Abstract

Sponge classification has long been based mainly on morphocladistic analyses but is now being greatly challenged by more than 12 years of accumulated analyses of molecular data analyses. The current study used phylogenetic hypotheses based on sequence data from 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and the CO1 barcoding fragment, combined with morphology to justify the resurrection of the order Axinellida Lévi, 1953. Axinellida occupies a key position in different morphologically derived topologies. The abandonment of Axinellida and the establishment of Halichondrida Vosmaer, 1887 sensu lato to contain Halichondriidae Gray, 1867, Axinellidae Carter, 1875, Bubaridae Topsent, 1894, Heteroxyidae Dendy, 1905, and a new family Dictyonellidae van Soest et al., 1990 was based on the conclusion that an axially condensed skeleton evolved independently in separate lineages in preference to the less parsimonious assumption that asters (star-shaped spicules), acanthostyles (club-shaped spicules with spines), and sigmata (C-shaped spicules) each evolved more than once. Our new molecular trees are congruent and contrast with the earlier, morphologically based, trees. The results show that axially condensed skeletons, asters, acanthostyles, and sigmata are all homoplasious characters. The unrecognized homoplasious nature of these characters explains much of the incongruence between molecular-based and morphology-based phylogenies. We use the molecular trees presented here as a basis for re-interpreting the morphological characters within Heteroscleromorpha. The implications for the classification of Heteroscleromorpha are discussed and a new order Biemnida ord. nov. is erected.

Introduction

There are approximately 8000 valid species of sponges, but this number is likely to be a gross underestimate given how poorly studied some faunas are, the cryptic nature of many of the habitats, and the occurrence of cryptic species (Cardenas et al. 2012). Of the 8000 described species, approximately 6650 belong to Demospongiae (Morrow et al. 2012). The currently accepted classification of sponges depends almost exclusively on the morphology of spicules and the arrangement of spicules within the sponge tissue. However, some of the most recent taxonomic studies have taken a more integrative approach using a combination of morphological and molecular characters (Cardenas et al. 2011) and also cytologic and metabolomic fingerprinting (Gazave et al. 2010a). Reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships within sponges is extremely challenging given the relative simplicity and environmental plasticity of the skeletal characters. This task is made more difficult by our lack of knowledge of whether specific skeletal characters indicate a common evolutionary origin (homologous) or whether they are a consequence of convergent evolution, parallel evolution, or evolutionary reversals (homoplasy). When the number of morphological characters available for analysis is high, the impact of undetected homoplasy may be small (Jenner 2004), but when there is a paucity of morphological characters, which is often the case with sponges, then the consequences of homoplasy can be significant for the classification. Compared with most other groups, the phylogenetic relationships among sponges are still largely unresolved, hindering attempts to achieve a stable classification for the group.

The Lévi-Bergquist-Hartman classification of Demospongiae

Lévi (1953, 1956, 1957, 1973) was the first to provide a modern synthesis of the classification of Demospongiae. He identified two subclasses; Tetractinomorpha for taxa with a radial or axially condensed skeleton and an oviparous mode of reproduction and Ceractinomorpha for taxa with a reticulate skeleton and viviparous reproduction. He erected a new order Axinellida, containing the family Axinellidae, which previously had been classified within Halichondrida (according to the classification of de Laubenfels, 1936). Hallmann (1917) and Lévi (1953, 1956) argued for the removal of Axinellidae from Halichondrida. Lévi (1953) suggested that Axinellida should be given ordinal status. He allocated the new order to the subclass Tetractinomorpha; this was largely based on reproductive strategies. Axinellida was interpreted as containing species that are oviparous and have an axially condensed skeleton whilst Halichondrida sensu stricto contained species that are viviparous with a confused or reticulate skeleton. Bergquist (1970), in her study of Axinellida and Halichondrida from New Zealand, concluded that the differences in life-cycle patterns between members of Axinellida and Halichondrida were sufficient to warrant their placement in separate orders. However, Bergquist (1967) pointed out that some axinellids (Raspailiidae Hentschel, 1923 and Sigmaxinellidae Lévi, 1955) have similar morphological features as some groups of Ceractinomorpha (i.e., Poecilosclerida Topsent, 1928) and are difficult to place between Poecilosclerida and Axinellida. In assigning them to Axinellida she placed emphasis on their reproductive strategies.

Both Bergquist (1970) and Hartman (1982) found support for Lévi’s classification, and this became known as the Lévi-Bergquist-Hartman system (L-B-H). Fig. 1A summarizes this classification and shows the families that were assigned to Axinellida.

Fig. 1.

(A) Summary of the Lévi–Bergquist–Hartman classification based primarily on skeletal architecture and reproductive strategies. (B) Summary of the Soest–Hooper classification based mainly on cladistic analyses of morphological characters. (C) Summary of the molecular results of this study based on full-length 18S rRNA combined with 28S rRNA (D3–D8 region) and CO1 barcoding sequences. Families assigned to Axinellida Lévi, 1953 are shown in bold. The distribution of asterose and sigmatose microscleres; axially condensed skeletons; acanthostyles and acanthoxea are shown on the three cladograms. Families currently assigned to Hadromerida in the World Porifera Database (van Soest et al. 2013) are indicated with an arrow (C).

The Soest–Hooper system

The first studies to utilize morphocladistics in sponge systematics were van Soest (1984a, 1987, 1990, 1991), van Soest et al. (1990), de Weerdt (1989), and Hooper (1990a, 1991). These studies were based primarily on skeletal characters. The results led to a new classification which was later adopted by Systema Porifera (Hooper and van Soest 2002) and which still underpins the current most widely used reference for sponge nomenclature, the World Porifera Database (van Soest et al. 2013). This classification differs from the L-B-H system primarily by the abandonment of Axinellida and the allocation of Axinellidae, Bubaridae, Heteroxyidae, and Dictyonellidae to Halichondrida; Hemiasterellidae Lendenfeld, 1889 and Trachycladidae Hallmann, 1917 to Hadromerida Topsent, 1894; and Raspailiidae (including Euryponidae Topsent, 1928), Rhabderemiidae Topsent, 1928, and Sigmaxinellidae to Poecilosclerida. This supports earlier findings that transferred the raspailiids to Poecilosclerida on the basis of shared acanthostyles and similar surface architecture in some species (Hooper 1990a).

Cladistic approaches to systematics were highly critical of the L-B-H system, in particular with regard to the changes Lévi proposed for Halichondrida and Poecilosclerida (van Soest 1987, 1991; van Soest et al. 1990). They argued that reproductive strategies cannot reasonably be interpreted as synapomorphies at the subclass level, and even at lower levels these can be an adaptive response, developed independently. These authors also pointed out that for many taxa reproductive strategies were unknown and were inferred from the skeletal arrangement, therebv making a circular argument. Typical members of Axinellidae, Raspailiidae, Hemiasterellidae, and Sigmaxinellidae share the possession of an axially condensed skeleton. van Soest et al. (1990) pointed out that each of these families also possessed characters that they interpreted as synapomorphies widely shared by different groups, such as asters in Hemiasterellidae with Hadromerida; acanthostyles in Raspailiidae with some Poecilosclerida; and sigmata in Sigmaxinellidae with other Poecilosclerida. van Soest et al. (1990) and van Soest (1991) proposed changes to the classification mainly based on the argument that it was more parsimonious to assume that an axially condensed skeleton had arisen independently in different lineages (Hadromerida, Halichondrida, and Poecilosclerida) than to assume that asters, acanthostyles, and sigmata each evolved independently in separate lineages. This classification, which became known as the Soest–Hooper system, is summarized in Fig. 1B.

The molecular classification

Early molecular phylogenetic studies of sponges used full-length sequences of 18S rRNA and the C1-D1 region of 28S rRNA and showed that the class Demospongiae is monophyletic, exclusive of Homoscleromorpha (Borchiellini et al. 2004). These results showed that Demospongiae consists of four well-supported clades: “G1” and “G2” subsequently named Keratosa and Myxospongiae and marine Haplosclerida (“G3”) and a large clade provisionally called G4. Subsequent molecular studies, e.g., Lavrov et al. (2008) using complete mitochondrial genomes, and Sperling et al. (2009, 2010) using nuclear housekeeping genes obtained largely congruent results. Sperling et al. (2009) proposed the name Democlavia for the G4 clade; however, Cardenas et al. (2012) later formally proposed Heteroscleromorpha for this clade. Heteroscleromorpha is by far the most important group of demosponges in terms of the number of taxa and contains approximately 5000 described species.

Within Heteroscleromorpha there is a large degree of incongruence between phylogenies reconstructed on the basis of molecular sequences and those based on cladistic analysis of morphological characters, as highlighted by Morrow et al. (2012). In the current study we attempted to gain an understanding of the causes of the incongruences by mapping the distribution of asterose and sigmatose microscleres, acanthostyles, and axially condensed skeletons onto updated molecular trees to gain an insight into whether these characters represent homologies or homoplasies (Fig. 1C).

