Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes strains can be divided into two classes, one capable and the other incapable of producing H2O2 (M. Saito, S. Ohga, M. Endoh, H. Nakayama, Y. Mizunoe, T. Hara, and S. Yoshida, Microbiology 147:2469-2477, 2001). In the present study, this dichotomy was shown to parallel the presence or absence of H2O2-producing lactate oxidase activity in permeabilized cells. Both lactate oxidase activity and H2O2 production under aerobic conditions were detectable only after glucose in the medium was exhausted. Thus, the glucose-repressible lactate oxidase is likely responsible for H2O2 production in S. pyogenes. Of the other two potential H2O2-producing enzymes of this bacterium, NADH and α-glycerophosphate oxidase, only the former exhibited low but significant activity in either class of strains. This activity was independent of the growth phase, suggesting that the protein may serve in vivo as a subunit of the H2O2-scavenging enzyme NAD(P)H-linked alkylhydroperoxide reductase. The activity of lactate oxidase was associated with the membrane while that of NADH oxidase was in the soluble fraction, findings consistent with their respective physiological roles, i.e., the production and scavenging of H2O2. Analyses of fermentation end products revealed that the concentration of lactate initially increased with time and decreased on glucose exhaustion, while that of acetate increased during the culture. These results suggest that the lactate oxidase activity of H2O2-producing cells oxidizes lactate to pyruvate, which is in turn converted to acetate. This latter process proceeds presumably via acetyl coenzyme A and acetyl phosphate with formation of extra ATP.

The gram-positive microorganism Streptococcus pyogenes is the causative agent of a variety of important human diseases. These include not only the direct consequences of infections such as pharyngitis, impetigo, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and toxic-shock-like syndrome but also secondary pathologies called poststreptococcal sequelae. The physiological features of S. pyogenes place it as a member of lactic acid bacteria, which are generally believed to be almost totally dependent for growth on the lactic mode of fermentation under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

In a number of species of lactic acid bacteria, it has been known that cells growing aerobically produce and excrete copious amounts of H2O2. In a previous study, it was found that S. pyogenes strains could be divided into two classes with respect to the production of H2O2, i.e., producers and nonproducers (18). However, the metabolic basis and biological significance of bacterial H2O2 production are largely unexplored. The presence of H2O2-producing oxidases in lactic acid bacteria has been demonstrated, and the possibility of their involvement in this phenomenon has been suggested (6, 14, 15, 21). Notably, a homology search against the S. pyogenes genome database revealed that putative H2O2-producing oxidases for NADH, lactate, and α-glycerophosphate are present but not that for pyruvate (6). Evidence for their actual contribution to H2O2 production is lacking.

In the present study, we examined cells of H2O2-producing and -nonproducing S. pyogenes strains for the activities of the above-mentioned oxidases. Our results clearly demonstrated that lactate oxidase was almost exclusively responsible for H2O2 production in S. pyogenes. Furthermore, we showed that lactate oxidation, which took place when the cells ran out of glucose, was accompanied by the formation of acetate as an end product. This strongly suggests that the thioclastic pathway (see reference 20) is operating, which enables the cells to obtain ATP in the absence of glucose.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

S. pyogenes strains used in this study consisted of five H2O2 producers (MK5, SP2, ME1410, ME1123, and ME1559) and five H2O2-nonproducing varieties (ME157, SP1, ME206, ME1125, and ME198). Strains ME157 and ME1559 were obtained from M. Endo (Tokyo Metropolitan Research Laboratory of Public Health); the rest were described previously (17, 18). Tryptone-yeast (TY) medium (pH 7.4) contained 1% tryptose (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), 0.2% yeast extract (Difco), and 0.5% NaCl. Unless otherwise stated, cultures were grown overnight in this medium at 37°C with shaking, diluted 1:100 in the same fresh medium supplemented with 0.1% glucose (TYG medium), and further shaken at 37°C until used. This method of culture is referred to as the standard conditions. Cell harvest was achieved by centrifugation at 2,380 × g for 10 min. Catalase (200 U/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and 0.1% sodium lactate were added to culture medium when appropriate.

