ABSTRACT

In the context of a long-term institutional ‘twinning’ partnership initiated by Indiana and Moi Universities more than 22 years ago, a vibrant program of research has arisen and grown in size and stature. The history of the AMPATH (Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare) Research Program is described, with its distinctive attention to Kenyan–North American equity, mutual benefit, policies that support research best practices, peer review within research working groups/cores, contributions to clinical care, use of healthcare informatics, development of research infrastructure and commitment to research workforce capacity. In the development and management of research within our partnership, we describe a number of significant challenges we have encountered that require ongoing attention, many of which are “good problems” occasioned by the program’s success and growth. Finally, we assess the special value a partnership program like ours has created and end by affirming the importance of organizational diversity, solidarity of purpose, and resilience in the ‘research enterprise.’

INTRODUCTION

In the era of global health, when Northern Hemisphere universities have been described as “scrambling for partners” in Africa,1 we revisit the history of a North–South academic partnership in its 22nd year: how it came to be and—in the context of the Indiana Global Health Research meeting—how it came to include research. Twenty-two years may at first seem to be a brief history, but measured against other university ‘twinning’ partnerships only recently emerging (after ‘speed dating’ for funding opportunities) and even against the age of independent democracies in East Africa (in Kenya, 49 years since 1963), sustaining an institutional relationship of this duration is a significant achievement. In this paper, we report the history of this partnership and highlight research as one of its activities. It has been challenging to establish and maintain a research partnership that involves a large number of highly developed North American research universities and a new medical school in a developing country. In this paper, we describe the research partnership’s inevitable tensions and challenges and how they have been addressed to date. Finally, we end with an assessment of the program’s value.

PROGRAM BEGINNINGS AND EARLY HISTORY

Ramsey and Miller2 argue that academic medicine has a single mission—improving the health of the public—comprised of three interrelated submissions: education, research, and clinical service.3 This “tripartite” academic mission was fully embraced by the Indiana University (IU) Kenya Program in 1989 when it established a formal relationship with a new medical school in Eldoret, Kenya.4 The IU Kenya Program was built upon the same principles with which its founders also developed an academic general internal medicine program in an inner-city county hospital system in Indianapolis:

The program would support all aspects of the tripartite academic mission.

Health care would lead the way, but every clinic would be a classroom for teaching and a laboratory for investigation.

The collaboration would mutually benefit the health care providers from the medical school, the public hospital system in which they practice, and the patients they serve.

Decisions about care and quality improvement would be evidence-based, which would require systematic capture of data from the points of care via an electronic medical record system (EMR).

From the very beginning, faculty and trainees from the Indiana University School of Medicine were involved in clinical care activities at Moi University and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital. This was based on a philosophy of “leading with care,” making continual improvement in health care delivery a primary focus of every engagement. In addition to establishing an atmosphere of cooperation and trust (IU was not just there to benefit itself), high quality care is the mainstay of subsequent high-quality teaching and research.

During the first decade of the IU Kenya Program, the main academic focus was on education. Faculty members from the Moi University School of Medicine collaborated with their counterparts from the IU School of Medicine to develop a progressive, problem-based educational system for Kenya’s new (second) medical school.4 An educational exchange was established through which medical students and faculty from Moi University would travel to Indianapolis and participate in clinical and (for a few faculty) research while, conversely, medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty from Indiana University would round on the inpatient and outpatient (urban and rural) clinical services affiliated with Moi University. Within the first decade, additional U.S. medical schools and academic hospitals joined the IU–Moi University collaboration, including Brown University, the University of Chicago, Lehigh Valley Hospital in Pennsylvania, and Portland-Providence Hospital in Oregon.

A few research projects were performed in Kenya during the early years of this partnership, most often because they either (1) described or evaluated the educational programs at Moi University,5 (2) were performed by U.S. research fellows during their clinical rotations in Kenya,6 or were the result of U.S. faculty members participating in the research projects of their Kenyan colleagues.7

Two major occurrences resulted in research becoming a greater emphasis for the IU Kenya Partnership. The first was in 1997 when the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a new program entitled, “International Training in Medical Informatics” (ITMI), which aimed to increase the human capacity for developing and maintaining the infrastructure for health data collection and analysis to enhance research in developing countries.8 The ITMI program’s initial focus was sub-Saharan Africa to close the “digital gap” separating the developed and developing worlds. IU had both an enduring partnership in sub-Saharan Africa and an existing biomedical informatics training program in the Regenstrief Institute, a research entity closely aligned with IU.9 After securing ITMI funding, a delegation from IU and the Regenstrief Institute visited Eldoret, Kenya to identify partners in developing the ITMI training program. Together, these partners decided to train Kenyan faculty research fellows to (1) develop and sustain an ambulatory electronic medical record (EMR) system at a nearby community health center, and then (2) use this system to perform clinical research. Both steps were accomplished: in 2000 they established the Mosoriot Medical Record System (MMRS), the first ambulatory EMR in sub-Saharan Africa,10,11 at the Mosoriot Rural Health Center, a primary health care facility located 25 km south of Eldoret, which is used by the Moi University School of Medicine as an ambulatory training and research site. Once established, the MMRS was used by Moi University ITMI fellows to perform prospective research on outcomes of patients with acute respiratory illness12 and the antecedents and outcomes of traumatic injuries.13,14

The second major occurrence affecting the IU Kenya Partnership’s mission was a strategic decision in 2001 to initiate a comprehensive HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment program called AMPATH (originally the ‘Academic Model for Prevention And Treatment of HIV/AIDS’).15,16 A collaboration between Moi University School of Medicine and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH, Kenya’s second national hospital, located in Eldoret), AMPATH accepted responsibility for identifying and treating all of the HIV-infected persons in MTRH’s catchment area of 2 million persons. Not only did AMPATH expand the clinical service mission of the IU Kenya Partnership, it also needed an ambitious research and development enterprise because: (1) AMPATH’s leaders realized that managing an HIV/AIDS population estimated to be well in excess of 100,000 would require a comprehensive ambulatory EMR supporting both chronic disease management and research; and (2) most of the guidelines for HIV/AIDS care and prevention had been developed in North America and Western Europe and therefore had questionable relevance in a low-resource environment. Hence, an active research program would be required to develop and rigorously assess new, locally relevant approaches to care.

AMPATH opened its first clinics in 2001 at MTRH and Mosoriot, initially funded by a patchwork of philanthropic donations and small foundation grants. Major funding came in 2002 from the MTCT-Plus Initiative17 and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and from the Presidential Plan for Emergency AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2004.18 The Kenyan ITMI fellows and their IU and Regenstrief colleagues modified the smaller MMRS and, in 2001 launched the AMPATH Medical Record System (AMRS) to both serve AMPATH’s clinical mission and provide data for retrospective and prospective research.19 By 2002, AMPATH had opened HIV/AIDS clinics at three additional rural health centers and enrolled a total of 800 HIV-infected patients. At this point, AMPATH’s leaders decided that a formal research program needed to be actively developed and recruited two of the authors to lead it: the Regenstrief investigator (WMT) who directed the Moi–Regenstrief ITMI Fellowship Program and AMPATH’s Director of Paediatrics (WNN). At that point, there was little research infrastructure in place for this international collaboration in either Indianapolis or Eldoret, other than the aspects required to initiate ITMI fellows’ research projects. At this juncture a formal, systematic effort was enjoined to establish the AMPATH Research Program.

