Abstract

O-Specific polysaccharides of Brucella contain two antigenic determinants, called A and M. Most of the strains express epitope A with a small amount of epitope M, whereas B. melitensis strain 16M expresses longer polymer consisting mostly of M-type epitopes. Proposed explanation was that epitope A is defined by 1–2-linked homopolymer of N-formylperosamine (Rha4NFo), while epitope M is a pentasaccharide with four 2- and one 3-substituted Rha4NFo. We reinvestigated both types of structures by 2D NMR and showed that M-epitope is a tetrasaccharide, missing one of the 2-linked Rha4NFo as compared to the previously proposed structure. Polysaccharide from B. melitensis 16M contains a fragment of 1–2-lnked polymer, capped with M-type polymer. Other strains contain one or two M-type units at the non-reducing end of the 1–2-linked O-chain.

Keywords: Brucella, LPS, structure, NMR, MS

Brucellae are Gram-negative coccobacilli and facultative intracellular pathogens. They cause animal diseases, transmitted to humans by contact with animals or animal products infected with B. abortus, B. melitensis or B. suis, resulting in acute or chronic disease with non-specific symptoms, difficult to diagnose and treat.1 The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produced by Brucella posses unusual immunological properties such as low toxicity, intensively studied during last years (reviewed in 2). LPS is considered a major virulence factor of Brucella and the whole cell animal vaccines produce high titers of antibodies to it.3,4 Structure of the polysaccharide chain of the LPS was studied for B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis.5–7. In all cases it was a homopolymer of 4-formamido-4,6-dideoxy-D-mannose (N-formylperosamine, Rha4NFo), comprising two antigenic determinants named A (from abortus) and M (from melitensis). Epitope A was defined as polymer of 1–2-linked N-formylperosamine (Rha4NFo), while epitope M was ascribed to the presence of some amount of 1–3-linkages between perosamine residues. The highest concentration of M-epitope was found in the O-chain of B. melitensis strain 16M and the following pentasaccharide repeating unit was suggested for epitope M:8

Strains other than B. melitensis 16B also possesed some amounts of 1–3 linkages but its position remained unclear until now.

We have recently reported the study of the reducing-end fragment of the Brucella O-antigen and its core.9 Here we report the results of the analysis of A and M epitopes.

We analyzed both types of structures in B. suis strain 4, B. abortus biotype 4, B. melitensis strains 3 and 16M by 2D NMR and mass spectrometry (Table 1, Fig. 1–4). Due to the similarity of components of the O-chain NMR spectra contained severe signal overlap. The best spectra were obtained for N-deformylated polysaccharides; N-formyl (native) or N-acetyl-derivatives had too many overlaps of anomeric signals to be reliably analyzed. Sequence assignment was based mostly on proton correlation spectra. Heteronuclear spectra were also used but gave little information because of overlaping signals and low intensity of HMBC signals of unique components of the polymer.

Table 1.

NMR data for N-deformylated polysaccharide from B. melitensis 16M.

| H/C-1 | H/C-2 | H/C-3 | H/C-4 | H/C-5 | H/C-6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rha4N A | 5.29; 5.30 | 4.20 | 4.18 | 3.26 | 4.05 | 1.36 |

| 101.3 | 77.5 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.0 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N C | 5.26 | 4.22 | 4.21 | 3.29 | 4.11 | 1.38 |

| 101.5 | 77.5 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.0 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N D | 5.23 | 4.20 | 4.17 | 3.28 | 4.08 | 1.37 |

| 101.5 | 77.5 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.0 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N E | 5.19 | 4.28 | 4.22 | 3.29 | 4.32 | 1.39 |

| 101.5 | 77.6 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.4 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N G | 5.10; 5.09 | 4.33 | 4.21 | 3.38 | 4.12 | 1.39 |

| 103.0 | 68.9 | 77.5 | 53.3 | 67.0 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N B | 5.26 | 4.25 | 4.20 | 3.29 | 4.30 | 1.39 |

| 101.5 | 78.5 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.4 | 18.0 | |

