Abstract

Context

The proportion of US deaths occurring in nursing homes (NHs) has been increasing in the last two decades and is expected to reach 40% by 2020. Despite being recognized as an important setting in the provision of end-of-life care (EOL), little is known about the quality of care provided to dying NH residents. There has been some, but largely anecdotal evidence suggesting that many US NHs transfer dying residents to hospitals, in part to avoid incurring the cost of providing intensive on-site care, and in part because they lack resources to appropriately serve the dying residents. We assessed longitudinal trends and geographic variations in place of death among NH residents, and examined the association between residents’ characteristics, treatment preferences, and the probability of dying in hospitals.

Methods

We used the Minimum Data Set (NH assessment records), Medicare denominator (eligibility) file, and Medicare inpatient and hospice claims to identify decedent NH residents. In CY2003–2007, there were 2,992,261 Medicare eligible nursing home decedents from 16,872 US Medicare and/or Medicaid certified NHs. Our outcome of interest was death in NH or in a hospital. The analytical strategy included descriptive analyses and multiple logistic regression models, with facility fixed effects, to examine risk-adjusted temporal trends in place of death.

Findings

Slightly over 20% of decedent NH residents died in hospitals each year. Controlling for individual level risk factors and for facility fixed effects, the likelihood of residents dying in hospitals has increased significantly each year between 2003 through 2007.

Conclusions

This study fills a significant gap in the current literature on EOL care in US nursing homes by identifying frequent facility-to-hospital transfers and an increasing trend of in-hospital deaths. These findings suggest a need to rethink how best to provide care to EOL nursing home residents.

Keywords: nursing homes, place of death, hospitalization

INTRODUCTION

Nursing homes have been recognized as an important setting for end-of-life (EOL) care. The proportion of US deaths occurring following admission to a nursing home has increased, from 16.0% in 19901 to 25.0% in 20012. As Baby Boomers continue to age this proportion has been projected to grow to 40% by 20203. While quality of care in nursing homes has received much attention from policy makers and researchers alike, there has been less recognition that in the period preceding death residents’ care needs may be quite different from the needs of other residents. Consequently, little is known about the quality of EOL care in this setting4,5.

One area of concern with nursing home quality of care in general has been the frequency with which residents are hospitalized. Nationally, over 25% of short-term (Medicare post-acute) nursing home residents were re-hospitalized within 30 days of discharge to a nursing home, with hospitalization rates ranging from 17% in Vermont to 32.1% in Maryland6. Annual hospitalization rates for long-term nursing home residents have been reported at 17.4% nationally, ranging from 8.4% in Utah to 24.9% in Louisiana7. Prior research has shown that such hospitalizations are costly8 and that many may be inappropriate, leading to adverse health outcomes for the residents9,10. Nursing home residents who are transferred to hospitals often receive unnecessarily aggressive treatment, inconsistent with preferences11, and many die there.

For the most part, however, US-based studies on the site of death, and specifically on EOL hospital transfers of nursing home residents, have been largely absent. A study of nursing homes in Germany showed that 58% of residents were hospitalized in the last month before death 12, but it did not report on the site of death. Two Canadian studies examined variations in the site of death among nursing home residents. In British Columbia almost 25% of decedent nursing home residents died in a hospital 13. A study of residents in 60 Manitoba nursing homes showed that 41% were hospitalized in the last 6 months of life and 19% died in a hospital 14.

In the US, although hospital deaths for nursing home residents are often considered a marker for potentially inappropriate care at the EOL9,15,16, research focusing specifically on where nursing home residents die has been largely absent. A handful of studies have suggested that nursing home residents who use hospice are also more likely to have recorded advance directives (ADs), more likely to choose treatment limitations such as do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not hospitalize (DNH)17–19, and consequently experience lower rates of terminal hospitalizations 20. At the same time, anecdotal evidence has suggested that many US nursing homes transfer residents, including those imminently dying, to hospitals in part to avoid incurring the cost of providing intensive on-site care, and in part because they lack clinical expertise and resources to deal with dying patients21. If such a pattern is indeed pervasive and persistent, there are serious policy and ethical implications to consider. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to: 1) investigate the longitudinal trends and geographic variations in place of death among decedent nursing home residents across the US; and 2) examine the association between hospice use, presence of advance directives and the probability of nursing home residents dying in hospitals.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

This was a retrospective, longitudinal study using nation-wide administrative data from the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW), established and supported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CCW contains information on Medicare beneficiaries, derived from multiple data sources and linked by a unique identifier so that records for each individual can be linked across the continuum of services and longitudinally. For this study, a customized CCW dataset was created based on all decedent, Medicare beneficiaries who resided in US Medicare and/or Medicaid certified nursing homes between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2007.

Using the Medicare denominator files, beneficiaries who died during this time period were first identified. The Minimum Data Set (MDS 2.0) was then used to select decedents who died in a nursing home or within 8 days of discharge to a different care setting. The MDS is a federally mandated process for clinical assessment of residents in Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing homes. It contains information on each resident’s health status at admission and at predetermined intervals thereafter, or when health status changes significantly. The MDS data have been found to be both reliable and valid 22. The finder file of decedents with a prior nursing home stay was then used to select all of their MDS assessments, as well as inpatient hospital and hospice claims for all care settings (i.e. nursing home, hospital, other).

