Abstract

Skin grafting in nasal reconstruction, long used by dermatologists, can provide superior results and can well be the “go to” procedure for nasal reconstruction. The upper two-thirds of the nose is composed of both flattened, featureless and often thin skin that is well recreated with defect-only full-thickness grafting. Skin grafting for the lower third of the nose has been practiced for years by dermatologists; over the last 4 to 5 years, it has been embraced by plastic surgeons. The patient and donor site selection is critical. Meticulous attention to graft selection, utilization of a no-touch technique during graft harvest and placement of surgical bolsters with through-and-through tacking sutures are essential to ensure 100% graft take and a successful aesthetic result.

Keywords: full-thickness skin graft, Mohs reconstruction, nasal defect

When used appropriately, the full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) makes for a simple and aesthetically acceptable reconstruction option for nasal defects. Defects of the nasal sidewall and dorsum are well suited for FTSG provided that conscientious skin matching and surgical technique are undertaken. Lower third nasal defects, long treated with FTSG in the dermatologist community, are being treated more frequently by FTSG in the plastic surgery community as well. A FTSG in nasal reconstruction represents a “tried and true” technique, and in the hands of a skilled surgeon can provide excellent and reliable results.

Once considered inferior by plastic surgeons, FTSG reconstruction is becoming widely accepted as a go-to technique for certain types of nasal soft tissue defects. A FTSG is well established for the treatment of dorsum and sidewall defects, but its usefulness for lower third defects is often underappreciated. Lower third defects, for instance complete alar or complete tip defects, have established algorithms that often call for nasolabial or forehead flap reconstruction.1 However, with disciplined patient selection and donor-site selection, a FTSG is gaining an increasing role in reconstruction of lower third nasal defects.2 With careful patient selection, FTSG is a robust reconstruction tool for nearly all regions of the nose.

History

Skin grafting is the oldest form of tissue reconstruction known. Texts documenting the use of skin grafts for soft tissue reconstruction date back 2500 years. The first known description was found in India, in which a skin graft was used to reconstruct an amputated nose.3 Modernization of the technique started to come about in the 19th century, with descriptions of the pinch graft in 1869 and the FTSG in 1875.4,5 The persistence of this technique over time illustrates its utility and strength as a tried and true reconstruction technique.

Physiology of a Skin Graft

A skin graft is unique from other forms of nasal reconstruction, in that it does not have its own blood supply. Instead, a skin graft must recruit blood supply from the surrounding tissues at the recipient site. There are several stages involved in this process.6

The first stage of graft revascularization, plasmatic imbibition, begins with the deposition of fibrin and granulation tissue to the underlying tissues. The graft absorbs nutrients during this stage, adding significant water weight that helps maintain vascular patency and keeps the graft moist.6,7,8 After this stage, the graft is firmly secured to the underlying recipient site. After 48 hours, inosculation occurs as graft vessels and recipient vessels form connections through angiogenesis and the anastomosis of existing vessels.9,10,11 Although complete return of sensation over the grafted area is never fully achieved, partial sensation usually returns after several months.

The bridging phenomenon allows a skin graft to be used to cover a relatively avascular surface. As long as a portion of the defect is well vascularized, a skin graft can recruit vessels from this area to supply blood vessels to the graft overlying the avascular recipient site.10

