Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the outcome, and optimal duration of medical treatment in children with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS). Eighteen children with SMAS were retrospectively studied. The data reviewed included demographics, presenting symptoms, co-morbid conditions, clinical courses, nutritional status, treatments, and outcomes. The three most common symptoms were postprandial discomfort (67.7%), abdominal pain (61.1%), and early satiety (50%). The median duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 68 days. The most common co-morbid condition was weight loss (50%), followed by growth spurt (22.2%) and bile reflux gastropathy (16.7%). Body mass index (BMI) was normal in 72.2% of the patients. Medical management was successful in 13 patients (72.2%). The median duration of treatment was 45 days. Nine patients (50%) had good outcomes without recurrence, 5 patients (27.8%) had moderate outcomes, and 4 patients (22.2%) had poor outcomes. A time limit of >6 weeks for the duration of medical management tended to be associated with worse outcomes (P=0.018). SMAS often developed in patients with normal BMI or no weight loss. Medical treatment has a high success rate, and children with SMAS should be treated medically for at least 6 weeks before surgical treatment is considered.

Keywords: Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome; Medical Treatment, Outcome; Children

INTRODUCTION

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS) is a symptom complex resulting from vascular compression of the third portion of the duodenum between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the aorta (1). SMAS is frequently associated with rapid linear growth without weight gain, scoliosis, spinal surgery, weight loss, and an abnormally high position of the ligament of Treitz (2-5). The typical symptoms of SMAS are similar to those of incomplete duodenal obstruction, including postprandial fullness, intermittent abdominal pain, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

This condition can be diagnosed by the radiologic evidence of vascular obstruction of the third portion of the duodenum using a barium upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series, computed tomography (CT), CT angiography or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). However, the identification of SMAS can be difficult and diagnostic delays are common because of lack of high indices of clinical suspicion (4, 6). A diagnosis of SMAS is usually made by a process of exclusion, and such delays result in ineffective symptomatic therapies and inappropriate investigations.

Many of SMA obstruction cases can be resolved with nutritional treatment, but surgical intervention is required in some patients. There is no data on the appropriate duration of medical treatment before consideration of surgical correction and on the association with worse outcomes of SAMS in children. The aims of this study were to evaluate the clinical features and outcomes of SMAS and to determine the optimal duration of medical treatment in children with SMAS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We collected 23 patients who were diagnosed with SMAS between February 2003 and January 2013. All diagnoses of SMAS were established based on the findings of a barium UGI series: dilatation of the first and second portions of the duodenum, abrupt compression of the third portion of the duodenum, and antiperistaltic waves of barium proximal to the obstruction. Five patients were excluded because of insufficient medical records. Thus, we analyzed a total of 18 patients with SMAS.

The following parameters were recorded and analyzed: demographics, presenting symptoms, co-morbid conditions, clinical courses, nutritional statuses, treatments, and outcomes. The weight-for-age, body mass index (BMI)-for-age, and weight-for-height Z scores were used to evaluate each patient's nutritional status before and after treatment. The Z scores were computed according to the stature percentiles of the Korean National Growth Charts drafted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The BMI-for-age Z score was classified as severely wasted (Z score <-3), wasted (-3≤Z score <-2), normal (-2≤Z score <1), possible risk of overweight (1≤Z score <2), overweight (2≤Z score<3), or obese (Z score≥3) according to the WHO Child Growth Standards (7).

The results of medical treatment were divided to 3 categories: response, partial response, and non-response. A response was defined as improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms with medical treatment, a partial response as slight improvement, and a non-response as no improvement. A recurrence was defined as the reappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms after response to medical treatment.

On the basis of responses to the medical treatment and recurrences, the outcomes of the patients who received medical treatment were classified into 3 groups: good, moderate, and poor. A good outcome was defined as a response without recurrence after medical treatment. A moderate outcome was defined as a partial response or response to retreatment after recurrence. A poor outcome was defined as a non-response to medical treatment or to retreatment after recurrence.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Growth statuses before and after medical treatment were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the Mann-Whitney U test. The associations between the durations of medical treatment and the outcomes were analyzed using the Chi-square-test of linear by linear test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chungnam National University Hospital (IRB No. 2013-03-022-001). Informed consent was exempted by the board.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

