Abstract

Imatinib, the first-line treatment in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), is generally well tolerated, although some patients have difficulty tolerating the standard dose of 400 mg/day. Adjusting imatinib dosage by plasma level monitoring may facilitate management of patients who experience intolerable toxicities due to overexposure to the drug. We present two cases of advanced GIST patients in whom we managed imatinib-related toxicities through dose modifications guided by imatinib plasma level monitoring. Imatinib blood level testing may be a promising approach for fine-tuning imatinib dosage for better tolerability and optimal clinical outcomes in patients with advanced GIST.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST), Imatinib, Imatinib Plasma Monitoring, Dose-Modification

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of imatinib mesylate (Glivec®/Gleevec®, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) has improved outcomes for patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and imatinib is now considered the standard first-line treatment in patients with metastatic or unresectable GIST (1, 2). Imatinib is generally well tolerated, although some patients have difficulty tolerating the standard dose of 400 mg/day, which may necessitate imatinib dose reductions. However, patients and physicians are cautious and sometimes reluctant to reduce the dose of imatinib because of concerns about disease progression. Indeed, results from a pharmacokinetic analysis suggested that adequate drug exposure, as determined by imatinib plasma trough concentration, is correlated with clinical benefit; a low plasma trough concentration of imatinib (< 1,100 ng/mL) might contribute to reduced efficacy in patients with advanced GIST (3). Previous pharmacokinetic studies also showed that imatinib blood levels have high interpatient variability (3-5) and are affected by several covariates, such as albumin concentration, creatinine clearance, white blood cell count, and major gastrectomy (3, 5). As a result, monitoring imatinib plasma concentration on an individual basis may be important for optimizing clinical outcomes of patients with advanced GIST (6, 7).

Some patients who take the standard dose of imatinib may have abnormally high plasma levels of imatinib due to their individual predisposition to decreased drug metabolism (3-5); it is known that some imatinib-related toxicities may be related to overexposure to the drug (6). The problem becomes even more complicated when these imatinib-related toxicities confound the evaluation of response to imatinib therapy. For example, when patients do not have tumor size reduction and ascites develops as a toxicity of imatinib, this may be misinterpreted as having disease progression and managed with imatinib dose escalation or switching to second-line sunitinib (8). Therefore, adjusting imatinib dosage by plasma level monitoring may help manage patients who experience intolerable toxicities while also achieving sufficient imatinib trough concentrations to maintain efficacy. Here we describe two patients with advanced GIST whose imatinib-related toxicities were successfully managed with dose modifications guided by imatinib plasma level testing.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Patient 1

A 67-yr-old Asian man who presented with intermittent melena and significant weight loss was diagnosed with small bowel GIST with multiple liver metastases and peritoneal seeding on May 25, 2010. He underwent jejunal resection and anastomosis with palliative intent. The excised jejunal GIST measured 7 × 5 × 5 cm and had a c-KIT exon 9 mutation (1,510-1,515 duplication). After surgery, the patient was treated with 400 mg/day imatinib. He had no concomitant medications or co-morbid diseases.

Two months later, the patient developed grade 3 edema, grade 3 ascites, and grade 2 vomiting, with chest radiography revealing layering of a moderate amount of pleural fluid. Because the patient had peritoneal seeding, it was hard to determine whether his ascites and pleural effusion were due to imatinib toxicity or the progression of GIST. Although the follow-up abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the patient's liver metastases had not changed significantly, disease progression was suspected, which prompted a cessation in imatinib treatment and a commencement of sunitinib treatment. The patient was transferred to our hospital for a second opinion after he had been taking sunitinib for approximately 2 months. A thorough review of his previous serial CT scans showed no definitive evidence of disease progression whilst he was on imatinib treatment. We therefore decided to resume 400 mg/day imatinib and use 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT for accurate assessment of response to imatinib treatment.