| Rha4N F | 5.13 | 4.12 | 4.03 | 3.22 | 4.12 | 1.37 |

| 101.5 | 69.6 | 67.1 | 54.9 | 67.0 | 18.0 |

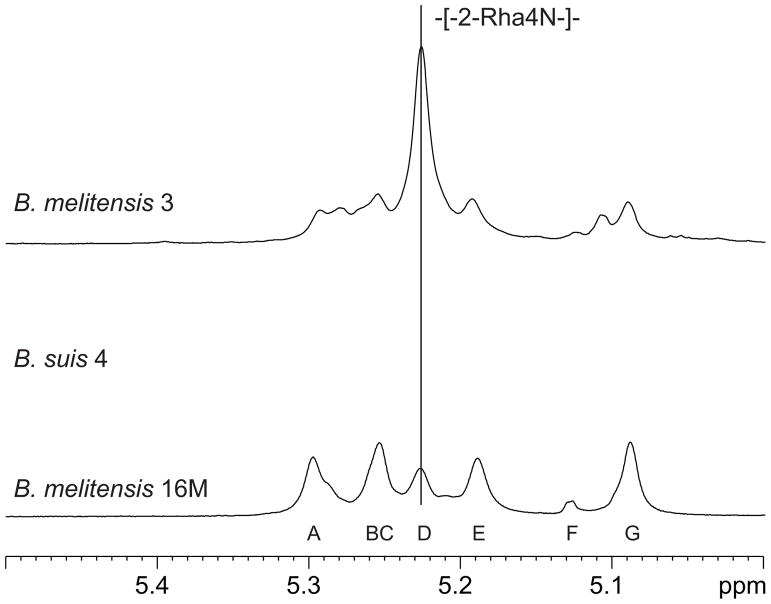

Fig. 1.

Anomeric region of the 1H NMR spectra of B. melitensis strains 3 (upper trace), B. suis 4 (middle) and B. melitensis 16M (lower trace). Sugar labels are as on Fig. 1. The presence of unit D in the B. melitensis 16M polysaccharide was interpreted in earlier publications as an indication of pentasaccharide repeats. In fact, it belongs to a 1–2-linked homopolymer.

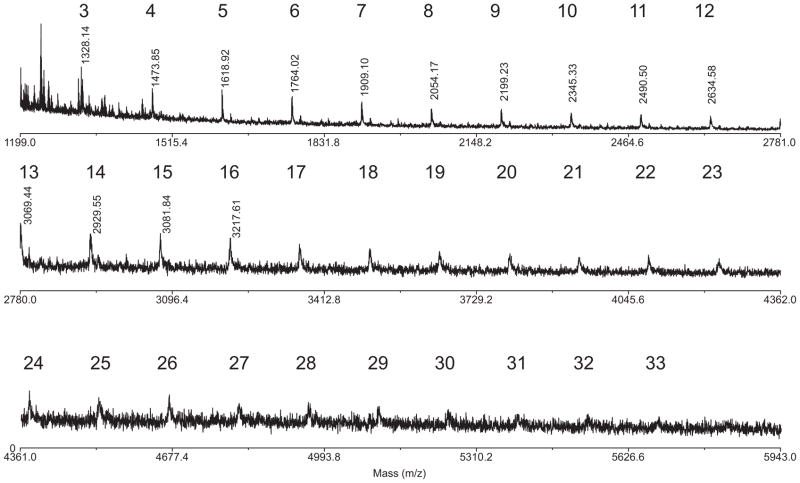

Fig. 4.

MALDI mass spectrum of the N-deformylated polysaccharide from B. melitensis 16M. Numbers above peaks indicate the number of Rha4N residues in the molecular species. Masses are [M+1]+. Mass of the core without Rha4N residues = 893.3 Da. Note the absense of any clustering due to the presence of the tetrasaccharide repeats.

Signals were assigned using gCOSY, TOCSY, NOESY and gHSQC spectra(DQCOSY NMR pulse sequence worked particularly bad on all studied polysaccharides, but gCOSY produced spectra of good quality). Assignments are shown in the Table 1 and illustrated by Fig. 1. The results allowed to conclude that M-epitope is a tetrasaccharide (C-E-G-A), missing one 2-linked Rha4NFo as compared to the previously proposed structure:

Residue F is terminal analog of the residue C inside the polymeric chain, residue B (second from the non-reducing end) is an analog of the in-chain residue E. Separate signals were also visible for terminal unit residues G and A (G′ and A′), but their signals were close to in-chain G and A and for this reason are not listed in the Table 1. Residue D forms an 1–2-linked polymer by itself and showed no NOE connectivities to other spin systems. The following NOE were indicative of the sequence: C1:E2, C1:A5, E1:G2,3, E1:C5, G1:A2,3, A1:C2, A1:G5; B1:G′3, F1:B1,2 (Fig 2). NOE A1:G5, E1:C5, C1:A5 are characteristic for αManp-2-α-Manp (Rha4N has manno-configuration and behaves like mannose) fragments, thus confirming sequence and anomeric configuration of constituent monosaccharides.10

Fig. 2.

