Abstract

BACKGROUND

Trauma and hypovolemic shock are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and septic complications. We hypothesize that hypovolemic shock and resuscitation results in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) mitochondrial dysfunction that is linked to immunosuppression.

METHODS

Using a decompensated shock model, Long-Evans rats were bled to a MAP of 40 mmHg until the blood pressure could no longer be maintained without fluid infusion. Shock was sustained by incremental infusion of Lactated Ringer’s solution (LR) until 40% of the shed volume had been returned (severe shock). Animals were resuscitated with 4X the shed volume in LR over 60 minutes (resuscitation). Control animals underwent line placement, but were not hemorrhaged. Animals were randomized to control (n=5), severe shock (n=5), or resuscitation (n=6) groups. At each time point, PBMC were isolated for mitochondrial function analysis using flow cytometry and high resolution respirometry. Immune function was evaluated by quantifying serum IL-6 and TNF-α after PBMC stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The impact of plasma on mitochondrial function was evaluated by incubating PBMC’s harvested following severe shock with control plasma. PBMC’s from control animals were likewise mixed with plasma collected following resuscitation. Student’s t-test and Pearson correlations were performed (significance: p <0.05).

RESULTS

Following resuscitation, PBMCs demonstrated significant bioenergetic failure with a marked decrease in basal, maximal, and ATP-linked respiration. Mitochondrial membrane potential also decreased significantly by 50% following resuscitation. Serum IL6 increased, while LPS stimulated TNF-α production decreased dramatically following shock and resuscitation. Observed mitochondrial dysfunction correlated significantly with IL6 and TNF-α levels. PBMCs demonstrated significant mitochondrial recovery when incubated in control serum, whereas control PBMCs developed depressed function when incubated with serum collected following severe shock.

CONCLUSION

Mitochondrial dysfunction following hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation was associated with the inhibition of PBMC response to endotoxin that may lead to an immunosuppressed state.

Keywords: Hemorrhagic shock, Long-Evans rats, peripheral blood mononuclear cell, mitochondrial function, membrane potential, immune function

Background

Despite advances in critical care, infectious complications following traumatic injury remain a significant source of morbidity and mortality.(1) In a retrospective study of over 30,000 trauma patients, Osborn et al noted sepsis not only significantly increased the need for ICU and hospital days, it substantially increased the mortality rate from 7.6% to 23.1%.(2) In a similar study using Nationwide Inpatient Sampled Data, trauma patients who developed sepsis had a nearly 6-fold higher risk of dying when compared to patients who did not develop an infection. Moreover, the cost of caring for septic trauma patients was more than double that of non-infected patients.(3) Clearly, a better understanding of the pathophysiology leading to post-traumatic sepsis could have enormous therapeutic and financial consequences.

The first-line of defense against foreign pathogens and other danger-associated molecular proteins following injury is provided by the innate immune system.(4,5) This coordinated system of immune cells, cytokines and complement provides an immediate, non-specific response that limits the spread of infection while activating a long-term, adaptive response.(4,6) Monocytes and their mature phagocytic phenotype, macrophages, are critical in this early protective response.(6) Following significant trauma, however, the robust pro-inflammatory response is frequently replaced by a marked state of immunosuppression with altered cytokine release and decreased microbicidal activity.(7–10) Importantly, prolonged impairment of monocyte function and decreased antigen-presenting capacity have been associated with the development of septic complications. (11–14)

Although the mechanisms underlying post-traumatic immunosuppression are not completely understood, impaired mitochondrial function may play a pivotal role. Activating the immune response is a highly energetic process and decreased PBMC mitochondrial function may be associated with an impaired capacity to respond appropriately to pathogens ex vivo (15–17). Moreover, in critically ill patients, decreased mitochondrial oxygen consumption in PBMCs may modulate the severity of sepsis (15–18). Severely injured patients may also be at risk for mitochondrial dysfunction despite adequate resuscitation (19–21). We hypothesized that hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation result in PBMC mitochondrial dysfunction that contributes to the development of post-traumatic immune suppression.

Methods

Experimental Protocol

Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania and were performed in adherence to the NIH Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Long-Evans rats (250–300 grams) were housed in a facility with constant temperature and humidity with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Animals were allowed to acclimate at least 2 days prior to surgery and given access to food and water ad libitum. Using a well validated decompensated hemorrhagic shock model (22), animals were randomized to one of three experimental groups: control (n=5), severe shock (n=6), or resuscitation (n=6). All animals were anesthetized using vaporized isofluorane (3.5%) and underwent placement of vascular catheters (PE50, Braintree Scientific, Inc., Braintree, Massachusettes). A laparotomy (5cm) was performed to simulate soft tissue injury and surgically closed. Animals were allowed to emerge from anesthesia. Once stable (~ 30 minutes), animals were passively bled via the femoral artery to a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 40 mmHg. When a MAP of 40 mmHg could no longer be maintained secondary to vascular decompensation, incremental boluses (0.2 cc) of lactated Ringer’s (LR) were given to maintain the MAP at 40 mmHg. Animals were considered to be in severe shock when 40% of the shed volume had been returned by small boluses. Animals were subsequently resuscitated with 4X the total shed volume in LR over 60 minutes (Resuscitation).(23) This model results in class IV hemorrhagic shock and is associated with a 70% mortality rate at 7 days.(24) Prior to sacrifice, blood samples were taken and assayed for TNF-α, IL-6, arterial blood gases, lactate, hemoglobin, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and electrolytes (i-STAT, Abbot Point of Care Inc., Princeton, NJ). Samples were also taken for PBMC isolation. Animals were subsequently humanely euthanized.

