Abstract

Uveitis is caused by disorders of diverse etiologies including wide spectrum of infectious and non-infectious causes. Often clinical signs are less specific and shared by different diseases. On several occasions, uveitis represents diseases that are developing elsewhere in the body and ocular signs may be the first evidence of such systemic diseases. Uveitis specialists need to have a thorough knowledge of all entities and their work up has to be systematic and complete including systemic and ocular examinations. Creating an algorithmic approach on critical steps to be taken would help the ophthalmologist in arriving at the etiological diagnosis.

Keywords: Algorithmic approach, differential diagnosis, naming and meshing, uveitis

Uveitis is caused by disorders of diverse etiologies including wide spectrum of infectious and non-infectious causes. The inflammatory process primarily affects the uveal tissues with subsequent damage to the retina, optic nerve and vitreous. On several occasions, it reflects diseases that are developing elsewhere in the body and uveitis may be the first evidence of such systemic diseases, generating a challenge to the ophthalmologist in reaching the etiological diagnosis. Besides, because several entities share common clinical symptoms and signs, the etiological diagnosis may prove to be a difficult task.[1] Uveitis specialists need to have a thorough knowledge of all entities and their work up has to be complete including systemic and ocular examinations. In addition to the above mentioned challenges, India presents unique problems because of varying socio-economic, demographic and morbidity patterns. The prevalence and severity of diseases in economically deprived population differ from those in rest of the world[2] because of lack of good primary health care, poor affordability and poor compliance. Our ophthalmologist may also have to meet the added challenge of handling these problems in addition to managing uveitis per se The present chapter is to define an algorithmic approach in the diagnosis of uveitis. Algorithms solve problem by showing the critical pathways to be taken. Steps in building an Algorithm include the following:

Defining the problem and deriving a clinical diagnosis by naming technique given by Nozik.[1]

Reviewing all possible causes of the condition and comparing with existing known uveitis patterns also known as meshing technique.

Proving the diagnosis by presenting diagnostic modalities in a logical manner.

Etiological diagnosis of uveitis starts with the first step of elaborate history followed by systemic examination and ocular examination to reach a clinical conclusion. Subsequently list of differential diagnosis is created in order to decide on laboratory investigations to rule out or rule in the possible etiology. Sometimes other sub specialty consultation may be required such as rheumatologist, infectious disease specialist, pulmonologist or dermatologist.

History Taking

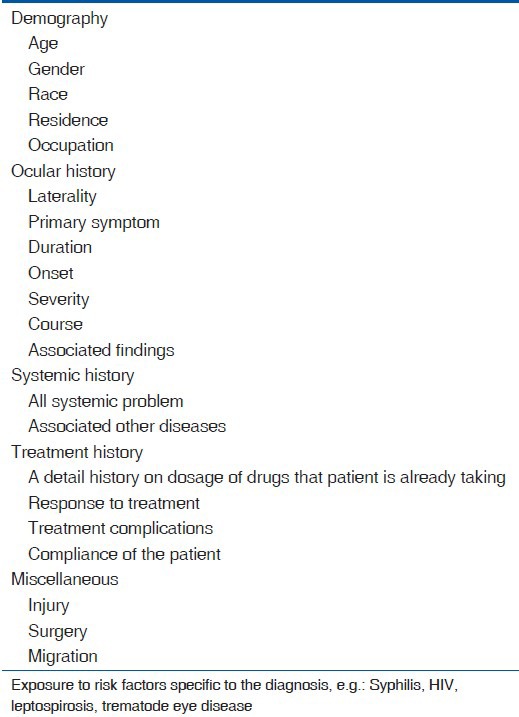

Uveitis work up starts with an elaborate history-taking.[1,3,4,5,6] Subsequently meticulous systemic and ocular examination will offer a clinical conclusion. It is estimated that over 70% of diagnosis can be made on the basis of detailed medical history and thorough clinical work up alone. Systemic history offer possible systemic disease association with ocular involvement. It is often the clinical acumen of the ophthalmologist that points out the diagnosis, that is further confirmed or ruled out by a tailored laboratory approach.[1] Table 1 shows the details that need to be collected for a thorough history taking. Description of each variable is given in detail below.

