Abstract

Lymphatic filariasis is a debilitating disease caused by clade III parasites like Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti. Current recommended treatment regimen for this disease relies on albendazole, ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine, none of which targets the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in these parasitic nematodes. Our aim therefore has been to develop adult B. malayi for electrophysiological recordings to aid in characterizing the ion channels in this parasite as anthelmintic target sites. In that regard, we recently demonstrated the amenability of adult B. malayi to patch-clamp recordings and presented results on the single-channel properties of nAChR in this nematode. We have built on this by recording whole-cell nAChR currents from adult B. malayi muscle. Acetylcholine, levamisole, pyrantel, bephenium and tribendimidine activated the receptors on B. malayi muscle, producing robust currents ranging from > 200 pA to ~1.5 nA. Levamisole completely inhibited motility of the adult B. malayi within 10 min and after 60 min, motility had recovered back to control values.

Keywords: Brugia malayi, acetylcholine receptor, anthelmintic

The Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are a group of parasitic, bacterial, fungal and viral infections that include lymphatic filariasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections (Hotez et al., 2007). Lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, is a debilitating disease caused by adult Brugia malayi, Brugia timori or Wuchereria bancrofti lodging in the lymphatic system of the hosts. Although the disease is largely asymptomatic, acute and chronic infections results in blockage of the lymphatic vessels and fluid accumulation (WHO, January 2012). About 1.3 billion people are at risk of suffering from lymphatic filariasis. Anthelmintics are the main chemotherapeutic agents used for treating parasitic nematode infections because there are currently no effective vaccines on the market. The treatment regimen recommended by the World Health Organization for lymphatic filariasis is albendazole with either diethylcarbamazine or ivermectin administered as a single dose through mass drug administration (MDA) (Ottesen et al., 2008). These drugs help in eliminating circulating microfilariae but do not kill adult parasites. Although MDA is preferable for prevention and treatment of parasitic nematode infections, there are concerns about the development of resistance. Anthelmintic resistance has been reported to the mainstay anthelmintics, namely the cholinergic agonists/antagonists, benzimidazoles and macrocyclic lactones in several species of veterinary parasite (Wolstenholme et al., 2004). There is therefore an urgent need to improve the use of existing anthelmintics, anthelmintic combinations and to develop new ones.

Recent introduction of novel nicotinic anthelmintics to the market has both increased the significance and emphasized the importance of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as anthelmintic target sites. Tribendimidine has been approved for human use in China (Xiao et al., 2005) and has the potential for single-dose MDA (Zhang et al., 2008). Derquantel, a nAChR antagonist (Robertson et al., 2002) has been formulated with abamectin and marketed as Startect ®, and last but not least, monepantel (Kaminsky et al., 2008). Nicotinic AChRs on nematode muscles are also the target for ‘old’ anthelmintics like levamisole and pyrantel. The recent publication of B. malayi draft genome has permitted identification of nAChR subunit genes. According toWilliamson et al. (2007), there are apparently a reduced number of nAChR subunit genes in the B. malayi genome, with orthologues of the nAChR subunit genes lev-1 and lev-8 absent. Interestingly, lev-8 has not been found in the trichostrongylid parasites Haemonchus contortus, Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Teladorsagia circumcincta and the role of lev-1 in forming a receptor has been questioned as lev-1 seems to lack a signal peptide in these parasites (Neveu et al., 2010). There are molecular similarities between B. malayi and Ascaris suum, both belonging to phylogenetic clade III (Blaxter et al., 1998). Single-channel recordings have resulted in the identification of N-, L- and B-subtypes of the nAChR present on A. suum somatic muscles (Qian et al., 2006).