The total number of patients available for this study was 18; 11 (61.1%) were female. The patients' ages ranged from 8.5 to 16.2 yr (median, 11.9 yr) at diagnosis. The body weight ranged from 22 to 61 kg (median, 36.5 kg). The height ranged from 129 to 178 cm (median, 160.5 cm). The mean weight-for-age Z score and height-for-age Z score were -0.75 and 0.81, respectively. The BMI ranged from 12.2 to 19.7 kg/m2 (mean, 15.6 kg/m2). The mean BMI-for-age and weight-for-height Z scores were -1.55 and -1.86, respectively. Nine patients (50%) who had shown weight loss before diagnosis of SMAS lost weight by 2 to 17 kg (mean 6.7 kg). Of these 9 patients, 7 (77.8%) lost more than 10% of their body weight. Four patients (22.2%) were wasted, 1 (5.6%) was severely wasted, and 13 (72.2%) were normal in BMI-for-age Z scores.

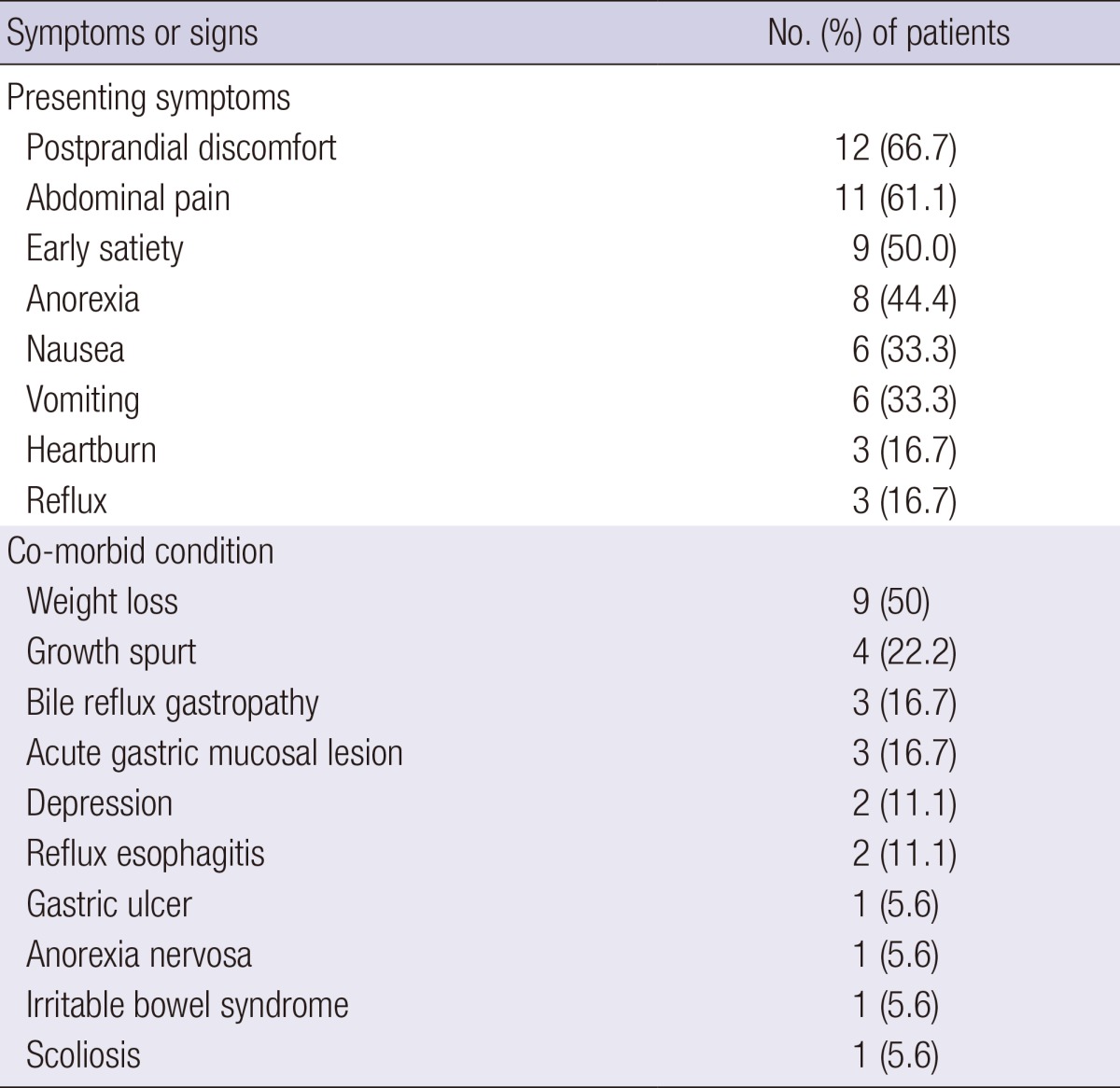

The presenting symptoms and co-morbid conditions are shown in Table 1. Duration of symptoms before the diagnosis ranged from 1 to 730 days (median, 68 days). The 3 most common symptoms were postprandial discomfort (67.7%), abdominal pain (61.1%), and early satiety (50%). Other symptoms included anorexia (44.4%), nausea (33.3%), vomiting (33.3%), heartburn (16.7%), and reflux (16.7%). All patients had a constellation of the above mentioned symptoms: 2 (33.3%), 3 (33.3%), 4 (11.1%), and 5 (22.2%).

Table 1.

Presenting symptoms and co-morbid conditions of patients with SMAS

SMAS, superior mesenteric artery syndrome.

Sixteen (88.9%) of the patients with SMAS had co-morbid conditions (Table 1). The most common co-morbid condition was weight loss (50%), followed by growth spurt (22.2%), bile reflux gastropathy (16.7%), and acute gastric mucosal lesion (16.7%). Other less-infrequent conditions included depression, reflux esophagitis, gastric ulcer, anorexia nervosa, irritable bowel syndrome, and scoliosis.

