Abstract

The way romantic partners behave during conflict is known to relate to stress responses, including activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis; however, little attention has been paid to interactive effects of partners’ behaviors, nor to behavior outside of marital relationships. This study examined relations between unmarried partners’ negative and positive behaviors during discussion of conflict and their HPA responses, including both main effects and cross-partner interactions. Emerging adult opposite-sex couples (n=199) participated in a 15-minute conflict discussion and afterward rated their behavior on 3 dimensions: conflictual, holding back, and supportive. Seven saliva samples collected before and after the discussion were assayed for cortisol to determine HPA response. Quadratic growth models demonstrated associations between male x female partners’ behaviors and cortisol trajectories. Two negative dyadic patterns—mutual conflictual behavior (negative reciprocity); female conflictual/male holding back (demand-withdraw)—and one positive pattern—mutual supportive behavior—were identified. Whereas negative patterns related to lower cortisol and impaired post-discussion recovery for women, the positive pattern related to lower cortisol and better recovery for men. Women’s conflictual behavior only predicted problematic cortisol responses if their partner was highly conflictual or holding back; at lower levels of these partner behaviors, the opposite was true. This work demonstrates similar costs of negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw and benefits of supportive conflict dynamics in dating couples as found in marital research, but associations with HPA are gender-specific. Cross-partner interactions suggest behavior during discussion of conflict should not be categorized as helpful or harmful without considering the other partner’s behavior.

Keywords: Couples, HPA, Cortisol, Conflict Behavior, Demand-Withdraw, Hierarchical Linear Modeling

1

There is a growing recognition that the way in which people handle daily stressors matters for their health and well-being [1, 2, 3, 4], yet studies examining responses to common naturalistic stressors remain sparse. Couples’ behavior during discussion of conflict—especially patterns involving mutual negativity or demand-withdraw dynamics—is known to be a potent predictor of mental and physical health problems, but further study is needed to determine why (i.e., physiological mechanisms) and when a particular behavior pattern could be most harmful for male vs. female partners. In addition, couples behavior-physiology links prior to marriage have received little attention. In this paper, we examine associations between young romantic partners’ behaviors during a discussion of unresolved conflict and their neuroendocrine responses to show how behavior translates into physiology in a commonly encountered interpersonal stress context.

Couples’ behavioral patterns during discussion of conflict are bidirectionally related to distress and poor health [5, 6, 7], making a clear understanding of how and why particular behaviors harm partners a priority for health promotion efforts. Typically, partners who are able to support one another and maintain positive engagement during discussion of conflict are protected from potential harm, whereas those who rely on negative hostile or aggressive behaviors suffer more adverse consequences, from relationship distress to depression and physical illness [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. In addition, a demand-withdraw dynamic in which one partner engages in the discussion while the other disengages has been identified and related to poor relationship and personal outcomes [14, 15, 16]. Thus, couples’ behavior during conflict may be categorized as (a) unlikely to cause harm—mutually positive behavior, or (b) likely to cause harm—negative reciprocity or demand-withdraw behaviors. Though these couple-level categorizations are well established, evidence for gender differences highlights the need to approach behavior at the level of individual partners.

Women, compared to men, are typically both more responsible for and responsive to the quality of couples’ conflict resolution. For example, a longitudinal study following a mix of unmarried and married couples across 10 years demonstrated that negative patterns during discussion of conflict—characterized by one or both partners’ psychological aggression—related more strongly to women’s depression and relationship satisfaction; at the same time, women’s positive engagement during discussions had a unique positive association with both their own and their partners’ satisfaction [9, 10]. This suggests that whereas both partners’ negative behaviors should be most harmful for women, positive partner behaviors should be most helpful for men. The demand-withdraw pattern also shows clear gender differences; women typically take on and show costs of the demanding role, whereas men more often take the withdrawing role, and may actually be reinforced for such disengagement [17, 18, 19]. It has been suggested that these gender-specific vulnerabilities derive from lingering power differentials—i.e., men enjoying more power in intimate relationships—and from the differential importance of cultivating harmonious relationships inherent in masculine vs. feminine gender role prescriptions [20]. Regardless of the reasons for these differences, it is clear that men and women can expect to benefit or suffer from different variants of the behavior patterns described. What is less clear, but important for those hoping to improve couples’ health, is how these patterns shape physiological stress.

A potential link in the chain from couples’ conflict to poor health is dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the neuroendocrine system responsive to psychological stress whose end product is the steroid hormone cortisol. There is ample evidence for relations between dysregulated HPA responses and both mental health problems (i.e., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress; 21, 22) and somatic complaints (i.e., metabolic syndrome, autoimmune disease; 23, 24, 25). Both elevated and suppressed cortisol responses may reflect dysregulation, as shown by research relating different symptom patterns to stress hyper- vs. hyporesponse, but delayed recovery following stress more consistently signals problems [26, 27, 28]. Gender may also condition the interpretation of a “regulated” cortisol response; previous work within the current sample showed that whereas depressed women had lower cortisol levels during discussion of conflict and delayed post-discussion recovery, depressed men had higher cortisol levels both before and after the discussion [29]. This means that an interpretation not only of harmful behaviors, but also of harmful HPA responses, should be qualified by partner gender. Although some research has linked the two, a tendency to collapse across partners’ behaviors and to assume a single standard of HPA regulation means there is still considerable ambiguity about gender-specific paths from behavior during conflict to maladaptive stress responses.

