Abstract

A gene encoding a putative carboxyl-terminal protease (CtpA), an unusual type of protease, is present in the Borrelia burgdorferi B31 genome. The B. burgdorferi CtpA amino acid sequence exhibits similarities to the sequences of the CtpA enzymes of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and higher plants and also exhibits similarities to the sequences of putative CtpA proteins in other bacterial species. Here, we studied the effect of ctpA gene inactivation on the B. burgdorferi protein expression profile. Total B. burgdorferi proteins were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and the results revealed that six proteins of the wild type were not detected in the ctpA mutant and that nine proteins observed in the ctpA mutant were undetectable in the wild type. Immunoblot analysis showed that the integral outer membrane protein P13 was larger and had a more acidic pI in the ctpA mutant, which is consistent with the theoretical change in pI for P13 not processed at the carboxyl terminus. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—time of flight data indicated that in addition to P13, the BB0323 protein may serve as a substrate for carboxyl-terminal processing by CtpA. Complementation analysis of the ctpA mutant provided strong evidence that the observed effect on proteins depended on inactivation of the ctpA gene alone. We show that CtpA in B. burgdorferi is involved in the processing of proteins such as P13 and BB0323 and that inactivation of ctpA has a pleiotropic effect on borrelial protein synthesis. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of both a CtpA protease and different substrate proteins in a pathogenic bacterium.

The etiologic agent of Lyme borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, is transmitted by infected Ixodes ticks (11, 56). The early symptoms of the disease are flu-like and, if left untreated, may develop into systemic disease with arthritic, cardiac, and neurological manifestations (55). Since all borrelial species are host-propagated bacteria that shuttle between a vertebrate and an arthropod host, these spirochetes have developed strategies to sense and survive in these environments (50). The adaptations involve altered levels of gene expression in response to changes in temperature, pH, salts, and other host-dependent factors (1, 12-14, 17, 42, 51, 57, 62).

There is limited knowledge about protein processing and protein modification in B. burgdorferi. A homologue of genes encoding carboxyl-terminal proteases (Ctp), designated ctpA (The Institute for Genome Research genome database designation bb0359), is present on the B. burgdorferi B31 MI chromosome (20, 40). CtpA proteases belong to a group of proteases that were initially identified by genetic complementation analysis of specific photosynthetic mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (3, 52). Based on site-directed mutagenesis of the catalytic center of the enzyme (27) and the finding that the proteolytic activity is resistant to any conventional protease inhibitor (60, 61), CtpA is classified as an unusual type of serine-like protease. A CtpA protease has also been identified in Bartonella bacilliformis, but no target for this enzyme has been identified yet. This B. bacilliformis protease shows autocatalytic activity as 16 amino acids are removed from the CtpA carboxyl terminus (36). CtpA proteases have also been identified in chloroplasts of algae and higher plants (28, 60).

Overall, carboxyl (C)-terminal processing in prokaryotes is not well understood. However, a number of proteins in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells are synthesized in a precursor form with cleavable C-terminal extensions (21, 23, 25, 29, 35, 46, 53). C-terminal processing of precursor proteins destined for export to the periplasm or transported into organelles has been reported in some cases (16, 37). Also, a number of surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria are anchored to the cell wall envelope by a transpeptidation mechanism that requires a C-terminal sorting signal, which is cleaved off by the sortase enzyme (34).

In previous studies, a 13-kDa integral outer membrane protein, P13, of B. burgdorferi was analyzed, and it was found that this protein is processed at both ends (38, 40). The P13 protein is processed at the amino (N) terminus, where the first 19 amino acids are cleaved off, most likely by signal peptidase I, and at the C terminus by removal of 28 amino acids (38, 40). The P13 protein was further found to function as a channel-forming protein in lipid bilayer experiments (43).

This investigation was performed with the aim of determining if the putative CtpA protein functions as a C-terminal processing protease in B. burgdorferi. We inactivated the ctpA gene in B. burgdorferi by allelic exchange (9, 59) and demonstrated that a number of proteins showed an altered expression pattern in the ctpA mutant. The P13 protein was larger in the ctpA mutant, indicating that P13 is a substrate for the C-terminal processing protease CtpA in B. burgdorferi. Additionally, the synthesis of BB0323 and Oms28 was different in the ctpA mutant than in wild-type cells. Complementation of the ctpA mutant restored protein synthesis compatible with the wild-type phenotype. In the present study, we also compared the B. burgdorferi CtpA enzyme to similar putative CtpA proteins encoded in a number of bacterial genomes that have been sequenced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. burgdorferi strains and growth conditions.

The Borrelia strains used in this study were B. burgdorferi B31, which was originally isolated from a tick collected on Shelter Island, N.Y (11), and B31-A, a high-passage noninfectious clone of B31 that was used for the gene inactivation experiment (9). Bacteria were grown in BSK-II (4) or BSK-H (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), both supplemented with 6% rabbit serum, at 34 or 35°C. Single colonies of B. burgdorferi were obtained as described elsewhere (45).

Sequence analysis and structure predictions.

The amino acid sequence was searched for homologies by using protein PSI-BLAST at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) or was analyzed for conserved domains by using the Conserved Domain Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) (2). The theoretical mass and pI were calculated by using the ExPASy Molecular Biology Server (http://us.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html) (8). The secondary structure was predicted by using Jpred at EBI (http://jura.ebi.ac.uk:8888) (15). The presence of a signal sequence was analyzed at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP (26).

Construction of plasmid for inactivation of the ctpA gene.

Plasmid pCTP12 was constructed to inactivate the ctpA gene. By using primers ctp1 and ctp1rev (Table 1), a fragment covering 771 bp of the ctpA gene and an upstream region was amplified. The PCR fragment was ligated to pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, Wis.). By using an EcoRI site in the pGEM-T Easy vector and an XbaI site in primer ctp1rev, the cloned DNA fragment was excised and moved to an EcoRI- and XbaI-digested pUC18 vector. Primer ctp2 containing an XbaI site and primer ctp2rev (Table 1) were used to amplify 558 bp of the ctpA gene and downstream DNA, and the PCR fragment obtained was ligated to the first fragment by using the same procedure. A 1.3-kb PflaB-kanamycin fragment described elsewhere (9) was amplified with primers KNa1 and KNa1rev (43) and ligated into pGEM-T Easy. The kan fragment was then subcloned into the XbaI-digested ctpA gene in the pUC18 vector. To disrupt the bla gene conferring ampicillin resistance, the resulting plasmid was digested with BglI, treated with T4 polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) used according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then relegated and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The resulting E. coli clones were tested for carbenicillin sensitivity.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Application |

|---|---|---|

| ctp1 | ACAAGCAATACGCTTTTTCCTTC | Gene inactivation |

| ctp1rev | TCTAGATCCTCCGGTATTAAGCCTTAA | Gene inactivation, Southern blotting |

| ctp2 | TCTAGATAAGGCAAGCTCAAAACAAG | Gene inactivation |

| ctp2rev | AAAGCATCCTTCAGGACCTATTA | Gene inactivation |

| ctp1B | TGCATTCCCAAGATAAGCAAGA | Mutant analysis |

| ctp2D | TTAAAGAAATATATAATTACGGAG | Mutant analysis |

| ctp-pET3 | GTACATATGAATCCACACACCTCTG | Overexpression |

| ctp-pET2 | CTTCTCGAGTTAATTACCTAATTTAGAC | Overexpression |

| CTP-PstI | ATTTCTGCAGCCCTTAATTCTTTATC | Complementation |

| CTP-KpnI | AATAGGTACCTAAATTGGCCATGAAA | Complementation, Southern blotting |

Restriction sites are indicated by boldface type.

Construction of plasmid for genetic complementation.

