Abstract

Emerging evidence suggests the existence of a tumorigenic population of cancer cells that demonstrate stem cell-like properties such as self-renewal and multipotency. These cells, termed cancer stem cells (CSC), are able to both initiate and maintain tumor formation and progression. Studies have shown that CSC are resistant to traditional chemotherapy treatments preventing complete eradication of the tumor cell population. Following treatment, CSC are able to re-initiate tumor growth leading to patient relapse. Salivary gland cancers are relatively rare but constitute a highly significant public health issue due to the lack of effective treatments. In particular, patients with mucoepidermoid carcinoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma, the two most common salivary malignancies, have low long-term survival rates due to the lack of response to current therapies. Considering the role of CSC in resistance to therapy in other tumor types, it is possible that this unique sub-population of cells is involved in resistance of salivary gland tumors to treatment. Characterization of CSC can lead to better understanding of the pathobiology of salivary gland malignancies as well as to the development of more effective therapies. Here, we make a brief overview of the state-of-the-science in salivary gland cancer, and discuss possible implications of the cancer stem cell hypothesis to the treatment of salivary gland malignancies.

Keywords: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, Adenoid cystic carcinoma, Perivascular niche, Chemoresistance, Tumor initiating cells

INTRODUCTION

Salivary gland cancer is a relatively rare yet deadly disease. On average, 3,300 new cases are diagnosed every year in the USA. Due to limited mechanistic understanding of the disease and lack of effective regimens for chemotherapy, surgery is still the main treatment option of these patients. As a consequence, treatment for these tumor is generally accompanied by significant morbidity and debilitating facial disfigurement. Malignant tumors are generally fatal. This is reflected in the 5-year survival rate that drops drastically from 78% for stage I tumors to 25%, 21%, and 23% for stages II–IV, respectively.1 Of much concern is the fact that the survival of patients has not improved over the last 3 decades, which is in contrast with the significant improvement in survival observed in other glandular tumors. Such data suggest that focused research efforts on the understanding of the pathobiology of these tumors could lead to significant improvements in patient survival and quality of life.

Mounting evidence supports the existence of a sub-population of tumorigenic cells that possess stem cell-like characteristics in many tumor types (e.g. breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas). These cells, termed cancer stem cells (CSC), are capable of self-renewal and also to differentiate into cells that make up the bulk of the tumor. Cancer stem cells are resilient cells that play a major role in resistance to chemotherapy and radiation therapy in other cancer types.2,3,4 While such studies are unveiling the mechanisms of resistance to therapy in other malignancies, very little is known about the resistance of salivary gland tumors. Indeed, one of the most pressing clinical issues in salivary gland cancer is the poor response to therapy.5 It is certainly possible that low proliferation rates contribute to resistance to therapy in a group of salivary gland tumors but another possibility is that cancer stem cells play a role in the resistance to therapy observed in these tumors. Characterization of stem cells in these tumors might lead to the identification of novel pathways that could be targeted to sensitize these tumors to chemotherapy.

Salivary Gland Structure and Function

Salivary glands play an essential role in protection and maintenance of health in the oral cavity, lubrication of food, taste of food, and speech. Saliva is produced in secretory cells called acini. There are three different types of acini and each is characterized by the composition of the cell secretions. Serous cells release saliva that is abundant in several proteins but lacks mucin protein. Mucous cells secrete saliva-containing mucin proteins attached to carbohydrates.6 Seromucous cells secrete a combination of both mucous and serous saliva. Once the saliva is secreted from these cells, it is transported through intercalated ducts, small excretory ducts, and then through a larger excretory duct that opens into the mouth.6 Excretory ducts are lined with columnar epithelium, cuboidal cells surround the intercalated ducts, and columnar cells make up the striated duct. As the saliva passes through these ducts, additional proteins, such as Immunoglobulin A and lysozyme, from the ductal cells are secreted into the saliva. Myoepithelial cells contract and help secretory cells release the saliva and also promote salivary flow through the ducts.

Salivary glands are subdivided into the major and minor glands. The major salivary glands consist of three pairs of glands that are located around the oral cavity. The largest are the parotid glands that are located in directly below the ears along the jaw. Saliva is exported from the gland directly across from the crowns of the second maxillary molars via the Stensen’s duct, a 5 cm duct connecting the gland to the oral cavity. Secretions from the parotid glands are exclusively serous. The sublingual gland is located underneath the floor of the mouth and are the smallest of the major salivary glands. These glands open to the oral cavity via 8–20 excretory ducts and secrete only mucous saliva.6 The submandibular glands are also located in the floor of the month but are adjacent to the mandibular bone. Saliva is secreted via the Warthon’s duct that opens into the floor of the mouth. This gland secrets seromucous saliva but contains a higher percentage of serous acini then mucous acini. The oral cavity also contains 600–1,000 minor salivary glands that can be found on the tongue, inside of the cheek, lips, floor of the mouth, and the hard palate.6 Secretions from these glands are predominately mucous with the exception of von Ebner’s glands, which are exclusively serous.