Anatomical Considerations

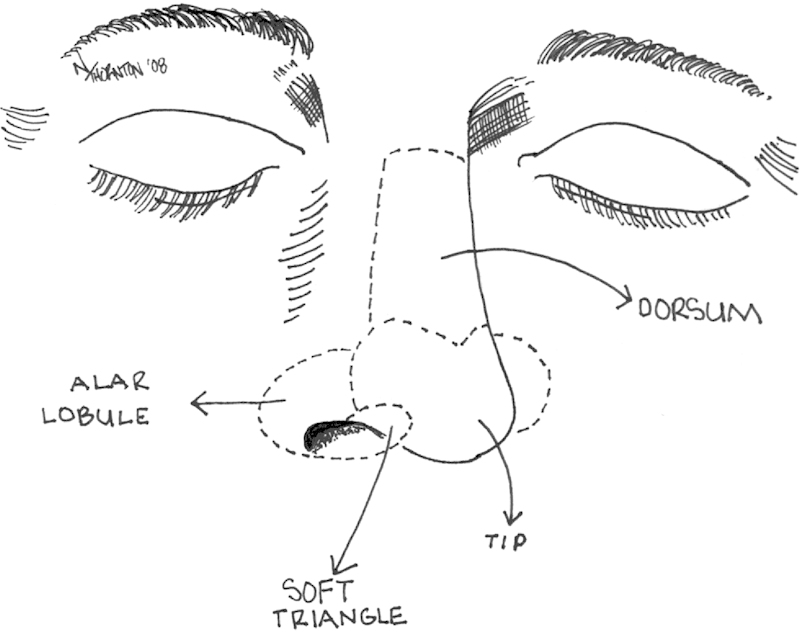

Differing nasal subunits, interlaced convexities and concavities, as well as varying skin thicknesses make the nose one of the most complex aesthetic units of the face. The upper two-thirds of the nose are composed primarily of flat, featureless, and, especially in the elderly population, thin skin. The skin of the upper two-thirds demonstrates significantly more laxity as compared with the skin of the lower third. The lower third of the nose has a significantly more complex contour than the upper two-thirds of the nose. The lower third of the nose is defined by the alar rims inferiorly, the nasolabial grooves laterally, and the alar groove, which forms the junction with the upper two-thirds of the nose.2,12,13 Particular attention must be paid to the nasolabial grooves and the alar rims, as any distortion of these margins is clearly evident and nearly impossible to correct. Six subunits comprise the lower third: the bilateral ala, the soft triangles, the central tip, and the columella (Fig. 1).14 The surgeon need not be dogmatic about applying the subunit principle versus defect-only reconstruction for repair of nasal defects. Restoration of the various contours of the nose is the key to aesthetic nasal reconstruction.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of nasal subunits.

The characteristics of the nasal skin are important to consider prior to nasal soft tissue reconstruction. The skin of the lower third is thick and composed of sebaceous glands, unlike the thin skin of the upper two-thirds.15 This inherent thickness makes it difficult to rotate a local flap into position, making skin grafting with proper donor site selection an excellent reconstructive option. Skin from the forehead donor site offers a thick skin capable of providing a more consistent result with less contour irregularity in lower third defects. As a rule of thumb, the donor site should have similar skin thickness and sun exposure as the recipient site for FTSG.

Preoperative Assessment

Proper patient and donor-site selection is essential to achieving optimal reconstructive results. Criteria for selecting nasal defects that can be appropriately treated with FTSGs include defect location; a small defect measuring less than 1 cm in diameter on the lower third, the entire dorsum, the entire sidewall; and a partial-thickness defect with underlying dermis, subcutaneous tissue, or perichondrium. Larger and deeper defects are more appropriately reconstructed using local and adjacent flaps. Adhering to the concept of like replacing like, the appropriate donor site should be selected based on texture, thickness, color, and sun exposure.

Surgical Technique

The procedure can be performed using local anesthesia, with or without intravenous sedation. The operative approach begins with reverticalization of the wound edges with a double-edged beaver blade and careful debridement of any nonviable tissue in the base of the defect. Normalizing any contour abnormalities will facilitate graft take at the recipient site. This portion is performed under loupe magnification. When feasible, the excisions are taken to the borders of the nasal subunits, but strict adherence to the subunit principle is unnecessary and one should think of this as a defect-only reconstruction.