Table 1.

History in uveitis

Age

Several conditions have a predilection for certain age groups. Juvenile arthopaties and parasitic uveitis are the most common entities in patients younger than 16 years of age.[7] In general uveitis secondary to infections is common in extremes of age and immunological diseases are common in middle age.[2] Some of the examples are:

Children: Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis, Toxocariasis.

Young adults: Behcet's, Human Leukocyte Associated antigen B27– associated uveitis, Fuch's uveitis.

Old age: Vogt Koyanagi Harada's (VKH) syndrome, Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus, Tuberculosis and Leprosy.

Gender

Several conditions have a predilection for specific gender as given below.[2]

Males-Ankylosing spondylitis, Reiters, Behcet's, Sympathetic ophthalmia.

Females-Rheumatoid arthritis, Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Race

Demographic characteristics, such as race and ancestry, can be predispositions to the development of specific conditions, for example:

Ankylosing spondylitis, Reiters – Caucausians.[1]

Sarcoid-Pigmented race.

VKH syndrome, Behcet's syndrome – Orientals.

Socio economic history

Recreational activities such as swimming in open water reservoirs may expose the individuals to water borne diseases that may eventually result in uveitis. The best example is leptospirosis and trematode granulomas. Patients who own dogs or cats or are handlers of these animals may be exposed to the intestinal parasites. Toxoplasma gondii and Toxocara canii occur after ingestion of contaminated food sources or contact with soil. Plumbers and sewer workers are at an increased risk of leptospirosis, which is transmitted by a spirochete in sewage water and urine of rats, cattle or other animals.[8] Some of the examples of zoonotic diseases are:

Cat-Toxoplasmosis.

Dog-Toxocariasis,

Cattle-Leptospirosis, cysticercosis.

Pigs-Cysticercosis, Leptospirosis.

Best examples to be concerned about exposure to risk factors include HIV related ocular disorders, leptospirosis and trematode granuloma in children.[9,10,11,12]

Systemic conditions

Collagen vascular disorders are best examples for non-infectious systemic disease which can cause severe ocular morbidity. Other examples include sarcoidosis, Behcet's syndrome, Reiter's syndrome and VKH syndrome. Tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis are common systemic infections that can cause uveitis.[11] Other recently reported systemic infections such as Chikungunya and West Nile Virus diseases can also cause ocular inflammation.[13,14] Endogenous endophthalmitis is more common in diabetics, renal failure and immuno suppressed patients. In addition patients who received intravenous fluid prior to onset of uveitis may also suffer from endogenous endophthalmitis.

Ocular symptoms

Pain, redness and photophobia are the important symptoms for anterior uveitis, while floaters with or without decrease in vision is important for intermediate and posterior uveitis. Pain on ocular movement is seen in posterior scleritis or in orbital inflammatory diseases. Sudden bilateral loss of vision would indicate either VKH's syndrome or Sympathetic ophthalmia.[2,3,4,5]