A number of studies of married couples have revealed associations between behaviors during discussion of conflict and HPA, though there is inconsistent evidence for which behaviors are most problematic, and which component/s of HPA reactivity and recovery are affected. For example, previous research has shown mutually negative behaviors to relate to both increasing cortisol across a conflict discussion session [30] and reduced cortisol responses to the discussion [31] among wives. Other studies have demonstrated relations between wives’ positive behaviors and their own cortisol recovery following discussion of conflict [32], and a relation between perceived (but not observed) wife demand-husband withdraw sequences and elevated cortisol at the end of the discussion [33]. Together, these studies support the notion that positive behaviors can help, and negative behaviors and/or demand-withdraw can harm, wives’ HPA regulation, but finding these associations depends on how cortisol responses are analyzed (i.e., examining absolute levels before or after discussion of conflict vs. pre-discussion reactivity and post-discussion recovery slopes).

Another issue requiring clarification is whether these same relations hold for unmarried couples just building a committed relationship, which could yield important targets for early intervention. There is some evidence that wives (compared to unmarried cohabiting women) suffer more adverse impacts of negative couples’ behaviors, whereas husbands (compared to unmarried cohabiting men) suffer less [34]. This implies that the gender-specific behavior relations identified in married couples may be attenuated or even absent in unmarried couples. At the same time, research in adolescent couples suggests young partners may be especially susceptible to both the negative and positive patterns identified in more established relationships. In particular, young women’s sensitivity to issues of power and control may heighten the impact of conflictual or aggressive behaviors, young men’s autonomy-seeking needs may make withdrawal a particularly important release (even as it frustrates their partners), and both young partners’ reliance on emotional support may enhance the value of supportive behaviors [35–37]. Thus, we might expect unmarried emerging adult couples to show either weaker (though probably in the same direction) or stronger associations with these behaviors, compared to their marital counterparts. Determining which is the case would help to determine whether early couples interventions are warranted, and if so, what they should target. A final important unanswered question in this research is how male and female partners’ individual behaviors work together—cross-partner interactions rather than a summary across partners—to impact stress.

1.1 The Current Study

From the above research, we can conclude that women tend to be especially vulnerable to couples’ negative interaction patterns; that high or low HPA activity, but especially nonrecovery following discussion of conflict, should be problematic; and that both partners’ behaviors should be taken into account when assessing regulation. However, more information is needed about the separate contributions of each partner’s behavior in the context of the other (cross-partner interactions) and relations with distinct aspects of HPA responses (acute pre-discussion reactivity and post-discussion recovery components, as well as activation levels during discussion of conflict). Finally, little is known about the correlates of these behaviors among younger, unmarried couples. Relying on evidence from marital conflict discussions may obscure or exaggerate vulnerabilities of men and women in non-marital relationships.

This study was designed to address these gaps by testing associations between self-rated behaviors—conflictual behavior, holding back, and supportiveness—and cortisol responses to discussion of unresolved conflict in a sample of young unmarried couples. Both main effects of each partner’s behaviors and cross-partner interactions were considered, and cortisol responses were represented by quadratic growth models centered at different time points to separately examine pre-discussion reactivity, discussion stress, and post-discussion recovery components. Based on the evidence reviewed above, we hypothesized that mutual positive behavior (high supportiveness, especially on the part of female partners) would predict regulated cortisol responses, whereas negative reciprocity (high conflictual behavior on the part of both partners) and demand-withdraw (high female partner conflictual behavior paired with high male partner holding back) would predict dysregulated responses. Given previous gender difference findings, we hypothesized that women would generally show stronger associations between behaviors and stress physiology. We based judgments of gender-specific “dysregulation” on previous findings in the current sample relating women’s distress to low cortisol and delayed recovery, and men’s distress to high cortisol. Thus, we predicted that behavioral patterns identified as “harmful” would relate to the former profile for female partners, and to the latter for male partners.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Opposite-sex emerging adult couples (n = 199 couples; M age = 19.24, SD = .78 years) were recruited to participate in a study of romantic relationships. To be eligible, partners had to be between 18 and 21 years old, and to have been in the current relationship for 2 months or more. Reflective of the community from which they were drawn, participants were mostly European-American (87%) and had completed some college (96%). Most couples were either in an exclusive dating relationship (48.3%) or a long-term committed relationship (46.7%), though several reported they were in a nonexclusive dating relationship (4.5%) or engaged (.5%). The median length of the relationship was approximately 1 year (26% 2–6 months, 19.5% 7–12 months, 36% 1–2 years, 9.5% 2–3 years, 9% > 3 years).

2.2 Procedures

Data for this study were collected during a 2-hour laboratory session in which partners completed self-report questionnaires, contributed saliva samples for cortisol assay, and participated in a conflict discussion task. All sessions began at 4pm to control for diurnal variations in cortisol, and participants were instructed to avoid activities that could compromise saliva assays (i.e., using alcohol or illegal drugs, or dental work within 24 hours of the session; eating, drinking, smoking, or brushing teeth within 2 hours). If any of these conditions had been violated, or if a participant had an elevated temperature at the start of the session, the couple was rescheduled to return at another date.

After completing an initial set of questionnaires, participants were given a full description of the conflict task. Each partner was asked to identify a topic that had been a source of heated and unresolved debate within the past month, and one topic was selected via coin toss to randomize which partner’s topic (male-nominated or female-nominated) was discussed. Partners were given 15 minutes alone in a room to attempt to resolve the chosen issue. The discussion was continuously videotaped, and afterward a researcher edited the video with FinalCutPro. For all couples, the middle 8.5 minutes of the discussion was edited to create a series of 34 15-second segments separated by 15-second segments of blank screen to present for behavior ratings. Immediately after the discussion, participants continued with a series of computer-based questionnaires (assessing variables not used in the current study) until the saliva sampling period was completed, or 1 hour post-discussion. Then, participants watched the edited video and rated both their own and their partner’s behavior during each segment (see below for behavior rating scales). Seven saliva samples were collected over the course of the session to assess HPA trajectories leading up to and following conflict. Participants passively drooled down a straw into a plastic vial, which was then sealed and frozen for storage at −20 C until shipment to Salimetrics, LLC for cortisol assay. Sample timing was dictated by the 15–20 minute lag for peak stress to be reflected in salivary cortisol. The first sample, collected soon after participants arrived at the session, represented partners’ stress level upon entry, or response to the general task of participating in a psychological study. The second sample, collected 15 minutes after the description of the conflict discussion task, represented anticipatory stress. The third sample, collected 10 minutes discussion completion, represented stress during the discussion itself. Remaining post-task samples were collected 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after the discussion, representing post-task recovery.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Conflict behaviors