The shuttle vector pBSV2G (18), containing a gentamicin resistance cassette, was used to construct plasmid pBSV2G+ctpA for genetic complementation. A region covering the ctpA gene and 261 bp upstream and 101 bp downstream of the gene was amplified with primers CTP-PstI and CTP-KpnI (Table 1), which contained PstI and KpnI restriction sites, respectively. The PCR product was purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.), subjected to restriction enzyme digestion, ligated into PstI- and KpnI-digested pBSV2G, and transformed into E. coli TOP10. Large-scale plasmid preparations were obtained by using Qiagen HiSpeed Maxipreps (Qiagen).

Electroporation of B. burgdorferi and screening of transformants.

Preparation of competent B. burgdorferi cells, electroporation, and plating of transformants were done as described previously (48, 59), and single colonies were obtained as described elsewhere (45). Briefly, for each transformation, 20 to 30 μg of plasmid DNA in 5 μl of water was used. After electroporation, the bacteria were resuspended in 5 ml of BSK-H and incubated overnight at 35°C. The transformed bacteria were plated on solid BSK-II containing kanamycin (200 μg/ml) or gentamicin (40 μg/ml). The plates was incubated at 35°C with 1% CO2 until colonies were visible. Antibiotic-resistant colonies were screened by PCR for allelic exchange at the ctpA locus or for the presence of the shuttle vector. Individual colonies were picked with sterile toothpicks and added to tubes containing a PCR mixture with primers 1 and 9 (kan5′+NdeI and pOK.7+NheI) as described elsewhere (9) to detect the kan gene, or primers 3-pCR2-5fgen+AvrII and 4-pCR2-3fgen-MluI were used to detect the aacC1 gene conferring gentamicin resistance (Gmr) (18). The PCR conditions were 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min. To obtain clonal mutants, individual colonies were aspirated with a sterile Pasteur pipette and grown in 5 ml of BSK-H containing kanamycin (200 μg/ml) or gentamicin (40 μg/ml). Primers ctp1B, ctp2D (Table 1), and KNaB (43) were used to further analyze a number of possible ctpA mutants. The PCR conditions were 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The resulting ctpA mutant was designated B31-A(ΔctpA); in this mutant nucleotides 772 to 867 of ctpA were deleted by insertion of the PflaB-kan resistance cassette.

Determination of plasmid profile and recovery of shuttle vector in E. coli.

Total DNA of B31-A (wild-type ctpA), B31-A(ΔctpA), B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G (ctpA mutant containing empty shuttle vector), and B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G+ctpA (ctpA mutant containing shuttle vector with the wild-type ctpA gene) were prepared by using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega). The plasmid contents of B. burgdorferi clones were determined by PCR as previously described (19). Total DNA was used for transformation of competent E. coli TOP10 in order to investigate the presence of the shuttle vector. Plasmids were prepared from E. coli transformants by using a mini plasmid purification kit (Qiagen) and were analyzed in a 0.8% agarose gel.

Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNA from wild-type and mutant borreliae were isolated as described above. Each DNA was digested with either EcoRV or PstI at 37°C for 20 h, separated by electrophoresis in a 0.7% agarose gel, and transferred overnight onto a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, England) by capillary force in 20× SSC (3 M sodium chloride plus 0.3 M sodium citrate). A DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions for labeling 1 μg of DNA probe, hybridizing DNA at 42°C for 18 h, and detecting a bound DNA probe. A PCR fragment obtained with primers KNa1 and KNa1rev (43) was used to detect the kan gene, a PCR fragment obtained with primers CTP-KpnI and ctp1rev (Table 1) was used to detect the ctpA gene, and DNA amplified by using primers 3-pCR2-5fgen+AvrII and 4-pCR2-3fgen-MluI (18) was used to identify the aacC1 gene in the shuttle vector. The PCR conditions were 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min.

Overexpression of CtpA for antiserum production.

For overproduction of B. burgdorferi CtpA in E. coli, the pET-28a(+) plasmid (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) was used. The C-terminal half of the CtpA protein (corresponding to nucleotides 672 to 1425) was amplified by PCR by using oligonucleotides ctp-pET3 and ctp-pET2 (Table 1). The Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche) was used for amplification with the following reaction conditions: 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min repeated five times; and 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min repeated 35 times. The 5′ oligonucleotide was modified to contain an NdeI site, and the 3′ oligonucleotide contained an XhoI site. After restriction enzyme digestion, the PCR product was ligated in frame with the pET-28a(+) plasmid-encoded N-terminal His tag and thrombin cleavage site. The reversed oligonucleotide was modified to contain a stop codon preventing fusion to the vector-encoded C-terminal His tag. E. coli TOP10 was transformed and screened for recombinant plasmid-containing cells. A plasmid from these cells with the correct insert was used for transformation of E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen), which was needed for overexpression of protein. E. coli cells carrying expression plasmids were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml. Growth was monitored by measuring the turbidity of the culture at 600 nm (A600). When the A600 reached 0.6, protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. The culture was incubated further for 2 h, and cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min. The cells were suspended in 0.1 culture volume of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Lysozyme (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, and the cells were disrupted by sonication. The soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The recombinant protein was expressed in inclusion bodies. Inclusion bodies were washed twice with 40 ml of wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) and used to raise antiserum against B. burgdorferi CtpA.

Antibodies.

Polyclonal antiserum was raised against recombinant truncated CtpA produced as described above. One milligram of washed inclusion bodies was separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)—12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel, and recombinant CtpA protein was excised from the gel and used for immunization. Approximately 100 μg of protein was used for immunization and boosting of a rabbit. Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 15G6 (47) and polyclonal antiserum directed against P13 were used as described previously (40). Polyclonal antiserum binding to Oms28 was described by Skare et al. (54).

Protease treatment, protein electrophoresis, and immunoblotting.

Cell surface proteolysis of intact Borrelia was conducted as previously described by Barbour et al. (5), with minor changes described by Noppa et al. (40). For one-dimensional gel electrophoresis, B. burgdorferi was grown to the late exponential phase and harvested by centrifugation, and total-protein extracts were prepared as described elsewhere (5, 6). Proteins were separated with a 10 to 20% Tricine polyacrylamide gradient gel, a 4 to 12% NuPAGE polyacrylamide gradient gel, or a 12% NuPAGE polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Two-dimensional nonequilibrium pH gradient gel electrophoresis (2D-NEPHGE) with a Hoefer SE600 gel apparatus was performed as described elsewhere (14). Briefly, total protein was prepared from B. burgdorferi spirochetes grown to a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and rinsed with cold 50 mM NaCl in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6). The cells were then resuspended in NEPHGE sample buffer (9 M urea, 4% Nonidet P-40, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% preblended ampholytes [Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden]) at a density of 2 × 107 cells/μl and incubated with agitation overnight at room temperature. Solubilized proteins were then separated from cell debris by ultracentrifugation (150,000 × g, 1 h, 24°C), and the samples were kept at −80°C until they were used. Proteins from approximately 2 × 108 or 4 × 108 cells were focused for a total of 2,400 to 2,500 V · h. Focused tube gels were extruded and equilibrated for 15 min in 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol-2.0% SDS-10% glycerol in 0.125 M Tris base. The proteins were separated in the second dimension by standard SDS—12.5% PAGE. Broad-range protein standards were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.

For detection, proteins were stained with a SilverQuest kit (Invitrogen) or a Silver Stain Plus kit (Bio-Rad). For immunoblot analysis of two-dimensional gels, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (pore size, 0.45 μm; Trans-Blot transfer medium; Bio-Rad) by using a Bio-Rad Trans Blot cell (30 mV, 12 h, 4°C). For immunoblot analysis of one-dimensional gels, proteins were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PALL Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.) by using a Bio-Rad Trans Blot cell (1.5 mA/cm2, 1.5 h, room temperature). The transferred proteins were probed with primary antibodies and were detected by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

MALDI-TOF analysis.

For matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—time of flight (MALDI-TOF) analysis, proteins were separated by 2D-NEPHGE and stained with silver, and spots were excised with a sterile scalpel. Protein spots were processed as follows. Each spot was rinsed twice with Milli-Q water (500 μl, 10 min), and silver ions were removed by addition of 15 mM potassium ferricyanate and 50 mM sodium thiosulfate to the gel slices (100 μl, 15 min). The gel slices were then rinsed twice in Milli-Q water (500 μl, 10 min) and three times in 50% acetonitrile (ACN) in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.9) (500 μl, 10 min), dehydrated in 100% ACN (500 μl, 10 min), and lyophilized under a speed vacuum for 30 min with low heat. Protein spots prepared in this manner were stored at −20°C until in situ digestion.

For in situ digestion, each gel slice was rehydrated in 20 to 30 μl of a solution containing 20 μg of sequencing-grade trypsin (Sigma) per ml in 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.9) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Peptides were extracted from the gel slices by two washes with 50 μl of 50% ACN-5.0% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in Milli-Q water (37°C, 15 min), followed by a final extraction with 100% ACN (37°C, 15 min). The extracts were combined, and the peptides were lyophilized with a speed vacuum and stored at −20°C until they were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. To prepare samples for MALDI-TOF analysis, lyophilized peptides were suspended in 4 μl of 50% ACN in 0.1% TFA, mixed with an equal volume of a solution containing 10.0 mg of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Aldrich) per ml in 50% ACN in 0.15% TFA, and crystallized on stainless steel MALDI plates by using the dry-drop method. The mass of each extracted peptide was determined with a Voyager STR MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (PE Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) used in the positive reflector mode; trypsin mass peaks were used as internal calibration standards. OspA excised from the 2D-NEPHGE gel was used as a positive control. Protein Prospector (University of California, San Francisco, Mass Spectrometry Facility; http://prospector.ucsf.edu) was used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information database for B. burgdorferi proteins that matched the empirically derived peptide mass fingerprint for each unknown protein spot.

RESULTS

Identification and sequence analysis of B. burgdorferi CtpA.

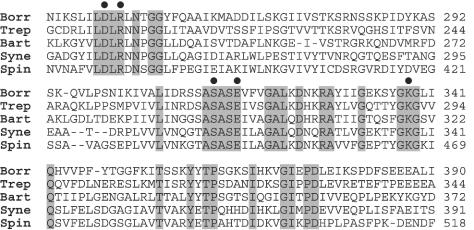

It was previously found that the outer-membrane-associated protein P13 in B. burgdorferi is processed at the C terminus by removal of the last 28 amino acids (38, 40). To identify an enzyme with potential C-terminal processing properties in B. burgdorferi, the amino acid sequence of the known CtpA protein from B. bacilliformis (36) was used to search the B. burgdorferi B31 genome by using protein PSI-BLAST (2). A gene (bb0359) was identified that maps at position 368391 to 366067 on the linear chromosome of B. burgdorferi B31 and encodes a protein with homology to the B. bacilliformis CtpA protein (20). Genes encoding possible CtpA proteases were found in a number of bacterial species and also in algae and higher plants. A putative serine protease with a low level of similarity to the CtpA protease was also identified in the archaean Sulfolobus solfataricus. In addition, similarities were found to a tail-specific protease (TSP) from E. coli and to human interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein. A comparison of the amino acid sequences of part of the CtpA protein from B. burgdorferi and potential CtpA proteases from some selected species, including Treponema, Bartonella cyanobacteria, and plants, is shown in Fig. 1. As expected, the highest level of similarity was the level of similarity between CtpA from B. burgdorferi and CtpA from the syphilis-causing spirochete Treponema pallidum (Fig. 1). Some motifs are conserved in all of the species analyzed, and the number of identical residues for the species included in Fig. 1 is 46 (data not shown). Certain residues of CtpA from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 were found to be essential for C-terminal processing of target protein and are indicated in Fig. 1 (27). Interestingly, these residues were conserved in B. burgdorferi CtpA, further demonstrating their importance for enzyme function.

FIG. 1.

Protein sequence comparison for B. burgdorferi CtpA and other proteins. The deduced amino acid sequences of parts of the CtpA proteins of B. burgdorferi B31 (Borr) (GenBank accession no. AAC66729), T. pallidum (Trep) (GenBank accession no. AAC65265), B. bacilliformis (Bart) (GenBank accession no. AAB61766), Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (Syne) (GenBank accession no. A53964), and Spinacia oleracea (spinach) (Spin) (GenBank accession no. CAA62147) were compared. The PileUp program in the Wisconsin package (version 9.1; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) was used to align the sequences. The numbers on the right are the positions of the amino acid residues in the proteins. Dashes indicate gaps introduced to optimize alignments. The shaded amino acids are identical in all proteins. Amino acids shown to be essential for enzymatic activity in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 are indicated by solid circles.

The theoretical mass of B. burgdorferi CtpA is 53,542 Da, and the pI is 8.43. However, the CtpA protein contains a putative N-terminal signal sequence for transport over the inner membrane, and the most likely cleavage site is located between positions 28 and 29; this would result in a secreted protein having 447 amino acid residues and a molecular mass of 50,397 Da.

Inactivation of the ctpA gene in B. burgdorferi.

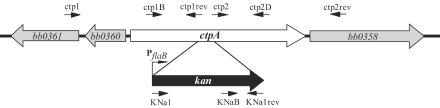

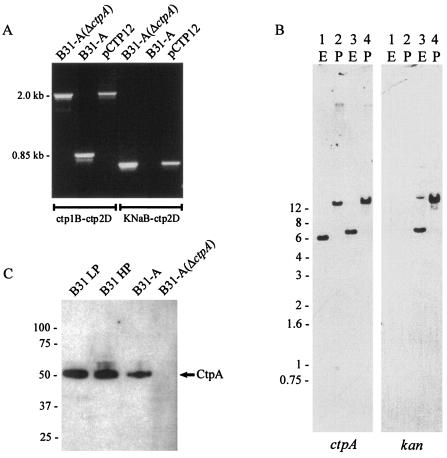

With the aim of identifying potential substrates and further investigating if the P13 protein is a substrate for the CtpA protease in B. burgdorferi, we constructed a ctpA mutant. A kan gene was inserted into the ctpA gene (Fig. 2) of high-passage B. burgdorferi strain B31-A by electroporation with plasmid pCTP12 as described above. After selection for kanamycin resistance and initial PCR screening, a putative mutant clone was used for further characterization. To show that the ctpA gene was inactivated by allelic exchange, we amplified a chromosomal region spanning the kan gene and flanking sequences (Fig. 2 and 3A). The PCR product obtained from mutant B31-A(ΔctpA) and from control plasmid pCTP12 was 2.0 kb long, while the PCR product obtained from B31-A was 0.85 kb long (Fig. 3A). To further confirm that the kan gene was inserted into the chromosome of the mutant, the KNaB primer (which binds within the kan cassette) and the ctp2D primer binding downstream of the kan insertion were used (Fig. 2 and 3A). A PCR product was obtained from the ctpA mutant but not from B31-A, as predicted (Fig. 3A). The PCR results also showed that the kan gene was inserted in the same direction as ctpA (Fig. 2 and 3A).

FIG. 2.

Inactivation of ctpA: organization of the ctpA gene and flanking genes on the B. burgdorferi B31 chromosome. The arrows indicate oligonucleotides used for construction and analysis of the ctpA mutant. The figure is not to scale.