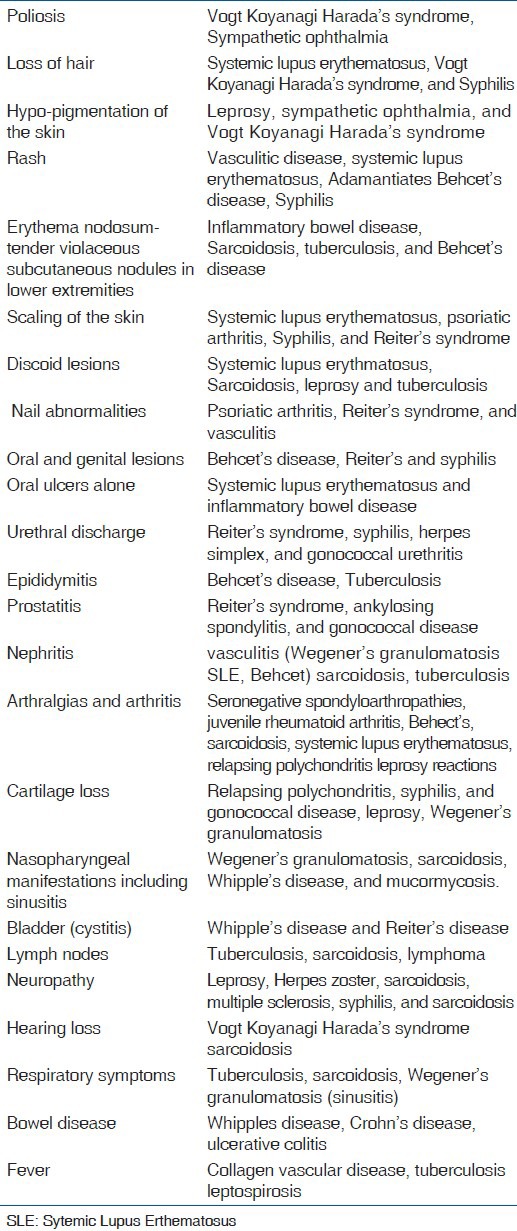

Extraocular Examination

The physical signs of extra ocular disease can add evidence to support the etiological diagnosis. Frequently, the findings may have escaped recognition by the patient or, if recognized, may have been deemed insignificant. Thus, it is important for the ophthalmologist to routinely evaluate patients for evidence of extra ocular disease. Table 2 gives some examples of systemic clinical signs one may see in specific uveitis cases.

Table 2.

Systemic signs

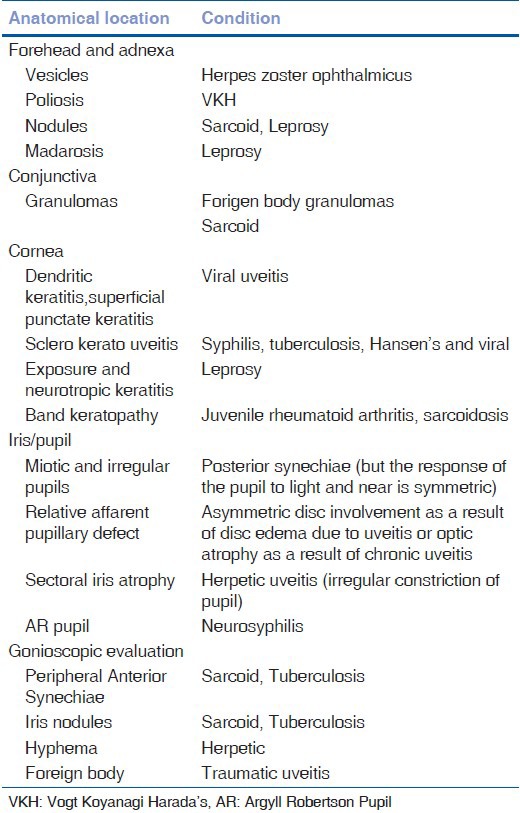

Ocular Examination

A comprehensive eye examination is a requirement for all patients with uveitis, beginning with an assessment of the patient's best-corrected visual acuity. A good day light examination and external examination with torch light is essential in every patient. Often clues on infectious diseases like Hansen's disease or Herpes can be obtained on adnexal examination. Common ocular signs that help in the diagnosis are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ocular signs

Conjunctiva, episclera, sclera and pupillary examination

Examination of the anterior surface of the eye should first be performed in ambient illumination for subtle color differences. Inflammation of the conjunctiva and episclera appear bright red in daylight and more in the fornix. In cases of uveitis, the congestion of the perilimbal area is more than the palpebral and forniceal conjunctiva. Scleritis will present with dilation of deep vascular plexus which is better seen with red free illumination with tenderness on palpation. Examination of pupil gives clue regarding some of the etiological conditions and structural alterations as a result of inflammation.[1]