Participants rated both their own and their partner’s behavior on a series of dimensions derived from previous interpersonal conflict research (see 38 for a full description of and justification of the rating method—as shown in 37, self-ratings of behavior, as opposed to observer ratings, may be especially relevant to partners’ well-being; see also 39 for an example using this rating method). Participants were shown their video-taped discussion, which was paused automatically every 15 seconds by a computer to allow them time to rate each dimension for the previous 15-second segment. Participants were asked to “not rate how you feel now watching the tape, but try to relive or re-experience how you felt during the discussion.” Participants were given 4 segments to ‘practice’ the rating procedure and ask questions about the procedure before rating the rest of their discussion. The dimensions of interest for the current study, based on convergence with prior marital research, included (1) conflictual (implying negative and/or demanding behavior), (2) holding back (implying withdrawal), and (3) supportive (implying positive behavior). Use of each behavior was rated on a 5-point scale from 0=not at all to 4=very much so. Stability in self-rated behaviors across the 34 individual segments (Cronbach’s alpha = .96 for conflictual, .97 for holding back, and .98 for supportive) confirmed that averaged scores could be meaningfully interpreted. Standardized (Z) scores were used in analyses to provide a common centered metric.

2.3.2 HPA response (salivary cortisol)

Saliva samples were assayed for cortisol using an enzyme immunoassay with a range of sensitivity .007–1.12 μg/dl, average intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation 4.13% and 8.89%, respectively. All samples were assayed in duplicate, and average scores used in analyses. Samples were also tested for blood contamination, which can falsely elevate analyte levels.

2.3.3 Control variables

Factors that could impact cortisol values were assessed and considered as possible controls in analyses. Besides blood contamination, these included medication use, sleep/wake times, and season. In addition, characteristics of the relationship such as commitment status, length of time together, and topic (his or hers) of discussion were considered. Variables found to relate to partners’ cortisol levels (i.e., blood contamination) were included as covariates in analyses.

2.4 Analytic Approach

A multilevel modeling framework was used to account for the dependency of multiple cortisol scores measured over time within couples. This approach separates observed variance into within-couple (Level 1) and between-couple (Level 2) components, allowing for more accurate standard error estimates. At Level 1, both partners’ cortisol response trajectories were captured with quadratic growth models centered at (1) the initial sample to test pre-discussion cortisol levels and slopes, (2) the third sample to test discussion cortisol levels and slopes, and (3) the sixth sample to test post-discussion cortisol levels and slopes. The quadratic component of each model offered information about partners’ overall reactivity/recovery dynamics (i.e., a more peaked vs. flatter response curve). At Level 2, differences across couples in these trajectory parameters could be explained by their behaviors during the discussion—his, hers, and his x her behavior. An example of the two-level equation is given below:

Level 1

Level 2

Men’s and women’s cortisol levels at the given centering point are represented by β0 and β3, instantaneous rate of change at that centering point by β1 and β4, and overall response dynamics by β2 and β5. Main effects of his and her behaviors on these parameters are represented by γ1 and γ2, and the cross-partner interaction effect by γ3. Three sets of Level 2 behavior predictors were tested in separate models to address study hypotheses: (1) male x female partner conflictual (negative reciprocity), (2) male hold back x female conflictual (demand-withdraw), and (3) male x female partner supportive (mutual positive).

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Analyses

Means and standard deviations for men’s and women’s self-rated behaviors (means across video segments) are given in Table 1. None of the cross-partner behavior ratings (i.e., his rating of her behavior and vice versa) were found to predict cortisol, so these are not discussed further. Thus, all analyses below are based on partners’ self-ratings of their own behaviors.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Male and Female Partners’ Behaviors

| Males M, SD |

Females M, SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Conflictual | 1.54, .79 | 1.49, .83 |

| Holding Back | .88, .75 | .68, .73 |

| Supportive | 1.74, .88 | 1.63, .96 |

Note. Significant gender difference found for self-rated holding back, t(188) = 3.00, p < .01.

T-tests comparing men vs. women revealed only one significant difference; male partners reported holding back more, on average, than their female counterparts, t(188) = 3.00, p < .01. Correlations among partner behaviors showed cross-partner concordance for each of the 3 behavior dimensions, but especially for conflictual behavior (see Table 2). Within partners, conflictual behavior related positively to holding back, especially among men, and it additionally related to lower supportive behavior among women only. These associations supported previous indications that holding back could be especially problematic when men used it and conflictual behavior especially problematic when women used it (see 40, which related partners’ behaviors to self-reported depressive symptoms).

Table 2.

Correlations among Male and Female Partners’ Behaviors

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M Conflictual | |||||

| 2. M Holding Back | .37** | ||||

| 3. M Supportive | −.08 | .04 | |||

| 4. F Conflictual | .53** | .26** | −.16* | ||

| 5. F Holding Back | .29** | .26** | .05 | .24** | |

| 6. F Supportive | −.21** | −.12 | .34** | −.31** | −.05 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01

Of the topics discussed, 32% had been nominated by the male partner only, 36% by the female partner only, and 32% had been nominated by both partners. Topic choice did not relate directly to partners’ cortisol trajectories, nor did it act as a moderator of behavior relations with cortisol, so it was not included in the models reported below.