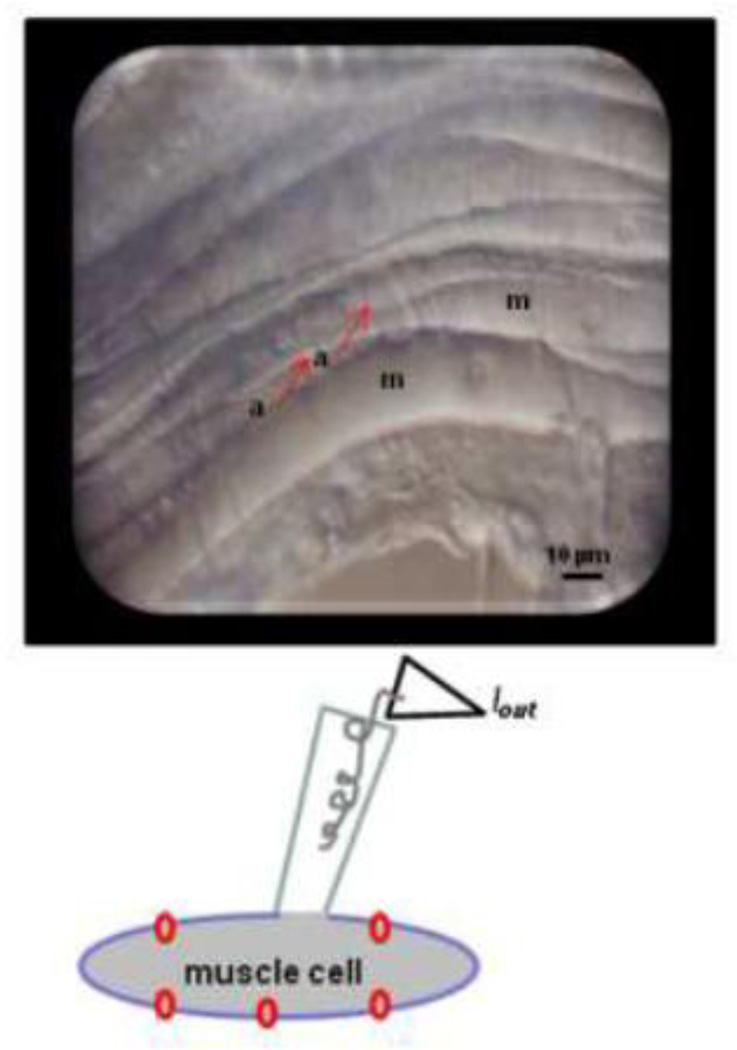

Our aim recently has been to demonstrate that adult B. malayi are amenable to electrophysiological recordings and to engender interest in characterizing the nAChRs in this parasite. In that regard, we have demonstrated that adult B. malayi can be dissected to expose muscle cells for single-channel patch-clamp recordings (Robertson et al., 2011). We recorded single-channel currents from this parasite and observed that the percentage of B. malayi membrane patches containing nAChR events were comparable to what was obtained in A. suum but unlike in the latter parasite, a narrow range of single-channel conductance values were observed for B. malayi. In order to obtain a pharmacological profile of the nicotinic agonists/anthelmintics that can open these channels on B. malayi muscles, we have used the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. Live adult female B. malayi were shipped overnight from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIH/NIAID) Filariasis Research Reagent Resource Centre (FR3; College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, USA). Adult females were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin changed daily. The parasites were held in an incubator at a temperature of 37 °C. Adult worms were used for experiments up to 7 days post delivery. The dissection of B. malayi to expose muscle cells for recordings, collagenase treatment and the pipettes used for the whole-cell recordings are unchanged from our previous report (Robertson et al., 2011). As figure 1 shows, the dissection exposed clear, strap-like muscle cells. The bath solution used was, in mM: NaCl 23, NaAc 110, KCl 5, CaCl2 6, MgCl2 4, HEPES 5, D-glucose 11, and sucrose 10, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. The pipettes were filled with a pipette solution of composition KCl 120 mM, KOH 20 mM, MgCl2 4 mM, Tris 5 mM, CaCl2 0.25 mM, NaATP 4 mM, sucrose 36 mM, EGTA 5 mM, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The preparation was continuously perfused with bath solution at 1 ml/min. We applied 30 µM of the drugs for 5 sec by perfusion. Stock concentrations of the drugs were made in bath solution, except bephenium and tribendimidine which were made in DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO in the bephenium and tribendimidine containing perfusate was 0.1%. An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA, USA) was used to amplify the current signals which were filtered at 2 kHz (3-ple Bessel filter) and sampled at 25 kHz. The signals were digitized with a Digidata 1320A (Axon Instruments Inc.) and stored on a computer hard disk.

