Abstract

Purpose

We report updated results of magnetic resonance imaging guided partial prostate brachytherapy and propose a definition of biochemical failure following focal therapy.

Materials and Methods

From 1997 to 2007, 318 men with cT1c, prostate specific antigen less than 15 ng/ml, Gleason 3 + 4 or less prostate cancer received magnetic resonance imaging guided brachytherapy in which only the peripheral zone was targeted. To exclude benign prostate specific antigen increases due to prostatic hyperplasia, we investigated the usefulness of defining prostate specific antigen failure as nadir +2 with prostate specific antigen velocity greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year. Cox regression was used to determine the factors associated with prostate specific antigen failure.

Results

Median followup was 5.1 years (maximum 12.1). While 36 patients met the nadir +2 criteria, 16 of 17 biopsy proven local recurrences were among the 26 men who also had a prostate specific antigen velocity greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year (16 of 26 vs 1 of 10, p = 0.008). Using the nadir +2 definition, prostate specific antigen failure-free survival for low risk cases at 5 and 8 years was 95.1% (91.0–97.3) and 80.4% (70.7–87.1), respectively. This rate improved to 95.6% (91.6–97.7) and 90.0% (82.6–94.3) using nadir +2 with prostate specific antigen velocity greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year. For intermediate risk cases survival was 73.0% (55.0–84.8) at 5 years and 66.4% (44.8–81.1) at 8 years (the same values as using nadir +2 with prostate specific antigen velocity greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year).

Conclusions

Requiring a prostate specific antigen velocity greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year in addition to nadir +2 appears to better predict clinical failure after therapies that target less than the whole gland. Further followup will determine whether magnetic resonance imaging guided brachytherapy targeting the peripheral zone produces comparable cancer control to whole gland treatment in men with low risk disease. However, at this time it does not appear adequate for men with even favorable intermediate risk disease.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, brachytherapy, magnetic resonance imaging

During the last 2 decades PSA screening has led to a significant migration toward favorable risk prostate cancer.1 The recognition that many men are being overtreated for their disease combined with the desire to reduce the toxicity of therapy has led to an increased interest in subtotal/focal therapy, which aims to achieve cancer control with less toxicity by targeting only the areas of known disease within the prostate.2–7

Most prostate cancers arise in the peripheral zone of the prostate, while only a minority involve the anterior base.8 In a pathological examination of whole mount prostatectomy specimens D’Amico et al found that for men with low risk prostate cancer only 0.37% of tumor foci were in the anterior base.9 However, another group found that purely anterior lesions occurring at the base or mid gland or apex accounted for 20% of prostatectomies in men with a combination of low and higher risk disease.10 Given that the insertion of radioactive seeds into the anterior base can be associated with significant urinary toxicity in the form of obstructive symptoms for men who receive prostate brachytherapy, an attractive concept was to offer brachytherapy directed at the PZ that spared the anterior base. Therefore, in 1997 Brigham and Women’s Hospital initiated a program of subtotal prostate treatment for men with favorable risk disease which used a novel intraoperative MRI guidance system to deliver brachytherapy only to the PZ as defined on MRI.11 We report the updated results of this large single institution series of subtotal gland treatment, and evaluate whether a new definition of PSA failure may be more appropriate for use in men receiving focal therapy where BPH can persist and proliferate as well as contribute to a measurable PSA increase.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Between 1997 and 2008, 318 patients underwent MRI guided PZ prostate brachytherapy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. All men underwent 1.5 Tesla endorectal coil MRI. Patient selection was limited to those men with American Joint Commission on Cancer stage T1c disease, PSA less than 15 ng/ml and biopsy Gleason score 3 + 4 or less. This work was approved by the institutional review board of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Treatment Technique

