Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), known as an important cellular signaling molecule, plays critical roles in many physiological and/or pathological processes. Modulation of H2S levels could have tremendous therapeutic value. However, the study on H2S has been hindered due to the lack of controllable H2S releasing agents which could mimic the slow and moderate H2S release in vivo. In this work we report the design, synthesis and biological evaluation of a new class of controllable H2S donors. Twenty five donors were prepared and tested. Their structures were based on a perthiol template, which was suggested to involve in H2S biosynthesis. H2S release mechanism from these donors was studied and proved to be thiol-dependent. We also developed a series of cell-based assays to access their H2S related activities. H9c2 cardiac myocytes were used in these experiments. We tested lead donors’ cytotoxicity and confirmed their H2S production in cells. Finally we demonstrated that selected donors showed potent protective effects in an in vivo murine model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, through a H2S related mechanism.

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide, thiol, donor, myocyte, ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been recognized as an important cellular signalling molecule, much like nitric oxide (NO).1–6 The endogenous formation of H2S is attributed to enzymes including cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur-transferase (MPST).7–10 These enzymes convert cysteine or cysteine derivatives to H2S in different tissues and organs. Recent studies have suggested that the production of endogenous H2S and the exogenous administration of H2S can exert protective effects in many pathologies.1,2 For example, H2S has been shown to relax vascular smooth muscle, induce vasodilation of isolated blood vessels, and reduce blood pressure. H2S can also inhibit leukocyte adherence in mesenteric microcirculation during vascular inflammation in rats, suggesting H2S is a potent anti-inflammatory molecule. In addition, H2S may intereact with S-nitrosothiols to form thionitrous acid (HSNO), the smallest S-nitrosothiol, whose metabolites, such as NO+, NO, and NO−, have distinct but important physiological consequences.11 These results strongly suggest that modulation of H2S levels could have potential therapeutic values.

To explore the biological functions of H2S, researchers started to use H2S releasing compounds (also known as H2S donors) to mimic endogenous H2S generation.12–14 The idea is similar to the well-studied nitric oxide (NO) donors. Currently there are many options about NO donors, including organic nitrates, nitrites, diazeniumdiolates, N-nitrosoamines, N-nitrosimines, S-nitrosothiols, hydroxylamines, N-hydroxyguanidines, etc. Moreover, many strategies, such as light, pH, enzymes, etc., can be used to trigger NO generation from these donors. In contrast, currently available H2S donors are still very limited. These donors include: 1) sulfide salts, such as Na2S, NaHS, and CaS, have been widely used in the field. These inorganic donors have the advantage of rapidly enhancing H2S concentration. The maximum concentration of H2S released from these salts can be reached within seconds. However such a fast generation may cause acute changes in blood pressure. In addition, since H2S is highly volatile in solutions, the effective residence time of these donors in tissues may be very short.15,16 2) Naturally occurring polysulfide compounds such as diallyl trisulfide (DATS) are also employed as H2S donors in some studies. DATS can vasodilate rat aortas17 and protect rat ischemic myocardium18 via a H2S-related manner, but the simplicity of the structure limits its application as H2S donors. 3) Synthetic H2S donors have recently emerged as useful tools. GYY4137,19 which is a Lawesson’s reagent derivative, releases H2S via hydrolysis both in vitro and in vivo and it exhibits some interesting biological activities20,21 such as anti-inflammation. 22–24 H2S release from GYY4137 is relatively low (< 10 % of H2S was released from this molecule after 7 days).25 Dithiolthione is another structure which releases H2S in aqueous solution.13 However the detailed mechanism is still unclear. A major limitation of current donors is that H2S release is largely uncontrollable. Modifications that are made between the time that a solution is prepared and the time that the biological effect is measured can dramatically affect results. In our opinion, ideal H2S donors should be stable by themselves in aqueous solutions. The release of H2S (both the time and the rate) should be controllable (upon activation by certain factors). Such donors will not only be useful research tools for H2S researchers but also have unique therapeutic benefits themselves.

The research in our laboratory focuses on the development of controllable H2S donors. In 2011 we discovered a series of N-(benzoylthio)benzamide derivatives as thiol-activated H2S donors.26 These compounds are stable in aqueous solutions and in the presence of some cellular nucleophiles. Upon activation by cysteine or reduced glutathione (GSH), the compounds could produce H2S (Scheme 1a).26 In this process, cysteine perthiol (also known as thiocysteine) is believed to be a key intermediate. It should be noticed that cysteine perthiol is also involved in H2S biosynthesis catalysed by CSE (Scheme 1b).13,27 These findings suggest that the perthiol (Scheme 1c) can be a useful template for the design of controllable H2S donors. Herein we report the development of perthiol based donors and their activities in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (MI/R) injury.