3.2 Multilevel Modeling: Baseline Models

First, baseline models with no Level 2 predictors were fit to describe average male and female partner cortisol trajectories. The cortisol outcome was natural log-transformed to correct for positive skew. Whereas partners’ cortisol intercepts tended to be positively associated within couples (τ correlations = .24–.32 across centerings), neither their slopes nor quadratic components were associated (τ = −.03 and −.02, respectively). Models revealed a significant pre-discussion reactivity slope, on average, for women only (b = .21, SE = .06), and significantly declining slopes for both men and women at the discussion (b = −.28, SE = .02 and b = −.12, SE = .02, respectively) and post-discussion (b = −.55, SE = .05 and b = −.35, SE = .04, respectively) time points. Both partners showed a significant overall response curvature (b = −.22, SE = .04 for men; b = −.19, SE = .03 for women). Men had higher cortisol intercepts overall (χ2[2] = 2003.15–2690.12, p < .001); lower pre-discussion slopes (χ2[2] = 13.59, p < .01), but steeper discussion (χ2[2] = 164.02, p < .001) and post-discussion (χ2[2] = 202.30, p < .001) slopes; and more peaked overall response curves (χ2[2] = 76.50, p < .001), compared to women. At the same time, significant between-couple variability in each of these parameters suggested meaningful differences that could be explained by adding behavior predictors.

3.3 Multilevel Modeling: Explanatory Models

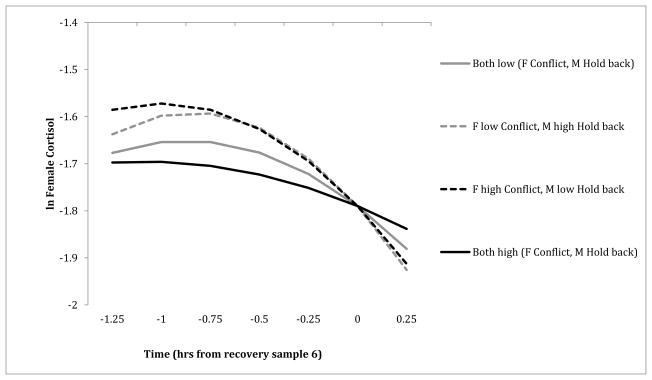

The first set of models—designed to test the impact of negative reciprocity on partners’ stress responses—demonstrated an association between male x female partners’ conflictual behavior and women’s cortisol levels before, during, and after the discussion, as well as a trend-level association with women’s post-discussion slopes and overall response curves (see Table 3, panel A). Further examination of the interaction results suggested that a pattern of mutual high conflict related to lower women’s cortisol levels and delayed post-discussion recovery. Probing predicted associations at high and low values of partner behavior showed that women’s high conflictual behavior predicted lower cortisol levels and flattened recovery slopes only if their partner was also relatively high on conflictual behavior. At low levels of mutual conflictual behavior, women also showed low, flat cortisol trajectories, suggesting a lack of engagement in the discussion1. Figure 1 displays expected women’s cortisol trajectories, plotted at high (+1) and low (−1) levels of their own and their partners’ conflictual behavior. Contrasts of model coefficients confirmed that the male x female partner conflictual term related more strongly to women’s than to men’s cortisol levels, χ2(2) = 6.23 before the discussion, 6.90 during the discussion, p < .05 (gender differences in the post-discussion model did not reach significance).

Table 3.

Relations Between Male and Female Partners’ Behaviors and Women’s Cortisol Trajectories

| Model Predictors | Pre-Discussion | Discussion | Post-Discussion | Overall Response | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Curvature | ||||||||

| Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | |

| A. Negative Reciprocity | ||||||||||||||

| F Conflictual | .003 | .94 | −.082 | .34 | −.036 | .53 | −.006 | .82 | −.024 | .66 | .045 | .38 | .043 | .32 |

| M Conflictual | .083 | .03 | .032 | .58 | .097 | .04 | −.0002 | .99 | .091 | .07 | −.022 | .60 | −.018 | .55 |

| F x M Conflictual | −.092 | .02 | −.084 | .16 | −.12 | .008 | .013 | .51 | −.096 | .05 | .077 | .06 | .055 | .08 |

| B. Demand-Withdraw | ||||||||||||||

| F Conflictual | .028 | .50 | −.077 | .34 | −.007 | .89 | −.004 | .87 | .004 | .93 | .045 | .34 | .041 | .30 |

| M Hold Back | .006 | .89 | −.003 | .96 | .011 | .82 | .015 | .57 | .024 | .62 | .027 | .50 | .010 | .72 |

| F Conflictual x M Hold Back | −.096 | .02 | −.068 | .25 | −.11 | .02 | .035 | .23 | −.070 | .12 | .104 | .02 | .059 | .04 |

| C. Positive Reciprocity | ||||||||||||||

| F Supportive | −.020 | .60 | −.054 | .38 | −.054 | .22 | −.025 | .26 | −.063 | .14 | −.005 | .89 | .017 | .58 |

| M Supportive | .033 | .38 | .073 | .21 | .067 | .15 | .004 | .85 | .056 | .24 | −.042 | .26 | −.039 | .17 |

| F x M Supportive | −.016 | .62 | −.016 | .74 | −.017 | .66 | .013 | .51 | −.004 | .92 | .032 | .33 | .016 | .49 |

Note. p < .05 indicated in bold; p < .10 indicated in bold italics.

Figure 1.

Female and male partner conflictual behaviors interact to predict women’s cortisol.