Interstitial prostate radiation was performed using iodine-125 sources, a magnetic resonance compatible perineal template, a peripheral loading technique and an in-traoperative 0.5 Tesla MRI unit (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Intraoperatively the PZ of the prostate was selected as the clinical target volume and was identified on each axial MRI slice, as were the anterior rectal wall and prostatic urethra, by an expert MRI radiologist. A catheter loading was calculated with the goal of achieving a prescribed minimum dose to the PZ of 137 Gy. The anterior base and the transition zone anterior to the urethra were not targeted specifically and the dose to these regions was kept to less than 100%. MRI compatible catheters with iodine-125 sources (model 6711, Nycomed/ Amersham, Arlington Heights, Illinois) were placed trans-perineally under MRI guidance. The technique mandated that the end of case MRI based real-time dosimetry provided a V100 (percent of the target volume receiving 100% of the prescription dose) of 100%.12 An example of an intraoperative MRI with target definition and postoperative scan is displayed in figure 1. No patient received androgen deprivation therapy. A total of 61 (19%) patients with a PSA of 10.1 to 14.9 ng/ml, more than 50% positive biopsies, or MRI evidence of extracapsular extension at the apex or mid gland were treated with EBRT to 45 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions to the prostate and seminal vesicles, followed by a brachytherapy boost to 90 Gy, which was our standard boost dose.

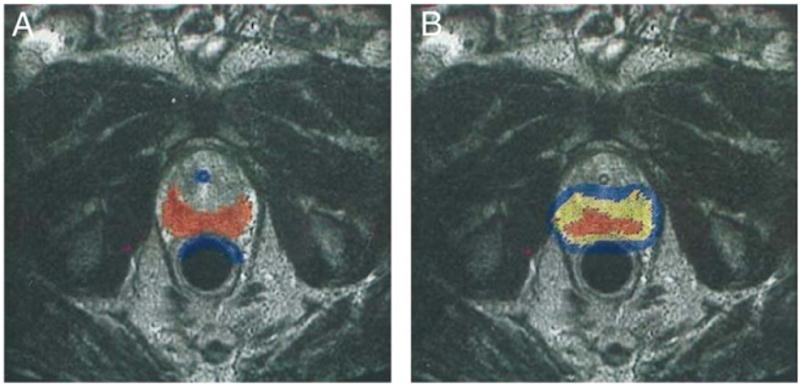

Figure 1.

Example of contoured PZ target volume (A) and post-implant dosimetry (B). Red represents contoured peripheral zone. Blue represents urethra and anterior rectal wall. After implantation of seeds yellow is 100% or more of prescription dose, red is 150% or more of prescription dose, blue is 63% or more of prescription dose and no color is less than 63% of prescription dose.

Followup and Evaluation for Local Recurrence

Digital rectal examination was performed, and serum PSA was measured every 3 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Patients with a significant increase in PSA were evaluated with an endorectal coil MRI. Those with MRI showing evidence of a possible local recurrence underwent biopsy, which was typically 12 cores.

Definition of PSA Failure

Because only the PZ was targeted, patients were at higher risk for PSA increases due to BPH of the transition zone than those who received full gland prostate irradiation. Therefore, a strict nadir +2 definition of PSA failure could overcall slow benign increases in PSA as a biochemical recurrence.13 In untreated men a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year can be a useful discriminant between prostate cancer and BPH.14,15 Therefore, we investigated the usefulness of defining PSA failure as an increase in PSA by 2 ng/ml above the nadir in which the PSAV following the nadir was greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year.

Statistical Methods

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate PSA failure-free survival using the standard nadir +2 and modified nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year definitions.16 The assumptions of the Cox model were tested and no violations were detected. Cox multivariable regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with time to PSA failure using both definitions of failure.17 Fisher’s exact test was used to compare rates of positive biopsies and MRI. All analyses were performed with SAS® 9.2 and p <0.05 was used as the 2-sided level of significance.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Patient baseline characteristics are listed in table 1. Median PSA was 5.0 ng/ml (IQR 3.8 to 6.9). Of the patients 280 (88%) had Gleason 3 + 3 disease while 38 (12%) had Gleason 3 + 4 disease.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| No. Gleason (%): | |