GROWTH OF RESEARCH AND SUPPORTIVE INFRASTRUCTURE

In recurring consultation with AMPATH’s North American and Kenyan clinical leaders, the AMPATH Research Program was based on the following core principles that closely echoed the underlying principles for AMPATH and the IU Kenya Partnership:

Care would always take precedence over research.

The AMPATH Research Program and each of its component parts would be co-led by a Kenyan faculty member of either Moi University School of Medicine or MTRH.

Relationships would be equitable and mutually beneficial.

Participation would be open to all organizations (universities and teaching hospitals) participating in AMPATH and the IU Kenya Partnership.

Long-term relationships would be preferred over short-term projects.

The AMPATH Research Program would strive to improve the health of the citizens of western Kenya while advancing medical science and investigators’ careers.

The AMPATH Research Program would support and enhance both facility-based and community-based care.

The AMPATH Research Program would establish a formal set of standard operating procedures (SOPs) and communication schemes to maximize collaboration and minimize confusion, conflicts, and disruptions.

When formally established in 2002, there was insufficient infrastructure to maintain a large, robust, multidisciplinary, multi-university, multinational research program. A single Institutional Research Ethics Committee (IREC) served both Moi University and MTRH. It had not been registered with the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections, and few of the other usual and necessary offices and policies for U.S. universities were in place. There was no office for managing grants and contracts. There was no research office to oversee and facilitate research in Kenya. Other than a Kenyan co-director (co-author WNN) and a U.S. co-Director (WMT), the program had no staff. There was no dedicated funding beyond that provided by the Fogarty ITMI fellowship grant and philanthropic donations to the IU Kenya Partnership. What did exist in abundance was need and a determination to make progress.

The first step was to recruit and train key personnel. This included U.S. and Kenyan Co-Field Directors of Research, U.S. and Kenyan research program managers, a financial officer, an IREC administrator, and a research assistant. Funding for the research program’s co-directors’ efforts came from the ITMI grant (by folding the ITMI fellowship program into the AMPATH Research Program), AMPATH’s clinical funds from two major sources (MTCT-Plus and a start-up grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and discretionary funds of the IU co-director. Together, these funds paid for faculty and staff salaries, training, travel, computers and other office equipment. In 2004, one of the authors (AMS), a former ITMI fellow, was recruited to be the Kenyan Co-Field Director of Research while Douglas Shaffer, MD took a sabbatical from his job at the Food and Drug Administration to serve in Kenya for one year as the U.S. Co-Field Director.

Together, these initial program leaders established policies and procedures for the protection of human subjects, which included obtaining Federal-wide Assurance for Moi University School of Medicine and MTRH and registering the IREC with the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections. They also established and managed relationships between AMPATH, Moi University, MTRH, and the North American investigators’ home institutions. They established regular teleconferences where overall management of the AMPATH Research Program was discussed, as were ongoing research projects and new opportunities. In 2003, they arranged a conference in Eldoret between IU and Moi University investigators and members of IREC and IU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to facilitate a coordinated cross-cultural review of all research protocols that resulted in a memorandum of understanding signed by directors of both IREC and IU’s IRB.20 To better understand Kenyan attitudes toward research, these initial AMPATH Research Program leaders performed a series of focus groups and structured interviews with primary care and HIV/AIDS patients, health care providers, and institutional leaders.21

In 2003, Doug Shaffer returned to the FDA and was replaced by two IU faculty (KWK and JES) who alternated their time between Indiana and Kenya. They developed numerous standard operating procedures, some of which are shown in Table 1. They established a system for storing key documents for each grant proposal and each funded project and established training programs for research program staff, data managers and analysts, and project staff. Most of these training programs occurred in person, requiring travel by content experts. Eventually, as Internet speed improved, remote teleconferencing was possible via sophisticated communication systems like Skype® and Elluminate-Live®. They oversaw the AMPATH Medical Informatics Program, including the AMRS and hand-entry data from thousands of paper encounter forms. . In 2006, a visiting NIH team establishing the Moi University AIDS Clinical Trials Unit certified AMPATH’s IREC and clinical laboratory. To accommodate increasing requests for data and analyses, in 2007 they developed the AMPATH Data Core and an electronic tracking system for study proposals and analyses.

Table 1.

Standard Operating Procedures

| Backing up data | Managing grants and contracts |

|---|---|

| Conducting research in AMPATH clinics | Monitoring data |

| Developing AMPATH encounter forms | Obtaining AMRS data |

| Developing collaborative research | Performing student research |

| Establishing authorship | Reporting patient deaths |

| Faculty and staff travel | Reporting to external agencies |

| Hiring research personnel | Writing and getting SOPs approved |

| Hosting visiting students | Writing and submitting grant proposals |

| Including students and trainees in research | Writing and submitting publications |

| Maintaining data quality | Writing and submitting presentations |

AMPATH Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare; AMRS AMPATH Medical Record System; SOPs Standard Operating Procedures

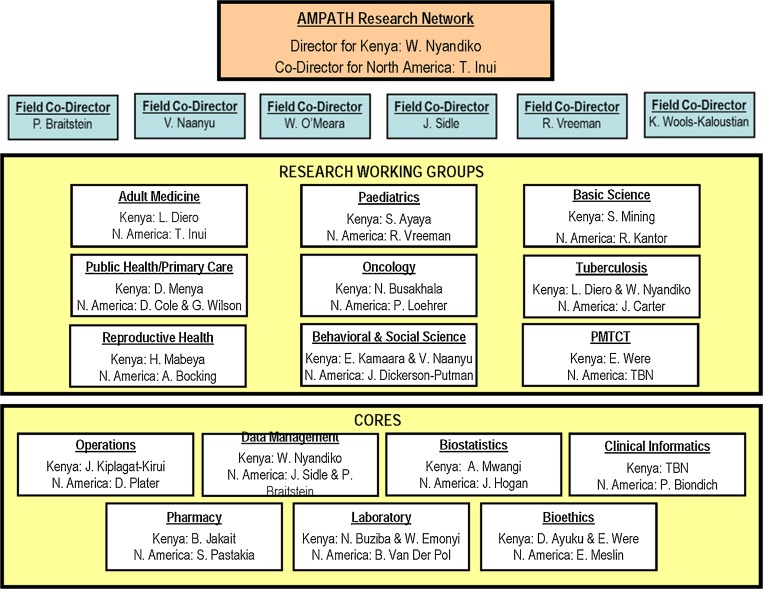

By 2006, these two individuals were overseeing a burgeoning number of research projects, while also developing their own individual research programs. It became clear that a new level of oversight and management was required. After much internal discussion, the number of co-field program directors of research was gradually increased from two to six, with three living full-time in Kenya. A new organizational structure was designed in which ten specialty-focused Research Working Groups were supported by seven Cores. This new organizational structure is shown in Fig. 1 in its current instantiation. Each Research Working Group and Core is co-led by a Kenyan and North American faculty member and each is expected to have a clear mission and near-term goals and objectives, hold regular teleconferences, and report monthly via e-mail and teleconference to the AMPATH Research Network’s co-directors. Each project must complete a short biannual report form to update AMPATH’s leaders on their goals and progress, which the Kenyan and North American research program managers use to generate a Biannual Research Report for AMPATH’s leaders.