PBMC Isolation

Under sterile conditions, blood samples were diluted 1:1 using a balanced salt solution (BSS: 1 volume of anhydrous D-glucose 0.1 %, CaCl2 50 uM, MgCl2 0.98 mM, KCl 5.4 mM, TRIS 145 mM and 9 volumes of NaCl 140 mM). Diluted blood samples (2–4 mL) were layered on top of 3 mL Ficoll-Paque™ PREMIUM 1.084 (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) and centrifuged at 400 x g for 40 minutes (18 – 20 °C). The white buffy coat was gently aspirated, mixed with 3 to 4 volumes of BSS, and recentrifuged at 400 x g for 15 minutes. The PBMC pellet was washed in 6–8 mL BSS and centrifuged at 400 x g for 10 minutes. The final PBMC pellet was resuspended in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for flow cytometry or in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (pH 7.4) containing 5.5 mM glucose and 1 mM pyruvate. Cell count and viability were performed using trypan blue exclusion (Countess, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and ranged between 90 and 97%.

Flow Cytometry Assessment of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Reactive Oxygen Species

Freshly isolated PBMCs were stained with tetramethylrhodamine (TMRE) to assess membrane potential (ΔΨm), Mitosox Red to measure production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and MitoTracker Green to determine mitochondrial content (Life Technologies, New York, NY). In order to normalize to mitochondrial content, two-color fluorophore experiments were performed by incubating PBMCs (106 – 108 cells/mL) in the dark at 37 °C with MitoTracker Green (140 nM x 45 min) and either TMRE (75 nM x 30 min) or Mitosox Red (5mM x 15 min). PBMCs were then washed twice with PBS. Positive and compensation controls were established for each dye. Mitosox Red and TMRE were then excited with a green laser with 660/20 and 585/42 filters respectively. For assessing MitoTracker Green, a blue laser with a 515/20 filter was used. PBMCs were identified using Forward (FSC) and Side (SSC) scatter. Only cells that stained positive for MitoTracker Green, and thus viable, were considered. Data acquisition was performed using DiVa 6.1.2 software (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and 100,000 events were recorded per tube. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, Oregon).

Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption

Measurements of mitochondrial oxygen consumption were performed using a high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2k Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). Freshly isolated non-permeabilized PBMCs (106 cells/mL) were resuspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, 37°C) containing 5.5 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The oxygen solubility factor was set to 0.92 (relative to pure water) for the HBSS-glucose-pyruvate solution.

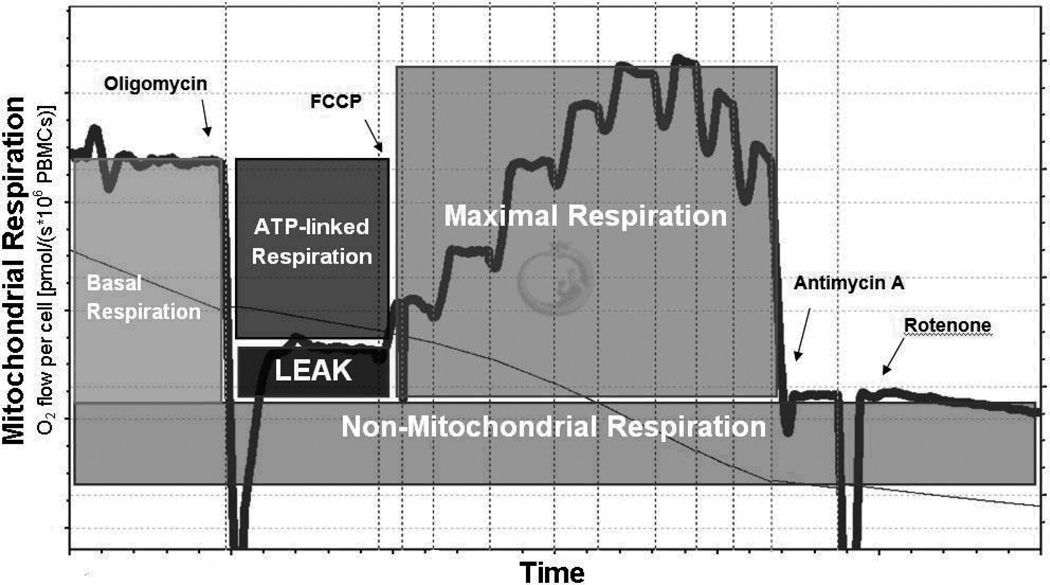

After PBMC stabilization (3–5 minutes), real-time oxygen concentration and flux data were collected continuously (DatLab software 4.3, Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). After the basal respiration rate was recorded, oligomycin (0.25 µg/ml), a mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitor, was added to measure respiration independent of ATP production (proton leak). The maximal capacity of the electron transport system (i.e. maximal respiratory rate) was assessed by titrating the protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 0.75 µM increments) until no further increase in oxygen consumption was detected. We assessed non-mitochondrial respiration by inhibiting the respiratory chain with rotenone (complex I inhibitor, 0.5 µM) and antimycin-A (complex III inhibitor, 2.5 µM). Using these data, the mitochondrial reserve capacity and the ATP-linked respiration were calculated (Figure 1).(25–27)

Figure 1. Bioenergetic profile of PBMC.

