Abstract

σE, a sporulation-specific sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis, is formed from an inactive precursor (pro-σE) by a developmentally regulated processing reaction that removes 27 amino acids from the proprotein's amino terminus. A sigE variant (sigE335) lacking 15 amino acids of the prosequence is not processed into mature σE but is active without processing. In the present work, we investigated the sporulation defect in sigE335-expressing B. subtilis, asking whether it is the bypass of proprotein processing or a residual inhibition of σE activity that is responsible. Fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that sigE335-expressing B. subtilis progresses further into sporulation (stage III) than do strains lacking σE activity (stage II). Consistent with its stage III phenotype, and a defect in σE activity rather than its timing, the sigE335 allele did not disturb early sporulation gene expression but did inhibit the expression of late sporulation genes (gerE and sspE). The Spo− phenotype of sigE335 was found to be recessive to wild-type sigE. In vivo assays of σE activity in sigE, sigE335, and merodiploid strains indicate that the residual prosequence on σE335, still impairs its activity to function as a transcription factor. The data suggest that the 11-amino-acid extension on σE335 allows it to bind RNA polymerase and direct the resulting holoenzyme to σE-dependent promoters but reduces the enzyme's ability to initiate transcription initiation and/or exit from the promoter.

Endospore formation is a process in which some bacterial species are able to respond to unfavorable growth conditions by differentiating into dormant spores. This phenomenon has been most intensely studied in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis (reviewed in references 20, 25, and 32). Early in its sporulation program, B. subtilis partitions itself into two unequal compartments that are contained within a common cell wall. The smaller compartment (forespore), the endospore precursor, is subsequently engulfed by the larger mother cell compartment. The mother cell then nurtures the resulting prespore during its maturation. When development is complete, the mother cell lyses, releasing the spore into the environment. The temporal and compartment-specific gene expression that drives the sporulation process is largely orchestrated through modifications of the differentiating cell's RNA polymerase (RNAP) (reviewed in reference 16). This involves the sequential exchange of the RNAP's sigma factor subunits: σE and then σK in the mother cell and σF and then σG in the forespore. sigE, the structural gene for the first mother cell sigma factor (σE), is expressed at the onset of sporulation under the control of the spore gene activator protein, Spo0A (15). In addition to transcriptional regulation, σE synthesis is controlled posttranslationally (17, 30). The initial protein product of sigE is an inactive σE precursor (pro-σE) (17). Pro-σE is converted to σE at a later stage in sporulation by the removal of 27 amino acids from the pro-σE amino terminus (17, 33). B. subtilis strains that fail to convert pro-σE to σE have the same Spo− phenotype as those with null mutations in sigE itself (23, 33). The SigE prosequence not only silences σE's activity but also tethers the proprotein to the cell membrane for processing and enhances its stability (4, 5, 6, 11, 23, 24).

The processing of σE begins approximately 1 h after the onset of pro-σE synthesis and determines the time at which σE becomes active (17, 33). The gene for the enzyme (SpoIIGA) responsible for pro-σE processing is coexpressed with sigE but not activated until the mother cell and forespore compartments form (5, 10, 17, 30). The trigger for SpoIIGA activation is a signal protein (SpoIIR) that is synthesized in the newly formed forespore and whose presence is communicated to the mother cell (7, 14, 18, 19). Details of this process are reviewed in reference 16.

In a previous study of the prosequence of σE, a mutant sigE allele was constructed in which amino acids 2 to 17 encoded by the sigE prosequence were deleted (sigE335) (23). sigE335 encodes a product that is not processed into mature σE but is active without processing (23). σE335-like proteins are routinely used to demonstrate whether particular spore genes are under σE control, based on their coincident transcription with σE335 in vegetatively growing B. subtilis (26, 29, 30). Although σE335 can direct RNAP to σE-dependent promoters, B. subtilis expressing sigE335 as the sole source of σE is Spo− (23). The present work attempts to distinguish between two plausible mechanisms for sigE335's Spo− phenotype: (i) disruption of sporulation due to the uncoupling of σE335's activity from the processing reaction and (ii) an unrecognized residual inhibition of a σE activity due to the remaining prosequence element. The data obtained in this study argue for the latter mechanism, with the residual 11-amino-acid prosequence permitting the formation of a σE335 holoenzyme that can recognize and bind to σE-dependent promoters but impairing an initiation event that occurs subsequent to promoter binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. pWH63 is pUS19 with a 3.4-kbp EcoRI/BamHI fragment from pGSIIG3 (31) encoding the entire spoIIG operon (i.e., PspoIIG spoIIGA sigE). pSM31 is sigE335 on a 1.1-kbp PstI fragment, cloned into pUS19 with a 1.4-kbp EcoRI/PstI segment from pGSIIG3. The element from pGSIIG3 carries the spoIIG promoter and a portion of spoIIGA. The resulting plasmid places sigE335 under the control of PspoIIG for expression in B. subtilis. Transcriptional fusions of sporulation genes to lacZ were introduced into JH642 by transformation or transduction. Once their published expression patterns were verified in this wild-type strain, the fusions were transferred into sigE mutant strains by transformation with chromosomal DNA from JH642.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or features | Source, construction, or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pUS19 | Apr Spcr | 1 |

