Abstract

End-of-life decision making is a complex phenomenon and providers, patients, and families often have different views about the appropriateness of treatment choices. The results presented here are part of a larger grounded-theory study of reconciling decisions near the end of life. In particular, we examined how providers (N=15) worked near the end of patients′ lives toward changing the treatment decisions of patients and families from those decisions that providers described as unrealistic (i.e., curative) to those that providers described as more realistic (i.e., palliative). According to providers, shifting patients′ and families′ choices from curative to palliative was usually accomplished by changing patients′ and families′ understanding of the patient's overall “big picture” to one that was consistent with the providers′ understanding. Until patients and families shifted their understanding of the patient's condition—the big picture—they continued to make what providers judged as unrealistic treatment choices based on an inaccurate understanding of what was really going on. These unrealistic choices often precluded possibilities for a “good death.” According to providers, the purpose of attempting to shift the patient or proxy's goals was that realistic goals lead to realistic palliative treatment choices that providers associated with a good death. In this article we review strategies used by providers when they believed a patient's death was imminent to attempt to shift patients′ and families′ understandings of the big picture, thus ultimately shifting their treatment decisions.

Keywords: end-of-life, decision making, death, grounded theory

As technology advances, patients, families, and providers face increasingly complex issues regarding end-of-life decision making. Over the past several decades many patients and their families have demanded increased control over and participation in decision making at the end of life. A patient's right to self-determination is the moral underpinning of these demands. However, patient self-determination in practice is complex. Advance directives (AD) were thought of as one way for patients to ensure their wishes would be followed in the event the patient was no longer able to participate in decision making. Nevertheless, decision making near the end of life often is still regarded as problematic even with advance directives. There are discrepancies between the treatments patients receive and those they had indicated they preferred via AD, usually with patients receiving more curative or aggressive types of treatment than desired (Connors et al., 1995; Teno, Licks et al., 1997; Teno, Lynn et al., 1997).

Concerns about the level of treatment received are not unique to patients and families. In a survey of physicians (n=687) and nurses (n=759), Solomon et al. (1993) reported that 78% of house staff and 58% of attending physicians reported sometimes offering treatments that were overly burdensome to their patients. Most providers were more concerned about overtreatment than undertreatment.

Based on the results of a grounded-theory study of intensive care unit nurses, house staff, and attendings (n=21), Simmonds (1996) reported that all providers interviewed agreed that extreme treatment or overtreatment often occurred in the intensive care unit. The providers identified fears of litigation and the unrealistic expectations of family members as the main reasons for overtreatment. Providers also did not “blame families entirely for their unrealistic expectations” (Simmonds, p. 171), citing unrealistic providers and unclear communication between providers and families regarding the implications of treatment decisions as part of the reason families chose more aggressive treatment.

Other researchers examining the relationship-between seriously ill cancer patients' predictions of their own prognosis and their treatment preferences found that patients' beliefs about prognoses were associated with their treatment choices (Weeks et al., 1998). Patients were more optimistic about their 6-month survival than their physicians and were more likely to choose life-extending therapy over comfort care. The researchers suggested that enhanced communication between physicians and patients about prognosis would improve clinical care.

The need for improved communication among providers, patients, and families near the end of life of a patient is a common finding of several studies (Norton & Talerico, 2000; Tilden, Tolle, Garland, & Nelson, 1995; Wilson & Daley, 1999). Problems with communication regarding end-of-life decision making include lack of information, lack of access to providers, and lack of family inclusion in the process of decision making (Kayser-Jones, 1995). Problems with communication may make it difficult for patients or families to make informed choices and for providers to honor patients' wishes.

Few researchers have explored how patienttreatment decisions change over the course of an illness or how patients, families, and providers achieve agreement on treatment decisions. Tilden, Tolle, Nelson, Thompson, & Eggman (1999) described four typical phases that surrogate decision makers go through when coming to a decision to withdraw life support for their loved one: recognizing futility; coming to terms; shouldering the surrogate role; and facing the withdrawal question. Based on data from a 14-site participant observation study, Degner and Beaton (1987) described four patterns of control over the decision-making process: provider, patient, family, and jointly controlled. In provider and jointly controlled decision making, providers used both formal and informal strategies designed to influence patients' or proxies' decisions near the end of life.

More recently, Markson et al. (1997) reported that the vast majority (91%) of 653 physicians surveyed would attempt to persuade a patient to change a decision assessed to be ill-informed, and most (88%) would attempt to persuade a patient to change a decision seen by providers as medically unreasonable or in conflict with that patient's best interest.

