Abstract

The expression of genes involved in nitrate respiration in Bacillus subtilis is regulated by the ResD-ResE two-component signal transduction system. The membrane-bound ResE sensor kinase perceives a redox-related signal(s) and phosphorylates the cognate response regulator ResD, which enables interaction of ResD with ResD-dependent promoters to activate transcription. Hydroxyl radical footprinting analysis revealed that ResD tandemly binds to the −41 to −83 region of hmp and the −46 to −92 region of nasD. In vitro runoff transcription experiments showed that ResD is necessary and sufficient to activate transcription of the ResDE regulon. Although phosphorylation of ResD by ResE kinase greatly stimulated transcription, unphosphorylated ResD, as well as ResD with a phosphorylation site (Asp57) mutation, was able to activate transcription at a low level. The D57A mutant was shown to retain the activity in vivo to induce transcription of the ResDE regulon in response to oxygen limitation, suggesting that ResD itself, in addition to its activation through phosphorylation-mediated conformation change, senses oxygen limitation via an unknown mechanism leading to anaerobic gene activation.

Bacillus subtilis senses extracellular oxygen limitation and adapts to a new environment by switching to anaerobic metabolism (for reviews see references 50 and 51). When nitrate is available under anaerobic conditions, B. subtilis undergoes nitrate respiration. To successfully switch from aerobic growth to nitrate respiration, the ResD-ResE two-component signal transduction system must be activated, which allows induction of genes that function in nitrate respiration, including fnr (encoding the anaerobic gene regulator Fnr), nasDEF (encoding the nitrite reductase operon), and hmp (encoding the flavohemoglobin) (29, 46, 52, 63). Activation of the signal transduction system commences by sensing by ResE of unidentified signals, followed by autophosphorylation at the conserved histidine residue. The phosphoryl residue is then transferred to the N-terminal aspartate of the cognate response regulator ResD, which leads to activation of the target genes.

Most response regulators consist of two domains, a conserved N-terminal receiver (regulatory) domain and a variable C-terminal effector domain (for a review see reference 62). The receiver domains of response regulators are doubly wound α/β proteins with a central five-strand parallel β sheet surrounded by five α helices, suggesting that there is a common mechanism for phosphorylation and phosphorylation-mediated signal transmission. ResD belongs to an OmpR subfamily whose C-terminal region has a winged helix-turn-helix motif (for reviews see references 26 and 40). Structural analyses of response regulators of this class have been described for each domain (9, 28, 39, 54, 61) and for a full-length protein (11, 59). These structural studies revealed an overall similarity, as well as characteristic differences, among the members of the same family of response regulators. The most apparent differences are seen in the recognition helix, α3, and in the activation loop between α2 and α3 in the effector domain (11, 54). Despite the assignment of OmpR and PhoB to the same subfamily, with the activation loop implicated as the region that directly interacts with RNA polymerase (RNAP) in each case, the former interacts with the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the RNAP α subunit (αCTD) (1, 57, 60) and the latter interacts with σ70 (38).

OmpR and PhoB bind to the target sites in a tandem array; the recognition helix of each protein penetrates the major groove, and a β hairpin wing interacts with the minor groove (9, 18, 19, 21, 37). PhoB has been shown to dimerize upon phosphorylation (17), which increases the DNA binding affinity to the target element. In addition, the receiver domain of PhoB interferes with the DNA binding activity in the C terminus. The isolated CTD of PhoB efficiently binds the target DNA in vitro and activates the pho regulon in vivo, indicating that the receiver domain silences the DNA binding activity, which is released by phosphorylation (16, 37). In the case of OmpR, the effect of phosphorylation on the activity of the effector domain is more complex. Unlike PhoB, neither unphosphorylated nor phosphorylated OmpR forms a dimer in solution (2), yet phosphorylation increases the DNA binding affinity of OmpR (2, 20). The isolated CTD of OmpR is unable to activate transcription (64, 65) unless a stable dimer is artificially generated by introduction of a Cys residue into the C terminus (64). These results suggest that the contribution of phosphorylation to activation of the effector domain in OmpR is not to relieve inhibition by the receiver domain. One possible reason for this difference in intramolecular communication between the two response regulators is the difference in the linker region connecting the two domains. Both the length of the linker (41) and the extent of the domain interface (59) are believed to contribute differently to the activation mechanisms of response regulators through intramolecular communication.

A novel mode of a dimerization interface between receiver domains was recently reported for B. subtilis PhoP, a response regulator belonging to the OmpR/PhoB subfamily that is involved in pho regulation (for a review see reference 22). The protein-protein interface includes surface A (α4, β5 loop β5-α5, and α5) of one monomer and surface B (α3, loop β4-α4, and α4) of another monomer. This asymmetric interface formation leaves free surfaces A and B from each monomer, which function in multimer formation (7, 12). This unique interface interaction satisfactorily explains the previous observation that unphosphorylated PhoP forms a dimer and binds the target DNA, although phosphorylation moderately stimulates the binding affinity (36). Phosphorylation of PhoP may enhance cooperative DNA binding or interactions with other proteins involved in transcriptional activation (7, 36).

As shown by the studies described above, each response regulator in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily exhibits unique properties for dimerization, the effect of phosphorylation on the DNA binding ability, and transcriptional activation. In order to obtain a full understanding of how ResD activates transcription of the target genes, detailed analysis of ResD both in vivo and in vitro is required. ResD was shown to be a monomer regardless of phosphorylation (69). Previous studies showed that ResD activates transcription by directly interacting with upstream regulatory regions of the target genes (49, 69). Unphosphorylated ResD is able to bind the target DNA, and the binding affinity was only moderately stimulated by phosphorylation. In this study we further examined how ResD interacts with DNA to activate transcription and whether phosphorylation is essential for the activation. Our results indicate that ResD activates transcription of the target genes in a phosphorylation-dependent and -independent manner when B. subtilis encounters oxygen limitation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