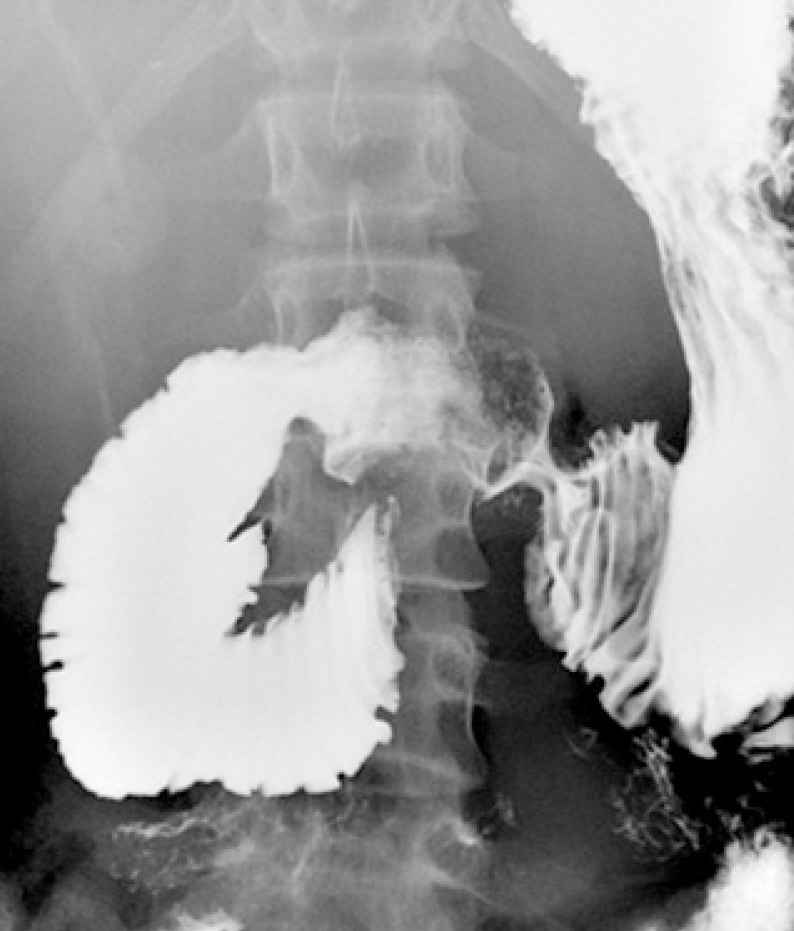

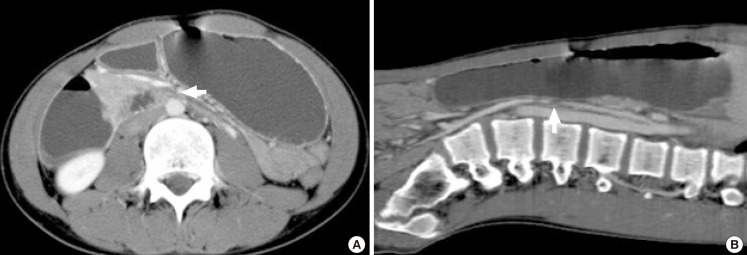

All patients underwent barium UGI series and upper endoscopy. On UGI series, all patients had an abrupt vertical cut off of the third portion of the duodenum with dilatations of the first and second portions and also antiperistaltic movement of the barium proximal to the obstruction (Fig. 1). Endoscopy revealed bile reflux gastropathy, acute gastric mucosal lesions, reflux esophagitis, or gastric ulcers in 8 patients (Table 2). Abdominal CT was performed on 8 patients (44.4%) and a gastric emptying time (GET) scan was performed on 6 patients (33.3%) at diagnosis. On abdominal CT, mean SMA angles and SMA-aorta distances were 12.8° (range, 9°-18.8°) and 3.9 mm (range, 2.3-5.3 mm), respectively (Fig. 2). GET ranged from 99 to 385 min (mean, 253 min).

Fig. 1.

Upper gastrointestinal series shows an abrupt cutoff of the third portion of the duodenum and dilatations of the first and second portions of the duodenum.