Several researchers have examined how providers attempt to persuade the patient (Kayser-Jones, 1995; Sullivan, Hebert, Logan, O'Connor, & McNeely, 1996; Zussman, 1992). One group of researchers described how physician providers (n=14) attempted to frame the decisions regarding mechanical ventilation and intubation to patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). All but one physician admitted to framing information presented to patients in such away as to influence the patient's choice (Sullivan et al.).

The purpose of this study was to develop a grounded theory of how decisions were negotiated among providers and family members near the end of a patient's life. During the development of the theory, Reconciling Decisions Near the End of Life, identification was made of several strategies providers used to assist patients and families to shift from curative to palliative treatment choices and goals. These strategies are the focus of this article.

Method

Following institutional review board approval, provider participants were recruited via a letter of invitation (which received a 60% positive response rate), and family members were recruited via church bulletins. The sample consisted of 20 participants (10 nurses, 5 physicians, and 5 family members) from a midsize Midwestern city. Only data from the nurse and physician participants are presented in this article. Of the 15 providers, 12 were women and 3 were men (see Table 1 for additional characteristics of the provider sample).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Practice Area | Health Care Experience (M) | Health Care Experience (SD) | Health Care Experience (range) | Registered Nurse Providers | Physician Providers | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home health and family practice | 12.00 years | 8.25 | 3–24 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Oncology | 11.60 years | 6.84 | 2–20 years | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Intensive care | 15.75 years | 8.42 | 6–25 years | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Totals | 12.87 years | 7.49 | 3–25 years | 10 | 5 | 15 |

A grounded-theory research design was used for this study (Glaser, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987). There were 18 provider interviews. Each provider was interviewed once; three providers were interviewed a second time to facilitate member checks. All interviews, which were conducted at a time and place of participant convenience, were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The first four interviews were conducted using open-ended questions and lasted 60–90 min. Later interviews lasted 30–60 min, with questions becoming increasingly focused on the evolving categories as data analysis progressed (see Table 2 for examples of early and later interview questions).

Table 2.

Examples of Provider Interview Questions

|

Consistent with a grounded theory research design, data were analyzed using open coding, constant comparative analysis, and axial coding (Glaser, 1992; Strauss, 1987). Dimensional analysis was used as an adjunct data analysis tool. Dimensional analysis is a systematic inquiry into the “parts, attributes, interconnections, context, processes, and implications” of a phenomenon (Schatzman, 1991, p. 309). Following each interview, extensive analysis was done, theoretical questions were raised, and questions were developed for subsequent interviews.

Analysis of the first three interviews (all nurses) revealed that they engaged in a host of strategies that were directed at assessing how patients understand their situations. This included assessing whether the patient's understanding was similar to that of the health care provider (e.g., whether it was “realistic” from the provider's perspective) and whether decisions patients made seemed “reasonable” from the nurses' perspectives. Analysis of these initial interviews also revealed that providers engaged in a host of strategies aimed at assisting patients in coming to a more realistic understanding of their situations and in making more reasonable decisions. Although these strategies could be viewed as paternalistic, they also offered an opportunity to explore these issues in greater depth. Subsequent interviews were designed to gain an understanding of what the providers were doing, what was directing their assessments as well as their efforts to alter patient perceptions, and whether these strategies changed over time.

Deliberate theoretical sampling of providers who did and did not engage in these strategies was not possible because there was no way to make this distinction before interviewing. Therefore, theoretical sampling was built into the design of the interviews. This was accomplished by adding questions to the interviews that would identify whether the provider participant engaged in such assessments and perspective-altering strategies and would explore how they understood these actions and what they were trying to accomplish.

Common to all those who described such strategies was a goal of either preventing a “bad death” or hoping to achieve a “good death.” Providers who were concerned about how realistic the patient's understanding was described the relationship between the patient's understanding, the decisions that resulted from that understanding, and the consequences of those decisions for the quality of their death.

This analysis raised the question of what these providers actually meant by the good death that they were trying to achieve and the bad death they were trying to avoid. Interview questions were altered to enhance understanding of these notions and to understand the relationship between being realistic and these two possible outcomes. Analysis of the subsequent interviews (as well as reanalyzing previous interviews) revealed that these providers had experiences with patients whose unrealistic understandings led to burdensome treatment decisions and thus to deaths with unnecessary pain, suffering, overly aggressive treatment, and unresolved family issues. At this point a theoretical decision was made to pursue an understanding of the processes of shifting goals and treatment decisions.