| pSR5 | Apr KmrspoIID::lacZ | 27 |

| pWH63 | Apr SpcrspoIIGA-B | spoIIGAB→pUS19 |

| pSM31 | Apr Spcr PspoIIG sigE335 | PspoIIG sigE335→pUS19 |

| SPβ sspE::lacZ | SPβ sspE::lacZ Emr Cmr | C. Moran |

| SC118 | SPβ gerE::lacZ Emr Cmr | L. Kroos |

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | J. Hoch |

| SM30 | JH642 SPβ spoIID::lacZ | C. Moran |

| SM31 | sigE335 Cmr | 23 |

| SM34 | sigE335 Kmr | 23 |

| SM37 | sigE335/sigE | pWH63→SM34 |

| SM38 | sigE335 SPβ spoIID::lacZ | SM30→SM34 |

| SM41 | JH642(pSGMU31ΔZ) sigE::lacZ | 9 |

| SM46 | sigE335/sigE SPβ spoIID::lacZ | SM30→SM37 |

| SM48 | spoIID::lacZ | pSR5→JH642 |

| SM54 | spoIIGB::erm trpC2 pheA1 | Laboratory strain |

| SM59 | sigE335 spoIID::lacZ | pSR5→SM34 |

| SM90 | SPβ sspE::lacZ | SPβ sspE::lacZ→JH642 |

| SM91 | sigE335 sspE::lacZ | SM90→SM34 |

| SM92 | spoIIGB::erm sspE::lacZ | SM90→SM54 |

| SM95 | SPβ gerE::lacZ | SPβ gerE::lacZ→JH642 |

| SM96 | sigE335 gerE::lacZ | SM95→SM34 |

| SM97 | spoIIGB::erm gerE::lacZ | SM95→SM54 |

| SM117 | sigE sigE::lacZ | pWH63→SM41 |

| SM119 | sigE335 sigE::lacZ | pSM31→SM41 |

| SM128 | sigE335/sigE spoIID::lacZ | pSM31→SM48 |

Fluorescence microscopy of sporulation phenotypes.

B. subtilis cells from an isolated colony that had formed on Difco sporulation (DS) agar after 18 h at 37°C, were suspended in 2 μl of H2O on a microscope slide and then mixed with 1 μl of a solution of FM4-64 (1 to 10 μg/ml) and/or Mito Traker Green FM (10 to 50 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Cells were viewed with an Olympus BX-50 fluorescence microscope with images captured by an Orca ER digital camera with Meta Vue imaging software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, Pa.). FM4-64 was observed with Olympus filter set UMWG (510-550 exciter filter, 515-590 barrier filter), and Mito Traker Green FM was observed with the UN1BA2 filter combination (470-490 exciter filter, 515-550 barrier filter).

Western blot analyses.

B. subtilis grown in DS medium (DSM) was harvested at intervals after the cessation of exponential growth (onset of sporulation). Crude protein extracts were prepared as previously described (33). Protein samples equivalent to 2.5 ml of sporulation culture were precipitated with 2 volumes of cold ethanol, suspended in sample buffer, and fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (12% acrylamide). Following electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose and blocking of the nitrocellulose with BLOTTO, the protein bands were probed with an anti-σE monoclonal antibody (33). Bound antibody was visualized with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat immunoglobulin against mouse immunoglobulin (HyClone Laboratories Inc.).

β-Galactosidase assays.