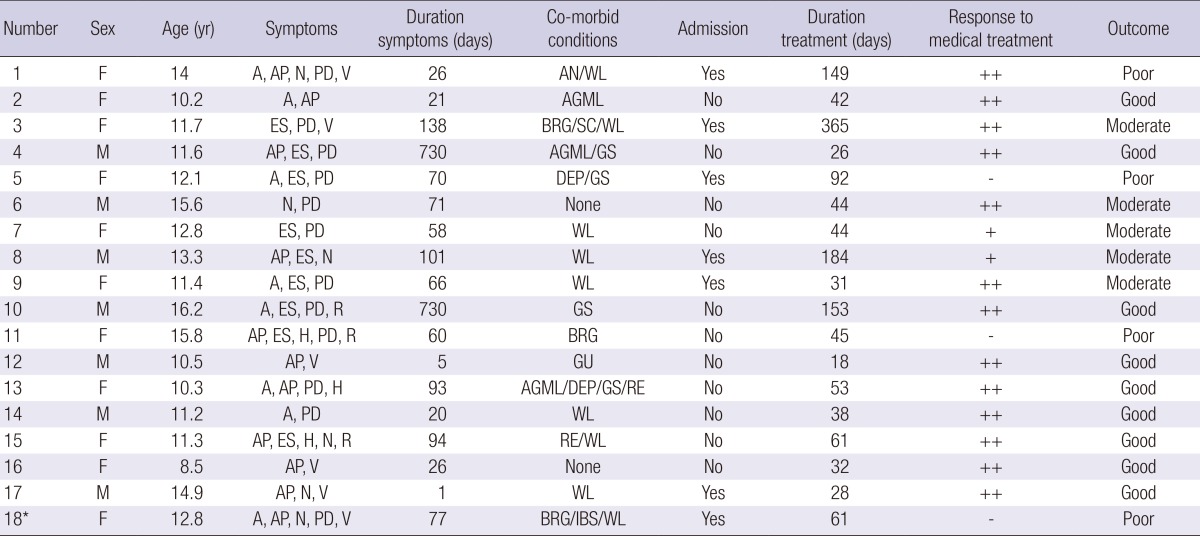

Table 2.

Clinical features and outcomes of patients with SMAS

*Patient underwent surgical treatment.

A, anorexia; AP, abdominal pain; ES, early satiety; H, heartburn; N, nausea; PD, postprandial discomfort; R, reflux; V, vomiting; AGML, acute gastric mucosal lesion; AN, anorexia nervosa; BRG, bile reflux gastropathy; DEP, depression; GS, growth spurt; GU, gastric ulcer; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; RE, reflux esophagitis; SC, scoliosis; WL, weight loss ++, response; +, partial response; -, non-response.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal 3D CT scan shows gastric and proximal duodenal dilatations with compression of the third portion of the duodenum (arrows) between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta. The aortomesenteric distance in this patient was 4 mm (A) and the aortomesenteric angle was 9.5° (B).

