ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Although prior randomized trials have demonstrated that procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy effectively reduces antibiotic use in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), uncertainties remain regarding use of procalcitonin protocols in practice.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of procalcitonin protocols in CAP.

DESIGN

Decision analysis using published observational and clinical trial data, with variation of all parameter values in sensitivity analyses.

PATIENTS

Hypothetical patient cohorts who were hospitalized for CAP.

INTERVENTIONS

Procalcitonin protocols vs. usual care.

MAIN MEASURES

Costs and cost per quality adjusted life year gained.

KEY RESULTS

When no differences in clinical outcomes were assumed, consistent with clinical trials and observational data, procalcitonin protocols cost $10–$54 more per patient than usual care in CAP patients. Under these assumptions, results were most sensitive to variations in: antibiotic cost, the likelihood that antibiotic therapy was initiated less frequently or over shorter durations, and the likelihood that physicians were nonadherent to procalcitonin protocols. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses, incorporating procalcitonin protocol-related changes in quality of life, found that protocol use was unlikely to be economically reasonable if physician protocol nonadherence was high, as observational study data suggest. However, procalcitonin protocols were favored if they decreased hospital length of stay.

CONCLUSIONS

Procalcitonin protocol use in hospitalized CAP patients, although promising, lacks physician nonadherence and resource use data in routine care settings, which are needed to evaluate its potential role in patient care.

KEY WORDS: cost-effectiveness analysis, procalcitonin, community-acquired pneumonia

According to Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA)/ American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) treatment, antibiotic therapy “should be administered as soon as possible after the diagnosis is considered likely,” and directed as narrowly as possible to the causative pathogen to limit antibiotic resistance.1 However, determining CAP etiology is often difficult and, in most cases, antibiotic therapy is empiric, since traditional pathogen testing is neither accurate nor rapid enough to assist in real-time antibiotic decision-making.1–3 In addition, the optimal antibiotic therapy duration and route (intravenous vs. oral) for CAP are unclear.1 Despite evidence-based guidelines, clinicians’ antibiotic therapy decisions favor overtreatment, with antibiotics frequently prescribed for nonbacterial illness or for longer than necessary to successfully treat infection, heightening antibiotic resistance risk and increasing medical care costs.4,5

Rapid testing to detect bacterial and viral antigens could be a solution to the antibiotic prescription dilemma in CAP, but poor sensitivity has, to date, minimized usefulness.1 Rapidly available biomarker tests, such as procalcitonin, show greater promise. Randomized trials suggest that procalcitonin protocols reduce antibiotic use in lower respiratory infections with unchanged clinical outcomes.6 Elevated serum procalcitonin levels are associated with bacterial infection when nonbacterial infection or noninfectious disease might also be considered.7,8 In addition, studies suggest that significant decreases in procalcitonin levels in antibiotic-treated infections indicate treatment success, and can be used as a criterion for discontinuing antibiotic therapy.6

Procalcitonin testing in CAP might seem logical, given uncertainty in etiologic diagnosis and favorable clinical trial outcomes. However, several uncertainties regarding procalcitonin testing remain. First, the risk of inappropriately omitting antibiotic therapy while following procalcitonin protocols could be diluted in clinical trials where all lower respiratory tract infections were considered together.6 Second, physicians commonly start or continue antibiotics when procalcitonin levels suggest they should not.9 A recent study suggested that appropriate procalcitonin use in the US could be hampered by physician unfamiliarity with the test, raising the possibility that procalcitonin protocol implementation issues, including physician training, could have major effects on its impact.9 Third, it is unclear how procalcitonin protocol use might change hospital length of stay and other drivers of medical resource use in the US, given secular trends toward shorter hospitalizations.10 Finally, the cost implications of procalcitonin testing are unknown. With these questions in mind, we used cost-effectiveness analysis techniques to explore circumstances where implementation of procalcitonin testing in CAP would be favorable, and where further research to resolve uncertainty is needed.

