Abstract

This study examined the implications of gender attitudes and spouses’ divisions of household labor, time with children, and parental knowledge for their trajectories of love in a sample of 146 African American couples. Multilevel modeling in the context of an accelerated longitudinal design accommodated 3 annual waves of data. The results revealed that traditionality in husbands’ gender attitudes was linked to lower levels of love. Furthermore, divisions of household labor and parental knowledge moderated changes in love such that couples with more egalitarian divisions exhibited higher and more stable patterns of love, whereas more traditional couples exhibited significant declines in love over time. Finally, greater similarity between spouses’ time with their children was linked to higher levels of marital love. The authors highlight the implications of gender dynamics for marital harmony among African American couples and discuss ways that this work may be applied and extended in practice and future research.

Keywords: African Americans, development, gender roles, marital quality

Researchers have established that individuals who are married have better psychological and physical health (Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, 2007). Given that African Americans have poorer health than individuals from other racial/ethnic groups (Kung, Hoyert, Xu, & Murphy, 2008), researchers’ attention has been drawn to African American marriages and the dynamics that support their stability (Bryant et al., 2010). Prior studies have uncovered structural, cultural, and individual factors that contribute to low marriage rates for African Americans; however, less attention has been paid to understanding the reasons for the relatively high rates of marital discord and disruption (Broman, 2005; Bulanda & Brown, 2007; Faulkner, Davey, & Davey, 2005; McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2002) among African Americans who do marry (Raley & Sweeney, 2009). Thus, we currently know little about the processes that promote marital satisfaction within this group.

The larger literature on marriage documents that both gender attitudes and gendered marital dynamics are strongly linked to marital satisfaction and stability (Davis & Greenstein, 2009). This work, however, has relied on primarily European American samples. A cultural ecological perspective (García Coll et al., 1996) directs attention to the significance of sociocultural conditions, values, and practices that shape individuals’ experiences and highlights that conclusions drawn from research on European American marital processes may therefore not generalize to African American samples. Although researchers have examined gender attitudes and roles among African Americans (Kane, 2000), there is a dearth of research that has examined the impact of these factors on marital processes. Furthermore, the few available studies used ethnic comparative design to identify differences between African Americans and European Americans (e.g., Orbuch & Eyster, 1997). This research has been informative in showing that African American husbands and wives tend to share the family work and responsibilities more equally than do European American husbands and wives (Hossain & Roopnarine, 1993; John & Shelton, 1997). The question that remains to be addressed is whether more egalitarianism in gender attitudes and marital roles is linked to greater marital harmony among African Americans. An ethnic homogeneous design that focuses on factors underlying variability within an ethnic group is ideally suited to address this question (García Coll et al., 1996).

An understanding of larger sociocultural forces helps to illuminate the potential significance of gender in African American marriages. One factor is the history of African American women’s employment: Unlike European American women, married African American women have maintained an enduring presence in the workforce (J. E. Farley, 2005; R. Farley & Allen, 1987) and thus are generally satisfied about how their work and family responsibilities are woven together (Bridges & Etaugh, 1996; Collins, 2000). Like their European American counterparts, in contrast, African American men do not have a history of integrating work and family obligations (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004; Kane, 2000). Furthermore, the difficulties inherent in reconciling the traditional Eurocentric ideal of the man being the primary economic provider for his family, with the barriers to success faced by African American men, have been identified as a potential source of breakdown in African American families (S. A. Hill, 2005). Evidence of the significance of gender in African American marriages comes from one recent study showing that traditionality in husbands’ attitudes and responsibilities within the home was linked with lower marital quality (Stanik & Bryant, 2012).

The current research built on Stanik and Bryant’s (2012) study, moving from a cross-sectional sample of newlyweds to a sample of African American couples who varied widely in the duration of their marriages and were each followed longitudinally across 3 years. In addition, this study captured a range of gendered marital dynamics, including the spousal division of household responsibilities and engagement with children. Grounded in cultural ecological (García Coll et al., 1996) and developmental (Huston, 2000) frameworks and using a multilevel modeling (MLM) approach in the context of an accelerated longitudinal design, we focused on two aims. First, we described the course of marital love, as reported by both husbands and wives, from Year 3 to Year 25 of marriage. We studied love as an index of marital quality because love incorporates passion, intimacy, and commitment (Sternberg, 1986) and because it is a crucial component of marital stability (Hendrick, Hendrick, & Adler, 1988). Second, we tested whether and how spouses’ gender attitudes and gendered roles, including the divisions of housework, time with children, and parental knowledge were linked, over time, to marital love.