Anomeric region of the overlapped COSY (green), TOCSY (red) and NOESY (black) spectra of the B. melitensis 16M polysaccharide. Single number labels are correlations between indicated proton and H-1 of the same residue. Note that unit D shows no NOE to other spin systems, because it belongs to a 1–2-linked homopolymer.

Usually one or two sequential M-type fragments were visible at the non-reducing end of polysaccharides from all strains except B. melitensis strain 16M, where it was a dominant structural element. No other 3-substituted Rha4NFo residues were detected in any Brucella LPS studied here. Whereas position of the terminal M-type tetrasaccharide can be clearly identified, its in-chain variant would look the same regardless of its position, because tracing of its further linkage from the residue A was not possible. Still, considering a fixed position of one 3-substituted Rha4N (third from the end of chain) we suggest that both M-type units are linked together at the non-reducing end of polysaccharide chain. Comparison of the anomeric region of 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 1) showed that all strains contain essentially the same components in different ratio, and also showed that the fifth monosaccharide of the repeating unit described earlier5–8 belongs to a 1–2-linked homopolymer. It showed no NOE except to itself and its intensity varied smoothly from between strains, its intensity in B. melitensis 16M was lower than of the other components of type M unit.

A minor terminal residue of Rha4N not belonging to the tetrasaccharide unit could be identified, representing non-reducing end of 1–2-linked homopolymer. Thus some chains do not contain M-unit at the end, but their amount is much lower than of the chains ending with M-unit.

Polysaccharides of Brucella were quite short, and signals of chain ends were well visible in all NMR spectra. Polysaccharides eluted as broad peaks from size-exclusion columns (Sephadex G-50, Biogel P6), indicating that molecular mass was below 5000 Da (~25–30 Rha4NFo residues). NMR estimate of the chain length was not precise because of inadequately low intensity of the signals of sugar residues in the middle area of polymeric chain. Methylation of N-acetyl derivatives of the polysaccharides gave better estimate. Relative amount of the alditol produced from terminal Rha4NAc to the of 2-substituted Rha4NAc measured by GC with flame-ionization detector showed that B. suis polysaccharide contains on average 8 monosaccharides.

Analysis of the polysaccharides by MALDI mass spectrometry gave supporting and additional information about molecular mass distribution. All polysaccharides produced good quality MALDI mass spectra, but the study of native polysaccharides was complicated by the absence of some formyl groups. One or two formyl group were absent at the reducing end of the polymer (Fig. 3). They might have been lost during polysaccharide isolation or naturally missing. Better spectra without adducts and irregularities were obtained for N-deformylated samples. Generally all spectra looked similar, with differences corresponding to a number of Rha4N residues. B. abortus and B. suis polysaccharides (Fig. 3) were shorter (up to 16 RhaNFo residues) than that of B. melitensis strains 3 and 16M, which contained up to 34 RhaNFo residues (Fig. 4). Masses agreed with the previously published structure of the reducing-end fragment of the polysaccharide chain:9

Fig. 3.

MALDI mass spectrum of the native polysaccharide of B. suis 4. Numbers above peaks indicate the number of Rha4N residues in the molecular species. Masses are [M+22]+. Tall peaks contain one less formyl group than the number of Rha4N residues, next lower mass peaks to the left of each of them correspond to the lack of additional formyl group (28 amu). Mass of the core without Rha4N residues = 893.3 Da. For example, peak at m/z 1407.6 corresponds to a core with 3 Rha4N residues and 2 formyl groups.

The differences between strains were quantitative and depended on the length of 1–2-linked polymer and the number of repeating tetrasaccharides. In B. melitensis 16M the 1–2-linked chain was short but M-type polymer was long. In other strains one or two M-type tetrasaccharides were present at the non-reducing end of chain. Mass spectra did not show any hints of tetrasaccharide repeats, which is not surprising if we assume that tetrasaccharides are attached on top of the 1–2-linked homopolymer of random length.

Tetrasaccharide repeating units defining M epitope formed an extension of the 1–2-Rha4NFo polymer, i.e polymeric chain is 1–2-linked close to reducing end and at some point M-type tetrasaccharide oligo- or polymer starts. This architecture reminds the structure of Klebsiella O1 and O2 polysaccharides, where two types of polysaccharides are connected to each other, forming two antigenic determinants.11

The presence of one or two copies of M-type tetrasaccharide at the non-reducing end of all polysaccharides should be responsible for the detection of M epitope. Relative quantity of M epitope determined by antibody reactions reflects variations of the chain length between strains and the number of M-tetrasaccharides.