B. subtilis strains carrying lacZ fused to spoIID, sigE, gerE, or sspE were grown in DSM and harvested at various times during growth and sporulation. The data displayed in each figure are representative of the results obtained in three or more separate experiments. Cells were stored frozen at −20°C until assayed. Cell pellets were resuspended in Z buffer, treated with lysozyme (21), and permeabilized with chloroform-sodium dodecyl sulfate (15). β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described by Miller (22).

Determination of sporulation frequencies.

B. subtilis strains to be tested were inoculated into DSM and incubated with shaking for 24 h at 37°C. Culture samples were diluted 1/10 into 2 ml of minimal medium salt base (23), chloroform (100 μl) was added, and after mixing, the cell suspensions were incubated for 30 min at 80°C. Samples of treated and untreated cultures were diluted and plated on DSM for CFU counting.

General methods.

DNA manipulations and transformation of Escherichia coli were done by following standard protocols. Transformation of competent B. subtilis cells was carried out by the method of Yasbin et al. (34).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SigE335 phenotype.

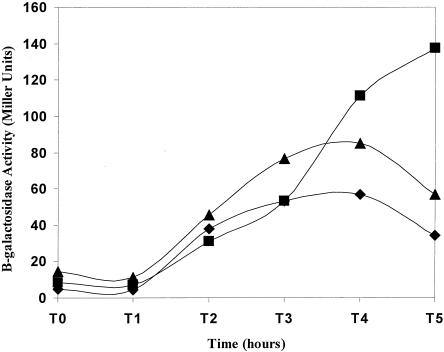

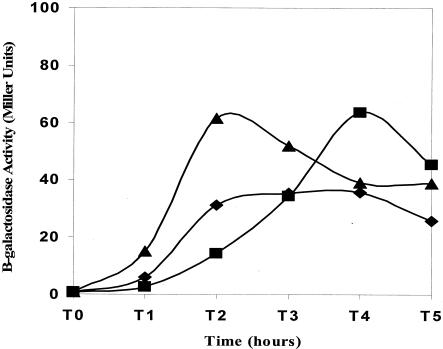

A sigE allele whose product lacks amino acids 2 to 17 of the 27-amino-acid sigE-encoded prosequence is both active without processing and unprocessable into mature σE (23). Although active as a transcription factor, σE335 lacks an essential quality of the wild-type σE protein. B. subtilis strains expressing σE335 as their sole source of σE are Spo− (23). The σE activities in a sigE335-expressing B. subtilis strain and a congenic strain with wild-type sigE are illustrated in Fig. 1. In this example, as in previous studies, both strains carry an autonomously replicating plasmid (pSR5) encoding an E. coli lacZ gene under the transcriptional control of the σE-dependent spoIID promoter. σE-dependent β-galactosidase activity becomes evident in both strains at 1 to 2 h after the onset of sporulation, after which time the β-galactosidase levels in the wild-type strain decline, while those in the sigE335-expressing strain persist. The decline in σE activity in the wild-type strain and not in the σE335 strain likely reflects ongoing differentiation and the changeover from σE- to σK-dependent transcription in wild-type B. subtilis, while the σE335-expressing strain is arrested at a stage in development at which σE activity persists.

FIG. 1.

Expression of plasmid-encoded spoIID::lacZ in wild-type, sigE335 mutant, and sigE/sigE335 mutant B. subtilis strains. B. subtilis strains carrying pSR5 (spoIID::lacZ) and expressing either wild-type sigE (SM48) (♦), sigE335 (SM59) (▪), or sigE/sigE335 (SM128) (▴) were grown in DSM at 37°C. Samples were taken at the indicated hourly intervals after the cultures left exponential growth (T0) and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods.