Note. Relations with recovery slope and quadratic term are marginal (p < .10)

The second set of models—designed to test the impact of demand-withdraw dynamics on partners’ stress responses—showed links between male partner holding back x female partner conflictual behavior and women’s cortisol levels before and during the discussion and post-discussion slopes, as well as their overall response curves (see Table 3, panel B). The combination of high male partner holding back and high female partner conflictual behaviors, reflective of demand-withdraw, related to lower women’s cortisol and increasing cortisol (rather than recovery) following the discussion. By contrast, in the context of low partner holding back, high levels of women’s conflictual behavior related to higher cortisol and more rapid recovery. Figure 2 illustrates expected women’s cortisol trajectories, plotted at high (+1) and low (−1) levels of their own conflictual behavior and their partners’ holding back. Contrasts of coefficients showed stronger associations between the male holding back x female partner conflictual term and women’s (compared

Figure 2.

Female partner conflictual behavior and male partner holding back interact to predict women’s cortisol.

Relations were also found between male partner holding back x female partner conflictual behavior and men’s pre-discussion slopes and cortisol levels during and after the discussion, as well as their overall response curves (see Table 4, panel B). In contrast to the above relations with women’s cortisol, the combination of high male partner holding back and high female partner conflictual behavior appeared neutral or even protective for men’s discussion-related reactivity; women’s high conflictual behavior predicted increased partner pre-discussion reactivity and higher discussion cortisol only if men did not hold back. Figure 3 shows expected men’s cortisol trajectories, plotted at high (+1) and low (−1) levels of their own holding back and their partners’ conflictual behavior. Contrasts of coefficients showed stronger associations between the male holding back x female partner conflictual term and men’s (compared to women’s) cortisol slopes preceding, χ2(2) = 8.45, p < .05, and (marginally) during the discussion, χ2(2) = 5.05, p < .10, as well as their cortisol levels after the discussion, χ2(2) = 6.03, p < .05, and their overall response curves, χ2(2) = 7.84, p < .05.

Table 4.

Relations Between Male and Female Partners’ Behaviors and Men’s Cortisol Trajectories

| Model Predictors | Pre-Discussion | Discussion | Post-Discussion | Overall Response | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Cortisol Level | Cortisol Slope | Curvature | ||||||||

| Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | Coeff | p | |

| A. Negative Reciprocity | ||||||||||||||

| F Conflictual | −.037 | .48 | .099 | .25 | .022 | .66 | .033 | .25 | .028 | .56 | −.012 | .83 | −.038 | .39 |

| M Conflictual | .094 | .12 | −.092 | .30 | .046 | .44 | −.016 | .59 | .052 | .36 | .036 | .52 | .043 | .33 |

| F x M Conflictual | .016 | .74 | −.027 | .72 | −.011 | .83 | −.034 | .17 | −.033 | .51 | −.039 | .39 | −.004 | .91 |

| B. Demand-Withdraw | ||||||||||||||

| F Conflictual | .022 | .60 | −.009 | .87 | .023 | .59 | .010 | .69 | .032 | .41 | .023 | .59 | .011 | .71 |

| M Hold Back | −.033 | .51 | .107 | .15 | .024 | .57 | .022 | .43 | .020 | .62 | −.036 | .53 | −.049 | .23 |

| F Conflictual x M Hold Back | .002 | .96 | −.194 | .006 | −.104 | .01 | −.047 | .07 | −.102 | .01 | .052 | .29 | .083 | .02 |

| C. Positive Reciprocity | ||||||||||||||

| F Supportive | −.043 | .41 | −.093 | .20 | −.097 | .03 | −.029 | .17 | −.101 | .02 | .014 | .77 | .036 | .34 |

| M Supportive | .031 | .55 | .079 | .27 | .070 | .19 | .008 | .73 | .061 | .22 | −.039 | .38 | −.040 | .26 |

| F x M Supportive | .020 | .68 | .081 | .17 | .044 | .32 | −.026 | .23 | .007 | .86 | −.098 | .01 | −.061 | .04 |

Note. p < .05 indicated in bold; p < .10 indicated in bold italics.

Figure 3.

Female partner conflictual behavior and male partner holding back interact to predict men’s cortisol.

The final set of models was designed to test the impact of positive behaviors on partners’ stress responses; this showed a main effect of female partners’ supportive behavior on male partners’ cortisol levels during and after the discussion, as well as an interaction of male x female partner supportive behavior predicting men’s post-discussion slopes and their overall response curves (see Table 4, panel C). High partner supportiveness during the discussion appeared to benefit men by lowering their cortisol levels. The interaction results showed a greater benefit of partners’ supportive behavior for men’s cortisol recovery post-discussion if they themselves provided high levels of support. Figure 4 shows expected men’s cortisol trajectories, plotted at high (+1) and low (−1) levels of their own and their partners’ supportive behavior. Contrasts of coefficients showed stronger associations between partner supportive behavior and men’s (compared to women’s) cortisol levels during, χ2(2) = 5.88, p < .05, and following the discussion, χ2(2) = 6.59, p < .05. In addition, men showed stronger associations between the male x female partner supportive term and cortisol slopes after the discussion, χ2(2) = 7.54, p < .05, and (marginally) their overall response curves, χ2(2) = 4.60, p < .10.

Figure 4.

Female and male partner supportive behaviors interact to predict men’s cortisol.

