Abstract

Despite significant advancements in medical and device-based therapies, cardiovascular disease remains the number one cause of death in the United States. Early detection of atherosclerosis, prevention of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death, and modulation of adverse ventricular remodeling still remain elusive goals. Molecular imaging focuses on identifying critical cellular and molecular targets and therefore plays an integral role in understanding these biological processes in vivo. Since many imaging targets are upregulated before irreversible tissue damage occurs, early detection could ultimately lead to development of novel, preventive therapeutic strategies. This review addresses recent work on radionuclide imaging of cardiovascular inflammation, infection, and infarct healing. We further discuss opportunities provided by multimodality approaches such as PET/MRI and PET/optical imaging.

Keywords: molecular imaging, cardiovascular, nuclear medicine, multi-modality, MRI

Despite recent advances in diagnosis, treatment, and guideline-based management, cardiovascular disease remains the number one cause of death in the United States. Consequently, there is a strong impetus for shifting from late-stage diagnosis and in-hospital care to detection of subclinical disease and prevention. Molecular imaging is positioned to play a key role in this transition by addressing challenges such as identification of vulnerable plaque and assessment of post-infarction ventricular remodeling. Our objective in this focused review is to update the reader on the most recent advancements in the field of nuclear cardiovascular imaging of inflammation, infection, and infarct healing. We will then look at the road ahead for opportunities afforded by recent developments in multimodality imaging and radioisotope chemistry. Due to space restrictions we refer the reader to earlier in-depth reviews (1–3).

INFLAMMATION

Atherosclerosis

Inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic plaque formation and progression. Key steps involved in the inflammatory cascade include endothelial cell dysfunction, expression of cellular adhesion molecules, lipid retention, monocyte recruitment and differentiation into macrophages, foam cell formation, proteolysis, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. Ultimately, the plaque erodes and ruptures, leading to arterial thrombosis and myocardial infarction or stroke. All of these processes serve as potential targets for the development of molecular imaging probes that detect disease at a time point when intervention can prevent irreversible damage (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Imaging and the ischemic cascade.

Schematic representation of disease progression. Plaque rupture and coronary thrombosis represent the inflection point. A) PET/CT of VCAM-1 expression (4); B) PET/CT of macrophages (5); C) SPECT/CT of MMP (7); D) intracoronary optical coherence tomography(courtesy of Kevin Croce); E) thrombotic occlusion of a coronary artery(reproduced with permission from British Medical Journal publishing group); F) tagging MRI (own data); G) angina pectoris (reproduced with permission from American Medical Association); H) late gadolinium enhancement MRI showing myocardial infarction (own data).

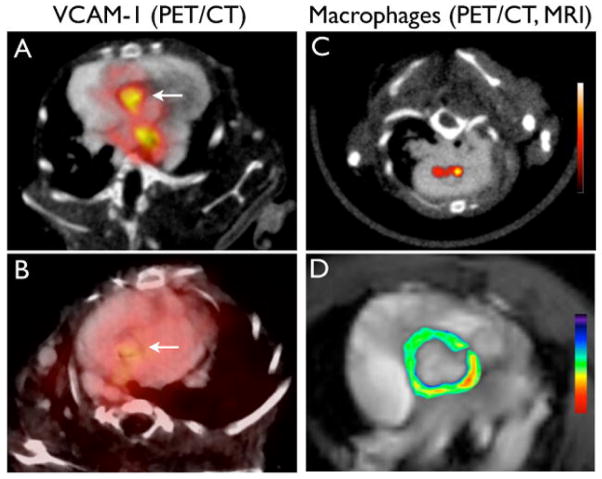

Expression of adhesion molecules on activated endothelial cells is one of the first steps in the inflammatory cascade and facilitates recruitment of monocytes into plaque. Agents that target adhesion molecules may be particularly suited to detecting early atherosclerotic lesions. We developed an 18F-labeled vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 ligand, 18F-4V, and demonstrated the feasibility of imaging VCAM-1 expression by PET-CT in a murine model of atherosclerosis (4). 18F-4V detected nascent lesions and measured differences in VCAM-1 expression caused by statin treatment (Figure 2A). Dextranated magnetofluorescent nanoparticles are rapidly ingested by macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques and therefore report on a more downstream target (5). Cross-linked iron oxide particles were labeled with 64Cu (64Cu-CLIO), thereby permitting PET and MRI sensing of macrophage content within the plaque (Figure 2B). Another approach towards macrophage imaging targets proteins on mononuclear phagocytes. PK11195 is a selective ligand for the peripheral benzodiazepene receptor (PBR), a translocator protein expressed on activated macrophages. Gaemperli et al. (6) imaged 32 patients with carotid stenosis with the PET agent 11C-PK11195 and found that symptomatic carotid plaques had high target-to-background ratios (TBR).