Representative trace of the substrate-inhibitor protocol used to evaluate the mitochondrial oxygen consumption in PBMC using high resolution respirometry. After measuring the Basal Respiration, Oligomycin, an ATP-synthase inhibitor, is added to obtain the Leak and ATP-linked respiration (Basal Respiration minus Leak Respiration). In order to obtain the Maximal Respiration, the protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone (FCCP) is repeatedly added until the maximal oxygen consumption is reached. Finally, the residual respiration is obtained by inhibiting both mitochondrial complex III using Antimycin A and complex I using rotenone.

In order to determine whether any observed mitochondrial dysfunction was an irreversible phenomenon secondary to shock or a reversible defect resulting from plasma factors, a crossover experiment was performed. PBMCs harvested from control animals were incubated in plasma collected from animals at the end of resuscitation. Similarly, PBMCs isolated from animals at the end of resuscitation were mixed with control plasma.(17) At the end of the 3 hour incubation period, PBMC oxygen consumption was assessed using high resolution respirometry as previously described.

TNF-α Production and Serum IL-6 Levels

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 purified by ion-exchange chromatography was freshly prepared (200 µg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich Co. St. Louis, MO). Using sterile polypropylene tubes, 100 µL of LPS was mixed with 200 µL of rat whole blood and 300 µL of sterile saline at each time point. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Following centrifugation at 3000 x g for 1 min, cell-free supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. Whole rat blood (200 µL) without LPS was incubated with sterile saline under identical conditions to determine basal levels of TNF-α. In order to measure serum IL-6 levels, 200 µL of rat whole blood was centrifuged at 3000 x g for 1 minute and plasma was stored at −80°C.

Using commercially available ELISA assay kits, TNF-α and IL-6 were measured post hoc (Life technologies, New York). In brief, 50 µL of assay diluents and 50 µL of supernatant were pipetted into wells precoated with the specific antibody for either rat TNF-α or IL-6. Following a 2-hour incubation at room temperature, an enzyme-linked antibody specific for rat TNF-α or IL-6 was added to the wells for an additional 2 hours. After washing, a substrate solution was added to each well for 30 minutes. Cytokine concentrations were quantified by optical density readings at 450 nm. Each sample was run in triplicate with known standards.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis for homogeneity as well as Pearson’s correlations (significance: p<0.05, SPSS 15.0 software, Armonk, New York).Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated.

Results

Physiologic and Laboratory Parameters

Blood pressure was maintained at a fixed MAP of 40 mmHg during shock with a correspondingly elevated heart rate that did not return to baseline following the 60 minutes of resuscitation (table 1). This profound degree of shock was associated with a markedly elevated lactate level that did not return to baseline upon resuscitation (table 1). While hyperkalemia and hyponatremia developed during shock, electrolytes normalized with resuscitation. As previously described, this decompensated shock model resulted in significant anemia following resuscitation.(8) During shock and resuscitation, the respiratory rate increased significantly and was accompanied by an increase in pO2 and a decrease in pCO2.

TABLE 1.

Hemodynamic parameters, acid base profile and serum markers

| Groups |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control n=5 |

Severe Shock n=6 |

Resuscitation n=6 |

|

| MAP (mmHg) | 113 ± 6 | 42 ± 2 * | 78 ± 10 *§ |

| HR (bpm) | 435 ± 40 | 472 ± 37 | 471 ± 52 |

| pH | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 7.05 ± 0.21 * | 7.20 ± 0.11 * |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 17.2 ± 3.1 * | 10.2 ± 3.0 *§ |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 50.9 ± 6.3 | 16.6 ± 4.8 * | 28.2 ± 3.4 *§ |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 84.2 ± 9.3 | 127.8 ± 9.4 * | 113.2 ± 13.0 *§ |

| HCO3−(mmol/L) | 30.8 ± 3.0 | 5.4 ± 3.8 * | 11.3 ± 2.8 *§ |

| O2Sat (%) | 96.0 ± 1.4 | 96.8 ± 1.6 | 97.2 ± 1.2 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 22.3 ± 3.1 | 29.3 ± 3.8 * | 25.3 ± 3.2 |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 135.2 ± 2.9 | 128.2 ± 2.7 * | 130.3 ± 6.1 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 1.4 * | 5.0 ± 0.6§ |

| Cl− (mmol/L) | 102.3± 1.8 | 101.2 ± 2.0 | 100.3 ± 4.3 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.3 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.2 * | 3.8 ± 0.3 *§ |

p<0.05 vs. Control group

p<0.05 vs. Severe Shock group

Values are mean ± SD

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential, ROS, and Oxygen Consumption During Shock and Resuscitation