METHODS

We used a decision model examining hypothetical patient cohorts to estimate the cost-effectiveness of procalcitonin protocols compared to usual care in patients hospitalized for CAP. We took a third-party payer perspective, with costs in 2011 US$, inflated as necessary using the US Consumer Price Index.11 The model time horizon was the duration of the hospital stay.

We examined two procalcitonin protocols studied in clinical trials for low-risk patients hospitalized with CAP and one protocol in high-risk hospitalized patients. Low-risk CAP was defined in procalcitonin studies as a Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) risk class of ≤ 3, or a CURB-65 score of ≤ 2; high-risk CAP was PSI risk classes 4 or 5, or CURB-65 scores of ≥ 3.12,13 In low-risk patients, one protocol measured procalcitonin only on admission, which can only guide antibiotic initiation decisions.6 The second protocol in low-risk patients measured procalcitonin on admission and on days 3, 5, and 7 if patients were still hospitalized at those points, guiding both antibiotic initiation and duration decisions.9 Procalcitonin is measured in the same fashion in high-risk patients; however, antibiotic is initiated regardless of procalcitonin levels, and protocols exclusively guide antibiotic therapy duration.9

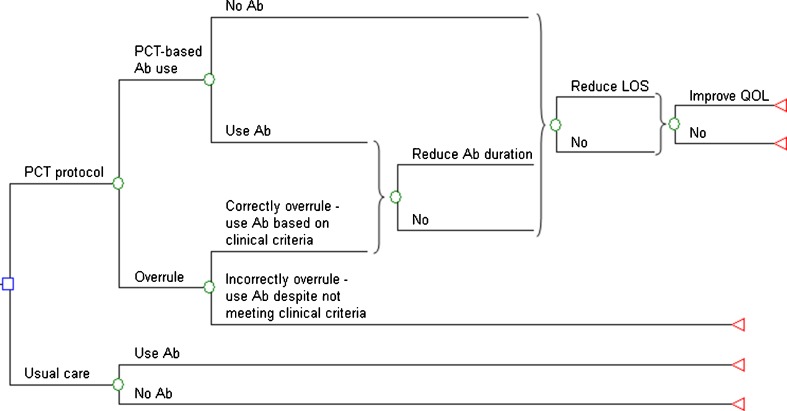

Figure 1 depicts the decision analysis model for low-risk hospitalized patients with CAP; the decision is whether to obtain procalcitonin levels to guide antibiotic therapy or to treat CAP as usual without procalcitonin protocol guidance. If procalcitonin levels are obtained, physicians can follow protocol recommendations, either basing antibiotic treatment decisions on procalcitonin levels, or treating with antibiotics based on the protocol’s clinical criteria. Alternatively, they can incorrectly overrule recommendations, initiating antibiotic therapy when procalcitonin levels are low and clinical criteria for antibiotic use are not met. Procalcitonin protocol clinical criteria for initiating antibiotic therapy are: 1) ICU or monitored unit admission for respiratory or hemodynamic stability; 2) life-threatening comorbidity (imminent death, severe immunosuppression, or chronic infection requiring antibiotics); and 3) infectious complications and difficult to treat organisms (e.g., abscess, empyema, legionella infection). Thus, physicians correctly following procalcitonin protocols can begin antibiotic treatment based either on procalcitonin levels or on protocol clinical criteria. When the protocol is incorrectly overruled, we assume that procalcitonin levels are obtained, but antibiotic therapy initiation and duration are unchanged from usual care. We assume that physicians will not err through not initiating antibiotic when procalcitonin levels are high.

Figure 1.

Procalcitonin protocol decision tree for low-risk pneumonia. Legend: The tree diagram depicts the decision to use or not use a procalcitonin protocol in low-risk hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Ab = antibiotic, QOL = quality of life.

