Abstract

Nevus of Ota (oculodermal melanosis) is a dermal melanocytic hamartoma with bluish hyperpigmentation along the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve. Extracutaneous involvement, especially ocular, has been reported. A 45-year-old male presented with malignant melanoma of the left orbit in association with nevus of Ota. Being locally invasive, a modified exenteration with frontal flap repair was done on left eye. Adjuvant chemotherapy was given after wound healing. All pigmented lesions of the eye require close monitoring to help in the early diagnosis. Since malignant transformation has been reported in oculodermal melanosis, close follow-up and patient education will facilitate early diagnosis and prompt management. This case is reported for its rarity and unusual presentation.

Keywords: Malignant melanoma, nevus of Ota, orbitotomy

Nevus of Ota (nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, or oculodermal melanocytosis) is a dermal melanocytic hamartoma, mostly congenital, characterized by increased number of melanocytes in the distribution of ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve.[1] In more than half of the patients, this condition is associated with “ocular melanocytosis” involving the conjunctiva, sclera, and uveal tract.[1] Among the ocular complications, orbital melanoma is very rarely reported (0.5%).[1] Here, we describe unilateral malignant melanoma of the orbit associated with nevus of Ota in a South Indian male.

Case Report

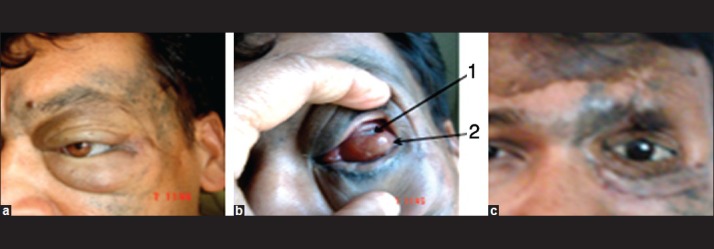

A 45-year-old male, who had a history of diabetes, presented to our department with the complaint of swelling of left eye (LE). He had noticed a gradual increase in the swelling for the last 6-8 months. On examination, LE revealed loss of perception of light, edema of lids, and bluish black pigmentation in the periorbital region and conjunctiva [Fig. 1a]. Ocular motility was restricted in all directions. An irregular mass could be felt through the upper lid, which was fixed to deeper structures. Scar of orbitotomy was seen on the left side. On retraction of the lids, the left eyeball was shrunken and pushed upward by the mass. Only a part of the cornea was visible [Fig. 1b]. He was using scleral shell prosthesis for cosmetic correction. The right eye was normal with a visual acuity of 6/9. Ophthalmoscopic examination of right eye showed few microaneurysms in the macular area. Patient revealed history of bluish black discolouration around the LE, since childhood. Approximately 13 years back, he had noticed protrusion of LE and was diagnosed elsewhere as orbital malignant melanoma. It was managed with lateral orbitotomy for excision biopsy followed by external beam radiotherapy. Later,cosmetic correction with scleral shell prosthesis was given elsewhere, over the phthisical LE. Four years back, in 2005, he attended the Oncology department of Amala Institute of Medical Sciences, for check up. Computerized tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of left orbit showed orbital lesion and he was given Cobalt-60 teletherapy. There was no bony metastasis or extraorbital extension of the lesion as per records.

Figure 1.

(a) Proptosis with artificial eye (January 2009) and cutaneous pigmentation; (b) tumor mass pushing the eyeball upward [arrows (1) part of cornea, and (2) tumor mass covered by conjunctiva]; and (c) posttreatment (February 2011) of LE with prosthesis