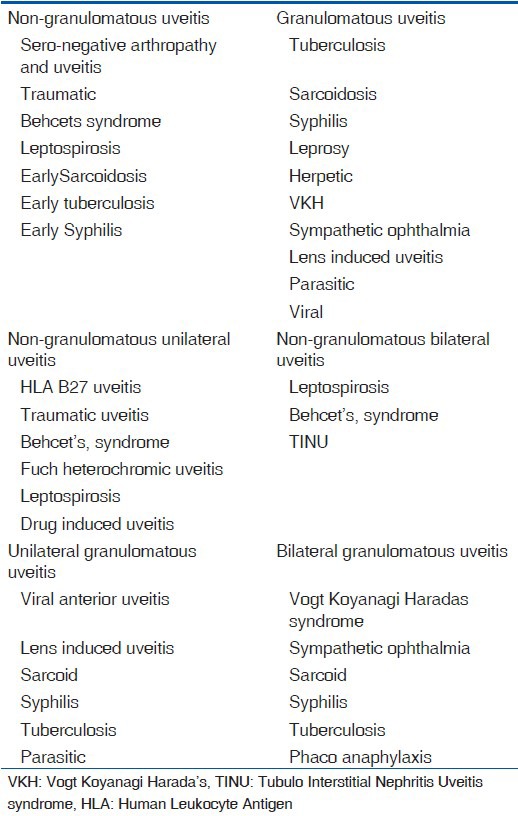

On slit lamp examination, uveitis can be classified either as granulomatous or non-granulomatous [causes mentioned in Table 4]. Rarely keratic precipitates (KP) may be uniformly distributed as seen in Fuch's uveitis, Possner Schlossman syndrome, sarcoid uveitis and lens induced uveitis.

Table 4.

Causes of non-granulomatous and granulomatous uveitis

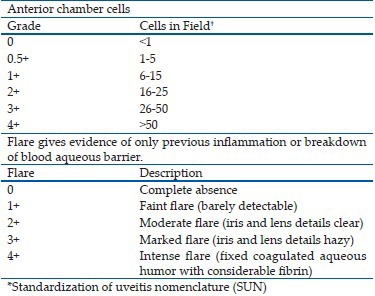

Anterior chamber reaction

The presence of cells and flare in the anterior chamber is a marker for inflammation of iris and ciliary body. The field size recommended for examination is a slit beam of 1 mm by 1 mm for the grading of anterior chamber cells and flare.

The SUN* Working Group Grading Scheme[15] for anterior chamber cells and flare:

Iris

Examination of iris may include the presence of posterior synechiae which when extensive may produce seclusio pupillae, sometimes leading to formation of iris bombe and angle-closure glaucoma. Iris atrophy is a diagnostic feature of herpetic uveitis. Varicella zoster virus generally produces sector iris atrophy due to a vascular occlusive vasculitis, whereas herpes simplex virus usually produces patchy iris atrophy. Other causes of atrophy include anterior segment ischemia, Hansen's disease, trauma and previous attacks of angle-closure glaucoma. Granulomas may be prominent in the iris stroma or the choroid. Iris nodules are most commonly seen at the pupillary margin are described as Koeppe's nodules whereas those on the surface of iris are called as Busacca's nodules. Sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, VKH syndrome, sympathetic ophthalmia and syphilis can show iris nodules. Normal radial iris vessels can be seen dilated in acute inflammation producing iris hyperemia as in rubeosis irides; however, they disappear when inflammation is controlled. Hetero-chromia of iris can be either hypochromic (abnormal eye is lighter than fellow eye) as seen in Fuch's heterochromic iridocyclitis or hyperchromic (abnormal eye is darker than fellow eye) as seen in melanosis of iris.

Anterior chamber angle

Gonioscopic evaluation may reveal peripheral anterior synechiae sufficient to account for elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Additionally, one may find angle KP, a small hypopyon which was invisible on slit lamp examination, and inflammatory debris, suggesting an additional mechanism of IOP elevation from occlusion of filtering trabecular meshwork. Abnormal iris vessels, neovascularization or fine branching vessels as seen in Fuch's heterochromic iridocyclitis, are easily identified by gonioscopy, and their presence can direct appropriate therapy. In cases in which traumatic uveitis is suspected, angle recession and presence of foreign body may be seen.