All B. subtilis strains used in this study are derivatives of JH642 (trpC2 pheA1) (Table 1). Escherichia coli DH5α was used to propagate plasmids, and E. coli transformants were selected on Luria broth (LB) agar supplemented with 25 μg of ampicillin per ml. ResD and ResE proteins were overproduced in E. coli ER2566 and were purified by using the IMPACT system (New England Biolabs), in which the inducible self-cleaving intein tag is used.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | J. A. Hoch |

| LAB2135 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet | 52 |

| ORB4599 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspank-hy resD (pMMN546) | This study |

| ORB4600 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspank-hy resD (D57A) (pMMN547) | This study |

| ORB4605 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (pMMN546) | This study |

| ORB4606 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (D57A) (pMMN547) | This study |

| ORB4612 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (pMMN546) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN288 (fnr-lacZ) | This study |

| ORB4613 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (pMMN546) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392 (nasD-lacZ) | This study |

| ORB4614 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (pMMN546) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML107 (hmp-lacZ) | This study |

| ORB4616 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (D57A) (pMMN547) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN288 (fnr-lacZ) | This study |

| ORB4617 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (D57A) (pMMN547) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392 (nasD-lacZ) | This study |

| ORB4618 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::Pspank-hy resD (D57A) (pMMN547) SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML107 (hmp-lacZ) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| PDR111 | Integration plasmid with Pspank-hy, Ampr Spcr | 10 |

| PTYB4 | Expression vector with self-cleavable intein tag | New England Biolabs |

| pXH22 | pTYB2 carrying resD | 69 |

| pMMN424 | pTYB4 carrying resE | 49 |

| pMMN539 | pTYB4 carrying resD (D57A) | This study |

| pMMN546 | pDR111 carrying resD | This study |

| pMMN547 | pDR111 carrying resD (D57A) | This study |

To express wild-type resD and a mutant (D57A) resD from the isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Phyperspank (Pspank-hy) promoter, plasmids pMMN546 and pMMN547 were constructed. The wild-type resD gene was amplified by PCR by using oligonucleotides oMN02-205 and oMN02-206 (the oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2). The PCR product, after digestion with SalI and SphI, was cloned into pDR111 (10) that was digested with the same enzymes to generate pMMN546. The mutant resD (D57A) gene was amplified by a two-step PCR. Two overlapping PCR products were generated with the oMN02-205-oMN03-221 and oMN02-206-oMN03-220 primer pairs. Primers oMN03-220 and oMN03-221 are mutagenic primers. The resultant PCR products were used as templates for a second PCR in which primers oMN02-205 and oMN02-206 were used. The product of the second PCR was cloned into pDR111 by using a method similar to that used for construction of pMMN546 in order to generate pMMN547. The resD primary structure in pMMN546 and pMMN547 was verified by DNA sequencing. pMMN546 and pMMN547 were used to transform JH642 with selection for spectinomycin resistance (Spcr) (75 μg/ml), and transformants (ORB4599 and ORB4600, respectively) were screened for the amylase-negative phenotype that is indicative of a double recombination event at the amyE locus. LAB2135 (ΔresDE) was transformed with chromosomal DNA prepared from ORB4599 and ORB4600 to generate ORB4605 and ORB4606, respectively. SPβ phage lysate carrying fnr-lacZ (52), nasD-lacZ (48), or hmp-lacZ (49) was used to transduce ORB4599 and ORB4600 with selection for chloramphenicol resistance (5 μg/ml) (the resulting strains ORB4612 to ORB4614 and ORB4616 to ORB4618 are listed in Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| oMN98-19 | GGAATTCAAAATGTGAATGA |

| oMN98-20 | CGGGATCCATTACCAACAA |

| oMN98-22 | CGGGATCCGATTGTTTTGTT |

| oMN98-24 | GGAATTCAGAGGTGGCGTTA |

| oMN98-25 | CGGGATCCAGCAATTCATAC |

| oMN99-89 | GGAATTCCCAAAACATAAGT |

| oMN99-90 | CGGGATCCAGTGCTTTTAAT |

| oMN00-102 | CAGGGGGAAACCATGGACCAAA |

| oMN00-103 | GCTTTTCCAAAATTTCACCCGGGTTCAGCGCCGACCT |

| oMN02-205 | AGATAAGTCGACAGAAGGAAAGCAGGG |

| oMN02-206 | GCATAAGCATGCCTACTACGCTTTTCC |

| oMN03-220 | ATTTTGCTTGCTCTGATGATGCC |

| oMN03-221 | GGCATCATCAGAGCAAGCAAAAT |

| oHG-1 | TATCTCTTCAATGGCCCTTA |

| oHG-5 | GTTAGTCCGTTTTTGCTA |

| oHG-6 | CCTTTCGAAAAGATGTAT |

| oHG-7 | AAATGCCCGGTTTTAAGG |

Restriction enzyme sites used for cloning are underlined.

ResD (D57A) was overproduced in ER2566 carrying pMMN539. The mutant resD gene was amplified by PCR by using oligonucleotide primers oMN00-102 and oMN00-103 and pMMN547 as the template. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and SmaI and ligated with pTYB4 (New England Biolabs), which was digested with the same enzymes, to generate pMMN539.

Purification of proteins.

ResD and ResE were overproduced in E. coli ER2566 carrying pXH22 (69) and pMMN424 (49), respectively. For ResE purification, E. coli was grown in LB with ampicillin at 30°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.5 to 0.6, at which point IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. The cells were then incubated at 30°C for an additional 4 h before they were harvested. The cell pellets were suspended in buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol) and were broken by passage through a French press. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was applied to a chitin column. After the column was washed with buffer B (24 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol), it was flushed with buffer B containing 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and kept at 4°C overnight to cleave the intein tag. After elution with buffer B, pooled fractions containing ResE proteins were applied to a High-Q column, and the proteins were eluted with a linear salt gradient (100 to 500 mM NaCl) in buffer B. The fractions containing ResE were combined, dialyzed against 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-100 mM NaCl-5% glycerol, and stored at −70°C.

For ResD purification E. coli ER2566 strains carrying pXH22 (wild-type ResD) and pMMN539 (D57A mutant) were grown in LB at 30°C, and the expression of resD was induced as described above for resE heterologous overexpression. The cell lysate was prepared by using a method similar to the method used for ResE, except that streptomycin sulfate (1.5%, wt/vol) was added to precipitate nucleic acids with centrifugation at 40,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a chitin column and washed with buffer C (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2) and then with buffer D (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 25 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2). After cleavage of the intein tag with 30 mM DTT, ResD was eluted with buffer D. Pooled ResD-containing fractions were loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column equilibrated with buffer D. ResD was eluted with buffer E (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2). The protein was dialyzed against buffer F (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and stored at −70°C.

RNAP was purified from B. subtilis MH5636 (wild type) (58), which produces the RNAP β′ subunit fused to a 10-His tag. Cells were grown in 2× YT (47) and harvested around 2 h after the end of exponential growth. Purification of RNAP by using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid has been described elsewhere (35, 58).

Hydroxyl radical footprinting.

The DNA probes hmp (positions −133 to 27 with respect to the transcription start site) and nasD (positions −185 to 66), which were used for footprinting, were amplified by PCR by using primers oHG-5 and oHG-6 and primers oMN98-19 and oMN98-20, respectively. To end label coding or noncoding strands, one member of each primer pair was treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. DNA probes generated by PCR by using one labeled primer and one unlabeled primer were separated on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and purified with an Elutip-d column (Schleicher and Shuell) as described previously (49).