Salivary Gland Cancer

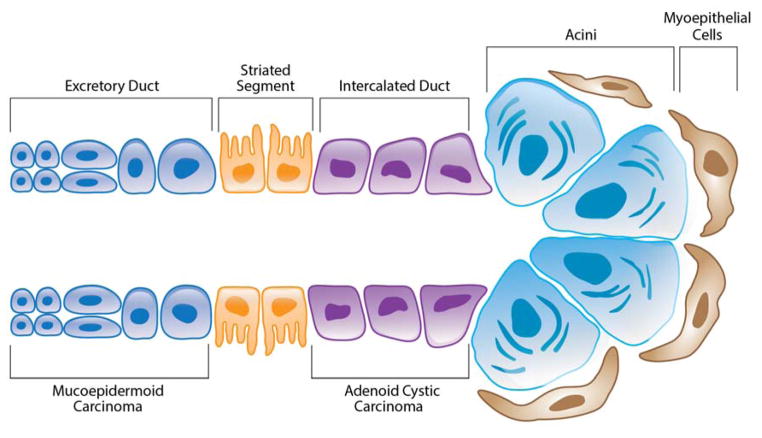

Salivary gland cancers are rare accounting for 2–6.5% of all head and neck cancers with annual incidence of 2.2–3.0 cases per 100,000 people in the United States.7,8,9 Tumors can originate in either the major or minor salivary glands. Approximately 80% of these tumors arise in the parotid gland, 15% arise in the submandibular gland, and 5% arise in the minor and sublingual salivary glands.10 Males have a 51% higher rate of incidence over females, although both tend to develop the cancer within the fifth decade of life.11 While little is known about the pathogenesis of salivary gland cancers, research has shown that radiation exposure is a risk factor and suggests that occupation exposures, viruses, UV light, alcohol, and tobacco may also be involved.12–14 As much as 75% of salivary masses are benign. However, presentation of both malignant and benign tumors is similar making diagnosis and treatment very challenging. Malignant salivary gland tumors are markedly heterogeneous including 24 histologic subtypes, generating significant challenges in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.9 The following discussion is centered on mucoepidermoid carcinomas and adenoid cystic carcinomas (Figure 1), the two most common salivary gland malignancies.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a salivary gland indicating putative areas of origin for mucoepidermoid carcinomas and adenoid cystic carcinomas. Adapted by authors from Bell et al. Salivary gland cancers: biology and molecular targets for therapy. Curr Oncol Rep 2012;14(2):166–174.

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is the most common salivary gland malignancy and represents approximately 5–15% of all salivary gland tumors and 30–35% of all malignant salivary gland tumors.8,15–21 These tumors occur in both the major and minor salivary gland glands and are mostly comprised of epidermoid, mucous, and intermediate cells types. The epidermoid cells are polygonal in shape and characterized by keratinization and intercellular bridges. Mucous cells very in size but all stain positively for mucin proteins. Intermediate cells are thought to functions as progenitor cells for epidermoid and mucous cells and are often basal-like in appearance. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas also contain a variety of other cell types including squamous, clear, columnar, and other uncommon cell types.22–26 They are extralobular tumors and are believed to originate in the excretory duct.22,24

Diagnosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma is based on the presence of both, histological and cytogenetic abnormalities. These tumors are categorized into three grades depending on the amount of cyst formation, the degree of cytological mutation, and the relative number of epidermoid, mucous, and intermediate cell types. Low-grade tumors tend to have a minimal amount of cytological mutation, a high population of mucous cell, and noticeable cyst formation. High-grade tumors contain large areas of intermediate and squamous cells that demonstrate increased mitotic activity. Intermediate-grade tumors manifest a combination of both low and high-grade characteristics. Additional unfavorable histologic factors include perineural invasion, necrosis, increased mitotic rate, angiolymphatic invasion, anaplasia, infiltrative growth pattern, and the presence of a cystic component.27 However, this grading system is often variable making reproducibility difficult.28 Low and intermediate-grade tumors are treated using surgical resections while treatment for high-grade tumors includes neck dissection and radiation therapy.27 While surgical removal and radiation is often successful, a significant number of patients have a recurrence of the disease years later.29 For these patients, few treatments options are available as mucoepidermoid carcinomas are highly chemo-resistant.12 As a result, chemotherapy is used for patient palliation, although ineffective for actual treatment.30 Improved understanding of the pathobiology of the disease leading to rationally designed targeted therapies are necessary to improve the outcome of patients with mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

The most common cytogenetic abnormality in mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a recurrent translocation between chromosomes 11 and 19 creating the CRTC1-MAML2 fusion protein. This translocation is found in 38–81% of mucoepidermoid carcinomas and is expressed in all cell types. CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1) protein activates transcription mediated by cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein.26,31 CREB activated genes regulate cell differentiation and proliferation.32 Abnormal expression of these genes has been shown to lead to cancer development.32 MAML2 is a coactivator for Notch transcriptional activity that regulates cellular differentiation and proliferation.32,33 In the fusion protein, the intracellular Notch-binding domain of MAML2 is replaced by the CREB binding domain of CRTC1.12

Many studies have shown that presence of CRTC-MAML2 translocation has prognostic and diagnostic value.12 Patients with tumors expressing CRTC1-MAML2 have a greater overall survival as well as a lower risk of recurrence and metastasis when compared with fusion-negative tumors.34,35 However, there is a subset of high-grade tumors that express CRTC1-MAML2. Studies by Anzick and colleagues found that in these high-grade tumors expressing CRTC1-MAML2 and additional deletion or hypermethylation of CDKN2A was often found suggesting that the presence or absence of both of these abnormalities may serve as a better diagnostic marker.36 The role this protein plays in the pathogenesis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma is not known, however, research suggests that this mutation occurs early on during tumor initiation.12,27 Studies have shown that this translocation also appears in a subset of Warthin’s tumors and may be linked to the development of these tumors to malignant MEC tumors.34–35,37

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is the second most common malignant salivary gland cancer accounting for 10–25% of patients.37–40 Tumors can occur in both parotid and submandibular glands as well as the minor salivary glands but are believed to arise from the intercalated duct reserve cells found in each of these glands.22,41 Adenoid cystic carcinoma is histologically a biphasic cancer indicating that it is composed of both epithelial and myoepithelial cells.22,42–43 Although growth of these tumors is slow, the long-term prognosis of these patients is poor. The 5-year survival rates are very favorable at 70–90%.39 However, the 15 and 20-year survival rates are rather poor at 35–40% and 10% respectively.39–40,43 Patients with distant metastasis have a 5-year survival rate as low as 20%.38 Overall low survival is primarily due to the persistence of tumor growth, late recurrence after initial treatment, perineural invasion, hematogenous spread and invasion to distant and neighboring tissues.44–47

Diagnosis and determination of tumor grade is based solely on the predominance of one of three histologic growth patterns. The cribriform pattern is easily characterized as having numerous pseudocysts giving a “Swiss cheese” like appearance. These pseudocysts are mostly made of myoepithelial cells. Ductal areas within this pattern are composed of basophilic mucoid material. Tumor cells are cuboidal in shape and are small in size. The tubular pattern has similar shaped tumors cells, however, they constitute small ducts in this case. The inside of these ducts is lined with both basal myoepithelial cells and luminal ductal cells. Tumors containing a solid growth pattern demonstrate large islands of tumors cells with no appearance of cysts of tubules. These areas have higher rates of mitosis, necrosis, and variability in cellular shape. Predominance of tubular and cribriform growth patterns is associated with less aggressive progression and overall longer survival time.27,40,43 Tumors consisting of >30% solid pattern have the highest grading, and are associated with increased aggressiveness and lower survival.43 Though regional metastasis is rare, solid tumors have a greater likelihood of metastasizing to the lymph nodes.43 Biomarkers of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) such as Snail1 and Slug have also emerged as being associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and may be useful in diagnosing adenoid cystic carcinoma.39,40 As all grades are considered aggressive, all ACC patients are treated with surgery and radiation.43 Chemotherapy treatment has low response rate. However, improved understanding of the biology of adenoid cystic carcinomas is leading to clinical trials using target therapies known to work in other cancer types.43

