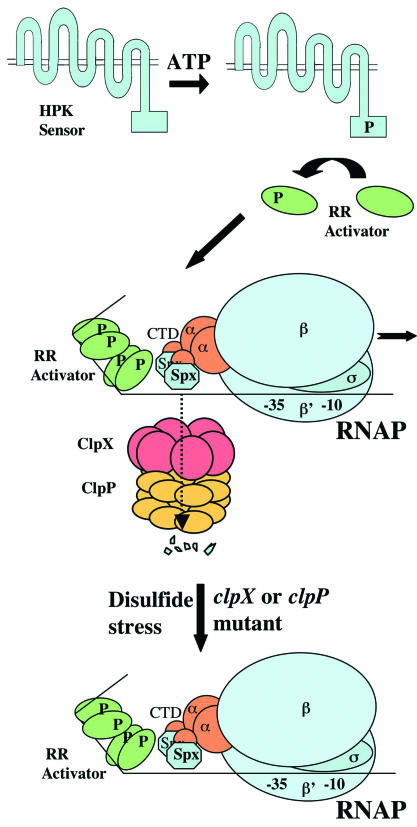

Spx is a unique RNA polymerase (RNAP)-binding protein that is highly conserved among low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria and certain members of the Mollicutes. In the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus subtilis, its primary target is the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the RNAP α subunit (αCTD) (43). The interaction of Spx with αCTD interferes with transcriptional activation that is mediated by certain response regulators of the two-component signal transduction systems required for mobilizing developmental and metabolic programs (Fig. 1). The unique mechanism of Spx-dependent repression prompted the term “anti-alpha” to describe proteins with its mode of action. More recent work by members of my group has revealed that Spx can also activate transcription in response to oxidative stress (42). These findings provide evidence that Spx plays a role in the physiological framework of B. subtilis and perhaps other gram-positive bacteria. The data obtained thus far indicate that Spx is a global transcriptional regulator that exerts both positive and negative control over transcription initiation. In doing so, it can significantly change the complexion of the transcriptome so as to activate the genes required for alleviating the consequences of exposure to toxic oxidants and to repress genes whose products either are unnecessary or might exacerbate the damage caused by oxidative stress.

FIG. 1.

Positive transcriptional regulation of a two-component signal transduction system and negative control exerted by the Spx protein. The histidine protein kinase (membrane-bound HPK sensor) autophosphorylates in response to a stimulus (i.e., ComX) and donates the phosphate to the response regulator (RR activator), which then interacts with a promoter region of a gene under its control. Spx is degraded by the protease ClpXP, allowing transcriptional activation to proceed. The subunits of RNAP, β, β′, α, and σ, are indicated, as is the location of the αCTD. Upon disulfide stress or in either a clpX or clpP mutant, Spx accumulates and binds to the αCTD and blocks the activator-RNAP interaction.

SUPPRESSORS OF PLEIOTROPIC clpX AND clpP MUTATIONS

The spx gene was found in B. subtilis to be the site of mutations that suppress clpP and clpX mutations. The clpP and clpX genes encode the proteolytic and substrate-binding components of the ClpXP protease, respectively (20, 65). ClpX is an ATPase and unfoldase that catalyzes the denaturation of substrate protein and, when it is bound to ClpP, the translocation of substrate polypeptide into the proteolytic chamber formed by the ClpP heptamer. It is one of three Clp protease subunits of B. subtilis; the other subunits are ClpC and ClpE (10, 28). Mutations in the clpP and clpX genes were observed to block genetic competence development and sporulation (18, 30, 35) and to cause severe growth impairment, especially on minimal synthetic media (35). Mutations in clpX reduced the activity of the σH form of RNAP (30, 31), which is required for the transcription of genes induced early in sporulation (12) and for activation of the srf operon, which marks the first stage of competence development (8, 36, 60). Mutation of the clp genes also blocks anaerobic growth, in part, by preventing the activation of genes within the resDE regulon (41, 57). ResD and ResE constitute a two-component signal transduction system required for induction of the fnr (anaerobic transcriptional regulator) gene, the hmp (flavohemoglobin) gene, the nar (nitrate reductase) operon, and other genes required for aerobic and anaerobic respiration.

Studies of clpX and clpP in B. subtilis in my laboratory have focused on regulation of the srf operon, which encodes the subunits of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase that catalyzes the synthesis of the lipopeptide surfactin (3, 36). This operon also contains the essential competence regulatory gene, comS (11, 24), the product of which is a 46-amino-acid peptide that functions in activation of the transcription factor, ComK (59, 61). ComK activation marks the second stage of competence development and leads to expression of genes that function in DNA uptake. Transcription of the srf operon is under quorum-sensing control involving the modified peptide pheromone ComX (32) and the two-component regulatory system ComPA (51, 63). Like its homologs ResDE, ComP, the sensor histidine kinase (Fig. 1), and ComA, the response regulator (Fig. 1), activate transcription in response to some stimulus, which in this case is the presence of the ComX pheromone. By direct interaction with ComP, the pheromone induces ComP autophosphorylation. The phosphate bound to a histidine residue in ComP is then acquired by ComA, which, thus activated, binds upstream of the promoter region of the srf operon as a tetrameric complex (38, 40, 51). Thus assembled, ComA interacts with RNAP, thereby stimulating transcription initiation (Fig. 1). ComA-phosphate-dependent transcription of srf is severely impaired in clpP and clpX mutants (35).