Figure 1.

Organizational structure of the AMPATH research program.

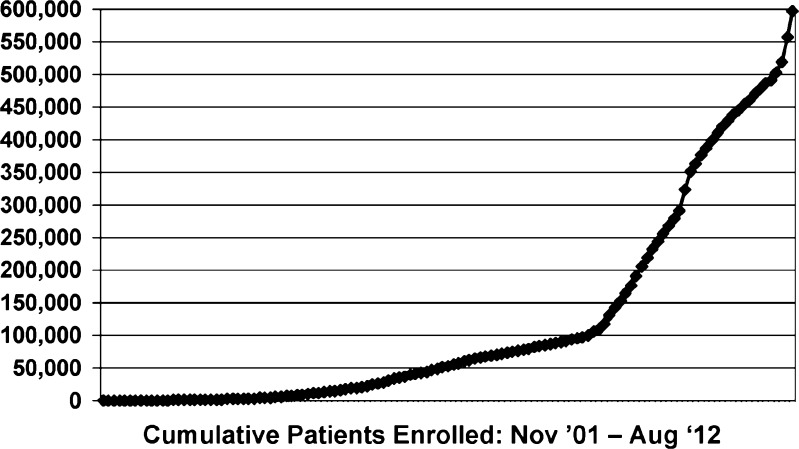

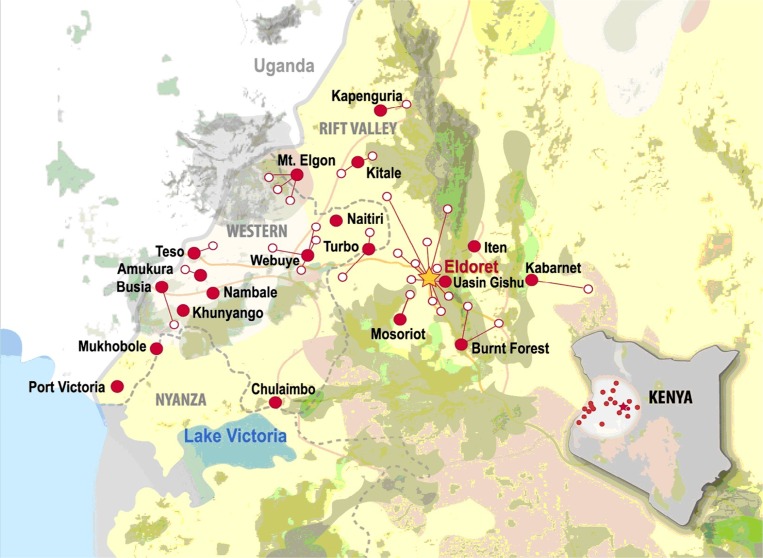

One key goal was to establish a formal practice-based research network in AMPATH clinics where onsite recruitment would be facilitated by using AMRS data to identify potentially eligible subjects and having onsite research assistants who recruited for multiple studies. This started with a single AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) study, which then allowed AMPATH to become an ACTG international research site, which in turn led to additional studies funded by government, foundation, and industry funding agencies. This network was directed by one of the authors (AMS) and was modeled on a successful EMR-based practice-based research network established in Indianapolis by one of the authors (WMT).22 The AMPATH Research Network took advantage of the rapid growth of AMPATH patient enrollment as shown in Fig. 2. By the end of 2006, AMPATH had expanded to 16 sites in urban and rural western Kenya and had enrolled more than 45,000 HIV-infected patients. Currently, there are more than 600,000 patients enrolled in AMPATH—more than 160,000 with HIV/AIDS—who receive care at 25 Ministry of Health Centres and 46 satellite clinics (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

AMPATH patient enrollment.

Figure 3.

AMPATH Ministry of Health centres in western Kenya.

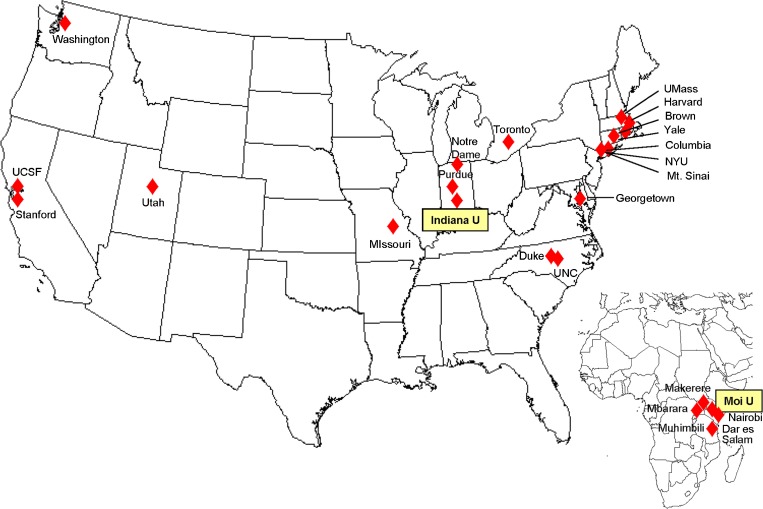

Such rapid growth in clinical services created many opportunities for performing practical, cutting edge clinical research. As AMPATH’s success in enrolling and managing HIV-infected Kenyans and practice-based research network became known, an increasing cadre of investigators from AMPATH’s current North American partner universities became interested in performing research in the AMPATH Research Network. As a result, an increasing number of project ideas were developed and grant proposals submitted. In addition, investigators from other universities inquired about opportunities for performing their research in AMPATH sites in Kenya. These latter requests were often denied unless they were part of a more long-term commitment to one or more (preferably more) AMPATH mission. In spite of this selectivity, over time the number of North American universities actively engaged in the AMPATH Research Program grew steadily. In addition, AMPATH investigators received funding through a NIH HIV/AIDS epidemiologic research program entitled International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA)23 to become the IeDEA reporting agency for East Africa. This brought to the AMPATH Research Network five additional East African universities. (The North American and East African universities currently engaged in the AMPATH Research Program are shown in Fig. 4.)

Figure 4.

Universities participating in the AMPATH research program.