Clinical course and outcome

All patients began with conservative treatment. Table 2 summarizes the clinical features and outcomes of the patients with SMAS. Medical treatment was successful in 13 patients (72.2%). Abdominal symptoms were relieved by postprandial changes to the left lateral decubitus or in the prone position in 12 (70.6%) of the 17 patients. Patients took the following medications: prokinetics (domperidone or metoclopramide) in 17 patients (94.4%), histamine H2 receptor antagonists in 13 patients (72.2%). Seven patients (38.9%) were admitted for parenteral nutrition, and 2 patients required nasogastric tube placement for bowel decompression. The median duration of parenteral nutrition was 20 days (range, 7-127 days). Of these 7 inpatients, 4 improved with medical treatment, 1 slightly improved, and 2 did not improve. Of the 11 patients who were treated on an outpatient base, 9 improved, 1 slightly improved, and 1 did not improve.

Of the 13 patients who responded to the medical treatment, there were recurrences in 4 patients (30.8%). Three of these 4 patients had success with further medical treatment and 1 did not improve with medical retreatment because of anorexia nervosa. Of the 5 patients who had failed medical treatment, 1 female presented with persistent anorexia, abdominal pain, and vomiting despite 2 months of medical treatment. These symptoms improved within 2 weeks after laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy. The others were lost to follow-up.

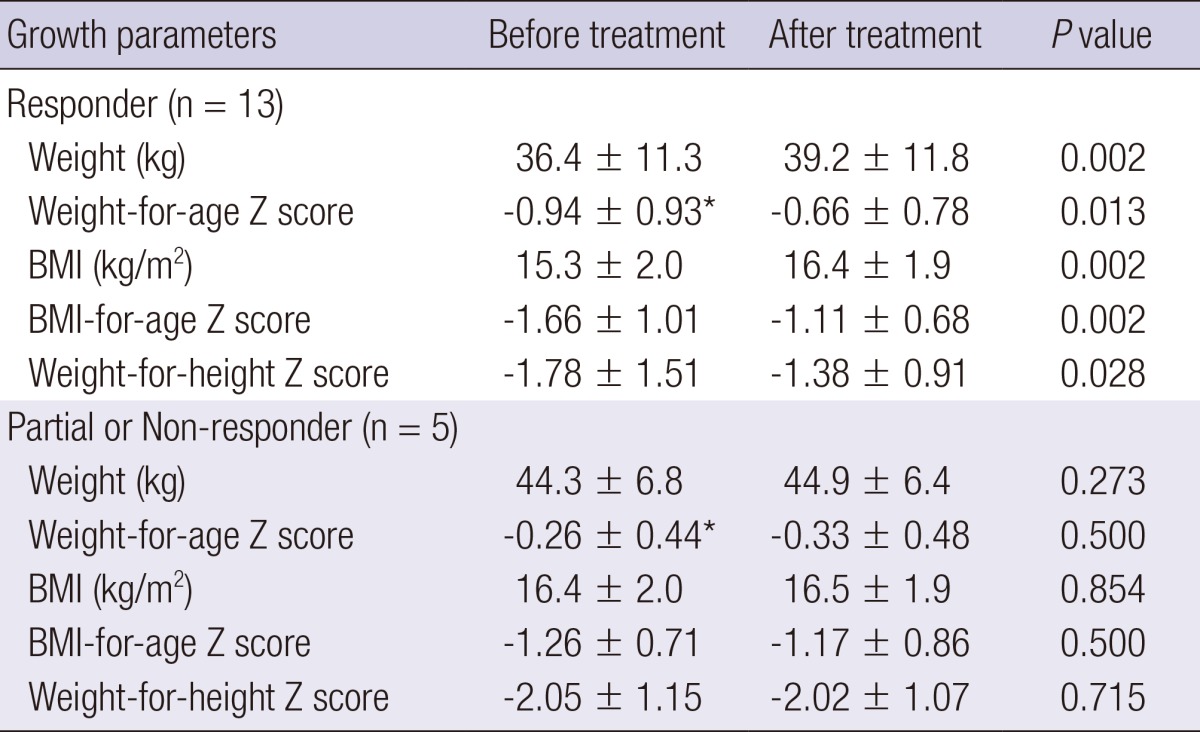

The median duration of treatment was 45 days (range, 18-365 days) and the median follow-up period was 57 days (range, 18-376 days). After medical treatment, 15 patients (83.3%) had weight gain and the mean weight gain was 2.2 kg (range, -0.6-9.2 kg). The mean weight and weight-for-age Z-score were 40.8 kg and -0.57, respectively. The mean BMI and BMI-for-age Z-score were 16.4 kg/m2 and -1.12, respectively. The mean weight-for-height Z-score was -1.56. All indices significantly increased in the group that responded to treatment compared to indices from before treatment (Table 3). Weight-for-age Z scores before treatment were significantly different between the medical responders and the partial/non-responders (P=0.026).