Subsequent theoretical sampling was designed to discover whether any predictable or patterned differences existed among provider types (e.g., nurses and physicians), work settings (e.g., acute or home care), and work experience (e.g., experienced or novice). It was hypothesized that these might explain which providers or what conditions were likely to result in a provider engaging in strategies to achieve a good death or avoid a bad one and which were not. Further exploration of this relationship in subsequent interviews suggested that experience with dying patients was common to providers who were concerned about and organized their strategies around quality of death. Experience itself, however, did not necessarily lead to such an approach. Additional theoretical sampling was done in order to provide some comparisons around length of experience as a health care provider and, in particular, with patients who were dying.

Several procedures were integrated into the methodological design of this study to maximize the credibility of the results (Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Strauss, 1987). All interviews were transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy, and entered into a computer software program designed to assist qualitative data management (QSR NUD*IST 4, 1997). Memos and matrices were used to track the evolving theory and the methodological choices made by the researcher during the study. The principal researcher met weekly with a multi-disciplinary grounded theory dimensional analysis group. The researcher was engaged in data collection and analysis for 22 months, but the majority of the data was collected during the first 16 months. Analysis and member checks continued until the study was completed. Member checks were ongoing throughout the study and included second interviews with three provider participants (chosen for the breadth and depth of their experience), fieldwork, and interactive presentations of findings to small groups of providers similar to those who participated.

Results

This section begins with a brief synopsis of the grounded theory of reconciling decisions near the end of life (Norton, 1999), which provides the context that grounded the provider strategies to shift patients from curative to palliative treatment decisions.

Reconciling Decisions Near the End of Life

Health care providers often described knowing a patient's death was imminent before the patient or family knew. When these providers believed a patient's death was near, they shifted the purpose of their interventions toward helping the patient achieve a good death. With that in mind, providers worked toward changing patients' and families' treatment decisions from what providers believed were unrealistic curative choices to more realistic palliative choices. In this context, unrealistic decisions were those intended to cure, and realistic decisions were those intended solely to palliate symptoms or to forego curative treatments.

Providers reported that when patients or families continued to make unrealistic (curative) treatment decisions near the end of life, the patient would probably not experience a good death, possibly even having a bad one. A good death was characterized by all providers in a similar way as one that includes time to resolve personal business, time to reconnect with family, time to forgive and be forgiven, time to achieve important goals, and time to say goodbye to loved ones, while maintaining good pain and symptom control. A difficult or bad death was characterized by not being able to say good-bye; having unfinished business, unresolved conflict and anger, and difficulty grieving; undergoing futile treatment, creating bad memories for the family; and having poor symptom and pain control.

According to providers, changing the patient's or proxy's understanding, that is, their “big picture,” to one in accord with the providers' assessment led the patient and family to realistic goals and thus to palliative treatment choices. From the providers' perspective, the big picture was a gestalt of the patient's condition constructed from information about the diagnosis, test results, prognosis, general assessment findings (including physical, emotional, and spiritual factors), treatment options, treatment efficacy, treatment burdens, and patient goals. This information, filtered through providers' knowledge, insights, and experience, formed providers' overall picture of what was going on with the patient. In this context it was the big picture, as perceived by providers, that determined whether goals and treatment decisions were realistic.

Providers expressed a belief that understanding the big picture would probably lead to realistic decisions that in turn would lead to a good death. On the other hand, lack of understanding or acceptance of the big picture increased the likelihood of making unrealistic treatment decisions that would result in unnecessary pain and suffering and in missed opportunities for a good death (e.g., not being able to say good-bye to loved ones). Providers often imputed a lack of understanding and/or acceptance of the overall big picture as the cause of patients' or proxies' adherence to unrealistic goals. Unrealistic goals were goals that the patients could not achieve and/or that led to burdensome aggressive treatments that made it difficult, if not impossible, for patients to achieve a good death. One provider described a dying patient who wanted to continue chemotherapy:

I think like even 2 days before she died she said to me, “When do you think I can go back to teaching?” I just wanted to yell, “Your whole body is full of cancer, and you need to… tie up loose ends!”

This patient was described as having an angry and bitter death. The provider was frustrated by the patient's unwillingness to accept a realistic big picture and her continued adherence to curative treatment decisions. It is the provider big picture that providers said must be shared by patients and family members in order for them to make realistic decisions. Therefore, changing the patient's big picture became the focus of provider interactions.