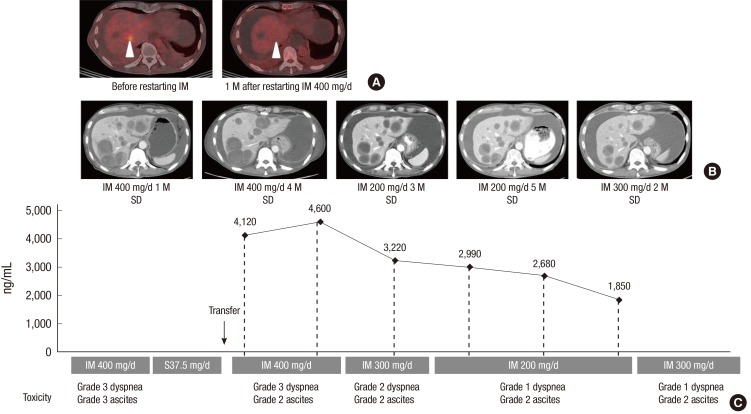

One month after the patient restarted imatinib, a PET/CT scan revealed a significant decrease in maximum standardized uptake value from 4.2 to 2.9 in one of his liver metastases (Fig. 1A and B), suggesting the tumor was responding to imatinib. However, the patient required paracentesis once weekly to control his ascites, and he complained of peripheral edema and dyspnea. Because imatinib blood level testing revealed that the patient had very high imatinib trough plasma exposure, 4,120 ng/mL and 4,600 ng/mL on two different days (Fig. 1C), we decreased his dose to 300 mg/day, which resulted in a steady-state imatinib plasma trough concentration of 3,220 ng/mL (Fig. 1C). However, the patient still had grade 2 edema, ascites, and dyspnea on exertion due to pleural effusion. As his imatinib trough plasma exposure was sufficiently high to achieve an adequate tumor response (3), we further reduced his dose to 200 mg/day. At this dose, his fluid retention, including ascites, edema, and pleural effusion, was greatly improved, and he had no difficulties in daily life; in addition, his liver metastases remained stable (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Imatinib plasma monitoring-guided dose modification reduced toxicities and maintained response in patient 1. A patient with resected small bowel GIST and multiple liver metastases responded to imatinib treatment, as PET/CT scans show a significant decrease in maximum standardized uptake value from 4.2 to 2.9 in one of his liver metastases one month after he restarted imatinib (A; arrow heads). However, the patient had grade 3 dyspnea and grade 2 ascites (C). Serial measurements of imatinib plasma concentration guided imatinib dose modification from 400 mg/day to 300 mg/day and then to 200 mg/day; his liver metastases remained stable (B) and his fluid retention, including dyspnea and ascites, was greatly improved (C). Imatinib dose was increased to 300 mg/day upon patient request; he tolerated ascites and dyspnea (C) and his disease was stable (B). D, day; IM, imatinib; M, month; SD, stable disease.

Five months later, the patient expressed concerns that 200 mg/day of imatinib may be insufficient to control his tumor, as studies have shown that GIST patients with the c-KIT exon 9 mutation may benefit from higher than normal exposure to imatinib (3, 9, 10). We therefore increased his dose to 300 mg/day. He was able to tolerate ascites and dyspnea with the use of regular diuretics but had some limitation of activities. Follow-up CT scans to date showed the patient's disease remained stable (Fig. 1B).

Patient 2

A 69-yr-old Asian man presenting with melena was diagnosed with duodenal GIST and underwent Whipple's operation on May 6, 2004. The excised mass measured 5.5 × 4.5 × 2.0 cm and had a low mitotic rate (< 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields). Mutation analysis showed that the tumor had a KIT exon 11 deletion at amino acid 552. Twenty-two months after surgery, a liver metastasis was detected on follow-up CT scans. The patient was started on imatinib 400 mg/day. The treatment was effective, with a partial response noted after 3 months (Fig. 2A); the treatment was also tolerable, with grade 2 edema the only adverse event experienced by the patient.

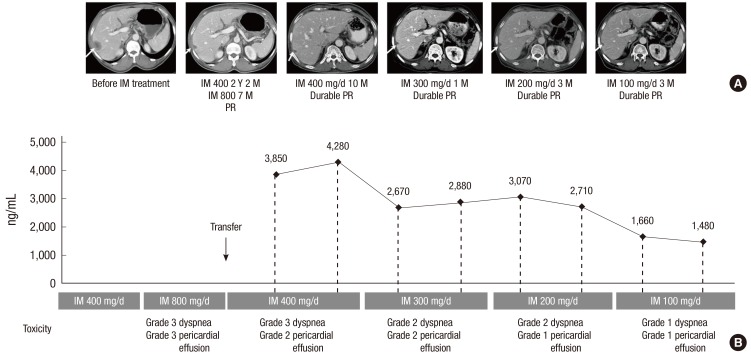

Fig. 2.