Scheme 1.

a) Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) release from N-(benzoylthio)benzamide derivatives. b) H2S biosynthesis catalyzed by cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE). c) Idea of perthiol based H2S donors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Primary perthiol based H2S donors

Perthiols are known to be unstable species.28–30 We expected a protecting group on -SH could enhance the stability. In addition, the protecting group could allow us to develop different strategies to retrieve perthiol, therefore, achieving the regulation of H2S release. With this idea in mind, we decided to test cysteine-based perthiol derivatives 2 (Scheme 2). Acyl groups were used as the protecting group on perthiol moieties.

Scheme 2.

a) H2S generation data of cysteine-based donors 2. b) Proposed reactions of 2.

The synthesis of four cysteine-based donors (2a–d) was described in Supplementary Scheme S1. N-Benzoyl cysteine methyl ester was first treated with 2-mercapto pyridine disulfide to provide a cysteine-pyridine disulfide intermediate, which was then treated with corresponding thioacids to give the desired donor compounds. Using the procedure reported previously,26 we analyzed H2S release capabilities of these donors in the presence of cysteine and GSH. As shown in Scheme 2, these donors indeed could generate H2S in the presence of thiols. Compared to N-(benzoylthio)-benzamide type donors, however, these donors showed much decreased ability of H2S generation (read from their peaking concentrations). The initial concentration of the donors was 150 μM while the maximum H2S concentration formed was less than 15% (by cysteine) or 8% (by GSH).

Scheme 3.

a) H2S release curve of donor 8a. b) H2S generation data of selected penicillamine-based donors.

From reaction mechanism point-of-view, we expected the free SH of cysteine or GSH would undergo a thioester exchange with the acyl group to produce perthiol 4 (pathway A, Scheme 2b), which in turn should lead to H2S formation. However, it was also possible that SH reacted with the acyl-disulfide linkage to form a new disulfide 5 and thioacid 6 (pathway B). We found that thioacids could not release H2S even in the presence of cysteine or GSH under the conditions used in our experiments (see Supporting information Figure S1).31 Therefore, H2S release from donors 2 was diminished due to the involvement of pathway B.

Tertiary perthiol based H2S donors

We envisioned that the steric hindrance on α-carbon of the disulfide bridge should prevent the reactions through pathway B, therefore enhance H2S formation. As such we decided to prepare a series of penicillamine-based perthiol derivatives 8 (Scheme 3a). The general synthesis of this series of donors was described in Supplementary Scheme S2. Briefly, C- and N-protected penicillamine was first treated with 2, 2′-dibenzothioazolyl disulfide to provide a penicillamine-benzothioazolyl disulfide intermediate. It was then treated with corresponding thioacids to furnish the desired penicillamine-based donors. Both steps gave good yields for all of the substrates. These donor compounds proved to be stable in aqueous solutions. In the presence of cysteine or GSH, we observed a time-dependent H2S generation. The representative H2S release curves of 8a were shown in Scheme 3. With an initial concentration at 100 μM, the maximum H2S concentration formed was ~ 80 μM (with cysteine), which demonstrated the efficiency of this compound as H2S donor. After reaching the maximum value, H2S concentration started to drop due to the volatilization.15

We expected the change of acyl substitutions could affect the rate of thioester exchange and regulate H2S generation. Therefore a series of acyl substitution modified donors (19 compounds in total) were prepared and tested. The H2S generation data of 9 representative compounds were summerized in Scheme 3b. Data of the rest compounds are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Generally, electron withdrawing groups on the phenyl group led to faster H2S generation while electron donating groups led to slower H2S release. We also observed significant steric effects on H2S formation. More sterically hindered substrates (compounds 8o, 8r, 8s) resulted in slower H2S release (with decreased H2S amounts) or even no release at all. In addition, we found that cysteine always caused higher/faster H2S release compared to GSH. This is likely due to the fact that cysteine, compared with GSH, is a smaller molecule and can react faster with the thioester group. These results demonstrated that H2S release from these perthiol based donors could be regulated via structural modifications.