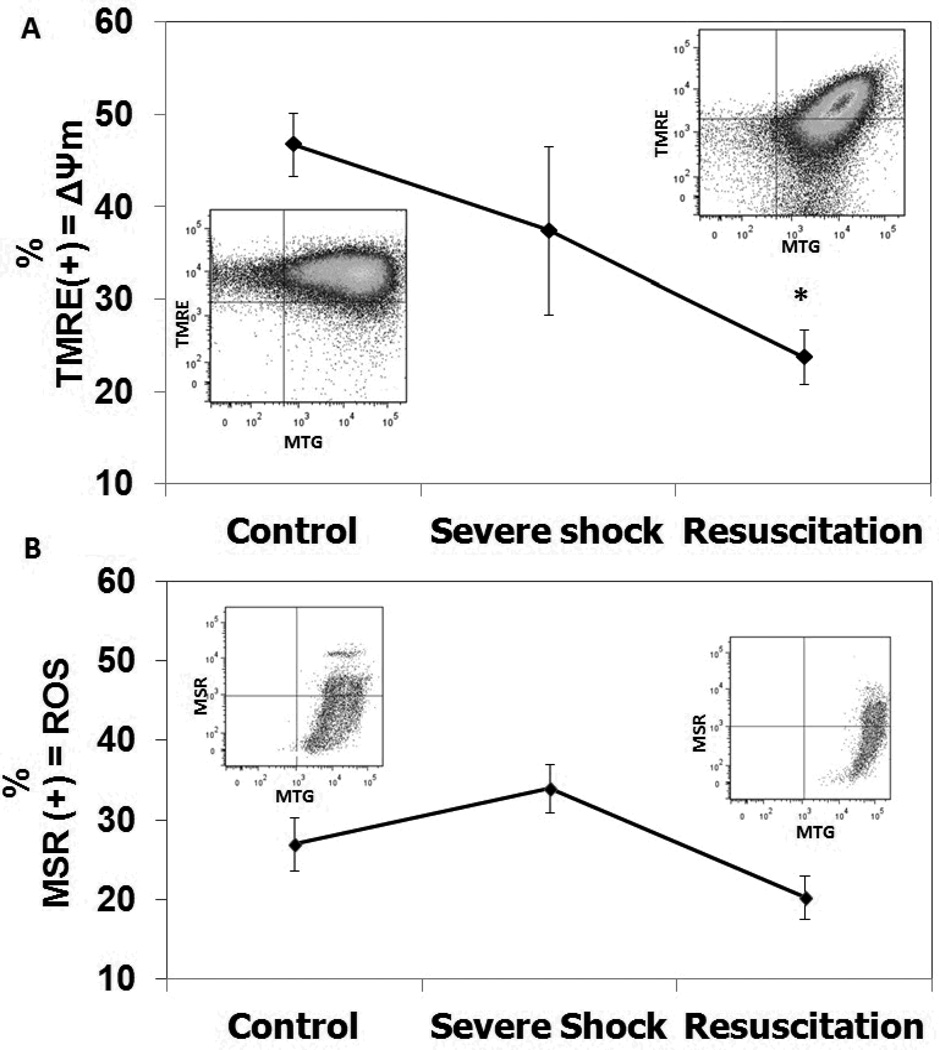

When compared to controls, mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) significantly decreased following resuscitation (23.77 ± 2.98% vs. 46.77 ± 6.95%, p<0.05, Figure 2A). There was no statistically significant increase in ROS production in either the severe shock or resuscitation groups relative to controls (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. PBMC mitochondrial profile assessed by flow cytometry.

A. Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE). B. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was assessed using Mitosox Red (MSR).100,000 events were recorded and only cells that stained positive for MitoTracker Green (MTG) were considered for analysis. Groups include Control, Severe Shock and Resuscitation. Mean values ± SEM are displayed; *p<0.05 vs. Control group), using ANOVA.

Using high-resolution respirometry, PBMC basal respiration significantly decreased after resuscitation when compared to controls (4.8 ± 2.3 vs. 34.29 ± 10.1 pmol O2 x s−1 × 10−6 PBMCs, p<0.05). Although the proton leak respiration and the reserve capacity remained unchanged following severe shock and resuscitation, oxygen consumption was significantly affected at the expense of respiration linked to mitochondrial ATP production (1.54 ± 3.39 vs. 25.92 ± 7.18 pmol O2 x s−1 × 10−6 PBMCs, p<0.05). We also found an increase in the residual, non-electron transport chain-linked oxygen consumption (rotenone + antimycin A-insensitive respiration) in the severe shock group compared to the control and resuscitation groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Bioenergetic Profile of PBMC’s

| Groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen consumption parameters (pmol O2/s × 106 PBMC) |

Control n = 5 |

Severe Shock n = 6 |

Resuscitation n = 5 |

Control PBMCs post Resuscitation plasma n = 3 |

Post Resuscitation PBMCs Control plasma n = 3 |

| Basal Respiration | 34.3 ± 10.1 | 26.9 ± 7.5 | 4.8 ± 2.3*§ | 15.3 ± 10.3* | 28.0 ± 6.5† |

| Leak Respiration | 8.4 ± 4.1 | 7.8 ± 2.4 | 3.3 ± 3.0 | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 2.9 |

| Maximal Respiration | 40.9 ± 10.7 | 28.3 ± 10.9 | 6.7 ± 4.3*§ | 26.5 ± 21.7 | 39.6 ± 16.0† |

| Reserve Capacity | 6.6 ± 7.1 | 0.8 ± 8.0 | 1.9 ± 2.8 | 11.2 ± 11.8 | 11.6 ± 4.9† |

| ATP-linked Respiration | 25.9 ± 7.2 | 16.7± 7.8 | 1.5 ± 3.4*§ | 11.5 ± 8.2* | 22.2 ± 8.4† |

| Residual Respiration | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 2.9* | 2.1 ± 1.1§ | 8.2 ± 6.1 | 4.7 ± 2.2 |

p<0.05 vs. Control group

p<0.05 vs. Severe Shock group

p<0.05 vs. Resuscitation group

Values are mean ± SD

The Impact of Plasma on PBMC Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Circulating plasma factors significantly impacted PBMCs mitochondrial function. Healthy control PBMCs adopted a mitochondrial phenotype similar to that observed in post-resuscitation PBMCs when incubated with plasma collected following resuscitation. Specifically, the basal, maximal and ATP-linked respiration in control PBMCs treated with post-resuscitation plasma decreased significantly and approached values observed in PBMCs subjected to shock and resuscitation. Conversely, the mitochondrial function of PBMCs harvested after resuscitation was rescued by treating with healthy control plasma (Table 2).