Suppressor mutations of clpX arise frequently, and they have been shown to elevate srf-lacZ expression in a clpX mutant background. The suppressor mutations, designated cxs (clpX suppressor), mapped to two loci. Mutations were first detected in the rpoA gene encoding the RNAP α subunit (39). Two codon substitutions (Y263C and V261A) in the region of rpoA that in Escherichia coli encodes α-helix 1 of αCTD conferred the Cxs phenotype. Helix 1 is important in activator-stimulated transcription and in RNAP binding to extended promoter sequences, such as the rRNA operon UP element (16, 52). Defects in competence and growth in minimal medium conferred by the clpX null mutation were at least partially alleviated by the rpoAcxs mutations (39). The heat sensitivity of the clpX mutant was retained, however.

The majority of the clpX suppressor mutations mapped to the yjbD gene, which encodes a highly conserved 15-kDa product (2, 35). All mutations were recessive, and a neomycin resistance cassette inserted into the gene conferred a Cxs phenotype. The loss-of-function mutations in yjbD, like the rpoAcxs mutations, only partially suppressed clpX, as the heat sensitivity of the clpX mutant was retained in the clpX yjbD double mutants. Mutations in the yjbD gene also suppressed clpP with respect to competence development and growth on minimal medium, but cells retained the Spo− phenotype due to the function of ClpP in forespore gene expression (48). The yjbD gene was renamed spx suppressor of clpP and clpX.

PROTEOLYTIC CONTROL OF SPX

The severe phenotype of clpX can be attributed to the increase in the concentration of the Spx protein (35, 44). Western blot analysis of clpX and clpP mutant extracts revealed high levels of Spx, suggesting that Spx is a substrate for ClpXP-catalyzed proteolysis (Fig. 1). Initial attempts to demonstrate proteolysis of Spx in vitro were unsuccessful due to the nature of the purified Spx protein, which was obtained by using an expression system that appended two amino acids to the C terminus (44). However, a form of Spx containing an unaltered C terminus was efficiently degraded by ClpXP in vitro (43). Proteolysis reaction mixtures containing ClpCP with the adaptor protein MecA (see below) also showed Spx degradation, but for unknown reasons only clpX and clpP mutations resulted in Spx accumulation in vivo, while a clpC mutation did not affect the Spx concentration (43).

The Spx protein negatively affected both stages of competence development, the activation of srf operon transcription and the activation of ComK. In noncompetent cells, ComK is bound to an inhibitory complex composed of the protease ClpCP and MecA, a substrate-binding factor for ClpCP (58, 59). At a high cell density, the srf operon and the comS gene contained within this operon are transcribed, and the ComS protein is produced. ComS, through its interaction with MecA, causes the release of ComK, which then activates its own gene's transcription, as well as that of the late competence operons (61, 62), whose products function in DNA uptake. Spx interacts with MecA and in doing so interferes with ComS-dependent ComK release from MecA/ClpCP (37). However, this effect does not explain how Spx negatively influences srf operon transcription.

ANTI-ALPHA ACTIVITY OF SPX

One mutant allele of spx that resulted in the Cxs phenotype, spxcxs-16, was a missense mutation that conferred an amino acid substitution at the conserved Gly 52 residue of the Spx protein (35). The mutant G52R product was found to be stable in the clpX mutant background but was inactive, as shown by the allele's recessive nature. The data suggested that the target of Spx, contact with which resulted in growth and developmental defects in B. subtilis clpX mutants, had a reduced affinity for the Spxcxs-16 protein.

To identify the Spx target, a yeast two-hybrid screening analysis (6) was performed by using the wild-type spx coding sequence fused to the DNA encoding the DNA-binding domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gal4 and a B. subtilis genomic library in a vector bearing the activation domain of Gal4 (43). Clones sponsoring productive interaction were further screened by introducing them into a strain bearing a DNA-binding domain fusion containing the spxcxs-16 coding sequence. Two clones that did not exhibit interactions with the mutant spx-GAL4DB product were isolated. Both of these clones carried the region of the rpoA gene encoding the CTD, which contained the sites of both rpoAcxs mutations. A GAL4AD fusion was constructed by using the CTD of the rpoAcxs-1 mutant. When this fusion was combined with the spx-GAL4DB domain fusion, no interaction was detected. The interaction between Spx and the α subunit of RNAP was confirmed by a pull-down reaction in which a six-His-tagged version of Spx and Ni-chelate chromatography were used and by isothermal titration calorimetry (4; S. Nakano, R. G. Brennan, and P. Zuber, unpublished data).