The Developmental Course of Marriage

Given that individuals and their roles within families continually evolve, marriage is best viewed from a developmental perspective (Huston, 2000). The small body of work that has examined African American marital processes has often focused on the early years of marriage (e.g., Orbuch & Eyster, 1997; Stanik & Bryant, 2012). Although this work has provided many insights, it may not capture the extent of change that occurs in marriage given that couples typically experience a decline in relationship quality only after the “honeymoon” phase of the relationship (Amato & Cheadle, 2005; Glenn, 1998). Although research that has examined marital trajectories among mostly European American couples has documented general patterns of decline over time (Karney & Bradbury, 1997; VanLaningham, Johnson, & Amato, 2001), much of this work has also focused on fluctuations in marital satisfaction as they are intertwined with phases of parenthood (Whiteman, McHale, & Crouter, 2007). This research has focused on couples who entered marriage without children, however, and the results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to African Americans, for whom premarital childbearing is relatively common (Landale, Schoen, & Daniels, 2010; Orbuch, Veroff, Hassan, & Horrocks, 2002).

In addressing our first aim of describing the course of marital love in African American marriages, we controlled for family structure and child age. We expected that love would be at its peak during the early, honeymoon phase of marriage and would decline significantly thereafter.

Gender Attitudes and Gendered Marital Roles

The term gender attitudes refers to individuals’ ideas about the optimal degree of similarity between the characteristics, behaviors, and activities of women versus men, including in their labor force and domestic roles. Traditional attitudes endorse a division of labor that segregates men into paid work outside the home and women into unpaid work inside the home, whereas egalitarian attitudes support a greater degree of overlap in men’s and women’s roles (McHugh & Frieze, 1997). Gender attitudes are constructed from the relevant aspects of the cultural context (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004). For African Americans, unlike other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, women have had a continuous presence in the workforce (J. E. Farley, 2005; R. Farley & Allen, 1987). This has led to a cultural norm of African American women playing a large role in providing economically for their families (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004) and is believed to contribute to African American women’s more egalitarian attitudes (Kane, 2000).

African American men, unlike their wives, tend to endorse relatively traditional values regarding home and family responsibilities (Carter, Corra, & Carter, 2009; Ciabattari, 2001). Men’s attitudes about roles within the home also stand in contrast to their more egalitarian views regarding equality for women in the workforce. These contradictory stances may arise as a response to the discrimination African American men experience outside the home and manifest themselves in men’s privileged status within the family (Rowan, Pernell, & Ackers, 1996). They may also reflect the tension between the necessity of wives’ financial support and the Eurocentric belief that earning income is the primary responsibility of the man in the family (Hill, 2005).

Given that men’s gender attitudes tend to be more nuanced and more variable compared to women’s more egalitarian ideals, recent findings on the implications of men’s attitudes for marriage are not surprising: Although newlywed wives’ attitudes are unrelated to their own or their partners’ marital satisfaction, husbands’ traditional attitudes are linked to lower levels of marital satisfaction for both partners (Stanik & Bryant, 2012). As noted, in the present study we extended this research by studying couples who ranged widely in marital duration and by exploring the implications for husbands’ and wives’ gender attitudes for longitudinal trajectories of marital love. Consistent with results from Stanik and Bryant’s (2012) study, we expected that men’s but not women’s gender attitudes would predict their own and their partners’ trajectories of marital love, such that traditionality in husbands’ attitudes would be associated with declines in love.

Given the multidimensional nature of gender (Ruble & Martin, 1998), gender attitudes may be at odds with how gender is manifested in the everyday activities that make up marital gender roles such as the division of household labor (McHale & Crouter, 1992). Furthermore, gender attitudes and gendered roles have unique implications for marital outcomes in European American families (Amato & Booth, 1995; Amato, Johnson, Booth, & Rogers, 2003; Cherlin, 1998). Accordingly, in this study we moved beyond a focus on gender attitudes to examine the implications of the gendered division of marital roles for longitudinal changes in marital love.

Theoretical discussions have held up role flexibility as strength of African American families (R. B. Hill, 1999). Indeed, relative to other racial/ethnic groups, African American husbands and wives tend to exhibit more similarity in their family responsibilities, although wives are still responsible for the lioness’s share of household labor (Hossain & Roopnarine, 1993; John & Shelton, 1997). Given that this role flexibility has often been discussed in the context of race comparative research designs, neither the variability among African American families nor the implications of this variability for African American couples’ marital quality has received much empirical attention. Stanik and Bryant (2012) found that couples’ gender role traditionality was unrelated to wives’ marital satisfaction but that traditionality in couples’ marital roles was negatively related to husbands’ marital satisfaction (Stanik & Bryant, 2012).

Building on this work, in the present study we tested whether and how variability in gender role traditionality was associated with longitudinal changes in marital love in African American marriages that varied widely in marital duration. We also extended Stanik and Bryant’s (2012) research by assessing multiple dimensions of husbands’ and wives’ marital roles, including the division of household tasks and parenting responsibilities. Although Stanik and Bryant’s results did not show links between the division of labor and wives’ reports of marital quality, we hypothesized that traditionality in marital roles would be linked to lower levels of love reported by both husbands and wives in these longer term marriages: Although women may initially be more accepting of a gendered division of labor, over time, traditionality may erode marital quality.

