Abstract

Background

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with poorer health, possibly through activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Purpose

This study aimed to examine the association between SES and catecholamine levels, and variations by acculturation.

Methods

Three hundred one Mexican-American women underwent examination with a 12-h urine collection. Analyses tested associations of SES, acculturation (language and nativity), and their interaction with norepinephrine (NOREPI) and epinephrine (EPI).

Results

No main effects for SES or the acculturation indicators emerged. Fully adjusted models revealed a significant SES by language interaction for NOREPI (p<.01) and EPI (p<.05), and a SES by nativity interaction approached significance for NOREPI (p=.05). Simple slope analyses revealed that higher SES related to lower catecholamine levels in Spanish-speaking women, and higher NOREPI in English-speaking women. Although nonsignificant, similar patterns were observed for nativity.

Conclusions

Associations between SES and catecholamines may vary by acculturation, and cultural factors should be considered when examining SES health effects in Hispanics.

Keywords: Socioeconomic stress, Hispanic, Stress, Acculturation

Introduction

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) is a robust predictor of adverse health outcomes [1]. One of the postulated mechanisms by which SES influences health is via psychological and physiological responses to stress. Specifically, lower SES is posited to predict increased stress and cognitive-emotional distress [1], which in turn trigger a cascade of biological responses [2]. In particular, stress can stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in the release of catecholamines [3]. Whereas acute increases in catecholamine levels may facilitate adaptive stress coping, prolonged increases may promote pathophysiological processes that impair physiological and metabolic functioning [4]. Thus, sympathetic nervous system activation may be an important pathway in SES–health associations, given that low SES has been associated with elevated urinary catecholamine levels [5, 6] and greater risk for cardiovascular [7] and metabolic disorders [8].

The SES–health gradient may not operate consistently across all ethnic groups, and inconsistent, flattened, and positive associations between SES and various health outcomes have been observed in Hispanics [9–12]. Despite disproportionate exposure to adverse social circumstances, Hispanics have longer average life expectancy at birth [13] and lower prevalence rates of myocardial infarction and stroke compared to non-Hispanic whites [14]. Yet Hispanics, especially those of Mexican descent, have higher rates of cardiometabolic disorders (e.g., type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome) compared to non-Hispanic whites [15, 16], which are known risk factors for cardiovascular disease. These epidemiological trends, referred to as the `Hispanic Paradox' [17], have propelled studies aimed at understanding the roles of cultural characteristics in these perplexing findings [18]. Some researchers suggest that acculturation, a bi-dimensional process in which individuals learn and/or adopt certain aspects of the dominant culture while potentially maintaining some or all aspects of their culture of origin, may contribute to the paradox [17]. Within-group comparisons often suggest more favorable health outcomes in lower acculturated Hispanics, as defined by proxies such as nativity, language preference, or duration of US residence [18–20].

Many studies have simultaneously adjusted for SES and acculturation in statistical analyses, or have examined their independent effects. Yet, few studies have considered the interplay between SES and acculturation on Hispanic health. Evidence suggests that the association between SES and health outcomes may vary by acculturation [10, 19]. However, the extent to which acculturation influences sympathetic nervous system activation remains unclear. The purpose of the current study therefore was to assess the relationship between SES and catecholamine levels in a specific Hispanic subgroup (middle-aged Mexican American women residing in San Diego–Mexico border region), and determine variation by acculturation status.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

The current study is part of a larger evaluation of social–cultural factors in cardiovascular disease risk in healthy, middle-aged Mexican-American women living near the San Diego–Mexico border. Participants were randomly recruited via targeted telephone and mail procedures. Women were invited to participate if they were aged 40–65 years, Mexican-American, literate in English or Spanish, and free of major health conditions. Detailed information on the recruitment approach, sample, and method is reported elsewhere [21]. Out of the 321 women in the total sample, 301 had catecholamine excretion data and were included in the current study. There were no differences in education, income, language use, or nativity between those with and without catecholamine data. A significantly larger proportion (12 %) of US-born participants were missing catecholamine excretion data compared to those who were born in Mexico (3.5 %).