In summary, the above model results2 support gender-specific associations between couples’ behavior patterns involving negative reciprocity, demand-withdraw, and/or low positivity and HPA dysregulation. In particular, whereas high mutual conflictual behavior and female conflictual-male holding back patterns predicted lower cortisol levels but delayed post-discussion recovery for women, low partner supportiveness predicted higher cortisol levels for men. At the same time, examining both sides of cross-partner interactions showed that the impact of a given partner’s behavior should not be interpreted outside the context of the other partner’s behavior. This distinction was especially important for the demand-withdraw dynamic; whereas at high levels of partner holding back, women’s conflictual behavior appeared harmful (i.e., delaying their recovery), at low levels of partner holding back, the opposite was true. Similarly, men’s holding back only appeared helpful (i.e., lowering their cortisol) at high levels of partner conflictual behavior.

4. Discussion

This study extends findings from marital literature that negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw behaviors during discussion of conflict can be harmful, and positive behavior helpful, while further specifying how—via regulation of HPA responses—and defining the role of each partner’s behavior in unmarried couples’ stress physiology. Young women’s conflictual and supportive behaviors and men’s holding back related to partners’ cortisol responses to discussion of unresolved relationship issues. Whereas women’s cortisol was more tightly aligned with the negative behavior patterns, men’s cortisol showed more associations with the positive pattern. In each case, partners’ behaviors interacted to predict their HPA response components in different ways for men vs. women. Demonstrating these associations in the current sample of young dating couples underlines the importance of these behavior dynamics from the very earliest stages of relationship development. Below, we consider how these findings add to a conceptualization of couples’ stress regulation.

Gender differences observed here are in line with previous behavioral research suggesting female partners are more vulnerable to (self) demand-(partner) withdraw dynamics, whereas male partners can actually benefit from strategic withdrawal and are more reliant on partners’ support [9]. These results also converge with previous research showing stronger relations between negative behavior patterns and women’s cortisol—in particular, negative reciprocity associated with lower women’s cortisol during discussion of conflict [31] but less post-discussion recovery [30], or demand-withdraw associated with higher end-of-discussion women’s cortisol [33]. It appears that even among unmarried young couples, women may both suffer more from problematic behavior dynamics and carry more responsibility for their partner’s well-being during discussion of conflict. We were unable to explain these differences through partners’ levels of sociotropy, reassurance seeking, or rejection sensitivity, yet there may be untapped gender role-related differences in relative power and/or investment in harmonious relationships that underlie this asymmetry, as suggested in marital research. In particular, young women may place more value on conflict resolution and feel defeated by a partner who refuses to engage constructively, whereas young men simply appreciate their partner’s support but care less about solving differences within the existing balance of the relationship. For now, we can say that the same sorts of dynamics observed in marital research appear to operate in emerging adult dating relationships.

Whereas some behavior associations applied to cortisol levels and/or change specific to the discussion itself, others applied to levels of HPA activity that were not in reaction to the discussion, consistent with different underlying causal models. Both negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw patterns were associated with lower women’s cortisol not only during the discussion, but also upon entry to the laboratory. It may be that low pre-discussion cortisol makes female partners more likely to reciprocate partner conflictual or holding back behaviors with their own conflictual behavior, or that these characteristics indicate an underlying trait-like disposition giving rise to both HPA hypoactivity and negative behavior patterns. On the other hand, demand-withdraw was associated with discussion-specific reactivity (for men) and lack of recovery (for women), and mutual support with men’s recovery. These relations are more consistent with a causal chain from behavior to HPA activity and suggest that at least some of the well-documented costs and benefits of couples’ behaviors have to do with impacts on conflict-related physiology.

The fact that all behavior-cortisol relations were qualified by interactions confirms that one partner’s behavior should not be interpreted as helpful or harmful without the context of the other partner’s behavior. Although previously identified dyadic patterns capture some part of these associations, they tend to only highlight one constellation (e.g., high male/high female negativity) and offer little guidance for when a given partner’s behavior should matter. In the present study, women’s conflictual behavior only related to problematic cortisol responses when their partner reciprocated with highly conflictual behavior or holding back; at lower levels of these partner behaviors, increases in women’s conflictual behavior actually related to better cortisol regulation. This suggests that conflict is not necessarily a bad thing [39], and that mutual engagement in a discussion of an unresolved relationship issue is more important for women than avoiding conflict altogether. Current results further suggest an adaptive value for men of holding back only when their partner was highly conflictual. Paired with a non-conflictual partner, men’s holding back related to heightened cortisol reactivity, perhaps indicating an anxious disposition and/or a sense of uncontrollable threat rather than a calculated escape. This provides a more precise context for previous assertions that men are reinforced for withdrawal from discussion of conflict [19] and underlines the differing male vs. female partner motivations that may cause demand-withdraw dynamics to become entrenched. Given these differing risk/protective factors, the goal should be for both partners to work on resolving conflict without becoming overly negative or polarized in their roles.

Gender differences were also evident in the components of HPA response related to couples’ behaviors, highlighting the need for modeling approaches that can distinguish these components and background work relating these to adjustment. Whereas more negative behavior patterns related to lower women’s cortisol, less positive patterns related to higher men’s cortisol, and both related to flattened post-discussion recovery slopes. This underlines the value of examining both cortisol levels and temporal dynamics to distinguish between couples’ experiences; although both high and low levels of negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw related to low women’s cortisol, only the former (presumably more harmful) pattern related to delayed recovery. Previous work in this sample relating cortisol trajectories to depressive symptoms was necessary to fully interpret these associations. Knowing that hyporesponse/delayed recovery vs. hyperresponse were indicative of emotional dysregulation for female vs. male partners offered insight into the (mal)adaptive value of each pattern [29]. That is, negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw related to female-typical HPA dysregulation, and support related to male-typical HPA regulation. In addition, we found previously that men’s holding back and women’s conflictual behavior each related to elevated depressive symptoms [40]. Together, these links provide a basis for proposing gender-specific paths from behaviors during discussion of conflict to depression via HPA dysregulation. While a full test of this model lies beyond the scope of the present study, the current findings add an important piece to the couples behavior-health puzzle and suggest further investigation of mediating models involving partners’ physiology is warranted.