Hydroxyl radical footprinting was performed as described previously (67), with minor modifications. ResD or ResE or both were incubated in 20 μl of binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM DTT, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM ATP) for 10 min at room temperature. Labeled DNA probe (50,000 cpm) was added, and the reaction mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The cleavage reaction was initiated by simultaneously mixing 2 μl of 1 mM Fe EDTA-0.1 M DTT-1% H2O2 with the protein-DNA complex. After incubation for 2 min at room temperature, the cleavage reaction was stopped by adding 25 μl of stop solution (4% glycerol, 0.6 M sodium acetate [pH 5.0], 0.1 mg of yeast RNA per ml). The reaction mixture was extracted with 50 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (pH 6.8) and was precipitated with ethanol. The pellet was resuspended with 3.5 μl of loading buffer (90% formamide, 0.04% bromophenol blue, 0.04% xylene cyanol in Tris-borate buffer) and heated for 1.5 min at 90°C before it was loaded onto an 8% polyacrylamide-urea gel. The same primer that was used for labeling of the probe was used for dideoxy sequencing with a Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals), and the sequencing reactions were performed together with the footprinting reactions. The gel was electrophoresed at 60 W and dried, and then it was analyzed by using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

In vitro runoff transcription.

The linear templates used for in vitro transcription assays were amplified by PCR by using primers oMN99-89 and oMN99-90 (positions −185 to 79 of hmp), primers oHG-7 and oHG-1 (positions −138 to 96 of nasD), and primers oMN98-24 and oMN98-25 (positions −169 to 96 of fnr). In order to determine the start sites of transcripts, different hmp (positions −185 to 61) and nasD (positions −138 to 66) templates were used, which were amplified with primers oMN99-89 and oMN98-22 and primers oHG-7 and oMN98-20, respectively. PCR products were purified with a QIA PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The in vitro transcription buffer contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM ATP, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 10% glycerol, and 0.4 U of RNasin RNase inhibitor (Promega) per μl. ResD or ResE or both were incubated in 20 μl of transcription buffer at room temperature for 10 min. RNAP and templates were added at final concentrations of 25 and 5 nM, respectively, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. ATP, GTP, and CTP (each at a concentration of 100 μM), UTP (25 μM), and 5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol) were added to start transcription. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, 10 μl of stop solution (1 M ammonium acetate, 100 μg of yeast RNA per ml, 30 mM EDTA) was added. The reaction mixture was precipitated with ethanol, and the pellet was dissolved in 3.5 μl of loading dye solution (7 M urea, 100 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue). Transcripts were analyzed on an 8% polyacrylamide-urea gel. RNA markers were prepared by using the Decade marker system protocol (Ambion Inc.).

Phosphorylation of ResD by ResE.

ResE (1 μM) with or without 1 μM ResD (wild-type or the D57A mutant protein) was incubated in 50 μl of transcription buffer containing 0.22 μM [γ-32P]ATP at room temperature. After incubation for 5, 10, and 15 min, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was added to 4.5 μl of 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.3 M DTT, 0.1% bromophenol blue). The protein samples were separated on an SDS—12% polyacrylamide gel, and the dried gel was analyzed by using a phosphorimager.

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity.

B. subtilis cells were grown aerobically and anaerobically in 2× YT supplemented with 1% glucose, 0.2% potassium nitrate, and appropriate antibiotics in the absence or presence of 1 mM IPTG. The anaerobic cultures were prepared by filling tubes with a cell suspension as described previously (52). Cells were inoculated (starting optical density at 600 nm, 0.02) from cultures grown overnight on DS agar medium (47). Samples were withdrawn at time intervals, and β-galactosidase activity was determined as previously described (47) and was expressed in Miller units (42).

RESULTS

ResD binds tandemly to upstream regions of the hmp and nasD promoter.

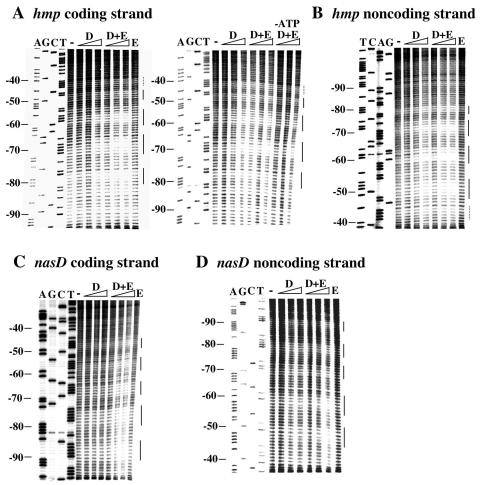

A previous DNase I footprinting analysis revealed that ResD interacts directly with upstream regulatory regions of the anaerobically induced genes hmp, nasD, and fnr (49). ResD binds to the region at approximately positions −40 to −75 relative to the transcription start sites of the hmp and nasD promoters and to the region at approximately positions −48 to −62 of the fnr promoter (49). Because some regions showed intrinsic resistance to DNase I, it was difficult to delimit the binding sites. In order to localize the binding sites more precisely and also to examine the contacts between ResD and the DNA backbone, a hydroxyl radical footprinting analysis was carried out (Fig. 1). ResD protected five regions between positions −40 and −85 of the coding and noncoding strands of hmp. The protected regions were separated by approximately 10 bp except for the two binding sites proximal to the promoter, which were separated by 5 bp. There are five protected regions separated by 10 bp between positions −45 and −95 of the coding and noncoding strands of nasD. The protected regions obtained by using ResD in the presence of ResE were similar to those obtained with ResD alone; however, the phosphorylation of ResD stimulated the binding of ResD to the target DNA, especially in the hmp regulatory region. The protection of the hmp coding strand by ResD was not enhanced in the presence of ResE if ATP was omitted from the reaction mixture, indicating that the stimulatory effect of ResE is dependent on ATP. We did not obtain reproducible results for hydroxyl radical footprinting for fnr, probably due to the low binding affinity of ResD to the fnr regulatory region, as shown previously (49).

FIG. 1.

Hydroxyl radical footprinting of the hmp promoter. A DNA fragment carrying hmp (positions −133 to 27) or nasD (positions −185 to 66) was obtained by PCR by using 32P-end-labled primer and unlabeled primer as described in Materials and Methods. The DNA fragment, labeled at the 5′ end of either the coding or noncoding strand, was incubated with different amounts of ResD (D) (1, 2, and 4 μM), with 4 μM ResE (E), or with both ResD and ResE before hydroxyl radical treatment. The labeled hmp coding strand was also incubated with ResD and ResE in the absence of ATP. The numbers on the left indicate the nucleotide positions relative to the transcriptional start site. Sequence reactions (lanes A, G, C, and T) were carried out by using the labeled primer that was used for PCR. The protected regions indicated by solid lines on the right are separated by approximately 10 bp. The protected region in hmp indicated by a dotted line is separated by approximately 5 bp from the adjacent protected region.