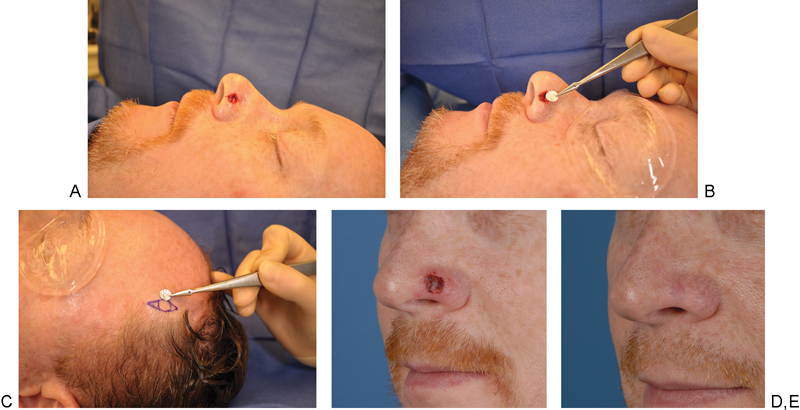

Following debridement, a skin graft is designed to match the exact size of the nasal defect. Although there is debate, it is our preference to design a FTSG to match the defect exactly in all dimensions. We do not design the skin graft to be larger than the defect, as we feel that a graft inset under slight tension will improve graft take. To design the FTSG, a foil pattern template of the defect is created. The template is a three-dimensional construct, taking into account contour, depth, and size. This accounts for the relative concavity and convexity of the surrounding tissue. The donor-site markings are extended beyond the template to form an ellipse to remove dog ears from the donor-site incision (Fig. 2). By using the foil pattern template and sharply scoring the graft within the ellipse of the donor site, ensures an accurately sized FTSG. The donor site for the skin graft depends largely on the location of the defect. For upper two-thirds defects, thin skin from the preauricular region or neck works well. For lower third defects, the thick skin of the forehead provides the best match. For all donor sites, take care to avoid any hair-bearing areas, as hair can be difficult to remove and can ruin a good reconstruction. Once harvested, take care to handle the tissue in an atraumatic fashion, or “no-touch harvest,” for the duration of the procedure. The skin graft can be precisely sewn in using continuous 5-0 fast-absorbing gut sutures running in opposite directions and tied at the opposite ends (Fig. 3). It is our experience that chromic gut sutures result in an inappropriate inflammatory response, thus fast-absorbing plain gut sutures should be used. This technique provides a stable inset without bunching or graft distortion.

Fig. 2.

(A) Primary defect of the left ala. (B) A foil pattern template was designed the exact size of the defect and to account for the contour of the surrounding tissue (C). Using the foil pattern template and sharply scoring the graft within the ellipse of the donor site prior to harvest, graft distortion is avoided (D). 1-week postoperative results. (E) 10-months postoperative results.

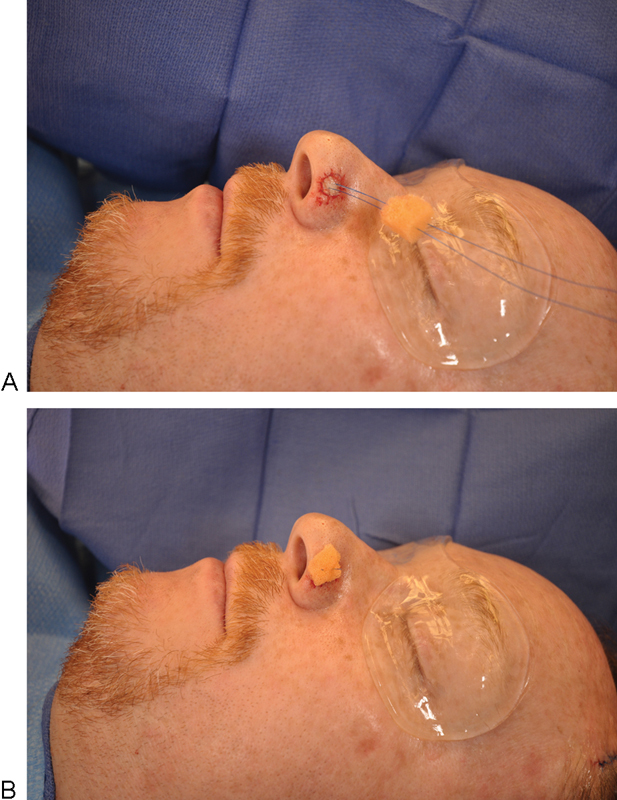

Fig. 3.

Continuous 5-0 plain gut sutures are used to inset the graft. Four-corner bolster sutures are used to secure the bolster.