H2S release mechanism study

To understand the mechanism of H2S release from these donors, we studied the reaction between 8a and a cysteine derivative 9 (3 eq.). As shown in Scheme 4, we confirmed the formation of a thioester 10, an asymmetric disulfide 12, a free thiol 13, as well as cysteine disulfide 15. Based on these reaction products, we proposed the mechanism as follows: the reaction is initiated by a thioester exchange between 8a and 9 to form a new thioester 10 and perthiol 11. Both S atoms of 11 can be attacked by cysteine.32 Therefore two possible pathways exist: a) the cysteine attacks the internal S to yield disulfide 12 and liberate H2S. b) The external S is attacked to form thiol 13 and cysteine perthiol 14. Then another molecule of cysteine 9 reacts with 14 to form disulfide 15 and release H2S. In this process it is also possible that 13 reacts with 14 to form disulfide 12 and release H2S.

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism of H2S generation.

Biological evaluation of perthiol based H2S donors

With these donors in hand, we next explored their therapeutic benefits. Recent studies with animal models suggested that H2S can protect cardiovascular system against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (MI/R) injury.8, 17, 33–35 Several groups have shown that H2S, when applied both at the time of reperfusion and as a preconditioning reagent, exhibits the cardioprotection by different mechanisms, such as preserving mitochondrial function,36 reducing oxidative stress,34 decreasing myocardial inflammation,37 and improving angiogenesis.38 We envisioned that our perthiol-based donors might exhibit similar myocardial protective effects in an in vivo model of murine MI/R injury.

Before conducting animal experiments, we tested cytotoxicity of two representative donors (8a/8l) in H9c2 cardiac myocytes. The cell viability was detected using cell counter kit (CCK)-8 assay (Figure 1). After 24-hour exposure of H9c2 cells to 8a and 8l at varied concentrations (0 to 100 μM), cell viability did not decrease. Interestingly the exposure of cells to 8a and to 8l at concentrations of 12, 25, 50, and 100 μM, increased cell viability percentage (at the level compared to 400 μM NaHS). The results of these studies indicate that these perthiol-based donors do not promote cytotoxicity in cardiac cells at the doses we have tested. We also determined cell viability through the evaluation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration. The results are shown in supplementary Figure S3. Donors 8a and 8l did not lead to ROS increase, which confirms the safety of the donors.

Figure 1.

Effects of 8a and 8l on cell viability. H9c2 cells were treated with different concentrations of 8a or 8l (12 to 100 μM) for 24 h. The cell counter kit (CCK)-8 assay was performed to measure cell viability. Data were shown as the mean ± SD (n = 8). **P < 0.01 versus control group.

We wondered if our donors indeed could release H2S when interacting with myocytes and then conducted experiments to address this question. As shown in Figure 2, H9c2 cells were incubated with the donors (8a and 8l) for 30 minutes, respectively. After that a selective H2S fluorescent probe, WSP-1,39 was applied into the cells to monitor the production of H2S. As expected, donor-treated cells (Figure 2b and 2c) shown much enhanced fluorescent signals compared to vehicle treated cells (Figure 2a). The image of positive control (with H2S) is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. In addition, we did not observe shape changes of the cells after the treatment. These results demonstrated that perthiol based donors can release H2S when interacting with H9c2 cells and H2S generation can be evaluated by fluorescent image.

Figure 2.

H2S production from 8a and 8l in H9c2 cells. Cells were incubated with vehicle (A), 100 μM 8a (B), and 100 μM of 8l (C) for 30 min. After removal of excess donors, 250 μM of a H2S fluorescent probe (WSP-1) was added. Images were taken after 30 min.

Finally we tested myocardial protective effects of donors 8a and 8l against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury in a murine model system. In these experiments, mice were subjected to 45 minutes of left ventricular ischemia followed by 24 hours reperfusion. Compounds 8a, 8l or vehicle were administered into the left ventricular lumen at the 22.5 minutes of myocardial ischemia. All animal groups displayed similar area-at-risk per left ventricle (AAR/LV), which means surgery caused similar risk. However, compared to vehicle treated mice, mice receiving 8a or 8l displayed a significant reduction in circulating levels of cardiac troponin I and myocardial infract size per area-at-risk (Figure 3 B–C). For example, a 500 μg/kg bolus of 8l maximally reduced INF/AAR by ~50%, which was a significant protection. These results demonstrated that perthiol based compounds can exhibit H2S-mediated cardiac protection in MI/R injury and these compounds may have potential therapeutic benefits.

Figure 3.