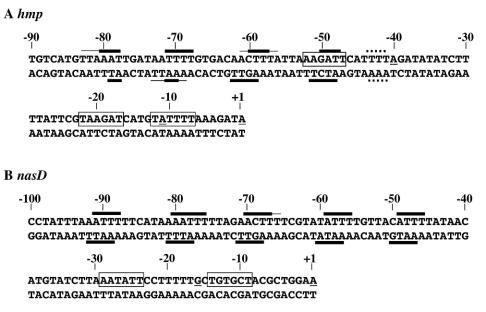

Figure 2 summarizes the results of the hydroxyl radical footprinting experiments. A monomer of the OmpR family of response regulators, such as OmpR and PhoB, binds to DNA that spans approximately 10 bp (9, 19, 21, 26, 37, 40, 54). Taken together, our footprinting results suggest that five ResD monomers bind tandemly to the same face of the DNA helix except at the most promoter-proximal binding site of hmp.

FIG. 2.

ResD binding regions upstream of hmp (A) and nasD (B). The nucleotide sequences of the hmp and nasD regulatory regions relative to the transcription start site are shown for both coding (top) and noncoding (bottom) strands. The thick lines indicate the nucleotides protected from attack by hydroxyl radicals; the thin lines indicate the regions that were partially protected; and the dotted lines indicate the ResD binding regions that are located on different faces of the DNA helix than the rest of the binding regions. Transcription start sites utilized in vitro are underlined, and each −10 sequence is enclosed in a box.

ResD activates in vitro transcription of hmp, nasD, and fnr, and phosphorylation of ResD markedly stimulates transcription.

The hydroxyl radical footprinting experiment and the DNase I footprinting analysis indicated that ResD activates transcription of hmp, nasD, and probably fnr by directly interacting with the promoters. Previous work demonstrated that ctaA transcription in vitro was stimulated by phosphorylated ResD (ResD∼P) (55). It has also been shown that hmp transcription in vitro is activated by ResD∼P, but the question of how phosphorylation affects ResD-dependent transcription was not addressed (53). We wished to determine whether ResD is also sufficient to activate the transcription of anaerobically induced genes for two reasons. First, ResD is needed for both aerobic and anaerobic respiration. Hence, it is possible that to achieve higher gene expression under anaerobic conditions, ResD must be assisted by another coactivator. Alternatively, the stronger induction might be caused by a higher ResD phosphorylation level. Second, a previous gel retardation analysis showed that larger amounts of ResD are required for binding to fnr than for binding to hmp and nasD, and phosphorylation of ResD had no significant stimulatory effect on the binding affinity to fnr, unlike the effect on the binding affinity to hmp and nasD (49). This result could be explained by involvement of another protein that stabilized a complex between ResD and the fnr promoter, leading to activation of transcription. Therefore, we tested these possibilities by examining in vitro runoff transcription of the anaerobically induced promoters using B. subtilis RNAP, ResD, and ResE.

When ResD and ResE were purified by one-step affinity column chromatography as described previously (49), we found that in vitro transcription was activated by ResD but the phosphorylation state of ResD had only a minor effect on stimulation. Therefore we made two modifications to the purification method. First, nucleic acids were removed from the ResD preparation by precipitation with streptomycin sulfate (the absence of contaminated nucleic acids in the purified ResD preparation was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by staining with ethidium bromide). Second, the ResD protein that eluted from the chitin affinity column was further purified by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography (see Materials and Methods). Similarly, ResE was purified by affinity chromatography, followed by purification by Hi-Q column chromatography.

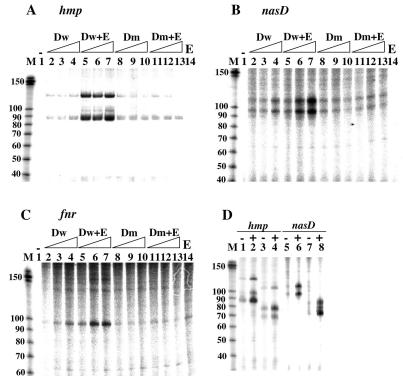

In vitro transcription by using the ResD and ResE proteins prepared by the new purification method showed that phosphorylation markedly affected the activity of ResD; therefore, all experiments described in this paper were carried out with these proteins. In the absence of ResD and ResE, the levels of the transcripts of hmp (Fig. 3A), nasD (Fig. 3B), and fnr (Fig. 3C) were very low or the transcripts were hardly detected (lanes 1). Increased amounts of unphosphorylated ResD slightly stimulated transcription (Fig. 3, lanes 2 to 4). In addition to the transcripts of the expected sizes (86 nucleotides for hmp, 96 nucleotides for nasD, and 101 nucleotides for fnr; note that extra nucleotides in the hmp and fnr transcripts originated from the PCR primers used for amplification of the templates), additional longer transcripts were detected for hmp (126 and 97 nucleotides) and for nasD (112 nucleotides) (the sizes of the transcripts were estimated by sequence ladders, which are not shown in Fig. 3, together with RNA markers). Transcription was greatly stimulated in the presence of ResD and ResE, indicating that phosphorylation of ResD enhances transcription initiation (lanes 5 to 7).

FIG. 3.

(A to C) In vitro transcription analysis of the hmp (A), nasD (B), and fnr (C) promoters. Transcription was carried out with 25 nM purified RNAP and 5 nM template without ResD and ResE (lane 1), with increased amounts of wild-type ResD (Dw) (lanes 2 to 4), with wild-type ResD and ResE (lanes 5 to 7), with the D57A ResD mutant (Dm) (lanes 8 to 10), with the D57A ResD mutant and ResE (lanes 11 to 13), and with only ResE (E) (lane 14). The amounts of ResD and ResE used were 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 μM for hmp transcription and 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μM for nasD and fnr transcription. Equal amounts of ResD and ResE were used, and the highest concentration of ResE was used in the reaction mixture containing only ResE. (D) Transcription analysis of the hmp and nasD promoters with different templates. Transcription was carried out as described above for panels A and B in the absence (−) or in the presence (+) of 0.5 μM ResD and ResE (for hmp) or 1.0 μM ResD and ResE (for nasD). The templates were as follows: lanes 1 and 2, hmp (positions −185 to 79); lanes 3 and 4, hmp (positions −185 to 61); lanes 5 and 6, nasD (positions −138 to 96); and lanes 7 and 8, nasD (positions −138 to 66). The positions of RNA size markers (in nucleotides) are shown in lane M.