Study Population

We identified 2,992,261 decedent Medicare eligible residents who died between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2007, and who resided in US Medicare and/or Medicaid certified nursing homes (n=16,872 facilities). Several exclusions were made. Decedents who were enrolled in a managed care plan in the last month of life were excluded (n=339,477), because information about their hospitalizations would not be complete in the Medicare claims data. We also excluded decedents who did not have any health assessment records in the MDS (n=122,104). Decedents from the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico (n=306) were also excluded. Our final analytical sample consisted of 2,530,374 decedents (84.56% of the total).

Variables

The outcome of interest was death occurring in a nursing home or a hospital, within 8 days of transfer. We chose 8 days based on review of the literature23–25, and also because deaths associated with longer hospitalizations may be the result of circumstances that cannot be attributed to nursing homes, i.e. decedents were truly no longer nursing home residents. We identified deaths as occurring in nursing homes when the MDS discharge type was coded as “deceased” or the decedent’s last MDS record was a “reentry.” Deaths were defined as occurring in a hospital when the date of death overlapped with a hospital stay, discharge from a nursing home to a hospital or with a hospital-based hospice stay, immediately following a hospitalization event. All remaining deaths occurred outside of nursing homes or hospitals, but there was no way to ascertain exactly where, hence we defined them as “other” and excluded them from the analysis.

Review of the literature served as a guide for identifying resident characteristics likely to influence place of death for nursing home residents. Demographic characteristics included were age at death, gender and race/ethnicity. Both age and race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, other) were defined as categorical variables. To account for differences in the decedents’ health status, dummy variables were included for the following chronic conditions: diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancer, Alzheimer’s, and renal failure. Decedents were further classified as short-term (rehabilitative/post-acute care) if they stayed in a nursing home for less than 90 days and had only Medicare-type assessments. Otherwise they were classified as long-term (custodial care) residents. Residents’ chronic conditions and presence of specific advance directives (DNR and DNH) were identified from their last full MDS assessment. A decedent was considered to be a hospice user if s/he had claims for hospice services provided in the nursing home in the last 30 days of life.

Analyses

The associations between the independent variables and the site of death were first assessed in a bivariate analysis using chi-square statistics. Crude proportions of residents by place of death and by year were calculated for all decedents and for long and short-term residents separately. We fit fractional polynomial models with these proportions as the dependent variables, and the year of death as a continuous independent variable, to depict these trends graphically. We also examined the geographic variation in the proportion of residents dying in hospitals across all states. The proportions of state-level in-hospital deaths were categorized into four quartiles and graphed on a national map.

In order to examine adjusted, temporal trends in hospital deaths, we fit logistic models with facility fixed effects (to control for time-invariant facility-level variables), and included the year of death, demographic and health status characteristics, hospice use in the last 30 days of life, and presence of DNR and DNH orders. The analyses were performed separately for long and short-term residents. C-statistics were calculated, to assess the predictive power of each model. For each model, we also tested the difference in the year of death effect comparing each year to a prior year.

To identify possible disparate longitudinal trends for hospice users and non-users, we repeated the analyses adding interaction terms between hospice status and year dummies. Based on the estimated coefficients, we predicted the risk of in-hospital death for each group --- hospice users and non-users --- for each year, given average sample characteristics. We then compared the predicted risk of in-hospital death both within and across these groups. Within each group, we compared the risk in each year to a preceding year. Across groups, we examined the interaction terms to test for the significance of the differences in changes between consecutive years. All standard errors (and thus p-values) were calculated using the delta method, an approximation appropriate in large samples. The introduction of the interaction terms changed the estimators for covariates very slightly. Therefore, we only presented the predicted risks and p-values for the comparisons between and across groups of hospice users and non-users. Full model estimation results are available upon request.

RESULTS

Of the over 2.5 million deaths that occurred among nursing home residents in the US between 2003 and 2007, 20.44% (n=517,186) occurred in hospitals (Table 1). Residents dying in hospitals were younger; 27.98% of individuals younger than 65 died in hospitals compared to 17.70% of those age 85 and older. Males were somewhat more likely to die in hospitals (22.44%) compared to females (19.30%). Blacks and Hispanics were considerably more likely to die in hospitals (28.05% and 27.15%, respectively) compared to Whites (19.49%). We found short-term residents more likely to die in hospitals (25.39%) compared to long-term residents (17.35%). Those with cancer and Alzheimer’s were less likely to die in a hospital compared to residents without these conditions (15.24% vs. 20.44% for cancer and 14.41% vs. 20.68% for Alzheimer’s, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Decedent Nursing Home Residents, CY2003–2007

| Nursing Home Deaths | Hospital Deaths | All Other Deaths | Total Deaths | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Characteristics | 1,752,621 | 69.26 | 517,186 | 20.44 | 260,567 | 10.30 | 2,530,374 | |