Contact between the graft dermis and the recipient bed is critical for inosculation. Therefore, careful defatting of the graft and the use of a bolster are indispensable to ensuring survival of the FTSG. A surgical prep sponge coated only with antibiotic ointment can be used for the bolster. The sponge is both compressible and sterile, thus providing sufficient support and rebound. Double armed 3-0 Prolene (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) sutures are placed through the center of both the underlying tissue and the graft. The through-and-through 3-0 Prolene sutures are then passed through the bolster and tied in place (Fig. 4). Use of the bolster obliterates any remaining central dead space and helps ensure adequate contact between the recipient bed and the graft. 5-0 silk sutures are then placed through the native skin edge, the graft, and the bolster at four points around the graft. The donor site and bolster are coated with antibiotic ointment.

Fig. 4.

(A) A surgical prep sponge coated with antibiotic ointment inset with 3-0 Prolene sutures through the bolster to provide a sterile and compressible material. (B) Obliteration of the dead space between the graft and recipient bed.

Postoperative care should begin immediately with local wound care. Written instructions are helpful to ensure patient compliance. Patients are instructed to begin showering on the second postoperative day with generous application of antibiotic ointment to the bolster before and after showering. Weekly office visits are recommended until full graft survival has been confirmed. Topical scar therapy creams and silicon sheeting may be offered to patients once graft survival is ensured. At ∼6 weeks postgrafting, based on the characteristics and appearance of the scar, dermabrasion can be performed to improve both the graft color and to diminish the patchy appearance of the graft. Up to three dermabrasion sessions, at 6-week intervals, may be performed. Primary dermabrasion is not typically performed due to the unpredictable healing and risk of trauma to the delicate graft. Although some authors have advocated dermabrasion of the entire nasal subunit, this is largely unnecessary.16 In our experience, dermabrasion can be confined to the graft and the immediate surrounding areas only. Simple wound closure should not be considered the end point in healthy patients, additionally aesthetic standards should be met based on normal appearance, contour, and color match (Figs. 5678).17

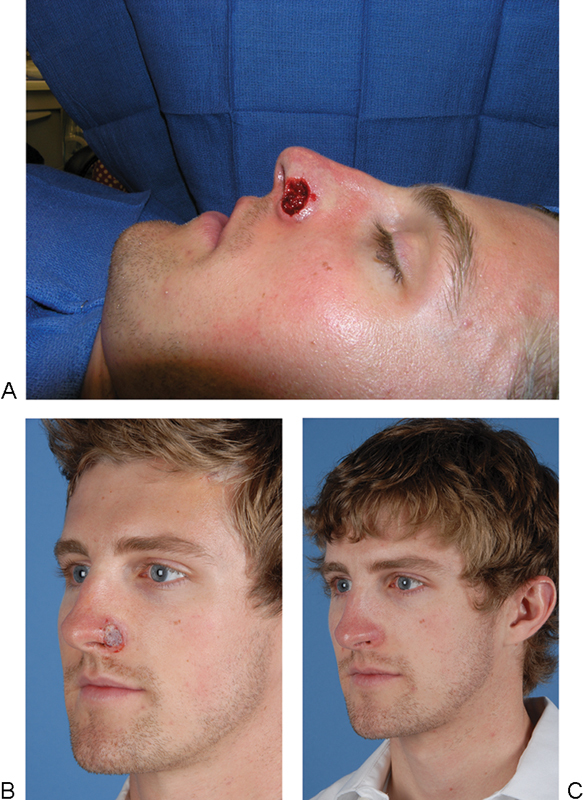

Fig. 5.

(A) Preoperative defect of the nasal ala. (B) 7-days post inset of a full-thickness skin graft. (C) 9-months post inset of a full-thickness skin graft.

Fig. 6.

(A) Preoperative tip defect. (B) Inset of a full-thickness skin graft. (C) 6-month postoperative results.

Fig. 7.

(A) Sidewall nasal defect. (B) 1-month post inset full-thickness skin graft. (C) 6-months post inset full-thickness skin graft.