The most common cytological abnormality is a translocation between chromosomes 6 and 9 resulting in the MYB-NFIB fusion protein.48 This translocation occurs in 33–100% of primary ACC samples and expression is not correlated with aggressiveness or grade.31,48–49 Human nuclear factor 1 (NFI) transcription factor contains domains that enable dimerization and DNA-binding. MYB is a transcription factor that regulates genes involved in proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The t(6;9) translocation typically results in loss of exon 15 in the MYB protein, a site shown to bind micro-RNAs, which in turn negatively regulate expression of MYB.48 This leads to overexpression of the fusion protein and overexpression of MYB induced genes, which are involved in cell cycle control, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.48

Recent work has shown that c-Kit and epidermal growth factor (EGF) tyrosine kinase receptors are also over expressed in adenoid cystic carcinoma.50–55 Although it is uncertain the exact mechanism by which overexpression of c-Kit influences cancer growth and progression, it has been suggested that it may influence various genetic and epigenetic processes. EGFR overexpression is commonly found in cancer and promotes cancer development through inhibition of apoptosis and stimulation of angiogenesis.10 Imatinib methylate has been successfully used to inhibit tyrosine kinase receptors in other cancers such as chronic myelogenous leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.56–58 However, little or no response has been observed in adenoid cystic carcinoma.59 Further studies in c-Kit and EGFR may have uncovered the reason for this lack of response. Work by the Bell laboratory demonstrated that expression of c-Kit is found in the inner ductal cells but negative in the myoepithelial cells. Interestingly, the myoepithelial cells showed strong expression of EGFR while the ductal cells showed very little expression. This difference in expression between cell types could lead to complex patterns of drug response. Further research will be necessary to determine the full therapeutic potential of these targets.27

Cancer Stem Cell Hypothesis

The cancer stem cell hypothesis states that tumors are initiated and maintained by a subpopulation of tumorigenic cells capable of continuous self-renewal and differentiation. The idea that stem cells could initiate cancer progression was first suggested over 150 years ago.60–61 However, evidence supporting this hypothesis was not shown until Lapidot and colleagues identified a population of stem-like acute myeloid leukemic cells with enhanced ability to engraft non-obese diabetic severe combined immune-deficient (NOD/SCID) mice.62 Implantation of CD34+CD38− cells effectively recapitulated patient tumors whereas CD34+CD38+ and CD34− cells showed no such ability. Using limiting dilution assays, they showed that approximately 1 in 250,000 cells is a stem cell that can initiate leukemia. This ability was sustained in serial transplantation into secondary mice. The Clarke laboratory further validated this hypothesis in solid tumors. Implantation of CD44+/CD24-Lin-breast cancer cells into NOD/SCID mice also accurately reproduced the original primary tumor heterogeneity using as few as 100 cells.63 Isolation using aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) activity further enriched this cancer stem cell population.64 Cancer stem cells have since been identified in pancreatic, brain, ovarian, colorectal, head and neck, and liver cancers.65–96

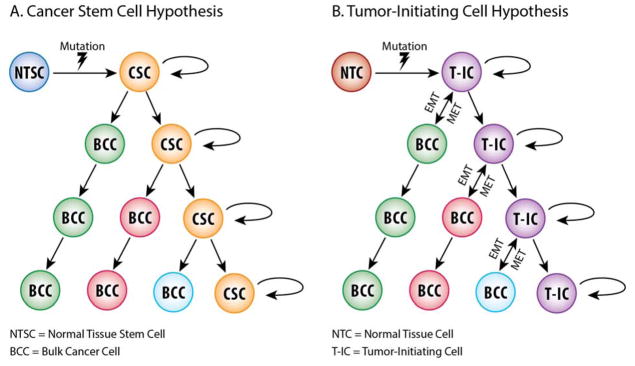

Further characterization of cancer stem cells has identified several properties commonly seen in normal tissue stem cells. Both normal and cancer stem cells are able to undergo self-renewal through asymmetric cell divisions, demonstrate multi-lineage differentiation, show active expression of telomerase as well as increased expression of membrane transporter proteins, and upregulation of anti-apoptotic pathways.97–100 While normal and cancer stem cells share common characteristics, the term cancer stem cell does not necessarily refer to the cell of origin. Currently there are two hypotheses that describe the role of CSC in cancer development (Figure 2). The original hypothesis states that the first oncogenic hit occurs in normal adult stem cells that are then able to differentiate into neoplastic cells. Additional mutations occur as the differentiated stem cells divide to form the bulk tumor. An alternative hypothesis states that normal differentiated cells, called tumor-initiating cells (T-IC), undergo oncogenic mutation and acquire stem cell-like properties enabling them to differentiate and self-renew. These cells are then able to differentiate into the bulk tumor cells. However, work by the Weinberg laboratory suggests that this differentiation is reversible.101 Upon depletion of the tumor-initiating cells population, differentiated cells are able to de-differentiate via epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway.102

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of two prevailing hypotheses for tumorigenesis, i.e. the cancer stem cell hypothesis and the tumor-initiating cell hypothesis. Adapted by authors from Reya et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001;414(6859):105–111.

In addition to tumor initiation, cancer stem cells play an important role in tumor relapse and resistance to chemotherapy. Several studies have shown that this population of cells is resistant to traditional chemotherapeutic and radiation treatments.3–4,103–106 For example, studies have shown that pancreatic cancer stem cells are enriched after treatment with gemcitabine and play a major role in tumor growth and metastasis.65,107 Survival and enrichment of these stem cells allows for re-initiation of tumor growth resulting in patient relapse. Cancer stem cell survival can be attributed to several unique attributes. These cells are typically in G0 making them relatively quiescent and endowing them with resistance to chemotherapeutic agents that act in a cell cycle-dependent manner.108 Studies have also shown that cancer stem cells upregulate DNA damage repair proteins, anti-apoptotic proteins, and transporter proteins such as ABCG2.109–115 For such reasons, the cancer stem cells hypothesis is intriguing in the context of salivary gland tumors, which are not responsive to chemotherapy treatments. Further understanding of pathways involved in cancer stem cell resistance could lead to development of treatments that target this subpopulation of cells thereby sensitizing salivary gland tumors to therapies that eliminate the bulk tumor population.