Table 3.

Comparison between growth statuses before and after medical treatment

Values are expressed as mean±SD. *Comparisons between the responders and partial responders/non-responders (P=0.026).

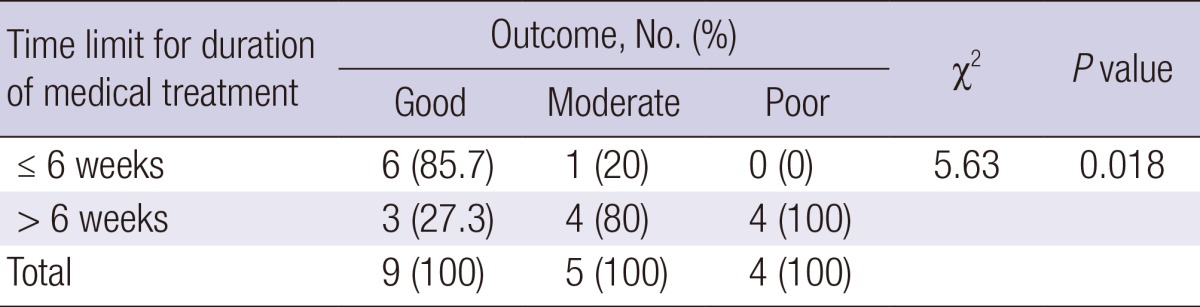

Finally, 9 patients (50%) had good outcomes without recurrences, 5 (27.8%) moderate outcomes, and 4 (22.2%) poor outcomes with medical treatment. In assessment of the association between the durations of medical treatment and outcomes, a time limit of >6 weeks seemed to be associated with worse outcomes (P=0.018) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between durations of medical treatment and outcomes

χ2-test of linear by linear association.

DISCUSSION

The present retrospective analysis of our 10-yr experience contributes to our understanding of the clinical features as well as clinical courses and outcomes of medical management for children with SMAS. We make the first attempt to evaluate the appropriate period for medical treatment before any consideration of surgical treatment. Our results indicate that children with SMAS should have a trial of at least 6 weeks of medical treatment before consideration of surgical intervention.

In our study, SMAS affected females more commonly than males. Postprandial discomfort, abdominal pain, and early satiety were the major presenting symptoms. All patients had 2 or more symptoms. These results support the findings of other studies in children with SMAS (5, 8). The median duration of symptoms before the diagnosis is variable from 5 days to 18 months (5, 9). In our study, the median duration was 68 days (range, 1-730 days) before diagnosis. This indicates that SMAS can present acute or chronic in nature.

Low BMI, weight loss, and growth spurts are well-known risk factors of SMAS (5, 10). Some previous studies suggest that low BMI or weight loss is not a prerequisite for the development of SMAS (5, 10). BMI was normal in 72.2% of our patients and no weight loss was recorded in 50%. Ozbulbul et al. (11) have reported that SMA angle correlates better with visceral fat than with BMI in adults, whereas BMI correlates better with subcutaneous fat than with visceral fat. Unal et al. (12) have shown that the SMA-aorta distance (aortomesenteric distance; AMD) significantly correlates with BMI. The reason for the development of SMAS in children with normal BMI is not yet known. In our study, weight loss developed in 9 patients with bacterial enteritis, post-appendectomy, anorexia nervosa, or food intolerance. Of these 9 patients, 6 (66.7%) responded to medical management, and 50% experienced recurrence. Weight loss is commonly associated with the development of SMAS, resulting in a vicious cycle (5, 14). However, weight loss did not significantly affect clinical outcomes. There were 4 patients who experienced growth spurts without the appropriate weight gain. Of these patients, 3 (75%) responded to medical treatment. Rapid linear growth without weight gain may result in an elongated mesentery as well as loss of the mesenteric root fat pad. This explains why SMAS occurred in our 4 patients during their growth spurt.