Materials and methods

Samples and specimens

A combination of freshly collected specimens and museum specimens was used together with a number of sequences from Genbank. In total 154 species were included in this study; Table 1 shows the markers obtained and the corresponding catalogue numbers and Genbank accession numbers for each of the species. Most of the fresh material was collected by SCUBA diving, shore collecting, and by the ROV Holland I launched from RV Celtic Explorer. The sponges were photographed in situ prior to collection and samples no bigger than 1 cm3 were collected and fixed in 95% ethanol. When necessary the ethanol was changed after 20 min to fully desiccate the specimen.

Table 1.

A list of species used in this study arranged alphabetically with collecting localities

| Organism | Voucher | Locality | COX1 | 28S (D3–5) | 28S (D6–8) | 18S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthella acuta | Mc7160 | Mediterranean | HQ379408 | HQ379259 | HQ379331 | — |

| Acanthella acuta | — | Mediterranean | — | — | GQ466052 | |

| Acanthella cavernosa | Guam | — | KC869543 | — | ||

| Acanthella cavernosa | 0CDN9790-Z | Palau | — | — | KC902194 | |

| Acantheurypon pilosella | Mc7748 | Ireland | — | KC952007 | KC883679 | KC902379 |

| Acanthostylotella cornuta | 0CDN8730-X | Guam | — | KC869600 | KC902123 | |

| Adreus fascicularis | Mc4559 | English Channel | HQ379428 | HQ379314 | HQ379379 | KC902329 |

| Adreus sp. | Mc4982 | Ireland | — | HQ379311 | HQ379377 | KC902410 |

| Agelas axifera | G320422 | Australia | DQ069299 | — | — | |

| Agelas conifera | KC869634 | Panama | — | KC869634 | — | |

| Agelas conifera | — | — | — | — | AY734443 | |

| Agelas dispar | NCI171 | USA | — | KC884836 | — | |

| Agelas dispar | — | — | DQ075710 | — | AY737640 | |

| Amorphinopsis excavans | 0CDN9237-Y | Malaysia | — | KC869473 | KC902330 | |

| Amphilectus fucorum | Mc5093 | Wales | — | HQ379294 | HQ379362 | KC902221 |

| Ancorina alata | 0CDN6664-C | New Zealand | — | KC884835 | KC901881 | |

| Ancorina alata | 0CDN6551-G | New Zealand | — | KC884845 | KC902129 | |

| Anomomycale titubans | Mc7765 | Ireland | — | HQ379297 | HQ379365 | KC902230 |

| Antho involvens | Mc4262 | Scotland | — | HQ379291 | HQ379359 | KC902050 |

| Astrosclera willeyana | 0CDN5435-R | Tonga | — | KC869525 | KC902051 | |

| Atergia corticata | Mc7715 | Ireland | — | KC883681 | KC883680 | KC902079 |

| Axechina raspailioides | 0M9H2473-G | Australia | — | KC869448 | KC902059 | |

| Axinella infundifuliformis | Mc4438 | Scotland | HQ379410 | — | — | |

| Axinella polypoides | — | Mediterranean | — | DQ299255 | APU43190 | |

| Axinella pyramidata | Mc3385 | Ireland | — | HQ379265 | HQ379335 | KC902269 |

| Axinella vaceleti | Mc4200 | Mediterranean | — | HQ379266 | HQ379336 | KC902004 |

| Axinyssa topsenti | 0CDN8822-X | Papua New Guinea | — | KC869558 | KC902315 | |

| Biemna saucia | G303281 | Australia | JF773146 | — | — | |

| Biemna variantia | Mc5405 | Wales | HQ379424 | HQ379292 | HQ379360 | KC901961 |

| Ceratopsion axiferum | 0M9H2585-A | Australia | — | KC869596 | KC902000 | |

| Cervicornia cuspidifera | 0M9G1351-I | USA | — | KC869474 | KC902382 | |

| Cinachyrella kuekenthali | P23 | Panama | KC869490 | — | ||

| Cinachyrella kuekenthali | — | — | EF519602 | — | — | |

| Cinachyrella kuekenthali | USNM_1133786 | Panama | — | — | KC902290 | |

| Ciocalypta penicillus | Mc5051 | Roscoff/France | — | HQ379315 | HQ379381 | KC902049 |

| Clathria armata | Mc4359 | Scotland | KC869418 | KC869437 | KC869445 | KC901940 |

| Clathria barleei | Mc4347 | Scotland | KC883682 | HQ393897 | HQ393901 | KC902394 |

| Clathria oxeota | B66 | Belize | EF519605 | — | — | |

| Clathria rugosa | G300696 | New Caledonia | HE611604 | — | — | |

| Clathria schoenus | P10 | Panama | — | KC884834 | — | |

| Clathria schoenus | SI06x33 | Panama | — | — | KC902370 | |

| Cliona celata | Mc5497 | Wales | HQ379310 | HQ379376 | KC902383 | |

| Cliona celata | EF519608 | |||||

| Cliona varians | 0M9G1439-C | USA | — | KC869519 | KC902145 | |

| Crella elegans | Mc7174 | Mediterranean | KC876698 | HQ393898 | HQ393902 | KC902282 |

| Crella rosea | Mc2418 | Ireland | — | HQ379299 | HQ379367 | KC902058 |

| Cymbaxinella corrugata | USNM_1133767 | Panama | — | KC869523 | KC902298 | |

| Cymbaxinella damicornis | Mc4987 | Ireland | — | HQ379261 | HQ379333 | KC902335 |

| Desmacella cf. annexa | Mc4240a | Scotland | KC876697 | HQ379293 | HQ379361 | KC902284 |

| Desmoxya pelagiae | Mc7764 | Ireland | KC876696 | — | — | |

| Dictyonella sp. | NCI228 | Australia | — | KC884834 | — | |

| Dictyonella incisa | Mc2041 | Mediterranean | — | — | KC902014 | |

| Dragmacidon reticulatum | — | — | AJ843894 | — | — | |

| Dysidea arenaria | — | Vanuatu | JQ082809 | — | — | |

| Ecionemia acervus | 0CDN7076-Z | Palau | — | KC884842 | KC902119 | |

| Ectyoplasia ferox | USNM_1133718 | Panama | EF519612 | KC869540 | KC901974 | |

| Ectyoplasia ferox | — | Caribbean | EF519612 | — | — | |

| Ectyoplasia tabula | 0M9H2632-C | Australia | — | KC869472 | KC901950 | |

| Endectyon delaubenfelsi | Mc4527 | English Channel | HQ379412 | — | — | |

| Ephydatia cooperensis | — | — | DQ087505 | — | — | |

| Eurypon clavigerum | Mc4992 | Ireland | — | HQ379272 | HQ379340 | KC901988 |

| Eurypon hispidum | 0CDN7586-G | Vanuatu | — | KC869614 | KC902068 | |

| Forcepia sp. | 0CDN7230-S | S. Africa | — | KC869627 | KC902407 | |

| Geodia vestigifera | 0CDN6732-A | New Zealand | — | KC884832 | KC901913 | |

| Halichondria bowerbanki | Mc4003 | Ireland | — | HQ379316 | HQ379382 | KC902247 |

| Halichondria melanadocia | USNM_1133755 | Panama | — | KC869508 | KC902080 | |

| Halichondria panicea | Mc4070 | Ireland | KC869423 | HQ379317 | HQ379383 | KC902238 |

| Halicnemia sp. | Mc5427 | Ireland | HQ379422 | HQ379287 | HQ379355 | KC902045 |

| Halicnemia verticillata | Mc5018 | Ireland | HQ379414 | — | — | |

| Higginsia anfractuosa | 0CDN3725-J | Tanzania | — | KC884840 | KC902091 | |

| Higginsia mixta | Malaysia | — | KC869485 | — | ||

| Higginsia mixta | 0CDN9379-F | Malaysia | — | — | KC902154 | |

| Higginsia petrosioides | G300611 | Australia | JQ034564 | — | — | |

| Homaxinella subdola | Mc5438 | Wales | — | HQ379318 | HQ379385 | KC901944 |

| Hymedesmia pansa | Mc5725 | Wales | — | HQ379301 | HQ379368 | KC902027 |

| Hymeniacidon heliophila | 0M9G1074-H | USA | — | KC884838 | KC901957 | |

| Hymeniacidon kitchingi | Mc3332 | Ireland | — | KC869434 | HQ379384 | KC902333 |

| Hymeraphia breeni | Mc4693 | Ireland | KC869421 | — | — | |

| Hymeraphia stellifera | Mc4669 | Ireland | — | HQ379275 | HQ379343 | KC901948 |

| Hymerhabdia typica | Mc4588 | Ireland | KC869425 | HQ379289 | HQ379357 | KC902371 |

| Jaspis novaezelandiae | 0CDN6804-G | New Zealand | — | KC895549 | KC901966 | |

| Lamellodysidea herbacea | 0PHG1160-T | Malaysia | — | KC869535 | KC902214 | |

| Latrunculia lunavirdis | 0CDN7382-J | S. Africa | — | KC869489 | KC902327 | |

| Lissodendoryx arenaria | 0CDN7285-C | S. Africa | — | KC869561 | KC901932 | |

| Lissodendoryx colombiensis | USNM_1133712 | Panama | — | KC869647 | KC902105 | |