Emerging research also suggests that the stem cell niche and surrounding microenvironment enables cancer stem cells to survive chemo and radiation treatments as well as to sustain self-renewal and progression of the cancer. The concept of a stem cell niche was first suggested by the Morrison laboratory and is defined as a tissue microenvironment that is capable of taking up and maintaining the function of stem cells.116 A substantial amount of evidence suggests that surrounding cells in the microenvironment are capable of signaling and promoting cancer growth via immune and stromal cell signaling.117 Work by several groups suggests that signaling from the microenvironment specifically acts to maintain and promote survival and self-renewal of the CSC in the stem cell niche. Macrophages play a critical role in the onset of inflammation and the recruitment of other immune cells. These cells have also been shown to activate epithelial cells via NF-kB signaling, increase expression of genes associated with pluripotency thereby maintaining undifferentiated state of the cancer, and increase microvasculature production providing tumors with essential nutrients.118–121 Endothelial cells have also been shown to play a similar role in the tumor microenvironment. Studies in head and neck cancer have shown that cancer stem cell survival and self-renewal is increased when exposed to the growth factor milieu secreted adjacent endothelial cells.93 Fibroblasts have also been shown to be an important component of the microenvironment that helps maintain cancer stem cells. Under normal conditions, fibroblasts function to promote wound healing. In cancer, however, tumor-associated fibroblasts promote both invasion and angiogenesis and secrete factors that promote stemness of cancer stem cells.122 Development of targeted therapies that disrupt the microenvironment in these stem cells niches could inhibit survival and self-renewal properties of cancer stem cells.

Head and Neck Cancer Stem Cells

Increasing evidence indicates that the cancer stem cells play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). While novel treatments have improved the quality of life of patients diagnosed with this cancer, overall survival rates have remained largely unchanged in the last few decades, particularly in patients with advanced disease.123–125 Distant metastasis, loco-regional disease recurrence, and lack of response to chemotherapy are the primary challenges facing these patients.126–130 As cancer stem cells have been implicated in each of these same challenges, further understanding of the biology of these cells in the context of HNSCC could lead to targeted treatments that benefit patients.

Cancer stem cells were first isolated in HNSCC by Prince and colleagues in 2007.88 In these experiments, cells sorted for CD44 expression showed increased tumorigenicity over the cells that lacked CD44 expression. When implanted in NOD/SCID mice, CD44high cells were able to form tumors in 20 out of 31 injections whereas the CD44low population only formed 1 tumor out of 40 total injections. Tumors generated from CD44high cells were phenotypically diverse for CD44 expression indicating that CD44high cells are able to both differentiate in to CD44low cells but also self-renew into CD44high cells. Gene expression analysis of CD44high and CD44-populations showed that CD44high cells highly expressed Bmi-1 while CD44low cells showed no detectable expression of this protein suggesting that CD44 marker enriches for cells with stem cell-like properties. However, mice injected with fewer then 5 × 103 were unable to form tumors indicating that this marker alone may enrich for cancer stem cells but not necessarily be sufficient to isolate a pure population of these cells.

Later experiments by Clay et al suggest that aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), a marker first used in breast cancer, expression may further enrich a cancer stem cell population in HNSCC cells.64,131 ALDH expression was low accounting for about 1.0–7.8% of the total cell population. ALDHhigh populations were highly tumorigenic forming tumors in 7 out of 15 injections with as few as 50–100 cells, and are able to replicate the original tumor heterogeneity. Krishnamurthy and colleagues later showed that the combined expression of ALDH and CD44 further enhanced the ability to identify the cancer stem cell population. Using 1,000 ALDHhighCD44high cells, tumors were formed in 13 out 15 injections while only 3 out of 15 tumors were seen when 10,000 ALDHlowCD44low cells were injected.93

Further characterization of the microenvironment surrounding head and neck cancer stem cells suggests the existence of a perivascular niche that supports stem cell maintenance and resistance to anoikis.93 They observed that approximately 80% of ALDHhigh cells are located within 100-μm radius of neighboring blood vessels. This area was identified as the perivascular niche as it was calculated to be the area of diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from the blood vessels. Exposure to endothelial-cell secreted factors enhanced the expression of ALDH, CD44, and stemness marker Bmi-1, as well as a 3-fold increase in the number of orospheres in low attachment conditions suggesting that endothelial cells play an important role in stem cell self-renewal. Ablation of endothelial cells via an artificial caspase-based death switch drastically decreased the ALDHhighCD44high positive population. Later experiments indicated that endothelial cell regulation of cancer stem cells is in part mediated by IL-6. Although not as potent as full endothelial cell-conditioned media, treatment with rhIL-6 increased in vitro orosphere formation and the tumorigenic potential of cancer stem cells (unpublished observations).

Studies by Campos and colleagues found that upon induction by anchorage and serum starvation, cancer stem cells exposed to endothelial cell-conditioned media were more resistant to anoikis.132 This occurred via the PI-3/Akt pathway that is known to regulate proliferation and cell survival. Endothelial cell-conditioned media induces phosphorylation of Akt. Blocking VEGF decreased Akt phosphorylation. Together, these studies provide evidence of a microenvironment that is capable of supporting and maintaining the cancer stem cell population. Targeting the crosstalk between cancer stem cells and other cells of their supportive niche may provide an effective way to abrogate the tumorigenic function of these cells.