Providers′ Response to Unrealistic Treatment Decisions

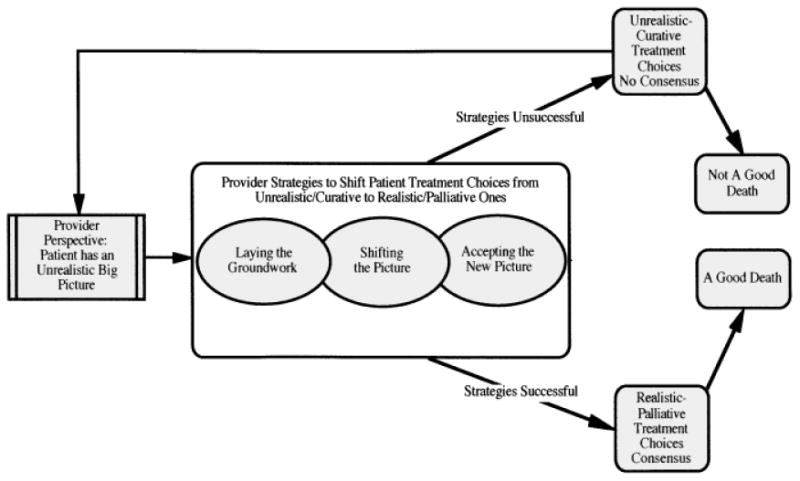

Providers responded differently to perceived unrealistic patient or proxy goals. These responses included: (a) avoiding interactions with the patient and family, (b) referring the patient and family to another provider, and (c) using strategies aimed at shifting patients' unrealistic goals and treatment decisions to more realistic ones. Providers' often responded to unrealistic patient or proxy goals and decisions by using strategies to shift the patient or family picture, and to increase their understanding of what was happening. Early on these strategies were intended to “lay the groundwork” for a new picture. Laying the groundwork was typically followed by strategies focused on shifting the patient or family to a new picture. Finally, once a patient had shifted to a new, more realistic picture, provider strategies focused on helping the patient and the patient's family to accept and keep that realistic picture. Once a patient and family accepted a new picture, their treatment decisions were most likely to be palliative and thus more likely to ultimately result in a good death (Fig. 1). The individual strategies presented in the following sections are grouped under general purposes. However, most strategies were used for more than one purpose (e.g., teaching could be used to lay the groundwork, to shift the understanding of a patient or family toward the patient's picture, and/or to help the patient or family accept a new picture).

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of providers strategies to shift patients from curative to palliative treatment choices.

Laying the Groundwork

Providers routinely used such terms as “laying the groundwork,” “getting them ready,” and “setting the stage” to describe the importance of establishing trust, rapport, and a fundamental knowledge base with patients and their families, especially when a patient has a life-threatening illness. One physician described how he worked with newly diagnosed cancer patients: “When I am first meeting a patient, I'm trying to lay the groundwork about what is going on with their disease.” Laying the groundwork was important because it helped a patient and the patient's family have the background necessary to make realistic palliative treatment decisions should that patient's condition become terminal, and it provided a context to build on throughout the trajectory of the patient's illness. Laying the groundwork was primarily accomplished through strategies such as teaching and planting seeds, a provider strategy of introducing the idea of death to a patient or family.

Teaching

Teaching patients and families, especially about prognosis and treatment choices, was a routinely used intervention that served a multitude of purposes. Teaching played a central role in helping patients shift to a new understanding and acceptance of their big picture. Starting with laying the groundwork, this strategy was pervasive. Providers first used teaching to begin building a picture of a patient's illness and the options for treatment. Providers also described teaching as a mechanism to establish trust and rapport with patients and families. Most providers in this study found it preferable to teach the patient and family over the course of several visits, starting during the initial contact. One provider noted that teaching begins to paint a new, “more accurate understanding” of the picture for the patient. Another noted that teaching the “biology” of the disease helped patients “understand the basics,” which made it easier for providers to shift the patient and family to new understandings and to discussions about palliative-care treatment options should the patient's condition worsen. This strategy was the main way the groundwork was laid for future discussions.

Planting seeds

Another way of laying the groundwork for future discussions was “planting seeds.” Planting seeds entailed beginning to help the patient and family understand the possibility that the patient might not survive. One nurse described this as “opening up” the families for future discussions of palliative care. Another nurse, describing working with patients' with life-threatening illnesses and their families, noted:

They [the patients] may not survive no matter what we do, and we need to help them [patient and family] entertain that, and plant the seed. And sometimes you plant the seed, you back off, and then you revisit it a little bit at a time, you know, each day.

According to some providers, if death is not explicitly introduced, it may not be seen by the patient or family as within the realm of possibility, even when providers view imminent death as obvious. In contrast, introducing the possibility of death early makes it easier for patients or their loved ones to accept bad news if the patient's condition deteriorates later.