Spectrophotometric measurement.

A Spectronic Genesys 5 spectrophotometer (Milton Roy Co., Rochester, N.Y.) was used for all photometric assays including turbidometry of cultures. The light path was 1 cm in length.

Assay of glucose concentration.

The assay was carried out with the Wako Glu2 kit (L-type; Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Determination of H2O2 in culture supernatant.

As previously described (9), a 5-μl sample of culture medium was added to 0.75 ml of a solution containing 0.51 mM 4-aminoantipyrine (4-amino-2,3-dimethyl-1-phenyl-3-pyrazolin-5-one; Sigma), 10.6 mM phenol, and horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) at a concentration of 0.71 mU/ml, in 30 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 20 min at 37°C. The A505 of each reaction was converted to H2O2 concentration with a standard curve generated by authentic H2O2.

Assay of H2O2-producing oxidase activities.

The assay was carried out by H2O2 determination. In the case of NADH oxidase, lactate oxidase, and α-glycerophosphate oxidase, the reaction mixture consisted of 30 μl of enzyme and 0.6 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 13 mM NADH (Sigma), 8.9 mM sodium lactate (Sigma), and 30 mM α-glycerophosphate (Wako), respectively. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the enzyme and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 60 μl of 1 N HCl, the mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g, and a 0.5-ml portion of the supernatant was neutralized with 60 μl of 1 N NaOH. Following the addition of 15 μl of a solution containing 67 mM 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothioazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma) and 10 U of horseradish peroxidase (Wako) to the neutralized supernatant, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 min, and the A414 was measured. Unless specified otherwise, permeabilized cells prepared in the following manner were used as the enzyme: cells in culture samples were collected, resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to give an optical density (turbidity) at 600 nm (OD600) of 3, and treated with 20 μl of toluene added to each milliliter of the suspension by gentle agitation for 1 min. In the case of pyruvate oxidase, a modification of a method previously described (10) was used with permeabilized cells serving as the enzyme. The reaction mixture consisted of 30 μl of enzyme and 0.6 ml of a solution containing 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 10 μM MgCl2, 0.2 μM thiamine pyrophosphate (Sigma), 50 μM potassium pyruvate, and 12 μM flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD; Sigma). The reaction was initiated by the addition of the enzyme and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 1 min at 16,000 × g, and a 0.5-ml portion of the supernatant was subjected to H2O2 determination as described above.

Estimation of H2O2-decomposing capacity.

Stationary-phase cells grown in TYG medium under the standard conditions and permeabilized as described above were used as the enzyme. The reaction mixture consisted of 30 μl of the enzyme and 0.6 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 13 mM NADH and 5 mM H2O2. To avoid interference by H2O2 formation by intrinsic oxidases, the buffer had been deoxygenated by boiling, and the reaction was performed under liquid paraffin. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the enzyme, incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and terminated by adding 60 μl of 1 N HCl. After the removal of the cells by centrifugation for 5 min at 16,000 × g, the remaining H2O2 was estimated by mixing a 60-μl portion of the supernatant into 0.6 ml of a 5% titanium sulfate reagent for H2O2 determination (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) followed by reading the A420.

Preparation of subcellular fractions.

Cells actively producing H2O2 were harvested and resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at an OD600 of 6. A 5-ml portion of the suspension was treated with toluene as described above to permeabilize the cells. Another 5-ml portion was treated with achromopeptidase (100 U/ml; Wako) at 37°C for 1 h followed by ultrasonic irradiation 10 times with glass beads at 100 W for 1 min on ice in a sonicator (SONIFIER 250; Branson, Danbury, Conn.). The sonicate, containing only a few morphologically intact cells as judged by Gram staining and electron microscopy, was freed from such cells by spinning at 1,750 × g for 10 min and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was saved as the soluble fraction while the pellet, after being washed once with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) by centrifugation, was resuspended in the original volume of the same buffer to give the membrane fraction.