Amino acid sequence alignment of ResD with other response regulators suggested that Asp57 is the phosphorylation site. To further examine the effect of ResD phosphorylation on transcription, the aspartate residue was replaced by alanine, and the mutant ResD was overproduced and purified from E. coli as described in Materials and Methods. Transcription was stimulated by the mutant ResD (D57A) protein to a level similar to that stimulated by unphosphorylated wild-type ResD (Fig. 3, compare lanes 2 to 4 and lanes 8 to 10), and the amounts of the transcripts were not further increased in the presence of ResE (lanes 11 to 13). These results demonstrated that ResD alone is sufficient to activate transcription of hmp, nasD, and fnr and that phosphorylation at Asp57 strongly enhances the transcriptional activity of ResD. However, unphosphorylated ResD, both wild type and mutant, can activate transcription, albeit to a lesser extent.

Although hmp transcription and nasD transcription were shown to start in vivo at a single site (29) and two adjacent sites (46), respectively, in vitro transcription also produced longer transcripts, indicating that additional transcription start sites were utilized in vitro. Since the amounts of the longer transcripts were also increased by ResD and by ResD∼P in particular, we examined how these transcripts were generated by using new templates for hmp (positions −185 to 61) and nasD (positions −138 to 65) for in vitro transcription. Each new template has the same upstream end as the other template and a shortened downstream end. If the additional transcription started upstream of the transcription start site utilized in vivo and transcription proceeded in the same direction, hmp transcripts should have been shorter with the new templates (68, 79, and 108 nucleotides instead of 86, 97, and 126 nucleotides). Similarly, the sizes of the nasD transcripts should have been reduced to 71 and 87 nucleotides (again, extra nucleotides were generated from oligonucleotides used to amplify the templates by PCR). If the additional transcription proceeded in the opposite direction by using the complementary strand as a template, the size of the shortest transcript, but not the size of the larger transcript(s), should have been changed. The results shown in Fig. 3D indicate that the sizes of the transcripts corresponded well to the sizes predicted by the first possibility. A sequence similar to the −10 sequence (TATAAT) recognized by σA-RNAP was present upstream of each transcription start site (Fig. 2). These results showed that ResD activated hmp and nasD transcription in vitro at an additional transcription start site(s) in addition to the native transcription start site (see Discussion).

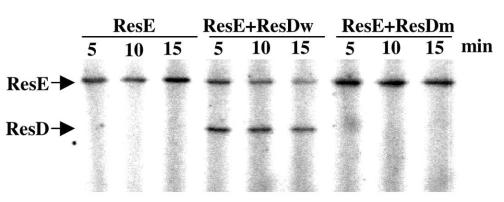

Aspartate 57 of ResD is required for phosphorylation by ResE.

The ResD (D57A) mutant was shown to activate in vitro transcription of hmp, nasD, and fnr. Although the stimulatory effect was much lower than that of phosphorylated ResD, the mutant ResD possessed an activity similar to that of unphosphorylated wild-type ResD to activate the transcription in vitro. One possible reason for this is that ResD has an alternative phosphorylation site. The phosphorylation site mutant (D57N) of the chemotaxis response regulator CheY can be phosphorylated at Ser56 by the CheA sensor kinase (4). However, the amino acid corresponding to Ser56 of CheY is Leu in ResD, and the CheY (D57A) mutant was not phosphorylated at Ser56, suggesting that the alternative phosphorylation of ResD is unlikely. To confirm this, we carried out in vitro phosphorylation of ResD by ResE. Figure 4 shows that wild-type ResD was phosphorylated in the presence of ResE and [γ-32P]ATP, but no phosphorylation was detected in the mutant ResD. This result clearly demonstrated that Asp57 is the phosphorylation residue and that the D57A mutant cannot be phosphorylated by ResE.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation assay of wild-type and mutant ResD. ResE, in the absence and presence of wild-type ResD (ResDw) or the D57A mutant ResD (ResDm), was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP at room temperature for the times indicated. The samples were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel before autoradiography.

Unphosphorylated ResD is able to activate the ResDE regulon in vivo by responding to oxygen limitation.

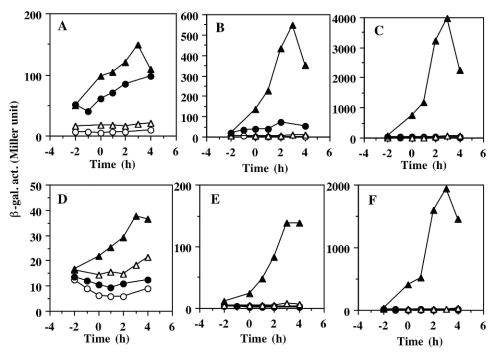

At least in vivo, mutations in resE impair ResD-dependent gene regulation. Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that only phosphorylated ResD can activate transcription of the target genes. However, this conclusion should be carefully drawn because the transcription of resDE from the major resA operon promoter requires ResD and ResE (63). In fact, in vitro experiments described above indicated that unphosphorylated ResD (D57A) is able to activate the transcription of ResDE-dependent genes in vitro to a lesser extent. Therefore, we decided to examine whether the D57A mutant is able to activate transcription in vivo and, if so, whether the activation is still dependent on oxygen limitation. In order to express the resD gene independently of ResDE, the wild-type and mutant resD genes, placed under control of the IPTG-inducible Pspank-hy promoter (10), were introduced into the amyE locus of the resDE mutant strain. Therefore, in the resulting strains, ResE was absent and ResD was produced solely from the IPTG-inducible resD construct. The expression of three lacZ fusions to the fnr, nasD, and hmp promoters was examined in cells grown under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions.

The expression of nasD and hmp in strains carrying the wild-type resD gene was greatly activated by oxygen limitation, and the expression was dependent on IPTG (Fig. 5B and C). In contrast, fnr-lacZ expression was similar in cells grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, indicating that the oxygen-dependent regulation of fnr was largely eliminated by circumventing the autoregulatory pathway of resD expression (Fig. 5A). This may have been due to the lower fnr induction by oxygen limitation relative to nasD and hmp induction, as well as the stimulatory effect under aerobic conditions of increasing amounts of ResD brought about by an oxygen-independent promoter. The expression of nasD-lacZ and hmp-lacZ in cells carrying Pspank-hy resD (D57A) was activated only in the presence of IPTG under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 5E and F), although the expression was two- to fourfold lower than that observed in cells bearing the wild-type resD gene. The latter result suggests that the wild-type ResD may be phosphorylated by a noncognate kinase(s) or by small compounds with high-energy phosphate in the absence of ResE, thus leading to higher gene expression. Apparently, this ResE-independent phosphorylation also responds to oxygen limitation. A more important observation in this experiment is that ResD (D57A) was able to activate the ResDE regulon in response to oxygen limitation. This result, together with the in vitro transcription results described here, clearly demonstrated that ResD, without phosphorylation, is able to respond to the redox state of cells and to activate transcription.