Shifting the Picture

In order for treatment choices to be shifted from unrealistic curative ones to realistic palliative ones, the patient or proxy decision maker must give up an old understanding of what is going on and develop a new understanding to replace it. Providers had several terms to describe this, such as: “refocusing,” “re-framing,” “getting the patient on the same page,” and “painting a new picture.” Some providers described summarizing and creating a new context for patients' health care events. For example, this might include reframing a patient's or family's understanding of particular health events, from an exacerbation of a chronic illness to those indicative of imminent death. One nurse described how she framed end-of-life discussions:

And usually it is a review of what has happened in the last 6 months, and how she has not been eating, and she has been losing weight, and she hasn't known the grandkids when they have come to see her. She hasn't been herself.

Although the family had all of the individual pieces of information (e.g., weight loss, changes in cognition), the provider reinterpreted the information and created a new picture for the family from one of chronic illness to one of impending death. The provider then described treatment options: “We can treat her with antibiotics, and we can prolong her life, but are we really helping her? Is it what she would want?” Providers used several strategies in an attempt to shift decision makers' understanding to a new and more accurate picture (e.g., a picture in accord with the health care providers) that would be likely to result in the patient or family making more realistic choices. Shifting the picture included such strategies as working together, family meetings, creating new expectations, changing the scope of choice, and changing the value of treatment options. In this phase of transition, timing and collaboration among providers became paramount.

Working together

“Working together,” “working in concert,” “keeping everyone in the loop,” and “collaborating” were all terms providers used to describe the importance of the collaboration and consistency necessary for success when attempting to shift the patient's picture to one of likely or imminent death. This strategy involved providers communicating with each other, collaborating, and agreeing about (or agreeing to go along with) the patient's prognosis, thus presenting a united front to the patient and family regarding the patient's prognosis and possible treatment options both within and across disciplines. One nurse described the importance of working together:

I'm very careful to work in concert with physicians in my setting so that the family isn't hearing from the physician, “Press on, press on,” and from the nurse, “Why are we doing this?” Because that creates incredible distress for families.

This nurse went on to say that when she had concerns regarding the level of aggressiveness of treatment, she first went to the physician to find out what the physician had discussed with the family and then she and the physician often approached the family together to discuss treatment options. Important opportunities for this type of provider-to-provider collaboration occur on a regular basis during rounds, shift-to-shift reports, curbside consults, and/or in written form in patient charts.

For providers working together included sharing (or agreeing to go along with) a similar interpretation of the patient's picture and having similar goals. Providers described how family members, in search of more optimistic answers, often made inquiries of more than one provider regarding the patient's condition or prognosis. According to providers, families often compared information from multiple providers, and thus inconsistent information or a careless comment from one provider could undermine a patient's or family's ability to begin to accept imminent death. As one provider described, “I think the worst thing we could do is give conflicting information to people.” Almost all nurse providers noted that when providers did not work together, the process of shifting patients and families toward more realistic treatment decisions was often undermined. Indeed, if providers were not working together, they limited both the number and the effectiveness of their strategies. Working together required vigilance from providers, usually nurses, making sure that all providers were telling the patient and family the same thing.

Family meetings

Family meetings were described as an effective mechanism for bringing both providers and patients and families together. Meetings were often triggered by a change in the patient's status, usually a deterioration, and were intended to help shift the patient or family to a new picture that was often less optimistic. Among providers' purposes for family meetings were creating a time and space for providers, patients, and families to work together; creating a new, less optimistic picture; and laying out realistic treatment options. One physician noted the importance of family meetings when working with patients in general and when working with patients near the end-of-life in particular:

But I think the key, and the thing that is missed so much by doctors, is having really good communication with the patient, with the family; having family conferences [is] very, very important—trying to reach [a] kind of an understanding between you and the patient about what might need to be done if they get sicker.

Providers who had more experience working with terminally ill patients also described the importance of finding out who the key players in a family were and making sure to incorporate them in family meetings from the beginning in order to keep their big picture updated. Providers found that family members who had not been with the patient as the patient's illness progressed often did not share the same picture and became problematic for providers. Indeed, many providers described the scenario of the faraway relative, usually a son or daughter, arriving late on the scene and demanding aggressive treatment for the patient. Providers explained that searching for and somehow including these people in family meetings (e.g., by conference calls or regular telephone updates) often mitigated problems in later discussions about treatment options, in part because it increased the likelihood they would come to share a picture similar to that of providers.

Creating new expectations

A specific type of teaching by providers involved creating new expectations. Providers described such things as “explaining the progression of the illness,” “that things are going to get worse,” and that this disease “ends in death.” The best-case scenario, explained the providers, was one in which providers were engaged in patient/family teaching throughout the patient's illness (e.g., beginning with laying the groundwork). Providers described working hard to get patients and families to expect deterioration in their condition. According to providers, when patients or families expected deterioration, they could realistically plan for the anticipated change. However, if an unexpected deterioration occurred, patients and families were more likely to request unrealistic treatment. One provider said that it was important that patients have accurate expectations so they could have a “clear understanding that things are going to progress, that death is inevitable. So, it's not the shock and horror of ‘Oh, I’ve got a new symptom!'” As the providers explained, once a patient's or proxy's expectations became more realistic about the patient's condition, he or she was not surprised by the deterioration and did not make requests for unrealistic treatments.