Analysis of fermentation products.

The concentration of l-lactate in the culture supernatant was determined with the use of l-lactate dehydrogenase (from rabbit muscle) (Sigma) as described by Hohorst (12). Other fermentation products were quantitated by gas liquid chromatography. Formate and acetate were analyzed as methyl esters by the method previously described (13) with some modifications. Thus, 0.5 ml of a culture supernatant was pipetted into a headspace glass vial (approximately 10-ml capacity), to which 0.3 ml of sulfuric acid (Wako) was slowly added. After thorough mixing, the vial was cooled in an ice-water bath and received 0.05 ml of methanol and 0.5 ml of a solution containing 500 μg of acetonitrile, which served as an internal reference. The vial was immediately sealed with an aluminum cap with a silicone-lined rubber septum and incubated for 10 min at 60°C. The headspace gas (1.0 ml) was injected through a headspace sampler (model HP7694; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, Calif.) into a gas chromatograph (model 5890 series II; Hewlett-Packard) equipped with a hydrogen flame ionization detector. Chromatographic separation was effected on a DB-WAS gas chromatography column (length, 30 m; inside diameter, 0.53 mm; film thickness, 1.0 μm) (J & W Scientific, Folsom, Calif.). The carrier gas used was helium with a flow rate of 20 ml/min. The injector and detector temperatures were 250°C. For analysis of ethanol, the same procedure was used except that sulfuric acid and methanol were omitted. A series of solutions containing various amounts of the authentic substances were analyzed in the same way to yield calibration curves, from which the concentrations of formic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol in the sample were determined.

Pyruvate cleavage reaction.

A modification of a method previously described (22) was used with permeabilized cells serving as the enzyme. The complete reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 ml of enzyme and 0.9 ml of a solution containing 67 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2.2 mM CaCl2, 14 mM coenzyme A (Sigma), 0.83 mM 3-acetylpyridine NAD+ (Sigma), 0.44 mM thiamine pyrophosphate (Sigma), 2.9 mM dithiothreitol, and 5.6 mM sodium pyruvate. EDTA was added at a final concentration of 2 mM when appropriate. The reaction at 30°C was started by adding enzyme, and the change in A340 was followed.

RESULTS

Time course of H2O2 production.

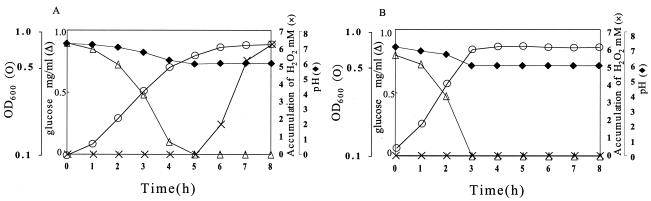

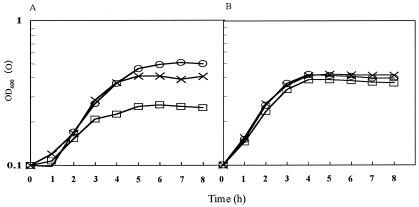

Previous work has demonstrated that H2O2 production by S. pyogenes cells is repressed by a high concentration of glucose in the medium (6, 18) and could be seen only in a later phase of culture (18). This fact suggested that the exhaustion of glucose in the culture medium was required for the production of H2O2. When the concentration of glucose and H2O2 was monitored in a culture of strain MK5 grown in TYG medium, H2O2 became detectable immediately after the glucose was exhausted (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no H2O2 was detected in a culture of the H2O2-nonproducing strain ME157 even after the glucose had been consumed completely (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Time course of H2O2 production and glucose consumption in relation to bacterial growth. Strain MK5, an H2O2 producer (A), and strain ME157, an H2O2 nonproducer (B), were cultured in TYG medium at 37°C with shaking. Symbols: ○, turbidity (OD600); ▵, glucose; ×, H2O2; ♦, pH. Representative data from 10 independent experiments are shown.