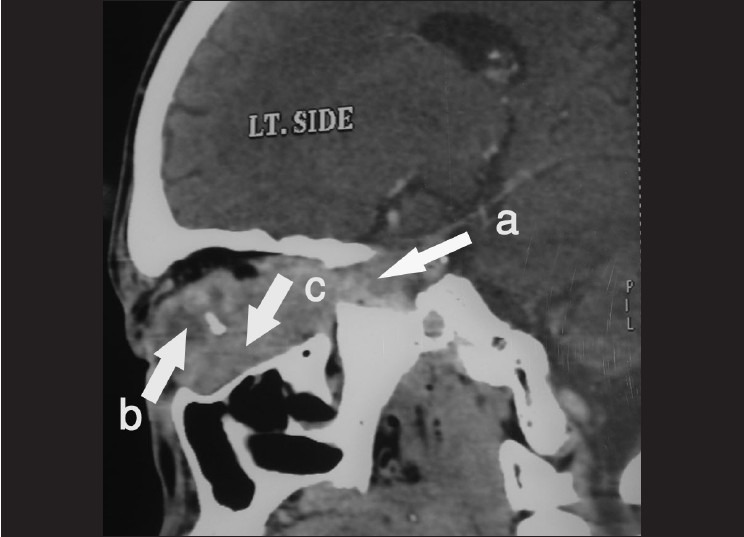

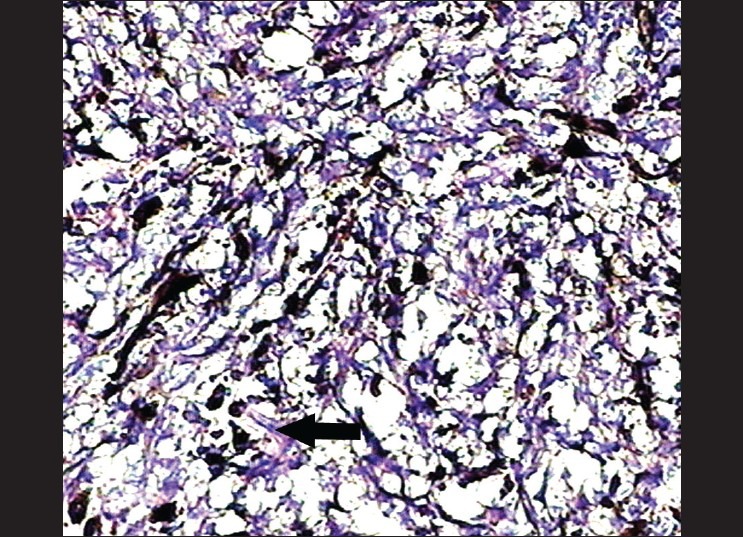

In late 2008, he was referred to us with recurrence of left orbit swelling which gradually increased in size. Repeat CT showed recurrent malignant melanoma in left orbit with extension into the optic canal and lateral wall of orbit [Fig. 2]. The orbit was filled by the pigmented tumor with infiltration into the orbital tissues and periorbita. Histopathology showed a mass of brownish soft tissue measuring 3.5 × 3 × 1.5 cm behind the eyeball. Serial sectioning of the eyeball showed atrophic eyeball. Microscopic examination showed cellular neoplasm arranged in a fascicular pattern composed of spindle cells having prominent nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm [Fig. 3]. Mitotic figures were frequent and cells were laden with dark brown melanin pigment. The eyeball was distorted by the neoplasm. There was infiltration into the optic nerve, orbital muscles, and retrobulbar fibroadipose tissue. In view of the extensive spread of the tumor locally, a modified exenteration with frontal flap repair was done on the left side. Adjuvant chemotherapy was given after wound healing. During follow-up, prosthesis for LE was given [Fig. 1c]. After 1 year of follow-up, the patient did not have any recurrence or metastasis.

Figure 2.

CT scan showing mass lesion in left orbit [arrows (a) retrobulbar extension of the tumor, (b) phthisis bulbi, and (c) tumor mass]

Figure 3.

Histopathology of left orbital tissue showing malignant melanoma (stained by H and E). Arrow shows spindle cells with pigmentation. ×20

Discussion

Nevus of Ota presents as bluish hyperpigmentation of the eyelid and the periocular region. Tympanic membrane, ocular, and nasal mucosa also may be involved. First description of oculodermal melanosis was made by Hulke in 1861. Later, Pusey in 1916 described a case of scleral and facial pigmentation.[1] However, in 1939, Ota from the University of Tokyo coined the name nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmo-maxillaris and melanosis bulbi. Since then, the condition is known as nevus of Ota. It occurs commonly in Asians (0.014–0.034% prevalence) but rarely in Caucasians,[1] with female preponderance.[2] Variable prevalence among different population groups indicates genetic influences.[3] Two peak ages of onset, in early infancy (50%) and in early adolescence, suggested hormonal influence.[3] Even though nevus of Ota is common in the Orientals, malignant transformation is extremely rare.[4] It is still rarer to come across a malignant melanoma which is presenting as a nonchoroidal intraorbital mass.[5] This case presented as proptosis LE, and histopathological analysis showed malignant melanoma.