| Year of death | ||||||||

| 2003 | 349,759 | 70.13 | 102,619 | 20.58 | 46,338 | 9.29 | 498,716 | <.0001 |

| 2004 | 364,986 | 69.86 | 107,129 | 20.50 | 50,350 | 9.64 | 522,465 | |

| 2005 | 369,957 | 69.16 | 109,601 | 20.49 | 55,333 | 10.34 | 534,891 | |

| 2006 | 347,132 | 68.93 | 102,419 | 20.34 | 54,061 | 10.73 | 503,612 | |

| 2007 | 320,787 | 68.15 | 95,418 | 20.27 | 54,485 | 11.58 | 470,690 | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age at death | <.0001 | |||||||

| Younger than 65 | 53,383 | 58.81 | 25,397 | 27.98 | 11,993 | 13.21 | 90,773 | |

| 65 – 74 | 168,287 | 61.36 | 70,227 | 25.61 | 35,726 | 13.03 | 274,240 | |

| 75 – 84 | 470,025 | 65.62 | 165,134 | 23.05 | 81,139 | 11.33 | 716,298 | |

| 85+ | 1,060,926 | 73.21 | 256,428 | 17.70 | 131,709 | 9.09 | 1,449,063 | |

| Gender | <.0001 | |||||||

| Male | 605,610 | 66.10 | 205,632 | 22.44 | 104,975 | 11.46 | 916,217 | |

| Female | 1,147,011 | 71.06 | 311,554 | 19.30 | 155,592 | 9.64 | 1,614,157 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | |||||||

| White | 1,560,447 | 70.43 | 431,737 | 19.49 | 223,459 | 10.09 | 2,215,643 | |

| Black | 128,242 | 60.76 | 59,204 | 28.05 | 23,601 | 11.18 | 211,047 | |

| Hispanic | 36,397 | 59.24 | 16,683 | 27.15 | 8,365 | 13.61 | 61,445 | |

| Other | 27,535 | 65.19 | 9,562 | 22.64 | 5,142 | 12.17 | 42,239 | |

| Health characteristics | <.0001 | |||||||

| Residency type | ||||||||

| Custodial care | 1,159,709 | 74.47 | 270,145 | 17.35 | 127,400 | 8.18 | 1,557,254 | |

| Rehabilitative care | 592,912 | 60.93 | 247,041 | 25.39 | 133,167 | 13.68 | 973,120 | |

| Diabetesa | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 430,836 | 66.06 | 153,054 | 23.47 | 68,310 | 10.47 | 652,200 | |

| No | 1,141,603 | 72.38 | 283,920 | 18.00 | 151,646 | 9.62 | 1,577,169 | |

| Congestive heart failurea | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 498,654 | 68.41 | 158,750 | 21.78 | 71,518 | 9.81 | 728,922 | |

| No | 1,073,785 | 71.56 | 278,224 | 18.54 | 148,438 | 9.89 | 1,500,447 | |

| Cancera | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 259,078 | 72.24 | 54,651 | 15.24 | 44,891 | 12.52 | 358,620 | |

| No | 1,313,361 | 70.21 | 382,323 | 20.44 | 175,065 | 9.36 | 1,870,749 | |

| COPDa | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 348,462 | 66.96 | 118,109 | 22.69 | 53,864 | 10.35 | 520,435 | |

| No | 1,223,977 | 71.62 | 318,865 | 18.66 | 166,092 | 9.72 | 1,708,934 | |

| Alzheimera | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 298,863 | 77.76 | 55,377 | 14.41 | 30,115 | 7.84 | 384,355 | |

| No | 1,273,576 | 69.03 | 381,597 | 20.68 | 189,841 | 10.29 | 1,845,014 | |

| Renal failurea | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 174,136 | 65.19 | 63,599 | 23.81 | 29,370 | 11.00 | 267,105 | |

| No | 1,398,303 | 71.26 | 373,375 | 19.03 | 190,586 | 9.71 | 1,962,264 | |

| Treatment preferences | ||||||||

| DNR orderb | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 1,123,966 | 77.47 | 202,714 | 13.97 | 124,101 | 8.55 | 1,450,781 | |

| No | 428,805 | 57.44 | 226,070 | 30.28 | 91,666 | 12.28 | 746,541 | |

| DNH orderb | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 118,743 | 88.22 | 6,145 | 4.57 | 9,708 | 7.21 | 134,596 | |

| No | 1,434,028 | 69.52 | 422,639 | 20.49 | 206,059 | 9.99 | 2,062,726 | |

| Hospice in the last 30 days of life | <.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 564,500 | 85.94 | 15,396 | 2.34 | 76,927 | 11.71 | 656,823 | |

| No | 1,188,121 | 63.42 | 501,790 | 26.78 | 183,640 | 9.80 | 1,873,551 | |

301,005 people are missing this variable

333,052 people are missing this variable

We observed significant differences in place of death with presence of specific advance directives. Residents with a recorded DNR order were less likely to die in hospitals compared to those without (13.97% vs. 30.28%). Similarly, residents with DNH orders were much less likely (4.57%) to die in hospitals compared to residents without such orders (20.49%). Furthermore, residents who received hospice care in the last 30 days of life, were also less likely to die in a hospital (2.34%) compared to those who did not receive hospice (26.78%).