Cardioprotective effects of compounds 8a and 8l in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. 8a, 8l or vehicle were injected in vivo at the 22.5 min of ischemia. (A) Structures of donors. (B) Circulating cardiac troponin I levels at following 45 min of MI and 2 h of reperfusion. Troponin-I was significantly (p < 0.01) reduced with either 8a or 8l. (C) Myocardial area-at-risk (AAR) per left ventricle (AAR/LV) and infarct size per area-at-risk (INF/AAR) were assessed in vehicle (n = 14) and donor treated animals (n = 14) at 24 h following MI/R. AAR/LV was similar among all groups. INF/AAR was significantly (p < 0.05) smaller in animals treated with either 8a or 8l as compared to vehicle. (D) Representative photomicrographs of a midventricular slice after MI/R stained with Evan’s blue and 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride for both vehicle- and donor-treated hearts.

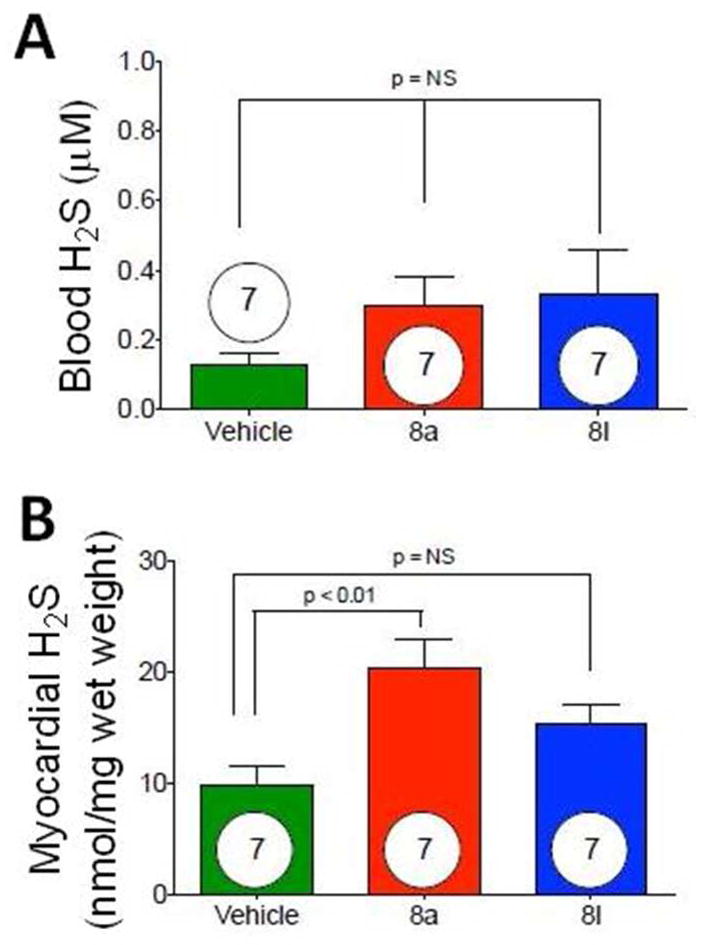

We also tested in vivo H2S production from donors 8a and 8l. As such, donors (1 mg/kg for 8a and 500 ug/kg for 8l) were injected intravenously via tail vein injection. Blood and hearts were obtained at 15 minutes following injection. H2S levels were determined using previously described gas chromatography and chemiluminesence methods.40 As shown in Figure 4, blood and myocardial levels of H2S were significantly (p < 0.01) increased following injection of the donors as compared to controls.

Figure 4.

In vivoH2S levels (μM) in blood (A) and hearts (B) obtained from mice treated with 8a and 8l.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we have developed a series of new H2S donors based on the perthiol template. Their H2S generation is regulated by thiols such as cysteine or GSH. We also demonstrated that H2S release capability from these donors can be manipulated by structural modifications. Moreover, these donors are nontoxic to cardiac cells and their H2S production upon interacting with myocytes can be detected. Some donors exhibited potent myocardial protective effects in MI/R injury, presumably due to H2S generation. It should be noted that H2S generation from these donors is not dependent on specific enzymes such as CBS and CSE. Recently our group tested the effects of some H2S donors on CBS/CSE activity and we did not notice any changes even after weeks.41 Taking together these donors may be potential therapeutic agents. In our in vivo experiments, 8l exhibited better cardioprotective effects than 8a (Figure 3). Interestingly, 8l also exhibited better activity in cell viability test and H2S generation test (Figures 1 and 2). These data suggest that in vitro evaluation of donors may allow us to predicate donors’ in vivo behaviors. Further development of this type of donors and evaluation of their other H2S related biological activities are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