| Lissodendoryx fibrosa | 0CDN9368-R | Malaysia | — | KC869479 | KC901973 | |

| Lissodendoryx jenjonesae | Mc4281 | Scotland | — | HQ379298 | HQ379366 | KC902088 |

| Lissodendoryx sp. | 0M9I5828-T | Malaysia | — | KC869506 | KC902216 | |

| Microciona prolifera | — | — | DQ087475 | — | — | |

| Microscleroderma herdmanni | 0CDN9628-Y | Palau | — | KC884846 | KC902255 | |

| Monanchora arbuscula | SI06x186 | Panama | — | KC869447 | KC902187 | |

| Mycale macilenta | Mc3618 | Ireland | — | KC869436 | KC869442 | KC901898 |

| Mycale mirabilis | 0PHG1422-F | Malaysia | HE611591 | KC869613 | KC902146 | |

| Mycale rotalis | Mc5391 | Wales | — | HQ379296 | HQ379364 | KC902397 |

| Mycale subclavata | Mc3314 | Ireland | — | KC869433 | KC869441 | KC902072 |

| Myrmekioderma granulatum | 0PHG1422-F | Malaysia | — | KC869471 | KC901877 | |

| Myrmekioderma gyroderma | — | — | EF519652 | — | — | |

| Myxilla anchorata | Mc3306 | Ireland | — | HQ379304 | HQ379370 | — |

| Myxilla anchorata | Mc4255 | Scotland | — | — | KC902360 | |

| Myxilla cf. rosacea | Mc4681 | Ireland | — | KC883686 | KC883683 | KC901935 |

| Neofibularia hartmani | 0CDN8100-O | Samoa | JF773145 | KC869639 | KC901997 | |

| Neofibularia nolitangere | — | — | EF519653 | — | — | |

| Pachymatisma johnstoni | Mc3504 | Scotland | EF564330 | — | — | |

| Paratimea cf. duplex | PS70/17-1(1) | Norway | KC869429 | — | — | |

| Paratimea sp. | Mc4323 | Scotland | HQ379419 | HQ379284 | HQ379352 | HQ379419 |

| Paratimea sp. | Mc5226 | Wales | — | HQ379283 | HQ379351 | KC902401 |

| Penares cf. alata | 0CDN7316-M | S. Africa | — | KC869466 | KC902193 | |

| Phakellia rugosa | Mc7456 | Norway | KC869419 | — | — | |

| Phakellia ventilabrum | Mc4248 | Scotland | HQ379409 | HQ379260 | HQ379332 | KC901915 |

| Phorbas bihamiger | Mc4493 | English Channel | — | KC869431 | KC869444 | KC901921 |

| Phorbas dives | Mc4517 | English Channel | — | HQ379303 | HQ379369 | KC902286 |

| Phorbas punctatus | Mc5343 | Wales | — | KC869439 | KC869440 | KC902093 |

| Pione vastifica | — | Caribbean | EF519665 | — | — | |

| Placospongia intermedia | PC-BT-18 | Panama | KC869430 | — | — | |

| Plocamionida ambigua | Mc4345 | Scotland | — | KC869435 | KC869443 | KC902218 |

| Polymastia boletiformis | Mc5014 | Ireland | — | HQ379306 | HQ379372 | KC902065 |

| Polymastia janeirensis | — | Brazil | EU076813 | — | — | |

| Polymastia penicillus | Mc5284 | Ireland | — | HQ393899 | HQ393903 | — |

| Polymastia penicillus | Mc5065 | Ireland | — | — | KC902065 | |

| Polymastia sp. | Mc6488 | Ireland | KC869420 | — | — | |

| Prosuberites longispinus | Mc7173 | Mediterranean | — | HQ379320 | HQ379387 | KC902182 |

| Ptilocaulis spiculifer | 0CDN9412-P | Malaysia | — | KC869560 | KC902092 | |

| Ptilocaulis walpersi | — | Bahamas | EU237488 | — | — | |

| Raspaciona aculeata | Mc7159 | Mediterranean | HQ379415 | — | — | |

| Raspailia hispida | Mc3597 | Ireland | HQ379416 | HQ379279 | HQ379348 | KC902385 |

| Raspailia phakellopsis | 0M9H2417-T | Australia | — | KC869585 | KC902272 | |

| Raspailia ramosa | Mc4024 | Ireland | HQ379417 | HQ379281 | HQ379349 | KC902299 |

| Raspailia vestigifera | NCI431 | Australia | — | KC869583 | KC901895 | |

| Reniochalina stalagmitis | NCI287 | Australia | — | KC869582 | — | |

| Reniochalina stalagmitis | — | — | — | EF092272 | ||

| Rhabdastrella globostellata | 0PHG1710-R | Vietnam | — | KC884843 | KC902160 | |

| Rhabderemia sorokinae | G312904 | Papua New Guinea | HE611607 | — | — | |

| Scopalina hispida | NCI272 | USA | — | KC884841 | KC902237 | |

| Scopalina lophyropoda | Mc4217 | Mediterranean | — | HQ379268 | HQ379337 | KC901894 |

| Scopalina ruetzleri | Panama | — | KC869553 | — | ||

| Scopalina ruetzleri | — | — | — | — | AJ621546 | |

| Spanioplon armaturum | Mc4500 | English Channel | EF519602 | KC869438 | KC869446 | KC902324 |

| Sphaerotylus antarcticus | POR21125 | Antarctica | KC869424 | — | — | |

| Sphaerotylus sp. C | Mc4236 | Ireland | — | HQ379307 | HQ379373 | — |

| Sphaerotylus sp. C | Mc4697 | Ireland | — | — | KC902307 | |

| Spongilla lacustris | Mc7351 | Ireland | HQ379431 | HQ379327 | HQ379393 | KC902349 |

| Stelletta clavosa | 0CDN9840-G | Palau | — | KC884847 | KC901967 | |

| Stelletta grubii | Mc5043 | Ireland | — | HQ379255 | HQ379329 | KC902213 |

| Stelligera rigida | Mc4357 | Scotland | HQ379420 | HQ379285 | HQ379353 | KC902164 |

| Stelligera stuposa | Mc4330 | Scotland | HQ379421 | HQ379286 | HQ379354 | KC902232 |

| Stryphnus ponderosus | Mc4240 | Scotland | — | HQ379257 | HQ379330 | — |

| Suberites aurantiacus | KC869577 | Panama | — | KC869577 | — | |

| Suberites aurantiacus | SI06x105 | Panama | — | — | KC902366 | |

| Suberites ficus | Mc4322 | Ireland | HQ379429 | HQ379322 | HQ379389 | KC902236 |

| Suberites massa | Mc4528 | English Channel | — | HQ379324 | HQ379390 | KC902066 |

| Suberites pagurorum | Mc4043 | Ireland | KC869422 | — | — | |

| Svenzea zeai | USNM_1133762 | Panama | — | KC869635 | KC902075 | |

| Tedania strongylostyla | 0CDN7611-I | Vanuatu | — | KC869515 | KC901911 | |

| Terpios aploos | 0CDN3602-Y | Tanzania | — | KC869465 | KC902316 | |

| Terpios gelatinosa | Mc3315 | Ireland | — | HQ379325 | HQ379391 | KC902355 |

| Tethya actinea | SI06x109 | Panama | — | KC869527 | — | |

| Tethya actinea | — | — | — | — | AY878079 | |

| Tethya aurantium | — | Mediterranean | EF584565 | — | — | |

| Tethya citrina | Mc5113 | Wales | HQ379427 | — | — | |

| Tethya norvegica | — | Norway | EF558565 | — | — | |

| Tethyopsis mortenseni | 0CDN6706-X | New Zealand | — | KC869618 | KC902095 | |

| Tethyopsis sp. | 0CDN6825-C | New Zealand | — | KC869476 | KC902234 | |

| Tethyspira spinosa | Mc4641 | Ireland | HQ379418 | HQ379282 | HQ379350 | KC902120 |

| Theonella cylindrica | 0CDN9523-L | Malaysia | — | KC884839 | KC902244 | |

| Theonella swinhoei | 0CDN9465-W | Malaysia | — | KC884844 | KC901886 | |

| Timea unistellata | Mc7300 | Ireland | KC869427 | — | — | |

| Topsentia sp. | P126 | Panama | — | KC884837 | — | |

| Topsentia sp. | 0CDN8723-Q | Guam | — | — | KC902261 | |

| Trachycladus stylifer | 0CDN6656-T | New Zealand | — | KC869453 | KC901930 | |

| Trachytedania cf. ferrolensis | Mc5348 | Wales | — | KC883684 | KC883685 | KC902219 |

| Tsitsikamma pedunculata | 0CDN7414-S | S. Africa | — | KC869512 | KC902279 | |

| Ulosa stuposa | Mc4523 | English Channel | KC869428 | HQ379295 | HQ379363 | KC901912 |

Catalogue numbers for the voucher specimens are from the Ulster Museum Belfast, Porifera Collection (Mc-); National Cancer Institute (NCI) collection, maintained by the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) The Queensland Museum, Porifera Collection (G) and a variety of specimens collated by the Porifera Tree of Life project. PC-BT-18 and PS70/70/17-(1) are from Paco Cardenas' private collection. The 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and CO1 sequences used in this study are shown with their GenBank accession numbers.