Imatinib plasma monitoring.guided dose modification reduced toxicities and maintained response in patient 2. A patient with resected duodenal GIST and a liver metastasis responded to imatinib treatment with a partial response (A; arrows). However, at the standard dose of 400 mg/day, the patient had grade 3 dyspnea and grade 2 pericardial effusion (B). Serial measurements of imatinib plasma concentration guided imatinib dose modification from 400 mg/day to 300 mg/day, 200 mg/day and then to 100 mg/day; his fluid retention (dyspnea and pericardial effusion) was improved (B), with partial response maintained in his liver metastases (A). D, day; IM, imatinib; M, month; PR, partial response; Y, year.

At 26 months following the commencement of imatinib treatment, the patient developed several small, round, mesenteric lymph node enlargements, which were regarded as a sign of disease progression even though the metastatic lesions in his liver remained stable. Imatinib dose was increased to 800 mg/day. After 7 months at this dosage, the patient experienced grade 3 dyspnea and grade 3 pericardial effusion. He was transferred to our clinic for the treatment of these adverse events. However, an in-depth review of his previous serial CT scans by an experienced gastrointestinal radiologist revealed that the morphology of these enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes suggested reactive changes, instead of lymph node metastases, which are rare in GIST (11). The patient was therefore restarted on treatment with 400 mg/day of imatinib. CT scans 10 months later showed that the patient's liver metastasis were stable (Fig. 2A). Although his ascites and pleural effusion gradually improved, the patient complained of dyspnea, and diuretics were required for the control of grade 2 generalized edema. Because imatinib plasma monitoring revealed that the patient had high imatinib plasma trough concentrations (3,850 ng/mL and 4,280 ng/mL on two different days; Fig. 2B), we reduced his dose to 300 mg/day, which resulted in imatinib plasma trough concentrations of 2,670 ng/mL and 2,880 ng/mL (Fig. 2B). However, pericardial effusion was persistently observed, even after his imatinib dose was further decreased to 200 mg/day, which resulted in steady-state imatinib plasma trough concentrations of 3,070 ng/mL and 2,710 ng/mL (Fig. 2B). As the patient's imatinib trough plasma exposure was still sufficiently high (3) and the follow-up CT scan showed that his liver metastasis remained stable (Fig. 2A), we further decreased his dose to 100 mg/day, which resulted in imatinib plasma trough concentrations of 1,660 ng/mL and 1,480 ng/mL (Fig. 2B). To date, the patient has been taking 100 mg/day of imatinib for approximately 1 yr. His fluid retention has improved, with durable partial response in his liver metastasis.

DISCUSSION

Imatinib is metabolized in the liver, predominantly by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 (12). As a result, the plasma concentration of imatinib may be affected by intrinsic variability of CYP enzyme activity and other factors, such as albumin concentration (3, 5). Although studies have assessed the relationship between imatinib plasma concentration and efficacy (3, 4, 12), less is known about the relationship between imatinib plasma concentration and toxicity (6). One study showed that the occurrence and number of side-effects correlated with imatinib total and free plasma concentration in patients with GIST (6). However, the study did not assess imatinib exposure with the grade or type of toxicities, findings that may have been of value in clarifying the dose-dependent toxicities of imatinib.

Here we described two patients who experienced intolerable toxicities while on standard-dose imatinib treatment. Both had high imatinib plasma trough concentrations, which appeared to have contributed to the severe fluid retention (e.g. ascites, edema, and pleural effusion) observed in these patients. Through imatinib plasma monitoring, we reduced the dose of imatinib, consequently decreasing these toxicities, while maintaining sufficient imatinib exposure for adequate efficacy of the treatment.

Another interesting aspect of these two patient cases is that they highlight the difficulties of response evaluation for imatinib therapy in GIST patients. Toxicity of imatinib or reaction to imatinib treatment may sometimes be mistaken for disease progression. For example, in the first patient who had peritoneal metastases, ascites was regarded as a sign of disease progression; in the second patient, enlarged reactive mesenteric lymph nodes were mistaken for lymph node metastatses. Because both patients had no tumor shrinkage in other nodules, which is quite common in patients with advanced GIST on imatinib therapy, it was difficult to determine whether imatinib treatment was effective. 18FDG-PET/CT scan may be considered for accurate assessment of response to imatinib, especially when rapid readout of activity is necessary.