The amount and diversity of data collected by clinical and research activities grew exponentially. A patchwork of PhD and masters-level biostatisticians were engaged to support individual projects, but there was no centralize system for processing requests for data management and analysis. So in 2008, the AMPATH Data Management Core (co-led by two North American Co-Field Directors of Research living full-time in Kenya) and the AMPATH Data Analysis Team (led by biostatistician Joseph Hogan from Brown University) were created with core funding from AMPATH and the Regenstrief Institute. They established systems for receiving and vetting requests for data and analyses and for tracking progress from request to analysis to publications. They also established training and mentoring programs for North American and Kenyan data managers and analysts at all levels.

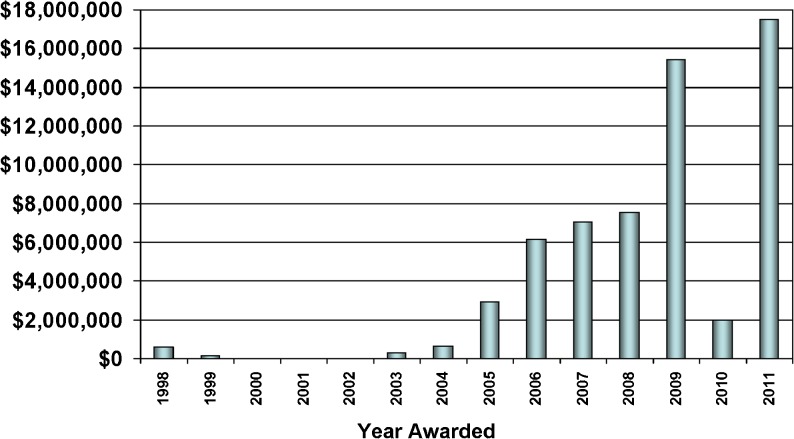

The growth in AMPATH’s number of clinical sites, clinical and support programs, and enrolled patients provided ample opportunities to compete for research funding. As shown in Fig. 5, after a slow start as the research infrastructure was built, cumulative extramural funding from research and training grants and contracts has grown to exceed $65 million. To date, more than 186 articles have been published in peer-reviewed journals, and in many cases research results have impacted AMPATH’s health care delivery processes and outcomes. Yet despite the rapid rise in extramural support, the research program’s infrastructure was not adequately funded. The indirect costs to North American universities was not applied to the infrastructure in Kenya, and as mentioned below, the 8 % indirect cost recovery allowed by NIH for foreign institutions was not adequate to support the breadth of this multidisciplinary clinical research program. There were significant overlaps between clinical and research needs. For example, the reference laboratory was required for both clinical care and research, and funding agencies required the same detailed information about health care delivery as did the research enterprise. Therefore, some funding of the research infrastructure, including salaries of management personnel, came from grants and contracts supporting clinical care. That was still insufficient, and AMPATH’s Research Director (WMT) invested more than $120,000 of his own discretionary funds to develop the research program and avoid losing talented staff.

Figure 5.

AMPATH research network funding.

Establishing and Managing by Strategic Objectives

Success and growth in the AMPATH Research Program also triggered the need for clarification of the research program’s mission and recognition of program priorities in strategic planning. In January 2010, the first all-stakeholder AMPATH Research Program retreat was held to discuss priorities. More than 50 potential emphases emerged as potential program priorities, a rich but too-broad agenda for administrative management. In October of 2010, a program leadership transition took place, passing co-directorship of the program in North America from Dr. Tierney to Dr. Inui. Apart from this change in personnel, for the first time a core budget was established to support program infrastructure from the North American side. Six months into this new leadership term, a consensus arose that a small set of program priorities should be identified in order to strategically allocate resources (administrative effort and core funding).

In a several-round Delphi process a program mission, vision, and values statement was adopted (Fig. 6). After pre-retreat interviews of important stakeholders among North American and Kenyan principals, a one-day retreat was held in July, 2011 to codify these priorities. The retreat itself was divided into two segments. In the morning, four small groups of retreat participants reviewed the January 2010 emphases, and multi-vote polls were conducted to arrive at relative importance weights. At midday, the 13 most highly rated emphases were identified on the basis of these weights and three to four were assigned to small groups for further discussion and delineation of a developmental “roadmap” to track progress going forward. After the retreat, these 13 priorities were presented to Moi University of School of Medicine and AMPATH Clinical Program leadership for their understanding, discussion and feedback.

Figure 6.

AMPATH research program mission, vision and values statement.

Program goals emerging from the retreat are summarized in Table 2 (Research Strategic Priorities-Goals and Activities). Strategic priorities appear in Table 2 as “activities,” and are grouped under four goals: (1) enhance investigator research capacity, (2) improve research coordination with other institutional areas, (3) strengthen Kenyan collaboration within the AMPATH Research Network, and (4) ensure the sustainability of the program. The first goal emerges from the shared recognition (Kenyan and North American) that Kenyans have too often functioned in secondary roles rather than leadership positions in individual projects and in the program overall. This kind of “subdominant” Kenyan positioning materialized in spite of the research program’s emphasis on parity and partnership. Whatever the program’s espoused ideology had been, the limited number of fully prepared Kenyan investigators at Moi had been too small to support equal leadership. Additional human capacity development thus became a first priority. In non-personnel terms within this same strategic priority, discussions focused on the need to grow an enhanced capacity in the AMPATH Reference Lab, a facility that supports both research and non-routine clinical diagnostic tests in the Moi/AMPATH environment. In the clinical program management/implementation research “overlap domain” of Monitoring and Evaluation, Goal 2 includes support for clinical program briefing within research working groups, as well as engagement with policy makers within AMPATH and the Ministry of Health. Goal 3 emphasizes the need for committed time in the schedules of Kenyan investigators to participate in the processes of research, the intent to enhance Kenyan investigator participation in research working groups, and the need for advanced training in research methods among Kenyan investigators. Finally, Goal 4 (sustainability) acknowledges the need to communicate the value of research to research program stakeholders, diversify funding sources for research, and communication of research findings across a broad array of domains to clinical program leadership. As articulated, these priorities were understood and embraced by leadership of the Moi University School of Medicine, MTRH and AMPATH.

Table 2.

Research Strategic Priorities - Goals & Activities (Condensed Voting Summaries from the June 2011 Research Retreat) Foundational Actions Required for All Other Progress: 1. Consensus on Research Program Mission and Vision. 2. Additional Dedicated Space for Research Activities

| Goals | Objectives | Activities | Priority rank order (of 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invest in greater research capacity | Expand and develop research personnel and human capacity | Invest in more research training, especially for registrars, medical officers, and MPH graduates | 1 |

| Increase data and biostatistics support | 7 (tie) | ||

| Priority points assigned (100 possible points): 33.25 | Strengthen laboratory infrastructure | Improve laboratory capacity (tests, technology, IT, people) | 7 (tie) |

| Plan for expansion and apply for infrastructure grants and other enhanced funding | 5 | ||

| Improve Research Program’s coordination with other institutional areas | Integrate clinical research with programs of clinical care | Build M&E into all clinical programs and program roll-outs, including baseline evaluations | 12 |

| Strengthen working groups to focus on both clinical and research topics | 6 | ||

| Priority points assigned: 19.75 | Translate research into policy changes | Engage the MOH on their research needs and priorities; offer research assistance on implementation questions | 13 |