The Current Study

In sum, this study expanded the scope of research on African American marriage by addressing two goals. First, using an accelerated longitudinal design wherein couples who varied in marital duration were each interviewed annually for 3 consecutive years, we charted the trajectory of marital love from about Year 3 to about Year 25 of marriage and tested the hypothesis that marital love would decline as a function of marital duration. In an effort to capture the large degree of variability in family structure among African Americans, our sample included couples who married prior to having children (63%), couples who married after having children (37%), and stepparent families (22%). Although marital duration ranged from 3 to 25 years, a point of similarity was that all couples had adolescent-age offspring in the home.

Our second goal was to assess linkages between traditionality in gender attitudes and marital roles, specifically the division of household labor, time spent with children and parents’ knowledge of their children’s daily experiences, and longitudinal changes in men’s and women’s marital love. On the basis of prior research and theory on the construction of gender in African American families, we predicted that traditionality in husbands’ attitudes as well as traditionality in couples’ marital roles would be linked to declines in men’s and women’s reports of marital love. Given that both demographic characteristics and marital processes are linked to marital quality (Clements, Stanley, & Markman, 2004), and that education, family size, child age, and biological relatedness of children are related to both gender dynamics and marital outcomes (Davis & Greenstein, 2009), these factors were included as controls in all analyses.

Method

Participants

The data came from husbands and wives in 146 couples who participated in a 3-year longitudinal study of family relationships in two-parent African American families. Couples in which both partners self-identified as African American or Black and were residing with at least two adolescent-age offspring were targeted for recruitment. Two strategies were used to generate the sample in two urban centers in the mid-Atlantic region: (a) African American community members recruited about half of the sample by advertising the study in their communities, and (b) families who had been identified using a purchased marketing list were sent letters describing the study and were asked to respond by postcard or toll-free number if they were eligible and interested (McHale et al., 2006).

Of the original 202 families who participated in the first phase of the larger study, we omitted 22 couples who divorced over the course of the study, eight who were not in a couple relationship (e.g., mother and grandfather pairs), and 16 who were living together but were not married. We also omitted data from 10 couples who had been married for less than 3 years or more than 25 years because of insufficient sample size at the tail ends of the marriage-duration distribution. Of the 146 families included in the present analyses, at Time 1, mean ages of husbands and wives were 43.53 (SD = 6.23) and 40.89 (SD = 5.03), respectively. The majority of families (>80%) included two or three children, with an average family size of 4.75 (SD = 1.09), including parents. Wives’ education averaged 14.85 (SD = 1.70), and husbands’ education averaged 14.55 (SD = 2.32), with a score of 12 signifying high school graduate, 14 signifying some college, and 16 signifying a bachelor’s degree. Given the correlation between wives’ and husbands’ education (r = .45), the couple mean was included as a control. Most spouses were employed (80% of wives and 89% of husbands) and worked full-time hours (wives, M = 33.44, SD = 16.50; husbands, M = 45.04, SD = 16.89). Total family income averaged $95,172.44 (SD = $56,216.90). The average marital duration was 15.64 years (SD = 6.62).

Two children from each family also participated. Older children averaged 14.17 years (SD = 2.03), and younger children averaged 10.38 years (SD = 1.08) of age, the majority were biologically related to mothers (92% of older and 96% of younger adolescents) and fathers (81% of older and 87% of younger adolescents), and the sample was approximately equally divided by gender (51% girls) and dyad gender constellation (46% same gender). Although substantive data were not collected from children other than the targets, our analyses controlled for the age of the youngest child in the family, which on average was 9.23 years (SD = 2.80).

Procedure

The longitudinal study began in 2002, with data collected annually for 3 consecutive years. In each of the three phases, family members were interviewed individually in their homes by a team of two interviewers, almost all of whom were African American. Participants reported on relationship experiences and personal characteristics during the past year. Interviews lasted about 2 hours for parents and 1 hour for adolescents.

During the first phase, in addition to the home interview, family members were also interviewed in a series of telephone calls. This second data collection procedure was used to obtain information about spouses’ daily activities and their engagement with children. In the month following the home interview, seven telephone interviews were conducted (five on weekday evenings and two on weekend evenings) with target children. During these calls, youth reported on their daily activities and experiences outside of regular school hours. Spouses were interviewed on four of these calls and reported on their own household tasks and their experiences with their children during the day of the call. Following the completion of data collection, families received a $200 (Years 1 and 2) or $300 (Year 3) honorarium.

Measures

Marital love was assessed at all three time points with a nine-item scale from the Relationship Questionnaire (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). Using a scale that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much), and focusing on the past year, husbands and wives responded to statements such as “To what extent do you have a sense of ‘belonging’ with your partner?” Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .87 to .90.

Attitudes toward marital roles were measured at Time 1 with seven items from a measure developed by Hoffman and Kloska (1995). Using a scale that ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), husbands and wives responded to statements such as “Some equality in marriage is okay, but by and large, the man should have the main say-so.” Higher scores signified more traditional attitudes. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .82 to .84.