The activity of Spx was reproduced in vitro by using runoff transcription reactions with purified RNAP and DNA promoter templates from the srf operon and the ResDE-controlled gene hmp (43). Spx, but not the Spxcxs-16 mutant, repressed ComA-dependent transcription initiation from srf promoter DNA and transcription from the hmp promoter in reaction mixtures containing ResE and ResD. Spx did not affect transcription from the consensus σA promoter of the rpsD gene, which encodes ribosomal protein S4 (23). Transcription of rpsD does not require an activator and was not affected by a mutation in clpX (30). RNAP purified from rpoAcxs-1 mutant cells, when combined with either ResD- or ComA-phosphate in a transcription reaction mixture, catalyzed transcription that was insensitive to the presence of Spx protein.

SPX-DEPENDENT TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION DURING OXIDATIVE STRESS

The repression caused by the Spx interaction with αCTD explained the phenotype of clpX, spx, and rpoAcxs mutants and prompted me and coworkers to label Spx an anti-alpha protein since its primary target is αCTD and not promoter DNA. However, up to this point, Spx activity in vivo had been observed only in a clpX or clpP mutant background, and its role in the physiological framework of the B. subtilis cell was still unknown. Information concerning the role of Spx in the cell was obtained by performing a microarray hybridization analysis to identify the genes whose expression is negatively or positively affected by an Spx-RNAP interaction in a Clp+ genetic background (42). The Spx protein is present at only very low levels in wild-type cells (35, 44), and attempts to overexpress Spx in B. subtilis were unsuccessful due to the rapid degradation of the protein by ClpXP. To elevate the Spx concentration in a controlled manner, an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible mutant allele of spx was constructed that coded for a protease-resistant form of the protein. The C terminus of Spx resembles the SsrA peptide tag of B. subtilis (64), which is normally appended to the truncated products of interrupted translation to target the nascent polypeptide for proteolysis by ClpXP (21). The last two codons (specifying AN) were replaced by two Asp codons (Fig. 2) to create the mutant allele spxDD. When a high concentration of the mutant product was produced, a ClpX-like phenotype was observed, which included repression of the srf operon (42). This repression did not occur if the mutant construct was expressed in an rpoAcxs-1 mutant.

FIG. 2.

(A) Amino acid sequence of Spx and the sites of the CXXC motif, the conserved G residue that is the site of the Spxcxs-16 substitution, and the DD substitution at the extreme C terminus that renders Spx insensitive to ClpXP proteolysis. The boldface type indicates the regions of sequence identity shared by the Spx orthologs. The secondary structure predictions (50) for Spx and the E. coli R773 ArsC protein were determined, and the structures were aligned (H, α helix; S, β strand; C, coil). The four conserved β strands that form the mixed β sheet are indicated. (B) Structural representation of the ArsC protein with the C-terminal region (where homology with Spx departs) omitted. The positions of the conserved Cys10 residue, the Gly52 residue, and the four-strand mixed β sheet (yellow) are indicated.

In the microarray hybridization experiment, genes that were induced or repressed in the IPTG-treated spxDD cells but not in the IPTG-treated spxDD rpoAcxs-1 cells were identified. This screening procedure allowed us to determine which genes were affected by Spx-RNAP interaction. As predicted, all the genes of the srf operon were repressed when spxDD was expressed in the RpoA+ background, as were other genes of the ComA regulon. Several operons whose products function in the biosynthesis of purines, pyrimidines, amino acids, and vitamins were also repressed. The latter finding is in keeping with the observed ClpX phenotype, which includes poor growth on minimal medium.

Over 100 genes were induced by the Spx-RNAP interaction, and two of the most strongly expressed genes were trxA and trxB, encoding thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase, respectively. Other genes that function in thiol homeostasis, including three genes encoding thioredoxin-like products, were found in the induced group, which suggested that Spx functioned in controlling the cell's response to oxidative agents. This suggestion was supported by the finding that an spx null mutant and a strain bearing the rpoAcxs-1 mutation did not grow on medium containing the thiol-specific oxidant diamide (42). The level of trxA and trxB transcripts in wild-type cells increased after diamide treatment, but not in the spx and rpoAcxs-1 mutants. Diamide-induced disulfide stress also increased Spx-dependent repression, as indicated by a reduction in the srf operon transcript concentration that was not observed in the spx null and rpoAcxs-1 mutants. The microarray data and measurement of specific transcript levels indicated that Spx-dependent transcriptional activation and repression increase in cells undergoing disulfide stress. An Spx-RNAP interaction appears to be essential for the cell to alter the pattern of gene expression in order to cope with the damaging effects of toxic oxidants.