Each year, between 2003 and 2007, one third of nursing home decedent residents, were hospitalized in the last 30 days of life. In 2007, these hospitalizations cost Medicare almost $1.6 billion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospitalizations and Medicare costs: nursing home decedent residents, 2003–2007

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | PCT | Number | PCT | Number | PCT | Number | PCT | Number | PCT | |

| Nursing home decedent residents hospitalized in the last 30 days of life | ||||||||||

| Short-stay | 65,559 | 31.6% | 64,654 | 33.0% | 68,759 | 34.1% | 67,442 | 35.4% | 65,561 | 36.8% |

| Long-stay | 93,697 | 32.2% | 109,675 | 33.6% | 111,994 | 33.6% | 104,065 | 33.2% | 97,836 | 33.4% |

| Total | 159,256 | 31.9% | 174,329 | 33.4% | 180,753 | 33.8% | 171,507 | 34.1% | 163,397 | 34.7% |

| Total cost of hospitalizations in last 30 days of life ($2007) | ||||||||||

| Short-stay | $631,903,448 | 42.6% | $617,859,933 | 38.0% | $671,877,569 | 39.1% | $662,443,943 | 40.4% | $647,997,581 | 40.7% |

| Long-stay | $849,903,942 | 57.4% | $1,009,457,774 | 62.0% | $1,047,543,540 | 60.9% | $976,035,938 | 59.6% | $943,591,293 | 59.3% |

| Total | $1,481,807,390 | 100.0% | $1,627,317,707 | 100.0% | $1,719,421,109 | 100.0% | $1,638,479,881 | 100.0% | $1,591,588,874 | 100.0% |

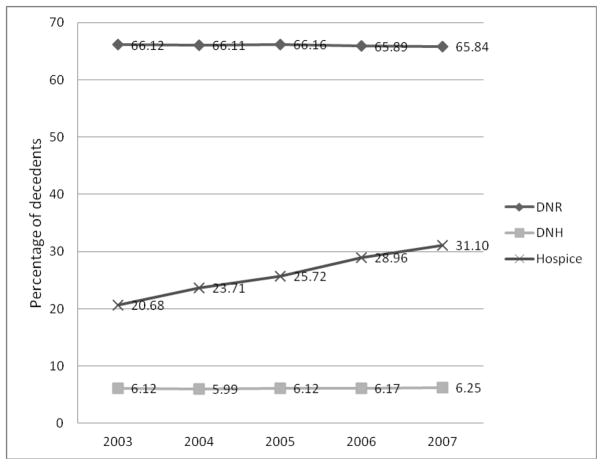

Longitudinal trends and geographic variations in place of death

Over the five-year period examined, the unadjusted proportion of in-hospital deaths did not appear to have changed much, fluctuating on average within 1% for all decedents, as well as for both the long and the short-stay residents (Figure 1: a–c). The raw proportion of nursing home deaths has changed only slightly, declining by 2 percentage points from 2003 to 2007 (Figure 1: d). The bulk of this decline has occurred among short-term nursing home residents, who were 8.5% less likely to die in nursing homes in 2007 (58.35%) than in 2003 (63.30%) (Figure 1: f).

Figure 1.

Percent of deaths occurring in hospitals and nursing homes –all decedents, long and short stay: CY2003–2007

The dots represent the percentage of deaths that occurred either in hospitals or nursing homes each year. The curved line represents the temporal trend in the percentage of deaths, estimated by the best fitting fractional polynomial model. The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval.

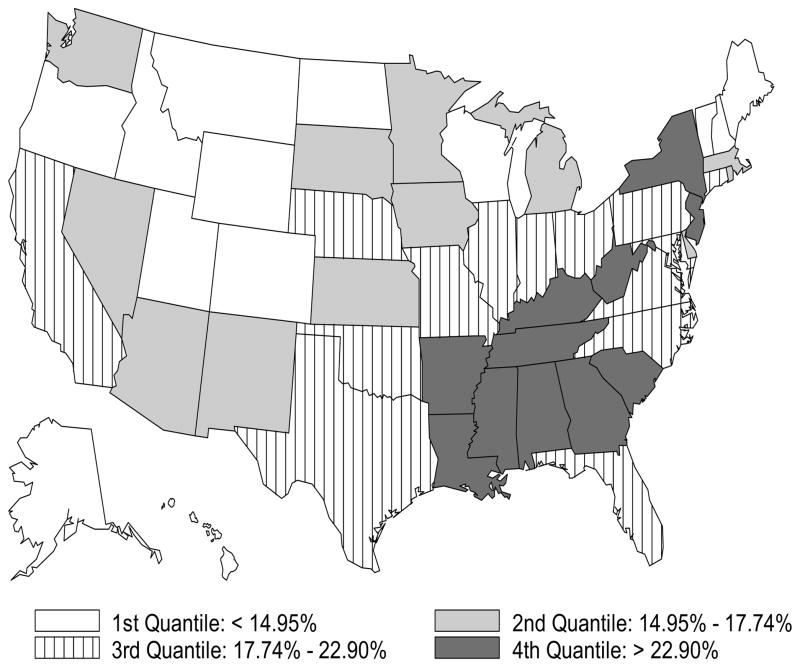

During this time period, there was a significant annual increase in the use of hospice at the EOL (Figure 2). While in 2003, 1 in 5 decedent nursing home residents used hospice in the last 30 days of life, by 2007 1 in 3 (31.10%) had hospice care, a 50% increase over a 5-year period. Although hospice selection is typically assumed to be associated with residents’ also selecting DNR and DNH orders, we did not observe a similar trend as the proportions of residents with these advance directives has remained unchanged over time.