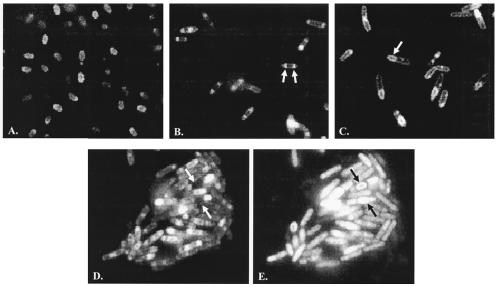

To characterize the stage of sporulation at which the sigE335 allele arrests development, we plated wild-type, sigE::erm (SigE−), and sigE335 strains on DSM and examined samples for their terminal phenotypes by fluorescence microscopy. The cells were exposed to the fluorescent membrane stain FM4-64 for visualization prior to viewing. Figure 2 illustrates micrographs taken from isolated colonies after a 24-h incubation on DSM plates. The wild-type strain (Fig. 2A) displays abundant spores, both free and within sporangia. SigE− strains progress normally to the formation of the mother cell and forespore compartments but then, unable to express σE-dependent inhibitors of polar septation, fail to block the formation of a second septum (3). This second septum appears at the cell pole opposite that at which the first septum formed. Approximately 70% of the SigE− cells that we viewed following the 24-h incubation (77 of 113) displayed the abortive disporic terminal phenotype that is characteristic of SigE− strains, with the remaining cells showing no apparent sporulation-associated membrane changes (Fig. 2B). Consistent with σE335's transcriptional activity and Spo− phenotype, the fluorescence micrograph of this variant displayed neither a disporic phenotype of the SigE− strain nor mature spores of the Spo+ parent. Instead, 36% of the cells (91 of 250) had progressed to a stage at which an engulfed prespore protoplast is visible within the mother cell compartment (Fig. 2C). The remaining cells had membrane features typical of vegetative cells. FM4-64 is unable to diffuse into the cell interior and stain organelles that have become totally internalized (28). The sigE335 strain's prespores, by virtue of their staining with FM4-64, reflect structures that are still attached to the mother cell membrane and available to the dye. A second fluorescent membrane stain (Mito Traker Green FM) can diffuse into the cell's interior and stain prespores that have separated from the mother cell membrane (28). Panels D and E of Fig. 2 display a grouping of cells stained with both FM4-64 and Mito Traker Green and viewed separately with filter sets that will allow detection of either the FM4-64 or the Mito Traker signal. A number of prespores can be seen (arrows) that stain with Mito Traker (Fig. 2E) but not with FM4-64 (Fig. 2D). On the basis of multiple viewings, we estimate that approximately 17% of the prespores that are stained with Mito Traker Green are not stainable with FM4-64. We interpret the microscopy data as evidence that sporulation in the sigE335 mutant strain is arrested at a point in development after engulfment of the forespore by the mother cell but in most cases prior to release of the prespore into the mother cell interior (i.e., prior to the completion of stage III). On the basis of the terminal phenotype of the sigE335-expressing strain, σE335 has sufficient σE activity to inhibit the formation of the second sporulation septum but insufficient activity to allow the bacterium to advance beyond stage III of development. If the block is due to premature rather than inadequate σE activity, this activity is not enough to disrupt the early morphological changes of forespore septum formation or engulfment.

FIG. 2.

Micrographs of stained sporulating B. subtilis. Wild-type (JH642) (A), SigE− (SM54) (B), and SigE335 (SM34) (C to E) B. subtilis strains were cultured for 24 h on DS agar at 37°C. Bacteria were suspended in water on a microscope slide, and their membranes were visualized with either FM4-64 (A to D) or Mito Traker Green FM (E) by fluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the double septa in panel B and an engulfed prespore in panel C. Panels D and E illustrate the same fields of cells stained with both dyes and visualized with different filter combinations. The arrows represent cells with prespores stained by Mito Traker Green and not by FM4-64.

An additional type of inappropriate σE activity would be the failure to restrict σE-dependent transcription to the mother cell. Perhaps freeing σE's activation from the processing event required to activate the wild-type protein can lead to active σE in both compartments. To explore this possibility, we examined the distribution of green fluorescent protein, expressed from the σE-dependent spoIID promoter, in the sigE335 strain. Arguing against such a model, we found that the σE-dependent fluorescent signal was limited to the mother cell compartment (data not shown).

sigE/sigE335 merodiploid.

The inability of the sigE335-expressing strain to sporulate while it is still able to transcribe σE-dependent genes suggests that the disruption in the sporulation process might be caused by inappropriate σE activity because of an uncoupling of σE activation from the septation event, the absence of an essential activity in σE335 that is present in the wild-type protein, or both. To help distinguish between inappropriate σE activity and inadequate σE activity, we created a merodiploid strain expressing both the sigE335 and wild-type sigE alleles. If sigE335's Spo− phenotype is due to inappropriate σE335 activity, we would expect sigE335 to be dominant over wild-type sigE and the merodiploid to display a Spo− phenotype. Alternatively, if σE335 lacks a property of the wild-type protein, the wild-type allele should be dominant and the merodiploid strain should be Spo+.