Diamide treatment also resulted in an increase in the concentration of the Spx protein, which was due in part to a posttranscriptional event, since the increase in Spx concentration was observed in cells bearing a DNA construct composed of the wild-type spx coding sequence located downstream from an IPTG-inducible promoter. Among the explanations for the increase in Spx levels is the idea that ClpXP activity is inhibited or diverted when cells encounter a toxic oxidant. Another possibility is that the susceptibility of Spx to ClpXP-catalyzed proteolysis is altered by an oxidation-induced conformational change. The presence of a CXXC motif near the N terminus of Spx (Fig. 2) suggests that there is a mechanism by which the Spx protein is directly altered by oxidation, yielding a form of Spx that is a poor substrate for ClpXP. Alternatively, ClpXP activity could be altered by oxidation. The ClpX protein contains a Zn-finger domain in the N-terminal region, in which a Zn atom is coordinated by five Cys thiolates (5). Oxidation of one or more of the Cys residues could result in release of Zn and a reduction in ClpX activity. Changes in chaperone activity by oxidative release of bound Zn have been reported in the case of Hsp33 (22, 25).

While it is a simple matter to envision transcriptional repression as carried out by Spx, it is not clear how transcription initiation can be activated, as there is no evidence yet indicating that Spx can bind DNA either in a sequence-specific manner or in a nonspecific manner. Spx could bind αCTD of RNAP and direct the holoenzyme to specific promoter sequences associated with oxidative stress-induced genes. The protein itself could undergo a conformational change after an oxidation event mediated by the CXXC disulfide pair, which unmasks a DNA-binding domain. The mode of action would be akin to that of MotA of phage T4, which binds region 4 of E. coli σ70 and essentially drags RNAP to the T4 phage promoters while preventing the normal interaction with host genes (49). Alternatively, Spx could function as an extension of the αCTD that introduces new activator binding surfaces to the RNAP holoenzyme. In this way, Spx could serve as a mediator through which activators can gain contact with RNAP to stimulate transcription at activator-controlled promoters. The two mechanisms of Spx-dependent activation are not mutually exclusive, and each applies to specific promoters.

Control of the genes activated in response to oxidative stress is exerted at the level of transcription initiation by a number of regulatory proteins (55, 68) that contain Cys residues that are crucial for function and control. In enteric bacteria (and probably in Streptomyces) OxyR activates transcription by recruiting RNAP to promoter DNA in response to peroxide for thiol-specific oxidation (56, 67). This molecule has two redox-active cysteines that form an intramolecular disulfide linkage or can undergo various degrees of oxidation, which promotes a change to the active conformation (27, 67). The genes encoding catalase, alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, glutaredoxin, and glutathione reductase are all activated by OxyR (68). In B. subtilis, PerR (7) is a Zn-binding protein that exerts negative control but is released when peroxide stress is encountered. Peroxide oxidation of Cys ligands results in release of Zn and inactivation of the repressor. Likewise, OhrR is a negative transcriptional regulator of genes that function in organic peroxide resistance (15, 34). Release of repression involves the oxidation of a conserved cysteinyl residue in OhrR to a sulfenic adduct.

In eukaryotes, regulatory factors associated with cellular stress undergo changes in conformation and activity mediated by the redox state of Cys residues. The mammalian heat shock factor (HSFI) possesses two conserved cysteines that constitute a redox center, which is sensitive to oxidation (1). Both heat shock and H2O2 treatment activate HSFI, which then stimulates heat shock protein gene transcription. The yeast AP-1-like protein (Yap1) activates transcription of thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, and thioredoxin peroxidase in response to oxidative stress (9, 17). It also contains redox-active cysteines, oxidation of which changes the nuclear localization of Yap1 (29, 66).

The data that have been obtained thus far indicate that Spx is a unique RNAP holoenzyme subunit. Changes in RNAP holoenzyme composition accompany the oxidative stress response in other organisms, but in these cases the response involves association of an alternative sigma subunit. Streptomyces species possess a regulatory system that operates through a minor holoenzyme form that activates genes that function in thiol-specific oxidant resistance (26, 45-47). This system contains the RNAP sigma subunit σR, which is controlled by the redox-sensitive anti-sigma factor RsrA. The sigma factor σR directs transcription of the gene encoding thioredoxin when the cysteinyl residues in RsrA undergo oxidation. Like PerR, RsrA possesses a Zn-binding domain containing three conserved Cys residues. Oxidation results in release of Zn and a loss of σR affinity. The similarities between Spx and the ArsC (arsenate reductase) family of proteins (see below) suggests that a metal ion is not involved as a cofactor in the activity or control of Spx.