Activities of H2O2-producing oxidases.

In view of the documented possibility that the production of H2O2 in lactic acid bacteria is mediated by H2O2-producing oxidases (6, 14, 15, 21), we studied the activities of such enzymes in S. pyogenes cells. Three oxidases may be considered on the basis of an enzymatic study (23) and a search against the S. pyogenes genome database (6), i.e., the oxidases for NADH, lactate, and α-glycerophosphate. Pyruvate oxidase, another possible candidate, has been shown to be absent in this organism (6, 23). We confirmed these database search results and went on to carry out assays for these oxidase activities by using permeabilized cells as an enzyme preparation.

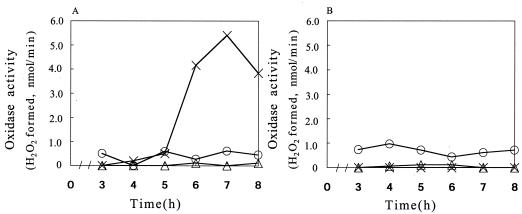

In strain MK5, the activity of lactate oxidase started increasing steeply at 5 h of cultivation under the standard conditions (Fig. 2A), when glucose became undetectable and the level of H2O2 was about to rise (Fig. 1A). A low but significant level of NADH oxidase activity was seen throughout the cultivation period, while that of α-glycerophosphate oxidase was undetectable (Fig. 2A). In strain ME157, by contrast, neither lactate oxidase nor α-glycerophosphate oxidase activity was detected, whereas the level of NADH oxidase activity was similar to that in MK5 (Fig. 2B). We also examined the other eight strains for lactate oxidase activity and found that it was produced in all of the H2O2 producers but none of the nonproducers. Thus, the presence or absence of H2O2 production correlated with demonstrable lactate oxidase activity. In addition, we confirmed that pyruvate oxidase activity was absent from all of the strains used. From these results, it seemed highly likely that the lactate oxidase activity, which appeared upon glucose exhaustion, was mainly responsible for the H2O2 production. This glucose effect seemed not to be due to an inhibition of the enzyme activity: once cells started producing H2O2, they continued to do so even when harvested and resuspended in glucose-supplemented medium (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Growth-phase-dependent changes in the activity of H2O2-producing oxidases. Cultures of strain MK5 (A) and strain ME157 (B) were grown in TYG medium at 37°C with shaking, and samples taken at intervals were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.3. The cells in 5-ml portions were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.5 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, and permeabilized by treatment with 10 μl of toluene. The activities were measured with 30 μl of the cell suspension under the conditions described in Materials and Methods and expressed as micromoles of H2O2 formed per minute. Symbols: ○, NADH oxidase; ▵, α-glycerophosphate oxidase; ×, lactate oxidase.

In theory, the H2O2-producing phenotype might possibly result from a diminished capacity of the cell to scavenge endogenous H2O2. To test this possibility, we examined permeabilized cells of strains MK5 and ME157 for the ability to decompose H2O2. NADH was added to the reaction because both alkylhydroperoxide reductase (NCBI AAK34732 and AAK34733) and NADH peroxidase (NCBI AAK34437), likely scavengers for H2O2 in this organism, require it as a reductant. The results obtained did not support the above possibility: the H2O2-decomposing activity of H2O2-producing cells was indistinguishable (without NADH) from, or even higher (with NADH) than, that of H2O2-nonproducing cells (data not shown).