Figure 2.

Percent of decedent nursing home residents with DNR and DNH orders and using hospice in the last 30 days of life: CY2003–2007

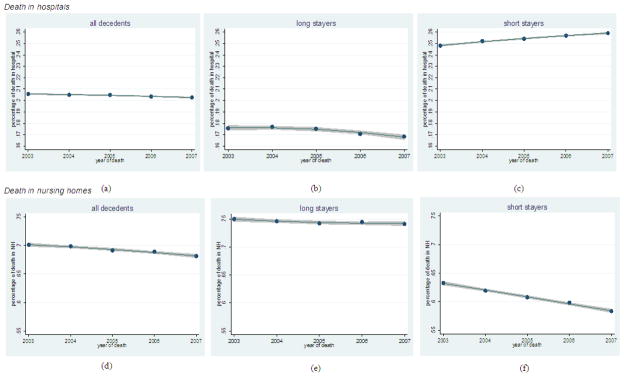

The distribution of in-hospital deaths among nursing home residents varied quite substantially across states (Figure 3). States in the lowest two quartiles of in-hospital deaths (<=17.74%) were located largely in the Mid West and the North East of the country. Southern states, as well as New York and New Jersey, had the highest concentration of in-hospital death (>22.90%). These across-state variations have remained very stable between CY2003–2007 (not depicted here).

Figure 3.

Distribution of in-hospital deaths among decedent nursing home residents, by state (CY2003–2007)

Association between hospice use, advance directives, and in-hospital deaths

We fit multiple logistic regression models with facility fixed effects to examine the adjusted probability of nursing home residents dying in hospitals, over time. The C statistics for these models were 0.73 for the long-stay residents and 0.69 for the short stay, indicating moderate predictive values of these models. For both long and short-stay residents there was a statistically significant annual increase in the likelihood of dying in a hospital between CY2003 and 2007 (Table 2). Compared to the reference year (2003), the odds ratios for in-hospital deaths among long-stay residents were 1.078, 1.112, 1.141, and 1.162 in each subsequent year, all else being equal. We observed a similar pattern for short-stay residents with odds ratios of 1.051, 1.088, 1.125, and 1.171 in 2004 through 2007, respectively. Furthermore, the incremental annual change in the likelihood of in-hospital deaths was also statistically significant (p<0.05) from one year to another, for both short and long-stay residents.

Consistent with prior research, we found older residents, in both short and long-stay groups, to have lower odds of in-hospital death. For example, compared to residents younger than age 65, older long-stay residents had progressively lower odds for dying in a hospital (OR=0.922, 0.903, 0.725 for residents age 65–74, 75–84, and 85 and older, respectively). Compared to white (reference) long-stay residents, the odds of in-hospital deaths were not statistically different for blacks, but were 11% (OR=1.111) higher among Hispanics. Among short-stay residents, blacks were slightly less likely (OR=0.962) than whites to die in a hospital, but Hispanics were considerably more likely (OR=1.168) to do so. Both short and long-stay residents with cancer and Alzheimer’s were less likely to die in a hospital than residents without these conditions.

Treatment preferences such as hospice use and presence of DNR and DNH orders appeared to have had a profound impact on in-hospital deaths among both long and short-stay decedent residents. Having a DNR order reduced the odds of in-hospital deaths by 45.4% and 53.7%, for long and short-stay residents respectively, while having a DNH order reduced the odds of in-hospital deaths by 69.0% and 77.4%, respectively. Among residents who used hospice services in the last 30 days of life, the odds of in-hospital deaths were very small (OR=0.046 and OR=0.070) for long and short-stay groups respectively.

To better understand the extent to which the observed temporal increase in in-hospital deaths may have been due to the increase in hospice use, and the selection process that may have accompanied it, we further examined the adjusted risk of in-hospital deaths by hospice status and year of death (Table 3). For the non-users of hospice services we observed a statistically significant annual increase in the adjusted predicted risk of in-hospital deaths from CY2003 through CY2007 for both short and long-stay decedent residents. For hospice users, our findings are mixed and overall largely not statistically significant. Furthermore, for long-stay residents, the difference in the predicted risk of in-hospital death between hospice users and non-users was statistically significant, except in CY2004, while for short-stay residents the difference was not statistically significant, except in CY2007.

Table 3.

Likelihood of decedent nursing home residents dying in hospital, CY2003–2007: Stratified by long vs. short stay

| Independent variables | Long-stay Residents (n=1,461,123) | Short-stay Residents (n=724,816) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Odds Ratio | 95%CI | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | |||

| Year of death (ref = 2003)$ | ||||||

| 2004 | 1.078 | 1.061 | 1.095 | 1.051 | 1.032 | 1.071 |

| 2005 | 1.112 | 1.094 | 1.129 | 1.088 | 1.068 | 1.108 |

| 2006 | 1.141 | 1.122 | 1.159 | 1.125 | 1.104 | 1.146 |

| 2007 | 1.162 | 1.143 | 1.182 | 1.171 | 1.148 | 1.194 |

| Age (ref= < 65) | ||||||

| 65–74 | 0.922 | 0.897 | 0.947 | 0.979 | 0.947 | 1.013 |

| 75–84 | 0.903 | 0.881 | 0.926 | 0.946 | 0.917 | 0.976 |

| 85 and older | 0.725 | 0.708 | 0.744 | 0.783 | 0.759 | 0.809 |

| Gender (ref=female) | ||||||

| Male | 1.097 | 1.086 | 1.109 | 0.954 | 0.943 | 0.966 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref =white) | ||||||