Procedures

During the first home visit a bilingual, female research assistant obtained written informed consent, and then gave participants a battery of psychosocial measures (in Spanish or English as preferred), and materials and instructions for an in-home 12-h, overnight urine collection. Participants were instructed to abstain from strenuous exercise and alcoholic beverages for 24 h, and to refrain from smoking for at least 30 min prior to the physical assessment. The following morning, during the second visit and physical assessment, the research assistant recorded the total amount of urine, and placed a small sample in an iced cooler for transportation. At the laboratory, the sample was aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −75°C until the time of assay. The San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego institutional review boards approved all study procedures.

Catecholamines

Assays were performed on a single, integrated sample at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Clinical Biomarker Laboratory. Urinary norepinephrine (NOREPI) and epinephrine (EPI) were measured using a catechol-O-methyltransferase-based radioenzymatic assay that concentrates catecholamines with 81 % efficiency and has inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variability <10 % [17]. Results for NOREPI and EPI were reported in micrograms per gram of creatinine to adjust for body size.

Socioeconomic Status

A composite of education and income was used to capture a continuous representation of SES, such that each one point increase in the composite score is equivalent to a one standard deviation increase in SES. Participants reported their highest level of education, from no education to a doctoral or professional degree. Total monthly family income was assessed on an ordinal scale in $500 increments, ranging from less than $500/month to more than $8,000 per month. Both education and income were recoded into six categories for analysis. Values for education and income were standardized and summed to form the composite, which was in turn standardized, so that each one point increase is equivalent to a one standard deviation higher SES.

Acculturation

Preferred language of survey and self-reported nativity (i.e., country of birth) were used as proxies for acculturation status. Language is a central feature of the acculturation process, has been found to account for high proportion of variance in scores on acculturation measures, and is a commonly used proxy for acculturation status [20]. Nativity is thought to be reflective of length of exposure to the dominant culture [22] and in addition to language, is one of the most commonly used proxies for acculturation status [20]. Those who chose to complete the battery in English were considered more acculturated to US society (coded “1”), relative to those who completed the battery in Spanish (coded “0”). Those who reported that they were born in the USA were also considered more acculturated to US society (coded “1”), compared to those who were born in Mexico (coded “0”).

Covariates

Covariates were chosen based on their conceptual or biological relevance to predictor and outcomes. Menopausal status was assessed via an item that asked participants to indicate whether they had menstruated in the past 12 months, and participants who had not were considered post-menopausal. Depression was assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale Revised (CES-DR; [23]; current sample, α=.91). Exercise levels were assessed with the Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire [24], which asks respondents to state the number of times during a typical week they participated in strenuous or moderate exercise for at least 15 min. The measure provides total Metabolic Equivalent of Task Units (i.e., METs) per week, an estimate of the intensity and energy expenditure of physical activity that is comparable across people of differing body sizes. Average sleep quality over the past month was assessed using the total score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [25]; current sample, (α=.74). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the Quetelet index (kilograms per square meter). Smoking status and use of medications for thyroid disorders were obtained via self-report.

Statistical Analyses

Model assumptions were assessed graphically and analytically. Both NOREPI and EPI were positively skewed, and were normalized via natural-log transformations. All variables were standardized. Ordinary least squares hierarchical multiple linear regression was used to test the relationship between SES, indicators of acculturation (i.e., language and nativity, entered in separate models), and their interaction with each outcome. Covariates were entered first, followed by main effects, then interactions. Model 1 included the main effects of SES, acculturation indicators, and their interactions, adjusting for age. Model 2 added adjustment for thyroid medication, BMI, menopausal status, depression, smoking, sleep quality, and physical activity. Significant SES by acculturation interaction effects that were evident in the full sample were probed via simple slope analyses by computing simple regression lines for the relationship between SES and catecholamines for high (i.e., completed English language survey or born in USA) and low (i.e., completed Spanish language survey or born in Mexico) acculturated groups examined separately. All analyses were conducted using Predictive Analytics SoftWare, Version 18.0 for Macintosh (PASW, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for all study variables. Correlations between SES, acculturation indicators, NOREPI, EPI, and all covariates are also shown. Mean age was 49.7 years (SD=6.5), and the sample was overweight on average (BMI M=28.9; SD=6.3). The majority of women had at least some college (54.1 %), and a monthly income of at least $3,000/month (57.4 %). The majority of the sample preferred Spanish for the assessment language (59.1 %) and was born in Mexico (75.1 %). Higher US acculturation was associated with higher SES (rs=.49, .33 for language and nativity, respectively, ps<.01). English language preference and US nativity were moderately correlated (r=.56, p<.01). As expected, NOREPI and EPI were significantly positively associated (r=.64, p<.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations for study variables