Beyond illuminating couples’ conflict-physiology associations, these results provide information that could be useful in couples intervention. Behavior correlates similar to those found in marital couples confirm that constructive or destructive patterns develop and begin exerting an impact on physiology quite early in the development of romantic relationships, and that intervention in risky non-marital couples may be justified. Specifically, early identification of couples who rely on negative reciprocity or demand-withdraw patterns and efforts to increase supportive conflict resolution could head off long-term biobehavioral dysregulation that partners would carry into future relationships, including marriage. Video feedback interventions could be used with distressed couples to point to harmful dynamics and, perhaps more importantly, to places where partners worked well together. Knowing that particular behaviors—i.e., conflictual—carry a greater cost when used to counter the partner’s highly conflictual or withdrawing behavior, whereas others—i.e., supportive—carry a greater benefit when used by both partners could help to reinforce behavioral prescriptions for both members of the couple. At the same time, the cross-partner interactions shown here indicate that just one partner’s changing his/her behavior could make a substantial difference in the impact of the other’s behaviors. Thus, while interventions involving both partners are ideal given the synergy of partners’ behaviors, individual-level intervention should not be discounted in cases of relationship-related distress.

Limitations of the current study suggest future directions for research. As described above, multiple causal paths may operate between couples’ behaviors and HPA, and this should be further explored with more controlled studies of baseline cortisol effects on behavior, behavioral effects on cortisol change, and third variables potentially underlying behavior-cortisol associations. Although the behavior codes used here were comparable in specificity and content to those used in other couples stress research, more nuanced coding of the affective and behavioral qualities associated with each could offer greater insight into couples processes. In particular, the possibility that some of the gender differences in behavior associations had to do with differences in what young men vs. women considered “conflictual” should be further explored. Observer coding of interactions could also be used to investigate whether discrepancies between self-perceived and externally rated behaviors matter for physiological stress, providing further guidance for intervention.

The sample of unmarried couples used in this study helped to extend research based predominantly on married couples, but a more in-depth examination of potential changes in the importance of particular behaviors across the transition to marriage requires longitudinal study of unmarried and married couples. This could tell us more about which conflict discussion profiles are likely to have long-term negative consequences for HPA regulation and related health outcomes, and which are likely to fade with time. Based on the couples development literature, we might hypothesize that the behavior-cortisol associations found here would become weaker or stronger in longer-term relationships; on the one hand, greater familiarity with the partner and relationship might lessen the impact of a given behavioral exchange, but on the other hand, repeated positive or negative interactions could have a greater cumulative effect over time. Each of these possibilities should be further explored in developmental research. Finally, as mentioned above, the combined implications of this study and previous work in this sample point to cortisol as a possible mediator in couples’ conflict-mental health associations; this should be further explored, and cortisol responses to discussion of conflict compared with responses to other naturalistic and standardized stressors to determine which stress mechanisms are most important to target in interventions.

In sum, this study adds to an understanding of how daily interpersonal stress translates into physiology by demonstrating gender-specific links between romantic partners’ behaviors during discussion of conflict and their HPA responses. A tendency for female partners to show a tighter alignment between stress responses and harmful behaviors in romantic relationships may help to understand women’s increased susceptibility to depression and other stress-related disorders and inform points of intervention.

Highlights.

We investigated relations between romantic partners’ conflict behaviors and HPA responses

Male and female partner behaviors interacted to predict HPA

Negative reciprocity and demand-withdraw slowed women’s post-stress recovery

Mutual supportive behavior buffered men’s stress response

Impacts of a partner’s conflict behavior depend on the other partner’s behavior

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health R01 MH60228-01A1.

Footnotes

A single-item “engagement” rating (1–5 scale) assigned by outside coders to discussion videos was positively related to male partner, female partner, and male x female partner conflictual behavior scores. It also related negatively to male holding back x female partner conflictual behavior but was unrelated to each partner’s holding back and supportive behavior scores. Finally, engagement related to higher cortisol levels during the discussion for both male (b = .09, p = .04) and female partners (b = .13, p = .002), but especially for the latter, χ2(2) = 12.93, p < .01. to men’s) cortisol levels preceding, χ2(2) = 6.03, p < .05, and during the discussion, χ2(2) = 7.66, p < .05, as well as their slopes after the discussion, χ2(2) = 7.12, p < .05.

Follow-up models were run to rule out potential confounds in reported results. First, because male partner holding back and conflictual behavior were positively associated, models were also run controlling for the other behavior. Second, given proposals that gender differences in behavior associations have to do with differences in power and/or interpersonal sensitivity, separate models controlling for indices of partners’ vulnerability to relationship disharmony—sociotropy, rejection sensitivity, and reassurance seeking—were run. Including these variables failed to significantly alter reported models (i.e., new coefficients were within the 98% confidence interval of the original), suggesting results were indeed unique to those behaviors. This was also true in models with individual partners (rather than couples) as the unit of analysis, and with gender interaction terms tapping into differential behavior associations for men vs. women.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Heidemarie K. Laurent, University of Wyoming

Sally I. Powers, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Holly Laws, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Meredith Gunlicks-Stoessel, University of Minnesota Medical School