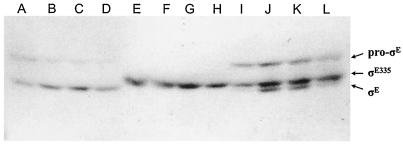

The intact sigE operon (spoIIGA sigE), with its promoter, was transformed into the sigE335 strain on an E. coli plasmid incapable of replication in B. subtilis but encoding an antibiotic resistance gene (Spcr) selectable in B. subtilis. Selection for plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance (Spcr) would be expected to yield transformants in which the plasmid integrated by single-site (also known as Campbell-like) recombination into the B. subtilis chromosome at sigE, creating a sigE335/sigE merodiploid strain. The resulting Spcr transformant clones formed brown colonies, typical of Spo+ clones, when spotted on DS agar. Representative Spcr transformants were analyzed by Western blotting for the appearance of SigE proteins during sporulation. As seen in Fig. 3, a putative sigE/sigE335 strain expressed both pro-σE and σE335, with the former processed into mature σE as sporulation proceeds.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analyses of sigE-expressing B. subtilis. B. subtilis JH642 (SigE+) (lanes A to D), SM34 (sigE335) (lanes E to H), and SM37 (sigE335/sigE) (lanes I to L) were grown in DSM; harvested at 1 (lanes A, E, and I), 2 (lanes B, F, and J), 3 (lanes C, G, and K), and 4 (lanes D, H, and L) h after the onset of sporulation; and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-σE monoclonal antibody. The positions of pro-σE, σE335, and σE in the gel system are indicated on the right.

The apparent Spo+ phenotype of the merodiploid strain on DS agar suggests that the wild-type sigE allele is dominant over sigE335. To better judge this sporulation phenotype, cultures of wild-type, sigE335 mutant, and sigE/sigE335 merodiploid strains were allowed to sporulate in liquid DSM and analyzed for the presence of heat- and chloroform-resistant spores (see Materials and Methods). Sixty-six percent of the CFU present in the wild-type culture survived this treatment, and 1.1% of the sigE335 mutant cells and 50% of the merodiploid cells formed colonies after exposure to heat and chloroform. Thus, the merodiploid strain's sporulation efficiency is comparable to that of wild-type B. subtilis. The Spo+ phenotype of the merodiploid strain is also reflected in the pattern of its spoIID::lacZ activity. σE-dependent β-galactosidase activities in both the wild-type and merodiploid strains rise and fall in unison; however, the absolute level of β-galactosidase synthesized in the merodiploid strain is approximately 50% higher than that seen in the SigE+ strain (Fig. 1).

The ability of the wild-type sigE allele to correct the Spo− phenotype of the sigE335-expressing strain argues that either the principal defect in the latter strain is the absence of an activity provided by wild-type sigE, or if it is an inappropriate σE335 activity that causes the Spo− phenotype, this activity must be restricted in the presence of the wild-type gene product.

Sporulation transcription in a sigE335 mutant.