FIG. 3.

Confirmation of kan insertion into ctpA. (A) PCR analysis of strain B31-A and kanamycin-resistant mutant B31-A(ΔctpA) with the ctp1B-ctp2D and KNaB-ctp2D primer pairs (Table 1). Plasmid pCTP12, the construct used for inactivation of the ctpA gene, was used as a control. (B) Southern blot analysis of total DNA separated in a 0.7% agarose gel. Lanes 1 and 2, wild type B31-A; lanes 3 and 4, mutant B31-A(ΔctpA). Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV (E) or PstI (P). DNA was probed with a ctpA fragment or a kan fragment generated by PCR. The positions of kilobase markers are indicated on the left. (C) Immunoblotting of total protein probed with polyclonal antiserum directed against the C-terminal half of B. burgdorferi CtpA. B31 LP was a low-passage strain. B31 HP was passed several times during in vitro cultivation. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Southern blot hybridization further confirmed the ctpA inactivation. Total borrelial DNA was digested with either EcoRV or PstI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Hybridization with a probe specific for the ctpA gene resulted in identification of a 6-kb DNA band in B31-A when the DNA was digested with EcoRV (Fig. 3B, lane 1) and a 17-kb band when it was digested with PstI (Fig. 3B, lane 2). For B31-A(ΔctpA), larger bands at about 7 kb (EcoRV digested) and 18 kb (PstI digested) were observed, corresponding to a kan insertion in the ctpA gene (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). A probe specific for the kan gene resulted in identification of only the bands in B31-A(ΔctpA) corresponding to the kan insertion into ctpA (Fig. 3B).

Synthesis of the CtpA protein in wild-type strain B31, B31-A, and B31-A(ΔctpA) was analyzed by immunoblotting with antiserum raised against the recombinant C-terminal half of the protein. The CtpA protease was expressed in low-passage infectious strain B31, as well as in the high-passage strains and in the B31-A clone used for gene inactivation, but the CtpA protease could not be detected in the B31-A(ΔctpA) mutant (Fig. 3C).

In vitro propagation of B. burgdorferi strains can result in loss of plasmids. Before further analysis of the effect of ctpA inactivation, the plasmid profiles of the B31-A strain and the B31-A(ΔctpA) mutant were compared by PCR (19). B31-A and B31-A(ΔctpA) had identical plasmid profiles and harbored the linear plasmids lp17, lp28-2, lp28-3, lp38, lp54, and lp56 and the circular plasmids cp26, cp32-1, cp32-3, cp32-4, cp32-7, cp32-8, and cp32-9 (data not shown).

Comparison of the protein profiles of B. burgdorferi B31-A and the ctpA mutant.

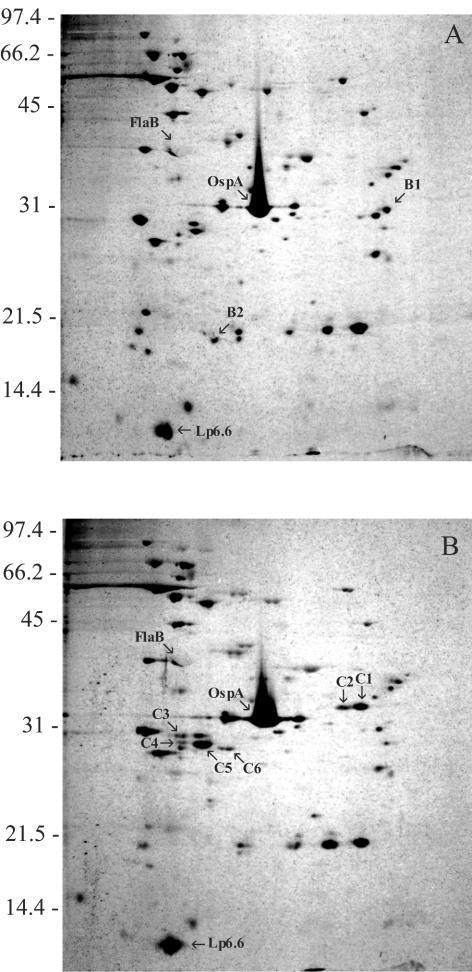

The effect of ctpA inactivation on the total protein profile was investigated by using 2D-NEPHGE and silver staining. B31-A(ΔctpA) was compared to the wild-type B31-A strain with respect to the total protein expression pattern, and differences in the protein profiles were found after inactivation of the ctpA gene (Fig. 4). In the B31-A profile, six protein spots were present that were not detected in the ctpA mutant profile. Two of these protein spots, B1 and B2, are shown in Fig. 4A. Protein spots B3, B4, B5, and B6 were seen in other gels that were visualized by using the more sensitive but less aesthetic silver stain kit from Invitrogen (data not shown). Conversely, nine protein spots present in the ctpA mutant profile were not found in the B31-A profile. Protein spots C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6 are shown in Fig. 4B. Protein spots C7, C8, and C9 were observed in other gels stained differently with the Invitrogen silver stain kit (data not shown). Our results clearly demonstrate that a number of proteins are affected by ctpA inactivation, which in turn strongly suggests that these proteins are processed by the CtpA protease in B. burgdorferi B31-A.

FIG. 4.

Two-dimensional gel analysis: silver-stained 2D-NEPHGE gels of total proteins from B. burgdorferi B31-A (A) and B. burgdorferi B31-A(ΔctpA) (B). The positions of FlaB, OspA, and Lp6.6 are indicated as references. Proteins that were expressed differently in the wild type and the ctpA mutant are indicated by designations that begin with B, and proteins that were expressed differently in the ctpA mutant strain and the wild type are indicated by designations that begin with C. The positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. The acidic ends are to the left.

Determination of potential CtpA substrates.

When 2D-NEPHGE comparisons of the wild type and mutant were used, we routinely observed six spots in the B31-A profiles that were not found in the mutant profiles, and conversely, we discriminated nine spots in the mutant profile that were not present in the B31-A profile (Fig. 4 and data not shown). In an attempt to determine the identities of the proteins, which may serve as substrates or whose synthesis may be affected by CtpA, we performed a MALDI-TOF analysis of protein spots excised from 2D-NEPHGE gels containing cell lysates from B31-A and the ctpA mutant. The results obtained are shown in Table 2. The data indicate that the channel-forming protein P13 (spots C7 and C8) and protein BB0323 (spots C1 and B1) may serve as substrates for C-terminal processing by CtpA. Not all protein spots (including B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, C2, C9, and C10) yielded peptide mass fingerprints that allowed proper protein identification. Protein spots B1 and C1 were identified as the same protein (BB0323), which was defined as a hypothetical protein (20). This protein was larger and slightly more acidic in the ctpA mutant than in the wild type, which suggests that an uncleaved C-terminal extension of the protein was present in the ctpA mutant.

TABLE 2.

MALDI-TOF identification of proteins separated by 2D-NEPHGE

| Spot | Designationa | Gene | Protein | No. of matching peptides | Sequence coverage (%) | Molecular mass (Da)b | pIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | BB0323 | bb0323 | Hypothetical membrane protein | 12 | 23 | 44,150.69 | 9.28 |

| B2 | BBA15 | ospA | Outer surface protein A (OspA) | 6 | 22 | 29,367.41 | 8.77 |

| C1 | BB0323 | bb0323 | Hypothetical membrane protein | 11 | 20 | 44,150.69 | 9.28 |

| C3 | BBA74 | oms28 | Putative porin Oms28 | 11 | 41 | 27,948.11 | 6.05 |

| C4 | BBA74 | oms28 | Putative porin Oms28 | 11 | 43 | 27,948.11 | 6.05 |

| C5 | BBA74 | oms28 | Putative porin Oms28 | 16 | 50 | 27,948.11 | 6.05 |

| C6 | BBA74 | oms28 | Putative porin Oms28 | 10 | 41 | 27,948.11 | 6.05 |

| C7 | BB0034 | p13 | Channel-forming protein P13 | 6 | 31 | 19,104.34 | 8.66 |

| C8 | BB0034 | p13 | Channel-forming protein P13 | 4 | 21 | 19,104.34 | 8.66 |

The Institute for Genomic Research gene designation.