| 3 + 3 = 6 | 280 (88) |

| 3 + 4 = 7 | 38 (12) |

| Median ng/ml PSA (IQR) | 5.0 (3.8–6.9) |

| No. ng/ml PSA (%): | |

| 4 or Less | 95 (30) |

| Greater than 4–10 | 208 (65) |

| Greater than 10–14.9 | 15 (5) |

| No. risk (%): | |

| Low | 265 (83) |

| Intermediate | 53 (17) |

| No. more than 50% of cores pos (%) | 45 (14) |

| No. supplemental EBRT (%) | 61 (19) |

| No. nonwhite race (%) | 23 (7) |

| Median cc vol (IQR) | 38 (28–52) |

| Median pt age (IQR) | 63.3 (59.2–68.7) |

Outcomes for Entire Cohort

Median followup was 5.1 years (IQR 2.8 to 7.3, maximum 12.1). Using nadir +2, PSA failure-free survival was 91.5% (87.0–94.5) at 5 years and 78.1% (69.5–84.5) at 8 years. Using nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year, survival improved to 91.9% (95% CI 87.5–94.8) at 5 years and 86.2% (79.4–90.9) at 8 years. Distant metastases developed in 1 patient of 318 who subsequently died of prostate cancer.

Predictors and Estimates of Outcome

On multivariable analysis using the nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year outcome, the factors associated with an increased risk of PSA failure were Gleason 3 + 4 vs 6 or less (AHR 3.3, 95% CI 1.3–8.7, p = 0.016) and PSA level (AHR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.7, p <0.0001, table 2). When Gleason and PSA were collapsed into standard risk groups (ie patients with PSA 10.1 to 15 ng/ml or Gleason 3 + 4 were considered intermediate risk), the only factor associated with outcome was having intermediate vs low risk disease (AHR 4.4, 95% CI 2.0–9.7, p <0.001). Intermediate vs low risk disease was also the only significant factor (AHR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.5, p = 0.006) when the standard nadir +2 definition was used as the outcome.

Table 2.

Factors associated with time to PSA failure

| Univariable Analysis

|

Multivariable Analysis with PSA + Gleason

|

Multivariable Analysis with Risk Group

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | AHR (95% CI) | p Value | AHR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Gleason 3 + 4 | 3.34 (1.40–7.96) | 0.007 | 3.29 (1.25–8.69) | 0.016 | ||

| Gleason 3 + 3 | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — | ||

| PSA (ng/ml) | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.21–1.66) | <0.0001 | ||

| Intermediate risk | 5.21 (2.40–11.3) | <0.001 | 4.39 (1.98–9.72) | 0.0003 | ||

| Low risk | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — | ||

| % Cores pos | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.06 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.21 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.38 |

| EBRT | 1.45 (0.61–3.45) | 0.40 | 0.64 (0.15–2.76) | 0.55 | 1.08 (0.44–2.64) | 0.86 |

| No EBRT | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — |

| Nonwhite | 0.95 (0.22–4.04) | 0.95 | 0.64 (0.15–2.76) | 0.55 | 0.78 (0.18–3.37) | 0.74 |

| White | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) | — |

| Vol (cc) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.049 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.13 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.18 |

| Yr treated | 0.83 (0.67–1.04) | 0.10 | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.63 | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) | 0.37 |

| Age | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.49 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.63 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.52 |

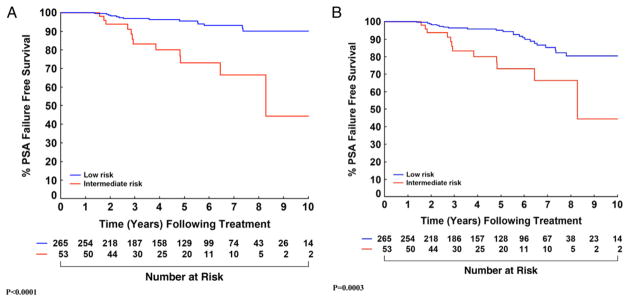

Using the nadir +2 definition, PSA failure-free survival for low risk cases at 5 and 8 years was 95.1% (91.0–97.3) and 80.4% (70.7–87.1), respectively. This improved to 95.6% (91.6–97.7) and 90.0% (82.6–94.3) using nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year. For intermediate risk cases failure-free survival was 73.0% (55.0–84.8) at 5 years and 66.4% (44.8–81.1) at 8 years regardless of the definition of failure used (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Estimates of failure-free survival stratified by low vs intermediate risk using definition of failure of modified nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year (A) and standard nadir +2 (B).