Salivary Gland Cancer Stem Cells

The cancer stem cell hypothesis has yet to be fully explored in salivary gland tumors. However, initial experiments by Sun and colleagues indicate that ALDH isolates cancer stem cells in adenoid cystic carcinomas.133 Using a patient derived xenograft model, serially diluted ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice. Under these conditions, 24 out of 60 injections of 100–1,000 ALDHhigh cells were able to form tumors. Notably, injection of as few as 50 ALDHhigh cells was able to generate a tumor. No tumors were observed in ALDHlow injected mice at similar dilutions of cells. In total, 56/122 injections of ALDHhigh cells formed tumors were only 5/126 injections of ALDHlow cells were able to form tumors. ALDHhigh cells also showed an increased ability to form spheres when plated in low-attachment plates as well as increased invasion in a Matrigel-coated Boyden chamber. ALDHhigh cells infected with luciferase vectors showed increased ability to metastasize when compared to ALDHlow cells. Collectively, these data suggest that ALDH may indeed isolate a more tumorigenic population of cells.

Zhou and colleagues further characterized the expression of ALDH in adenoid cystic carcinomas.134 Immunohistochemical analysis of ALDH expression in human tumors indicated three staining patterns. Approximately 63% of patient’s samples showed staining only in the stromal cells, 26% had neither stromal nor epithelial staining, and 11% had both epithelial and stromal staining. Normal salivary gland showed staining for ALDH only in epithelial cells. However, these different patterns had no correlation to tumor size, perineural invasion, or overall survival. Additional experiments are needed to further verify ALDH as a cancer stem cell marker in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Studies by Fujita and colleagues found overlapping populations of CD44 and CD133 markers in adenoid cystic carcinomas. However, whether or not these markers isolate and more tumorigenic population of cells has yet to be testing in sphere and in vivo models.135

As previously stated, EGFR is commonly upregulated in adenoid cystic carcinoma tumors. Research in other cancer types has demonstrated the role of EGF signaling in the self-renewal of CSC suggesting this pathway may also play a role in the self-renewal of CSC in adenoid cystic carcinoma. A clinical trial in breast cancer determined that treatment with lapatinib, an EGFR/HER2 inhibitor, substantially reduced the CD44high/CD24low stem cell population.136 In the same study, the authors showed that lapatinib decreased mammosphere formation in vitro.136 Korkaya and colleagues further confirmed these results.137 They showed that HER2 signaling significantly increased the Aldefluor stem cell population of normal mammary epithelial cells (NMECs) and increased mammosphere formation. Interestingly, HER2 positive but Aldefluor negative cells were unable to form mammospheres. Notably, this concept was also confirmed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma models.138 HNSCC cells lines transfected with EGFRvIII demonstrated increased proliferation, decreased sensitivity to cisplatin treatment, and increased the CD44high population. The role of EGFR in adenoid cystic carcinoma CSC has yet to be investigated but may be important for understanding the self-renewal and tumorigenicity of these cells.

In addition to EGFR, c-kit (CD117) is also commonly upregulated in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Interestingly, c-kit tyrosine receptor kinase binds stem cell factor (SCF) to trigger pathways involved in the maintenance of progenitor cells.139 Interestingly, this cell surface receptor is commonly used to isolate progenitor cells in submandibular glands.140 Expression of c-kit in these sample overlaps with expression of other commonly knows stem cell markers, (e.g. Nanog, Oct3/4), suggesting it plays an important role in the maintenance of stem cell properties.143 As a marker of stem cells in normal salivary gland, c-kit could also be a potential marker for CSC in adenoid cystic carcinoma as well. Studying the role of this protein in the context of CSC could provide useful insight into the isolation and regulation of these cells.

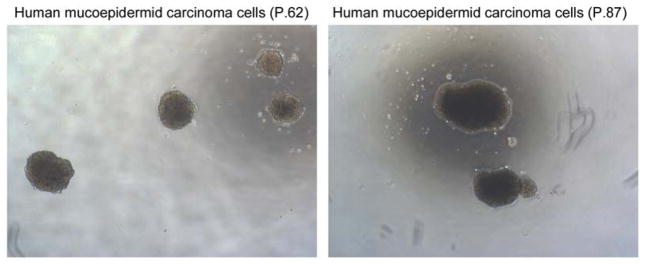

Unpublished work for our group also suggests the presence of CSC in mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Using the mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells lines that our laboratory has generated, we are able to generate orospheres (Figure 3). These structures, first characterized in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma CSC, exploit the fact that stem cells possess anchorage independent growth.141–143 By culturing these cells in low attachment and serum free conditions, we are able to generate orospheres in unsorted cells suggesting that these cell lines do indeed contain a unique stem cell population. Cells cultured in full 10% FBS were unable to form spheres and demonstrated lower viability in low attachment compared to cells cultured in serum free suggesting that our conditions do indeed isolate a stem cell-like population.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of spheres formed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells at passage 62 or 87 cultured in ultra-low attachment plates indicating the existence of cells exhibiting stem-like behavior in this cell line.