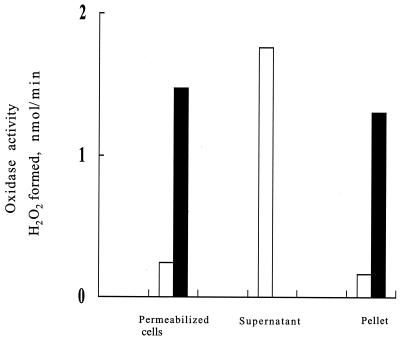

Subcellular localization of lactate and NADH oxidases.

The subcellular localization of lactate and NADH oxidases in permeabilized cells of strain MK5 were studied by disrupting cells by achromopeptidase-mediated digestion of the cell wall followed by sonication. Whereas NADH oxidase activity was mainly present in the soluble fraction of the sonicate, lactate oxidase was detected only in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 3). These results strongly suggest that in S. pyogenes NADH oxidase is a cytoplasmic enzyme, while lactate oxidase is somehow associated with the membrane. Incidentally, it was noted that the enzyme activities exhibited by permeabilized cells represented approximately 14% of those shown by the sonicate.

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of H2O2-producing oxidases. Cells of strain MK5 grown in TYG medium under the standard conditions for 5 h (see legend to Fig. 1) at 37°C with shaking were harvested and processed as described in Materials and Methods. The supernatant and the pellet denote the soluble and membrane fractions, respectively. The lactate oxidase activity was not detected in the supernatant. The enzyme activity shown represents the total activity contained in each 5-ml preparation (see Materials and Methods). Open bars, NADH oxidase activity; filled bars, lactate oxidase activity.

Analysis of fermentation products.

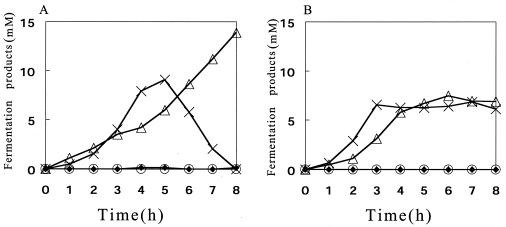

Since the H2O2 production was likely to be mediated by the lactate oxidase activity, it was necessary to look at possible changes in the profile of fermentation products in relation to H2O2 production. In strain MK5 cultured under the standard conditions, the concentration of lactate increased for 5 h, then started to decline, and became undetectable after 8 h; the concentration of acetate, on the other hand, increased with time throughout the culture period (Fig. 4A). In strain ME157, by contrast, the concentration of lactate and acetate reached a plateau at 3 and 6 h of culture, respectively, and no decrease in the level of lactate was observed (Fig. 4B). Neither formate nor ethanol was detected in the culture of either strain.

FIG. 4.

Growth-phase-dependent changes in the concentration of fermentation products in the culture medium. Cells of strain MK5 (A) and strain ME157 (B) were cultured in TYG medium under the standard conditions, and analyses of the products were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: ○, ethanol; ▵, acetate; ×, l-lactate, ♦, formate.

Cell yield studies.

The most plausible explanation for the findings described above is that, after glucose exhaustion, lactate oxidase converted lactate to pyruvate, the latter being further metabolized to acetate via acetyl coenzyme A. Since acetate formation through this pathway is known to be coupled with ATP generation, this interpretation predicts an increase in the final cell yield to accompany the lactate consumption. This was actually the case (Fig. 5). Stationary-phase cells of strains MK5 and ME157 grown under the standard conditions in the presence of catalase, which was included to prevent the cytotoxic effect of the H2O2 produced, were harvested, washed, and resuspended in TY medium with or without lactate and catalase. In the presence of catalase, the lactate-supplemented culture of the H2O2 producer clearly attained a slightly higher cell density than that without lactate (OD600 of 0.5 versus 0.4) (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, lactate did not affect the cell yield of the H2O2 nonproducer in the presence or absence of catalase (Fig. 5B). The absence of catalase from the lactate-supplemented culture of the H2O2 producer resulted in a decreased cell yield, probably due to the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 (Fig. 5A). We also examined the other eight strains to find that the lactate-mediated increase in the cell yield was seen in all of the H2O2 producers but none of the nonproducers.