DNA extraction

At Queen’s University Belfast, DNA was extracted from subsamples following the methods outlined by Morrow et al. (2012). At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, DNA was extracted from subsamples following the procedures outlined by Thacker et al. (2013, this issue). Details of DNA extraction at the National Museum of Natural History are given by Redmond et al. (2013, this issue).

PCR amplification

18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and CO1 barcoding region were chosen for amplification as these genes have been shown to be useful phylogenetic markers in sponges (Erpenbeck et al. 2007; Wörheide et al. 2007; Cárdenas, 2010; Gazave et al. 2010b). Details of PCR protocols and primers used for amplifying and sequencing are given by Morrow et al. (2012) for 28S rRNA and CO1 sequences, Thacker et al. (2013, this issue) for additional 28S sequences and Redmond et al. (2013, this issue) for 18S sequences.

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequences were managed in Geneious Pro 4.7 software (Drummond et al. 2009). Forward and reverse reads were assembled into contigs using the assembly function of the software and checked for inconsistencies. In cases in which the forward and reverse reads disagreed, Geneious automatically used the better quality of the two reads or introduced an IUPAC ambiguity code into the consensus sequence. The sequences were aligned with MUSCLE v. 3.6 (Edgar 2004a, 2004b) and trimmed in Geneious. Question marks were used for any missing data. JModelTest (Darriba et al. 2012) identified the GTR + G + I model as the best-fit model of molecular evolution for all datasets.

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood in RaxML (Stamatakis et al. 2008) and Bayesian inference in MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). The best tree from RaxML is illustrated showing bootstrap supports >50 and posterior probabilities >0.5 from the Bayesian analysis. Additional partitioned analyses and analyses treating saturation of the third codon in the CO1 barcoding sequences with RY coding gave the same topology.

Whilst previous molecular studies have suggested that Haploscleromorpha (= marine haplosclerids) are the sister group to Heteroscleromorpha (Borchiellini et al. 2004; Lavrov et al. 2008), Erpenbeck et al. (2004) demonstrated that ribosomal sequences in Haploscleromorpha showed increased evolutionary substitution rates, which disqualifies them as a suitable outgroup taxa for rRNA analyses of Heteroscleromorpha; therefore Lamellodysidea herbacea (Keller, 1889) and Dysidea arenaria Bergquist, 1965 (Keratosa: Demospongiae) were chosen for the combined 18S-28S rRNA analysis and the combined 18S-28S-CO1 analysis, respectively. For consistency Dysidea arenaria was chosen as the outgroup for our CO1 analysis.

Results

Description of the trees

A genetree based on RaxML analysis of combined full-length 18S and 28S (D3–D8 region) rRNA sequences of 121 species was constructed using a wide range of species both from this work and from previous studies (Fig. 2). While it was not always possible to represent the same species, a second tree (Fig. 3), based on mitochondrial CO1 barcoding sequences from 57 taxa, covering the same genera as the 18S-28S tree, was constructed using RaxML. The CO1 tree recovered the same clades as the 18S-28S genetree but had a different branching order and less resolution. A genetree based on RaxML analysis of combined 18S, 28S rRNA and CO1 sequences of 33 taxa was constructed (Fig. 4). In order to have representatives of Axinellidae and Polymastiidae Gray, 1867, the 18S and 28S rRNA sequences of Axinella vaceleti Pansini, 1984 were concatenated with the CO1 sequences of Axinella infundibuliformis (Linnaeus, 1759) and the 18S and 28S rRNA sequences of Polymastia penicillus (Montagu, 1818) were concatenated with Polymastia sp. A separate analysis of CO1 sequences (Fig. 3) shows A. infundibuliformis grouping within Axinellidae and Polymastia sp. within Polymastiidae.

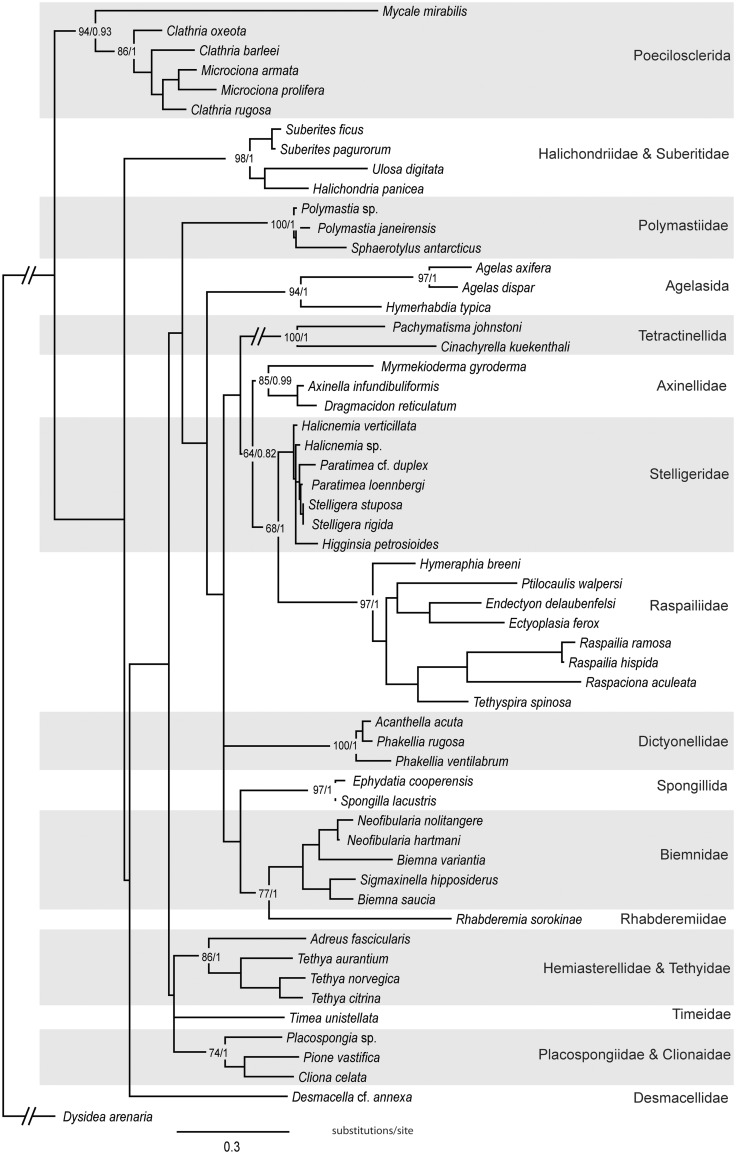

Fig. 2.

Best tree output from RaxML analysis of full-length 18S rRNA combined with 28S rRNA (D3–D8 region) sequences from 121 species of demosponges. Figures at nodes correspond to bootstrap support >50 followed by posterior probabilities >0.5 from the Bayesian analysis.

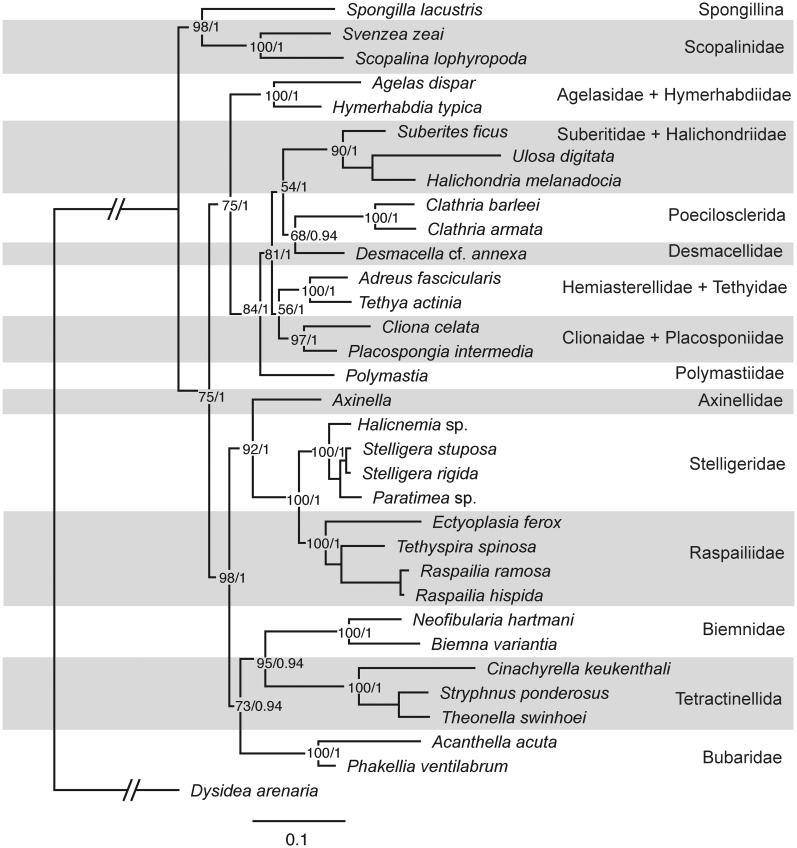

Fig. 3.