In the base case, we assume no differences in hospital length of stay, hospitalization costs, or quality of life between procalcitonin protocol use and nonuse strategies; however, we examined these possibilities in separate sensitivity analyses. Thus, the only differences between strategies were in antibiotic use and antibiotic costs, with all other costs being equal between strategies, perhaps biasing against procalcitonin use. We used a similar model in high-risk patients, except that antibiotics are initiated in all patients and the procalcitonin protocol only guides antibiotic duration. Published procalcitonin protocols recommend repeat procalcitonin levels within 6 to 24 h after a negative test; in the base case analysis, we omit repeat testing, potentially biasing the analysis toward procalcitonin protocol use; however, we examine the effect of repeat testing in a sensitivity analysis.

In randomized clinical trials, procalcitonin protocols decreased the absolute probability of antibiotic initiation (mean 9.9 %) and the duration of therapy (mean 4.5 days) compared to usual care in CAP.6 A meta-analysis of those trials found no increase in mortality or adverse events between patients managed using a procalcitonin protocol and usual care; however, many studies included in the meta-analysis were of limited quality.6 More recently, an international observational study of procalcitonin protocol use showed that antibiotic duration was 1.51 days less when physicians complied with procalcitonin algorithm recommendations compared to protocol nonadherence, but that protocol adherence was only 68.2 % overall, with < 40 % adherence observed in the single US center included in the study.9 Once again, compared to usual care, no differences in mortality or adverse events were associated with procalcitonin protocol use in this study.

Base case values and parameter ranges examined in sensitivity analyses are shown in Table 1. In the model, low-risk adults hospitalized with CAP had a median length of stay of 4 days, based on Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP) data on Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) 194 (simple pneumonia and pleurisy with comorbid condition).14 We used DRG 193 (simple pneumonia and pleurisy with major comorbid condition) as for high-risk CAP, with a median length of stay of 5 days.14 To adjust the observation study-based decreases in antibiotic duration to these DRG-related time intervals, we multiplied observed changes in antibiotic duration by the quotient of DRG length of stay and study-based length of observation, then varied this value in sensitivity analyses. This method assumes that antibiotic use is similar in usual care and when procalcitonin protocol nonadherence occurred. We calculated that, with adherence to procalcitonin protocols, antibiotics were used for 0.82 fewer days in patients hospitalized with low-risk CAP and 1.02 fewer days in the high-risk group. In sensitivity analyses, we examined greater decreases in duration of antibiotic therapy consistent with those observed in randomized trials.

Table 1.

Parameter Values Used in the Model and Ranges Examined In Sensitivity Analyses

| Parameter | Value | Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilities | |||

| Antibiotic initiation in low-risk pneumonia | |||

| Without procalcitonin protocol | 99.0 % | 97–100 % | 6 |

| With procalcitonin protocol | 89.1 % | 85–91 % | 6 |

| Antibiotic initiation in high-risk pneumonia | 100 % | NA | 9 |

| Correctly provide antibiotic based on clinical criteria | 17.2 % | 14.9–19.7 % | 9 |

| Protocol nonadherence* | 36.3 % | 10–70 % | 9 |

| Durations | |||

| In hospital antibiotic (days, median) | |||

| Without procalcitonin protocol | |||

| Low-risk patients | 4 | 1.9–8.4 | 14 |

| High-risk patients | 5 | 1.4–18.0 | 14 |

| Decreased hospital antibiotic use with procalcitonin protocol (days) | Calculated from9 | ||

| Low-risk patients | 0.82 | 0.54–5.0 | |

| High-risk patients | 1.02 | 0.67–5.0 | |

| Costs | |||

| Procalcitonin testing (per test) | $38.36 | $30–$47 | 15 |

| Daily antibiotic and intravenous therapy | $102 | $74–$150 | 16 |

| Projected savings from reducing hospital stay by 1 day | $1,032 | $935–$1,557 | 16 |

*Derived from patients with CAP (343 [incorrectly overruled]/945 [total]) in the cited reference