The theoretical mass and the theoretical pI were calculated at http://us.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html.

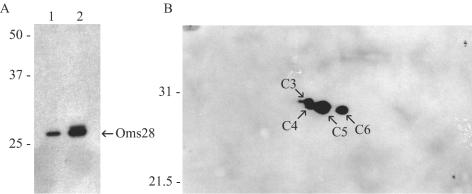

A cluster of protein spots (C3, C4, C5, and C6) was identified as Oms28, a porin in B. burgdorferi (54). A protein spot corresponding to C4 was also present in the wild-type strain B31-A profile, but the amount was smaller. An immunoblot of total-protein extracts from both wild-type cells and ctpA mutant cells probed with antiserum against Oms28 showed that the amount of Oms28 in the ctpA mutant was larger than the amount in wild-type cells (Fig. 5A). Spots C4, C5, and C6 were unique to the ctpA deletion mutant, and immunoblot analysis of proteins separated by 2D-NEPHGE with Oms28 antiserum confirmed that Oms28 was present as the different isoforms (C3, C4, C5, and C6) only in the ctpA mutant (Fig. 5B). Likewise, C7 and C8 were identified as potential isoforms of P13 by MALDI-TOF analysis, which likely represented two unprocessed versions of P13 in the mutant. In addition, spot B2 was identified as OspA in the wild-type cells.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of Oms28 synthesis. (A) Total protein of wild-type B. burgdorferi B31-A (lane 1) and the ctpA mutant (lane 2) separated by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. (B) Total protein of ctpA mutant separated by 2D-NEPHGE. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with polyclonal antiserum against Oms28. Protein spots are labeled as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left in each panel.

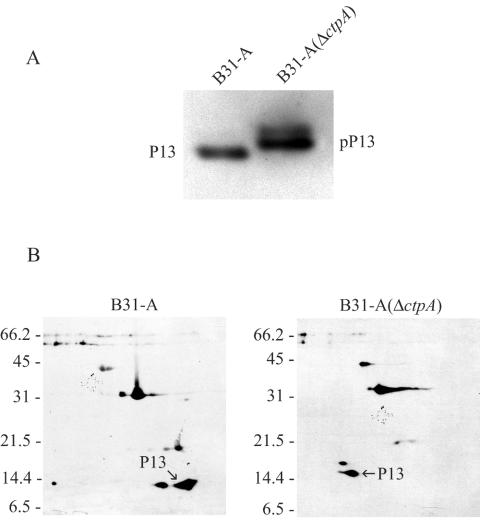

Analysis of P13 in the ctpA mutant.

B. burgdorferi B31-A(ΔctpA) was analyzed further to investigate the effect of inactivation on the previously observed C-terminal processing of P13. Western blot analysis performed with either MAb 15G6 or polyclonal rabbit serum directed against P13 provided evidence that the CtpA protease is involved in the processing of this protein. In the ctpA mutant, the P13 protein was larger, which is consistent with CtpA processing of the C terminus of this 13-kDa protein (Fig. 6A). Analysis by 2D-NEPHGE also showed that, in addition to the increase in the size of P13, P13 from the ctpA mutant has a more acidic pI than P13 from control strain B31-A (Fig. 6B). These results are in agreement with the theoretical mass and pI values for P13. Mature P13, processed both at the N terminus and at the C terminus, has a calculated molecular mass of 13,988 Da and a pI of 8.97. However, P13 not processed at the C terminus has a calculated molecular mass of 16,970 Da and a calculated pI of 8.12. These results also match the predicted pI for OspA, which was calculated to be 8.34 without the N-terminal signal sequence and the lipid moiety.

FIG. 6.

Immunoblot analysis of the effect of ctpA inactivation on P13. (A) SDS-PAGE of total protein from B. burgdorferi B31-A and B. burgdorferi B31-A(ΔctpA) transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed with MAb 15G6 directed against P13 and pP13 (precursor form). (B) 2D-NEPHGE of membrane proteins from B31-A and B31-A(ΔctpA) transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with polyclonal rabbit serum against P13. The positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left for each gel. The acidic ends are to the left.

As shown previously, P13 is an integral membrane protein with a surface exposed domain(s) (40). To investigate if P13 is present in the outer membrane of Borrelia spirochetes with an inactivated ctpA gene, protease treatment of intact spirochetes was performed. It was found that P13, but not the periplasmic flagellin protein, was cleaved by both proteinase K and trypsin (data not shown). This indicates that C-terminal processing of P13 is not needed for outer membrane localization.

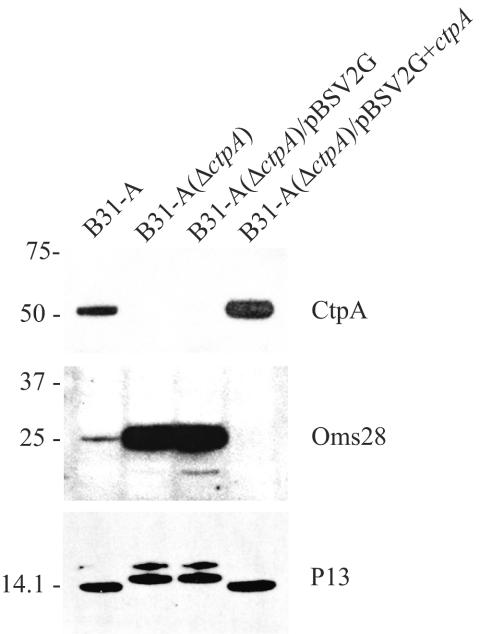

Complementation of B. burgdorferi B31-A(ΔctpA).

The B31-A(ΔctpA) mutant was transformed with the shuttle vector pBSV2G described by Elias et al. (18) containing the cloned ctpA gene and its regulatory region. As a control, the empty shuttle vector was transformed into B31-A(ΔctpA). Gentamicin-resistant colonies appeared after 7 to 8 days and were analyzed by PCR for the presence of the shuttle vector by amplifying the aacC1 gene conferring gentamicin resistance. Selected clones harboring the shuttle vector were transferred to liquid medium containing gentamicin (40 μg/ml). A clone containing the complementation plasmid and a control clone containing the empty shuttle vector were analyzed further by PCR to determine their plasmid contents. With the exception of the introduced shuttle vector, the complemented clone contained the same plasmids as the wild-type B31-A strain and the B31-A(ΔctpA) mutant (data not shown).

To investigate if the introduced plasmids were maintained as stable replicons and not integrated into the chromosome, the plasmids were successfully rescued by transformation of genomic DNA from B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G+ctpA into E. coli (data not shown). Southern blot analysis provided further evidence for the presence of the shuttle vector in the complemented ctpA mutant cells in addition to the kan gene in the ctpA locus of these cells. Hybridization with a probe specific for the ctpA gene resulted in identification of an additional band in the complemented strain corresponding to a PstI-digested pBSV2G vector with a cloned ctpA gene, and hybridization with a probe specific for aacC1 resulted in identification of the same band corresponding to the linear form of the complementation plasmid (data not shown).