Lens

Important lenticular findings include cataract. The most common type of cataract in uveitis patients is the posterior subcapsular opacity. Anterior lens changes may also occur, often in association with lens capsule thickening at a site of iris adhesion. Anterior lens opacities following extreme elevations in IOP (glaukome flecken) provide insight into a history of acute uveitis glaucoma.

Intraocular pressure

The IOP in patients with uveitis is most commonly decreased owing to impaired production of aqueous by the non-pigmented ciliary body epithelium.

The factors that can affect IOP include the accumulation of inflammatory material and debris in the trabecular meshwork, inflammation of the trabecular meshwork (trabeculitis), obstruction of venous return, and steroid therapy.

The causes of elevated IOP include:

Posner-Schlossman's syndrome.

Herpetic uveitis.

Toxoplasmosis.

Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis.

Sarcoidosis.

Iridocyclitis with secondary angle closure glaucoma.

In patients with uveitis, anterior chamber reaction should be assessed before the instillation of fluorescein to prevent obscuration of anterior chamber details due to a greenish hue caused by the dye after penetrating the anterior chamber.

Indirect ophthalmoscopy

When initiating indirect ophthalmoscopy it is important to direct the illumination beam into the patient's eye without the concomitant use of the condensing lens. The red reflex is then evaluated in the primary position. This technique gradually allows the patient's retina to become light-adapted, before exposure to the strong concentrated light delivered by the condensing lens, thereby increasing patient's comfort and cooperation with the examination. More important is the valuable information that the examiner obtains if the quality and nature of the red reflex changes. For example, if there is an area of active chorioretinitis in one quadrant the red reflex is replaced by a yellowish reflex. If a choroidal hemorrhage or tumor is present in a given area the red reflex is dark only in that area. In addition this review of the red reflex may disclose highly elevated masses as well as intravitreal changes such as foreign bodies, membranes, and parasites.

Vitreous

In active vitritis, cells appear white and are evenly distributed between the liquid and formed vitreous. Old cells are small and pigmented, whereas debris tends to be pigmented but larger in size. Active cells can be found in locations that can be helpful diagnostically. A localized pocket of vitritis may suggest underlying focal retinal or retinochoroidal disease. Focal accumulation of inflammatory cells around vessels is seen in active retinal vasculitis. Inflammatory cells that accumulate in clumps (snow balls) may precipitate on to the inferior peripheral retina as seen in intermediate uveitis, associated with sarcoidosis. Cells may accumulate in the retrovitreal space following contraction of vitreous fibrils and posterior vitreous detachment.

Pars plana

Examination of the peripheral retina and pars plana for snowbanking usually requires scleral depression or use of a three-mirror Goldmann contact lens. Exudation, fibroglial band formation and revascularization are pathologic processes that occur at the pars plana.

Retina and choroid

Retinitis presents with a yellow-white appearance and poorly defined edges, often associated with hemorrhage and exudation. Involvement may be focal or multifocal. Retinal vasculitis is usually seen in retinitis and may be seen in Wegener's granulomatosis, Systemic Lupus Erythmatosus, viral retinitis including herpitic group of infections or newly recognized viruses including Chikungunya or West Nile virus infections[14,15] Phlebitis may be seen in Leptospirosis or Sarcoidosis.

Choroidal inflammation can also be focal or multifocal. It is not frequently associated with vitritis due to intact retinal pigment epithelial cells that prevents inflammatory cell migration. The inflamed choroid may appear thickened and prominent infiltrates and granulomas may be present. Decomposition of the retinal pigment epithelium can alter the permeability of the blood-ocular barrier, resulting in retinal detachment. It should be highlighted that tuberculosis and sacoidosis can cause both focal and multifocal choroiditis.