FIG. 5.

Effect of added lactate on cell yield. The H2O2-producing strain MK5(A) and the nonproducing strain ME157(B) were cultured in TYG medium at 37°C with shaking in the presence of catalase. Stationary-phase cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in fresh TY medium supplemented with or without 0.1% sodium lactate and catalase (200 U/ml). Symbols: ○, with lactate and catalase; ×, with catalase only; □, with lactate only.

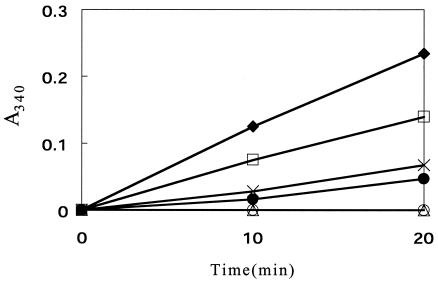

Demonstration of pyruvate cleavage reaction.

It is known that streptococci, like many other bacteria, produce formate, acetate, and ethanol by the involvement of pyruvate formate-lyase under anaerobic conditions (1). However, this enzyme is generally believed to be inactive under aerobiosis. Furthermore, the absence of the production of formate (described above) seemed to rule out the possibility for this enzyme to be involved in the formation of acetate in S. pyogenes under the experimental conditions used here. It has also been documented that H2O2-producing pyruvate oxidase, which converts pyruvate to acetyl phosphate and CO2, is missing in this organism (6, 23). Obviously, an alternative way to cleave pyruvate to give acetyl coenzyme A or acetyl phosphate and a one-carbon compound must operate. Since the most likely candidate for this should be oxidative decarboxylation mediated by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, we examined permeabilized cells of strain MK5 for their ability to carry out pyruvate-dependent reduction of NAD+. 3-Acetylpyridine NAD+ was used instead of NAD+ to avoid possible complication caused by NADH oxidase (22). The results obtained demonstrated that the cells actually possessed such activity, which was EDTA inhibitable and dependent on added thiamine pyrophosphate as well as coenzyme A (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Demonstration of NAD+-linked pyruvate cleavage reaction. Permeabilized cells of strain MK5 were used as the enzyme, and the reduction of acetylpyridine NAD+ was monitored by measuring the A340. Without the enzyme, this reduction was not observed. Symbols: ♦, complete system; ○, less substrate; •, less thiamine PPi; ×, less coenzyme A; □, less Ca2+; ▵, less Ca2+ but plus 2 mM EDTA.

DISCUSSION

Overall, we consider our findings to be consistent with the following general picture. First, lactate oxidase activity is responsible for H2O2 production in S. pyogenes. Second, this activity develops when the glucose supply is consumed, suggesting that catabolite repression-like regulation is operating. Third, in accordance with this type of control, the lactate oxidase activity makes possible the utilization of lactate, which leads to additional acetate formation via acetyl phosphate with a concomitant gain of ATP. Of particular interest is the demonstration that lactate can be utilized as an energy source through an aerobic but nonrespiratory mode of metabolism. A similar situation has previously been surmised in Streptococcus iniae (5).

To understand the underlying mechanisms with regard to the first two points, characterization of the lactate oxidase gene is mandatory. In this connection, our ongoing work has provided preliminary evidence that the lactate oxidase gene is inactive in H2O2-nonproducing strains due to a mutation in the promoter region and has a putative binding site for the catabolite control protein (our unpublished results).

Concerning the last point, the mechanism of pyruvate cleavage must be clarified. Conceptually, there are four different possibilities for this step: the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate oxidase and three so-called thioclastic reactions catalyzed, respectively, by pyruvate formate-lyase, the NAD+-linked pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and ferredoxin-linked pyruvate dehydrogenase. Apart from the ferredoxin-linked reaction that is characteristic of clostridia, our findings indicate that the NAD+-linked enzyme rather than pyruvate formate-lyase is responsible for the cleavage reaction. In agreement with this notion, genes encoding a putative acetoin-pyruvate dehydrogenase complex exist in the genome of S. pyogenes (NCBI AAK33920 to -33923).