METHOD

Synthesis of 2a–2d

2-Mercapto pyridine disulfide (2.2 g, 10 mmol) was dissolved in 50 mL CHCl3. To this solution was added N-benzoyl cysteine methyl ester (1.2 g, 5 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then concentrated under vacuum. 1.48 g of compound a was obtained as whitesolid by flash chromatography (hexane : ethyl acetate = 2:1). Please see supporting information for character data of a. Synthetic intermediate a, 83 mg, 0.24 mmol, was dissolved in 5 mL CHCl3. To this solution was added thiobenzoic acid (42 mg, 0.3 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The excess thiobenzoic acid was removed by washing with aqueous NaHCO3 solution. The organic layer was separated, dried, and concentrated under vacuum. The final product 2a was purified as white solid by flash chromatography (hexane : ethyl acetate = 10 : 4). m.p. 94–96 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (m, 5H), 5.06 (m, 1H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 3.57 (dd, J = 14.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (dd, J = 14.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 191.3, 170.8, 167.3, 135.3, 134.7, 133.7, 132.1, 129.2, 128.8, 128.0, 127.6, 53.0, 51.8, 40.9; IR (thin film) cm−1 3326, 3056, 2955, 2927, 1748, 1683, 1638, 1520, 1489, 1319, 1203, 883; mass spectrum (ESI/MS) m/z 398.1 [M+Na]+; HRMS m/z 398.0500 [M+Na]+; calcd for C18H17NNaO4S2 398.0497; yield: 81%.

2b–2d were prepared from the corresponding thiolacids using the same procedure as 2a. Their data were reported in the supporting information.

Synthesis of compounds 8a–8s

2, 2′-Dibenzothiazolyl disulfide (4.32g, 13 mmol) was dissolved into 500 mL of CHCl3. To this solution was added a D, L-penicillamine derivative 13 (2.36 g, 9.6 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. Solvent was then removed and the crude mixture was then purified by flash column chromatography (3% v/v MeOH in DCM) to provide the intermediate d as white solid. To a 15 mL CHCl3 solution containing d (822 mg, 2 mmol) was added thiobenzoic acid (1.10 g, 8 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes. Excess thiobenzoic acid was removed by washing with NaHCO3. The organic layer was separated, dried, and concentrated. The final product 8a was purified by flash column chromatography (1% v/v MeOH in DCM) as white solid. m.p. 132–134 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.16 (m, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (m, 2H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.44 (m, 5H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 194.0, 170.4, 168.8, 135.5, 134.8, 129.2, 128.3, 58.7, 53.8, 39.8, 31.6, 27.0, 24.0, 23.5, 20.5, 14.0; IR (thin film) cm−1 3285, 3085, 2962, 2929, 2868, 1684, 1636, 1561, 1527, 1445, 1379, 1202, 1174, 1118, 890, 676; mass spectrum (ESI/MS) m/z 405.1 [M+Na]+; HRMS m/z 383.1411 [M+H]+; calcd for C18H27N2O3S2 383.1463; yield: 94 %.

8b–8s were prepared from corresponding thiolacids using the same procedure as 8a.

H2S Measurement

The reaction was initiated by adding 75 μL stock solution of the donor (40 mM, in THF) into pH 7.4 phosphate buffer (30 mL) containing cysteine (1.0 mM). 1.0 mL of reaction aliquots were periodically taken and transferred to 4.0-mL vials containing zinc acetate (1% w/v, 100 μL), N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine sulfate (20 mM, 200 μL) in 7.2 M HCl and ferric chloride (30 mM, 200 μL) in 1.2 M HCl. The absorbance (670 nm) of the resulted solution (1.5 mL) was determined 15 min thereafter using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Thermo Evolution 300). The H2S concentration of each sample was calculated against a calibration curve of Na2S. The H2S releasing curve was obtained by plotting H2S concentration versus time.

Product analysis

100 mg of 8a (0.26 mmol) was dissolved in 10.0 mL THF/phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (1:1, v/v). Then a cysteine derivative 9 (187 mg, 0.78 mmol) was added into the solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with DCM for 3 times. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and concentrated. Products 10, 12, 13, and 15 were isolated by flash column chromatography (1% v/v MeOH in DCM).