The traditional diagnostic method for SMAS is UGI series. The following radiological criteria are reported to be indicative of SMAS: dilatation of the first and second parts of the duodenum, abrupt vertical or oblique compression of the third part of the duodenum, antiperistaltic waves of barium proximal to the obstruction, significant delays in gastroduodenal transit, and relief of obstruction after postural changes (2, 14).

Most cases of SMAS have recently diagnosed by abdominal CT (4, 10). Its diagnostic criteria include a reduction in the SMA angle from the normal values of 28°-65° to <22°, a decrease in the SMA-aorta distance from the normal values of 10-28 mm to <8 mm, and gastric and proximal duodenal dilatation with obstruction of the third part of the duodenum (16-18). In our study, the mean SMA angle and SMA-aorta distance were 12.8° (range, 9°-18.8°) and 3.9 mm (range 2.3-5.3 mm), respectively. A SMA angle of <22°-25° and a SMA-aorta distance of <8 mm correlated well with development of SMAS symptoms in adults (1, 12, 15, 18). Thus, these are commonly used as cutoff values for the diagnosis of SMAS in adults.

However, there are no established cutoff values for diagnosing SMAS in children. Arthurs et al. (19) found that the mean SMA angle was 45.6°±19.6° (range, 10.6°-112.9°) and the mean SMA-aorta distance was 11.3±4.8 mm (range, 3.6-35.3 mm) in normal children. They also described that 9.3% of asymptomatic children were diagnosed with SMAS based on an SMA angle of <25° and that 20% of asymptomatic children were diagnosed with SMAS based on an SMA-aorta distance of <8 mm. These findings suggest that there is a wide range of normal values of SMA angles in asymptomatic children and that absolute cutoff values of SMA angles may not be the best indicator of SMAS. Therefore, CT results should be used with caution as a gold standard in the diagnosis of children with SMAS.

The initial treatment of SMAS should always be conservative: maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balances, stomach decompression, and nutritional support (8). Small frequent high caloric feedings with postprandial assumption of the left lateral decubitus, knee-chest, or prone positions may be helpful (4). If symptoms persist, enteral feeding through a nasojejunal tube passed distal to the compression or parenteral nutrition may be required, aiming at increasing the mesenteric fat pad, which in turn increases the SMA angle (9, 20). Nasojejunal feeding tubes were not used in our patients because they refused it. The patients were supported by parenteral nutrition. Concomitant treatment with antacids, histamine H2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, or anti-depressants may also be useful for treating the symptoms and presenting co-morbidity conditions (4, 10).

Positive response rates to medical management as documented in larger series have been observed in 71.3% (57/80) (10) and 83% (38/46) (21), and in 14% (3/22) (9), 52% (14/27) (4), and 82% (18/22) (5) of pediatric cases. Ha et al. (9) reported that the success rate of children is as low as 14%, which resulted from low compliance with medical treatment and little fear of surgery. In our study, the response rate to medical treatment was 72.2% (13/18) and the recurrence rate was 30.8%. The rate of outpatient care was 61% (11/18), which was higher than those of other studies (4.5% [1/22] and 8.8% [7/80]) (4, 5). Of the outpatients, the response rate to medical treatment was 82% (9/11). Depending on the severity of symptoms, patients can be treated at the outpatient clinic. Recent advances in nutritional treatments have also led to a substantial shift towards medical treatment rather than surgery (10).

Similar to a previous study (4), our study showed that there were no significant differences in sex, age, the duration of symptoms, height, weight, BMI, weight loss, weight for height, SMA angle, and SMA-aorta distance between the responders and the partial/non-responders to medical treatment. Weight-for-age Z scores at diagnosis were significantly lower in the responders to medical treatment than in the partial or non-responders. Both weight and BMI status increased significantly after the medical treatment in medical responders, but no differences in the partial or non-responders. Weight gain generally alleviates symptoms (2). All but 1 medical responder showed weight gain.