Medicare reimbursement for procalcitonin is $38.36.15 Daily antibiotic and intravenous solution costs ($102) and the cost reduction from decreasing hospital length of stay by 1 day ($1,032) were obtained from the medical literature and inflated to 2011 US$.16

Because physician adherence with procalcitonin protocols has been highly variable in published studies and could be a major determinant of protocol cost-effectiveness, we examined a scenario where protocol nonadherence was high (60 %, range 50–70 %), designed to mirror observed US physician nonadherence.9 We also examined scenarios where both quality of life and hospital length of stay differed between procalcitonin protocol use and usual care. When examining possible quality of life differences, we assumed that the quality of life utility weight of hospitalization was 0.2 less (range 0.1–0.4) compared to not being hospitalized (on a 0 to 1 scale).17 Thus, the disutility of a hospital day was −0.2 quality adjusted days or −0.00055 (range -0.00027 to −0.0011) quality adjusted life years (QALYs). Smaller utility differences between home and hospital utility have been observed in CAP patients18; we used the larger values to bias toward procalcitonin use. In addition, we examined the possibility of quality of life loss due to procalcitonin protocol use, using 4.8 % for this probability, based on the adjusted odds ratio for hospital mortality (1.048, p = 0.95) in the international observational study.9 In the model, use of this factor decreased the quality of life advantage of procalcitonin protocol use by 4.8 %.

All parameters listed in Table 1 were varied individually over their listed ranges in one-way sensitivity analyses and simultaneously over distributions 10,000 times in a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. One-way sensitivity analyses and three-way sensitivity analyses of selected parameters concentrated on the base case scenario, where no differences in clinical outcomes occurred. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses examined scenarios where differences in quality of life, hospital length of stay, and hospitalization costs could occur.

RESULTS

In the base case scenario, where no differences in clinical outcomes or hospital length of stay were assumed, a strategy of obtaining procalcitonin levels only on admission of low-risk patients and using them to guide antibiotic initiation cost $22 more than usual care. In this same group, using procalcitonin levels at admission and every second day thereafter while hospitalized to guide both antibiotic initiation and duration of therapy, cost $10 more than usual care. In high-risk patients, where antibiotic was routinely initiated, using procalcitonin levels to guide duration of therapy cost $54 more than usual care.