Eileen Bent, John D. Dingell VA Medical Center

Susan Balaban, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

References

- 1.Cacioppo JT. Somatic responses to psychological stress: The reactivity hypothesis. In: Sabourin M, Craik F, Robert M, editors. Advances in psychological science, vol. 2: Biological and cognitive aspects. Hove, England: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis MC, Burleson MH, Kruszewski DM. Gender: its relationship to stressor exposure, cognitive appraisal/coping processes, stress responses, and health outcomes. In: Contrada RJ, Baum A, editors. The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunkel Schetter C, Dolbier C. Resilience in the context of chronic stress and health in adults. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2011;5:634–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith T, Birmingham W, Uchino BN. Evaluative threat and ambulatory blood pressure: Cardiovascular effects of social stress in daily experience. Health Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0026947. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiol Beh. 2003;79:409–16. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitson S, El-Sheikh M. Marital conflict and health: Processes and protective factors. Aggress Violent Beh. 2003;8:283–312. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitton SW, Olmos-Gallo PA, Stanley SM, Prado LM, Kline GH, St Peters M, et al. Depressive symptoms in early marriage: Predictions from relationship confidence and negative marital interaction. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, et al. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent HK, Kim HK, Capaldi DM. Interaction and relationship development in stable young couples: Effects of positive engagement, psychological aggression, and withdrawal. J Adol. 2008;31:815–35. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurent HK, Kim HK, Capaldi DM. Longitudinal effects of conflict behaviors on depressive symptoms in young couples. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23:596–605. doi: 10.1037/a0015893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panuzio J, DiLillo D. Physical, psychological, and sexual intimate partner aggression among newlywed couples: Longitudinal prediction of marital satisfaction. J Fam Violence. 2010;25:689–99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taft CT, O’Farrell TJ, Torres SE, Panuzio J, Monson CM, Murphy M, et al. Examining the correlates of psychological aggression among a community sample of couples. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:581–88. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodin EM. A two-dimensional approach to relationship conflict: Meta-analytic findings. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25:325–35. doi: 10.1037/a0023791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldridge KA, Christensen A. Demand-withdraw communication during couple conflict: A review and analysis. In: Noller P, Feeney JA, editors. Understanding marriage: Developments in the study of couple interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGinn MM, McFarland PT, Christensen A. Antecedents and consequences of demand/withdraw. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23:749–57. doi: 10.1037/a0016185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papp LM, Kouros CD, Cummings ME. Demand-withdraw patterns in marital conflict in the home. Pers Relat. 2009;16:285–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen A, Eldridge K, Catta-Preta AB, Lim VR, Santagata R. Cross-cultural consistency of the demand/withdraw interaction pattern in couples. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68:1029–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen A, Heavey CL. Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:73–81. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verhofstadt LL, Buysse A, De Clercq A, Goodwin R. Emotional arousal and negative affect in marital conflict: The influence of gender, conflict structure and demand-withdrawal. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2005;35:449–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holley SR, Sturm VE, Levenson RW. Exploring the basis for gender differences in the demand-withdraw pattern. J Homosex. 2010;57:666–84. doi: 10.1080/00918361003712145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ströhle A, Holsboer F. Stress responsive neurohormones in depression and anxiety. Pharmacopsych. 2003;36:S207–14. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handwerger K. Differential patterns of HPA activity and reactivity in adult posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17:184–205. doi: 10.1080/10673220902996775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cagampang FR, Poore KR, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: Body clocks and stress responses. Brain Beh Immun. 2011;25:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:959–97. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morale C, Brouwer J, Testa N, Tirolo C, Barden N, Dijkstra CD, Amor S, Marchetti B. Stress, glucocorticoids and the susceptibility to develop autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:159–62. doi: 10.1007/s100720170016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:846–56. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurent HK, Ablow JC, Measelle J. Risky shifts: How the timing and course of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the perinatal period shape their own and infant’s stress response profiles. Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23:521–38. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers SI, Gunlicks M, Laurent H, Balaban S, Bent E, Sayer A. Differential effects of subtypes of trauma symptoms on couples’ hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity and recovery in response to interpersonal stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:430–33. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers SI, Laurent HK, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Balaban S, Bent E. Depression and anxiety predict cortisol responses to romantic relationship conflict. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.007. under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Cacioppo JT, MacCallum RC, Snydersmith M, Kim C, et al. Marital conflict in older adults: Endocrinological and immunological correlates. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:339–49. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fehm-Wolfsdorf G, Groth T, Kaiser A, Hahlweg K. Cortisol responses to marital conflict depend on marital interaction quality. Int J Behav Med. 1999;6:207–27. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0603_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robles TF, Schaffer VA, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Positive behaviors during marital conflict: Influences on stress hormones. J Soc Pers Relat. 2006;23:305–25. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heffner KL, Loving TJ, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Himawan LK, Glaser R, Malarkey WB. Older spouses’ cortisol responses to marital conflict: Associations with demand/withdraw communication patterns. J Behav Med. 2006;29:317–25. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham JD, Braiker H, Kelley HH. Marital-status and sex differences in problems reported by married and cohabiting couples. Psychol Women Q. 1982;6:415–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florsheim P, Moore D, Edgington C. Romantic relations among adolescent parents. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson RW, Clore GL, Wood GA. The emotions of romantic relationships: Do they wreak havoc on adolescents? In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welsh DP, Galliher RV, Kawaguchi MC, Rostosky SS. Discrepancies in adolescent romantic couples’ and observers’ perceptions of couple interaction and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:645–666. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powers SI, Welsh DP, Wright V. Adolescents’ affective experience of family behaviors: The role of subjective understanding. J Res Adol. 1994;4:585–600. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powers SI, Battle CL, Dorta K, Welsh DP. Adolescents’ submission and conflict behaviors with mothers predicts current and future internalizing problems. Res Hum Dev. 2010;7:257–73. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powers SI, Laws HR, Laurent HK, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Balaban S, Bent E, et al. Modeling Psychosocial Risks for Depression in Couples: When Does Gender Matter?. International Association of Relationship Research, Regional Conference on Health, Emotion, and Relationships; Tucson, Arizona. 2011. [Google Scholar]