| Strengthen Kenyan collaboration within the AMPATH Research network | Strengthen research opportunities, training, and coordination for Kenyans | Strive for protected time for Kenyan investigators | 2 |

| Priority points assigned: 22.25 | Create more equal Kenyan/North American involvement in research activities | Improve Kenyan involvement in Working Group (brain storming at the beginning of the WG meeting; moving forward Kenyan-centered ideas) | 10 (tie) |

| Become a center of excellence for training in health research | In 5 years: leading and hosting a Diploma in Research Methodology—income generating activity for research program | 10 (tie) | |

| Ensure the sustainability of the research program (community, funding, organization) | Improve research program’s relationship with the community | Communicate benefits of research to the community and receive feedback, addressing identified problems | 4 |

| Priority points assigned: 24.25 | Diversify funding sources to ensure future sustainability | Analyze current research funding sources and seek to find new sources that are more diverse | 3 |

| Improve research policies and organizational structure to support the mission | Increase research focus on issues broadly relevant to the health of Kenyan populations (e.g., malaria, TB, chronic diseases, and more health services research) | 9 |

MPH Master of Public Health; M&E monitoring and evaluation; MOH Ministry of Health

A Bestiary of Challenging Issues

“Problems worthy of attack, prove their worth by attacking back.”

[from Grooks, Piet Hein, 1966]

In the process of research program management, some issues have proven to be ‘sticky wickets,’ requiring constant attention and episodic active problem-solving. These challenges have included:

-

Maintaining equity/fairness within the partnership

Several different asymmetries have posed challenges to equity and raised issues of fairness our North–South partnership. These asymmetries include differences in income time flexibility, faculty size and expertise. Differences in levels of compensation prevail in North–South partnerships and may not be fully offset by differences in cost-of-living. When applying for grants, the compensation for the Kenyan researcher was based on the normal basic university or hospital salary, a level of compensation that was meager compared to their American counterparts. Until recently, these glaring differences in ‘university’ salaries meant few Kenyan faculty could afford take time away from their relatively lucrative private practices to commit to research. Those who did make this decision were engaging in personal sacrifice. Since 2011 the adoption of a Moi University standard for research compensation has minimized this disparity. Differences in social and family responsibilities, however, also exact a toll, since Kenyan faculty by culture and tradition have larger extended families for whom they assume financial and other responsibilities. A single faculty member may provide direct support for as many as 50 family members, and there are many non-financial obligations that arise in such an extended kinship. As one faculty member has noted: “It seems to me that I go out of town for a funeral every weekend.”

North American faculty may have ‘protected time’ for research. While older U.S. investigators only have time available to commit to research if they have secured grant support to fund this time, young investigators may actually have time funded for several years by their institutions as part of their ‘start up’ package. Kenyan faculty have no such funded time and have to extract time for research from many other commitments, including teaching, university examinations, governance, and clinical practice activities. Because Moi department faculty are smaller in size, teaching, examination and governance duties are not readily shouldered by others if one faculty member wishes to carve out personal time for research, even if this time is to be funded by a grant. There are no ‘research faculty tracks’ at Moi. Unlike in North America where faculty can be predominantly in the research track and spend relatively little time spent in clinical care and teaching, the few ‘research-oriented’ Moi faculty members have to perform all three core responsibilities and are expected to have output like all their colleagues in each of these domains. Additionally, the Kenyan faculty who are interested in research are often in administrative positions within the university structures (including department chair, dean, and program manager positions). The governance and administrative management responsibilities in these positions often mean that even less time is available for research. Kenyan faculty members with interests in research become ‘spread too thinly’ across the sectors of their professional responsibilities. This situation has led to a movement at Moi to increase the number of faculty in each department using the normal university staff mechanisms.

Finally, at this point in history, Moi faculty interested in research have less often been fully trained in research methods than is the case of the North American faculty doing research in Eldoret. This asymmetry in expertise and experience leads to more passive participation in collaborative research by the Kenyans. To compound the matter, lesser Kenyan investigator experience in research impairs their capacity to write competitive grants, abstracts, and manuscripts for publication. Success in securing NIH-funded research fellowships and investment of North American time in coaching and mentorship have been important approaches to ‘leveling the playing field’ in the research enterprise, including current efforts to train more faculty in basic research, research ethics and clinical trial methodology.

-

Maximizing alignment and synergy within the North/South PI dyads

Maximizing synergy within the North America and Kenya principal investigator dyads has remained a challenge. The AMPATH Research Office and, increasingly, the AMPATH research working groups play a critical ‘match-maker’ role in bringing potential principal investigators together. North American PIs depend on the Kenyan investigators to know the working clinical, laboratory, or data management program environment, envision the logistics and operations of a new project, and subsequently to manage the project ‘on the ground.’ North American investigators often bring project-relevant methodologic and technical expertise, knowledge of key consultants from transnational research networks, and experience with their home universities research administrative policies and resources. The potential for synergy, given these complementary individual expertise bases, is substantial. Disagreements between the members of the principal investigator (PI)-partnered dyad, however, occur in the conduct of research when both PIs do not identify and work to resolve issues that arise in the project. Some of these issues have included meeting commitments, role expectations, budget management, authorship, personnel performance assessment, resolving differences in human subjects review group recommendations, and identifying and supporting other potential collaborators at Moi. Research team formation and management is not a well-codified domain of knowledge anywhere and remains a work-in-progress in AMPATH research.

-

Supporting the ‘absentee’ PI (the North American who is not on the ground in Kenya)

As a program, we deliberately set out to ensure that all collaborators from outside Kenya have contact with the activities in Kenya as often as humanly possible. We believed that a totally ‘absentee researcher’ would simply not understand the complex cultural and system challenges ‘on the ground.’ Most researchers from North America, therefore, do commit substantial time to visits in Kenya, often residing in Indiana University dormitory-like compound housing with other faculty, students, and residents. Even given this special effort, the Kenyan co-PI often still has to sort out many urgent requests and research logistical, ethical, personnel and human subjects issues, including staff salary setting, transportation, procurement, subject withdrawal, and protocol breeches. On balance, having a North American investigator spending less than 40 % of his/her time in Kenya where the research activities are carried out has been a challenge. Experienced Kenyan study coordinators, who are now mandatory personnel on all projects, have helped in closing the “gap” left by the absentee PI by being a key project manager and ‘right hand’ for both the North American and Kenyan co-PIs in the day-to-day running of project activities. Email communications and conference calls held at least once in a month between North American investigators and Kenyan study team, to keep each other up to speed on what goes on in the study, have helped alleviate problems posed by the absenteeism.