Local Recurrence Stratified by PSAV

There were 36 patients with a PSA increase more than 2 points above the nadir. Of the 26 patients with a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year, 22 had a suspicious MRI and underwent biopsy, of which 16 were positive for local recurrence. Gleason scores were 3 + 3 in 5 cases, 3 + 4 in 2, 4 + 3 in 2, 4 + 4 in 1, 3 + 5 in 1 and 4 + 5 in 2, and 3 cases were ungraded. Of the 10 patients with nadir +2 but PSAV 0.75 ng/ml or less per year, 2 had a suspicious MRI and both underwent 12-core biopsy, resulting in 1 finding of a local recurrence with Gleason 3 + 3 = 6.

Evidence to Support

Modified Definition of PSA Failure

Of the 36 patients who met the nadir +2 criteria, the 26 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year were noticeably different from the 10 with PSAV 0.75 ng/ml or less per year as displayed in table 3. Only 2 of the 10 men with PSAV 0.75 ng/ml or less per year had MRI suspicious for local recurrence, compared to 22 of 26 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year (2 of 10 vs 22 of 26, p <0.001). In addition, 16 of the 17 biopsy proven local recurrences were among the 26 men with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year (16 of 26 vs 1 of 10, p = 0.008). The median PSADT for those men with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year was 11.01 months, which was significantly shorter (p <0.001) than the 25.09 month PSADT of the 10 with PSAV 0.75 ng/ml or less per year. Finally, only 1 of the 10 men with PSAV 0.75 ng/ml or less per year had any unfavorable risk factors (PSA greater than 10 ng/ml or Gleason 7), while 12 of the 26 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year had presented with unfavorable factors (1 of 10 vs 12 of 26, p = 0.06).

Table 3.

Comparison of patients who met nadir+2 criteria

| PSAV Greater Than 0.75 ng/ml/yr | PSAV Less Than 0.75 ng/ml/yr | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts | 26 | 10 | |

| No. MRI suspicious for local recurrence (%) | 22 (85) | 2 (20) | <0.001 |

| No. biopsy pos for local recurrence (%) | 16 (62) | 1 (10) | 0.008 |

| Median mos PSADT | 11.0 | 25.1 | |

| No. initially intermediate risk (%) | 12 (46) | 1 (10) | 0.06 |

DISCUSSION

The increasing awareness that many men with prostate cancer are being overtreated has led to increased interest in focal therapy as a middle ground that aims to achieve reasonable cancer control with fewer side effects than whole gland treatment. To our knowledge this is the largest single institution series of subtotal prostate gland treatment with curative intent for prostate cancer.

Among patients with low risk disease PSA failure-free survival was 95.1% at 5 years (95.6% using nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year) and 80.4% at 8 years (90.0% using nadir +2 with PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year). These rates are similar to the 95% 5-year result seen among low risk patients in the 921 patient multi-institutional whole gland series reported by Hinnen et al18 and comparable to the 8-year result of 82% for low risk disease in the 2,693 patient multi-institutional whole gland series of Zelefsky et al.19 If these results continue to hold up with longer followup, then future patients with low risk disease might consider a PZ only approach, which was shown in a previous publication of this series to result in a lower need for α1-blockers (19%),20 and significantly less intense 3-month patient assessed urinary obstructive and irritative symptoms (p = 0.02) compared to whole gland brachytherapy.21

While patients in this study had only a maximum PSA of 15 ng/ml and a maximum Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7, we found that even these favorable intermediate risk patients unfortunately had a much higher risk of failure after partial gland treatment compared to low risk patients, with an AHR of 4.4. Among our patients with favorable intermediate risk disease PSA failure-free survival was only 73.0% at 5 years and 66.4% at 8 years (regardless of failure definition used), which was noticeably poorer than the 87% at 5 years in the series by Hinnen et al18 and 71% at 8 years in the series by Zelefsky et al for intermediate risk disease.19