| Black | 0.995 | 0.977 | 1.013 | 0.962 | 0.938 | 0.986 |

| Hispanic | 1.111 | 1.075 | 1.149 | 1.168 | 1.118 | 1.221 |

| Other | 0.875 | 0.839 | 0.911 | 1.033 | 0.982 | 1.087 |

| Diseases | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.180 | 1.168 | 1.192 | 1.082 | 1.068 | 1.096 |

| Cancer | 0.823 | 0.810 | 0.836 | 0.708 | 0.697 | 0.719 |

| COPD | 1.158 | 1.145 | 1.172 | 1.144 | 1.128 | 1.159 |

| CHF | 1.138 | 1.127 | 1.150 | 1.110 | 1.096 | 1.124 |

| Alzheimer | 0.758 | 0.748 | 0.768 | 0.755 | 0.738 | 0.772 |

| Renal failure | 1.101 | 1.084 | 1.118 | 1.077 | 1.060 | 1.095 |

| Treatment preferences | ||||||

| Hospice | 0.046 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.070 | 0.068 | 0.072 |

| DNR | 0.546 | 0.540 | 0.552 | 0.463 | 0.456 | 0.469 |

| DNH | 0.310 | 0.300 | 0.321 | 0.226 | 0.215 | 0.239 |

| C-statistics | 0.73 | 0.69 | ||||

note: facility fixed effect not shown

p-values of year effect are calculated based on comparison between each year and its previous year p>0.05, i.e. not significant

DISCUSSION

It has been said that the truest test of any society is the way it treats its most vulnerable members. In much the same way, the true test of a nursing home may be how it treats residents at the EOL. By and large, the literature suggests that nursing home residents typically hope to avoid being hospitalized 26, particularly at the EOL when such transfers are distressing to both the residents and their families 26–28, and result in poor outcomes such as disorientation or delirium and hastened functional and cognitive decline 29,30.

Regardless of such negative consequences of nursing home-to-hospital transfers, our findings demonstrate that, in the US, each year 35% of decedent nursing home residents are hospitalized in the last 30 days of life, at an annual Medicare cost of more than $1.6 billion dollars. As a consequence of these frequent hospitalizations, 1 in 5 nursing home residents die in hospitals. However, this practice is not uniform across the country. There is substantial variation across both states and facilities, suggesting room for improvement.

Although individual risk factors are important in influencing the probability of in-hospital deaths, the health care system also presents sometimes quite formidable obstacles for nursing home residents who may wish to avoid being hospitalized at the EOL. State nursing home regulations, for example in New York State, and in other states, require residents to be transferred to a hospital when such transfer is “medically appropriate,” but the law neither defines medical appropriateness nor provides guidelines for its interpretation. Medical directors and nursing home administrators may prefer to apply this definition quite liberally to avoid deficiency citations, allegations of patient neglect, or lawsuits 26,31. In fact, inhospital death rates are among the highest (top quartile) in the nation for New York nursing home residents (see Figure 3); in 2007 the average rate of in-hospital deaths was 26.7%, ranging from 9.3% to 50.0% in the lowest and highest deciles of facilities, respectively. Furthermore, both Medicare and Medicaid financial reimbursement policies provide additional incentives to nursing homes to hospitalize their residents 32. Nursing homes often lack adequate clinical infrastructure to care for the acutely ill residents. Thus hospitalizing residents and shifting costs to a hospital setting (Medicare) is beneficial to nursing homes, even if it is not to their residents. Medicaid nursing home payment rates, case-mix adjusted reimbursement and “bed hold” policies also have been shown to incentivize facilities to hospitalize their Medicaid residents, including at the EOL 6,33,34.

Consistent with studies showing a significant increase in the use of nursing home hospice 35, our findings demonstrated a 50% increase, from 2003-to-2007, in the proportion of decedent nursing home residents using hospice care in the last 30 days of life. Not surprisingly, residents who used nursing home hospice had much lower odds of dying in a hospital compared to those who either did not elect or were not offered hospice care. However, the increase in the use of hospice did not appear to stem the significant temporal increase, we observed, in the likelihood of nursing home residents’ dying in hospitals. Controlling for individual-level risk factors and for facility fixed effects, the odds of nursing home residents dying in hospitals has increased significantly each year from 2003 through 2007, for short stay and long-stay residents. Although different in magnitude, the predicted risk of in-hospital death has increased each year for hospice users and non-users alike.