Immune Response and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Following Shock and Resuscitation

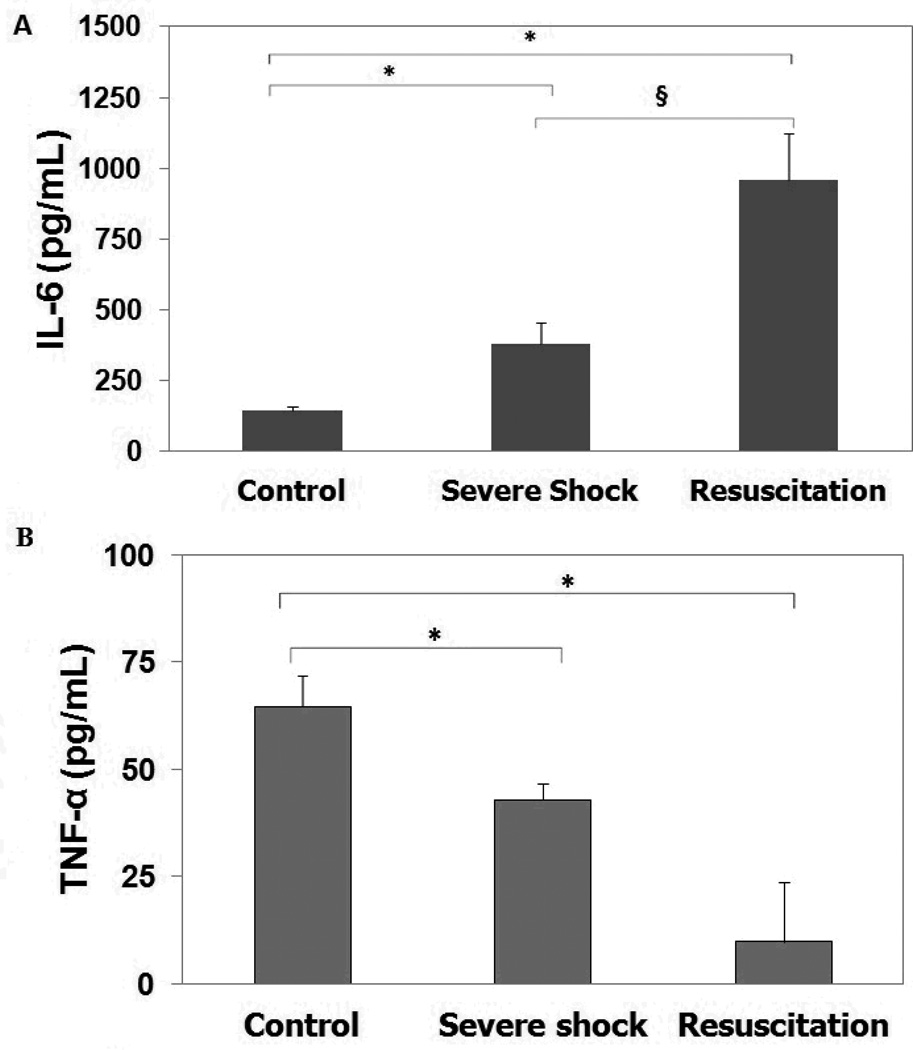

Serum concentrations of IL-6, increased 2-fold during severe shock and 8-fold with resuscitation (Figure 3a). Following severe shock and resuscitation, TNF-α production in response to endotoxin stimulation, however, decreased significantly. When compared to controls, PBMCs experienced a significant decrease in stimulated TNF-α secretion following shock and resuscitation (~34% and ~75% decrease respectively, p<0.05, Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Cytokine levels.

A. Serum basal levels of IL-6. B. Serum levels of TNF-α after 24-hour incubation with LPS. Groups include Control, Severe Shock and Resuscitation. Values are displayed as Mean ± SD; *p<0.05 when compared to Control group) and §p<0.05 when compared to Severe Shock group), using ANOVA.