Division of female-typed household tasks, specifically, cooking, food preparation, laundry, and housecleaning, was measured using data from the phone calls conducted at Time 1 and was calculated as the total duration of wives’ tasks, summed across all calls, divided by the total duration of wives’ tasks plus husbands’ tasks. Higher scores signified greater traditionality (i.e., a greater proportion of household work being done by wives).

Division of parental knowledge was measured at Time 1 with the three weeknight phone calls that included mothers and the three weeknight calls that included fathers. During these calls, parents were asked to respond to eight items such as “Did your child have a writing assignment for homework today?”, and youth were later asked the same questions. Parental knowledge scores were calculated such that parents received 1 point for each item that showed agreement between themselves and their children (Crouter, MacDermid, McHale, & Perry-Jenkins, 1990). Division of parental knowledge was calculated by dividing wives’ knowledge score by wives’ knowledge score plus husbands’ knowledge score. Higher scores reflected more parental knowledge among wives (i.e., greater traditionality).

Division of dyadic time with children was measured at Time 1 using youths’ reports of their activities in the seven nightly phone calls. Youths’ reports of the time they spent in one-on-one time with each parent was summed across all days and all activities. The division of dyadic time was calculated by dividing the total duration of wives’ dyadic time with children by the sum of wives’ dyadic time plus husbands’ dyadic time with children. Higher scores reflected relatively more involvement by wives (i.e., greater traditionality).

Results

Analytic Plan

To chart the trajectory of marital love for African American couples and test whether gender attitudes and gendered marital dynamics predicted longitudinal changes in love, we estimated growth curves using MLM within our nested, accelerated longitudinal design (Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1996; Raudenbush & Chan, 1992). An MLM approach is advantageous because it extends multiple regression to accommodate clustered (i.e., nonindependent) data. In this study, time was nested within spouse, spouses were nested within couple, and couples were nested within families. Furthermore, because MLM uses maximum likelihood procedures to estimate effects, an additional benefit is that it does not require equal spacing between observations. Thus, we were able to use marital duration as the metric of time and, in doing so, we were able to estimate developmental patterns of interest that would have been obscured had we used study phase (i.e., Year 1, 2, and 3) as the time index. This feature also made it possible to maximize the utility of an accelerated longitudinal design and estimate developmental patterns that were evident over a long period of time, given that marital duration across the years of this study for couples in this sample ranged from 3 to 25 years (Duncan et al., 1996; Raudenbush & Chan, 1992). Finally, because MLM accommodates unbalanced data, it was possible to include cases with missing data (about 2%). Thus, we included all 146 couples in our analyses (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

To test our hypotheses, we estimated a series of models using SAS Proc Mixed, version 9.2. The Level 1, or within-person model, captured changes in love across time. To determine the trajectory of love over time, we tested the fit of the hypothesized linear time term relative to quadratic and cubic terms.

At Level 2, we included time-invariant predictors at the between-spouse, or within-family, level, including husbands’ and wives’ gender attitudes and spouse gender. The Level 2 model accounted for dependencies between spouses from the same couple. By including both husbands and wives in the same analysis we were able to test the moderating role of spouse gender, that is, whether the trajectory of love was different for husbands versus wives. To do this, we included the cross-level interaction between the linear time term and spouse gender. Furthermore, by including cross-level interactions between gender attitudes and the linear time term we were able to test whether the trajectory of love (i.e., extent of decline in love) differed as a function of each spouse’s gender attitudes.

Level 3 predictors were between-couple characteristics that were shared by husbands and wives and were time invariant. Here we included the measures of the gendered division of labor in Year 1, specifically, division of female-typed household tasks, division of parental knowledge, and division of dyadic parent – child time. By including cross-level interactions between the linear time term and the measures of the gendered division of labor we were able to test whether the trajectory of love differed as a function of the couples’ gendered division of labor. At Level 3, we also included all control variables, including couples’ mean education, parents’ biological relatedness to offspring, the age of the youngest child in the family, and family size.

In the case of significant interactions involving spouse gender, to test the slopes we reran the same models treating wives as the reference group (i.e., dummy coding instead of effect coding). We followed up significant interactions involving two continuous variables using procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991), distinguishing high (1 SD above the mean) versus low (1 SD below the mean) levels of the moderator variable and running separate models for spouses who were more egalitarian versus more traditional. We focused primarily on significant effects at the p < .05 level but also report trend-level effects, p < .10, when they were consistent with the study hypotheses and results from prior research. We begin with preliminary descriptive results and then turn to results pertaining to our two research aims: (a) to describe changes in love in African American marriages over time and (b) to test whether and how spouses’ and their partners’ gender attitudes and couple marital roles were linked to these patterns of change. To avoid problems associated with multicollinearity, we tested substantive predictors (gender attitudes and the three metrics of gendered division of labor) in separate models.