SPX, AN ARSC FAMILY MEMBER WITH ORTHOLOGS IN GRAM-POSITIVE BACTERIA

The trmA gene encoding an Spx homolog was previously discovered in Lactococcus lactis as the site of mutations that confer heat resistance to recA mutants (13). RecA is known to be the multifunctional protein that regulates the SOS response to DNA damage and that mediates recombination. A requirement for this protein for heat resistance has been observed only in L. lactis. Mutations in trmA were independently found to suppress mutations in the clpP gene (14). clpP mutants were suppressed by trmA mutations with respect to heat sensitivity, which was attributed to increased proteolytic activity of a clpP mutant when trmA was inactive. One target of both RecA and the Clp protease is L. lactis HdiR, which negatively controls the SOS response and bears some resemblance to UmuD, a known substrate for RecA and the Clp protease, but contains a DNA-binding domain that mediates interaction with the promoter of a DNA damage-inducible gene (53). RecA and the Clp protease ClpXP function in the degradation of HdiR in response to both heat stress and DNA damage. It is not known to what extent the activity of HdiR is related to heat sensitivity in recA or clpP mutants of L. lactis or if mutations in trmA result in loss of HdiR activity in the recA and clpP mutant backgrounds.

A CD-BLAST search of Spx revealed that this protein is a member of the ArsC (arsenate reductase) family of proteins and exhibits significant secondary-structure homology with the ArsC protein of E. coli plasmid R773 (33) (Fig. 2). Conserved in members of the ArsC family is the four-strand mixed β sheet (strands labeled 1 to 4 in Fig. 2), each strand of which is found in the appropriate position in Spx. The active Cys10 residue of ArsC is located in the loop between the first β strand 1 and the first helix, which is also conserved in the Spx protein and its homologs. The helix at the extreme C terminus of Spx that contains the sequence required for recognition by ClpXP is not present in ArsC. The His8 residue of ArsC, which is thought to lower the pKa of Cys10 (19), is absent in Spx, but the Arg60, Arg94, and Arg107 residues that form an anion-binding pocket that is thought to stabilize the Cys-bound arsenate in ArsC (54) appear to be conserved in Spx. The Cys at position 13 of Spx is replaced with a Ser in ArsC. It is possible that the three-Arg pocket, instead of stabilizing an anion such as arsenate, stabilizes a thiolate anion of Cys13 to facilitate oxidative disulfide bond formation.

Orthologs of Spx can be found in most low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus, Listeria, Enterococcus, Lactococcus, and Streptococcus. Most of these molecules contain the CXXC motif at the N-terminal end, and three blocks of strong sequence identity were detected in an alignment of homologs (Fig. 2). One block contains the G residue which is highly conserved and is the site of the Spxcxs-16 substitution (43). The C-terminal ClpX recognition sequence appears not to be conserved in all of the Spx orthologs, hinting that some of the orthologs are controlled by regulatory processes different than those controlling the Spx concentration in B. subtilis. The genomic organization in the vicinity of spx is also conserved in many of the low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria in which the spx gene is tightly linked to the mecA gene (Fig. 3) encoding the negative regulator of genetic competence in B. subtilis mentioned above (58). The recent studies showing that Spx affects the activity of MecA/ClpCP (37) suggest that there is a relationship between MecA and Spx. Several of the gram-positive species listed in Fig. 3 are not known to be naturally competent or to possess comK. Hence, MecA is likely to function in processes that require ClpCP protease in addition to regulation of ComK. Might Spx have an additional function as a factor controlling the utilization of MecA by ClpCP in gram-positive bacteria, which could account for tight linkage of the spx gene with mecA? Notably, no such linkage is found in the streptococci (Streptococcus pneumoniae or Streptococcus pyogenes).

FIG. 3.

Conservation in the low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria of the spx locus, showing the tight linkage with the mecA gene (not observed in streptococci). The arrows represent genes and their orientations; the conserved genes of the locus are indicated by shaded arrows.