Equally concerning is that in a series of 809 men receiving whole gland brachytherapy monotherapy with median D90 greater than 180 Gy Cosset et al showed that 5-year PSA control for Gleason 7 disease with PSA less than 10 ng/ml (94%) or Gleason 6 with PSA 10 to 15 ng/ml (95%) was close to the 5-year PSA control for standard low risk disease (97%).22 The fact that patients with favorable intermediate risk disease can achieve excellent results with whole gland therapy but not partial gland therapy suggests that they may be undertreated with partial gland ablation, which may reflect the greater propensity for multifocality with Gleason 7 disease.23 Therefore, patients with even favorable intermediate risk disease currently appear to be poor candidates for focal ablative therapies. Whether excluding those patients with a pretreatment PSAV greater than 2 ng/ml per year or using modern multiparametric 3 Tesla endorectal MRI to better evaluate the anterior prostate can help identify good candidates for subtotal gland therapy among intermediate risk patients remains the subject of further study.24,25

Another important contribution from this study is insight into an appropriate definition of PSA control for patients who receive focal therapy. There is increasing interest in techniques such as partial gland high intensity focused ultrasound or hemi-gland cryoablation. Both of these techniques will leave a substantial portion of the benign gland untreated and there is no consensus as to how to define success or failure after focal therapy.26 The current ASTRO (American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology)-Phoenix nadir +2 definition of failure after radiotherapy assumes that the entire gland has been treated,13 in which case an increase of 2 points above a nadir value is likely to represent true cancer recurrence. However, for men with only partially treated glands, BPH can cause PSA to increase slowly with time and make it difficult to differentiate benign increases due to BPH from true cancer recurrence.

We propose that the definition of PSA recurrence after subtotal gland treatment should require a nadir +2 and a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year, which borrows from the screening literature where incorporation of a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year improves the specificity of prostate cancer detection compared to the use of PSA thresholds alone.14,15 In our study 16 of 17 biopsy proven local recurrences were in the 26 men who met the nadir +2 and the PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year criteria (p = 0.008). Of these 26 men 22 had an MRI suspicious for recurrence compared to only 2 of the 10 with a PSAV of 0.75 ng/ml or less per year. The 10 patients who met the nadir +2 criteria but had a PSAV of 0.75 ng/ml or less per year also had a longer PSADT, which is associated with a lower likelihood of harboring clinically significant disease. Finally, 9 of these 10 patients also presented with low risk disease, making it less likely that they would experience true recurrence.

A few points deserve further consideration. Although our maximum followup was long at more than 12 years, median followup was only 5.1 years, partially reflecting the fact that a proportion of our patients lives distantly and came to our institution solely for this MRI guided procedure and did not continue followup with us. In addition, a limitation to our claim that incorporating a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng/ml per year criteria improves the accuracy of failure determinations after subtotal gland treatment is a possible ascertainment bias. Specifically not all patients with an increasing PSA underwent biopsy and so it is not possible to know exactly what percentage of men meeting the nadir +2 criteria with a PSAV less than 0.75 ng/ml per year harbored occult local recurrence. However, all patients with an increasing PSA did undergo endorectal MRI to help determine whether biopsy was warranted, and there is growing evidence that modern multiparametric MRI is useful for detecting recurrences.27 While the transition zone was not specifically targeted, it did receive some scatter radiation from the implant. Therefore, it is plausible that the expected PSA increase due to BPH should be somewhat less in these partially treated patients than in those purely untreated. This may be less of an issue for other more focal therapies that target a lesion rather than the entire PZ. Finally, it is possible that post-brachytherapy transient PSA bounce contributed to some of these PSA increases, and the appropriate definition of PSA bounce after subtotal therapy is the subject of future studies.