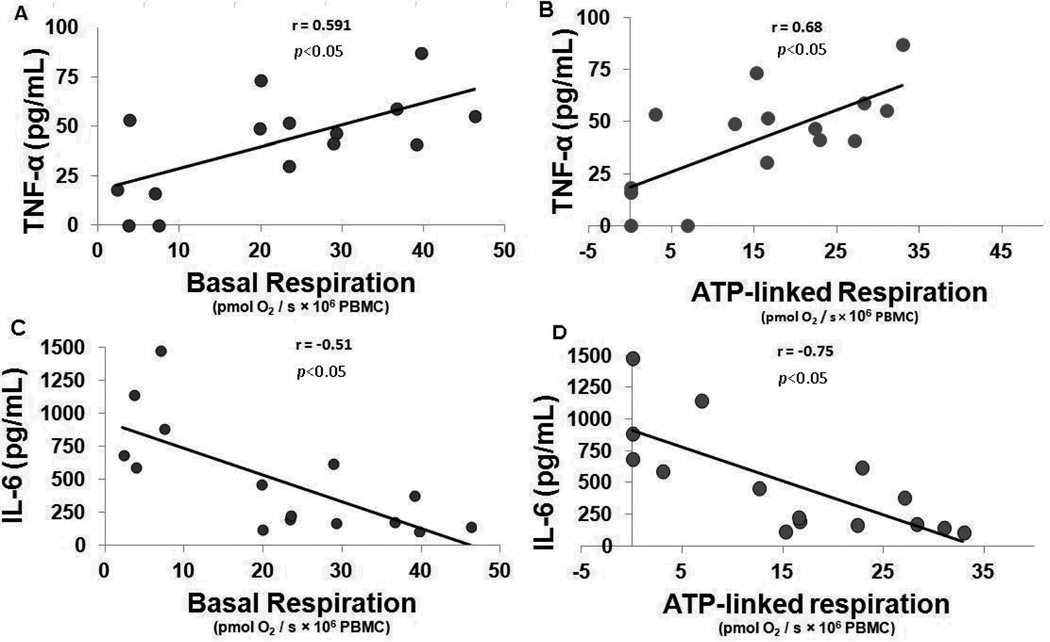

Stimulated TNF-α levels significantly correlated with basal (r = 0.591, p = 0.006), maximal (r = 0.642, p = 0.002) and ATP-linked respiration (r = 0.68, p < 0.05). In contrast, IL-6 levels inversely correlated with these same parameters (Figure 4). Lactate did not correlate with either levels of TNF-α or IL-6 (data not shown).

Figure 4. Correlations between mitochondrial respiration and cytokine levels.

A. TNF-α production and Basal respiration (r=0.591, p<0.05) B. TNF-α production and ATP-linked respiration; (r=0.68, p<0.05). C. IL-6 levels and Basal respiration (r=−0.51, p<0.05). D. IL-6 levels and ATP-linked respiration (r=−0.75, p<0.05) Using Pearson’s correlation, both basal and ATP-linked mitochondrial respiration positively correlated with the LPS-stimulated TNF-α production. Mitochondrial dysfunction was associated to low production of TNF-α while optimum mitochondrial function corresponded to a robust TNF-α response to LPS stimulation. In contrast, there was a negative correlation between mitochondrial respiration and IL-6 levels. Both basal and ATP-linked respirations were suppressed in the presence of high IL-6 levels while normal mitochondrial function was observed in the setting of low IL-6.

Discussion

Trauma and hemorrhagic shock have been shown to impair cell-mediated immunity (9,10). Given the immune response is a highly energetic process (15), we investigated the possible relationship between PBMC mitochondrial function and the development of immune dysfunction using a decompensated hemorrhagic shock model. In the present study, PBMCs demonstrated significant mitochondrial dysfunction as well as diminished capacity to respond to endotoxin challenge following severe blood loss and resuscitation. Importantly, impaired mitochondrial respiration correlated well with depressed TNF-α response and elevated IL-6 levels – a cytokine pattern that has been clinically associated with increased infectious complications.(9,11,14) Interestingly, we also found that plasma factors may directly influence mitochondrial function in PBMCs during shock and resuscitation.

Multiple organ failure in seriously injured patients may result from impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics.(18–21,29–30) In addition to directly harming tissue, impaired mitochondrial function and apoptosis may directly contribute to the depletion of immune cells and the development of immunosuppression.(4,31) PBMCs in our model demonstrated significant mitochondrial dysfunction when subjected to hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation with diminished basal rates of oxygen consumption as well as dramatically impaired respiration linked to ATP production. Importantly, the bioenergetic failure observed following resuscitation was also associated with a significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential can trigger opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore thus promoting apoptosis, cell death, and the development of immune suppression,(18,31) Longer term studies, however, are needed to determine if the mitochondrial dysfunction observed in our study translates to PBMC apoptosis or increased infectious complications.

Both TNF-α and IL-6 play a critical role in the post-traumatic immune response. Although TNF-α levels are frequently elevated following trauma, a reduced capacity to produce TNF-α by monocytes after ex vivo stimulation with LPS has been associated with adverse outcomes following both sepsis and trauma (13,14,30). IL-6, on the other hand, a cytokine released from T cells, macrophages, damaged endothelial cells and fibroblasts, can serve as both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine.(6,11) Notably, elevated IL-6 levels have been repeatedly found to be a poor prognostic indicator in injured patients.(11,32,33) In our study, we also observed a significant decrease in LPS-stimulated TNF-α secretion as well as elevated IL-6 levels following hemorrhagic shock. As such, our model recapitulates a cytokine pattern that has been clinically associated with increased infectious complications and mortality.(9,11,14)