Best tree output from RaxML analysis of mitochondrial CO1 barcoding fragment from 57 species of demosponges. Figures at nodes correspond to bootstrap support >50 followed by posterior probabilities >0.5 from the Bayesian analysis.

Fig. 4.

Best tree output from RaxML combined analysis of full-length 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA (D3–D8 region) and mitochondrial CO1 barcoding fragment from 33 species of demosponges. Figures at nodes correspond to bootstrap support >50 followed by posterior probabilities >0.5 from the Bayesian analysis.

The resulting genetrees (Figs. 2–4) are congruent with the 28S rRNA and CO1 genetrees of Morrow et al. (2012). However, our combined trees (Figs. 2 and 4) have better resolution, particularly of the deeper nodes, and stronger support values. Gazave et al. (2010b) combined full-length 18S rRNA sequences with the C1-D3 region of 28S rRNA; their resulting dataset had 29 species and 2623 positions. Our combined 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA (D3–D8 region) analysis (Fig. 2) is substantially larger and contains 121 species and 3217 positions. This is the first study to do a combined analysis of 18S, 28S, and CO1 sequences for demosponges. Our combined dataset had 33 taxa and the alignment had 3811 positions. Our results conflict with many of the orders, families, and genera of the (morphological) classification of Systema Porifera (Hooper and van Soest 2002).

Our results are congruent with previous molecular studies using ribosomal and mitochondrial markers (e.g., Erpenbeck et al. 2007a, 2007b; Nichols 2005) but contrast with the recent results of Hill et al. (2013) which attempted to reconstruct family-level relationships within Demospongiae using seven nuclear housekeeping genes. One of the major differences concerned the relative position of Spongillida (freshwater sponges). In our analyses Spongillida clustered with Scopalinidae and was sister to the main heteroscleromorph clade. However, in Hill et al. (2013) Spongillida did not group with Heteroscleromorpha but was sister to Haploscleromorpha. In that analysis Tetractinellida was the sister group to the main heteroscleromorph clade but with very low support values. It is difficult to compare our phylogeny with that of Hill et al. which had very low taxon sampling (several of the families we included were not sampled and most of the families were only represented by one taxon) and low support for many of the deeper nodes. Graybeal (1998) and Wiens (1988) demonstrated that increased taxon sampling rather than increased number of characters is more effective in resolving difficult phylogenetic problems.

The 14 clades that are highlighted and named in Figs. 2 and 4 are also those recovered by Morrow et al. (2012). The combined analyses (Figs. 2 and 4) show strong support for a large clade encompassing Axinellidae s.s., Raspailiidae, and Stelligeridae Lendenfeld, 1898. Although Morrow et al. (2012) did not resolve the position of Tetractinellida, Bubaridae (Dictyonellidae), and Biemnidae relative to the rest of the heteroscleromorph clades, our combined analysis in Fig. 4 shows strong support for Biemnidae being the sister group to Tetractinellida with Bubaridae as the sister group to these two clades.

The CO1 genetree (Fig. 3) also supports the clades highlighted in Figs. 2 and 4; however, Scopalinidae was not represented. The CO1 genetree supports a clade with Axinellidae s.s., Raspailiidae, and Stelligeridae; however, the support is much lower than with ribosomal genes (Fig. 2). Erpenbeck et al. (2006, 2007b) pointed out that the CO1 barcoding region did not have sufficient phylogenetic signal to resolve the relationships between clades. Therefore the 18S + 28S tree is our preferred tree for inferring phylogenetic relationships among clades and improving systematics of the group.

Discussion

The division of Demospongiae into two subclasses, Tetractinomorpha (oviparous) and Ceractinomorpha (ovoviviparous), by Lévi (1956) based on reproductive strategies has now been abandoned as several congruent molecular studies have not supported this division (Lafay et al. 1992; Borchiellini et al. 2004; Nichols 2005). Mode of reproduction appears to be a homoplasious character (van Soest et al. 1990; Cardenas et al. 2012). It is possible to reconcile the characters used by traditional taxonomists with our molecular results if we reinterpret the spicule characters used and accept significant levels of homoplasy and character loss. Below we discuss the distribution of asterose and sigmatose microscleres, acanthostyles, and axially condensed skeletons within Heteroscleromorpha. One of the major problems with using cladistics in sponge taxonomy is that often the name given to a type of spicule is descriptive only and does not imply homology (Boury-Esnault 2006). These new results help to illuminate the evolutionary plasticity of heteroscleromorph skeletal elements.

Sigmata

The term sigma is used for C- or S-shaped microscleres. The Soest-Hooper system placed Haploscleromorpha (= marine haplosclerids) as sister group to Poecilosclerida, primarily on the basis that sigmatose microscleres are found in both (Fig. 1B). Subsequent molecular studies using 18S and 28S rRNA (Borchiellini et al. 2004), 28S rRNA and CO1 (Nichols 2005), 28S rRNA (Holmes and Blanch 2007), complete mitochondrial genomes (Lavrov et al. 2008), and housekeeping genes (Sperling et al. 2009; Hill et al. 2013) are congruent and show Haploscleromorpha as sister to Heteroscleromorpha. Fromont and Bergquist (1990) studied the different types of sigma found in Haploscleromorpha and Poecilosclerida and concluded that attempts to classify sponges on the basis of general morphological characters such as sigmata was an oversimplification of their diversity and resulted in misleading results. Sigmatose microscleres are found in Biemnidae Hentschel, 1923, Desmacellidae Ridley and Dendy, 1886, Poecilosclerida and Haploscleromorpha; this indicates that the presence of sigmata can be homoplasious (Fig. 1C).

Our CO1 genetree (Fig. 3) shows Rhabderemia sorokinae Hooper, 1990 clustering with Biemna spp., Neofibularia spp., and Sigmaxinella. On the basis of skeletal characters (mainly the shared possession of sigmata), Hooper (1984) synonymized Sigmaxinellidae (Axinellida) and Biemnidae (Poecilosclerida) into a single family Desmacellidae and assigned Desmacellidae to Axinellida. Lévi (1955) gave a diagnosis of Sigmaxinellidae as “axinellids with sigmoid microscleres;” however, he commented that the status of this family was very uncertain as the spicules might be analogous with those in Biemnidae. van Soest (1984b) transferred Desmacellidae to Poecilosclerida.

Rhabderemiidae

Hooper (1990b) synonymized Rhabdosigma Hallmann, 1916 with Rhabderemia Topsent, 1890 and transferred Rhabderemiidae from Axinellida to Microcionina Hajdu et al., 1994: Poecilosclerida on the basis that the monactinal megascleres and the structure of the microscleres are homologous with those of poecilosclerids. Rhabderemiidae is a monogeneric family with rhabdostyle megascleres; microscleres (if present) include rugose oxeote or toxa-like spicules (thraustoxeas), rugose sigma-like spicules (spirosigmata, thraustosigmata), and rugose microstyles (Hooper 2002). van Soest and Hooper (1993) indicated that there is some doubt over the homology of the sigmoid toxiform microscleres between Rhabderemiidae and other poecilosclerids. Rhabderemia sorokinae clusters with Biemna spp., Neofibularia spp., and Sigmaxinella hipposiderus Mitchell et al., 2011 and not with microcionid taxa in Poecilosclerida (Fig. 3).

There is also morphological support for Rhabderemiidae having a close relationship with Biemnidae/Sigmaxinellidae. Cedro et al. (forthcoming) described a new species of Rhabderemia that has sigmata with microspined ends, similar to the sigma in some Biemna species. e.g., B. microacanthosigmata Mothes et al., 2004 and Sigmaxinella cearense Salani et al., 2006. Biemna rhabderemioides Bergquist, 1961 and Biemna rhabdostyla Uriz, 1988 have rhabdose megascleres that resemble those found in Rhabderemia. van Soest and Hooper (1993) assumed that the rhabdostyles found in Rhabderemia and Biemna were homoplasious and did not indicate a close phylogenetic relationship between the two genera. However, in B. rhabdostyla, Uriz (1988) highlighted the fact that this species has “normal” Biemna spicules, i.e., “normal” styles, sigmata, raphides, and microxea, but in addition it also has rhabdostyles whilst B. rhabderemioides has only rhabdose styles. These two species are intermediate between Biemna and Rhabderemia and lend morphological support to the hypothesis that the two families are closely related.

The ribosomal genetree shows Biemnidae as sister group to Tetractinellida Marshall, 1876; this relationship was strongly supported by our Bayesian analysis (p.p.1) but had relatively weak support using RaxML (62 b.s.). The sigmaspires and raphides present in Spirophorina Bergquist and Hogg, 1969 (Tetractinellida) are possibly synapomorphic with the sigmaspires found in Rhabderemia and the raphides in Biemna and Neofibularia. The sigmaspires in Rhabderemia are similar to those found in Spirophorina. They are C-shaped or S-shaped, sometimes with a double twist, and the surface is minutely hispid; they also have similar dimensions. The tentative relationship suggested here needs to be tested with other markers, other Rhabderemia species, and a more detailed comparison of morphological characters.