In summary, further followup will determine whether MRI guided brachytherapy targeting the peripheral zone produces long-term cancer control comparable to that of whole gland treatment in men with low risk disease. However, at this time subtotal therapy does not appear adequate for men with even favorable intermediate risk disease. Requiring a PSAV greater than 0.75 ng.ml per year in addition to nadir +2 appears to better predict clinical failure after therapies that target less than the whole gland. Further studies with systematic biopsies of all men with increasing PSA will be needed to validate this modified definition. However, as there is currently no consensus on the appropriate definition of failure after focal therapy and little evidence to substantiate any other definition, this appears to be a reasonable starting point for further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grants NIH P41-RR019703 and BRP-CA111288, the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award, and grants from David and Cynthia Chapin; from Richard, Nancy and Karis Cho, and from an anonymous Family Foundation.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- EBRT

external beam radiotherapy

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- PSADT

prostate specific antigen doubling time

- PSAV

prostate specific antigen velocity

- PZ

peripheral zone

References

- 1.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, et al. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onik G, Narayan P, Vaughan D, et al. Focal “nerve-sparing” cryosurgery for treatment of primary prostate cancer: a new approach to preserving potency. Urology. 2002;60:109. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahn DK, Silverman P, Lee F, Sr, et al. Focal prostate cryoablation: initial results show cancer control and potency preservation. J Endourol. 2006;20:688. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert EH, Bolte K, Masson P, et al. Focal cryosurgery: encouraging health outcomes for unifocal prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:1117. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onik G, Vaughan D, Lotenfoe R, et al. The “male lumpectomy”: focal therapy for prostate cancer using cryoablation results in 48 patients with at least 2-year follow-up. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:500. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madersbacher S, Pedevilla M, Vingers L, et al. Effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound on human prostate cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed HU, Freeman A, Kirkham A, et al. Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Urol. 185:1246. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reissigl A, Pointner J, Strasser H, et al. Frequency and clinical significance of transition zone cancer in prostate cancer screening. Prostate. 1997;30:130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970201)30:2<130::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Amico AV, Davis A, Vargas SO, et al. Defining the implant treatment volume for patients with low risk prostate cancer: does the anterior base need to be treated? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:587. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koppie TM, Bianco FJ, Jr, Kuroiwa K, et al. The clinical features of anterior prostate cancers. BJU Int. 2006;98:1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amico AV, Tempany CM, Schultz D, et al. Comparing PSA outcome after radical prostatectomy or magnetic resonance imaging-guided partial prostatic irradiation in select patients with clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urology. 2003;62:1063. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Amico AV, Cormack R, Tempany CM, et al. Real-time magnetic resonance image-guided interstitial brachytherapy in the treatment of select patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:507. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H, Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter EJ, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA. 1992;267:2215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barak M, Cohen M, Mecz Y, et al. The additional value of free prostate specific antigen to the battery of age-dependent prostate-specific antigen, prostate-specific antigen density and velocity. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1997;35:475. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1997.35.6.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Roy Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinnen KA, Battermann JJ, van Roermund JG, et al. Long-term biochemical and survival outcome of 921 patients treated with I-125 permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1433. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelefsky MJ, Kuban DA, Levy LB, et al. Multi-institutional analysis of long-term outcome for stages T1–T2 prostate cancer treated with permanent seed implantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurwitz MD, Cormack R, Tempany CM, et al. Three-dimensional real-time magnetic resonance-guided interstitial prostate brachytherapy optimizes radiation dose distribution resulting in a favorable acute side effect profile in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Tech Urol. 2000;6:89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo PH, D’Amico AV, Clark JA, et al. Assessing a prostate cancer brachytherapy technique using early patient-reported symptoms: a potential early indicator for technology assessment? Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:38. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cosset JM, Flam T, Thiounn N, et al. Selecting patients for exclusive permanent implant prostate brachytherapy: the experience of the Paris Institut Curie/Cochin Hospital/Necker Hospital group on 809 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouraviev V, Mayes JM, Sun L, et al. Prostate cancer laterality as a rationale of focal ablative therapy for the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:906. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Roehl KA, et al. Preoperative PSA velocity and the risk of death from prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Amico AV, Renshaw AA, Sussman B, et al. Pretreatment PSA velocity and risk of death from prostate cancer following external beam radiation therapy. JAMA. 2005;294:440. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed HU, Emberton M. Benchmarks for success in focal therapy of prostate cancer: cure or control? World J Urol. 28:577. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamada T, Sone T, Jo Y, et al. Locally recurrent prostate cancer after high-dose-rate brachytherapy: the value of diffusion-weighted imaging, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, and T2-weighted imaging in localizing tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:408. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]