| Variable | M (SD) or N (%) | SES rg | Language r | Nativity r | NE rh | E ri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.7 (6.5) | −.09 | −.05 | −.09 | .13* | .10 |

| Body Mass Index | 28.9 (6.3) | −.14* | .01 | .02 | .00 | −.04 |

| Thyroid medication usea,b | 19 (6.2) | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | .03 | .08 |

| Menopausal statusa,b,c | 152 (47.4) | −.05 | −.10 | −.07 | .19** | .12* |

| Depression | 8.1 (10.7) | −.15** | −.07 | −.08 | .01 | .05 |

| Current smokera,b | 27 (8.9) | −.05 | −.00 | −.02 | .03 | .06 |

| Sleep quality | 4.8 (3.1) | .01 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .02 |

| Exercise (METs/week) | 19.3 (20.5) | .19* | .13* | .05 | −.06 | −.05 |

| Educationa,d | .88** | .40** | .26** | −.09 | −.05 | |

| ≤8th grade | 51 (16.9) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Some high school | 54 (17.9) | – | – | – | – | – |

| GED/high school diploma | 35 (11.6) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Some college | 96 (31.8) | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4-year degree | 48 (15.9) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Graduate/professional degree | 19 (6.3) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Monthly incomea,d | .82** | .43** | .30** | −.07 | −.08 | |

| <$1,000 | 31 (10.3) | – | – | – | – | – |

| $1,000–$1,999 | 42 (13.9) | – | – | – | – | – |

| $2,000–$2,999 | 50 (16.6) | – | – | – | – | – |

| $3,000–$3,999 | 52 (17.2) | – | – | – | – | – |

| $4,000–$5,999 | 57 (18.9) | – | – | – | – | – |

| ≥$6,000 | 64 (21.2) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Languagea,b,e | 123(40.8) | .49** | – | – | – | – |

| Nativitya,b,f | 75 (24.9) | .33** | .56** | – | – | – |

| Norepinephrine (μg/g creatinine) | 6.0 (3.7) | −.08 | −.04 | −.060 | 0 | – |

| Epinephrine (μg/g creatinine) | 2.6 (2.4) | −.08 | −.02 | −.03 | .64** | – |

p<.05;

p<.01

N (%)

Point biserial correlation

Post-menopausal 0 = 1, pre-menopausal = 0

Spearman rank-order correlation

English language survey = 1, Spanish language = 0

Born in USA = 1, Mexico = 0

Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured via a composite score of income and education

Norepinephrine (NE)

Epinephrine

SES, Acculturation, NOREPI, and EPI

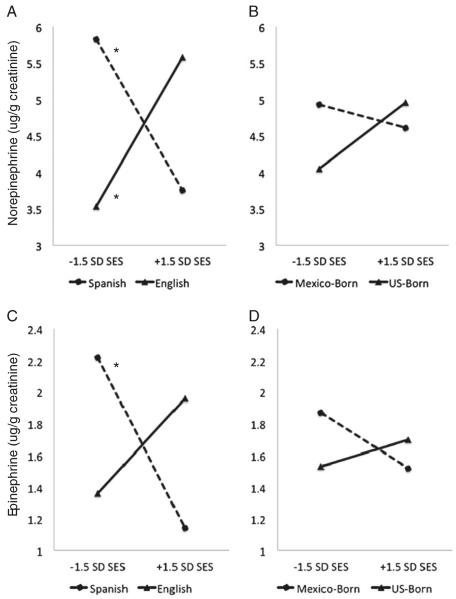

As shown in Table 2, there was no significant main effect of SES or either acculturation indicator in relation to NOREPI or EPI (ps>.10). However, a significant SES by language interaction effect was observed for both NOREPI (p<.01) and EPI (p<.05), in age-adjusted (model 1) and fully adjusted (model 2) models. A SES by nativity interaction approached significance for NOREPI (p=.05), and EPI (p<.10), in age-adjusted (model 1) models. In fully adjusted models, the SES by nativity interaction effect for NOREPI still approached significance (p=.05), and the interaction effect for EPI was nonsignificant (p>.10). As shown in Fig. 1, panels a and c, in lower acculturated women (Spanish speaking), higher SES showed the expected, inverse relationship with EPI and NOREPI (ps<.05). However, in higher acculturated women (English speaking), higher SES was associated with higher catecholamine levels, although this simple slope was statistically significant for NOREPI only (p<.05). Although the findings were nonsignificant, trends were similar for SES by nativity interaction effects (Fig. 1b, d).1

Table 2.