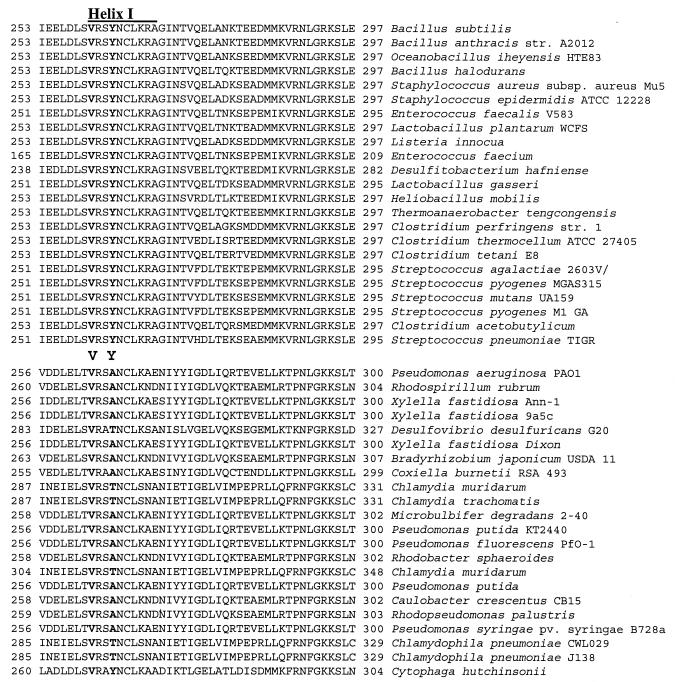

There is a significant correlation between the presence of the spx gene in gram-positive bacteria and the presence of the conserved Tyr residue in the helix 1 region of the RNAP αCTD (Fig. 4). The loss of diamide resistance in mutants bearing the Y263C substitution (42) indicates the importance of this residue in the function of the α subunit. Alignment of the amino acid sequences in this region in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria indicated that there is considerable nonhomology at this position and in the adjacent sequence. The interaction site of Spx may be one of the roles played by this region of the RNAP α subunit.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the RNAP αCTD of gram-positive (top) and gram-negative (bottom) species that include helix 1 and the adjacent sequence in the αCTD. The V and Y residue positions are the sites of the rpoAcxs amino acid substitutions.

Conclusion.

Studies over the years have uncovered systems of gene regulation that are dedicated to controlling the processes of stress response and recovery in bacteria. A more recent line of investigation has focused on the genome-wide effects of the microbial stress response, and it has been demonstrated that a multitude of cellular processes might be affected by a chemical or physical toxic substance and by the regulators that control the response to such agents. The Spx protein may be representative of a new family of RNAP-binding factors that cause genome-wide changes in expression as part of the cell's response to toxic oxidants. The primary target of this protein is the α subunit of RNAP, interaction with which can either repress or stimulate transcription. Since it has no obvious DNA-binding activity, Spx might exert positive control by a unique mechanism. Further study of Spx may reveal a new form of transcriptional control and, perhaps, some unexpected details concerning RNAP holoenzyme structure and activity.

Acknowledgments

I thank M. M. Nakano and S. Nakano for many helpful discussions and for reading the manuscript and R. G. Brennan and members of his laboratory for assistance with studies of Spx and helpful advice.