10 and 15 are known compounds. Their data are shown in the supporting information.

12 (1:1 mixture of diastereoisomers): m.p. 73–75 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.84 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (m, 6H), 7.29 (m, 2H), 6.96 (br, 1H), 6.78 (br, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 5.09 (m, 2H), 4.68 (d, J = 9..9 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 6H), 3.29 (m, 6H), 3.07 (m, 2H), 1.97 (s, 6H), 1.35 (m, 20H), 0.86 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.4, 171.2, 170.4 (2C), 169.3, 169.2, 167.4, 167.3, 133.8, 133.7, 132.2, 132.1, 128.8 (2C), 127.5, 127.4, 58.6, 58.4, 53.3, 53.1, 53.0, 52.8, 42.3, 42.2, 39.6, 34.9, 31.8 (2C), 31.5 (2C), 29.3, 25.5, 25.4, 25.3, 24.2, 23.5, 22.9, 20.3, 14.4, 14.0; IR (thin film) cm−1 3300, 3072, 2962, 2934, 2871, 1739, 1645, 1535, 1366, 1228; mass spectrum (ESI/MS) m/z 506.1 [M+Na]+; HRMS m/z 506.1752 [M+Na]+; calcd for C22H33N3NaO5S2 506.1759; yield: 20 %.

13: m.p. 176–177 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.92 (br, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 3.21 (m, 2H), 2.65 (s, 1H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 1.48 (m, 5H), 1.32 (m, 5H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.4, 169.9, 60.4, 46.3, 39.4, 31.5, 31.2, 28.7, 23.6, 20.3, 14.0; IR (thin film) cm−1 3267, 3084, 2967, 2935, 2874, 2558, 1667, 1638, 1537, 1456, 1371, 1241, 1136; mass spectrum (ESI/MS) m/z 269.1 [M+Na]+; HRMS m/z 247.1473 [M+H]+; calcd for C11H23N2O2S 247.1480; yield: 55 %.

Cell viability assay

H9c2 (2-1) cardiomyocytes (H9c2 cells) were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. H9c2 cells at a concentration of 1×105/mL were inoculated in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. H2S donor (8a or 8l) in FBS-free medium was administered and cultured for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by cell counter kit (CCK)-8. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Optical density (OD) of the 8 wells in the indicated groups was used to calculate percentage of cell viability according to the formula below:

H2S release in H9c2 cells

H9c2 cells were inoculated in 6-well plates and cultured overnight. The cells were co-incubated with 100 μM H2S donor, 8a (b) or 8l (c), dissolved in phosphate buffered solution (PBS) at 37°C for 30 min and then the solution in the wells was removed. The cells were then co-incubated with a H2S probe (WSP-1) solution (250 μM in PBS) and surfactant CTAB (500 μM) in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. After the PBS was removed, fluorescence signal was observed by AMG fluorescent microscope (Advanced Microscopy Group, USA).

Cardioprotective effects in MI/R

Animal

Male C57BL/6J mice, 10–12 weeks of age (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were used in the present study. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled animal facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with water and rodent chow provided ad libitum. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Society of Medical Research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (Publication 85-23, Revised 1996). All animal procedures were approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug preparation

On the day of experimentation, test compounds (8a or 8l) were diluted in 0.5 mL of 100% THF solution. For in vivo experiments, the test compounds were further diluted in sterile saline to obtain the correct dosage to be delivered in a volume of 50 μL. The resulting concentration of THF in this dosage was 0.5% v/v. Vehicle consisted of a solution of 0.5% v/v THF in sterile saline.

Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion (MI/R) Protocol and Assessment of Myocardial Infarct Size.42

Mice were fully anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg), intubated, and connected to a rodent ventilator. A median sternotomy was performed to gain access to and identify the left coronary artery (LCA). The LCA was surgically ligated with a 7-0 silk suture mated to a BV-1 needle to ensnare the LCA. A short segment of PE-10 tubing was placed between the LCA and the 7-0 suture to cushion the artery against trauma. Mice were subjected to 45 minutes of LCA ischemia, followed by reperfusion for 24 hours. At 22.5 minutes of ischemia, a single dose of intracardiac injection (50 μL total volume administered with a 31-gauge needle directly into the left ventricular lumen via injection at the apex of the heart) of compound 8a, compound 8l or vehicle (0.5% THF mixed with saline) was administered. After 24 hours of reperfusion, mice were anesthetized and connected to a rodent ventilator. The LCA was religated at the same place as the previous day, and a catheter was placed inside the carotid artery to inject 7.0% Evans blue (1.2 mL) to delineate between ischemic and nonischemic zones. The heart was rapidly excised and cross-sectioned into 1-mm-thick sections, which were then incubated in 1.0% m/v 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride for 4 minutes to demarcate the viable and nonviable myocardium within the risk zone. Digital images of each side of heart section were taken and weighed, and the myocardial area-at-risk and infarct per left ventricle were determined by a blinded observer.