FIG. 5.

Expression of fnr-lacZ, nasD-lacZ, and hmp-lacZ in cells grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. ΔresDE strains carrying fnr-lacZ (A and D), nasD-lacZ (B and E), and hmp-lacZ (C and F) were grown in 2× YT supplemented with 1% glucose and 0.2% potassium nitrate and in the absence or presence of IPTG. The strains carried IPTG-inducible wild-type resD (A to C) or mutant resD (D57A) (D to E) at the amyE locus. Symbols: ○, aerobic growth in the absence of IPTG; •, aerobic growth in the presence of 1 mM IPTG; ▵, anaerobic growth in the absence of IPTG: ▴, anaerobic growth in the presence of 1 mM IPTG. Time zero was the end of the exponential growth phase. β-gal. act., β-galactosidase activity.

DISCUSSION

In this study we examined both in vivo and in vitro how the response regulator ResD activates the transcription of genes that function in nitrate respiration under oxygen limitation conditions. Previous DNase I footprinting studies demonstrated that ResD binds to the promoter regions of hmp, nasD, and fnr, as well as ctaA, which suggests that ResD directly activates transcription of these genes (49, 69). Hydroxyl radical footprinting experiments described here revealed that ResD binds tandemly to the same face of the DNA helix at the nasD promoter. OmpR is also known to bind to the same face of the DNA helix as a head-to-tail dimer, with each monomer occupying 10 bp of DNA (18, 19, 21). OmpR is unable to form a stable complex with DNA as a monomer (18, 21). Similarly, several monomers of PhoB bind head to tail to successive 11-base direct repeats in the target DNA (9, 37, 54). The ugpB promoter has 3.5 pho boxes, and in vitro analysis showed that PhoB binds to the pho half site, although deletion of the half site did not affect the expression of ugp in vivo (25). Therefore, unlike OmpR, PhoB is able to bind DNA as a monomer. Our results also showed that ResD is likely to bind as a monomer to 10-bp regions of the target DNA. The most proximal ResD binding site of hmp is situated on a different helix face of the DNA than the rest of the binding sites. At present, it is not known how this unusual pattern of binding sites in hmp affects transcriptional activation of hmp by ResD. The hydroxyl radical footprinting analysis, together with sequence comparisons, did not provide any solid consensus sequence data for ResD except that the A(A/T)TT sequence is commonly protected.

Our in vitro transcription experiment indicated that ResD is required and sufficient to activate transcription of the anaerobically induced genes. The extent of the stimulation by phosphorylation of ResD varies depending on the target gene. Phosphorylation had the most drastic stimulatory effect on hmp transcription, had a slightly smaller effect on nasD transcription, and had the least effect on fnr transcription, which corresponds well to the level of in vivo activation of each gene observed upon oxygen limitation. Additional transcription start sites detected in hmp and nasD are likely artifacts only seen in vitro. One possible reason for this is that some transcription initiates when less than five ResD monomers bind to the regulatory region and the most upstream or most downstream ResD interacts with RNAP. Alternatively but not mutually exclusively, if the αCTD of RNAP interacts with ResD, the linker of the α subunit, which connects the N-terminal and C-terminal domains, allows flexible contact between RNAP and ResD. A previous study showed that the α subunit is flexible enough to allow the CTD to move freely at least 30 bp along the promoter (45). This suggests that ResD interacts with αCTD to activate transcription. Several lines of circumstantial evidence support this possibility. First, OmpR, which is known to interact with the αCTD, binds to a region at positions −107 to −39 of ompF, and PhoB binds to a region at positions −63 to −20 of pstS, closer to the promoter. Our footprinting data indicated that ResD binds to the region between positions −41 and −83 of hmp and to the region between positions −46 and −92 of nasD. Second, the ctaA gene was transcribed from two promoters utilized by σA and σE holo-RNAP, and transcription from both was shown to be stimulated by ResD∼P in vitro (55). These results support the hypothesis that there is probably an interaction between ResD and α but not between ResD and σ. Third, ResDE-dependent transcription of hmp was shown to be inhibited by Spx, a newly discovered anti-α factor (53). Last, we have isolated certain amino acid substitutions of the αCTD which affect ResDE-dependent gene regulation (unpublished data). It remains to be determined whether ResD interacts with αCTD and which step of transcription initiation is controlled by ResD.

Phosphorylation of the N-terminal aspartate has been shown to be the key step in two-component regulatory pathways. Structural analyses of the receiver domains of response regulators have revealed a conformational change involving displacement of β strands 4 and 5, as well as α helices 3 and 4, away from the active site (8, 13, 27, 31-33). These structural rearrangements in the receiver domain result in changes that affect the activity of output domains, including dimer-multimer formation (5, 17, 24, 34, 56), and/or that relieve the inhibitory effect by the receiver domain (3, 6, 15, 16, 23, 37, 66, 68). Regardless of the mechanism by which phosphorylation affects the output activity, most of response regulators are active in vivo in phosphorylated forms, as shown by the finding that mutations in the cognate kinase gene impair or greatly reduce target gene expression. Some, although not many, exceptions have been reported. The B. subtilis DegU regulator required for production of degradative enzymes and competence development has been shown to function as either a phosphorylated form or an unphosphorylated form depending on the target gene (for a review see reference 44). The conserved aspartate residue is not essential for the activity of BldM, a response regulator involved in the developmental cycle of Streptomyces coelicolor (43).