Optic disc

Optic disc inflammation can occur with or without other signs of uveitis. Optic disc involvement takes the form of papillitis or disc edema, neovascularization, infiltration, and cupping. Neovascularisation occurs in ischemic states and is characterized by fragile vessels that are easily ruptured. Sarcoidosis and leukemia can infiltrate the disc tissue, producing an appearance similar to papillitis. Optic neuritis can occur in multiple sclerosis.

Macula

Chronic inflammation can lead to the following pathologies at macula

Cystoid Macular Edema.

Macular lamellar holes.

Retina Pigment Epithelial clumping.

Choroidal Neo-Vascular Membrane

Exudative macular detachment.

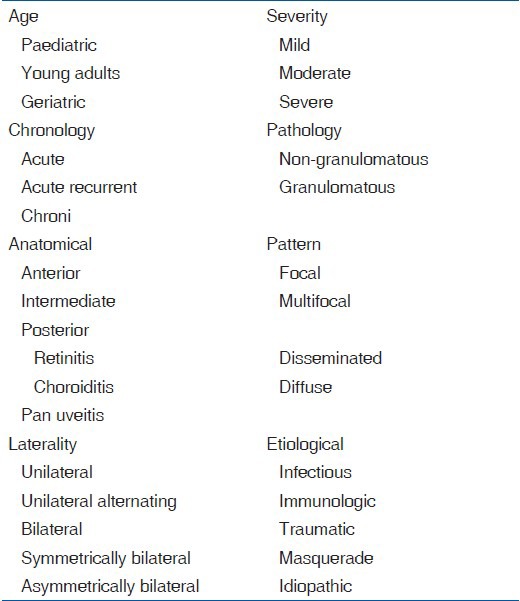

Systematic Work Up

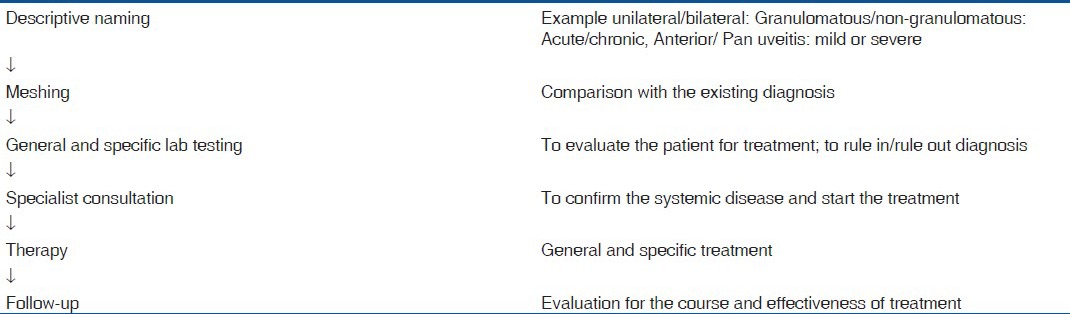

Once history is taken and complete systemic examination is done, a specific name can be assigned to the clinical entity by using a set of descriptive terminologies in uveitis[1] [Table 5]. Descriptive name can now be compared to the known uveitis patterns. The above two steps are known as “Naming and Meshing Step.”[1]

Table 5.