Cardiac Troponin-I Assay.42

Blood samples were collected via a tail vein at 4 h of reperfusion. Cardiac troponin-I level was measured in serum using the Life Diagnostic high-sensitivity mouse cardiac troponin-I ELISA kit (Mouse Cardiac Tn-I ELISA Kit; Life Diagnostics, West Chester, PA) as previously described.

In vivo H2S levels determination

H2S levels were measured according to previously described gas chromatography and chemiliuminesence methods.40 Myocardial tissue or blood were homogenized in 5 volumes of PBS (pH 7.4). 0.2 mL of the sample homogenate was placed in a small glass vial along with 0.4 mL of 1 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and sealed. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min with shaking at 125 rpm on a rotary shaker to facilitate the release of H2S gas from the aqueous phase. After shaking, 0.1 mL of head-space gas was applied to a gas chromatograph (7890A GC, Agilent) equipped with a dual plasma controller and chemiluminescence sulfur detector (355, Agilent). H2S concentrations were calculated using a standard curve of Na2S as a source of H2S. Chromatographs were captured and analyzed with Agilent ChemStation software (B.04.03).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an American Chemical Society-Teva USA Scholar Grant to M.X. and NIH (R01GM088226 to M.X. and R01HL092141, R01HL093579, R01HL079040, P20HL113452, and 5U24HL094373 to D.J.L.). D.J.L. is also supported by the Carlyle Fraser Heart Center of Emory University Hospital Midtown. The authors would like to acknowledge the expert assistance of A. L. King during the course of these experimental studies.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org .

References

- 1.Vandiver MS, Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide: a gasotransmitter of clinical relevance. J Mol Med. 2012;90:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0873-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L, Moore PK. H2S and cell signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:169–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuto JM, Carrington SJ, Tantillo DJ, Harrison JG, Ignarro LJ, Freeman BA, Chen A, Wink DA. Small molecule signaling agents: the integrated chemistry and biochemistry of nitrogen oxides, oxides of carbon, dioxygen, hydrogen sulfide, and their derived species. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:769–793. doi: 10.1021/tx2005234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson KR, Donald JA, Dombkowski RA, Perry SF. Evolutionary and comparative aspects of nitric oxide, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;184:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson KR. A practical look at the chemistry and biology of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2012;17:32–44. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Gojon G. Hydrogen sulfide in biochemistry and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2012;17:119–140. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura H, Shibuya N, Kimura Y. Hydrogen sulfide is a signaling molecule and a cytoprotectant. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2012;17:45–57. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stipanuk MH, Ueki I. Dealing with methionine/homocysteine sulfur: cysteine metabolism to taurine and inorganic sulfur. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:17–32. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filipovic MR, Miljkovic JL, Nauser T, Royzen M, Klos K, Shubina T, Koppenol WH, Lippard SJ, Ivanović-Burmazović I. Chemical characterization of the smallest S-nitrosothiol, HSNO; cellular cross-talk of H2S and S-nitrosothiols. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12016–12027. doi: 10.1021/ja3009693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes MN, Centelles MN, Moore PK. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: The chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caliendo G, Cirino G, Santagada V, Wallace JL. Synthesis and biological effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S): development of H2S-releasing drugs as pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6275–6286. doi: 10.1021/jm901638j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashfi K, Olson KR. Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:689–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeon ER, Stoy GF, Olson KR. Passive loss of hydrogen sulfide in biological experiments. Anal Biochem. 2012;421:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvert JW, Coetzee WA, Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide--mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2010;12:1203–1217. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM, Doeller JE, Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Predmore BL, Kondo K, Bhushan S, Zlatopolsky MA, King AL, Aragon JP, Grinsfelder DB, Condit ME, Lefer DJ. The polysulfide diallyl trisulfide protects the ischemic myocardium by preservation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and increasing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2410–H2418. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00044.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee SW, Zhao Y, Baskar R, Tan CH, Moore PK. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008;117:2351–2360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robison H, Wray S. A new slow releasing, H2S generating compound, GYY4137 relaxes spontaneous and oxytocin-stimulated contractions of human and rat pregnant myometrium. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merighi S, Gessi S, Varani K, Fazzi D, Borea PA. Hydrogen sulfide modulates the release of nitric oxide and VEGF in human keratinocytes. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whiteman M, Li L, Rose P, Tan CH, Parkinson DB, Moore PK. The effect of hydrogen sulfide donors on lipopolysaccharide-induced formation of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2010;12:1147–1154. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Fox B, Keeble J, Salto-Tellez M, Winyard PG, Wood ME, Moore PK, Whiteman M. The complex effects of the slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor GYY4137 in a model of acute joint inflammation and in human cartilage cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2013 Jan 28; doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Salto-Tellez M, Tan CH, Whiteman M, Moore PK. GYY4137, a novel hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule, protects against endotoxic shock in the rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee ZW, Zhou J, Chen CS, Zhao Y, Tan CH, Li L, Moore PK, Deng LW. The slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor, GYY4137, exhibits novel anti-cancer effects in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Wang H, Xian M. Cysteine-activated hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15–17. doi: 10.1021/ja1085723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stipanuk MH, Beck PW. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem J. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francoleon NE, Carrington SJ, Fukuto JM. The reaction of H(2)S with oxidized thiols: generation of persulfides and implications to H(2)S biology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;516:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith DJ, Venkatraghavan V. Synthesis and stability of thiocysteine. Synth Commun. 1985;15:945–950. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heimer NE, Field L, Neal RA. Biologically oriented organic sulfur chemistry. 21. Hydrodisulfide of a penicillamine derivative and related compounds. J Org Chem. 1981;46:1374–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 31.It should be noted that thioacids can be H2S donors in the presence of bicarbonate. See Zhou Z, von Wantoch Rekowski M, Coletta C, Szabo C, Bucci M, Cirino G, Topouzis S, Papapetropoulos A, Giannis A. Thioglycine and L-thiovaline: biologically active H2S-donors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:2675–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.028.