Figure 1.

Whole-cell patch-clamp of B. malayi muscle cells. Top: Micrograph of dissected adult female showing the muscle cells (m) and arms (a) projecting to the nerve cord. Below: Diagramatic representation of the whole-cell patch-clamp.

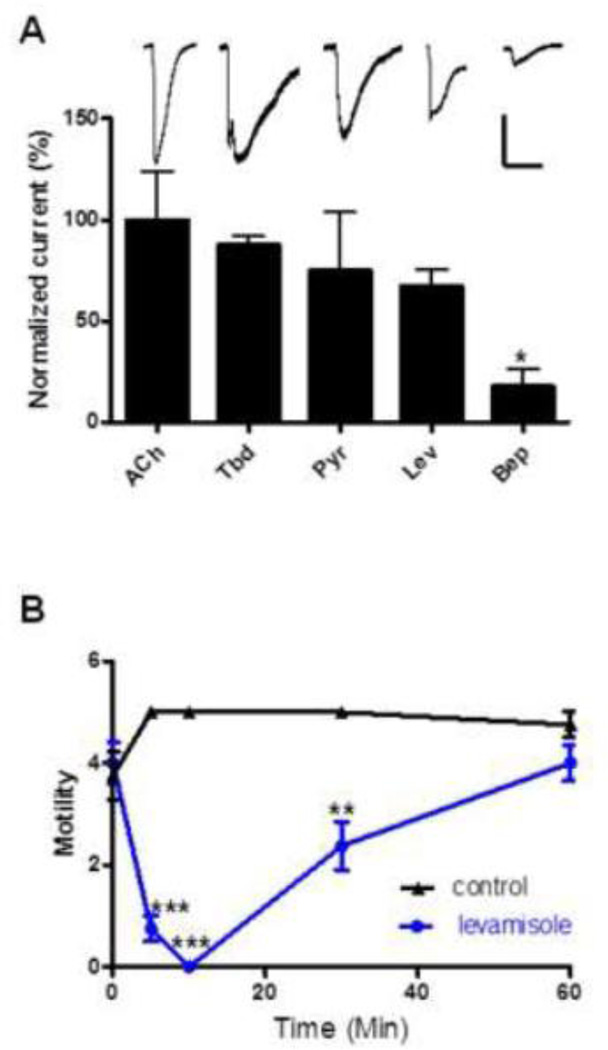

We observed responses to all the drugs we tested, namely acetylcholine and the cholinergic anthelmintics levamisole, pyrantel, bephenium and tribendimidine. Acetylcholine (ACh), supposedly the main excitatory neurotransmitter in this parasite, generated the largest response with average currents of 1504 ± 364 pA (n = 7). Individual ACh responses were normalized to this value as were all other agonist responses to allow for statistical comparison. Tribendimidine was the second most potent agonist and produced average currents of 1316 ± 65 pA, 87.5 ± 4.3 % of ACh currents (Fig. 2A). Pyrantel and levamisole produced average currents of 75.2 ± 28. 6 % (p > 0.05, paired t-test, n = 4, Fig. 2A) and 67.4 ± 8.1 % (p > 0.05, paired t-test, n = 3, Fig. 2A) that of ACh, respectively. Bephenium produced the smallest current response of 266 ± 125 pA, 17.7 ± 8.3 % of ACh currents (p < 0.05, paired t-test, n = 4, Fig. 2A). Next, we investigated the effect of levamisole on the motility of adult B. malayi. Adult worms with ‘normal’ motility were selected for this assay. Normal motility was given a score of 5 and described as worms with active, thrashing-like movement. The worms were placed in separate plates filled with 30 µM levamisole and their motility scored at 5, 10, 30 and 60 min. Because this is a subjective assay, two experienced researchers independently scored the worms. The motility of the adult B. malayi in the presence of levamisole dropped by 85 % in 5 min (p < 0.001, n = 4, student t-test, Fig. 2B) and in 10 min, the worms were completely paralyzed (p < 0.001, n = 4, student t-test, Fig. 2B). The motility of the worms however returned to near control values after 60 min (p > 0.05, n = 4, student t-test) in the drug.