Descriptive terminologies in uveitis

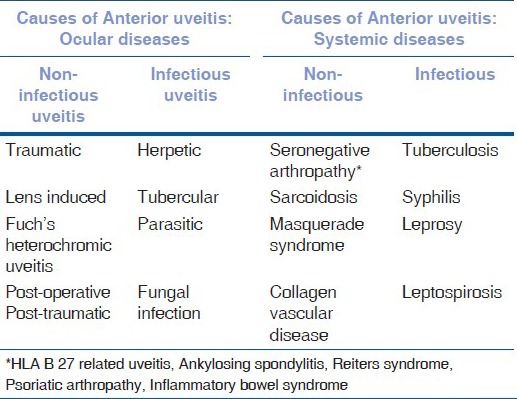

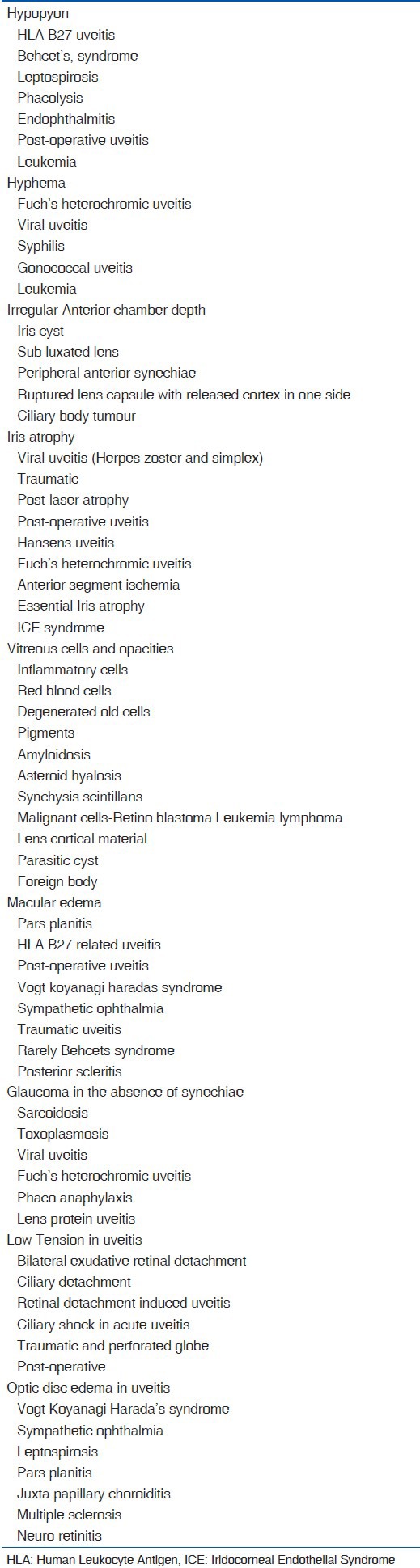

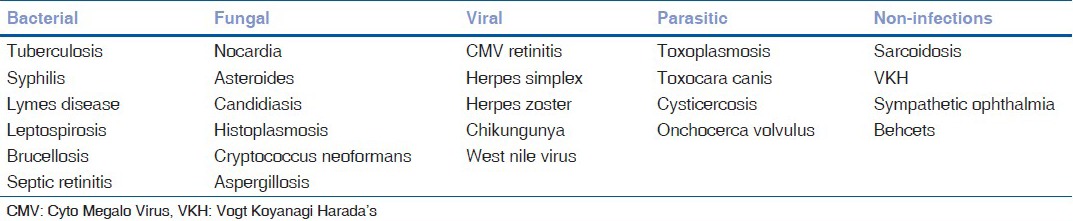

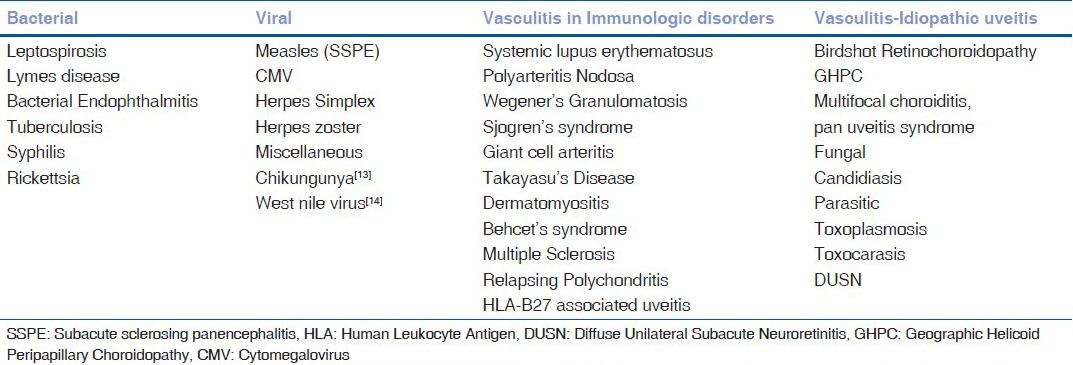

Probable list of etiologies or causes [Table 6a–e] are constructed and this is known as differential diagnosis (DD). After arriving at a DD we look for investigations to confirm or rule out the specific diagnoses. Table 7 is an algorithm showing systematic workup in uveitis. A comprehensive work up takes the clinician to the list of differential diagnosis [Table 8] and then to a laboratory work up before the treatment is finalised.