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for study variables are presented in Table 1. An examination of the means reveals that marital love averaged well above the midpoint on the 9-point rating scale. Furthermore, both husbands and wives reported relatively egalitarian gender attitudes. Turning to the division of household labor and parental activities, although the division of female-typed household tasks reflected a more traditional division, with wives doing more than husbands, on average, dyadic time with children and parental knowledge, in particular, were divided in more egalitarian ways.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Love | — | |||||||||

| 2. Marital duration |

−.06† | — | ||||||||

| 3. Wives’ gender attitudes |

.04 | −.003 | — | |||||||

| 4. Husbands’ gender attitudes |

−.18*** | −.03 | .27*** | — | ||||||

| 5. Division of female-typed Household labor |

−.12*** | .24*** | .10** | .20*** | — | |||||

| 6. Division of knowledge |

−.09* | .15*** | .05 | .04 | .16*** | — | ||||

| 7. Division of dyadic time |

−.09* | −.08* | −.09** | .17*** | .08* | .14*** | — | |||

| 8. Youngest child’s age |

−.11*** | .29*** | −.23*** | −.02 | −.05 | −.04 | .01 | — | ||

| 9. Family size | .08* | −.01 | .10** | .01 | .11** | −.14*** | −.11** | −.42*** | — | |

| 10. Education | −.07* | .18*** | −.08* | −.09** | .01 | .09* | −.11** | −.03 | −.06† | — |

| Mean (SD) |

7.82 (1.24) |

15.64 (6.62) |

10.79 (3.57) |

12.29 (3.74) |

0.70 (0.24) |

0.53 (0.07) |

0.63 (0.23) |

9.23 (2.79) |

4.74 (1.09) |

14.68 (1.76) |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Longitudinal Changes in Love

We conducted a preliminary series of MLMs to examine the overall growth trajectory of love. Marital duration was centered at 15.64 years, the mean marital duration across couples, across all time points. On the basis of Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion fit statistics and the significance of variance components, we found that a model with a random-intercept and fixed linear term had the best fit. On average, there was a significant decline in love as a function of marriage duration (see Table 2 for effects from all models). Neither spouse gender nor the Gender × Linear Change effect were significant predictors, indicating that this pattern of change did not differ for husbands versus wives. Biological status of children was tested as a covariate, but it was never significant and thus was removed from the final models.

Table 2.

Coefficients From Multi-Level Models Predicting Changes in Marital Love as a Function of Marital Duration, Gender Attitudes, and Marital Gender Dynamics

| Fixed effect | Unconditional model |

Model A: Attitudes |

Model B: Female- typed household labor |

Model C: Parent – child knowledge |

Model D: Parent – child dyadic time |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | |

| Intercept | 7.77*** | 0.08 | 7.76*** | 0.09 | 7.79*** | 0.10 | 7.72*** | 0.11 | 8.14*** | 0.21 |

| Level 1 | ||||||||||

| Marital duration (linear) |

−0.03* | 0.01 | −0.02† | 0 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03† | 0.02 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| Level 2 | ||||||||||

| Gender attitudes | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Gender attitudes × spouse |

−0.11** | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Level 3 | ||||||||||

| Division of female- typed household tasks |

−0.72* | 0.30 | ||||||||

| Division of feminine household tasks × linear |

−0.11* | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Division of parent – child knowledge |

−2.34 | 1.64 | ||||||||

| Division of parent – child knowledge × linear |

−0.52* | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Division of parent – child dyadic time |

−0.68* | 0.30 | ||||||||

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Attitudes Toward Marital Roles

We next tested whether and how spouses’ gender attitudes and those of their partners predicted changes in marital love. In the first model, we tested whether each spouse’s attitudes predicted his or her own reports of love, controlling for partners’ attitudes, and found a significant Gender × Attitude interaction. Follow-ups revealed that husbands with more traditional attitudes reported lower levels of love, on average (γ = −0.11, SE = 0.02, p < .05). In contrast, wives’ attitudes were unrelated to their own reports of marital love. There were no significant unique effects of partners’ attitudes and no interactions involving time (marital duration).