Asters

Fig. 1C shows the distribution of asterose microscleres (star-shaped spicules) on our molecular tree. The families Hemiasterellidae and Trachycladidae were included in Axinellida Lévi, 1953. van Soest et al. (1990) assigned them to Hadromerida on the basis of the shared possession of asters. Several molecular studies have now demonstrated that asters are homoplasious (Chombard et al. 1998; Borchiellini et al. 2004; Nichols 2005; Morrow et al. 2012). Asterose microscleres have arisen independently on at least four occasions (Fig. 1C): in Myxospongiae Haeckel, 1866 (Chondrillidae Gray, 1872); Tetractinellida (Astrophorina Sollas, 1888); Axinellida (Stelligeridae), and Hadromerida (Hemiasterellidae, Tethyidae Gray, 1848, Trachycladidae, Timeidae Topsent, 1928). Asterose spicules are mainly found in the surface ectosomal layer of sponges. In the phylum Tunicata, calcium carbonate asterose spicules are also found in the surface layer of Didemnidae Giard, 1872 (Kott 2004). The presence of asterose spicules is likely to be a functional response that leads to a strengthening of the surface layer. It is also possible that asters may play an additional role in deterring predators.

Our analyses show that Trachycladus stylifer Carter, 1879 clusters with members of Hemiasterellidae (Adreus spp.) but our results also show that Hemiasterellidae is polyphyletic (Fig. 2). Paratimea Hallmann, 1917 and Adreus Gray, 1867 both have euaster microscleres and are currently considered to belong to Hemiasterellidae (van Soest et al. 2013) yet they do not form a monophyletic assemblage (Fig. 2). Morrow et al. (2012) moved these genera into the family Stelligeridae. Re-examination of the asters in Paratimea and Stelligera Gray, 1867 shows that they are quite different to those found in Adreus and Tethya Lamarck, 1817. In Paratimea and Stelligera they are always smooth-rayed and there is only one size category, whereas in Adreus, Tethya, and Hemiasterella Carter, 1879 the asters often have microspined rays and come in a variety of size classes.

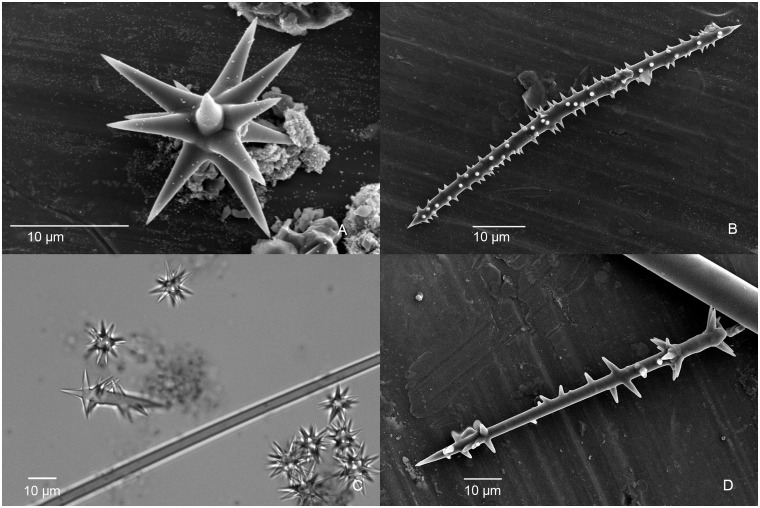

The molecular data presented here and in previous studies show that Stelligera and Paratimea have a close relationship with Halicnemia Bowerbank, 1864 and Higginsia Higgin, 1877 (Heteroxyidae), all of which have acanthose oxea (Erpenbeck et al. 2012; Morrow et al. 2012). Topsent (1897) considered the acanthoxea as derived from asters. It is possible that the asters in Stelligera/Paratimea are homologous at some level with the acanthoxea in Halicnemia/Higginsia, with the latter being an elongate derivative of the former. Fig. 5A shows a normal euaster in Paratimea sp.; Fig. 5B an acanthoxea in Halicnemia sp.; Fig. 5C an aberrant aster that is transitional between an aster and an acanthoxea; and Fig. 5D an acanthostyle from the raspailiid sponge Tethyspira spinosa Topsent, 1890. Similarly, the acanthostyles in Raspailiidae could also have been derived from asters. However, testing these speculations will require detailed examination of the formation and growth of the spicules.

Fig. 5.

(A) Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of euaster from Paratimea loennbergi (Mc1590); (B) SEM of acanthoxea from Halicnemia sp. (Mc1598); (C) Photomicrograph of an aberrant elongate aster from Paratimea sp. (Mc 3163); (D) SEM of acanthostyle from Tethyspira spinosa (Mc3163). Catalogue numbers refer to Ulster Museum (BELUM) Porifera collection.

Acanthostyles

Fig. 1C shows the distribution of acanthostyles within Heteroscleromorpha. Acanthostyles are found in Poecilosclerida s.s. (Microcionina; Myxillina Hajdu et al., 1994), Agelasida Hartman, 1980, and Raspailiidae. From their distribution on our tree it seems likely that acanthostyles are homoplasious. Within Agelasida the acanthostyles usually have spines arranged in whorls (verticilles) although in Acanthostylotella Burton and Rao, 1932 the spines are not obviously verticillate. van Soest (1991) considered asters to be confined to the group Astrophorida-Hadromerida-Hemiasterellidae (Fig. 1B) and regarded asters as a synapomorphy for a clade composed of these three groups. In his resulting classification, acanthostyles were confined to Raspailiidae-Microcionidae Carter, 1875 -Myxillidae Dendy, 1922 -Agelasidae Verrill, 1907 (Fig. 1B; van Soest 1991). However, uniting this group on the basis of the shared possession of acanthostyles posed some taxonomic problems. van Soest (1991) considered sigmatose microscleres synapomorphic for the group Microcioniidae-Myxillidae-Mycalidae Lundbeck, 1905 -Petrosiidae van Soest, 1980 - Haplosclerida Topsent, 1928, but these are not found in Raspailiidae and Agelasidae. For the raspailiids he attributed this to secondary loss but questioned whether the verticillate acanthostyles found in Agelasidae were homologous. Up to and including Lévi (1973), all authors considered the agelasids to be part of Poecilosclerida. Bergquist (1978), on the basis of reproductive biology and biochemical data, assigned the family to Axinellida. Chombard et al. (1997) found support for this classification using 28S rRNA sequence data. In the same study they also demonstrated a sister relationship between Agelasidae and Astroscleridae. The genus Axinella Schmidt, 1862 has been shown to be polyphyletic using ribosomal and also CO1 barcoding sequences (Gazave et al. 2010b; Morrow et al. 2012). Two groups of Axinella were recovered, one with the type species Axinella polypoides Schmidt, 1862 and another with A. damicornis (Esper, 1794). This latter group, also containing A. corrugata (George and Wilson, 1919) and A. verrucosa (Esper, 1794) is now assigned to CymbaxinellaP (Gazave et al. 2010b) and has been shown to be closely related to agelasids (Morrow et al. 2012).

The acanthostyles in Raspailiidae have a variety of geometries but some are remarkably similar to those found in Microcioniidae. This led Hentschel (1923) to assign Raspailiidae to Poecilosclerida, but other authors (e.g., Ridley and Dendy 1887; Vosmaer 1912) placed Raspailia in Axinellidae. Wilson (1921) emphasized an axially condensed skeleton and specialized ectosomal skeleton as the most important taxonomic characters and included Raspailiidae in Axinellidae. Most subsequent authors followed this classification until Hooper (1991), in his revision of Raspailiidae, returned the family to Poecilosclerida. An increasing number of molecular studies has shown that raspailiid taxa are not closely related to Poecilosclerida s.s. (Erpenbeck et al. 2007a, 2007b, 2007c, 2012). Morrow et al. (2012) using 28S rRNA and CO1 barcoding sequences showed that the raspailiids were sister to a redefined Stelligeridae and that the two families clustered with Axinellidae.

We demonstrate strong support for Raspailiidae being sister group to Stelligeridae (Fig. 2), represented in this analysis by Stelligera spp., Paratimea spp., Halicnemia spp., and Higginsia mixta. At least some species of the genera Halicnemia, Higginsia, Paratimea, and Stelligera share a strikingly similar surface architecture to typical raspailiid species, with large robust styles 2–3 mm long protruding from the surface surrounded by a bouquet of thin spicules, which in different species are variously described as styles, anisoxea, or oxea (Fig. 6A–D). This specialized ectosomal surface architecture appears to be confined to Raspailiidae and Stelligeridae and gives strong morphological support for a close relationship between these two families; however, it is not ubiquitous for all taxa. This highlights the difficulties in defining higher taxonomic groups on the basis of one or only a few morphological characters. In an undescribed species of Paratimea, the centrotylote oxea have fissurate ends; this type of spicule has previously been found only in Halicnemia verticillata and some species of Higginsia and appears to be apomorphic for Stelligeridae.

Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs showing specialized surface architecture of large robust styles or tylostyles that penetrate the surface surrounded by bouquets of smaller, more slender oxea or styles. (A) Halicnemia sp. (Mc5907); (B) Stelligera stuposa (Mc4330); (C) Raspailia hispida (Mc3597); (D) Paratimea sp. (Mc3089). Catalogue numbers refer to Ulster Museum (BELUM) Porifera collection.

Condensed axial skeleton

An axial skeleton consists of a stiff axial region that is clearly distinct from a softer extra-axial region. A cross section through a branch of Axos cliftoni Gray, 1867 illustrates the occurrence of axially condensed skeletons (Fig. 1A–C). van Soest (1991) argued that an axially condensed skeleton represents a functional response of erect branching sponges to the problem of obtaining rigidity. It occurs in Biemnidae, Axinellidae, Raspailiidae, Stelligeridae, Suberitidae Schmidt, 1870, Microcionidae, Trachycladidae, and Hemiasterellidae (Fig. 1C), but within each of these families there are encrusting or cushion-shaped species that do not possess an axially condensed skeleton, thereby lending support to the hypothesis of van Soest (1991).

Proposals for the classification of Heteroscleromorpha

Morrow et al. (2012) proposed the resurrection of Axinellida Lévi, 1953, based mainly on 28S rRNA sequence data. A new definition of the order was formally given to contain Axinellidae s.s., Raspailiidae, and Stelligeridae. The present study finds additional molecular and morphological support for this proposal.

Desmacella cf. annexa Schmidt, 1870 does not group with Biemna Gray, 1867, Neofibularia Hechtel, 1965, or Sigmaxinella Dendy, 1897. Molecular data from the type species of Desmacella Schmidt, 1870 (Redmond et al. 2013, this issue) indicate that D. cf. annexa is representative of the genus and we propose to resurrect Biemnidae (which has seniority over Sigmaxinellidae) for the clade containing Biemna spp., Neofibularia spp., and Sigmaxinella hipposiderus, and use Desmacellidae for species of Desmacella. Hajdu and van Soest (2002) pointed out that Sigmaxinella is distinguished from Biemna mainly by the possession of an axially condensed skeleton. Sigmaxinella is only represented in our CO1 genetree (Fig. 3) by a single species. Any decisions regarding the status of this genus will require additional molecular data from a greater number of species.

We recovered a strongly supported clade containing Biemna and Neofibularia (Fig. 2). Whilst our CO1 tree has a different branching order to our combined 18S-28S rRNA genetree (Fig. 2), it shows strong support for a clade containing Biemnidae and Rhabderemiidae. On the basis of these molecular data and the morphological characters discussed above we propose to formally erect a new order Biemnida.

Biemnida ord. nov. Morrow, 2013

Biemnidae Hentschel, 1923; Rhabderemiidae Topsent, 1928

Encrusting, massive, cup-shaped, fan-shaped, and branching sponges. Megascleres styles, subtylostyles, strongyles, rhabdostyles, or oxea. Spicules typically enclosed by spongin fibers. Reticulate or plumoreticulate choanosomal skeleton, maybe axially compressed. Extra-axial plumose skeleton usually present. Microscleres sigmata, spirosigmata, toxa, microxeas, raphides, or commata. Biemna and Neofibularia cause a dermatitis-like reaction when in contact with bare skin.

The problem of Hadromerida

The “hadromerid” families are found in four well-supported clades (Fig. 1C); one contains Polymastiidae Gray, 1867, a second Clionaidae d’Orbigny, 1851 + Placospongiidae Gray, 1867 + Spirastrellidae Ridley and Dendy, 1886, a third Suberitidae + Halichondriidae. The fourth equates to Hadromerida: it contains Hemiasterellidae + Trachycladidae + Tethyidae + Timeidae. The order Halichondrida is left with only Halichondriidae and Suberitidae. A decision needs to be made whether to erect orders for each of these clades or suppress the order Poecilosclerida and/or Halichondrida and use Hadromerida for the very large clade containing Polymastiidae, Halichondrida, Suberitidae, Clionaidae, Placospongiidae, Spirastrellidae, Poecilosclerida, Trachycladidae, Hemiasterellidae, Tethyidae, and Timeidae; however, this is beyond the scope of this study.

Acknowledgments

The sampling of such a diverse range of species was made possible by loans from the Ulster Museum’s sponge collection; National Cancer Institute (NCI) collection, and the PorTol collection.

Finally, we would like to thank Eduardo Hajdu (Museu Nacional/UFRJ Brazil) and Rob van Soest (formerly Zoological Museum Amsterdam) for the loan of museum specimens and useful taxonomic discussions.

Funding

Christine Morrow’s studentship is funded by the Beaufort Marine Biodiscovery Research Award under the Sea Change Strategy and the Strategy for Science Technology and Innovation (2006–2013), with the support of the Marine Institute, funded under the Marine Research Sub-Programme of the National Development Plan 2007–2013.

Queens University Belfast, School of Biological Sciences and the Beaufort Marine Biodiscovery Programme provided financial support for this research.

The European Community Research Infrastructure Action under the FP7 “Capacities” Specific Programme, ASSEMBLE Grant agreement No. 227799 enabled us to visit and collect specimens at the Observatoire Océanologique de Banyuls. Deepwater samples were collected during cruise CE10004 of RV Celtic Explorer, using the deepwater Remotely Operated Vehicle Holland I.

Porifera Tree of Life (PorToL) project was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DEB awards 0829986, 0829791, 0829783, and 0829763), the SICB Division of Phylogenetics and Comparative Biology, the SICB Division of Invertebrate Zoology, and the American Microscopical Society.

References

- Bergquist PR. Additions to the Sponge Fauna of the Hawaiian Islands. Micronesica. 1967;3:159–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist PR. The Marine Fauna of New Zealand: Porifera Demospongiae, Part 2 (Axinellida and Halichondrida) NZ Dept Sci Ind Res Bull [NZ Oceanogr Inst Mem 51] 1970;197:1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist PR. Sponges. London, UK: Hutchinson; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Borchiellini C, Chombard C, Manuel M, Alivon E, Vacelet J, Boury-Esnault N. Molecular phylogeny of Demospongiae: implications for classification and scenarios of character evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boury-Esnault N. Systematics and evolution of Demospongiae. Can J Zool. 2006;84:205–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas P. 2010. Phylogeny, Taxonomy and Evolution of the Astrophorida (Porifera, Demospongiae) PhD Thesis, University of Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas P, Pérez T, Boury-Esnault N. Sponge systematics facing new challenges. Adv Mar Biol. 2012;61:79–209. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387787-1.00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas P, Xavier JR, Reveillaud J, Schander C, Rapp HT. Molecular Phylogeny of the Astrophorida (Porifera, Demospongiaep) Reveals an Unexpected High Level of Spicule Homoplasy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedro VR, Hajdu E, Correia MD. Three new intertidal sponges (Porifera Demospongiae) from Brazil’s fringing urban reefs (Maceió Alagoas Brazil), and support for Rhabderemia's exclusion from Poecilosclerida. J Nat Hist. Forthcoming [Google Scholar]