Figure 2. Targeted imaging of atherosclerosis.

(A) 18F-4V PET/CT of VCAM-1 expression (4). Higher uptake is seen in ApoE−/− mice as compared to statin-treated mice (B). (C) Nanoparticle PET/CT of macrophages (5). (D) MRI with pseudocolored T2 signal intensity which decreased due to accumulation of iron oxide nanoparticles.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) promote plaque instability. Fujimoto and colleagues used a radiolabeled (99mTc) MMP inhibitor to non-invasively quantify MMP activity in atherosclerotic lesions in mice (7). The same group also imaged atherosclerotic lesions in rabbits (8) to quantify the effect of dietary modification, as well as statin therapy, on plaque MMP activity. Increasingly, imaging approaches examine multiple biological processes at the same time to gain broader perspective on disease progression. Haider et al. pursued dual molecular imaging using radiolabeled metalloproteinase inhibitor and the annexin probe AA5 (9). MMP and apoptosis signals correlated with each other (r=0.6, p<0.001) and were significantly higher in rabbits on high cholesterol diet as compared to those on normal diet or treated with statin.

Length and cost of traditional clinical endpoint studies have created an interest in using molecular imaging to study therapeutic efficiency. The Fayad group first optimized 18FDG PET protocols (10) and then applied them in the dal-PLAQUE trial. This multi-center clinical trial used 18FDG PET/CT and MRI to assess structural and inflammatory indices as clinical end-points (11). Patients were randomly assigned to placebo or to therapy with a cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitor. This trial provided interesting links between HDL level, vascular inflammation, and subsequent structural vascular changes.

Arterial Aneurysms

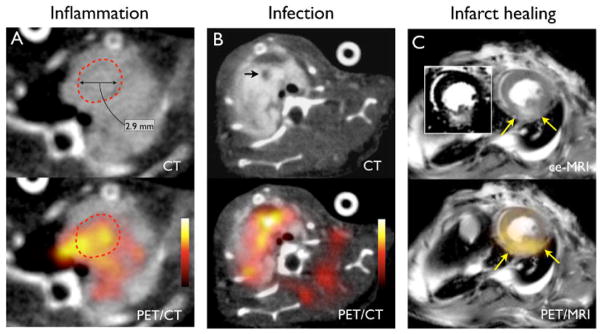

Inflammation has been implicated in aneurysm formation, dilation and rupture. While there is only a moderate correlation between aneurysm size and risk of rupture, it is plausible that inflammatory activity in the vessel wall may be more predictive of rupture. We employed a macrophage-targeted nanoparticle labeled with 18F for PET/CT in ApoE−/− mice with aneurysms (12) and found that the PET signal was increased in progressing aneurysms (Figure 3A). Another strategy targeted MMP activity in the vessel wall (13). Razavian et al. examined carotid aneurysms in ApoE−/− mice exposed to calcium chloride using RP782, an 111In-labeled tracer with specific activity for activated MMPs. Focal uptake of RP782 in carotid arteries peaked at 4 weeks after aneurysm induction. Once translated, these approaches could enable individualized risk-stratification and development of new decision algorithms based on pathobiology rather than anatomy.

Figure 3. Vascular inflammation, infection, and infarct healing.

(A) Macrophage-targeted PET/CT of inflammation in aortic aneurysm with 18F-CLIO (12). Dotted circle outlines the aneurysm in the ascending aorta. (B) PET/CT of S. aureus endocarditic vegetation (arrow) in mice with 64Cu-ProT(14). (C) Hybrid PET/MRI of murine post-infarction inflammation with a macrophage-targeted 64Cu-labeled nanoparticle (own unpublished data). The infarct area is detected by late gadolinium enhancement on MRI (insert, arrows).

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Detection and management of infective endocarditis remains challenging as standard diagnostic criteria, such as fever or new heart murmur, lack sensitivity and specificity. While helpful, most echocardiographic findings are manifest at late stages of disease and cannot inform on the infective activity in vegetations. Targeted molecular imaging aimed at visualizing bacteria or their products in vegetations may lead to earlier and more reliable diagnosis and can help to find septic emboli. We developed an agent for identifying staphylococcal infections by targeting staphylocoagulase, a virulence factor secreted by Staphylococcus aureus (14). An engineered prothrombin analog detected endocarditis vegetations via noninvasive fluorescence and PET imaging in a mouse model (Figure 3B). In contrast to blood cultures that detect circulating bacteria, the agent reported on the type and activity of bacteria in vegetations.

MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION AND VENTRICULAR REMODELING

With increased infarct survival, there has been a rise in number of patients with heart failure. Identifying predictors of adverse ventricular remodeling may help further risk stratification of patients and open novel therapeutic avenues. Molecular imaging of cell death, inflammatory response, angiogenesis, and fibrosis, have all pursued deeper understanding of the remodeling process.

Injury to the myocardium results in an acute inflammatory response dominated by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system (15). Similar to the strategy used for inflammatory atherosclerosis, 18FDG PET imaging was employed to assess inflammation following ischemic myocardial injury (16, 17). Berr et al. followed ischemia-reperfusion injury with serial PET and MRI in a murine and found increased 18FDG uptake on day 7 post MI (16). While the 18FDG signal in acute murine infarcts mainly derives from inflammatory cells (17), the high myocyte uptake of 18FDG and the ischemia-induced shift in myocardial metabolism towards glycolysis pose challenges in interpretation, especially if infarct tissue and surviving myocardium are interspersed.

Angiogenesis provides an interesting target for non-invasive molecular imaging of wound healing. Rodriguez-Porcel et al. developed a PET tracer, 64Cu-DOTA-VEGF121, to image in vivo VEGF receptor expression in rats with MI (18). Serial imaging demonstrated that the VEGF receptor expression level increased significantly after MI and remained elevated for 2 weeks. RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartate), a binding motif for integrins, serves as affinity ligand for αv β3-integrin targeted probes. Sadeghi and Bender first studied αv β3-integrin SPECT imaging in a vascular injury model in ApoE−/− mice with RP748, an 111In -labeled peptidomimetic with affinity for αv β3-integrin (19). The same group then imaged hypoxia and angiogenesis in parallel using 99mTc-BRU59-21 and 111In-RP748 in rodent and canine models of MI (20). These studies demonstrated the prospect of noninvasive tracking of hypoxia-induced integrin activation as a marker of angiogenesis.

Immune cells recruited to the injured myocardium secrete cytokines proteolytic enzymes that play an important role in the healing process. In particular, MMPs accelerate LV remodeling by digesting extracellular matrix, and probes targeting MMPs can follow these processes after MI. Su et al. assessed temporal changes in MMP activation after MI with a broad MMP-targeted agent, 111In-RP782, in a murine model (21). More recently, MMP-targeted SPECT/CT imaging followed post-infarct remodeling in a porcine model using 99mTc-labeled RP805 (22). Increased agent retention was seen throughout the heart early post-MI, and the signal remained elevated for one month.

MULTIMODALITY IMAGING

Multimodality imaging combines individual strengths of different modalities and offers integrated molecular, physiologic, and anatomic information. In addition, by incorporating complimentary agents, hybrid imaging permits simultaneous evaluation of several disease pathways. Hybrid PET/MRI may be particularly useful for following molecular and cellular events after MI. We labeled a macrophage-targeted nanoparticle with 64Cu to pursue PET/MRI in a mouse 3 days after MI. Delayed enhancement MRI after injection of Gd-DTPA delineated the infarcted myocardium, while the PET signal reflected inflammatory cells which ingested the nanoparticles (Figure 3C, unpublished data). We speculate that this signal could represent a key wound healing process -- removal of necrotic tissue -- and may predict outcome. The concept could be expanded further by adding a molecular MRI agent to trace two biological targets simultaneously.

Hybrid PET/optical reporter imaging may also have a role in a staged diagnostic/therapeutic approach. A potential scenario for managing patients with atherosclerosis could use the PET isotope on a macrophage-targeted nanoparticle to localize inflamed plaque and decide whether invasive intervention is necessary. In a second step, the fluorochrome attached to the same nanoparticle could guide local therapy while detected with a fluorescence sensing intravascular catheter (23).

Finally, multimodal techniques already routinely guide imaging agent development. Especially with larger probes such as nanoparticles or proteins, derivatization with fluorochromes allows initial screening with optical techniques such as fluorescence tomography, fluorescence reflectance imaging, fluorescence histology, and flow cytometry (24). Once a lead preparation is identified, one can then move on to more time consuming and expensive nuclear imaging, thus accelerating the throughput of the probe discovery process. These approaches are enhanced by bioorthogonal coupling reactions that enable modular attachment of radionuclides and fluorochromes to imaging probes (25). Cycloaddition reactions, often referred to as “click” chemistry, also permit modular labeling of small molecules with commonly used PET isotopes such as 18F.