Gender Roles in Marriage

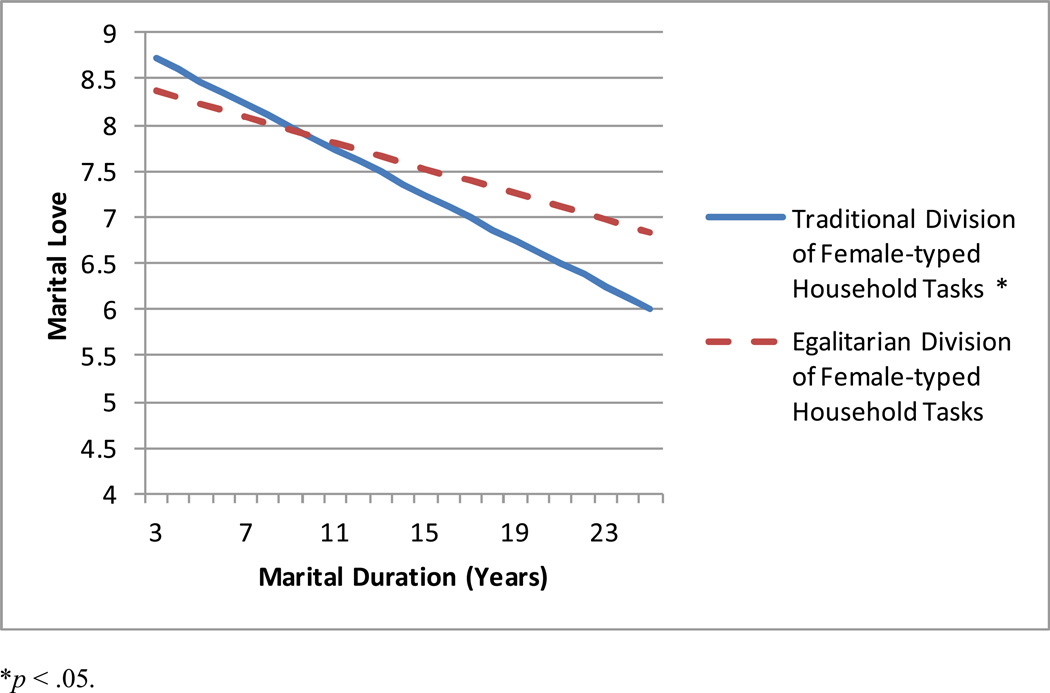

We next tested whether and how gendered marital roles predicted changes in marital love. Beginning with the division of female-typed household labor, a significant interaction with the linear time term emerged. Follow-up tests revealed that, for couples in which wives spent relatively more time in housework than husbands, marital love declined over time (γ = −0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05); in contrast, for more egalitarian couples, reports of love did not change over time (γ = 0.01, SE = 0.02, p > .05; see Figure 1). A significant interaction also emerged between the division of parental knowledge and the linear time term. Again, follow-up tests indicated that, for couples in which wives exhibited relatively higher levels of parental knowledge than husbands, marital love declined over time (γ = −0.52, SE = 0.25, p < .05); when spouses were more similar in their levels of parental knowledge, reports of love did not change over time (γ = −0.003, SE = 0.02, p > .05). Finally, in the case of the division of dyadic time with children, a significant main effect indicated that more egalitarian parental roles were linked to higher average levels of marital love, and there was no interaction with time.

Figure 1.

Interaction Between Linear Effect of Marital Duration and Division of Female-Typed Household Tasks for Change in Marital Love.

Discussion

African Americans experience high rates of marital discord and dissolution (Broman, 2005; Bulanda & Brown, 2007; Faulkner et al., 2005; McLoyd et al., 2002; Raley & Sweeney, 2009). Given that they also experience relatively poor physical and mental health compared to other segments of the population (Kung et al., 2008), and in light of the well-established positive link between marriage and health (Proulx et al., 2007), researchers have called for work exploring African American marriage and the processes that promote its quality and stability (Bryant et al., 2010). Using data from a unique 3-year longitudinal study of African American families, this research reflects a step toward answering this call. Furthermore, this work extends findings by Stanik and Bryant (2012) that provided preliminary evidence suggesting gender attitudes and roles are a central component of marital well-being among African Americans. Our results revealed an overall significant linear decline in love as a function of couples’ martial duration. Gender roles moderated this decline such that couples with more traditional roles in their division of time in female-typed household tasks and parental knowledge experienced a significant decline in love, whereas reports of love from couples with egalitarian roles in these domains remained stable over time. In addition, similarity in the amounts of time husbands and wives spent with their children was positivity related to couples’ reports of love. Furthermore, traditionality in husbands’ gender attitudes was negatively related to their own, but not their wives, reports of love. Below we discuss these findings in greater detail, highlighting the ways in which this study advances understanding of African American marriages.

The Developmental Course of Marriage

Previous studies that have examined the course of marital quality as a function of marital duration have relied on mostly European American samples and couples in the early years of marriage, or have used cross-sectional designs (Karney & Bradbury, 1997; Orbuch & Eyster, 1997; Stanik & Bryant, 2012; Whiteman et al., 2007). Given the role of sociocultural forces in African American marriages (Bryant et al., 2010) and the fact that marital quality often declines after the honeymoon phase (Amato & Cheadle, 2005; Glenn, 1998), this research answers the call of cultural ecological (García Coll et al., 1996) and developmental researchers (Huston, 2000) to examine marital processes in a longitudinal, ethnically homogeneous sample of African American couples. Consistent with findings from past research on marital satisfaction, patterns of marital love in African American couples followed a gradual but significant decline from Year 3 to Year 25 of marriage.