Research performed in my laboratory is supported by grant GM45898 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, S. G., and D. J. Thiele. 2003. Redox regulation of mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for Hsp gene activation and protection from stress. Genes Dev. 17:516-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann, H., C. Scharf, and M. Hecker. 2000. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins of Bacillus subtilis: proteomics and transcriptional analysis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4478-4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arima, K., A. Kakinuma, and G. Tamura. 1968. Surfactin, a crystalline peptide lipid surfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis: isolation, characterization, and its inhibition of fibrin clot formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 31:488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bains, G., and E. Freire. 1991. Calorimetric determination of cooperative interactions in high affinity binding processes. Anal. Biochem. 192:203-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banecki, B., A. Wawrzynow, J. Puzewicz, C. Georgopoulos, and M. Zylicz. 2001. Structure-function analysis of the zinc-binding region of the ClpX molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18843-18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel, P. L., C.-T. Chien, R. Sternglanz, and S. Fields. 1993. Using the two-hybrid system to detect protein-protein interactions, p. 153-179. In D. A. Hartley (ed.), Cellular interactions in development: a practical approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 7.Bsat, N., A. Herbig, L. Casillas-Martinez, P. Setlow, and J. D. Helmann. 1998. Bacillus subtilis contains multiple Fur homologues: identification of the iron uptake (Fur) and peroxide regulon (PerR) repressors. Mol. Microbiol. 29:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosmina, P., F. Rodriguez, F. de Ferra, G. Grandi, M. Perego, G. Venema, and D. van Sinderen. 1993. Sequence and analysis of the genetic locus responsible for surfactin synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:821-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaunay, A., A. D. Isnard, and M. B. Toledano. 2000. H2O2 sensing through oxidation of the Yap1 transcription factor. EMBO J. 19:5157-5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derre, I., G. Rapoport, K. Devine, M. Rose, and T. Msadek. 1999. ClpE, a novel type of HSP100 ATPase, is part of the CtsR heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:581-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Souza, C., M. M. Nakano, and P. Zuber. 1994. Identification of comS, a gene of the srfA operon that regulates the establishment of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91:9397-9401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubnau, E., J. Weir, G. Nair, H. L. Carter, C. P. Moran, Jr., and I. Smith. 1988. Bacillus sporulation gene spo0H codes for σ30 (σH). J. Bacteriol. 170:1054-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duwat, P., S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1999. Effects of metabolic flux on stress response pathways in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 31:845-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frees, D., P. Varmanen, and H. Ingmer. 2001. Inactivation of a gene that is highly conserved in Gram-positive bacteria stimulates degradation of non-native proteins and concomitantly increases stress tolerance in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 41:93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuangthong, M., S. Atichartpongkul, S. Mongkolsuk, and J. D. Helmann. 2001. OhrR is a repressor of ohrA, a key organic hydroperoxide resistance determinant in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:4134-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal, T., W. Ross, E. E. Blatter, H. Tang, X. Jia, V. V. Krishnan, N. Assa-Munt, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1996. DNA-binding determinants of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase: novel DNA-binding domain architecture. Genes Dev. 10:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasch, A. P., P. T. Spellman, C. M. Kao, O. Carmel-Harel, M. B. Eisen, G. Storz, D. Botstein, and P. O. Brown. 2000. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:4241-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerth, U., E. Kruger, I. Derre, T. Msadek, and M. Hecker. 1998. Stress induction of the Bacillus subtilis clpP gene encoding a homologue of the proteolytic component of the Clp protease and the involvement of ClpP and ClpX in stress tolerance. Mol. Microbiol. 28:787-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gladysheva, T., J. Liu, and B. P. Rosen. 1996. His-8 lowers the pKa of the essential Cys-12 residue of the ArsC arsenate reductase of plasmid R773. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33256-33260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottesman, S., W. P. Clark, V. de Crecy-Lagard, and M. R. Maurizi. 1993. ClpX, an alternative subunit for the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. Sequence and in vivo activities. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22618-22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottesman, S., E. Roche, Y. Zhou, and R. T. Sauer. 1998. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 12:1338-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graf, P. C., and U. Jakob. 2002. Redox-regulated molecular chaperones. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1624-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy, F. J., and T. M. Henkin. 1990. Cloning and analysis of the Bacillus subtilis rpsD gene, encoding ribosomal protein S4. J. Bacteriol. 172:6372-6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamoen, L. W., H. Eshuis, J. Jongbloed, G. Venema, and D. van Sinderen. 1995. A small gene, designated comS, located within the coding region of the fourth amino acid-activation domain of srfA, is required for competence development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 15:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakob, U., M. Eser, and J. C. Bardwell. 2000. Redox switch of Hsp33 has a novel zinc-binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38302-38310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang, J. G., M. S. Paget, Y. J. Seok, M. Y. Hahn, J. B. Bae, J. S. Hahn, C. Kleanthous, M. J. Buttner, and J. H. Roe. 1999. RsrA, an anti-sigma factor regulated by redox change. EMBO J. 18:4292-4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, S. O., K. Merchant, R. Nudelman, W. F. Beyer, Jr., T. Keng, J. DeAngelo, A. Hausladen, and J. S. Stamler. 2002. OxyR: a molecular code for redox-related signaling. Cell 109:383-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruger, E., U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 1994. Stress induction of clpC in Bacillus subtilis and its involvement in stress tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 176:3360-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuge, S., N. Jones, and A. Nomoto. 1997. Regulation of yAP-1 nuclear localization in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J. 16:1710-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, J., W. M. Cosby, and P. Zuber. 1999. Role of Lon and ClpX in the post-translational regulation of a sigma subunit of RNA polymerase required for cellular differentiation of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:415-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, J., and P. Zuber. 2000. The ClpX protein of Bacillus subtilis indirectly influences RNA polymerase holoenzyme composition and directly stimulates sigma H-dependent transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:885-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnuson, R., J. Solomon, and A. D. Grossman. 1994. Biochemical and genetic characterization of a competence pheromone from Bacillus subtilis. Cell 77:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin, P., S. DeMel, J. Shi, T. Gladysheva, D. L. Gatti, B. P. Rosen, and B. F. Edwards. 2001. Insights into the structure, solvation, and mechanism of ArsC arsenate reductase, a novel arsenic detoxification enzyme. Structure (Cambridge) 9:1071-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mongkolsuk, S., and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Regulation of inducible peroxide stress responses. Mol. Microbiol. 45:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano, M. M., F. Hajarizadeh, Y. Zhu, and P. Zuber. 2001. Loss-of-function mutations in yjbD result in ClpX- and ClpP-independent competence development of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:383-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakano, M. M., R. Magnuson, A. Myers, J. Curry, A. D. Grossman, and P. Zuber. 1991. srfA is an operon required for surfactin production, competence development, and efficient sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:1770-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakano, M. M., S. Nakano, and P. Zuber. 2002. Spx (YjbD), a negative effector of competence in Bacillus subtilis, enhances ClpC-MecA-ComK interaction. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1341-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakano, M. M., L. Xia, and P. Zuber. 1991. Transcription initiation region of the srfA operon which is controlled by the comP-comA signal transduction system in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:5487-5493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakano, M. M., Y. Zhu, J. Liu, D. Y. Reyes, H. Yoshikawa, and P. Zuber. 2000. Mutations conferring amino acid residue substitutions in the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase α can suppress clpX and clpP with respect to developmentally regulated transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 37:869-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 1993. Mutational analysis of the regulatory region of the srfA operon in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:3188-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakano, M. M., P. Zuber, P. Glaser, A. Danchin, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3796-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakano, S., E. Küster-Schöck, A. D. Grossman, and P. Zuber. 2003. Spx-dependent global transcriptional control is induced by thiol-specific oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100:13603-13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakano, S., M. M. Nakano, Y. Zhang, M. Leelakriangsak, and P. Zuber. 2003. A regulatory protein that interferes with activator-stimulated transcription in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100:4233-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakano, S., G. Zheng, M. M. Nakano, and P. Zuber. 2002. Multiple pathways of Spx (YjbD) proteolysis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:3664-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paget, M. S. B., J.-B. Bae, M.-Y. Hahn, W. Li, C. Kleanthous, J.-H. Roe, and M. J. Buttner. 2001. Mutational analysis of RsrA, a zinc-binding anti-sigma factor with a thiol-disulphide redox switch. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1036-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paget, M. S. B., J.-G. Kang, J.-H. Roe, and M. J. Buttner. 1998. σR, an RNA polymerase sigma factor that modulates expression of the thioredoxin system in response to oxidative stress in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). EMBO J. 19:5776-5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paget, M. S. B., V. Molle, G. Cohen, Y. Aharonowitz, and M. J. Buttner. 2001. Defining the disulphide stress response in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): identification of the σR regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1007-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan, Q., D. A. Garsin, and R. Losick. 2001. Self-reinforcing activation of a cell-specific transcription factor by proteolysis of an anti-σ factor in B. subtilis. Mol. Cell 8:873-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pande, S., A. Makela, S. L. Dove, B. E. Nickels, A. Hochschild, and D. M. Hinton. 2002. The bacteriophage T4 transcription activator MotA interacts with the far-C-terminal region of the σ70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 184:3957-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollastri, G., D. Przybylski, B. Rost, and P. Baldi. 2002. Improving the prediction of protein secondary structure in three and eight classes using recurrent neural networks and profiles. Proteins 47:228-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roggiani, M., and D. Dubnau. 1993. ComA, a phosphorylated response regulator protein of Bacillus subtilis, binds to the promoter region of srfA. J. Bacteriol. 175:3182-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savery, N. J., G. S. Lloyd, S. J. Busby, M. S. Thomas, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 2002. Determinants of the C-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit important for transcription at class I cyclic AMP receptor protein-dependent promoters. J. Bacteriol. 184:2273-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Savijoki, K., H. Ingmer, D. Frees, F. K. Vogensen, A. Palva, and P. Varmanen. 2003. Heat and DNA damage induction of the LexA-like regulator HdiR from Lactococcus lactis is mediated by RecA and ClpP. Mol. Microbiol. 50:609-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi, J., R. Mukhopadhyay, and B. P. Rosen. 2003. Identification of a triad of arginine residues in the active site of the ArsC arsenate reductase of plasmid R773. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 227:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storz, G., and J. A. Imlay. 1999. Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Storz, G., L. A. Tartaglia, and B. N. Ames. 1990. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science 248:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun, G., E. Sharkova, R. Chesnut, S. Birkey, M. F. Duggan, A. Sorokin, P. Pujic, S. D. Ehrlich, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1374-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turgay, K., J. Hahn, J. Burghoorn, and D. Dubnau. 1998. Competence in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by regulated proteolysis of a transcription factor. EMBO J. 17:6730-6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turgay, K., L. W. Hamoen, G. Venema, and D. Dubnau. 1997. Biochemical characterization of a molecular switch involving the heat shock protein ClpC, which controls the activity of ComK, the competence transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 11:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Sinderen, D., G. Galli, P. Cosmina, F. de Ferra, S. Withoff, G. Venema, and G. Grandi. 1993. Characterization of the srfA locus of Bacillus subtilis: only the valine-activating domain of srfA is involved in the establishment of genetic competence. Mol. Microbiol. 8:833-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Sinderen, D., A. Luttinger, L. Kong, D. Dubnau, G. Venema, and L. Hamoen. 1995. comK encodes the competence transcription factor, the key regulatory protein for competence development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 15:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Sinderen, D., and G. Venema. 1994. comK acts as an autoregulatroy control switch in the signal transduction route to competence in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:5762-5770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weinrauch, Y., R. Penchev, E. Dubnau, I. Smith, and D. Dubnau. 1990. A Bacillus subtilis regulatory gene product for genetic competence and sporulation resembles sensor protein members of the bacterial two-component signal-transduction systems. Genes Dev. 4:860-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiegert, T., and W. Schumann. 2001. SsrA-mediated tagging in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:3885-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wojtkowiak, D., C. Georgopoulos, and M. Zylicz. 1993. Isolation and characterization of ClpX, a new ATP-dependent specificity component of the Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22609-22617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan, C., L. H. Lee, and L. I. Davis. 1998. Crm1p mediates regulated nuclear export of a yeast AP-1-like transcription factor. EMBO J. 17:7416-7429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng, M., F. Aslund, and G. Storz. 1998. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279:1718-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng, M., and G. Storz. 2000. Redox sensing by prokaryotic transcription factors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 59:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]