Our finding that the ResD (D57A) mutant retains the ability to respond to oxygen limitation is unexpected but interesting because, unlike phosphorylated and unphosphorylated DegU, phosphorylated ResD and unphosphorylated ResD activate the same target genes. E. coli UhpA, a response regulator involved in sugar phosphate transport, also has phosphorylation-independent activity. However, in this case UhpA carrying a substitution of phosphorylated Asp54 with Asn has constitutive activity only when it is overproduced (66). To our knowledge, this is the first example of a response regulator that is activated by a phosphorylation-independent mechanism and yet responds to the same conditions that are sensed by the cognate sensor kinase. Many unphosphorylated response regulators have been shown to activate transcription in vitro; however, this phenomenon was brought in to question by the recent finding that purified Spo0A from E. coli is already phosphorylated (30). This may explain why the unphosphorylated response regulator PrrA has more activity in vitro than the protein with the phosphorylation site mutation (14). In contrast, our results showed that unphosphorylated ResD and the mutant ResD have similar activities for in vitro transcription. Furthermore, compelling evidence that unphosphorylated ResD activates transcription of the target genes was obtained by the in vivo study performed with strains carrying the mutant ResD. At this time we cannot completely eliminate the possibility that a coactivator, which binds tightly to ResD, is responsible for redox sensing. In future studies we will focus on determining whether ResD itself responds to oxygen limitation and, if so, how the redox-related signal is sensed by ResD to activate transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Kenney and Peter Zuber for valuable discussions and Peter Zuber for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Marion Hulett and David Rudner for gifts of strain MH5633 and plasmid pDR111, respectively.