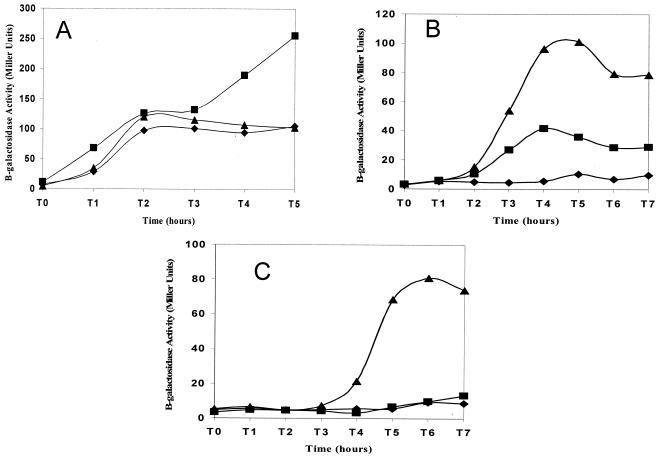

We next examined the effect of the sigE335 mutation on the expression of several sporulation operons that are activated at different times in development. The first operon that we examined was spoIIG, the transcription unit that encodes sigE itself. spoIIG is one of several operons (spoIIG, spoIIE, and spoIIA) that are induced at the onset of sporulation, approximately 1 to 1.5 h before pro-σE processing activation (32). spoIIG is transcribed by RNAP containing the principal vegetative cell sigma factor, σA. Previous work demonstrated σA displacement from RNAP concomitant with the activation of σE (13). σE335, active upon synthesis, could plausibly interfere with the activities of preexisting σ factors, thereby reducing early spore gene expression and contributing to the strain's Spo− phenotype. To test this, B. subtilis expressing sigE::lacZ, in lieu of sigE (i.e., SigE−), and congenic strains expressing either sigE or sigE335, in addition to sigE::lacZ, were allowed to enter sporulation in DSM and assayed at intervals for PspoIIG-dependent β-galactosidase activity. PspoIIG activity was found to be indistinguishable during early sporulation (T0 to T3) in wild-type, SigE−, and sigE335 B. subtilis (Fig. 4A), but by 4 h, spoIIG expression in the σE335 strain increased relative to that seen in either the SigE+ or the SigE− strain. The persistence of the spoIIG expression in the sigE335 strain is highly reproducible and presumably is a function of the stage at which sporulation is arrested in the sigE335 mutant. The inability of the sigE335 allele to interfere with the expression of spoIIG suggests that σE335 may not have full σE activity.

FIG. 4.

Expression of sporulation genes in sigE335-expressing B. subtilis. SigE+ (SM117) (▴), SigE− (SM41) (♦), and SigE335 (SM119) (▪) strains of B. subtilis carrying lacZ fused to spoIIG (A), sspE (B), or gerE (C) were grown in DSM. Cells were harvested at the onset of sporulation (T0) and at hourly intervals thereafter (T1, T2…) and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

The expression patterns of two additional sporulation genes (sspE and gerE) were examined to further test the notion that σE335's activity is deficient. sspE expression is driven by σG-containing RNAP, a forespore-specific enzyme whose full activity requires a σE-dependent event (21). sspE::lacZ activity is virtually undetectable in a SigE− strain (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the idea that the sigE335 allele inhibits late sporulation processes, sspE promoter activity in the sigE335 strain is approximately one-third of that seen in the SigE+ strain (Fig. 4B). Thus, although the sigE335 strain progresses to a point in sporulation where σG would normally be expected to be active (i.e., stage III), full σG activity is not realized in this strain.

To examine late sporulation gene expression in the compartment where ongoing development would be most influenced by σE activity, we focused on gerE. gerE is transcribed by the second mother cell-specific σ factor, σK, a transcription factor whose synthesis is directly dependent on σE (16, 36). As shown in Fig. 4C, gerE promoter activity in the sigE335 strain is no greater than that seen in a SigE− background. The inability of the σE335 protein to inhibit the spoIIG promoter and the absence of σK activity in the sigE335 strain argue that even though σE335 can display significant activity on the spoIID promoter (Fig. 1), it is defective in some aspect of σE-dependent transcription.

Copy number effects on σE-dependent transcription.

The dominance of the wild-type sigE allele over sigE335 was not expected, given the significant σE activity displayed on the spoIID promoter (Fig. 1). The reporter system that was used in that analysis, and earlier studies, consisted of a spoIID::lacZ fusion on a multicopy plasmid. In light of the present findings, we asked whether the elevated copy number of the reporter system might be masking a critical difference between the σE335 and σE activities and reexamined the ability of σE335 to mimic wild-type σE's activity on a single-copy spoIID::lacZ fusion (SPβ spoIID::lacZ). Results obtained with this reporter system (Fig. 5) had a number of significant differences from those of the previous experiment. The peak of σE335-dependent β-galactosidase accumulation was similar in amount to that seen in the wild-type strain but displayed a 2-h lag. At the time in sporulation when σE-dependent activity is greatest in the wild-type strain (T2), the spoIID::lacZ activity of the mutant strain is only 25% of that value. Apparently, the residual prosequence on σE335 compromises σE335's activity as a transcription factor in a way that is compensated for by the multiple-copy reporter system (Fig. 1). The low initial σE activity seen with the single-copy reporter gene (Fig. 5) offers an explanation why σE335, present at nearly maximum levels early in sporulation (Fig. 3), both fails to disrupt early gene expression (Fig. 4A) and activates spoIID in the multicopy system in unison with wild-type σE (Fig. 1), even though the wild-type protein's activity should be delayed, relative to that of σE335, by the processing event.

FIG. 5.