To find out if the complemented ctpA mutant had the same phenotype as wild-type strain B31-A, immunoblot analyses with antibodies directed against CtpA, P13, and Oms28 were performed (Fig. 7). Interestingly, complemented strain B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G+ctpA synthesized a slightly larger amount of CtpA than wild-type strain B31-A synthesized (Fig. 7). However, a P13 protein that was the same size as the wild-type B31-A protein was detected in the complemented clone (Fig. 7). The high level of Oms28 synthesis in the ctpA mutant was restored to expression levels below that observed in the wild type. In fact, synthesis of Oms28 in the complemented ctpA mutant could not be detected by immunoblotting of proteins that were separated either by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Fig. 7) or by 2D-NEPHGE (data not shown). Further analysis showed that the pleiotropic effect on cellular proteins seen after ctpA inactivation was restored to a protein expression pattern comparable to that of the wild type in the complemented ctpA mutant (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Analysis of complementation of the ctpA mutant: immunoblot analysis of CtpA, P13, and Oms28 from B31-A (wild type), B31-A(ΔctpA) (ctpA mutant), B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G (ctpA mutant with empty shuttle vector), and B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G+ctpA (ctpA mutant with shuttle vector containing the ctpA gene). The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

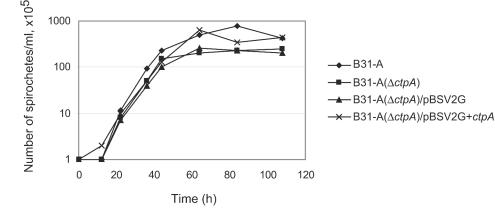

We also observed that the ctpA mutant had a lower growth rate than the wild type and that the cell densities obtained in liquid medium were lower than those of the wild type. Therefore, growth curves were determined for the wild type (B31-A), the ctpA mutant [B31-A(ΔctpA)], the complemented ctpA mutant [B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G+ctpA], and the ctpA mutant with an empty shuttle vector [B31-A(ΔctpA)/pBSV2G] by counting the spirochetes in a Petroff-Hausser chamber daily (Fig. 8). The growth rates did not differ significantly; however, the wild-type strain and the complemented mutant had stationary-phase cell densities that were about twice those of the ctpA mutant and the ctpA mutant containing an empty shuttle vector (Fig. 8). The stationary-phase cell densities of the different strains were determined in two separate experiments which produced similar results (data not shown). These experiments demonstrated that the observed phenotypic change in growth rate and the alterations in the protein profile of the ctpA mutant were direct effects of inactivation of the gene encoding this unusual protease.

FIG. 8.

Growth curves for the different strains. Bacteria were diluted to a density of 105 cells/ml, grown at 35°C in BSK-H, and counted with a microscope once or twice daily by using a Petroff-Hausser chamber.

DISCUSSION

Recently, a 13-kDa integral membrane protein (P13) of B. burgdorferi that was found to be surface exposed and processed at the C terminus was characterized (40). In this paper we present data indicating that P13 and BB0323 are substrates for the product of the ctpA gene of B. burgdorferi, which encodes a C-terminal protease. Additionally, synthesis of the Oms28 protein was upregulated in the ctpA mutant, indicating that the CtpA protease is involved in the regulation of Oms28. Our results also show that a number of unidentified proteins are affected by inactivation of ctpA as well. Prior to this study, a C-terminal processing enzyme had not been reported for the Lyme disease spirochete.

We found homologues of B. burgdorferi CtpA in a number of bacteria and also in eukaryotic species, indicating that the CtpA protease is a common enzyme that has a general biological function. So far, CtpA proteases have been characterized only for the intracellular pathogen B. bacilliformis, the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, the green alga Scenedesmus obliquus, and some higher plants (28, 36, 52, 60). In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, the CtpA protein is responsible for cleavage of the D1 precursor (pD1) polypeptide of photosystem II (PSII) (39). This C-terminal processing is essential for correct functioning of the PSII complex in plants (16). Additionally, it has been shown that the amino acid residues D253, R255, S313, E316, and K338 of CtpA of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 are critically important for the function of the protease (27). These residues are conserved and correspond to D250, R252, S313, E316, and K338 in B. burgdorferi B31 CtpA (Fig. 1), and they are likely to be involved in binding to the target or enzyme catalysis.

CtpA from the eukaryotic algae S. obliquus has been shown by X-ray crystal structure analysis to be a monomeric enzyme and to be composed of three folded domains (33). Comparisons of the secondary structure of the S. obliquus protease and the predicted secondary structure of B. burgdorferi CtpA indicate that these proteins have similar structures (data not shown). Sequence analysis of the protein revealed two conserved domains in the B. burgdorferi CtpA query sequence (2). A domain that was located between amino acids 125 and 189 in B. burgdorferi CtpA and was homologous to known PDZ motifs was identified. The PDZ domain is proposed to be the site at which the C terminus of the target protein binds (7, 33). This domain has also been found in a number of different enzymes, like phosphatases and kinases (24, 32, 44, 49). Also, a TSP domain (TSPc) located between amino acids 190 and 379 was identified. This domain, which most likely is the catalytic domain, has been shown to recognize hydrophobic regions of the substrate (7). The TSPc domain was first found in the TSP (Tsp) of E. coli as a 76-kDa periplasmic protein involved in processing of penicillin binding protein 3 (23). The predicted signal sequence indicates that CtpA is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane and thus suggests that the C-terminal processing by CtpA may occur in the periplasmic space. Other characterized CtpA proteases also contain N-terminal signal sequences (31, 36). In eukaryotic organisms, the enzyme is encoded in the nucleus and is imported from the cytosol to the thylakoid lumen of chloroplasts (41). Interestingly, in B. bacilliformis a possible alternative translation start site of the CtpA protease has been identified, and it has been speculated that this site gives rise to two forms of the protein, which are targeted to different cellular locations (36).

By comparing the protein expression profiles by using 2D-NEPHGE combined with various silver staining techniques for wild-type B. burgdorferi B31-A and a strain with an inactivated ctpA gene, we found that a number of proteins were affected by ctpA inactivation (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Proteins that were differentially expressed in wild-type strain B31-A and the ctpA mutant and therefore may be substrates for (or in other ways affected by) CtpA in B. burgdorferi were investigated by MALDI-TOF analysis and immunoblotting. In this study the BB0323 protein was identified as a potential substrate for CtpA. This protein is larger and slightly more acidic in the ctpA mutant than in the wild type, which suggests that an uncleaved C-terminal extension of this protein is present in the ctpA mutant. The function of BB0323 is unknown, and this molecule is defined as a hypothetical protein (20). This protein migrates at a position around 30 kDa as determined by SDS-PAGE, but it is predicted to be a 44-kDa protein based on the genome sequence. The explanation for this discrepancy could be that the BB0323 protein is extremely basic and has a strong positive charge at pH 7.0 and therefore migrates aberrantly during SDS-PAGE. A small variant of OspA (spot B2) was identified in wild-type strain B31-A by mass spectrometry that may be a degradation product; however, this spot was observed only in protein extracts from wild-type cells and complemented ctpA mutant cells, which argues against nonspecific protein degradation.

Different variants of Oms28 were identified by MALDI-TOF analysis and immunoblotting. This protein has been identified as a pore-forming protein (54). Expression is upregulated and additional variants of Oms28 are present in the ctpA mutant (Fig. 4 and 5). These results suggest that Oms28 is not a substrate for CtpA and that the upregulation of Oms28 is a secondary effect due to ctpA inactivation. The upregulation of Oms28 in the ctpA mutant could be the result of a lack of C-terminal processing needed for regulating an inhibitor or an activator involved in modulation of Oms28 expression. The variants of Oms28 observed in the ctpA mutant could arise from overexpression, which may cause problems for a system involved in the normal processing and modification of Oms28. The larger Oms28 fragment may be Oms28 that includes the N-terminal signal sequence (Fig. 5A).