-

Building the Research culture at Moi

Because most Kenyan medical faculty have taken their training at in-country universities where they had limited focus on research as a part of university academic culture, there is no strong historical tradition of research as an essential element in university affairs at Moi. Much of this lack of ‘research culture’ materialized in an environment in which there were limited grant opportunities and the major source of income among health professions faculty in Kenya was private practice. The Kenyan faculty at Moi is only now beginning to appreciate that research is an equally appealing area of professional effort, especially the younger faculty. It is, however, requiring a deliberate effort by Kenyan leadership to create research mentorship panels and to identify and attract young faculty to research careers. In the development of this institutional culture, momentum has been added by the faculty and administration noting that the reputation of Moi University has been nationally and internationally enhanced by research publications. The administration and leadership in individual departments now are developing strategies to increase competitiveness for grants and to support publications. They have introduced Research Medical Officer positions at AMPATH in an attempt to encourage young doctors to consider research as a career in future. Intramural funding for faculty pilot projects has become available in the Moi School of Medicine. Financial support for residents with good research concepts, especially so those that may be in line with on-going research projects, has been made available. In academic departments and within AMPATH research working groups, encouragement and support are provided to faculty who write concept proposals as sub-studies of major extramural grants already awarded to Moi. Explicit efforts are made to expose more of the older faculty to local and international research conferences of relevance to their clinical expertise.

-

Aligning research with the AMPATH clinical mission

As one activity of a ‘leading with care’ system, the AMPATH Research Program is embedded in an evolving health care delivery system with information needs and operational challenges. This system should regularly benefit from new knowledge of relevance to its challenges developed by AMPATH researchers. We have come to think of AMPATH as a “learning organization” and its research arm as engaging in activities that shed light on and perhaps offer guidance to clinical program leadership in their decision making.24 This orientation has come to be described as “managed implementation research” by AMPATH leadership. Maintaining good communication between clinical and research program leadership at all levels while avoiding conflicts between clinical and research aims and activities is an ongoing challenge. Integrating research processes that unfold over years with clinical program improvement that can unfold over months is an art form.

-

Managing expectations within the AMPATH Consortium

In North America, investigators from fifteen universities participate as principal investigators for projects within the AMPATH Research Program. This “AMPATH Consortium” operates as a voluntary federation of academic medical centers with interest in education, service, and research in the AMPATH environment. The Consortium operates largely without written standard operating protocols for its activities and has regularly added new institutional members over time. AMPATH Research Program standard operating procedures (SOPs) for research at Moi do help to align and standardize the activities of principal investigators within the AMPATH Consortium. AMPATH clinical program achievements, data, and problems attract problem-oriented investigators to particular topics for research within AMPATH. The potential for competition in response to funding opportunities among consortium member investigators in response to particularly attractive RFAs always exists, and at times conflicts have arisen that had to be mediated by research program administration.

-

Dealing with compliance issues (compensation, time commitment, conflict of interest)

Various institutional compliance issues are critical to resolve in an international as well as a domestic setting if partnership programs of research are to be fully aligned with research best practices and sponsor policies. Achieving compliance in each of these policy domains has been a major achievement. It was not until 2011, for example, that we were able to establish university standards for compensation for Moi faculty for their participation in research. These compensation rates had to be anchored in Kenyan labor and tax law and findings from the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) recommendations for allowable compensation of university faculty consultative activities. Conflict of interest and time commitment policies are still emerging, because no institutional standards for these matters are automatically important in the Kenyan university context, where faculty members are compensated for teaching and governance participation, but are free to earn whatever they can from private practice or consultation without direct university oversight or constraints.

-

Harmonizing human subjects issues across settings in North America and Kenya

All proposals for research are reviewed by both Kenyan and North American IRBs. For reasons of efficiency and enhancing mutual understanding, efforts were made recently to create a new joint ethics review committee to which Moi and IU collaborative proposals would be submitted for review and approval. The new committee was to be the first of its kind in that it would be a stand-alone committee with shared leadership, and membership from both universities. It would have streamlined the review process without compromising ethical standards. The proposal failed to garner the support of Kenya’s National Bioethics Committee and has been shelved for now. Therefore, all research proposals continue to be reviewed independently by the Moi IREC and the IU IRB. The IREC reviews proposals for scientific merit as well as for research ethics considerations, while the IU IRB attends to research ethics primarily. Both bodies communicate their findings and recommendations to the principal investigators, but do not consider the findings of the other institutional committee germane to their discussions or findings. As might be anticipated, this ‘dual channel’ process has led to differences in emphases, findings and recommendations that the dyadic Kenyan–American principal investigator dyads must struggle to reconcile. Differences in turn-around times for reviews are routine. The IU IRB takes about 2 months to come to a final resolution on a protocol, including time for first review, consideration of investigator response, and final review. The Moi IREC typical turn-around time is 4–5 months, on the other hand, and reviews have been known to require 8–9 months to be consummated. Under these circumstances, both integration and synchronization of human subjects considerations in research projects is challenging. Differences in recommendations driven by cultural perspectives have been relatively infrequent, but have arisen, since such basic differences as the composition of families (polygamous versus monogamous), the autonomy of women, and the age of adulthood prevail between Kenya and North America.

-

Identifying and managing authorship issues

Authorship issues, and at times controversies and conflicts, are common in busy academic research environments. The nature of collaborative research requires different amounts and types of efforts among research team members. If authorship responsibilities are not specified up front, disagreements can occur, inflamed at times by the importance of first-authored and senior-authored publications in investigators’ academic promotion and tenure decisions and enhancing their professional visibility. Given the size and complexity of the AMPATH Research Program, involving investigators from more than 15 universities who participate in ten AMPATH Research Working Groups, there is ample opportunity for miscommunication and differences of opinion about authorship.

The possibility of conflicts around authorship issues was identified in the early days of the AMPATH Research Program. To help minimize these, its leaders developed a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Publications that included a process for determining appropriate authorship. By the terms of this SOP, prospective authors are required to fulfill the criteria for authorship published by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)25 that have been espoused by most major medical journals. These authorship guidelines state that all authors must meet all of the following three criteria: each author must 1) make substantial contributions to the conception and design of a study, aid in the acquisition of data, participate in the analysis of the data, or help interpret the results; 2) aid in drafting or revising the manuscript; and 3) approve the final submitted version to be published.

Second, if relevant each manuscript must be read and approved by the Principal Investigator of a study from which the study data were derived and the director of a relevant clinical program, whether or not these individuals are authors on the manuscript. This rule recognizes the role of the PI and program directors as leaders and participants in the work of the research, and requires both individuals to make sure that the manuscript adequately and appropriately describes the environment and overall research results. An important, additional part of the PI’s and program director’s role is to make sure that the byline includes all appropriate authors and that the rank order is correct.

Third, after approval by the PI, the manuscript is submitted to the AMPATH Publications Committee, chaired by AMPATH’s Co-Directors of Research and comprised of a small set of Kenyan and North American investigators. Communicating via an e-mail listserve, the Publication Committee expeditiously reviews all manuscripts and material for oral and poster presentations, approving both authors and content.

-

Establishing and maintaining financial administration in the U.S. and Kenya

The AMPATH Program, including its research, found it necessary to establish a federally qualified grants and contracts office within the Kenyan institutional context in order to establish sound policies and practices for accountable management of grants, whether these grants were in support of the clinical delivery system or for research. No such office preexisted AMPATH’s existence and no traditions of regular audits and routine reporting were present before various North American sponsors, particularly the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) made these requirements explicit and sponsored audits to assure compliance.