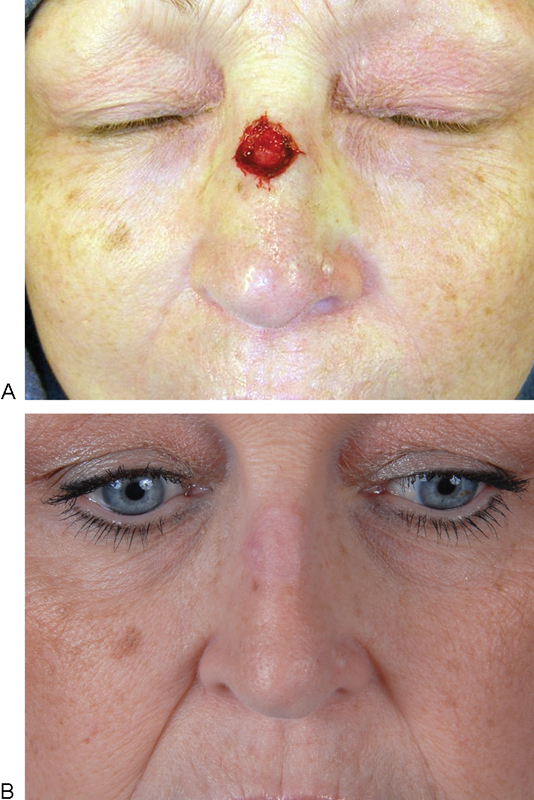

Fig. 8.

(A) Nasal dorsum defect. (B) 10-months post inset full-thickness skin graft.

Technical Pearls

Small defects of the lower third, especially those 1 cm and smaller in diameter, can be more difficult to reconstruct with local or adjacent flaps. Unpredictable pincushioning, distortion of the aesthetic subunit, or even worsening of the principle defect are all possible complications of using local flaps. Small, shallow defects, such as those arising from neoplasm excision by Mohs micrographic surgery, often have superior results when using a FTSG.

The preauricular region is our donor site of choice for smaller defects on the upper two-thirds of the nose. In our experience, the preauricular skin is a better color match compared with postauricular or supraclavicular skin. This skin experiences similar sun exposure as the upper two-thirds of the nose and shares similar skin thickness. Harvesting the graft is much easier and better tolerated in a mildly sedated patient.

On the other hand, for defects of the lower third, forehead skin provides a thicker, relatively sebaceous skin with oily texture that has the same degree of sun exposure and actinic damage as the lower third of the nose. These qualities render it a superior donor site for defects of the lower third of the nose. The lateral forehead is an ideal location to harvest the graft because the scar can be hidden in the junction of the hair-bearing and nonhair-bearing scalp. Both the preauricular and forehead donor site grafts should be designed along relaxed skin tension lines and in areas of nonhair-bearing skin.

We feel that meticulous attention to atraumatic handling of the graft is essential to ensure 100% graft take. To this end, we utilize a no-touch harvest technique, as well as careful placement of surgical bolsters with through and through tacking sutures. In addition, we do not fenestrate the skin graft as this would damage the delicate graft and does not improve graft take.

Complications

One concern with using FTSGs is the potential for color mismatch and contour irregularity, which will yield a patch-like appearance. Contour irregularities can occur if the surgeon does not take into account FTSG contraction. After excision, FTSG's contract primarily ∼10 to 15%. Instead of harvesting a larger graft to correct for primary contraction, this problem can be controlled for by insetting the graft under appropriate tension.

The use of FTSG around the alar rim can result in unacceptable alar notching. In these cases, attention to proper patient selection is paramount. Male patients with very thick, sebaceous skin have a decreased risk of alar retraction after skin grafting and thus can be skin grafted safely. A FTSG should not be used for deep defects and those adjacent to the alar rim.

As with any graft, full or partial graft loss is always possible. Although complications are reduced by prudent defatting and bolster placement, other comorbidities such as smoking, obesity, and diabetes necessarily factor into graft survival. Smokers, in particular, are at increased risk of graft loss secondary to the vasoconstrictive properties of nicotine.

Discussion

Although dermatologists have been routinely using FTSGs to cover small, superficial defects of the nose, only recently has this technique been adopted by plastic surgeons. Skin grafting was not considered a good option for the reconstruction of nasal defects, especially those of the lower third. Inappropriate placement of large, poorly matched supraclavicular or postauricular skin grafts often yielded results that were aesthetically inferior necessitating revisionary surgery. Inappropriate donor site and defect selection led to poor results, and steered many reconstructive surgeons away from these techniques.