Protein spots C7 and C8 were identified as P13 by both MALDI-TOF analysis (Table 2) and immunoblotting (Fig. 6). It is clear that P13 in the ctpA mutant is larger and has a more acidic pH, corresponding to the lack of C-terminal processing of the protein (Fig. 6). Therefore, our results strongly indicate that CtpA is the enzyme involved in the previously observed C-terminal processing of P13. The upper band of the two P13 bands produced by the ctpA mutant strain may be the N- and C-terminally unprocessed form of P13, which supports the hypothesis that inactivation of ctpA also affects the efficiency of N-terminal processing. In B. burgdorferi, P13 is processed at the C terminus by cleavage behind an alanine, which removes the last 28 amino acids (40). Similar to the P13 protein, the D1 protein of PSII is a hydrophobic membrane-spanning protein (22). In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, the last 16 amino acids of the pD1 polypeptide are removed, whereas the last 9 amino acids are removed in higher plants and 8 amino acids are removed in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii; in all cases the cleavage is behind an alanine (30, 58). These observations indicate that the processing of P13 occurs through a mechanism which is similar to the mechanism for processing of the pD1 polypeptide in photosynthetic organisms.

As P13 is still localized in the outer membrane of the ctpA knockout mutant, actual C-terminal processing does not appear to be required for transport and localization of P13 to the outer membrane. However, the 28-amino-acid C-terminal extension of P13 may be required for transportation to the outer membrane, and cleavage of these amino acids may be required for functioning or correct assembly of the P13 channel described previously (43). The target (D1 protein) of the CtpA protease in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is also transported to the cell membrane, and processing of this protein is required for optimal functioning of PSII (3, 10, 16, 30) but not for localization to the membrane (3, 39). Further experiments are needed to determine the role of C-terminal processing in the functioning of P13.

Genetic complementation by introduction of a shuttle vector with the cloned ctpA gene showed that the P13 protein was restored to the normal size (Fig. 7). In the complemented clone the synthesis of Oms28 was not detected (Fig. 7). This could be explained by the overexpression of CtpA synthesis in the complemented clone, which may lead to complete downregulation of Oms28 synthesis for this clone (Fig. 7).

We demonstrated that inactivation of the ctpA gene is not lethal for B. burgdorferi cells but that the knockout mutant stopped growing at a slightly lower cell density (Fig. 8). Genetic complementation by introduction of a shuttle vector with the cloned ctpA gene showed that the growth patterns were similar for the complemented ctpA mutant and wild-type strain B31-A (Fig. 8), and the total protein profiles were the same for the complemented strain and the wild-type strain (data not shown). Therefore, the complementation experiment confirmed that the phenotype observed after inactivation of the ctpA gene was due to the lack of expression of CtpA alone.

Since the inactivation was done in high-passage, noninfectious strain B31-A, the relevance for pathogenesis of the CtpA protease cannot be tested in any of the available animal models. In this study, we demonstrated that a number of proteins were affected by ctpA inactivation, indicating that this enzyme is involved in the processing of a number of different proteins. The CtpA protein was shown to be involved in the C-terminal processing of the integral outer-membrane-associated P13 protein, as well as the BB0323 protein, and to be possibly involved in the regulation of Oms28 synthesis in B. burgdorferi. So far, whether CtpA is directly involved in the processing of all proteins observed and whether there are secondary effects caused by the lack of normal processing of regulators or inhibitors can only be matters for speculation. The experimental data presented here provide proof that a C-terminal processing protease is present in B. burgdorferi, but further analyses are needed to determine the detailed function and the mechanism by which the CtpA protease is involved in protein processing and ultimately the importance of the C-terminal processing in the complex life cycle of B. burgdorferi spirochetes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Swedish Research Council grants 07922 and 13564, by Swedish Council for Forestry and Agricultural Research grant 23.0161, by Symbicom AB, by the Royal Academy of Science (Olof Ahlöfs Foundation), by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and by the J. C. Kempe Foundation.