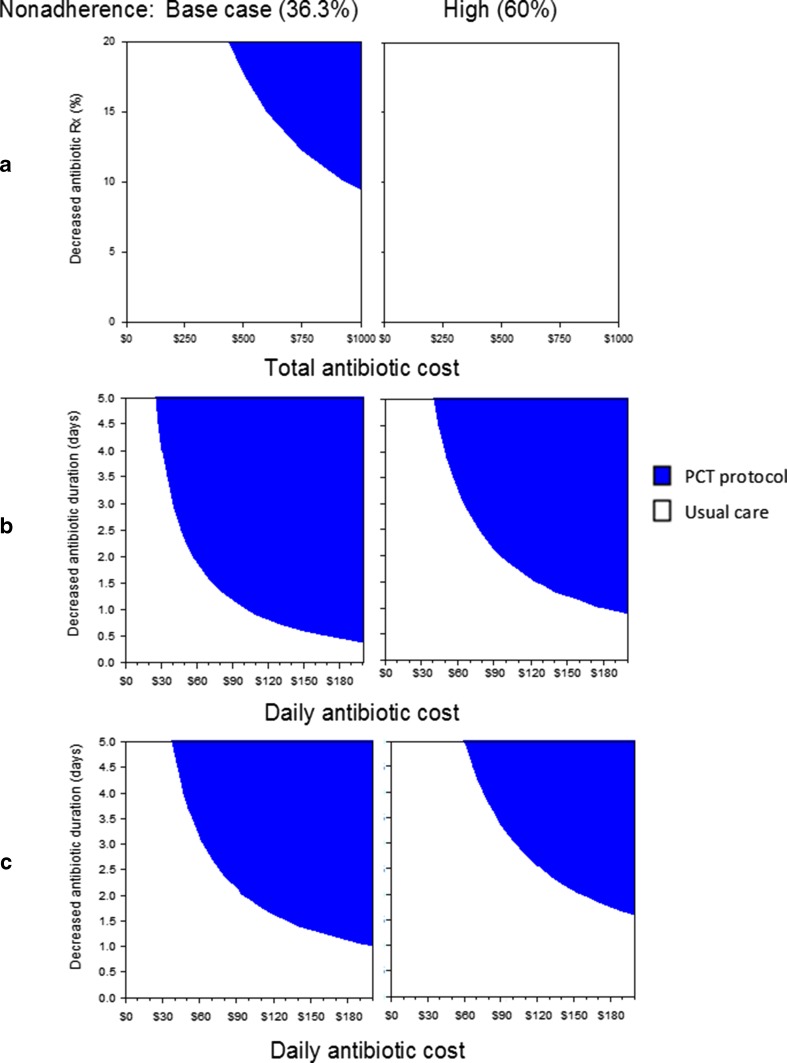

In one-way sensitivity analyses under base case assumptions and in all procalcitonin protocol scenarios, results were most sensitive to variation of: antibiotic costs, the likelihood that antibiotic therapy was initiated less frequently or over shorter durations, and the likelihood that physicians were nonadherent to procalcitonin protocols. The effects of simultaneously varying these values are shown in Fig. 2. In a sensitivity analysis of the first scenario, low-risk patients with procalcitonin drawn only on admission (Fig. 2, top panels), the procalcitonin protocol costs less than usual care when total antibiotic costs are varied to ≥ $944 (base case = $407) and base case values are maintained for the absolute decrease in antibiotic initiation (9.9 %) and for physician protocol nonadherence (36.3 %) (Fig. 2, top left panel). However, when nonadherence is high (60 %), procalcitonin protocol use is never less expensive than usual care (top right panel).

Figure 2.

Three-way sensitivity analysis. Graphs depict areas where strategies are favored in the base case analysis when no differences in patient outcomes or hospital length of stay are assumed. Points for parameters on the x- and y-axes that fall within shaded areas depict where procalcitonin protocol use is cost saving compared to usual care. Graphs in row a show results when procalcitonin levels are only drawn on admission in low-risk patients, row b depicts when procalcitonin levels are drawn on admission and every second day thereafter in low-risk patients, and row c shows procalcitonin protocol use in high-risk patients. Columns depict scenarios where physician nonadherence is held at base case levels (36.3 %) or at high levels (60 %). Rx = prescription, PCT = procalcitonin.

In the other two scenarios, where protocol use can decrease antibiotic duration, daily antibiotic cost and decreased antibiotic duration are the parameters of interest. In low-risk patients (Fig. 2, middle panels), using base case values for physician protocol nonadherence and daily antibiotic/intravenous therapy costs ($102), procalcitonin protocols cost less than usual care when antibiotic duration is decreased ≥ 0.98 days (base case = 0.82 days); however, when protocol nonadherence is high, duration must decrease ≥ 1.83 days. In high-risk patients (Fig. 2, bottom panels), where the base case decrease in antibiotic duration is 1.02 days, procalcitonin protocol use is cost saving when antibiotic duration is decreased ≥ 1.86 days or ≥ 2.96 days when protocol nonadherence is at base case or high levels, respectively. Adding a second confirmatory procalcitonin level after a negative test on admission had little impact on results.