It is not immediately clear what accounts for this observed increase in the risk of in-hospital deaths for nursing home residents. Several factors may be at play. First, the rate of skilled nursing facility re-hospitalizations has been reported to have increased by 29% from 2000 to 2006 6. It is possible that this increase in re-hospitalizations has “spilled-over” to the overall nursing home population, including those at the EOL. Second, since 2000 states have been generally rebalancing their economic resources from nursing homes to community-based long-term care programs, a trend that has resulted in a reported 25% reduction in Medicaid spending on nursing facility services 36. As a consequence, the incentive for nursing homes to hospitalize residents when faced with higher care costs would likely also increase. Third, although the proportion of people dying in nursing homes has been increasing 37, nursing homes’ investment in EOL care remains quite marginal. A recent national study showed that only 17% of nursing homes reported special program trained staff for palliative/end-of-life care, and only 19% reported such staff training for hospice care 38. Furthermore, it appears that law suits against nursing homes, largely by residents’ family members, represent the fastest growing area of healthcare litigations39. Perhaps as a result, nursing home physicians and facilities concerned with liability issues31 may have become increasingly more inclined to hospitalize residents at the end-of-life, thus increasing the likelihood of inhospital death. In face of these trends, the ethical concern about not abandoning dying nursing home residents may have, ironically, resulted in the observed increase in nursing home-to-hospital transfers.

Several limitations of the study should be mentioned. First, our focus on in-hospital death implicitly assumes that this outcome is less desirable than death in a nursing home. If, however, a nursing home is not able to manage symptoms and provide quality palliative care, hospital admission may be preferable. Second, we did not examine the reasons for the hospitalizations of nursing home residents that have resulted in death, and thus we did not distinguish between “inappropriate” and potentially “appropriate” transfers. Last, although we adjusted for the demographic, health, and treatment preferences of the decedents and used facility fixed effects to control for time-invariant factors that might affect in hospital deaths, some unobservable factors (including diagnoses that may be under-reported) may bias the results.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study fills a significant gap in the current literature on EOL care in nursing homes in the United States, by identifying frequent facility-to-hospital transfers and an increasing trend of inhospital deaths in this population. Prior literature has demonstrated that with appropriate resources it is often more medically desirable, and for nursing home residents also preferable, to avoid in-hospital death. Today, the primary mechanism for funding and delivering end-of-life care to nursing home residents is through hospice enrollment. There are several features of the Medicare hospice eligibility, coverage and reimbursement that appear to limit a broad-based expansion of this service for nursing home residents 35. Recently two proposals for restructuring EOL care delivery and financing in nursing homes have been advanced, both proposing to incorporate end-of-life/palliative care for all nursing home residents, designed to pay nursing homes directly for such care and holding them accountable for the quality of EOL care they provide 40,41. Models integrating end-of-life/palliative care with other nursing home services may indeed hold promise for improving EOL quality of care for residents. Although CMS routinely evaluate and publically report on quality of care in nursing homes based on 19 quality indicators, none of these measures focuses on quality of EOL care. Risk-adjusted EOL measures for nursing homes have recently been proposed16, and if they become part of the nursing home report cards, they may further focus the much needed attention on EOL and its quality of care.

By 2030, nearly half of all Americans age 85 and older will live and die in nursing homes (Christopher, 2000). It is none too soon to consider a paradigm shift in nursing home policy, regulation and investment in EOL care. A more effective provision of on-site medical services to this very vulnerable population of nursing home residents is likely to improve the quality of care and life and perhaps also to stem the growth of Medicare spending.

Table 4.

Adjusted, predicted risk of in-hospital death by hospice status and year of death

| Long stay

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | HOSPICE USERS | HOSPICE NON-USERS | Comparison of Predicted Risk between Hospice Users and Non Users | ||

|

| |||||

| Predicted risk | P-value* | Predicted risk | P-value* | P-value | |

| 2003 | 0.019 | 0.326 | |||

| 2004 | 0.023 | 0.001 | 0.342 | <.001 | 0.063 |

| 2005 | 0.024 | 0.112 | 0.349 | 0.000 | 0.011 |

| 2006 | 0.025 | 0.121 | 0.354 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 2007 | 0.027 | 0.094 | 0.358 | 0.037 | <.001 |

| Short stay

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | HOSPICE USERS | HOSPICE NON-USERS | Comparison of Predicted Risk between HospiceUsers and Non Users | ||

|

| |||||

| Predicted risk | P-value* | Predicted risk | P-value* | P-value | |

| 2003 | 0.032 | 0.329 | |||

| 2004 | 0.034 | 0.317 | 0.340 | <.001 | 0.974 |

| 2005 | 0.035 | 0.249 | 0.347 | <.001 | 0.663 |

| 2006 | 0.037 | 0.456 | 0.355 | <.001 | 0.667 |

| 2007 | 0.041 | 0.008 | 0.363 | <.001 | 0.046 |

Comparison between consecutive years

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant NR010727

The research protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Helena Temkin-Greener, Email: Helena_Temkin-Greener@urmc.rochester.edu, Department of Public Health Sciences, Center for Ethics, Humanities and Palliative Care, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Box 644, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642, (585-275-8713).

Nan Tracy Zheng, RTI International, Suite 310, Waltham.

Jingping Xing, University of Rochester, Department of Public Health Sciences.

Dana B. Mukamel, Department of Medicine, Health Policy Research Institute, University of California, Irvine.