Expression of prophage-encoded spoIID::lacZ in wild-type, sigE335 mutant, and sigE/sigE335 mutant B. subtilis strains. B. subtilis SM30 (sigE) (▴), SM38 (sigE335) (▪), and SM46 (sigE/sigE335) (♦) carrying SPβ spoIID::lacZ were grown in DSM at 37°C. At the onset of sporulation (T0) and at the indicated times, samples were taken and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

How might an increase in promoter copy number elevate σE335 but not σE activity on the spoIID promoter? A plausible, albeit speculative, model envisions σE-dependent transcription in the sigE335 and wild-type strains being limited by different features of their respective σE proteins. σE-containing RNAP (E-σE) is sufficient for expression of spoIID; nevertheless, maximum β-galactosidase levels in the single-copy and multicopy spoIID::lacZ reporter systems are essentially the same in the wild-type strain. In contrast, at those times when the wild-type strains exhibited their maximum level of reporter gene activity, the sigE335-expressing strains displayed approximately four times as much activity from the multicopy reporter system as from the single-copy spoIID::lacZ system. This implies that E-σE abundance, and not promoter copy number, is the principal limiting factor restricting the level of spoIID expression in the wild-type strain, while the sigE335-expressing strain has additional σE-dependent activity, which is limited by the number of target promoters.

When we examined σE activity in the sigE/sigE335 strain with the multicopy reporter system, the presence of the sigE335 allele raised the spoIID expression level by 50% over that seen in the wild-type strain (Fig. 1); however, the level seen in the wild-type strain was halved by the presence of the sigE335 allele in the SPβ spoIID::lacZ system (Fig. 5). This suggests that the σE335 protein is not only less active than σE but that when promoter number is restricted, it is able to inhibit wild-type E-σE's ability to access the spoIID promoter. This would be the expected result if σE335 is able to form an RNAP holoenzyme that binds the spoIID promoter but is not able to efficiently initiate transcription and escape the promoter. Such prolonged occupancy of the spoIID::lacZ promoter by E-σE335 would restrict access by the more active E-σE holoenzyme and reduce the overall rate of transcription.