Table 6a.

Causes of Anterior uveitis

Table 6e.

Causes of joint pain in ocular inflammation

Table 7.

Systematic work up

Table 8.

Differential diagnosis of various clinical signs in uveitis

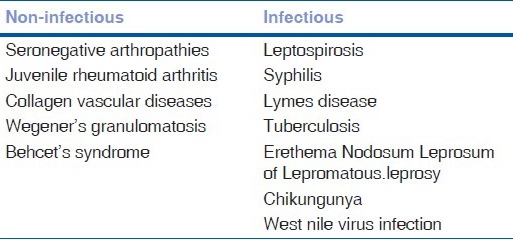

Table 6b.

Causes of posterior uveitis and pan uveitis

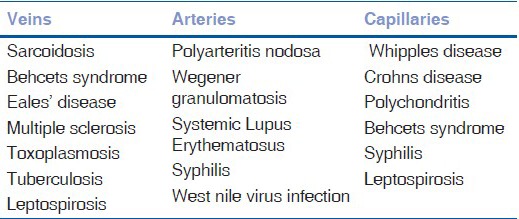

Table 6c.

Causes of retinal vasculitis

Table 6d.

Causes of retinal vasculitis according to size of vessels

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge Dr. Rathika, Aravind eye hospital, and Dr. Tulika Kar, Dehra Dun for their patient assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Smith RE, Nozik RA. 2. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1986. Uveitis: Goals of Uveitis Management; A clinical approach to diagnosis and management; pp. 23–24. Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rathinam SR, Namperumalsamy P. Global variation and pattern changes in epidemiology of uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:173–83. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.31936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham ET, Nozik RA. Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology. Vol. 37. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. Uveitis: Diagnostic approach and ancillary analysis; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussenblatt RB, Whitcup SM, Palestine AG. Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. Examination of the patient with uveitis; pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao NA, Forster DJ, Aigsburger JJ. The Uvea: Uveitis and Intraocular Neoplasms. Vol. 2. New York: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992. General approach to the uveitis patient; pp. 2.1–2.18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper SL, Chorich LJ, Foster CS. Diagnosis of uveitis. In: Foster CS, Vitale AT, editors. Diagnosis and Treatment of Uveitis. Philadelphia: W B Saunders; 2002. pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham ET., Jr Uveitis in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8:251–61. doi: 10.1076/ocii.8.4.251.6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathinam SR. Ocular leptospirosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:381–6. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inungu J, Lewis A, Mustafa Y, Wood J, O’Brien S, Verdun D. HIV Testing among Adolescents and Youth in the United States: Update from the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Open AIDS J. 2011;5:80–5. doi: 10.2174/1874613601105010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajapure V, Tirwa R, Poudyal H, Thakur N. Prevalence and risk factors associated with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in Sikkim. J Community Health. 2013;38:156–62. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shukla D, Rathinam SR, Cunningham ET., Jr Leptospiral uveitis in the developing world. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:113–24. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181d2df58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathinam SR, Usha KR, Rao NA. Presumed trematode-induced granulomatous anterior uveitis: A newly recognized cause of intraocular inflammation in children from south India. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:773–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalitha P, Rathinam S, Banushree K, Maheshkumar S, Vijayakumar R, Sathe P. Ocular involvement associated with an epidemic outbreak of chikungunya virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:552–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla J, Saxena D, Rathinam S, Lalitha P, Joseph CR, Sharma S, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of West Nile virus associated with multifocal retinitis in patients from southern India. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]