Although there is very little data exploring the relationship between mitochondrial capacity and immune function in trauma patients, several recent studies have demonstrated a direct link between mitochondrial dysfunction, immunosuppression, and poor clinical outcome in sepsis. Japiassú et al noted that in PBMCs isolated from septic patients, failure to raise oxygen consumption in response to ADP was associated with impaired F1F0 ATP synthase activity. Moreover, this defect was significantly more pronounced in patients who did not survive.(16) Impaired PBMCs oxidative phosphorylation has also been associated with down regulation of HLA-DR expression.(14) Given that HLA-DR expression is essential for antigen presentation and activation of the immune system, it is not surprising that decreased HLA-DR expression has been associated with increased septic complications and mortality (34,35). Mitochondrial dysfunction in PBMCs may also contribute to a state of immunosuppression and increased septic complications in the setting of trauma.(32) In our study, mitochondrial dysfunction in PBMCs clearly correlated with impaired immune function as measured by TNF-α response to LPS stimulation. This association was strongest when respiration linked to ATP production was investigated. We also noted a negative relationship between IL-6 levels and mitochondrial function. As IL-6 levels increased, basal and ATP linked respiration became significantly more impaired. Although there is increasing evidence that IL-6 directly impairs mitochondrial function in a variety of cell types, further research is needed to determine if the observed elevation in IL-6 directly causes immunosuppression or is merely a proxy for mitochondrial impairment following shock and resuscitation.(36,37)

The mitochondrial dysfunction observed in PBMCs following shock and resuscitation, however, may not represent a permanent bioenergetic defect. Our studies demonstrated that incubating PBMCs harvested after resuscitation with healthy plasma resulted in a marked functional improvement in oxygen consumption; whereas, healthy PBMCs developed significant mitochondrial impairment when mixed with post-resuscitation plasma. Belikova et al observed a similar change in PBMC phenotype in sepsis. Healthy PBMCs adopted the oxygen consumption pattern of septic cells when incubated in septic plasma while septic PBMCs recovered mitochondrial function when incubated in healthy plasma.(17) Although it is unclear how the plasma milieu influences mitochondrial function in either hemorrhagic shock or sepsis, possible explanations include direct mitochondrial inhibition by elevated levels of nitric oxide, prostaglandins or cytokines (17, 38, 39).

Although our findings suggest hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation significantly impact PBMC mitochondrial and immune function, there are several limitations to our study. Most importantly, although this model of decompensated shock has been well-described (22), trauma patients are not typically resuscitated with only crystalloid and the development of profound anemia seen with this model may decrease both oxygen content and delivery.(28) That being said, in our study the oxygen tension actually increased during hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation suggesting that the injury observed in PBMCs was not secondary to serum hypoxia. Moreover, previous experiments have demonstrated that resuscitation with a combination of blood and crystalloid, does not improve either mortality or the degree of immunosuppression following hemorrhagic shock when compared to resuscitation with crystalloid alone. (24,40) Additionally, although we did not see an increased production of ROS in our model, our sample size is small and a larger number would be needed to ensure that we do not have a type II error. Finally, we only investigated the effects of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation on PBMC function over a short duration. Further studies are needed to determine if the mitochondrial dysfunction we observed persists despite adequate resuscitation or results in long-term impairment and increased infectious complications.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that PBMCs develop significant mitochondrial dysfunction following hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation that is associated with a blunted response to endotoxin and elevated IL6 levels. Impaired PBMC bioenergetics may contribute to the immunosuppression observed following significant blood loss and warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported, in part, by grant 1K08GM097614-01 from the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- José Paul Perales Villarroel, M.D.: literature search, study design, experimental procedures, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and figures.

- Yuxia Guan, B.S.: experimental procedures and data analysis.

- Evan Werlin, B.S.: literature search and study design.

- Mary A. Selak, Ph.D.: data analysis and data interpretation.

- Lance B. Becker, M.D.: data analysis and data interpretation.

- Carrie Sims, M.D, M.S.: literature search, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and figures.

This paper has been presented in the 2013 EAST Annual Scientific Assembly

The presented authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jose Paul Perales Villarroel, Email: jose.peralesvillarroel@uphs.upenn.edu.

Yuxia Guan, Email: Yuxia.Guan@uphs.upenn.edu.

Evan Werlin, Email: evan.werlin@gmail.com.

Mary A. Selak, Email: Mary.Selak@uphs.upenn.edu.

Lance B. Becker, Email: Lance.Becker@uphs.upenn.edu.