This work was supported by grant MCB0110513 from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., N. Kato, M. Tsuzuki, and T. Mizuno. 1994. Mechanism of gene activation by the Escherichia coli positive regulator, OmpR: a mutant defective in transcriptional activation. FEBS Lett. 351:303-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba, H., F. Nakasai, S. Mizushima, and T. Mizuno. 1989. Phosphorylation of a bacterial activator protein, OmpR, by a protein kinase, EnvZ, results in stimulation of its DNA-binding ability. J. Biochem. 106:5-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, M. P., K. B. Zumbrennen, and W. R. McCleary. 2001. Genetic evidence that the α5 helix of the receiver domain of PhoB is involved in interdomain interactions. J. Bacteriol. 183:2204-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appleby, J. L., and R. B. Bourret. 1999. Activation of CheY mutant D57N by phosphorylation at an alternative site, Ser-56. Mol. Microbiol. 34:915-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asayama, M., K. Saito, and Y. Kobayashi. 1998. Translational attenuation of the Bacillus subtilis spo0B cistron by an RNA structure encompassing the initiation region. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:824-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baikalov, I., I. Schröder, M. Kaczor-Grzeskowiak, D. Cascio, R. P. Gunsalus, and R. E. Dickerson. 1998. NarL dimerization? Suggestive evidence from a new crystal form. Biochemistry 37:3665-3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birck, C., Y. Chen, F. M. Hulett, and J. P. Samama. 2003. The crystal structure of the phosphorylation domain in PhoP reveals a functional tandem association mediated by an asymmetric interface. J. Bacteriol. 185:254-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birck, C., L. Mourey, P. Gouet, B. Fabry, J. Schumacher, P. Rousseau, D. Kahn, and J. P. Samama. 1999. Conformational changes induced by phosphorylation of the FixJ receiver domain. Structure 7:1505-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco, A. G., M. Sola, F. X. Gomis-Ruth, and M. Coll. 2002. Tandem DNA recognition by PhoB, a two-component signal transduction transcriptional activator. Structure 10:701-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britton, R. A., P. Eichenberger, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, P. Fawcett, R. Monson, R. Losick, and A. D. Grossman. 2002. Genome-wide analysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor (sigma-H) regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:4881-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckler, D. R., Y. Zhou, and A. M. Stock. 2002. Evidence of intradomain and interdomain flexibility in an OmpR/PhoB homolog from Thermotoga maritima. Structure 10:153-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Y., C. Birck, J. P. Samama, and F. M. Hulett. 2003. Residue R113 is essential for PhoP dimerization and function: a residue buried in the asymmetric PhoP dimer interface determined in the PhoPN three-dimensional crystal structure. J. Bacteriol. 185:262-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho, H. S., S. Y. Lee, D. Yan, X. Pan, J. S. Parkinson, S. Kustu, D. E. Wemmer, and J. G. Pelton. 2000. NMR structure of activated CheY. J. Mol. Biol. 297:543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comolli, J. C., A. J. Carl, C. Hall, and T. Donohue. 2002. Transcriptional activation of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene P2 promoter by the response regulator PrrA. J. Bacteriol. 184:390-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Da Re, S., J. Schumacher, P. Rousseau, J. Fourment, C. Ebel, and D. Kahn. 1999. Phosphorylation-induced dimerization of the FixJ receiver domain. Mol. Microbiol. 34:504-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellison, D. W., and W. R. McCleary. 2000. The unphosphorylated receiver domain of PhoB silences the activity of its output domain. J. Bacteriol. 182:6592-6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiedler, U., and V. Weiss. 1995. A common switch in activation of the response regulators NtrC and PhoB: phosphorylation induces dimerization of the receiver modules. EMBO. J. 14:3696-3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harlocker, S. L., L. Bergstrom, and M. Inouye. 1995. Tandem binding of six OmpR proteins to the ompF upstream regulatory sequences of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26849-26856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison-McMonagle, P., N. Denissova, E. Martinez-Hackert, R. H. Ebright, and A. M. Stock. 1999. Orientation of OmpR monomers within an OmpR:DNA complex determined by DNA affinity cleaving. J. Mol. Biol. 285:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Head, C. G., A. Tardy, and L. J. Kenney. 1998. Relative binding affinities of OmpR and OmpR-phosphate at the ompF and ompC regulatory sites. J. Mol. Biol. 281:857-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, K. J., and M. M. Igo. 1996. Identification of the bases in the ompF regulatory region, which interact with the transcription factor OmpR. J. Mol. Biol. 262:615-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulett, F. M. 2001. The pho regulon, p. 193-201. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Ireton, K., D. Z. Rudner, K. J. Siranosian, and A. D. Grossman. 1993. Integration of multiple developmental signals in Bacillus subtilis through the Spo0A transcription factor. Genes Dev. 7:283-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeon, Y., Y. S. Lee, J. S. Han, J. B. Kim, and D. S. Hwang. 2001. Multimerization of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated ArcA is necessary for the response regulator function of the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40873-40879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasahara, M., K. Makino, M. Amemura, A. Nakata, and H. Shinagawa. 1991. Dual regulation of the ugp operon by phosphate and carbon starvation at two interspaced promoters. J. Bacteriol. 173:549-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenney, L. J. 2002. Structure/function relationships in OmpR and other winged-helix transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kern, D., B. F. Volkman, P. Luginbuhl, M. J. Nohaile, S. Kustu, and D. E. Wemmer. 1999. Structure of a transiently phosphorylated switch in bacterial signal transduction. Nature 402:894-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo, H., A. Nakagawa, J. Nishihira, Y. Nishimura, T. Mizuno, and I. Tanaka. 1997. Escherichia coli positive regulator OmpR has a large loop structure at the putative RNA polymerase interaction site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:28-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaCelle, M., M. Kumano, K. Kurita, K. Yamane, P. Zuber, and M. M. Nakano. 1996. Oxygen-controlled regulation of flavohemoglobin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3803-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ladds, J. C., K. Muchova, D. Blaskovic, R. J. Lewis, J. A. Brannigan, A. J. Wilkinson, and I. Barak. 2003. The response regulator Spo0A from Bacillus subtilis is efficiently phosphorylated in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 223:153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, S. Y., H. S. Cho, J. G. Pelton, D. Yan, R. K. Henderson, D. S. King, L. Huang, S. Kustu, E. A. Berry, and D. E. Wemmer. 2001. Crystal structure of an activated response regulator bound to its target. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:52-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis, R. J., J. A. Brannigan, K. Muchova, I. Barak, and A. J. Wilkinson. 1999. Phosphorylated aspartate in the structure of a response regulator protein. J. Mol. Biol. 294:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis, R. J., K. Muchova, J. A. Brannigan, I. Barak, G. Leonard, and A. J. Wilkinson. 2000. Domain swapping in the sporulation response regulator Spo0A. J. Mol. Biol. 297:757-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis, R. J., D. J. Scott, J. A. Brannigan, J. C. Ladds, M. A. Cervin, G. B. Spiegelman, J. G. Hoggett, I. Barak, and A. J. Wilkinson. 2002. Dimer formation and transcription activation in the sporulation response regulator Spo0A. J. Mol. Biol. 316:235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, J., and P. Zuber. 2000. The ClpX protein of Bacillus subtilis indirectly influences RNA polymerase holoenzyme composition and directly stimulates sigma-dependent transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:885-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, W., and F. M. Hulett. 1997. Bacillus subtilis PhoP binds to the phoB tandem promoter exclusively within the phosphate starvation-inducible promoter. J. Bacteriol. 179:6302-6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino, K., M. Amemura, T. Kawamoto, S. Kimura, H. Shinagawa, A. Nakata, and M. Suzuki. 1996. DNA binding of PhoB and its interaction with RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 259:15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makino, K., M. Amemura, S. K. Kim, A. Nakata, and H. Shinagawa. 1993. Role of the sigma 70 subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation by activator protein PhoB in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 7:149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure 5:109-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 269:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattison, K., R. Oropeza, and L. J. Kenney. 2002. The linker region plays an important role in the interdomain communication of the response regulator OmpR. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32714-32721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 43.Molle, V., and M. J. Buttner. 2000. Different alleles of the response regulator gene bldM arrest Streptomyces coelicolor development at distinct stages. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1265-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Msadek, T., F. Kunst, and G. Rapoport. 1995. A signal transduction network in Bacillus subtilis includes the DegS/DegU and ComP/ComA two-component systems, p. 447-471. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 45.Murakami, K., J. T. Owens, T. Belyaeva, C. F. Meares, S. J. W. Busby, and A. Ishihama. 1997. Positioning of two alpha subunit carboxy-terminal domains of RNA polymerase at promoters by two transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94:11274-11278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakano, M. M., T. Hoffmann, Y. Zhu, and D. Jahn. 1998. Nitrogen and oxygen regulation of Bacillus subtilis nasDEF encoding NADH-dependent nitrite reductase by TnrA and ResDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:5344-5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakano, M. M., M. A. Marahiel, and P. Zuber. 1988. Identification of a genetic locus required for biosynthesis of the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 170:5662-5668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakano, M. M., F. Yang, P. Hardin, and P. Zuber. 1995. Nitrogen regulation of nasA and the nasB operon, which encode genes required for nitrate assimilation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:573-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakano, M. M., Y. Zhu, M. LaCelle, X. Zhang, and F. M. Hulett. 2000. Interaction of ResD with regulatory regions of anaerobically induced genes in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1198-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 1998. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:165-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 2001. Anaerobiosis, p. 393-404. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 52.Nakano, M. M., P. Zuber, P. Glaser, A. Danchin, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3796-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakano, S., M. M. Nakano, Y. Zhang, M. Leelakriangsak, and P. Zuber. 2003. A regulatory protein that interferes with activator-stimulated transcription in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100:4233-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okamura, H., S. Hanaoka, A. Nagadoi, K. Makino, and Y. Nishimura. 2000. Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J. Mol. Biol. 295:1225-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paul, S., X. Zhang, and F. M. Hulett. 2001. Two ResD-controlled promoters regulate ctaA expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:3237-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porter, S. C., A. K. North, A. B. Wedel, and S. Kustu. 1993. Oligomerization of NTRC at the glnA enhancer is required for transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 7:2258-2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pratt, L. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1994. OmpR mutants specifically defective for transcriptional activation. J. Mol. Biol. 243:579-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qi, Y., and M. Hulett. 1998. PhoP-P and RNA polymerase σA holoenzyme are sufficient for transcription of Pho regulon promoters in Bacillus subtilis: Pho-P activator sites within the coding region stimulate transcription in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1187-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson, V. L., T. Wu, and A. M. Stock. 2003. Structural analysis of the domain interface in DrrB, a response regulator of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. J. Bacteriol. 185:4186-4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slauch, J. M., F. D. Russo, and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. Suppressor mutations in rpoA suggest that OmpR controls transcription by direct interaction with the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 173:7501-7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sola, M., F. X. Gomis-Ruth, L. Serrano, A. Gonzalez, and M. Coll. 1999. Three-dimensional crystal structure of the transcription factor PhoB receiver domain. J. Mol. Biol. 285:675-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun, G., E. Sharkova, R. Chesnut, S. Birkey, M. F. Duggan, A. Sorokin, P. Pujic, S. D. Ehrlich, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1374-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsuzuki, M., H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 1994. Gene activation by the Escherichia coli positive regulator, OmpR. Phosphorylation-independent mechanism of activation by an OmpR mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 242:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walthers, D., V. K. Tran, and L. J. Kenney. 2003. Interdomain linkers of homologous response regulators determine their mechanism of action. J. Bacteriol. 185:317-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webber, C. A., and R. J. Kadner. 1997. Involvement of the amino-terminal phosphorylation module of UhpA in activation of uhpT transcription in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1039-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zaychikov, E., P. Schickor, L. Denissova, and H. Heumann. 2001. Hydroxyl radical footprinting. Methods Mol. Biol. 148:49-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang, J. H., G. Xiao, R. P. Gunsalus, and W. L. Hubbell. 2003. Phosphorylation triggers domain separation in the DNA binding response regulator NarL. Biochemistry 42:2552-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang, X., and F. M. Hulett. 2000. ResD signal transduction regulator of aerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis: cta promoter regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1208-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]