Changing scope of choice

According to providers, changing the scope of choice entailed introducing the patient to new choices believed realistic by a provider. It was especially important because often the default choices are full code and continued aggressive treatments. In changing the scope of choices, providers indicated they might begin by including choices such as advance directives, hospice, do not resuscitate, and comfort care only. One physician indicated she believed she ought to discuss resuscitation with all patients; however, she only tended to have those discussions with patients who she thought were not going to do well during their hospitalization.

Sometimes we do bring it up [DNR] in certain populations when they come into the hospital. If these things were to happen to you, I usually start out by saying, “I don't expect you to die tonight, your heart to stop or something like that, but in the event that that were to happen, what do you want us to do?”

Some providers also described taking options out of the scope of choice (e.g., hemodialysis, chemotherapy, and blood transfusions). One provider, describing talking to a patient's son, noted:

So he came in, and he just sort of felt like we should give her more blood transfusions and stuff. And I needed to explain to him that this wasn't helping her at all. We had tried that route, and now we needed to deal with that she was going to be dying soon.

Changing the scope of choices was useful for shifting the patient's expectations from cure to a good death and providing realistic treatment options from which to choose. This strategy was used often in conjunction with changing the value of treatment options.

Changing the value of treatment options

Providers explained that changing the social value of treatment options entailed raising the value of comfort care so a patient or proxy did not feel he or she was choosing comfort care as a second-best option. As one nurse stated:

What I end up doing a lot is getting away from the word treating. And doing a lot more of, “We can do a lot of things to make her feel better.” And so a lot of times it is rephrasing, and I pull away from using treating, curing, and fixing, anything like that. Because I try to put everything on an equal plane.

At the same time the providers worked to lessen the value of life-support or curative-treatment options. Often providers emphasized the negative effects of treatment. One provider noted how life support could be “an unnatural way of prolonging someone's suffering.” Another provider emphasized the side effects of continued chemotherapy: “I don't think this is going to do much for you, just make you sick.” According to providers, once information about treatment options was revalued, options that were previously unthinkable (e.g., hospice) became possible choices for patients or their proxies. This strategy also commonly involved a change of patient indicators to those more reflective of patient comfort or quality time for patients and families together.

Changing indicators

Providers reported that an aspect of helping patients and families shift their understanding of the big picture was changing the indicators they used to monitor the patient's condition. An indicator is a selected piece of information that is watched and used as a symbol of the larger picture. For example, if a patient has had a recent bone marrow transplant, her family may be monitoring the patient's blood counts as the indicator of how the patient is progressing. Although the patient's counts may be improving, other previously unknown indicators (e.g., oxygen saturation) may signal deterioration in the patient's condition. Indicators and their interpretations were found to shift throughout a patient's illness. At any given time indicators varied in their capacity to reflect accurately the patient's overall picture. In addition, families and patients often tended to focus on the indicators that looked good, that is, reflected the most optimistic picture. Thus it was up to providers to replace the indicators families were using and to supply and interpret new indicators they believed to be more reflective of the patient's overall condition. One nurse described how a family had been using an indicator, blood pressure, that was no longer reflective of the patient's overall condition. She said,

Some people have a really hard time catching on to like how ill their family member is, and they take little tiny bits…of good news and totally blow it out of proportion.

Though the patient's blood pressure had stabilized, the patient's overall condition was still grim, and the provider described how she urged the family to look at urine output and oxygen levels as better indicators of the patient's overall condition.

Although patients and families may begin to understand a new picture, they still may be unwilling to accept or act on it. In that situation, providers reported they then turn to helping patients and families accept the new picture.

Accepting a New Picture

Health care providers reported they used the last group of strategies when their purpose was to facilitate a patient's or family's acceptance or maintenance of the shifted, more accurate picture. If a patient or family had accepted a new picture, it would be evident by their making choices that reflected an understanding similar to that of the health care providers. In addition, acceptance usually ensured that patients and families made decisions that would more likely result in a good death. Strategies used by providers included involving others, redirecting hope, and repeating and reinforcing information.