- 32.Mueller EG. Trafficking in persulfides: delivering sulfur in biosynthetic pathways. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nchembio779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King AL, Lefer DJ. Cytoprotective actions of hydrogen sulfide in ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:840–846. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.059725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calvert JW, Elston M, Nicholson CK, Gundewar S, Jha S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Lefer DJ. Genetic and pharmacologic hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates ischemia-induced heart failure in mice. Circulation. 2010;122:11–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.920991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bian JS, Yong QC, Pan TT, Feng ZN, Ali MY, Zhou S, Moore PK. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the cardioprotection caused by ischemic preconditioning in the rat heart and cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:670–678. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, Szabo C, Kimura H, Chow CW, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivarajah A, Collino M, Yasin M, Benetti E, Gallicchio M, Mazzon E, Cuzzocrea S, Fantozzi R, Thiemermann C. Anti-apoptotic and antiinflammatory effects of hydrogen sulfide in a rat model of regional myocardial I/R. Shock. 2009;31:267–274. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180ff89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qipshidze N, Metreveli N, Mishra PK, Lominadze D, Tyagi SC. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates cardiac remodeling during myocardial infarction via improvement of angiogenesis. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:430–441. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Pan J, Li S, Zhao Y, Wu LY, Berkman CE, Whorton AR, Xian M. Capture and visualization of hydrogen sulfide by a fluorescent probe. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:10327–10329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104305. The probe reported in this paper is now commercially available as ‘WSP-1’ by Cayman Chemical Co. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ubuka T, Abe T, Kajikawa R, Morino K. Determination of hydrogen sulfide and acid-labile sulfur in animal tissues by gas chromatography and ion chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2001;757:31–33. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kondo K, Bhushan S, King AL, Prabhu SD, Hamid T, Koenig S, Murohara T, Predmore BL, Gojon G, Sr, Gojon G, Jr, Wang R, Karusula N, Nicholson CK, Calvert JW, Lefer DJ. H2S protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2013;127:1116–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhushan S, Kondo K, Predmore PL, Zlatopolsky M, King AL, Pearce C, Huang H, Tao YX, Condit ME, Lefer DJ. Selective β2-adrenoreceptor stimulation attenuates myocardial cell death and preserves cardiac function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1865–1874. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.251769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.