Identifying the linear decline in marital love is an initial step in research on the marriages of African Americans. Building on this work, one crucial next step is to explore the role of family structure on trajectories of marital love for African American couples. Well over half of African American families enter marriage with children, and about half of all African American parents have children with more than partner (Martin et al., 2010). Strain from not having a marital foundation in place before the birth of a child (Orbuch et al., 2002), or from negotiating coparenting roles in a stepparent family, may have both immediate consequences for the marital quality of new partners and long-term consequences for marital stability and satisfaction. Although the current sample represented many family structures, the size of the sample limited our ability to make comparisons between these different structures. Furthermore, research with European American couples who entered marriage before the birth of their first child has revealed linkages between child development and marital quality (Whiteman et al., 2007). Given these linkages, another future direction in this area of study should be to explore interactions among marital duration, developmental phase, and family structure in an effort to illuminate how these factors contribute to marital discord and dissolution among African Americans.

Gender Attitudes, Gender Role Dynamics, and Marital Love

The second aim of this research was to uncover whether and how gendered individual and marital qualities were related to variability in marital love among African American couples over time. Prior research has identified that although African American spouses have more flexible gender roles (Hossain & Roopnarine, 1993; John & Shelton, 1997), men’s gender attitudes remain more traditional both relative to African American women and compared to the actual division of husbands’ and wives’ family obligations (Carter et al., 2009; Ciabattari, 2001). Little work, however, has examined the implications of these attitudes and roles for marital quality among African Americans. By relying on a longitudinal sample of African American couples raising adolescent-age children, the current work extended that of Stanik and Bryant (2012) who, using a cross-sectional sample, provided initial evidence that gender may contribute to marital satisfaction among newly married African American couples.

Beginning with gender attitudes, and in partial support of our hypothesis, traditionality in husbands’ attitudes was negatively associated with their own reports of marital love. In contrast to our expectations, traditionality in husbands’ attitudes was not significantly related to wives’ reports of marital love. The partner effect of husbands’ attitudes on wives’ marital quality previously found by Stanik and Bryant (2012) may be specific to a newlywed sample, for two reasons. First, it could be that, as marriages endure, husbands’ behavior is more important to their wives’ marital quality than their attitudes; second, perhaps marriages in which wives are most troubled by their husbands’ attitudes do not make it out of the honeymoon phase. More research that examines the consequences of traditionality in African American men’s attitudes is warranted. For instance, it may be that when the division of labor does not align with men’s expectations, marital conflict arises. Spouses’ dissatisfaction may also lead to the seeking out of alternative partners. Finally, because some men may be better than others at reconciling their desire for traditional family roles with economic and sociocultural realities, potential moderators between men’s gender attitudes and their reports of marital quality should be identified.

Turning to gendered marital dynamics, we found, consistent with our predictions, that husbands and wives who were more similar in the amount of time they spent on female-typed household tasks and in their parental knowledge exhibited stable patterns of love over time. In contrast, husbands and wives with more traditional roles experienced significant declines in love. Although division of time with children did not moderate the trajectory of love, husbands and wives who spent more similar amounts of time with their children reported higher levels of love, on average, than those with a more traditional division of time with children. Given that African American men and women have historically experienced more overlap in their family roles (Hossain & Roopnarine, 1993; John & Shelton, 1997), violations of this cultural norm may result in lower marital quality. Because our research examined the divisions of roles only within the home, another avenue for research is to explore how the division of the economic-provider role between African American spouses contributes to marital satisfaction and stability. Furthermore, given the achievement gap between African American men and women (Hefner, 2004), another area for investigation is whether and how differences between husbands’ and wives’ economic and social capital, including education, income, and job prestige, manifest in gendered marital dynamics and affect marital outcomes.

In the face of the many strengths and contributions of our study, there are several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, our small sample was geographically circumscribed and relatively high in income and education, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, we relied on an accelerated longitudinal design to examine the developmental course of marital love rather than following each couple across several decades. An advantage of our design is that it allows long-term trajectories to be estimated on the basis of data collected over a relatively short period of time, toward feasibility and efficiency (Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1996; Raudenbush & Chan, 1992). Just as true longitudinal studies suffer from cohort effects (i.e., generalizations are made from data collected on marriages that took place at a single point in time), so too might a particular cohort in our study fail to adequately represent a particular time point in the course of marriage (Glenn, 1998). It is important to note, however, that an accelerated longitudinal design moves toward minimizing the confound between date of marriage and duration of marriage that characterizes a true longitudinal study. Third, our results are limited by our reliance on one index of marital quality. Future research should consider how marital gender dynamics are related to dimensions such as marital conflict, infidelity, and divorce. Finally, the developmental scope of our findings is limited given that all couples were raising adolescent-age children at the time of data collection. Our small sample led us to target a relatively homogeneous group of marriages but failed to capture important periods of change, such as the transitions to parenthood or an empty nest, which may have important implications for both gendered dynamics and marital quality.