Involving others

Many providers described the importance of involving others to help families accept a terminal prognosis. This strategy included calling in social workers, outside clergy, hospital chaplains, and palliative care services. A nurse described when she called the social worker:

[I]f you see some of them [family members] having a hard time dealing with it [impending death], they can help focus on a little more of the short-term counselingtype stuff. It's appropriate to bring a social worker in, you know, when you're dealing with all that stuff, death, and they've got heavy issues going on.

Other providers, especially chaplains and social workers, were said to complement the work of nurses and physicians in helping patients and families accept a terminal prognosis.

Redirecting hope

Experienced providers described that “changing what people hope for” rather than taking away hope facilitated patients' and families' acceptance of a new picture and led to a treatment decision, such as pain control, more consistent with a good death. One physician noted, “I look at redirecting hope rather than just destroying it.” This same physician described an experience with another patient as an additional example of how hope may be redirected:

She was very hopeful she would see that 12th grandchild; it is unlikely that will happen. So, does that mean she's lost hope? No, it's being redirected again from that goal to, you know, I'm not going to have pain today.

According to providers, redirecting “what people hope for” –rather than saying, “There is no hope”—C palliative options. Indeed, many of the more experienced providers described high levels of frustration with other providers who made comments like, “There is no hope” or “There's nothing more we can do.” One nurse noted that there was always something providers could offer and that to indicate otherwise was “somewhat of an abandonment.”

Repeating and reiterating information

Most providers described the importance of repeating and reiterating information to patients and their families regarding a terminal prognosis or imminent death in order to help them come to accept and to maintain that acceptance of a terminal prognosis. Providers used such terms as “repeating,” “going over and over,” “readdressing on a regular basis,” “reinforcing,” “reeducating,” and “reiterating” to describe the repeated going over of information with patients and families. One nurse, describing listening to a physician explain information to the family about treatment withdrawal, said, “I feel comfortable saying, ‘Well, this is what the doctor was telling you.s’ Because I know the doctor already explained it to them. I'm just reiterating what they've already said.” Another nurse described the importance of finding out exactly what was said to the patient's family on the previous shift so that she could reinforce it and then pass that information along to the next shift. The ability to reinforce and repeat information given to the patient or family was contingent on providers working together.

In summary, strategies that helped patients and families shift their understanding and come to accept a new prognosis were usually done in concert. Often multiple strategies were used together and repeatedly as a patient and family shifted their understanding of the patient's picture. How quickly or slowly the patient proceeded through an illness trajectory was an important factor that providers took into account when working with patients and families. When providers perceived that the length of time until a patient's death was relatively short (days or weeks), they described intervention implementation as “being up-front,” “zooming in,” “pushing,” or “confronting.” In contrast, when providers thought more time existed (months), they used such phrases as “being gentle,” “nudging,” “hinting,” “bringing it up,” and “letting it drop” to describe how they implemented strategies.

Evaluating Interventions

According to health care providers, evidence that the patient and family shared the providers' picture included consensus among the major participants (providers, family members, and patient) regarding the course of future treatment and goals. Reaching consensus on a shared picture allowed patients, their families, and providers to shift toward a goal of dying well. One provider noted the shift in family members' goals once they accepted that their loved one was going to die, “but it is interesting how families sort of crystallize into making sure they get to enjoy their relative, their loved one. You know, that becomes their focus when they realize that [the patient is going to die].” Consensus, however, was not necessarily a steady state and could be disrupted by any number of things. Providers with more experience, usually nurses, described continually assessing the situation for signs of potential disruption and intervening early to mitigate disruption of consensus.

According to providers, patients who maintained unrealistic goals did not meet those goals, did not use time well, made decisions leading to useless pain and suffering, and were more likely to have a bad death.

And there are the people who right up until the very last moment, the family did not admit that the person was going to die. And so we literally had to code them to the end, which is sad because they never really had a chance to be with that person. We were the ones with that person in the end, which is sad. And it's like you can't do anything about that sometimes; certain families just will not admit how critically ill their family member is and that's that.

Until goals were reconciled or the patient died, providers often continued to use strategies to shift the patient's understanding of the big picture or to facilitate acceptance of a more accurate picture. According to providers, unless goals had been reconciled, it was difficult to assist a patient or family member in preparing for death. When a patient or family member maintained unrealistic goals, such as continuing curative treatment, providers often felt obligated to continue that treatment in accordance with the wishes.

Discussion

Patient decisions and whether they appear realistic change over time and vary by perspective. Consistent with the findings from previous research studies (Kayser-Jones, 1995; Markson et al., 1997; Sullivan et al., 1996; Zussman, 1992), providers in this study intervened when they perceived that patients or their proxies were making unrealistic choices that would lead to poor outcomes. The strategies providers used targeted the patient's overall understanding of their big picture in a belief that changing this picture would result in different choices. This is also consistent with the suggestion from other studies that a more accurate patient understanding of prognosis may increase the likelihood patients would choose less aggressive treatments (Simmonds, 1996; Weeks et al., 1998).