Figure 2.

(A) Bar chart (mean ± s.e) of normalized currents produced by the nAChR agonists/anthelmintics (30 µM) on B. malayi muscles in whole-cell patch-clamp. All current response was normalized to ACh currents (*p < 0.05, paired t-test). Displayed above the bars are sample whole-cell current traces. Scale bar, horizontal 30 secs, vertical 700 pA (B) Plot of motility vs time (min) of adult female B. malayi in the absence and presence of 30 µM levamisole. 4 worms/treatment were used for the assay. Comparisons of motility were made between control and treated worms at each time point, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

In contraction assay and electrophysiological recordings from A. suum muscle, pyrantel > bephenium > levamisole > acetylcholine (Harrow and Gration, 1985; Martin et al., 2004; Trailovic et al., 2008). In reconstituted Haemonchus contortus L-AChRs, levamisole > acetelcholine > pyrantel in Hco-L-AChR1 subtype and in the Hco-L-AChR2 subtype, pyrantel > acetylcholine > levamisole (Boulin et al., 2011). In the B. malayi L-AChR, acetylcholine > tribendimidine > pyrantel ≈ levamisole > bephenium. Our results show that the body muscle nAChR receptor of B. malayi differs from those of other parasites but resembles that of C. elegans (Boulin et al., 2008). This needs further investigation. Although levamisole has been shown to be effective in killing B. malayi, it’s less effective on adult filariae and also less effective than DEC (Mak et al., 1974; Mak and Zaman, 1980). Desensitization of the B. malayi body muscle nAChR may be a reason for the reduced effects of levamisole on the adult worms. Last but not least, we suggest that there are likely to be other subtypes of the nAChR in B. malayi. We have demonstrated through whole-cell patch-clamp recordings that nAChRs on adult B. malayi muscle cells are activated by the cholinergic anthelmintics levamisole, pyrantel, bephenium and tribendimidine. Levamisole reversibly paralyzed the adult worms.

Highlights.

We report whole-cell patch-clamp recording of adult Brugia malayi muscle nAChR.

Agonist potency was acetylcholine>tribendimidine>pyrantel≈levamisole>bephenium.

Levamisole reversibly inhibited motility of adult B. malayi.

Adult B. malayi muscle nAChR differ in pharmacology from Ascaris suum.

Reduced effect of levamisole on adult B. malayi may be due to desensitization.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of NIH NIAID R56 AI047194 – 11 to R.J.M, NIH Funding for this study was provided by Iowa Center for Advanced Neurotoxicology (ICAN) grant to APR and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH) grant R 01 A1047194 to RJM and NIAID1R21AI092185-01A1 to APR. The authors would like to thank the Filariasis Research Reagent Resource Centre (FR3), College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, USA for the supply of live adult worms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blaxter M, De Ley P, Garey J, Liu L, Scheldeman P, Vierstraete A, Vanfleteren J, Mackey L, Dorris M, Frisse L, Vida J, Thomas W. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998;392(6671):71–75. doi: 10.1038/32160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Gielen M, Richmond JE, Williams DC, Paoletti P, Bessereau J-L. Eight genes are required for functional reconstitution of the Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor. PNAS. 2008;105:18590–18595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806933105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Fauvin A, Charvet CL, Cortet J, Cabaret J, Bessereau J-L, Neveu C. Functional reconstitution of Haemonchus contortus acetylcholine receptors in Xenopus oocytes provides mechanistic insights into levamisole resistance. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1421–1432. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow I, Gration K. Mode of action of the anthelmintics morantel, pyrantel and levamisole on muscle cell membrane of the nematode Ascaris suum. Pesticide Science. 1985;16(6):662–672. [Google Scholar]

- Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli L. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1018–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky R, Gauvry N, Schorderet Weber S, Skripsky T, Bouvier J, Wenger A, Schroeder F, Desaules Y, Hotz R, Goebel T, Hosking B, Pautrat F, Wieland-Berghausen S, Ducray P. Identification of the amino-acetonitrile derivative monepantel (AAD 1566) as a new anthelmintic drug development candidate. Parasitol Res. 2008;103(4):931–939. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak J, Zaman V, Sivanandam S. Antifilarial activity of levamisole hydrochloride against subperiodic Brugia malayi infection of domestic cats. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23(3):369–374. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1974.23.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak J, Zaman V. Drug trials with levamisole hydrochloride and diethylcarbamazine citrate in Bancroftian and Malayan filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1980;74(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(80)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RJ, Clark CL, Trailovic SM, Robertson AP. Oxantel is an N-type (methyridine and nicotine) agonist not an L-type (levamisole and pyrantel) agonist: classification of cholinergic anthelmintics in Ascaris. International Journal for Parasitology. 2004;34:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveu C, Charvet CL, Fauvin A, Cortet J, Beech RN, Cabaret J. Genetic diversity of levamisole receptor subunits in parasitic nematode species and abbreviated transcripts associated with resistance. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2010;20:414–425. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328338ac8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottesen EA, Hooper PJ, Bradley M, Biswas G. The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: Health Impact after 8 years. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(10):e317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Martin RJ, Robertson AP. Pharmacology of N-, L- and B-subtypes of nematode nAChR resolved at the single-channel level in Ascaris suum. FASEB J. 2006;20:2606–2608. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6264fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AP, Clark CL, Burns TA, Thompson DP, Geary TG, Trailovic SM, Martin RJ. Paraherquamide and 2-Deoxy-paraherquamide Distinguish Cholinergic Receptor Subtypes in Ascaris suum. The Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;302:853–860. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.034272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AP, Puttachary S, Martin RJ. Single-channel recording from adult Brugia malayi. Invert Neurosci. 2011;11:53–57. doi: 10.1007/s10158-011-0118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trailovic SM, Verma S, Clark CL, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. Effects of the muscarinic agonist: 5-methylfurmethiodide, on contraction and electrophysiology of Ascaris suum muscle. International Journal for Parasitology. 2008;38(8–9):945–957. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Lymphatic Filariasis. Fact Sheet N°. 2012 Jan;102 [Google Scholar]

- Williamson S, Walsh T, Wolstenholme AJ. The cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel gene family of Brugia malayi and Trichinella spiralis: a comparison with Caenorhabditis elegans. Invert Neurosci. 2007;7:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s10158-007-0056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme AJ, Fairweather I, Prichard R, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Sangster NC. Drug resistance in veterinary helminths. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Hui-Ming W, Tanner M, Utzinger J, Chong W. Tribendimidine: a promising, safe and broad-spectrum anthelmintic agent from China. Acta Trop. 2005;94(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xiao S, Wu Z, Qiu D, Wang S, Wang S, Wang CC. Tribendimidine enteric coated tablet in treatment of 1,292 cases with intestinal nematode infection-a phase IV clinical trial. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2008;26:6–9. in Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]