1. Experimental part

1.1. Source of LPS

Samples of LPS of B. abortus biotype 4, B. suis strain 4, and B. melitensis strains 3 and 16M, were obtained from Dr. Perry and were previously used for his study of the Brucella LPS.5–8

1.2. NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian INOVA 500 and 600 MHz (1H) spectrometers with Z-gradient probes at 25 °C with acetone internal reference (2.23 ppm for 1H and 31.45 ppm for 13C) using standard pulse sequences gCOSY, TOCSY (mixing time 120 ms), NOESY (mixing time 300 ms), gHSQC, gHMBC (100 ms long range transfer delay). AQ time was kept at 0.8–1 sec for H-H correlations and 0.25 sec for HSQC, 512 increments was acquired for t1.

Assignment of spectra was performed using Topspin 2 (Bruker Biospin) program for spectra visualization and overlap. Monosaccharides were identified by COSY, TOCSY and NOESY cross peak patterns and 13C NMR chemical shifts. Aminogroup location was concluded from high field signal position of aminated carbons (CH at 45–60 ppm). Connections between monosaccharides were determined from transglycosidic NOE and HMBC correlations.

1.3. Mass spectrometry

GC-MS was carried out on Varian Saturn 2000 electron impact ion-trap instrument. GC was performed on Agilent 6950 instrument with flame-ionization detector, HP-1 column, helium carrier gas, 150–280 °C at 4 °C/min. MALDI mass spectra were obtained with DHB matrix on ABSciex 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument.

1.4. N-Deacylation and N-acetylation

PS samples (10 mg each) in polypropylene vials were dissolved in 2 M NaOH (1 mL each), kept 1 h at 100 °C, and neutralyzed with 2 M HCl, desalted by Biogel P6 column (2.5×60 cm) in pyridine-acetate buffer. After lyophilization material contained large amount of acetate (as a counterion to aminogroups). To remove it, a drop of trifluoroacetic acid was added to a polysaccharide solution in 1 mL of water, and sample dried in Spinvac dryer.

N-Acetylation: to a solution of N-deacylated polysaccharide (1–5 mg in 1 mL of water) was added ~100 mg of NaHCO3 and 0.1 mL of Ac2O, mixture stirred 30 min at room temperature, desalted on Sephadex G-15 gel column.

Brucella is an important human and animal pathogen

Polysaccharide antigens of Brucella contain two epitopes called A and M

Corrected structure of the A and M epitopes is proposed based on NMR and MS data

Acknowledgments

Authors are greatly indebted to Dr. M.B.Perry (NRC Canada) for Brucella LPS samples. We thank J. Stupak and K. Chan (NRC Canada) for recording mass spectra. This work was partially supported by the intramural programs of NICHD and NIAID, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Abbreviations

- Rha4NFo

4-formamido-4,6-dideoxy-D-mannose (N-formylperosamine)

- Rha4N

4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-D-mannose (perosamine)

- QuiN

2-amino-2,6-dideoxy-D-glucose (quinovosamine)

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Franco MP, Mulder M, Smits HL. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:775–786. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso PG, Macedo GC, Azevedo V, Oliveira SC. Microb Cell Fact. 2006;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapaque N, Moriyon I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conde-Alvarez R, Arce-Gorvel V, Gil-Ramirez Y, Iriarte M, Grillo MJ, Gorvel JP, Moriyon I. Microb Pathog. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2012.11.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bundle DR, Cherwonogrodzky JW, Perry MB. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8717–8726. doi: 10.1021/bi00400a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundle DR, Cherwonogrodzky JW, Perry MB. FEBS Lett. 1987;216:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80702-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meikle PJ, Perry MB, Cherwonogrodzky JW, Bundle DR. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2820–2828. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2820-2828.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherwonogrodzky JW, Perry MB, Bundle DR. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:979–981. doi: 10.1139/m87-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinogradov E, Kubler-Kielb J. Carbohydr Res. 2013;366:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helander A, Kenne L, Oscarson S, Peters T, Brisson JR. Carbohydr Res. 1992;230:299–318. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)84040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinogradov E, Frirdich E, MacLean LL, Perry MB, Petersen BO, Duus JO, Whitfield C. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25070–25081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]