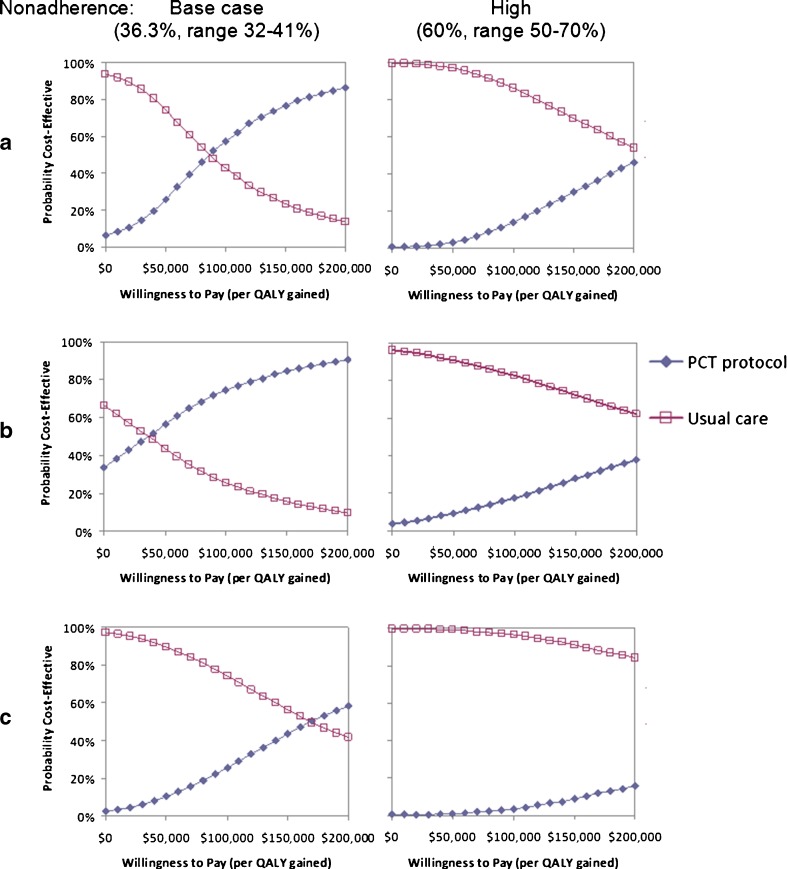

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses incorporating the possibility of quality of life effects (including mortality) due to procalcitonin protocol use are shown as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (Fig. 3), depicting the likelihood that interventions would be considered cost-effective over a range of willingness-to-pay (or acceptability) thresholds. In low-risk patients under base case ranges for physician protocol nonadherence (incorrectly overruling the protocol 32–41 % of the time), procalcitonin protocol use was favored when the willingness-to-pay threshold was ≥ $90,000 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained (when a single procalcitonin level is obtained) or ≥ $40,000/QALY gained (when repeated procalcitonin levels are performed). In high-risk patients, a procalcitonin protocol was favored only when thresholds were ≥ $170,000/QALY.

Figure 3.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves show the likelihood that strategies will be favored over ranges of willingness to pay (or acceptability) thresholds. These analyses include the possibility of positive or negative impact on quality of life through procalcitonin protocol use. In row a, procalcitonin levels are only drawn on admission in low-risk patients; in b, procalcitonin levels are drawn on admission and every second day thereafter in low-risk patients; and c depicts procalcitonin protocol use in high-risk patients.

In all the previously described analyses, no differences in hospitalization duration or costs were assumed between strategies, except for costs related to procalcitonin testing and antibiotics. Incorporating the possibility of decreasing hospital length of stay and its corresponding costs strongly favored procalcitonin protocols, where they cost less and were more effective than usual care. In all scenarios, procalcitonin protocols were favored if hospital costs were decreased ≥ $175, corresponding to decreased length of stay ≥ 0.17 days (range 0.11–0.19 days).

DISCUSSION

In this cost-effectiveness analysis of a procalcitonin-based algorithm to guide antibiotic therapy in patients hospitalized with CAP, procalcitonin use favorability depended most strongly on practitioner adherence to protocol recommendations and the likelihood that protocol use resulted in decreased length of hospital stay. Less influential was the clinical situation in which it was used. In low-risk patients with CAP, a single test on admission to guide antibiotic use decisions was less favored than repeated testing to guide both antibiotic initiation and duration; protocol use in high-risk patients was least favored in the base case scenario. However, in any clinical situation, low adherence to a procalcitonin algorithm made its use unfavorable and, conversely, the possibility of decreased hospital length of stay and lower hospitalization costs due to the procalcitonin protocol strongly favored its use.