Results of hierarchical linear regression analyses regressing norepinephrine and epinephrine (log transformed) on socioeconomic status (SES), indicators of acculturation, and their interaction, adjusting for age (model 1) and biobehavioral covariates (model 2)

| Norepinephrine |

Epinephrine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

| B (SE) | Δ R 2 | B (SE) | Δ R 2 | B (SE) | Δ R 2 | B (SE) | Δ R 2 | |

| Covariates | 0.02* | 0.02 | 0.01+ | 0.03 | ||||

| SES | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.08) | ||||

| Language | −0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.00 | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.01 | 0.13 (0.15) | 0.01 |

| SES × language | 0.29 (0.09)** | 0.03** | 0.30 (0.10)** | 0.03** | 0.38 (0.15)* | 0.02* | 0.35 (0.16)* | 0.02* |

| SES | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.08 (0.07) | ||||

| Nativity | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.01 | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.02 | −0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 |

| SES × nativity | 0.10 (0.04)+ | 0.02+ | 0.09 (0.05)+ | 0.02+ | 0.14 (0.07)+ | 0.01+ | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.01 |

SES socioeconomic status; R2 change is presented for the addition of covariates, the combination of main effects, and interactions separately

p<0.10;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Fig. 1.

Interaction between socioeconomic status (SES) composite score and preferred language (a and c) and nativity (b and d) on urinary norepinephrine (upper figures) and epinephrine (lower figures). *p≤.05

Discussion

The current study found differences in the associations between SES and catecholamine levels by acculturation status in middle-aged Mexican-American women. Spanish-speaking Mexican-American women evidenced an inverse gradient similar to non-Hispanic white and African-American populations [5, 6], such that higher SES was related to lower catecholamine levels. However, in English-speaking Mexican-American women, SES was associated with higher catecholamine levels. Similar (but non-significant) patterns were observed for nativity. Notably, language preference may represent a better indicator of exposure to US culture than nativity in the San Diego–Mexico border region, where the border is a permeable boundary that is frequently crossed for social, educational, healthcare, commerce, or professional reasons.

The SES–health gradient may not operate consistently in Hispanic populations, and several studies have identified inconsistent, positive, flattened, or weakened gradients. For example, Goldman et al. [9] found that education gradients for obesity and smoking were relatively weak for adults of Mexican descent compared to those observed for non-Hispanic whites. Steffen [10] found a significant interaction between education and ethnicity in relation to ambulatory blood pressure. A positive relationship between education and blood pressure existed for Hispanics, whereas a negative relationship existed for non-Hispanic whites. However, the positive relationship was attenuated after adjustment for acculturation status. A large epidemiological study of women living in rural Mexico found that household income, housing, and assets were positively associated with systolic blood pressure [11]. However, when SES was measured using educational attainment, there was a negative association between SES and systolic blood pressure. The evidence to date reflects a complex landscape wherein the direction and magnitude of SES–health associations in Hispanics vary by health outcome, SES marker, and gender under study.

Given that psychological stress affects sympathetic nervous system activity [4], it is plausible that the differences by acculturation status observed in SES–catecholamine relationship are a result of exposure to unique stressors found within distinct cultural environments. Specifically, the positive associations between SES and catecholamines in English-speaking Mexican-American women may be explained, in part, by greater exposure to chronic stress [27, 28]. For example, more acculturated women of greater SES may feel increased pressure to balance social expectations and demands from both the Hispanic culture (which values more traditional gender roles; [29] and the US culture, such as the duality of balancing domestic tasks, marriage and children, with career demands. More generally, foreign-born and lower-acculturated Hispanics have been found to experience fewer life events and discrimination, when compared with US-born or more acculturated Hispanics [27, 28].