However, skin grafting can provide well contoured and aesthetically acceptable results, provided that the defect and patient are thoroughly assessed preoperatively. The size and extent of the defect must be accurately ascertained. Defects larger than 1 cm in diameter are better treated with alternative reconstructions for lower-third reconstruction. Superficial defects up to 2 cm in the sidewall or dorsum can be repaired using FTSGs. Similarly, defects necessitating cartilage grafting are considered complex nasal defects and skin grafting is not indicated for these patients. Operative technique, including designing the graft as an exact match of the defect and bolstering the graft with a surgical sponge, enhances a surgeon's results when using a FTSG.

Notably, FTSGs can be much less predictable than nasolabial or local flaps. The healing period can involve significant color and texture changes prior to arriving at the final result. The skin graft will initially appear white and pale when it is ischemic, and then darken later as it revascularizes. In some patients, especially those with a thick graft, the graft may shed its epidermis, giving the physician and patient the impression of graft failure. The patient needs to be counseled preoperatively for this possibility and reassured during their frequent postoperative visits. The color and contour changes vary unpredictably during the healing process; however, with appropriate postoperative scar care and dermabrasion the end result should be satisfying for both the patient and the physician. Ultimately, utilizing meticulous patient selection and defect analysis, a surgeon will get the best outcomes for their patients, irrespective of the reconstructive method.

Conclusion

Skin grafting in nasal reconstruction can deliver superior aesthetic results and could become a go-to reconstructive procedure for small, shallow defects of the nasal region. A FTSG can be a technically simple operation relative to local and adjacent flaps, and yield similar, if not superior, results with careful patient selection and preoperative wound examination.

References

- 1.Hill T G. Contouring of donor skin in full-thickness skin grafting. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13(8):883–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1987.tb00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCluskey P D, Constantine F C, Thornton J F. Lower third nasal reconstruction: when is skin grafting an appropriate option? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):826–835. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b03749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauben D J, Baruchin A, Mahler A. On the histroy of the free skin graft. Ann Plast Surg. 1982;9(3):242–245. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis J S. The story of plastic surgery. Ann Surg. 1941;113(5):641–656. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194105000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady J G, Grande D J, Katz A E. The purse-string suture in facial reconstruction. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18(9):812–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratner D. Skin grafting. From here to there. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16(1):75–90. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Converse J M, Smahel J, Ballantyne D L Jr, Harper A D. Inosculation of vessels of skin graft and host bed: a fortuitous encounter. Br J Plast Surg. 1975;28(4):274–282. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(75)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Converse J M, Uhlschmid G K, Ballantyne D L Jr. “Plasmatic circulation” in skin grafts. The phase of serum imbibition. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43(5):495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry L, Marshall D C, Friedman E A, Goldstein D P, Dammin G J. A histologic study of the human skin autograft. Am J Pathol. 1961;39:317–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smahel J. The healing of skin grafts. Clin Plast Surg. 1977;4(3):409–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarem H A, Zweifach B W, McGehee J M. Development of microcirculation in full thickness autogenous skin grafts in mice. Am J Physiol. 1967;212(5):1081–1085. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.5.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins P S, Farber G A. Postsurgical dermabrasion of the nose. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10(6):476–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1984.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leibovitch I, Huilgol S C, Richards S, Paver R, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database: short-term recipient-site complications in full-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(11):1364–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker S, Swanson N A. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michelson L N, Peck G C Jr, Kuo H R. et al. The quantification and distribution of nasal sebaceous glands using image analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20(4):303–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00228460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams D C, Ramsey M L. Grafts in dermatologic surgery: review and update on full- and split-thickness skin grafts, free cartilage grafts, and composite grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(8 Pt 2):1055–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohrich R J Griffin J R Ansari M Beran S J Potter J K Nasal reconstruction—beyond aesthetic subunits: a 15-year review of 1334 cases Plast Reconstr Surg 200411461405–1416., discussion 1417-1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]