References

- 1.Flory J, Young-Xu Y, Gurol I, Levinsky N, Ash A, Emanuel E. Place of Death: U.S. Trends since 1980. Health Affairs. 2004;23:194–200. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facts on Dying. 2001 (Accessed at http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/FACTSONDYING.HTM)

- 3.Christopher M. Benchmarks to Improve End of Life Care. Midwest Bioethics Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruneir A, Mor V. Nursing Home Safety: Current Issues and Barriers to Improvement. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:369–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker Oliver D, Porock D, Zweig S. End-of-Life Care in U.S. Nursing Homes: A Review of Evidence. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2004;5:147–55. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123063.79715.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski D. The Revolving Door of Rehospitalization From Skilled Nursing Facilities. Health Affairs. 2010;29:57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intrator O, et al. Hospitalizations of nursing home residents: the effects of states’ Medicaid payment and bed-hold policies. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1651–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ, Barhydt NR. The costs and potential savings associated with nursing home hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1753–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saliba D, Kington R, Buchanan J. Appropriateness of the Decision to Transfer Nursing Facility Residents to the Hospital. JAGS. 2000;48:154–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donelan-McCall NET, Fish R, Kramer A. Medicare Payment Advisory C. Washington, DC: 2006. Small patient population and low frequency events effects on the stability of SNF quality measures. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobalian A. Nursing Facility Compliance With Do-Not-Hospitalize Orders. Gerontologist. 2004;44:159–65. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramroth H, Specht-Leible N, Konig HH, Brenner H. Hospitalizations during the last months of life of nursing home residents: a retrospective cohort study from Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:70. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGregor MJ, Tate RB, Ronald LA, McGrail KM. Variation in Site of Death among Nursing Home Residents in British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;10:1128–36. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menec VN, Nowicki S, Blandord A, Veselyuk D. Hospitalizations at the End of Life Ammong Long-Term Care Residents. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2009;64A:395–402. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis SS, Loving G, McClanahan L, Bernard M. Hospitalization Patterns and Palliation in the Last Year of Life Among Residents in Long-Term Care. the Gerontologist. 2001;41:153–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukamel D, Caprio T, Ahn R, et al. End-of-Life Quality of Care Measures for Nursing Homes: Place of Death and Hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15:438–46. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molloy DW, Guyatt GH, Russo R, et al. Systematic Implementation of an Advance Directive Program in Nursing Homes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1437–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice KN, Coleman EA, Fish R, Levy C, Kutner JS. Factors Influencing Models of End-of-Life Care in Nursing Homes: Results of a Survey of Nursing Home Administrators. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2004;7:668–75. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker-Oliver D, Bickel D. Nursing home experience with hospice. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2002;3:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SC, Gozalo P, Mor V. Hospice enrollment and hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Am J Med. 2001;111:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huskamp HA, Buntin MB, Wang V, Newhouse J. Providing Care At the End Of Life: Do Medicare Rules Impede Good Care? Health Affairs. 2001;20:204–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mor V, Berg K, Angelelli J, Gifford D, Morris J, Moore T. The quality of quality measurement in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43(Spec No 2):37–46. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gozalo P, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitaliation of dying nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, Gozalo P, Lapane K. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:507–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozalo P, Teno J, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-Life Transitions among Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1212–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purdy W. Nursing Home to Emergency Room? The Troubling Last Transfer Hastings Cent Rep. 2002;32:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vohra JU, Brazil K, Hanna S, Abelson J. Family perceptions of end-of-life care in long-term care facilities. J Palliative Care. 2004;20:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end of life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman EM, SJ, Chomiak A, Kramer A. Post-hospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Services Research. 2004;39:1449–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, SL, Skinner J, Kuo S, Fisher E, et al. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliative Medicine. 2009;12:359–62. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry M, Cummings J, Jacobson G, Neuman T, Cubanski J. To Hospitalize or Not to Hospitalized: Medical Care for Long-Term Care facility Residents. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desmarais H. Financial Incentives in the Long-Term Care Context: A First Look at Relevant Information. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai S. Hospitalization Risks in Nursing Homes. Does Payer Source Matter? Rochester: University of Rochester; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Intrator OMV. Effect of State Medicaid Reimbursement Rates on Hospitalizations from Nursing Homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:393–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller SLJ, Gozalo PL, Mor V. The Growth of Hospice Care in U.S. Nursing Homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58:1481–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ELJAY LLC. Prepared for the American Health Care Association. Nov, 2009. A Report on the Shortfalls in Medicaid Funding for Nursing Home Care. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weitzen S, Teno JM, Fennell M, Mor V. Factors Associated with Site of Death: A National Study of Where People Die. Medical Care. 2003;41:323–35. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044913.37084.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller SC, Han B. End-of-Life Care in U.S. Nursing Homes: Nursing Homes wtih Special Programs and Trained Staff for Hospice or Palliative/End-of-Life Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11:866–77. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevenson D, Studdert D. The rise of nursing home litigation: findings from a national survey of attorneys. Health Affairs. 2003;2:219–29. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier DE, Lim B, Carlson M. Raising The Standard: Palliative Care in Nursing Homes. Health Affairs. 2010;29:136–40. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huskamp HAS, DG, Chernew ME, Newhouse JP. A New Medicare End-of-Life Benefit for Nursing Home Residents. Health Affairs. 2010;29:130–5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]