Conclusions

The most pressing clinical challenges in treatment of salivary gland cancers are tumor resistance to chemotherapy and the lack of targeted treatments that are safe and effective in these tumors. While surgery and radiation treatment successfully cure a subset of these patients, many present recurrent and/or metastatic disease several years later leading to significant morbidity. Cancer stem cells have been shown to be resistant to chemotherapy and radiation treatments leading to tumor relapse. These cells are also implicated in the progression and development of metastasis. It is possible that cancer stem cells are involved in the processes that result in the late recurrence or metastases that are frequently observed in patients with salivary malignancies. Therefore, selective targeting of this rare sub-population of tumorigenic cancer stem cells could inhibit tumor recurrence and metastasis, and improve patient survival and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenneth Rieger for his help with the illustrations included here. Support for this work was provided by Weathermax foundation, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center; grant from the Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation (AACRF); grant P50-CA-97248 (University of Michigan Head Neck SPORE) from the NIH/NCI, and R21-DE19279, R01-DE21139, and R01-DE23220 from the NIH/NIDCR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Luukkaa H, Klemi P, Leivo I, Koivunen P, Laranne J, Mäkitie A, et al. Salivary gland cancer in Finland 1991–96: an evaluation of 237 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(2):207–214. doi: 10.1080/00016480510003174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ailles LE, Weissman IL. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18(5):460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diehn M, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Therapeutic implications of the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19(2):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7239):780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurie SA, Licitra L. Systemic therapy in the palliative management of advanced salivary gland cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(17):2673–2678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miletich I. Introduction to salivary glands: structure, function and embryonic development. Front Oral Biol. 2010;14:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000313703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speight PM, Barrett AW. Salivary gland tumors. Oral Diseases. 2002;8(5):229–240. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8(3):177–184. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillespie MB, Albergotti WG, Eisele DW. Recurrent salivary gland cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13(1):58–70. doi: 10.1007/s11864-011-0174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell D, Hanna EY. Salivary gland cancers: biology and molecular targets for therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(2):166–174. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boukheris H, Curtis RE, Land CE, Dores GM. Incidence of carcinoma of the major salivary glands according to the WHO classification, 1992 to 2006: a population-based study in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):2899–2906. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neill ID. t(11;19) translocation and CRTC1-MAML2 fusion oncogene in mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Land CE, Saku T, Hayashi Y, Takahara O, Matsuura H, Tokuoka S, et al. Incidence of salivary gland tumors among atomic bomb survivors, 1950–1987. Evaluation of radiation-related risk. Radiat Res. 1996;146(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayne ST, Morse DE, Winn DM. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 674–696. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eversole LR, Sabes WR, Rovin S. Aggressive growth and neoplastic potential of odontogenic cysts: with special reference to central epidermoid and mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Cancer. 1975;35(1):270–282. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197501)35:1<270::aid-cncr2820350134>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezsias A, Sugar AW, Milling MA, Ashley KF. Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma in a child. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(5):512–515. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Fascicle 17. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1996. Tumors of the salivary glands—Atlas of tumor pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gingell JC, Beckerman T, Levy BA, Snider LA. Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Review of the literature and report of a case associated with an apical periodontal cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57(4):436–440. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito FA, Ito K, Vargas PA, de Almeida OP, Lopes MA. Salivary gland tumors in a brazilian population: a retrospective study of 496 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(5):533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luna MA. Salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma: revisited. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13(6):293–307. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000213058.74509.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pires FR, de Almeida OP, de Araujo VC, Kolawski LP. Prognostic factors in head and neck mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):174–180. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akrish S, Peled M, Ben-Izhak O, Nagler RM. Malignant salivary gland tumors and cyclo-oxygenase-2: a histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis with implications on histogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(12):1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alos L, Lugan B, Castillo M, Nadal A, Carreras M, Caballero M, et al. Expression of membrane-bound mucins (MUC1 and MUC4) and secreted mucins (MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, MUC6 and MUC7) in mucoepidermoid carcinomas of salivary glands. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):806–813. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155856.84553.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azevedo RS, de Almeida OP, Kowalski LP, Pires FR. Comparative cytokeratin expression in the different cell types of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(4):257–264. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coxon A, Rozenblum E, Park YS, Joshi N, Tsurutani J, Dennis PA, et al. Mect1-Maml2 fusion oncogene linked to the aberrant activation of cyclic AMP/CREB regulated genes. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7137–7144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaskoll T, Htet K, Abichaker G, Kaye FJ, Melnick M. CRTC1 expression during normal and abnormal salivary gland development supports a precursor cell origin for mucoepidermoid cancer. Gene Expr Patterns. 2011;11(1–2):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell D, Holsinger CF, El-Naggar AK. CRTC1/MAML2 fusion transcript in central mucoepidermoid carcinoma of mandible--diagnostic and histogenetic implications. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14(6):396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Browand BC, Waldron CA. Central mucoepidermoid tumors of the jaws. Report of nine cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40:631–643. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen AM, Granchi PJ, Garcia J, Bucci MK, Fu KK, Eisele DW. Local-regional recurrence after surgery without postoperative irradiation for carcinomas of the major salivary glands: implications for adjuvant therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(4):982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai BL, Xu XF, Fu SM, Shen LL, Zhang J, Guan SM, et al. Nuclear translocation of MRP1 contributes to multidrug resistance of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(12):1134–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhaijee F, Pepper DJ, Pitman KT, Bell D. New developments in the molecular pathogenesis of head and neck tumors: a review of tumor-specific fusion oncogenes in mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and NUT midline carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L, Liu J, Gao P, Nakamura M, Cao Y, Shen H, et al. Transforming activity of MECT1-MAML2 fusion oncoprotein is mediated by constitutive CREB activation. EMBO J. 2005;24(13):2391–2402. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tonon G, Modi S, Wu L, Kubo A, Coxon AB, Komiya T, et al. t(11;19)(q21;p13) translocation in mucoepidermoid carcinoma creates a novel fusion product that disrupts a Notch signaling pathway. Nat Genet. 2003;33(2):208–430. doi: 10.1038/ng1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behboudi A, Enlund F, Winnes M, Andren Y, Nordkvist A, Leivo I, et al. Molecular classification of mucoepidermoid carcinomas-prognostic significance of the MECT1-MAML2 fusion oncogene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45(5):470–481. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okabe M, Miyabe S, Nagatsuka H, Terada A, Hanai N, Yokoi M, et al. MECT1-MAML2 fusion transcript defines a favorable subset of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):3902–3907. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anzick SL, Chen WD, Park Y, Meltzer P, Bell D, El-Naggar AK, et al. Unfavorable prognosis of CRTC1-MAML2 positive mucoepidermoid tumors with CDKN2A deletions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49(1):59–69. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell D, Luna MA, Weber RS, Kaye FJ, El-Naggar AK. CRTC1/MAML2 fusion transcript in Warthin’s tumor and mucoepidermoid carcinoma: evidence for a common genetic association. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(4):309–314. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai Y, Wang R, Zhao YF, Jia J, Sun ZJ, Chen XM. Expression of Neuropilin-2 in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma: its implication in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206(12):793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang J, Tang Y, Zhu G, Zheng M, Yang J, Liang X. Correlation between transcription factor Snail1 expression and prognosis in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(6):764–769. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang Y, Liang X, Zhu G, Zheng M, Yang J, Chen Y. Expression and importance of zinc-finger transcription factor Slug in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(10):775–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Peng B, Chen X. Expressions of nuclear factor kappaB, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and vascular endothelial growth factor in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands: correlations with the angiogenesis and clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(20):7334–7343. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunt JL. An update on molecular diagnostics of squamous and salivary gland tumors of the head and neck. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(5):602–609. doi: 10.5858/2010-0655-RAIR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seethala RR. An update on grading of salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim KH, Sung MW, Chung PS, Rhee CS, Park CI, Kim WH. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(7):721–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880310027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuba HM, Spector GJ, Thawley SE, Simpson JR, Mauney M, Pikul FJ. Adenoid cystic salivary gland carcinoma. A histopathologic review of treatment failure patterns. Cancer. 1986;57(3):519–524. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<519::aid-cncr2820570319>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rapidis AD, Givalos N, Gakiopoulou H, Faratzis G, Stavrianos SD, Vilos GA, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Clinicopathological analysis of 23 patients and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(3):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xue F, Zhang Y, Liu F, Jing J, Ma M. Expression of IgSF in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma and its relationship with invasion and metastasis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(5):295–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Persson M, Andrèn Y, Mark J, Horlings HM, Persson F, Stenman G. Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and neck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18740–18744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909114106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skálová A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards PC, Bhuiya T, Kelsch RD. C-kit expression in the salivary gland neoplasms adenoid cystic carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, and monomorphic adenoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(5):586–593. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holst VA, Marshall CE, Moskaluk CA, Frierson HF., Jr KIT protein expression and analysis of c-kit gene mutation in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1999;12(10):956–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Jr, Prager D, Belani CP, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290(16):2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mino M, Pilch BZ, Faquin WC. Expression of KIT (CD117) in neoplasms of the head and neck: an ancillary marker for adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(12):1224–1231. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000096046.42833.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Soler R. Phase II clinical trial data with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib (OSI-774) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2004;6 (Suppl 1):S20–3. doi: 10.3816/clc.2004.s.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heinrich MC, Blanke CD, Druker BJ, Corless CL. Inhibition of KIT tyrosine kinase activity: a novel molecular approach to the treatment of KIT-positive malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1692–1703. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hotte SJ, Winquist EW, Lamont E, MacKenzie M, Vokes E, Chen EX, et al. Imatinib mesylate in patients with adenoid cystic cancers of the salivary glands expressing c-kit: a Princess Margaret Hospital phase II consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):585–590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohnheim J. Ueber entzundung und eiterung. Path Anat Physiol Kiln Med. 1867;40:1–79.63. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Durante F. Nesso fisio-pathologico tra la struttura dei nei materni e la genesi di alcuni tumori maligni. Arch Memor Observ Chir Pract. 1874;11:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoanq T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCIDmice. Nature. 1994;367(6464):645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(3):313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsay V, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li C, Wu JJ, Hynes M, Dosch J, Sarkar B, Welling TH, et al. c-Met is a marker of pancreatic cancer stem cells and therapeutic target. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(6):2218–2227e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rasheed ZA, Yang J, Wang Q, Kowalski J, Freed I, Murter C, et al. Prognostic significance of tumorigenic cells with mesenchymal features in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(5):340–351. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beier D, Hau P, Proescholdt M, Lohmeier A, Wischhusen J, Oefner PJ, et al. CD133(1) and CD133(−) glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cells show differential growth characteristics and molecular profiles. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4010–4015. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He J, Liu Y, Zhu T, Zhu J, Dimeco F, Vescovi AL, et al. CD90 is identified as a marker for cancer stem cells in primary high-grade gliomas using tissue microarrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(6):M111.010744. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patrawala L, Calhoun T, Schneider-Broussard R, Zhou J, Claypool K, Tang DG. Side population is enriched in tumorigenic, stem-like cancer cells, whereas ABCG21 and ABCG22 cancer cells are similarly tumorigenic. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6207–6219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shu Q, Wong KK, Su JM, Adesina AM, Yu LT, Tsang YT, et al. Direct orthotopic transplantation of fresh surgical specimen preserves CD1331 tumor cells in clinically relevant mouse models of medulloblastoma and glioma. Stem Cells. 2008;26(6):1414–1424. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Boon VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clark ID, Squir JA, Bayani L, Hide T, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Son MJ, Woolard K, Nam DH, Lee J, Fine HA. SSEA-1 is an enrichment marker for tumor-initiating cells in human glioblastoma. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(5):440–452. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baba T, Convery PA, Matsumura N, Whitaker RS, Kondoh E, Perry T, et al. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD1331 ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28(2):209–218. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bapat SA, Mali AM, Koppikar CB, Kurrey NK. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3025–3029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fong MY, Kakar SS. The role of cancer stem cells and the side population in epithelial ovarian cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25(1):113–120. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferrandina G, Bonanno G, Pierelli L, Perillo A, Procoli A, Mariotti A, et al. Expression of CD133-1 and CD133-2 in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(3):506–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, et al. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(30):11154–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang L, Mezencev R, Bowen NJ, Matyunina LV, McDonald JF. Isolation and characterization of stem-like cells from a human ovarian cancer cell line. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;363(1–2):257–268. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang S, Balch C, Chan MW, Lai HC, Matei D, Schilder JM, et al. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4311–4320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Part IK, Liu R, Wang X, Cho RW, et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(24):10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Appelman H, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(8):3382–3389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445(7123):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445(7123):111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Todaro M, Alea MP, Di Stefano AB, Cammareri P, Vermeulen L, Iovino F, et al. Colon cancer stem cells dictate tumor growth and resist cell death by production of interleukin-4. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, Wolf GT, Kaplan MJ, Delerba P, et al. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):973–978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen YC, Chen YW, Hsu HS, Tseng LM, Huang PI, Lu KH, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a putative marker for cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385(3):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krishnamurthy S, Dong Z, Vodopyanov D, Imai A, Helman JI, Prince ME, et al. Endothelial cell-initiated signaling promotes the survival and self-renewal of cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(23):9969–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cheung PF, Cheng CK, Wong NC, Ho JC, Yip CW, Lui VC, et al. Granulin-epithelin precursor is an oncofetal protein defining hepatic cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ma S, Chan KW, Lee TK, Tang KH, Wo JY, Zheng BJ, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase discriminates the CD133 liver cancer stem cell populations. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(7):1146–1153. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Lau CK, Yu WC, Ngai P, et al. Significance of CD90+ _cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang ZF, Ngai P, Ho DW, Yu WC, Ng MN, Lau CK, et al. Identification of local and circulating cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Hepatology. 2008;47:919–928. doi: 10.1002/hep.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yin S, Li J, Hu C, Chen X, Yao M, Yan M, et al. CD133 positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells possess high capacity for tumorigenicity. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(7):1444–1450. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cheng L, Ramesh AV, Flesken-Nikitin A, Choi J, Nikitin AY. Mouse models for cancer stem cell research. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(1):62–71. doi: 10.1177/0192623309354109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Clonal and population analyses demonstrate that an EGF-responsive mammalian embryonic CNS precursor is a stem cell. Dev Biol. 1996;175(1):1–13. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weiss S, Reynolds BA, Vescovi AL, Morshead C, Craig CG, van der Kooy D. Is there a neural stem cell in the mammalian forebrain? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(9):387–393. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(4):704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chaffer CL, Brueckmann I, Scheel C, Kaestli AJ, Wiggins PA, Rodrigues LO, et al. Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(19):7950–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hambardzumyan D, Squatrito M, Holland EC. Radiation resistance and stem-like cells in brain tumors. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(6):454–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. Regulation of mammary stem/progenitor cells by PTEN/Akt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(6):e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shafee N, Smith CR, Wei S, Kim Y, Mills GB, Hortobagyi, et al. Cancer stem cells contribute to cisplatin resistance in Brca1/p53-mediated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3243–3250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Simeone DM. Pancreatic cancer stem cells: implications for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5646–5648. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Venezia TA, Merchant AA, Ramos CA, Whitehouse NL, Young AS, Shaw CA, et al. Molecular signatures of proliferation and quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(10):e301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cai J, Weiss ML, Rao MS. In search of “stemness. Exp Hematol. 2004;32(7):585–598. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cairns J. The cancer problem. Sci Am. 1975;233(5):64–72. 68–77. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1175-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cairns J. Somatic stem cells and the kinetics of mutagenesis and carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(16):10567–10570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162369899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Park Y, Gerson SL. DNA repair defects in stem cell function and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:495–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Potten CS, Owen G, Booth D. Intestinal stem cells protect their genome by selective segregation of template DNA strands. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(11):2381–2388. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.11.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang S, Yang D, Lippman ME. Targeting Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL with nonpeptidic small-molecule antagonists. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(5 Suppl 16):133–142. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wicha MS, Liu S, Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea--a paradigm shift. Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):1883–1890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132(4):598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Polverini PJ, Cotran PS, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Unanue ER. Activated macrophages induce vascular proliferation. Nature. 1977;269:804–806. doi: 10.1038/269804a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cao JX, Cui YX, Long ZJ, Dai ZM, Lin JY, Liang Y, et al. Pluripotency-associated genes in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE-2 cells are reactivated by a unique epigenetic sub-microenvironment. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kim SJ, Kim JS, Papadopoulos J, Wook Kim S, Maya M, Zhang F, et al. Circulating monocytes expressing CD31: implications for acute and chronic angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(5):1972–1980. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Oguma K, Oshima H, Aoki M, Uchio R, Naka K, Nakamura S, et al. Activated macrophages promote Wnt signalling through tumour necrosis factor-alpha in gastric tumour cells. EMBO J. 2008;27(12):1671–1681. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Galiè M, Konstantinidou G, Peroni D, Scambi I, Marchini C, Lisi V, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells share molecular signature with mesenchymal tumor cells and favor early tumor growth in syngeneic mice. Oncogene. 2008;27(18):2542–2551. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(4):765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Haddad RI, Shin DM. Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1143–1154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Allegra E, Baudi F, La Boria A, Fagiani F, Garozzo A, Costanzo FS. Multiple head and neck tumours and their genetic relationship. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29(5):237–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Franchin G, Minatel E, Gobitti C, Talamini R, Vaccher E, Sartor G, et al. Radiotherapy for patients with early-stage glottic carcinoma: univariate and multivariate analyses in a group of consecutive, unselected patients. Cancer. 2003;98(4):765–772. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jones AS, Morar P, Phillips DE, Field JK, Husband D, Helliwell TR. Second primary tumors in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;75(6):1343–1353. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6<1343::aid-cncr2820750617>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Leemans CR, Tiwari R, Nauta JJ, van der Waal I, Snow GB. Recurrence at the primary site in head and neck cancer and the significance of neck lymph node metastases as a prognostic factor. Cancer. 1994;73(1):187–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940101)73:1<187::aid-cncr2820730132>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sjögren EV, Wiggenraad RG, Le Cessie S, Snijder S, Pomp J, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. Outcome of radiotherapy in T1 glottic carcinoma: a population-based study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266(5):735–744. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Clay MR, Tabor M, Owen JH, Carey TE, Bradford CR, Wolf GT, et al. Single-marker identification of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cancer stem cells with aldehyde dehydrogenase. Head Neck. 2010;32(9):1195–1201. doi: 10.1002/hed.21315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Campos MS, Neiva KG, Meyers KA, Krishnamurthy S, Nör JE. Endothelial derived factors inhibit anoikis of head and neck cancer stem cells. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sun S, Wang Z. ALDH high adenoid cystic carcinoma cells display cancer stem cell properties and are responsible for mediating metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396(4):843–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhou JH, Hanna EY, Roberts D, Weber RS, Bell D. ALDH1 immunohistochemical expression and its significance in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Head Neck. 2013;35(4):575–578. doi: 10.1002/hed.23003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fujita S, Ikeda T. Cancer stem-like cells in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands: relationship with morphogenesis of histological variants. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41(3):207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C, Osborne CK, Wu MF, et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):672–679. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Iovino F, Wicha MS. HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population driving tumorigenesis and invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27(47):6120–6130. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Abhold EL, Kiang A, Rahimy E, Kuo SZ, Wang-Rodriguez J, Lopez JP, et al. EGFR kinase promotes acquisition of stem cell-like properties: a potential therapeutic target in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cheng M, Qin G. Progenitor cell mobilization and recruitment: SDF-1, CXCR4, α4-integrin, and c-kit. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;111:243–264. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398459-3.00011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lombaert IM, Hoffman MP. Epithelial stem/progenitor cells in the embryonic mouse submandibular gland. Front Oral Biol. 2010;14:90–106. doi: 10.1159/000313709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dontu G, Wicha MS. Survival of mammary stem cells in suspension culture: implications for stem cell biology and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10(1):75–86. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-2542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255(5052):1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Krishnamurthy S, Nör JE. Orosphere assay: A method for propagation of head and neck cancer stem cells. Head Neck. 2012 Jul 13; doi: 10.1002/hed.23076. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]