We thank Abdallah Elias, Dorothee Grimm, Philip Stewart, Rebecca Thalken, and Kit Tilly for valuable help with the genetic experiments; Alan G. Barbour for providing MAb 15G6; Jonathan T. Skare for providing antiserum against Oms28; David Mead for assistance with MALDT-TOF analysis; Ingela Nilsson and Mikael Sellin for technical assistance; and Annika Nordstrand for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alban, P. S., P. W. Johnson, and D. R. Nelson. 2000. Serum-starvation-induced changes in protein synthesis and morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 146:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anbudurai, P. R., T. S. Mor, I. Ohad, S. V. Shestakov, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1994. The ctpA gene encodes the C-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of the photosystem II reaction center complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91:8082-8086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour, A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol Med. 57:521-525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour, A. G., S. L. Tessier, and S. F. Hayes. 1984. Variation in a major surface protein of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect. Immun. 45:94-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbour, A. G., S. L. Tessier, and W. J. Todd. 1983. Lyme disease spirochetes and ixodid tick spirochetes share a common surface antigenic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 41:795-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beebe, K. D., J. Shin, J. Peng, C. Chaudhury, J. Khera, and D. Pei. 2000. Substrate recognition through a PDZ domain in tail-specific protease. Biochemistry 39:3149-3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjellqvist, B., G. J. Hughes, C. Pasquali, N. Paquet, F. Ravier, J. C. Sanchez, S. Frutiger, and D. Hochstrasser. 1993. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis 14:1023-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bono, J. L., A. F. Elias, J. J. Kupko III, B. Stevenson, K. Tilly, and P. Rosa. 2000. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2445-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowyer, J. R., J. C. Packer, B. A. McCormack, J. P. Whitelegge, C. Robinson, and M. A. Taylor. 1992. Carboxyl-terminal processing of the D1 protein and photoactivation of water-splitting in photosystem II. Partial purification and characterization of the processing enzyme from Scenedesmus obliquus and Pisum sativum. J. Biol. Chem. 267:5424-5433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgdorfer, W., A. G. Barbour, S. F. Hayes, J. L. Benach, E. Grunwaldt, and J. P. Davis. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll, J. A., R. M. Cordova, and C. F. Garon. 2000. Identification of 11 pH-regulated genes in Borrelia burgdorferi localizing to linear plasmids. Infect. Immun. 68:6677-6684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll, J. A., N. El-Hage, J. C. Miller, K. Babb, and B. Stevenson. 2001. Borrelia burgdorferi RevA antigen is a surface-exposed outer membrane protein whose expression is regulated in response to environmental temperature and pH. Infect. Immun. 69:5286-5293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll, J. A., C. F. Garon, and T. G. Schwan. 1999. Effects of environmental pH on membrane proteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 67:3181-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuff, J. A., M. E. Clamp, A. S. Siddiqui, M. Finlay, and G. J. Barton. 1998. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 14:892-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diner, B. A., D. F. Ries, B. N. Cohen, and J. G. Metz. 1988. COOH-terminal processing of polypeptide D1 of the photosystem II reaction center of Scenedesmus obliquus is necessary for the assembly of the oxygen-evolving complex. J. Biol. Chem. 263:8972-8980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias, A., J. L. Bono, K. Tilly, and P. Rosa. 1998. Growth of infectious and non-infectious B. burgdorferi at different salt concentrations. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 110:863-865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias, A. F., J. L. Bono, J. J. Kupko III, P. E. Stewart, J. G. Krum, and P. A. Rosa. 2003. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias, A. F., P. E. Stewart, D. Grimm, M. J. Caimano, C. H. Eggers, K. Tilly, J. L. Bono, D. R. Akins, J. D. Radolf, T. G. Schwan, and P. Rosa. 2002. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect. Immun. 70:2139-2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, O. White, et al. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gollin, D. J., L. E. Mortenson, and R. L. Robson. 1992. Carboxyl-terminal processing may be essential for production of active NiFe hydrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEBS Lett. 309:371-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankamer, B., E. Morris, J. Nield, A. Carne, and J. Barber. 2001. Subunit positioning and transmembrane helix organisation in the core dimer of photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 504:142-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara, H., Y. Yamamoto, A. Higashitani, H. Suzuki, and Y. Nishimura. 1991. Cloning, mapping, and characterization of the Escherichia coli prc gene, which is involved in C-terminal processing of penicillin-binding protein 3. J. Bacteriol. 173:4799-4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hata, Y., S. Butz, and T. C. Sudhof. 1996. CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J. Neurosci. 16:2488-2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatchikian, E. C., V. Magro, N. Forget, Y. Nicolet, and J. C. Fontecilla-Camps. 1999. Carboxy-terminal processing of the large subunit of [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 7757. J. Bacteriol. 181:2947-2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heijne, V. 1986. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:4683-4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inagaki, N., R. Maitra, K. Satoh, and H. B. Pakrasi. 2001. Amino acid residues that are critical for in vivo catalytic activity of ctpA, the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of photosystem II. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30099-30105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inagaki, N., Y. Yamamoto, H. Mori, and K. Satoh. 1996. Carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 precursor protein: cloning and sequencing of the spinach cDNA. Plant Mol. Biol. 30:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Islam, M. R., J. H. Grubb, and W. S. Sly. 1993. C-terminal processing of human beta-glucuronidase. The propeptide is required for full expression of catalytic activity, intracellular retention, and proper phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22627-22633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivleva, N. B., S. V. Shestakov, and H. B. Pakrasi. 2000. The carboxyl-terminal extension of the precursor D1 protein of photosystem II is required for optimal photosynthetic performance of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 124:1403-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karnauchov, I., R. G. Herrmann, H. B. Pakrasi, and R. B. Klosgen. 1997. Transport of CtpA protein from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803 across the thylakoid membrane in chloroplasts. Eur. J. Biochem. 249:497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kornau, H. C., P. H. Seeburg, and M. B. Kennedy. 1997. Interaction of ion channels and receptors with PDZ domain proteins. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7:368-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao, D. I., J. Qian, D. A. Chisholm, D. B. Jordan, and B. A. Diner. 2000. Crystal structures of the photosystem II D1 C-terminal processing protease. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:749-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That, and O. Schneewind. 2001. Sortase-catalysed anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1049-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon, N. K., J. Robbins, M. Der Vartanian, D. Patil, H. D. Peck, Jr., A. L. Menon, R. L. Robson, and A. E. Przybyla. 1993. Carboxy-terminal processing of the large subunit of [NiFe] hydrogenases. FEBS Lett. 331:91-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell, S. J., and M. F. Minnick. 1997. A carboxy-terminal processing protease gene is located immediately upstream of the invasion-associated locus from Bartonella bacilliformis. Microbiology 143:1221-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagasawa, H., Y. Sakagami, A. Suzuki, H. Suzuki, H. Hara, and Y. Hirota. 1989. Determination of the cleavage site involved in C-terminal processing of penicillin-binding protein 3 of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:5890-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsson, C. L., H. J. Cooper, K. Håkansson, A. G. Marshall, Y. Östberg, M. Lavrinovicha, and S. Bergström. 2002. Characterization of the P13 membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi by mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 13:295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nixon, P. J., J. T. Trost, and B. A. Diner. 1992. Role of the carboxy terminus of polypeptide D1 in the assembly of a functional water-oxidizing manganese cluster in photosystem II of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: assembly requires a free carboxyl group at C-terminal position 344. Biochemistry 31:10859-10871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noppa, L., Y. Östberg, M. Lavrinovicha, and S. Bergström. 2001. P13, an integral membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi, is C-terminally processed and contains surface-exposed domains. Infect. Immun. 69:3323-3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oelmüller, R., R. G. Herrmann, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1996. Molecular studies of CtpA, the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of the photosystem II reaction center in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21848-21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ojaimi, C., C. Brooks, S. Casjens, P. Rosa, A. Elias, A. Barbour, A. Jasinskas, J. Benach, L. Katona, J. Radolf, M. Caimano, J. Skare, K. Swingle, D. Akins, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Östberg, Y., M. Pinne, R. Benz, P. Rosa, and S. Bergström. 2002. Elimination of channel-forming activity by insertional inactivation of the p13 gene in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 184:6811-6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponting, C. P. 1997. Evidence for PDZ domains in bacteria, yeast, and plants. Protein Sci. 6:464-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosa, P., D. S. Samuels, D. Hogan, B. Stevenson, S. Casjens, and K. Tilly. 1996. Directed insertion of a selectable marker into a circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 178:5946-5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossmann, R., M. Sauter, F. Lottspeich, and A. Bock. 1994. Maturation of the large subunit (HYCE) of Escherichia coli hydrogenase 3 requires nickel incorporation followed by C-terminal processing at Arg537. Eur. J. Biochem. 220:377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadziene, A., D. D. Thomas, and A. G. Barbour. 1995. Borrelia burgdorferi mutant lacking Osp: biological and immunological characterization. Infect. Immun. 63:1573-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samuels, D. S., K. E. Mach, and C. F. Garon. 1994. Genetic transformation of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi with coumarin-resistant gyrB. J. Bacteriol. 176:6045-6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato, T., S. Irie, S. Kitada, and J. C. Reed. 1995. FAP-1: a protein tyrosine phosphatase that associates with Fas. Science 268:411-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwan, T. G., and J. Piesman. 2000. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the lyme disease-associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:382-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwan, T. G., J. Piesman, W. T. Golde, M. C. Dolan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shestakov, S. V., P. R. Anbudurai, G. E. Stanbekova, A. Gadzhiev, L. K. Lind, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1994. Molecular cloning and characterization of the ctpA gene encoding a carboxyl-terminal processing protease. Analysis of a spontaneous photosystem II-deficient mutant strain of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19354-19359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silber, K. R., K. C. Keiler, and R. T. Sauer. 1992. Tsp: a tail-specific protease that selectively degrades proteins with nonpolar C termini. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89:295-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skare, J. T., C. I. Champion, T. A. Mirzabekov, E. S. Shang, D. R. Blanco, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, B. L. Kagan, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1996. Porin activity of the native and recombinant outer membrane protein Oms28 of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 178:4909-4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steere, A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steere, A. C., R. L. Grodzicki, A. N. Kornblatt, J. E. Craft, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, G. P. Schmid, E. Johnson, and S. E. Malawista. 1983. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevenson, B., T. G. Schwan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 63:4535-4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi, M., T. Shiraishi, and K. Asada. 1988. COOH-terminal residues of D1 and the 44 kDa CPa-2 at spinach photosystem II core complex. FEBS Lett. 240:6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tilly, K., A. F. Elias, J. L. Bono, P. Stewart, and P. Rosa. 2000. DNA exchange and insertional inactivation in spirochetes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:433-442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trost, J. T., D. A. Chisholm, D. B. Jordan, and B. A. Diner. 1997. The D1 C-terminal processing protease of photosystem II from Scenedesmus obliquus. Protein purification and gene characterization in wild type and processing mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20348-20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto, Y., N. Inagaki, and K. Satoh. 2001. Overexpression and characterization of carboxyl-terminal processing protease for precursor D1 protein: regulation of enzyme-substrate interaction by molecular environments. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7518-7525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, X., M. S. Goldberg, T. G. Popova, G. B. Schoeler, S. K. Wikel, K. E. Hagman, and M. V. Norgard. 2000. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1470-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]