If the postglucose, lactate-dependent growth of this bacterium actually occurs as envisaged above, the NADH formed by the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction must be somehow oxidized back into NAD+ to achieve redox balance. This should be possible, at least in theory, if one assumes that half of the pyruvate derived from lactate is channeled into the NADH-forming thioclastic pathway to yield ATP and acetate, while the other half is used to oxidize the NADH by lactate dehydrogenase. In this connection, mention should also be made concerning the formation of acetate that is independent of lactate oxidase activity and evident before glucose exhaustion (Fig. 4). From the above discussion, it would be reasonable to assume that part of the pyruvate derived from glucose is also processed by the NADH-forming thioclastic reaction to put out acetate. Presumably, the participation of NADP+-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NCBI AAM79652), known to be present in this organism in addition to the ordinary NAD+-linked enzyme, is essential for the redox balance to be attained in this situation.

The subcellular localization of H2O2-producing enzymes is of interest because H2O2 is highly cytotoxic. We find that the activity of lactate oxidase of S. pyogenes is associated with the membrane fraction while the NADH oxidase activity is not. Sequencing the putative lactate oxidase gene from strain MK5 has revealed that its product has no hydrophobic region compatible with transmembrane structure (our unpublished observation). This finding suggests that the enzyme represents a peripheral membrane protein, probably associated with the inner surface of the cell membrane. In this connection, it is interesting that the Escherichia coli Lld protein, which is a respiratory chain-linked l-lactate dehydrogenase and apparently paralogous to S. pyogenes lactate oxidase (31% identical in amino acid sequence), is also a protein which is localized on the surface of the cell membrane (4). This subcellular localization is also notable from the physiological point of view. Thus, since H2O2 is known to permeate fairly easily through biological membranes (2), the membrane association of the main producer of H2O2 likely enables the cells to shed H2O2 as it is formed, thereby minimizing damage to their essential components. On the other hand, the cytoplasmic localization of H2O2-producing NADH oxidase seems also reasonable because, as originally noticed by Poole et al. (16) in Streptococcus mutans, this enzyme is a homologue of the AhpF protein of Enterobacteriaceae, a subunit of alkylhydroperoxide reductase. In fact, we have confirmed that S. pyogenes NADH oxidase is 51% identical to E. coli AhpF in amino acid sequence. Since the primary in vivo function of Ahp is to degrade peroxides including H2O2 with NADH or NADPH serving as a reductant (19), it is not at all surprising that the protein is a cytoplasmic enzyme.