CONCLUSION

There is a need for early non-invasive detection of atherosclerosis as well as imaging of processes that promote adverse ventricular remodeling. Multimodality molecular imaging has become part of the toolbox in basic science. A major goal for realizing the true impact of imaging on clinical care is to accelerate the movement of imaging probes through the regulatory approval process. The road ahead for molecular imaging is promising, but many miles need to be covered to establish the comparative (cost-) effectiveness of such strategies and to integrate them into clinical decision making.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the NIH (R01HL095629, R01HL096576, Translational Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology HHSN268201000044C). We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Drs. Weissleder and Libby.

References

- 1.Dobrucki LW, Sinusas AJ. PET and SPECT in cardiovascular molecular imaging. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadeghi MM, Glover DK, Lanza GM, et al. Imaging atherosclerosis and vulnerable plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51 (Suppl 1):51S–65S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer CM, Sinusas AJ, Sosnovik DE, et al. Multimodality imaging of myocardial injury and remodeling. J Nucl Med. 2010;51 (Suppl 1):107S–121S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Panizzi P, et al. 18F-4V for PET-CT imaging of VCAM-1 expression in atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:1213–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahrendorf M, Zhang H, Hembrador S, et al. Nanoparticle PET-CT imaging of macrophages in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2008;117:379–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaemperli O, Shalhoub J, Owen DR, et al. Imaging intraplaque inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis with 11C-PK11195 positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Eur Heart J. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr367. First published online September 19, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto S, Hartung D, Ohshima S, et al. Molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase in atherosclerotic lesions: resolution with dietary modification and statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohshima S, Petrov A, Fujimoto S, et al. Molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase expression in atherosclerotic plaques of mice deficient in apolipoprotein E or low-density-lipoprotein receptor. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:612–617. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haider N, Hartung D, Fujimoto S, et al. Dual molecular imaging for targeting metalloproteinase activity and apoptosis in atherosclerosis: molecular imaging facilitates understanding of pathogenesis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, et al. Atherosclerosis inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET: carotid, iliac, and femoral uptake reproducibility, quantification methods, and recommendations. J Nucl Med. 49:871–878. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fayad ZA, Mani V, Woodward M, et al. Safety and efficacy of dalcetrapib on atherosclerotic disease using novel non-invasive multimodality imaging (dal-PLAQUE): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1547–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61383-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Marinelli B, et al. Detection of macrophages in aortic aneurysms by nanoparticle positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:750–757. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razavian M, Zhang J, Nie L, et al. Molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activation to predict murine aneurysm expansion in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1107–1115. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.075259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panizzi P, Nahrendorf M, Figueiredo JL, et al. In vivo detection of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis by targeting pathogen-specific prothrombin activation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1142–1146. doi: 10.1038/nm.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:2437–2445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berr SS, Xu Y, Roy RJ, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Serial multimodality assessment of myocardial infarction in mice using magnetic resonance imaging and micro-positron emission tomography provides complementary information on the progression of scar formation. Circulation. 2007;115:e428–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.673749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee W, Marinelli B, van der Laan AM, et al. PET/MRI of inflammation in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Cai W, Gheysens O, et al. Imaging of VEGF receptor in a rat myocardial infarction model using PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:667–673. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadeghi MM, Bender JR. Activated alphavbeta3 integrin targeting in injury-induced vascular remodeling. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalinowski L, Dobrucki LW, Meoli DF, et al. Targeted imaging of hypoxia-induced integrin activation in myocardium early after infarction. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1504–1512. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00861.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su H, Spinale FG, Dobrucki LW, et al. Noninvasive targeted imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activation in a murine model of postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 2005;112:3157–3167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahul ZH, Mukherjee R, Song J, et al. Targeted imaging of the spatial and temporal variation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in a porcine model of postinfarct remodeling: relationship to myocardial dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:381–391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.961854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoo H, Kim JW, Shishkov M, et al. Intra-arterial catheter for simultaneous microstructural and molecular imaging in vivo. Nat Med. 2011;17:1680–1684. doi: 10.1038/nm.2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Marinelli B, et al. Hybrid PET-optical imaging using targeted probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7910–7915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915163107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devaraj NK, Weissleder R. Biomedical applications of tetrazine cycloadditions. ACC Chem Res. 2011;44:816–827. doi: 10.1021/ar200037t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]