In one way, provider strategies to shift treatment decisions can be interpreted as providers helping the patient make truly informed autonomous decisions, ones based on what providers consider a more accurate understanding of the situation. At the same time, providers' attempts to shift patient and family understanding can be interpreted as paternalistic or even coercive. However, to reduce these findings to a debate about paternalism and autonomy obscures the more complex realities of providers' roles in decision making near the end of life.

Decisions made near the end of life often have profound consequences. Deciding whether, when, or how one ought to intervene when one believes a patient to be making unrealistic decisions is difficult. Providers often have access to knowledge and experiences that patients and families do not. Deciding how best to share this knowledge and experience with patients and families requires that providers carefully examine their own motives and beliefs about death and dying. Providers who do this largely invisible work described an ongoing integrated process of bringing patients and families along over time to a point where the patients or proxies make informed and realistic choices. To be successful, this process requires adequate time to interact with the patient and the family and attention to multidisciplinary collaborative efforts.

Providers' perspectives are presented here. The intent was not to imply that only one picture exists, that all providers share one picture, or even that there is such a thing as an accurate picture. Rather, the intent was to illustrate providers' behaviors when they conclude that the patient or proxy does not have an accurate big picture. This study did not explore how end-of-life goals and decisions are negotiated with providers, patients, or families who define a good death as never giving up, nor did it investigate providers who don't see their role as helping patients achieve a good death. Further study is needed to explore how patients and family members come to an understanding of the patient's condition and prognosis and draw on that understanding in their decision making.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Bowers' Research Group at UW-Madison and Dr. Virginia Tilden at Oregon Health Sciences University.

Footnotes

Predoctoral fellowship: National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR); predoctoral fellowship number: F31 NR07265-01.

Dissertation research award: Beta Eta chapter of Sigma Theta Tau.

Postdoctoral fellowship: NINR; postdoctoral fellowship number: T32 NR07061-09.

References

- Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Goldman L, Harrell RE. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner LF, Beaton KI. Life–death decisions in health care. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guba E, Lincoln Y. Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones J. Decision making in the treatment of acute illness in nursing homes: Framing the decision problem, treatment plan, and outcome. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1995;9:236–256. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.2.02a00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markson L, Clark J, Glantz L, Lamberton V, Kern D, Stollerman G. The doctor's role in discussing advance preferences for end-of-life care: Perceptions of physicians practicing in the VA. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton SA. Reconciling decisions near the end of life: A grounded theory study Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Norton SA, Talerico KA. Facilitating end-of-life decision-making: Strategies for communicating and assessing. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2000;26:6–13. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000901-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR NUD*IST 4 [Computer software] Qualitative solutions and resources Ltd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. Nonnumerical unstructured data indexing searching and theory-building software. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L. Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In: Maines DR, editor. Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1991. pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds AL. Decision-making by default: Experiences of physicians and nurses with dying patients in intensive care. Humane Health Care International. 1996;12:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon MZ, O'Donnell L, Jennings B, Guilfoy V, Wolf SM, Nolan K, Jackson R, Koch-Weser D, Donnelley S. Decisions near the end of life: Professional views on life-sustaining treatments. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:14–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Qualitative analysis for the social scientist. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KE, Hebert PC, Logan J, O'Connor AM, McNeely PD. What do physicians tell patients with end-stage COPD about intubation and mechanical ventilation? Chest. 1996;109:258–264. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.1.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Licks S, Lynn J, Wenger N, Connors AF, Jr, Phillips RS, O'Connor MA, Murphy DP, Fulkerson WJ, Desbiens N, Knaus WA. Do advance directives provide instructions that direct care? Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:508–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno J, Lynn J, Wenger N, Phillips RS, Murphy DP, Connors AF, Jr, Desbiens N, Fulkerson W, Bellamy P, Knaus WA. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the Patient Self-Determination Act and the SUPPORT intervention. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Garland MJ, Nelson CA. Decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, Thompson M, Eggman SC. Family decision making in foregoing life-sustaining treatments. Journal of Family Nursing. 1999;5:426–442. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, Peterson LM, Wenger N, Reding D, Harrell FE, Kussin P, Dawson NV, Connors AF, Jr, Lynn J, Phillips RS. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SA, Daley BJ. Family perspectives on dying in long-term care settings. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1999;25(11):19–25. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19991101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zussman R. Intensive care: Medical ethics and the medical profession. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]