Despite these limitations, this study enhances our understanding of the developmental course of marital love, in addition to the linkages among gender attitudes, gender roles, and marital love among African American couples. In general, our results speak to the growing body of work on normative processes within African American couples. Our findings may also be useful in applied contexts. For instance, practitioners should be alerted to the possibility that husbands’ gender attitudes and spouses’ family roles may be sources of tension for African American couples. Furthermore, interventionists might consider directing efforts toward helping African American couples distribute their family obligations in a more egalitarian manner. Finally, at the broadest level, this work illustrates that applying cultural ecological and developmental frameworks to the study of African American couples can lead to a more nuanced understanding of relationship functioning within this group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01-HD32336-02 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale (Principal Investigators). We thank project staff and graduate students who helped conduct this study and participating families for their time and insights into their lives.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A. Changes in gender role attitudes and perceived marital quality. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Cheadle J. The long reach of divorce: Divorce and child well-being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Johnson DR, Booth A, Rogers SJ. Continuity and change in marital quality between 1980 and 2000. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bolzendahl CI, Myers DJ. Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men 1974 – 1998. Social Forces. 2004;83:759–790. [Google Scholar]

- Braiker HB, Kelley HH. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess R, Huston T, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges JS, Etaugh C. Black and White college women’s maternal employment outcome expectations and their desired timing of maternal employment. Sex Roles. 1996;35:543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Marital quality in Black and White marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;26:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Wickrama KAS, Bolland J, Bryant BM, Cutrona CE, Stanik CE. Race matters even in marriage: Identifying factors linked to marital outcomes for African Americans. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010;2:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda JR, Brown SL. Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research. 2007;36:945–967. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JS, Corra M, Carter SK. The interaction of race and gender: Changing gender-role attitudes, 1974 – 2006. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90:196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ciabattari T. Changes in conservative men’s gender ideologies: Cohort and period influences. Gender & Society. 2001;15:574–591. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Marriage and marital dissolution among Black Americans. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;39:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Clements ML, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Before they said “I do”: Discriminating among marital outcomes over 13 years. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:613–626. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, MacDermid SM, McHale SM, Perry-Jenkins M. Parental monitoring and perceptions of children’s school performance and conduct in dual-earner and single-earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SN, Greenstein TN. Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Hops H. Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Farley JE. Majority – minority relations. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Farley R, Allen A. The color line and the quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RA, Davey M, Davey A. Gender-related predictors of change in marital satisfaction and marital conflict. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2005;33:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Garcia HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND. The course of marital success and failure in five American 10-year marriage cohorts. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Hefner D. Where the boys aren’t: The decline of Black males in colleges and universities has sociologists and educators concerned about the future of the African American community. Black Issues in Higher Education. 2004;21:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS, Hendrick C, Adler NL. Romantic relationships: Satisfaction, and staying together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:980–988. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RB. The strengths of African American families: Twenty-five years later. Lanham, MD: University Press of America; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hill SA. Black intimacies: A gender perspective on families and relationships. Walnut Creek, CA: Rowman Alta Mira Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LW, Kloska DD. Parents’ gender-based attitudes toward marital roles and child rearing: Development and validation of new measures. Sex Roles. 1995;32:273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Z, Roopnarine JL. Division of household labor and childcare in dual-earner African-American families with infants. Sex Roles. 1993;29:571–583. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL. The social ecology of marriage and other intimate unions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:298–320. [Google Scholar]

- John D, Shelton BA. The production of gender among Black White women and men: The case of household labor. Sex Roles. 1997;36:171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kane EW. Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1075–1092. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2008;56:4–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Schoen R, Daniels K. Early family formation among White, Black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;1:445–474. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09342847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Kirmeyeer S, Osterman MJK. Births: Final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2010;58:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC. You can’t always get what you want: Incongruence between sex-role attitudes and family work roles and its implications for marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:537–547. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim J, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, Swanson DP. Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77:1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh MC, Frieze IH. The measurement of gender-role attitudes: A review and commentary. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, Eyster SL. Division of household labor among Black couples and White couples. Social Forces. 1997;76:301–332. [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, Veroff J, Hassan H, Horrocks J. Who will divorce: A 14-year longitudinal study of Black couples and White couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CM, Helms HM, Buehler C. Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:576–593. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Sweeney MM. Explaining race and ethnic variation in marriage: Directions for future research. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1:132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Chan WS. Growth curve analysis in accelerated longitudinal designs. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1992;29:387–411. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan GT, Pernell EJ, Ackers TA. Gender role socialization in African American men: A conceptual framework. Journal of African American Men. 1996;1:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL. Gender development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 933–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Stanik CE, Bryant CM. Marital quality of newlywed African American couples: Implications of egalitarian gender role dynamics. Sex Roles. 2012;66:256–267. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review. 1986;93:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, Amato P. Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces. 2001;79:1313–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Longitudinal changes in marital relationships: The role of offspring’s pubertal development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1005–1020. [Google Scholar]