Our analysis suggests that, as with many new interventions, the impact of procalcitonin use in hospitalized patients with CAP depends largely on how it is implemented.19,20 Physicians are often skeptical of new testing procedures; is this uncertainty with procalcitonin protocol use warranted? Randomized trials favoring procalcitonin protocols were performed in only a few non-US hospitals, and those studies’ generalizability is unclear.6,21 More recently, in a single-center randomized controlled trial of ICU patients in Belgium, antibiotic consumption was not reduced and test sensitivity and specificity were suboptimal in differentiating confirmed and probable infection from possible and no infection, with an ROC curve area of 0.69.22 Similar studies, preferably multicenter and international, should be performed to examine procalcitonin protocol use in CAP patients.

In the US, hospital length of stay for pneumonia is relatively short, typically 3 to 5 days, often following evidence-based guidelines for switching from IV to oral antibiotics and determining clinical stability for hospital discharge.23–25 This raises the question whether hospitalization is the proper context to be considered in our analysis. If this is the proper consideration, then the question is whether procalcitonin protocol use can further shorten length of stay. If it is not the appropriate context, then it is not clear if cost savings could occur with procalcitonin protocol use after hospital discharge, since discharged patients typically continue on less expensive oral antibiotic therapy. Procalcitonin testing could cost more than the possible antibiotic cost savings in this scenario.

Antibiotic stewardship is another reason to consider procalcitonin testing, decreasing antibiotic resistance through decreased antibiotic use. However, antibiotic use in CAP may not have much impact in this regard. CAP is relatively uncommon, and has a relatively high likelihood of having a bacterial cause compared to upper respiratory infections and acute bronchitis, where inappropriate antibiotic use for nonbacterial etiologies is common. If procalcitonin testing is shown, in a generalizable way, to diminish antibiotic use in these illnesses, then it should have greater impact on antibiotic resistance levels and better fulfill antibiotic stewardship goals. Procalcitonin protocols might also be more valuable when there is a low pretest probability of bacterial infection, and conversely, have lesser value in CAP, particularly if protocols lack sensitivity and lead to many false negative tests.

Procalcitonin testing might be more favorable in CAP patients who are expected to have longer hospital stays and longer courses of more expensive antibiotics, e.g., CAP patients admitted to ICUs. However, further evidence is needed to support this contention. In the previously mentioned study of ICU patients,22 no advantage was seen with procalcitonin protocol use, while a systematic review of studies in ICU patients suggested some advantages to its use.21

Available randomized trials of procalcitonin protocols in CAP patients lack comparisons with the use of other evidence-based guidelines.26–29 It is unclear whether these guidelines were followed in procalcitonin protocol trials’ control groups, but future studies should consider adding trial arms where these comparisons could occur. In addition, trials of varying antibiotic duration have shown, in many cases, that shorter antibiotic duration in CAP can be considered.30 Future trials should also consider these strategies. Decreased costs, decreased hospital length of stay, and better antibiotic stewardship in CAP patients could result from procalcitonin protocol use, but more research is needed to evaluate these possibilities.

Decision analysis techniques, using mathematical models, are limited by the data available to populate them, but can be useful in illustrating the uncertainty surrounding clinical choices and pointing out where additional research would be most valuable to reduce that uncertainty. Future research on procalcitonin protocol use, based on our analysis, should assess interventions to improve procalcitonin protocol adherence in a wider spectrum of healthcare settings, and capture the effects of protocol use on resource utilization and patient outcomes. This research would be enhanced if more direct comparisons with other evidence-based CAP management protocols were also performed.