Is H2O2 produced by lactate oxidase simply an undesirable by-product of ATP synthesis? In vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that H2O2 produced by S. pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae may act as a potential virulence factor by exerting direct damage to host tissues (3, 7, 8, 11). On the other hand, it has also been shown that in a mouse model of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, the course of the disease was not affected by the ability of infecting S. pyogenes cells to produce H2O2 (17). Furthermore, S. pyogenes isolates derived from a variety of human infections may or may not be H2O2 producers (18). What role the H2O2-producing ability of S. pyogenes plays in infection, therefore, remains an enigma.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to Keiko Kudo (Department of Forensic Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) for her help in gas chromatography and to Hideko Kajiwara (Department of Bacteriology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University) for her technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbe, K., J. Carlsson, S. Takahashi-Abbe, and T. Yamada. 1991. Oxygen and the sugar metabolism in oral streptococci. Proc. Finn. Dent. Soc. 87:477-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chance, B., H. Sies, and A. Boveris. 1979. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 59:527-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duane, P. G., J. B. Rubins, H. R. Weisel, and E. N. Janoff. 1993. Identification of hydrogen peroxide as a Streptococcus pneumoniae toxin for rat alveolar epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 61:4392-4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futai, M., and H. Kimura. 1977. Inducible membrane-bound l-lactate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 252:5820-5827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibello, A., M. D. Collins, L. Dominguez, J. F. Fernandez-Garayzabal, and P. T. Richardson. 1999. Cloning and analysis of the l-lactate utilization genes from Streptococcus iniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4346-4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson, C. M., T. C. Mallett, A. Claiborne, and M. G. Caparon. 2000. Contribution of NADH oxidase to aerobic metabolism of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 182:448-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsburg, I., and M. Sadovnic. 1998. Gamma globulin, Evan's blue, aprotinin A PLA2 inhibitor, tetracycline and antioxidants protect epithelial cells against damage induced by synergism among streptococcal hemolysins, oxidants and proteinases: relation to the prevention of post-streptococcal sequelae and septic shock. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 22:247-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginsburg, I., and J. Varani. 1993. Interaction of viable group A streptococci and hydrogen peroxide in killing of vascular endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14:495-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopalan, K. V., and D. K. Srivastava. 1997. Inhibition of acyl-CoA oxidase by phenol and its implication in measurement of the enzyme activity via the peroxidase-coupled assay system. Anal. Biochem. 250:44-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hager, L. P., D. M. Geller, and F. Lipmann. 1954. Flavoprotein-catalyzed pyruvate oxidation in Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Fed. Proc. 13:734-738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirst, R. A., K. S. Sikand, A. Rutman, T. J. Mitchell, P. W. Andrew, and C. O'Callaghan. 2000. Relative roles of pneumolysin and hydrogen peroxide from Streptococcus pneumoniae in inhibition of ependymal ciliary beat frequency. Infect. Immun. 68:1557-1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohorst, H. J. 1963. Lactate, p. 267-270. In H. U. Bergmeyer (ed.), Methods of enzymatic analysis. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Kuo, T. L. 1982. The effects of ethanol on methanol intoxication. Jpn. J. Legal Med. 36:669-675. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marty-Teysset, C., F. de la Torre, and J. Garel. 2000. Increased production of hydrogen peroxide by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus upon aeration: involvement of an NADH oxidase in oxidative stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:262-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy, M. G., and S. Condon. 1984. Correlation of oxygen utilization and hydrogen peroxide accumulation with oxygen induced enzymes in Lactobacillus plantarum cultures. Arch. Microbiol. 138:44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole, L. B., M. Higuchi, M. Shimada, M. L. Calzi, and Y. Kamio. 2000. Streptococcus mutans H2O2-forming NADH oxidase is an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 28:108-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito, M., H. Kajiwara, T. Ishikawa, K. I. Iida, M. Endoh, T. Hara, and S. I. Yoshida. 2001. Delayed onset of systemic bacterial dissemination and subsequent death in mice injected intramuscularly with Streptococcus pyogenes strains. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:777-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito, M., S. Ohga, M. Endoh, H. Nakayama, Y. Mizunoe, T. Hara, and S. Yoshida. 2001. H2O2-nonproducing Streptococcus pyogenes strains: survival in stationary phase and virulence in chronic granulomatous disease. Microbiology 147:2469-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7173-7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stouthamer, A. H. 1978. Energy-yielding pathways, p. 389-462. In I. C. Gunsalus (ed.), The bacteria, vol. 6. A treatise on structure and function. Academic Press, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas, E. L., and K. A. Pera. 1983. Oxygen metabolism of Streptococcus mutans: uptake of oxygen and release of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 154:1236-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visser, J., H. Kester, K. Jeyaseelan, and R. Topp. 1982. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from Bacillus. Methods Enzymol. 89:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zitzelsberger, W., F. Götz, and K. H. Schleifer. 1984. Distribution of superoxide dismutases, oxidases, and NADH peroxidase in various streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 21:243-246. [Google Scholar]