The cellular origin of the orbital melanoma is not clear.[6] It has been suggested that nevoid cells originate from Schwann cells or other neural elements.[1] Primary orbital tumor arises from orbital melanocytes of neural crest origin.[7] Abnormalities of neural crest migration lead to the development of these congenital dermal melanoses. The exact embryologic events that produce such abnormalities are unknown, but changes in the local embryonic environment could be important. Changes in glycosaminoglycans, which fill the cell free space in early embryologic development, may play an important role in the neural crest migration, leading to dermal melanosis.[1] Exact pathophysiology is not yet known. However, suggested theories include failure of dermal melanocytes to disappear during fetal life, arrested migration of melanocytes in the dermis, and active melanin production by intradermal melanocytes.[5] Choroidal melanomas occur in less than 4% and glaucoma in less than 10% of cases.[3] Primary orbital melanoma has tendency to spread along nerves through the superior and inferior orbital fissures, producing melanocytosis of the contiguous bone and meninges that result in poor prognosis.[7] In this case, there was local spread of the tumor in LE, involving the bone, orbital tissues, and optic nerve resulting in visual loss. Patients should be examined carefully to note deep cutaneous pigmentation. Specific malignant conversion rates have not been recorded, but follow-up is particularly essential in Caucasian patients, where complications are frequent.[5] Any suspicious clinical change of malignant transformation warrants biopsy.[5] Regardless of the race, greater chances are there to develop malignant melanoma within one of the affected tissues in patients with the nevus of Ota.[3]

Koranyi et al. (2000) have reported a better prognosis in a case with short history and early treatment.[8] In this case, the patient had a long drawn out course with intervals of nonsurveillance, which increased the chances for the local spread of the tumor. Primary orbital melanoma is usually well circumscribed, as demonstrated in CT scan.[9] If circumscribed, local excision of the tumor may be done by orbitotomy with preservation of the eye.[9] The management of melanoma of the eye and orbit is still controversial.[9] The management will depend on the stage of presentation. Ideally, the lesion should be removed as a whole with adequate clearance. In this patient, the prognosis would have been better if the lesion was excised as a whole, in the early stage. This would have helped in preserving vision. If the excised margins are not free from neoplasm, appropriate radiotherapy or chemotherapy may have to be instituted. Frequent follow-up and proper education of the patient regarding the condition also should be done. With prolonged history, existing lesion can undergo occult malignant changes, as evidenced in this case.

To conclude, this was a rare case with malignant transformation in oculodermal melanosis, which warrants close follow-up and patient education. This would facilitate early diagnosis of malignant transformation. The timely intervention could improve prognosis and outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable help of Dr. Ajith TA, Associate Professor, Department of Biochemistry during the preparation of the article and the staff of Pathology Department, Amala Institute of Medical Sciences, for the histopathological analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Henry HL, Chan MB, Kono T. Nevus of Ota: Clinical Aspects and Management. Skin Med. 2003;2:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lui H. Nevus of Ota and Ito. [Last accessed on 2011 Jan 14]. Available from: http://emed.com .

- 3.Sharan S, Grigg JR, Billson FA. Bilateral naevus of Ota with choroidal melanoma and diffuse retinal pigmentation in a dark skinned person. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1529–45S. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.070839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh M, Kaur B, Annuar NM. Malignant melanoma of the choroid in a naevus of Ota. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:131–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John H, Britto JA. Nonchoroidal intraorbital malignant melanoma arising from naevus of Ota. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:387–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loffler KU, Witschel H. Primary malignant melanoma of the orbit arising in a cellular blue naevus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:388–93. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albert DM, Miller JW, Jakobiec FA. 3rd ed. Vol. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders & Co; 2000. Albert & Jakobiec's Principles & Practice of Ophthalmology; pp. 3238–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koranyi K, Slowik F, Hajda M, Banfalvi T. Primary orbital Melanoma associated with Oculodermal melanocytosis. Orbit. 2000;19:21–30. doi: 10.1076/0167-6830(200003)1911-zft021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peckham M, Pinedo H, Veronesi U. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. Oxford Textbook of Oncology; pp. 941–2. [Google Scholar]