We conclude that procalcitonin protocol use in hospitalized patients with CAP, although promising, lacks the data necessary to fully evaluate its role in patient care. Available studies show procalcitonin protocol efficacy, but do not highlight the importance of how protocols might be implemented and ultimately followed by clinicians, or how medical care and resource use might change if they are used. Further research is needed to allow evidence-based decisions regarding procalcitonin protocol use to be made.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Supported by the NIAID (R01AI 076256)

Prior presentations

Presented in part at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Zimmerman and Dr. Nowalk have a research grant from Merck to study the HPV vaccine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Vazquez E, Marcos MA, Mensa J, et al. Assessment of the usefulness of sputum culture for diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia using the PORT predictive scoring system. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1807–11. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed WW, Byrd GS, Gates RH, Jr, Howard RS, Weaver MJ. Sputum gram’s stain in community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. A meta-analysis. West J Med. 1996;165:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacconelli E. Antimicrobial use: risk driver of multidrug resistant microorganisms in healthcare settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:352–8. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832d52e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Managing antibiotic resistance. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1961–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuetz P, Chiappa V, Briel M, Greenwald JL. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1322–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker KL, Nylen ES, White JC, Muller B, Snider RH., Jr Procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1512–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller F, Christ-Crain M, Bregenzer T, et al. Procalcitonin levels predict bacteremia in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort trial. Chest. 2010;138:121–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.10954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrich WC, Dusemund F, Bucher B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy in lower respiratory tract infections in “Real Life”: an International, Multicenter Poststudy Survey (ProREAL) Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:715–22. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yealy DM, Fine MJ. Measurement of serum procalcitonin: a step closer to tailored care for respiratory infections? JAMA. 2009;302:1115–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/#data (Accessed February 19, 2013)

- 12.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377–82. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry AM, Zell ER, Schuchat A, Butler JC, Whitney CG. Comparing potential benefits of new pneumococcal vaccines with the current polysaccharide vaccine in the elderly. Vaccine. 2002;21:303–11. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. New Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Test Codes. Procalcitonin. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Downloads/CY2011-CLFS-New-Test-Codes.pdf. (Accessed February 19, 2013)

- 16.Fine MJ, Pratt HM, Obrosky DS, et al. Relation between length of hospital stay and costs of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2000;109:378–85. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold MR, Franks P, McCoy KI, Fryback DG. Toward consistency in cost-utility analyses: using national measures to create condition-specific values. Med Care. 1998;36:778–92. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coley CM, Li YH, Medsger AR, et al. Preferences for home vs hospital care among low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1565–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440130115012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharpe BA. Putting a critical pathway into practice: the devil is in the implementation details: comment on “effect of a 3-step critical pathway to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay in community-acquired pneumonia”putting a critical pathway into practice. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:928–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal R, Schwartz DN. Procalcitonin to guide duration of antimicrobial therapy in intensive care units: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:379–87. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Layios N, Lambermont B, Canivet JL, et al. Procalcitonin usefulness for the initiation of antibiotic treatment in intensive care unit patients*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2304–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318251517a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine MJ, Medsger AR, Stone RA, et al. The hospital discharge decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:47–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440220051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine MJ, Stone RA, Lave JR, et al. Implementation of an evidence-based guideline to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2003;115:343–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine MJ, Stone RA, Singer DE, et al. Processes and outcomes of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:970–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carratala J, Garcia-Vidal C, Ortega L, et al. Effect of a 3-step critical pathway to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trialA 3-step critical pathway for CAP. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:922–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnoor M, Meyer T, Suttorp N, Raspe H, Welte T, Schafer T. Development and evaluation of an implementation strategy for the German guideline on community-acquired pneumonia. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:498–502. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mundy LM, Leet TL, Darst K, Schnitzler MA, Dunagan WC. Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;124:883–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhew DC, Tu GS, Ofman J, Henning JM, Richards MS, Weingarten SR. Early switch and early discharge strategies in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:722–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120:783–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]