When considering imatinib plasma level monitoring to address intolerable adverse events, it is necessary to also consider covariates that may affect imatinib pharmacokinetics, such as demographics, body weight, and other clinical characteristics. Patients of Asian descent, for example, might display different imatinib pharmacokinetics compared with those of Caucasian descent as a result of different physical characteristics. Whilst there has been no clear elucidation of the influence of race on imatinib pharmacokinetics, several reports have suggested a trend towards lower imatinib trough levels in patients with higher body mass index (3, 5, 13). As such it might be assumed that Asian patients would have a tendency towards lower imatinib trough levels compared to their Caucasian counterparts. However, this assumption should be treated with caution given that the reports were associated with only a weak correlation or tendency towards insignificance. Furthermore, it should also be noted that physical attributes alone are unlikely to explain pharmacokinetic differences between racial backgrounds given potential differences in pharmacogenomics and activity of metabolic enzymes such as CYP3A5. Therefore, in order to individualize treatment with imatinib in patients with GIST, investigation of clinical and demographic covariates correlated with imatinib pharmacokinetics is warranted.

The optimal imatinib exposure level in an individual patient maybe defined as the level that is able to sustain maximal tumour response whilst minimizing adverse events. No reliable evidence exists to define a pharmacokinetic threshold for clinical benefit, though an imatinib plasma trough concentration of less than 1,100 ng/mL has been reported to be related to reduced efficacy in patients with advanced GIST (3). The optimal imatinib exposure level needs to be investigated.

In conclusion, the results of these case reports demonstrate that imatinib plasma monitoring-guided dose modification can successfully manage imatinib-related toxicities due to overexposure without compromising the efficacy of the treatment. Our findings suggest that individual imatinib blood level testing may be a promising approach for fine-tuning imatinib dosage for better tolerability and optimal clinical outcomes in patients with advanced GIST.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Jinling Wu, MD, PhD, for her medical editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Yoon-Koo Kang is a consultant for Novartis, and has received research funding and honoraria for lectures from Novartis. However, the authors are confident that our judgments have not been influenced in preparing this manuscript. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Heinrich MC, Tuveson DA, Singer S, Janicek M, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryu MH, Kang WK, Bang YJ, Lee KH, Shin DB, Ryoo BY, Roh JK, Kang JH, Lee H, Kim TW, et al. A prospective, multicenter, phase 2 study of imatinib mesylate in korean patients with metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Oncology. 2009;76:326–332. doi: 10.1159/000209384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demetri GD, Wang Y, Wehrle E, Racine A, Nikolova Z, Blanke CD, Joensuu H, von Mehren M. Imatinib plasma levels are correlated with clinical benefit in patients with unresectable/metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3141–3147. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng B, Hayes M, Resta D, Racine-Poon A, Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Sawyers CL, Rosamilia M, Ford J, Lloyd P, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imatinib in a phase I trial with chronic myeloid leukemia patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:935–942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoo C, Ryu MH, Kang BW, Yoon SK, Ryoo BY, Chang HM, Lee JL, Beck MY, Kim TW, Kang YK. Cross-sectional study of imatinib plasma trough levels in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors: impact of gastrointestinal resection on exposure to imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1554–1559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widmer N, Decosterd LA, Leyvraz S, Duchosal MA, Rosselet A, Debiec-Rychter M, Csajka C, Biollaz J, Buclin T. Relationship of imatinib-free plasma levels and target genotype with efficacy and tolerability. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1633–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George S, Trent JC. The role of imatinib plasma level testing in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:S45–S50. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Kim TW, Kang HJ, Sohn HJ, Lee JS, Kang YK. Patterns of progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated with imatinib mesylate. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:17–24. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R, Le Cesne A, Schlemmer M, Hohenberger P, van Oosterom AT, Blay JY, Leyvraz S, Stul M, Casali PG, et al. KIT mutations and dose selection for imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Meta-Analysis Group (MetaGIST) Comparison of two doses of imatinib for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis of 1,640 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1247–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong Y, Coit DG, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Lymph node metastasis from soft tissue sarcoma in adults: analysis of data from a prospective database of 1772 sarcoma patients. Ann Surg. 1993;217:72–77. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng B, Lloyd P, Schran H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of imatinib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:879–894. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson RA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, Riviere GJ, Krahnke T, Gathmann I, Wang Y IRIS (International Randomized Interferon vs STI571) Study Group. Imatinib pharmacokinetics and its correlation with response and safety in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a subanalysis of the IRIS Study. Blood. 2008;111:4022–4028. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]