Although our study is novel, it should be interpreted in light of its limitations. The cross-sectional design prohibits conclusions regarding directionality of the observed associations. Acculturation was assessed by proxy markers, which have limited sensitivity and are unable to capture more complicated processes associated with health (e.g., bilingualism, changes in beliefs or behaviors). Approximately half of the sample was comprised of premenopausal women, but we did not collect data on menstrual phase, which is a potential confounder for the measurement of catecholamine levels [30]. Effect sizes, although significant, were not large. In addition, we did not impose an alpha level correction for multiple comparisons, and results should still be interpreted in light of the number of analyses. The study was intended to be an in-depth examination of middle-aged Mexican-American women living in communities with diverse SES near the San Diego–Mexico border region. Given the diversity of the Hispanic population, research on well-characterized, gender–ethnic–regional subgroups is needed in order to examine SES effects in health. However, the findings should not be presumed to generalize to other Hispanic populations.

The current study adds to the accumulating work on the interplay between SES, culture, and sympathetic nervous system activation in Hispanics. Moreover, our findings highlight the importance of considering the interactive effects of socioeconomic and cultural factors when studying Hispanic health. Even in our relatively homogenous sample, within-group differences emerged according to acculturation status, suggesting that culture is an important moderator of SES–health gradients. Specifically, the current findings suggest that both low SES, low-acculturated and high SES, high-acculturated Mexican-American women may be at elevated risk for cardiometabolic diseases, to the extent that elevated catecholamine levels are predictive of such outcomes [4, 31]. Whether or not these trends are observed within other Mexican-American female samples or other Hispanic gender-ethnic subgroups awaits further research.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by1R01HL081604 (NHLBI/NIH), and trainees were supported by 1T32HL079891-01A2 and F31HL087732 from the NHLBI/NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

1 We thank an anonymous reviewer for the suggestion of controlling for perceived stress as a potential confounder. Analyzing the data including a measure of overall perception of stress burden within the past 30 days [26] as a covariate did not substantively change results; consequently, for parsimony, these analyses are not presented.

References

- 1.Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:501–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller GE, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:501–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert E, Lambert G. Stress and its role in sympathetic nervous system activation in hypertension and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:244–248. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Baum A. Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:414–420. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221236.37158.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janicki-Deverts D, Cohen S, Adler NE, et al. Socioeconomic status is related to urinary catecholamines in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:514–520. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f60645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: Risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:712–722. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanagh A, Bentley RJ, Turrell G, et al. Socioeconomic position, gender, health behaviours and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman N, Kimbro RT, Turra CM, Pebley AR. Socioeconomic gradients in health for white and Mexican-origin populations. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2186–2193. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steffen P. The cultural gradient: Culture moderates the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and ambulatory blood pressure. J Behav Med. 2006;29:501–510. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernald LCH, Adler NE. Blood pressure and socioeconomic status in low-income women in Mexico: A reverse gradient? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:e8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosero-Bixby L, Dow WH. Surprising SES gradients in mortality, health, and biomarkers in a Latin American population of adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:105–17. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias E. United States life tables by Hispanic origin. Vital Health Stat 2. 2010;152:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talavera GA, LaVange L, Gallo LC, Perreira K, Penedo FJ, Daviglus M, et al. Prevalence of clinical CVD events in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Proceeding of the American Heart Association's Joint Conference—Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism / Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, Scientific Sessions; Atlanta, GA. March 22–24, 2011; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;13:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rojas R, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Jimenez-Corona A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in Mexican adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S11–18. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers. 2009;77:1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo LC, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Allison M, Diez-Roux AV, Polak JF, Morales LS. Do socioeconomic gradients in subclinical atherosclerosis vary according to acculturation level? Analyses of Mexican-Americans in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:756–62. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b0d2b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, Roesch SC, et al. Socioeconomic status, psychosocial resources and risk, and cardiometabolic risk in Mexican-American women. Health Psychol. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0025689. doi:10.1037/a0025689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian M, Morales L, Bautista D. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton WW. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESDR) Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan Oskamp., editor. The Social Psychology of Health. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tillman KH, Weiss UK. Nativity status and depressive symptoms among Hispanic young adults: The role of stress exposure. Soc Sci Q. 2009;90:1228–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Taylor J. Stress burden, drug dependence and the nativity paradox among U.S. Hispanics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kane EW. Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:419–439. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirshoren N, Tzoran I, Makrienko I, et al. Menstrual Cycle Effects on the Neurohumoral and Autonomi Nervous Systems Regulating the Cardiovascular System. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1569–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert GW, Straznicky NE, Lambert EA, Dixon JB, Schlaich MP. Sympathetic nervous activation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome—Causes, consequences and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:159–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]