-

Sustaining support of the research infrastructure

Securing a revenue stream for administrative management costs in an international setting is challenging. The NIH and other federal sources for research in North America permit only 8 % in indirect costs. To our knowledge, this rate bears no known relationship to actual institutional costs, which are apt to be much higher (even in settings with lower personnel and material costs). This means, in effect, that both North American and international institutions subsidize the total costs of research activities, requiring identification of funding from endowment or philanthropy to assure sustainability. In particular, inadequate indirect cost revenues adversely affect support of space for research, development of information management systems, and human subjects review offices.

-

Managing space and assuring security

Moving from one funded study in 2004 to over 110 funded studies by 2012 has been a great achievement, but a transition that has challenged research management to find and secure additional space. Within the AMPATH Centre, space for both research and clinical care had been earmarked, but with the growing numbers of patients enrolled for care and an increase in grants awarded, space became inadequate to need and demand. The AMPATH Research Program office must now continuously seek space outside AMPATH’s academic campus to accommodate research projects that already have funding but lack space to accommodate personnel and supplies. Similarly, completed projects with requirements for data and forms secure storage for 3–7 years are beginning to require still more space. Most studies do not budget for this resource. All space, whether for current projects or data storage, imposes a need for physically secure buildings, guards, alarm systems, uninterruptible power sources, and internet access. Having double locks in offices is not enough for security. Desktop computers and laptops have been stolen in some cases, calling for more secure ways to be invented. Putting all paper records under lock and key in facilities accessible to only research staff, and password protection or encryption of all research-related data, has been key in ensuring security of data.

-

Coordinating communications and decision-making across time zones

Synchronous communication and decision-making across widely disparate time zones is challenging, particularly with a seven or eight hour time zone difference between East African Time and Eastern Standard or Eastern Daylight Time in North America. Because working groups, programs, and projects are organized as partnership activities that include Kenyans and North Americans, this means that the “window” for teleconferencing is small. Most of the 57 monthly teleconference meetings joining Moi faculty and North Americans take place in the early morning hours in North America and late in the afternoons in Kenya, not always the optimal times for participants to make critical decisions together.

Asynchronous communication between North American and Kenyan dyads is often conducted by email, with its attendant risks of content misunderstanding and impoverished communication of affect. Given a slow email connection in Kenya that is often down and the busy schedules of Kenyan researcher/clinician/educators, there are delays in responses that may adversely affect decision making for research. Improved email access, less international telephone charges and use of Skype have all partially addressed this challenge, but limited bandwidth, power outages, and ambient noise during rainy season torrential rainstorms all continue to pose challenges.

-

Managing North–North partnerships

Most descriptions of global health partnerships focus on managing expectations and logistics among North–South collaborations. Yet just as challenging were managing expectations and commitments among the participating institutions in the U.S. and Canada. AMPATH leaders were frequently approached by investigators from North American institutions, often with funding in hand and looking for a suitable and supporting venue within which to conduct their research. AMPATH’s engagement philosophy eschewed “parachute research” and instead required a commitment to a longer-term inter-institutional relationship before considering individual research projects. Moreover, North American researchers had to accept AMPATH’s principles of mutual respect and benefit, leading with care, co-leadership of all programs and initiatives by Kenyans and North Americans, and following all SOPs and the reporting structure as embodied in AMPATH’s organizational chart. Investigators had to be willing to follow the basic principles of the agreement between Moi University’s and Indiana University’s IRBs. Each North American institution identified a lead investigator who served as the primary contact person with AMPATH. Active participation in communication activities, mainly teleconferences and e-mail listservers, was expected.

Recommendations Based on the AMPATH Experience

The AMPATH Research Program has achieved remarkable success, far beyond what was anticipated by its leaders at its inception in the early 2000s. Yet its continued existence and future success would benefit from, and to some extent depend on, ongoing development and continuous improvement. We therefore make the following recommendations, ones that we believe are relevant to all North–South research partnerships:

-

Document the research program’s principles

AMPATH’s core principles guide all subsequent relationships and SOPs. All global health partnerships should be based on a core set of principles, and these principles should be clearly documented and adopted by all institutions and investigators engaged in the research partnership.

-

Establish a consortium of research partnerships

North–South research partnerships need to evolve and strengthen to enhance global health research and accelerate the pace at which evidence can be applied to the critical needs of the global South, while creating mutual benefit of all participating institutions. There is no blueprint or roadmap for moving forward. Principles will serve as a foundation for standard operating policies. Regular assessments of strategies and progress in the spirit of continuous improvement will be required. Peer-to-peer learning could be key to sharing best practices and solutions that work.26

-

Increase indirects paid to foreign institutions

The 8 % indirect cost recovery allowed to foreign institutions does not come close to paying the true cost of maintaining foreign institutions’ research infrastructure. Therefore, institutions in developing countries like Moi University have to pay more to support U.S. federally funded research than AMPATH’s North American universities must pay. Forcing institutions in low-income countries to subsidize NIH research is unconscionable. We urge the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to allow foreign institutions to calculate facility and administration (F&A) costs in a manner identical to that allowed within U.S. nonprofit institutions.

-

Implement a research infrastructure fee

Cost recovery through federal research grants is guided by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.27 These rules recognize that there are research infrastructure costs that are not included in indirect cost calculations, but which are difficult to charge piecemeal to individual grants and contracts. They therefore allow the creation of “specialized research facilities” for which a charge structure can be established. Such infrastructure is required by all North American investigators performing research in developing countries and so all research projects should support it. Without such a fee, the infrastructure will never be sufficient to fully support high-quality research. IU has established such a fee structure on behalf of the AMPATH Research Consortium. Other institutional networks should do the same.

-

Consider establishing a joint IRB

Especially when there are multiple universities involved in either the developed or developing world, managing human subject protection through individual IRBs is both very time-consuming and fraught with difficulties managing expectations and communications. Training on both sides that is highly relevant to collaborative global health research is often incomplete and inconsistent. A fully empowered joint IRB based in the developing country would mitigate these difficulties while not relinquishing control by either partner. Trust and cooperation at all levels—investigators, universities, governments—is necessary to establish a joint IRB.

-

Establish compliant salary payment mechanisms

The manner in which North American investigators’ salaries are maintained and compensated by grants and contracts is quite consistent across institutions. That is not the case among academic investigators in various developing countries, so the explicit salary structures and expectations for compensation by research funds must be clearly delineated. Existing payment mechanisms in developing country universities may not be consistent with U.S. federal regulations, in which case significant changes in salary structures may be required. This takes time, cooperation, and institutional accord. Discussing this matter early at the highest levels of university governance (e.g. Dean, Chancellor) should occur early in an emerging partnership.

Finding Values in Our Research Partnerships – What are They and Why are They Important?

