemic among injecting drug users. Infect Genet Evol. 2005;5:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka Y, Hanada K, Mizokami M, Yeo AE, Shih JW, et al. A comparison of the molecular clock of hepatitis C virus in the United States and Japan predicts that hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the United States will increase over the next two decades. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15584–15589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242608099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goedert JJ, Chen BE, Preiss L, Aledort LM, Rosenberg PS. Reconstruction of the hepatitis C virus epidemic in the US hemophilia population, 1940-1990. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1443–1453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Hutin YJ. The global burden of disease attributable to contaminated injections given in health care settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:7–16. doi: 10.1258/095646204322637182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, Qin W, Cao H, Xu R, Tan Y, et al. HCV 6a prevalence in Guangdong province had the origin from Vietnam and recent dissemination to other regions of China: phylogeographic analyses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Wang Y, Xia W, Pybus OG, Qin W, et al. New trends of HCV infection in China revealed by genetic analysis of viral sequences determined from first-time volunteer blood donors. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu L, Nakano T, He Y, Fu Y, Hagedorn CH, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotype distribution in China: predominance of closely related subtype 1b isolates and existence of new genotype 6 variants. J Med Virol. 2005;75:538–549. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Nagayama R, Tao QM, et al. Prevalence, genotypes, and an isolate (HC-C2) of hepatitis C virus in Chinese patients with liver disease. J Med Virol. 1993;40:254–260. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890400316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuiken C, Yusim K, Boykin L, Richardson R. The Los Alamos hepatitis C sequence database. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:379–384. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotta H, Handajani R, Lusida MI, Soemarto W, Doi H, et al. Subtype analysis of hepatitis C virus in Indonesia on the basis of NS5b region sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3049–3051. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3049-3051.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lusida MI, Nagano-Fujii M, Nidom CA, Soetjipto, Handajani R, et al. Correlation between mutations in the interferon sensitivity-determining region of NS5A protein and viral load of hepatitis C virus subtypes 1b, 1c, and 2a. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3858–3864. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.3858-3864.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokita H, Okamoto H, Iizuka H, Kishimoto J, Tsuda F, et al. Hepatitis C virus variants from Jakarta, Indonesia classifiable into novel genotypes in the second (2e and 2f), tenth (10a) and eleventh (11a) genetic groups. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 2):293–301. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argentini C, Dettori S, Villano U, Guadagnino V, Infantolino D, et al. Molecular characterisation of HCV genotype 4 isolates circulating in Italy. J Med Virol. 2000;62:84–90. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200009)62:1<84::aid-jmv13>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calado RA, Rocha MR, Parreira R, Piedade J, Venenno T, et al. Hepatitis C virus subtypes circulating among intravenous drug users in Lisbon, Portugal. J Med Virol. 2011;83:608–615. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantaloube JF, Biagini P, Attoui H, Gallian P, de Micco P, et al. Evolution of hepatitis C virus in blood donors and their respective recipients. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:441–446. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantaloube JF, Gallian P, Laperche S, Elghouzzi MH, Piquet Y, et al. Molecular characterization of genotype 2 and 4 hepatitis C virus isolates in French blood donors. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1732–1739. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bruijne J, Schinkel J, Prins M, Koekkoek SM, Aronson SJ, et al. Emergence of hepatitis C virus genotype 4: phylogenetic analysis reveals three distinct epidemiological profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3832–3838. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01146-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sentandreu V, Jimenez-Hernandez N, Torres-Puente M, Bracho MA, Valero A, et al. Evidence of recombination in intrapatient populations of hepatitis C virus. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbeeck J, Maes P, Lemey P, Pybus OG, Wollants E, et al. Investigating the origin and spread of hepatitis C virus genotype 5a. J Virol. 2006;80:4220–4226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4220-4226.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, et al. Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 11):2391–2399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanabe Y, Nagayama K, Enomoto N, Izumi N, Tazawa J, et al. Characteristic sequence changes of hepatitis C virus genotype 2b associated with sustained biochemical response to IFN therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bukh J, Purcell RH, Miller RH. Sequence analysis of the 5′ noncoding region of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4942–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang SY, Sheng WH, Lee CN, Sun HY, Kao CL, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV type 1 subtypes in Taiwan: outbreak of HIV type 1 CRF07_BC infection in intravenous drug users. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1055–1066. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tippmann HF. Analysis for free: comparing programs for sequence analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:82–87. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]