σK, the replacement for σE in the mother cell, is also synthesized as an inactive proprotein (pro-σK). Although the prosequences of σE and σK have features in common such as the tethering of the respective σ factors to the cell membrane and the silencing of their transcriptional activities, they are likely to have unique properties (8, 11, 12, 17, 35). The σK prosequence, when joined to the σE amino terminus, cannot substitute for the σE prosequence and allow σE to accumulate in B. subtilis (2). In addition, the prosequence of σK prevents pro-σK binding to RNAP, while pro-σE can be found bound to RNAP in B. subtilis extracts (13, 17, 35). In vitro, the σK prosequence inhibits both holoenzyme formation (i.e., the binding of pro-σK to RNAP) and E-σK interaction with promoter DNA (8). Removal of as few as 6 amino acids from the 20-amino-acid σK prosequence creates a σK factor that stimulates in vitro transcription 30-fold more than does mature σK (8). σE335's in vivo activities suggest that the loss of 15 of σE's 27 prosequence amino acids allows for promoter binding but relatively poor transcription initiation and promoter clearance relative to those of mature σE. In vitro analyses of the biochemical properties of pro-σE, σE335, and σE should provide interesting insights into how the σE prosequence explicitly modifies σE's activities and how this differs from the modifications that are caused by the σK prosequence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB 0090325. S.M. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32-AI-07271.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson, A. K., and W. G. Haldenwang. 1993. Regulation of σB levels and activity in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:2347-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson, H. C., S. Lu, L. Kroos, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1996. Exchange of precursor-specific elements between pro-σE and pro-σK of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:546-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichenberger, P., P. Fawcett, and R. Losick. 2001. A three-protein inhibitor of polar septation during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1147-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fawcett, P., A. Melnikov, and P. Youngman. 1998. The Bacillus SpoIIGA protein is targeted to sites of spore septum formation in a SpoIIE-independent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 28:931-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita, M., and R. Losick. 2002. An investigation into the compartmentalization of the sporulation transcription factor σE in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 43:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmeister, A. 1998. Activation of the proprotein transcription factor pro-σE is associated with its progression through three patterns of subcellular localization during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:2426-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmeister, A. E. M., A. Londoño-Vallejo, E. Harry, P. Stragier, and R. Losick. 1995. Extracellular signal protein triggering the proteolytic activation of a developmental transcription factor in B. subtilis. Cell 83:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson, B. D., and A. J. Dombroski. 1997. The role of the pro sequence of Bacillus subtilis σK in controlling activity in transcription initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31029-31035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonas, R. M., H. K. Peters III, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1990. Phenotype of Bacillus subtilis mutants altered in the precursor-specific region of σE. J. Bacteriol. 172:4178-4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas, R. M., E. A. Weaver, T. J. Kenney, C. P. Moran, Jr., and W. G. Haldenwang. 1988. The Bacillus subtilis spoIIG operon encodes both σE and a gene necessary for σE activation. J. Bacteriol. 170:507-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ju, J., and W. G. Haldenwang. 2003. Tethering of the Bacillus subtilis σE proprotein to the cell membrane is necessary for its processing but insufficient for its stabilization. J. Bacteriol. 185:5897-5900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju, J., and W. G. Haldenwang. 1999. The “pro” sequence of the sporulation-specific σ transcription factor σE directs it to the mother cell side of the sporulation septum. J. Bacteriol. 181:6171-6175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju, J., T. Mitchell, H. K. Peters III, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1999. Sigma factor displacement from RNA polymerase during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 181:4969-4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karow, M. L., P. Glaser, and P. J. Piggot. 1995. Identification of a gene, spoIIR that links the activation of σE to the transcriptional activity of σF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2012-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenny, T. J., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 1987. Organization and regulation of an operon that encodes a sporulation-essential sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 169:3329-3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroos, L., and Y.-T. N. Yu. 2000. Regulation of σ factor activity during Bacillus subtilis development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaBell, T. L., J. E. Trempy, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1987. Sporulation-specific σ factor, σ29 of Bacillus subtilis, is synthesized from a precursor protein, P31. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:1784-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Londoño-Vallejo, J. R. 1997. Mutational analysis of the early forespore/mother-cell signaling pathway in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 143:2753-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londoño-Vallejo, A., and P. Stragier. 1995. Cell-cell signaling pathway activating a developmental transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 13:377-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Losick, R., P. Youngman, and P. J. Piggot. 1986. Genetics of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 20:625-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason, J. M., R. H. Hackett, and P. Setlow. 1988. Regulation of expression of gene coding for small, acid-soluble proteins of Bacillus subtilis spores: studies using lacZ gene fusion. J. Bacteriol. 170:239-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Peters, H. K., III, H. C. Carlson, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1992. Mutational analysis of the precursor-specific region of Bacillus subtilis σE. J. Bacteriol. 174:4629-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters, H. K., III, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1991. Synthesis and fractionation properties of SpoIIGA, a protein essential for pro-σE processing in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:7821-7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piggot, P. J., and J. G. Coote. 1976. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:908-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popham, D. L., and P. Stragier. 1991. Cloning, characterization, and expression of the spoVB gene of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:7942-7949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rong, S., M. S. Rosenkrantz, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1986. Transcriptional control of the Bacillus subtilis spoIID gene. J. Bacteriol. 165:771-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp, M. D., and K. Pogliano. 1999. An in vivo membrane fusion assay implicates SpoIIIE in the final stages of engulfment during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14553-14558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, K., and P. Youngman. 1993. Evidence that the spoIIM gene of Bacillus subtilis is transcribed by RNA polymerase associated with σE. J. Bacteriol. 175:3618-3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stragier, P., C. Bonamy, and C. Karmazyn-Campelli. 1988. Processing of a sporulation sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis: how morphological structure could control gene expression. Cell 52:697-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stragier, P., J. Bourvier, C. Bonamy, and J. Szulmajster. 1984. A developmental gene product of Bacillus subtilis homologous to the sigma factor of Escherichia coli. Nature 312:376-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stragier, P., and R. Losick. 1996. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:297-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trempy, J. E., J. Morrison-Plummer, and W. G. Haldenwang. 1985. Synthesis of σ29, an RNA polymerase specificity determinant, is a developmentally regulated event in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 161:340-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasbin, R. E., G. A. Wilson, and F. E. Young. 1973. Transformation and transfection of lysogenic strains of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Bacteriol. 113:540-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, B., A. Hofmeister, and L. Kroos. 1998. The prosequence of pro-σK promotes membrane association and inhibits RNA polymerase core binding. J. Bacteriol. 180:2434-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng, L., and R. Losick. 1990. Cascade regulation of spore coat gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 212:645-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]