With as many challenges and difficulties as we have described in the preceding section, what have been the benefits realized in this research program partnership that, on balance, make muddling through worthwhile? In response to this question, one of the Kenyan co-authors of this manuscript drafted the following list of reasons why research is valued in the Moi/AMPATH environment:

Increased funding for infrastructure development (laboratory, research space, communication, procedure management)

Increased Kenyan human research capacity through training

Faculty promotion

Increased national and international recognition in research domains of interest

Increased networking and research/grant opportunities in the region

Improved capacity for cross-cultural communication, tolerance and mutual support

Improved care guidelines arising from health services research

Increased contextual adaption of tools and procedures

Improved population health

The rest of the authors, North American and Kenyan alike, would affirm this list as applicable to both partner environments—these effects are felt and valued at Indiana as well as Moi University. Faculty and graduate trainees from Indiana might add a few additional considerations. Doing research in Kenya and engaging with others in the global networks involved in HIV research or focused on research in low-income and middle-income countries has substantially enhanced the ethnic, racial and cultural diversity of our North American ‘university community’ beyond what might have otherwise been possible had we ‘stayed behind our walls’ in Indiana. The professional networks in which we embed our careers have been greatly enhanced by the work we do in Eldoret. Our opportunities for research have been substantially expanded by being part of a data-rich learning system focused on the care of people with HIV, tuberculosis, and non-infectious chronic diseases. Finally, our opportunities for personal professional rewards derived from a commitment to improving care for vulnerable populations have been enhanced by the ‘service’ we do within AMPATH as participants in care, care improvement, and research.

Recognizing these positive effects of research and becoming explicit about why this research partnership seems to us to be valuable to our university communities is useful. Beyond whatever the individual personal and professional values these activities express for each of us, we would contend that no research organization today can be entirely self-sufficient or isolated from what is transpiring in research elsewhere. Given the global increasing capacity for rapid dissemination of new information and best practices, all learning organizations devoted to activities like research on cost-effective care for people living with HIV should be interdependent and actively learning from one another, as well as from their own experience. Partnering across differences (North–South geography, resource-scarce and resource-replete societies, black-dominated and white-dominated demographic locales) and affirming the importance of issues we have in common (maximizing health, maximizing efficient use of resources, and minimizing disparities in access and health, for example) assures diversity within our AMPATH research human and intellectual community, as well as solidarity of purpose. In nature as well as social processes, diversity confers resilience, and in the face of challenges like those we have encountered, research communities need both resilience and solidarity. Fortunately, both of these qualities were part of our AMPATH birthright and have been constantly reinforced by the march of history in which we have participated.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the clinical and research staff of the USAID-AMPATH Partnership for their continued support of our efforts to improve the quality and outcomes of care in western Kenya. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their respective institutions or the agencies that have funded AMPATH research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crane J. Scrambling for Africa. Lancet. 2010;377:1388–1390. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61920-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsey PG, Miller ED. A single mission for academic medicine. JAMA. 2009;301:1475–1476. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The handbook of academic medicine: How medical schools and teaching hospitals work. 2. Washington: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einterz RM, Kelley CR, Mamlin JJ, Van Reken DE. Partnerships in international health: The Indiana University-Moi University experience. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995;9(2):453–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Einterz RM, Goss JR, Kelley S, Lore W. Illness and efficiency of health services delivery in a district hospital. East Afr Med J. 1992;69(5):248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wools K, Menya D, Mulli F, Jones R, Heilman D. Perception of risk, sexual behaviors, and STD/HIV prevalence in women attending an urban and a rural health center in Western Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(12):679–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menge I, Esamai F, Van Reken D, Anabwani G. Paediatric morbidity and mortality at the Eldoret District Hospital. Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(3):165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilenz J (Ed.).Fogarty at 35. Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/News/Documents/history-fogarty-at35.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2013.

- 9.Ford W. Regenstrief: Legacy of the Dishwasher King. Indianapolis: Regenstrief Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannan TJ, Rotich JK, Odero WW, et al. The Mosoriot medical record system: Design and initial implementation of an outpatient electronic record system in rural Kenya. Int J Med Informat. 2000;60:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(00)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotich JK, Hannan TJ, Smith FE, et al. Installing and implementing a computer-based patient record system in sub-Saharan Africa: The Mosoriot Medical Record System. J Am Med Informat Assoc. 2003;10:293–303. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diero L, Rotich JK, Bii J, Mamlin BW, Einterz RM, Kalamai IZ, Tierney WM. Using a computer-based medical record system and personal digital assistants to assess and follow patients with respiratory infections visiting a rural Kenyan health center. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2006;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odero W, Rotich J, Yiannoutsos CT, Ouna T, Tierney WM. Innovative approaches to application of information technology in disease surveillance and prevention in western Kenya. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odero W, Polsky S, Urbane D, Carel R, Tierney WM. Characteristics of injuries presenting to a rural health centre in western Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:367–73. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i8.9543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einterz RM, Kimaiyo S, Mengech HNK, Khwa-Otsyula BO, Esamai F, Quigley F, Mamlin JJ. Responding to the HIV pandemic: The power of an academic medical partnership. Acad Med. 2007;82:812–818. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180cc29f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inui TS, Nyandiko WM, Kimaiyo SN, Frankel RM, Muriuki T, Mamlin JJ, Einterz RM, Sidle JE. AMPATH: Living proof that no one has to die from HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;21:1745–1750. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0437-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitka M. MTCT-Plus program has two goals: End maternal HIV transmission + treat mothers. JAMA. 2002;288:153–154. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J. The president’s emergency plan for AIDS relief in Africa: An evaluation of outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:688–695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siika AM, Rotich JK, Simiyu CJ, Kigotho EM, Smith FE, Sidle JE, Wools-Kaloustian K, Kimaiyo SN, Nyandiko WN, Hannan TJ, Tierney WM. An electronic medical record system for ambulatory care of HIV-infected patients in Kenya. Int J Med Informat. 2005;74:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sidle JE, Were E, Wools-Kaloustian K, Chuani C, Salmon K, Tierney WM, Meslin EM. A needs assessment to build international research ethics capacity. J Empiric Res Human Res Ethics. 2006;1:23–38. doi: 10.1525/jer.2006.1.2.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer D, Yebei V, Kimaiyo S, et al. Equitable treatment for HIV/AIDS clinical trial participants: A focus group study of patients, clinician-researchers, and administrators in western Kenya. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:55–60. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kho AN, Zafar A, Tierney WM. Electronic data collection in practice-based research networks: Lessons learned from a successful implementation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:196–203. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.02.060114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institutes of Health. International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS. Available at: http://www.iedea.org/, accessed February 17, 2013.

- 24.Green SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health care system: From concept to action. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:207–211. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Ethical Considerations in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Authorship and Contributorship. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html, accessed February 17, 2013.

- 26.Tierney WM, Kanter AS, Fraser HSF, Bailey C. A toolkit for e-health partnerships in low-income nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:272–277. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office of Management and Budget. Circular A-21: Cost principles to educational institutions (Revised 05/10/04). Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a021_2004, accessed February 17, 2013.