Surgery is warranted in cases of non-responders who have undergone sufficient medical treatment. To date, there has been no scientific data that suggests the appropriate time limit for the duration of medical management or the optimal period before surgery (1, 6). The median durations of medical treatment have been shown to be 9 days (range, 2-62 days) and 65 days (range, 13-169 days) in a pediatric case series (5, 10). In our study, the median duration of treatment was 45 days (range, 18-365 days). The outcomes seemed to be worse when the time limit for the duration of medical treatment exceeded 6 weeks. Although the limitations of present study include the facts that the sample size was small, that some patients were lost to follow-up, and that this was a retrospective study, the results correspond with those of the earlier studies, which reported that patients should have a trial of at least 4 to 6 weeks of conservative treatment with optimal nutritional support before surgery (9).

Associations of SMAS with anorexia nervosa, drug abuse, and other psychiatric disorders have been reported (6, 13, 22-24). These factors can cause malnutrition and weight loss, resulting in a vicious cycle. It is difficult to manage patients with such conditions. In our study, 1 patient with anorexia nervosa responded to initial medical management but deteriorated after 2 months. Therefore, medical treatment should be performed with a multidisciplinary team of psychologists and dieticians.

In conclusion, although low BMI or weight loss is a common predisposing factor for SMAS, this disease often develops in patients with normal BMI or no weight loss. Treatment of SMAS is usually conservative and the success rate is high. The treatment period of >6 weeks may predict poor outcomes in patients treated conservatively. Therefore, medical treatment should be instituted for at least 6 weeks before surgical intervention.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P. Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Dig Surg. 2007;24:149–156. doi: 10.1159/000102097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippl F, Hannig C, Weiss W, Allescher HD, Classen M, Kurjak M. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist's view. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:640–643. doi: 10.1007/s005350200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed AR, Taylor I. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:776–778. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.866.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiu JR, Chao HC, Luo CC, Lai MW, Kong MS, Chen SY, Chen CC, Wang CJ. Clinical and nutritional outcomes in children with idiopathic superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:177–182. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c7bdda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biank V, Werlin S. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in children: a 20-year experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:522–525. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000221888.36501.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merrett ND, Wilson RB, Cosman P, Biankin AV. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnosis and treatment strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Training course on child growth assessment. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Chousleb E, Hidalgo J, Patel S, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y duodenojejunal bypass for superior mesenteric artery syndrome: case reports and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:e344–e347. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31823ba2cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha CD, Alvear DT, Leber DC. Duodenal derotation as an effective treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a thirty-three year experience. Am Surg. 2008;74:644–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TH, Lee JS, Jo Y, Park KS, Cheon JH, Kim YS, Jang JY, Kang YW. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: where do we stand today? J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2203–2211. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozbulbul NI, Yurdakul M, Dedeoglu H, Tola M, Olcer T. Evaluation of the effect of visceral fat area on the distance and angle between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31:545–549. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unal B, Aktaş A, Kemal G, Bilgili Y, Güliter S, Daphan C, Aydinuraz K. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: CT and ultrasonography findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adson DE, Mitchell JE, Trenkner SW. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute gastric dilatation in eating disorders: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:103–114. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199703)21:2<103::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hines JR, Gore RM, Ballantyne GH. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Am J Surg. 1984;148:630–632. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris TC, Devitt PG, Thompson SK. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for superior mesenteric artery syndrome: how I do it. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1870–1873. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bermas H, Fenoglio ME. Laparoscopic management of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 2003;7:151–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal GA, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Multidetector row CT of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:62–65. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802dee64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neri S, Signorelli SS, Mondati E, Pulvirenti D, Campanile E, Di Pino L, Scuderi M, Giustolisi N, Di Prima P, Mauceri B, et al. Ultrasound imaging in diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Intern Med. 2005;257:346–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arthurs OJ, Mehta U, Set PA. Nutcracker and SMA syndromes: what is the normal SMA angle in children? Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e854–e861. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altiok H, Lubicky JP, DeWald CJ, Herman JE. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome in patients with spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2164–2170. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000181059.83265.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CS, Mangla JC. Superior mesenteric artery compression syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;70:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CW, Park MI, Park SJ, Moon W, Kim HH, Kim BJ, Shim IK, Park SS. A case of superior mesenteric artery syndrome caused by anorexia nervosa. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:280–283. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.58.5.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordaan GP, Muller A, Greeff M, Stein DJ. Eating disorder and superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1211. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verhoef PA, Rampal A. Unique challenges for appropriate management of a 16-year-old girl with superior mesenteric artery syndrome as a result of anorexia nervosa: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:127. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]