Carrie Sims, Email: Carrie.Sims@uphs.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborn TM, Tracy JK, Dunne JR, Pasquale M, Napolitano LM. Epidemiology of sepsis in patients with traumatic injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2234–2240. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145586.23276.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glance LG, Stone PW, Mukamel DB, Dick AW. Increases in mortality, length of stay, and cost associated with hospital-acquired infections in trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2011;146(7):794–801. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(2):138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPS cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cinel I, Opal SM. Molecular biology of inflammation and sepsis: a primer. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:291–304. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819267fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM. Compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh CH, Nickel EA, Hsu JT, Schwacha NG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Trauma-hemorrhage and hypoxia differentially influence Kupffer cell phagocytic capacity. Ann Surg. 2009;250:995–1001. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0ebf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu YX, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Prolonged immunodepression after trauma and hemorrhagic Shock. J Trauma. 1998;44:335–341. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199802000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seitz DH, Perl M, Liener UC, Tauchmann B, Braumüller ST, Brückner UB, Gebhard F, Knöferl MW. Inflammatory alterations in a novel combination model of blunt chest trauma and hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;70:189–196. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d7693c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jawa RS, Anillo S, Huntoon K, Baumann H, Kulaylat M. Interleukin 6 in Surgery, Trauma, and Critical Care—Part II: Clinical Applications. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:73–87. doi: 10.1177/0885066610384188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jawa RS, Anillo S, Huntoon K, Baumann H, Kulaylat M. Analytic Review: Interleukin-6 in Surgery, Trauma, and Critical Care: Part I: Basic Science. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:3–12. doi: 10.1177/0885066610395678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, Volk HD, Kox W. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: Restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–681. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ploder M, Pelinka L, Schmuckenschlager C, Wessner B, Ankersmit HJ, Fuerst W, Redl H, Roth E, Spittler A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production and not monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression is correlated with survival in septic trauma patients. Shock. 2006;25:129–134. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000191379.62897.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buttgereit F, Burmester GR, Brand MD. Bioenergetics of immune functions: Fundamental and therapeutic aspects. Immunol Today. 2000;21:192–199. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japiassú AM, Santiago AP, d’Avila JCP, Garcia-Souza LF, Galina A, Castro Faria-Neto HC, Bozza FA, Oliveira MF. Bioenergetic failure of human peripheral blood monocytes in patients with septic shock is mediated by reduced F1Fo adenosine-5′-triphosphate synthase activity. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eda5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belikova I, Lukaszewicz AC, Faivre V, Damoisel C, Singer M, Payen D. Oxygen consumption of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in severe human sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2702–2708. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000295593.25106.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adrie C, Bachelet M, Vayssier-Taussat M, Russo-Marie F, Bouchaert I, Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM, Pinsky MR, Dhainaut JF, Polla BS. Mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis peripheral blood monocytes in severe human sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:389–395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2009088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cairns CB. Rude unhinging of the machinery of life: metabolic approaches to hemorrhagic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001 Dec;7(6):437–443. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozlov AV, Bahrami S, Calzia E, Dungel P, Gille L, Kuznetsov AV, Troppmair J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis: do ICU patients die from mitochondrial failure? Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(1):41. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson DE, Nguyen PX, Soane L, Fiedler SM, Fiskum G, Chiu WC, Scalea TM. Hypotensive hemorrhage increases calcium uptake capacity and bcl-xl content of liver mitochondria. Shock. 2007;27:192–198. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000238067.77202.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayala A, Wang P, Chaudry IH. Shock Models: Hemorrhage. In: Souba W, Wilmore D, editors. Surgical Research. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 325–327. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P, Chaudry IH. Crystalloid resuscitation restores but does not maintain cardiac output after severe hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 1991;50:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90241-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh S, Chaudry KI, Chaudry IR. Crystalloid is as effective as blood in the resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1992;215:377–382. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pesta D, Gnaiger E. High-resolution respirometry. OXPHOS protocols for human cells and permeabilized fibres from small biopsies of human muscle. In: Palmeria C, Moreno A, editors. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics: methods and protocols. Vol. 810. New York: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 25–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sjövall F, Morota S, Hansson MJ, Friberg H, Gnaiger E, Elmér E. Temporal increase of platelet mitochondrial respiration is negatively associated with clinical outcome in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R214. doi: 10.1186/cc9337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in primary cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrial reserve capacity is a sensitive measure of cellular stress. Seahorse Bioscience. Avaliable at: http://www.seahorsebio.com/learning/app-notes/cos.php Accessed August 15, 2012.

- 28.Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Conroy MJ, Mulier KE, Myers D, Gruessner A, Hammer BE. Tissue energetics as measured by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy during hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2004;21:58–64. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000101674.49265.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhee P, Langdale L, Mock C, Gentilello LM. Near-infrared spectroscopy: continuous measurement of cytochrome oxidation during hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:166–170. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh YC, Athar M, Chaudry IH. When apoptosis meets autophagy: deciding cell fate after trauma and sepsis. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(3):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tschoeke SK, Ertel W. Immunoparalysis after multiple trauma. Injury. 2007;38:1346–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biffl WL, Moore EE, Moore FA, Peterson VM. Interleukin-6 in the injured patient; marker of injury or mediator of inflammation. Ann Surg. 1996;224:647–664. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouel-Chéron A, Allaouchiche B, Guignant C, Davin F, Floccard B, Monneret G. Early Interleukin-6 and slope of monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR: A powerful association to predict the development of sepsis after major trauma. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033095. Epub 2012 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venet F, Tissot S, Debard AL, Faudot C, Crampé C, Pachot A, Ayala A, Monneret G. Decreased monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression after severe burn injury: Correlation with severity and secondary septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1910–1917. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275271.77350.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White JP, Puppa MJ, Sato S, Gao S, Price RL, Baynes JW, Kostek MC, Matesic LE, Carson JA. IL-6 regulation on skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling during cancer cachexia in the ApcMin/+ mouse. Skelet Muscle. 2012;2:14. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji C, Chen X, Gao C, Jiao L, Wang J, Xu G, Fu H, Guo X, Zhao Y. IL-6 induces lipolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction, but does not affect insulin-mediated glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2011;43(4):367–375. doi: 10.1007/s10863-011-9361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raffaella T, Fiore F, Fabrizia M, Francesco P, Arcangela I, Salvatore S, Luigi S, Nicola B. Induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in human fibroblast cultures exposed to serum from septic patients. Life Sci. 2012;91:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrabou G, Moren C, Lopez S, Tobias E, Cardellach F, Miro O, Casademont J. The effects of sepsis on mitochondria. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:392–400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ba ZF, Wang P, Koo DJ, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Alterations in tissue oxygen consumption and extraction after trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2837–2842. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmand JF, Ayala A, Chaudry IR. Effects of trauma, duration of hypotension, and resuscitation regimen on cellular immunity after hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1076–1083. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]