- Chombard C, Boury-Esnault N, Tillier S. Reassessment of homology of morphological characters in tetractinellid sponges based on molecular data. Syst Biol. 1998;47:351–66. doi: 10.1080/106351598260761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chombard C, Boury-Esnault N, Tiller S, Vacelet J. Polyphyly of “sclerosponges” (Porifera Demospongiae) supported by 28S ribosomal sequences. Biol Bull. 1997;193:359–67. doi: 10.2307/1542938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Weerdt WH. Phylogeny and vicariance biogeography of North Atlantic Chalinidae (Haplosclerida Demospongiae) Beaufortia. 1989;39:55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Cheung M, Heled J, Kearse M, Moir R, Stones-Havas S, Thierer T, Wilson A. Geneious Pro v47: 2009. ( http://wwwgeneiouscom/) [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004a;32:1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004b;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, Hooper JNA, Wörheide G. CO1 phylogenies in diploblasts and the ‘Barcoding of Life’—are we sequencing a suboptimal partition? Mol Ecol Notes. 2006;6:550–3. [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, Cleary DFR, Voigt O, Nichols SA, Degnan BM, Hooper JNA, Wörheide G. Analysis of evolutionary biogeographical and taxonomic patterns of nucleotide composition in demosponge rRNA. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 2007a;87:1607–14. [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, Duran S, Rützler K, Paul V, Hooper JNA, Wörheide G. Towards a DNA taxonomy of Caribbean demosponges: a gene tree reconstructed from partial mitochondrial CO1 gene sequences supports previous rDNA phylogenies and provides a new perspective on the systematics of Demospongiae. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 2007b;87:1563–70. [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, Hall K, Alvarez B, Büttner G, Sacher K, Schätzle S, Schuster A, Vargas S, Hooper JNA, Wörheide G. The phylogeny of halichondrid demosponges: past and present re-visited with DNA-barcoding data. Org Divers Evol. 2012;12:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, Hooper JNA, List-Armitage SE, Degnan BM, Wörheide G, van Soest RWM. Affinities of the family Sollasellidae (Porifera Demospongiae): II Molecular evidence. Contrib Zool. 2007c;76:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, McCormack GP, Breeuwer JAJ, van Soest RWM. Order level differences in the structure of partial LSU across demosponges (Porifera): new insights into an old taxon. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont JP, Bergquist PR. Structural characters and their use in sponge taxonomy; when is a sigma not a sigma? In: Rützler K, editor. New perspectives in sponge biology. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution Press; 1990. pp. 273–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gazave E, Lapébie P, Renard E, Vacelet J, Rocher C, Ereskovsky A, Lavrov D, Borchiellini C. Molecular Phylogeny restores the supra-generic subdivision of Homoscleromorph sponges (Porifera, Homoscleromorpha) PLoS One. 2010a;5:e14290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazave E, Carteron S, Chenuil A, Richelle-Maurer E, Boury-Esnault N, Borchiellini C. Polyphyly of the genus Axinella and of the family Axinellidae (Porifera: Demospongiaep) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010b;57:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybeal A. Is it better to add taxa or characters to a difficult phylogenetic problem? Syst Biol. 1998;47:9–17. doi: 10.1080/106351598260996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu E, van Soest RWM. Family Desmacellidae Ridley & Dendy 1886. In: Hooper JNA, van Soest RWM, editors. Systema Porifera. A guide to the classification of sponges. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann EF. A revision of the genera with microscleres included or provisionally included in the family Axinellidae; with descriptions of some Australian species Part III. Proc Linn Soc NSW. 1917;41:634–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman WD. Porifera. In: Parker SP, editor. Synopsis and classification of living organisms. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1982. pp. 640–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel E. Erste Unterabteilung der Metazoa: Parazoa Porifera-Schwämme. In: Kükenthal W, Krumbach T, editors. Handbuch der Zoologie Eine Naturgeschichteder Stämme des Tierreiches Vol 1 Protozoa Porifera Coelenterata Mesozoa. Berlin and Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter und Co; 1923. pp. 307–418. fig 288–377. [Google Scholar]

- Hill MS, Hill AL, Lopez J, Peterson KJ, Pomponi S, Diaz MC, Thacker RW, Adamska M, BouryEsnault N, Cárdenas P, et al. Reconstruction of family-level phylogenetic relationships within Demospongiae (Porifera) using nuclear encoded housekeeping genes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e50437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes B, Blanch H. Genus-specific associations of marine sponges with group I crenarchaeotes. Mar Biol. 2007;150:759–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA. Sigmaxinella soelae and Desmacella ithystela, two new desmacellid sponges (Porifera Axinellida Desmacellidae) from the Northwest Shelf of Western Australia with a revision of the family Desmacellidae. North Territ Mus Arts Sci Mon Ser. 1984;2:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA. Character stability systematics and affinities between Microcionidae (Poecilosclerida) and Axinellida. In: Rützler K, editor. New perspectives in sponge biology. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution Press; 1990a. pp. 284–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA. A new species of Rhabderemia Topsent (Porifera: Demospongiae) from the Great Barrier Reef. The Beagle, Records of the North Territ Mus Arts Sci 7, 1990b;1: 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA. Family Rhabderemiidae Topsent 1928. In: Hooper JNA, van Soest RWM, editors. Systema Porifera. A guide to the classification of sponges. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA. Revision of the family Raspailiidae (Porifera: Demospongiae) with description of Australian species. Invertebr Taxon. 1991;5:1179–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JNA, van Soest RWM. Systema Porifera. A guide to the classification of sponges. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner RA. When molecules and morphology clash: reconciling conflicting phylogenies of the Metazoa by considering secondary character loss. Evol Dev. 2004;6:372–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2004.04045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kott P. New and little-known species of Didemnidae (Ascidiacea, Tunicata) from Australia (part I) J Nat Hist. 2004;38:2455–526. [Google Scholar]

- Lafay B, Boury-Esnault N, Vacelet J, Christen R. An analysis of partial 28S ribosomal RNA sequences suggests early radiation of sponges. BioSystems. 1992;28:139–51. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(92)90016-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov DV, Wang X, Kelly M. Reconstructing ordinal relationships in the Demospongiae using mitochondrial genomic data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;49:111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévi C. Sur une nouvelle classification des Démosponges. Compt Rend Hebdom Séan Acad Sci Paris. 1953;236:853–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévi C. Les Clavaxinellides, Démosponges Tétractinomorphes. Arch Zool exp et gén 92 (Notes et Revue 2) 1955:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi C. Étude des Halisarca de Roscoff. Embryologie et systématiquedes démosponges. Arch Zool exp et gén. 1956;93:1–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi C. Ontogeny and systematics in sponges. Syst Zool. 1957;6:174–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi C. Systématique de la classe des Demospongiaria (Démosponges) In: Grassé P-P, editor. Traité de Zoologie Vol. 3 Spongiaires. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1973. pp. 577–632. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow CC, Picton BE, Erpenbeck D, Boury-Esnault N, Maggs CA, Allcock AL. Congruence between nuclear and mitochondrial genes in Demospongiae: a new hypothesis for relationships within the G4 clade (Porifera: Demospongiae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;62:174–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols SA. An evaluation of support for order-level monophyly and interrelationships within the class Demospongiae using partial data from the large subunit rDNA and cytochrome oxidase subunit I. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;34:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond NE, Morrow CC, Thacker RW, Diaz MC, Boury-Esnault N, Cárdenas P, Hajdu E, Lôbo-Hajdu G, Picton BE, Collins AG. Phylogeny and systematics of Demospongiae in light of new small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Integr Comp Biol. 2013;53:388–415. doi: 10.1093/icb/ict078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley SO, Dendy A. Report on the Monaxonida collected by HMS ‘Challenger’ during the years 1873–1876 Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of HMS ‘Challenger’ 1873–6. Zoology. 1887;20:i–lxviii. 1–275 pls I-LI, 1 map. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling EA, Peterson KJ, Pisani D. Phylogenetic-signal dissection of nuclear housekeeping genes supports the paraphyly of sponges and the monophyly of Eumetazoa. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2261–74. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling EA, Robinson JM, Pisani D, Peterson KJ. Where’s the Glass? Biomarkers molecular clocks and microRNAs suggest a 200 million year missing precambrian fossil record of siliceous sponge spicules. Geobiology. 2010;8:24–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Hoover P J, Rougemont A. Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web-Servers. Syst Biol. 2008;75:758–71. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker RW, Hill A, Hill M, Redmond N, Collins AG, Morrow CC, Spicer L, Carmack CA, Zappe M, Bangalore P. Nearly complete 28S rRNA gene sequences confirm new hypotheses of sponge evolution. Integr Comp Biol. 2013;53:373–87. doi: 10.1093/icb/ict071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topsent E. Sur le genre Halicnemia Bowerbank. Mém Soc Zool France. 1897;10:235–51. [Google Scholar]

- Uriz MJ. Deep-water sponges from the continental shelf and slope off Namibia (Southwest Africa): Classses Hexactinellida and Demospongia. Monografías de Zoología Marina. 1988;3:9–157. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM. Deficient Merlia normani Kirkpatrick 1908 from the Curaçao reefs with a discussion on the phylogenetic interpretation of sclerosponges. Bijdr Dierkd. 1984a;54:211–9. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM. Hummelinck PW, van der Steen LJ, editors. Marine sponges from Curaçao and other Caribbean localities. Part III. Poecilosclerida. Uitgaven van de Natuurwetenschappelijke Studiekring voor Suriname en de Nederlandse Antillen. No. 112. Studies on the Fauna of Curaçao and other Caribbean Islands. 1984b;62:1–173. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM. Phylogenetic exercises with monophyletic groups of sponges. p 227–41. In: Vacelet J, Boury-Esnault N, editors. Taxonomy of Porifera from the NE Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea NATO ASI Series G13. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1987. p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM. Toward a phylogenetic classification of sponges. In: Rützler K, editor. New perspectives in sponge biology. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution; 1990. pp. 344–8. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM. Demosponge higher taxa classification re-examined. In: Reitner J, Keupp H, editors. Fossil and recent sponges. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1991. pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM, Boury-Esnault N, Hooper JNA, Rützler K, de Voogd NJ, Alvarez de Glasby B, Hajdu E, Pisera AB, Manconi R, Schoenberg C, et al. World Porifera database. 2013. ( http://www.marinespeciesorg/porifera) on January 20, 2013.

- van Soest RWM, Diaz MC, Pomponi SA. Phylogenetic classification of the halichondrids (Porifera Demospongiae) Beaufortia. 1990;40:15–62. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest RWM, Hooper JNA. Taxonomy phylogeny and biogeography of the marine sponge genus Rhabderemia Topsent, 1890 (Demospongiae Poecilosclerida) In: Uriz M-J, Rützler K, editors. Recent advances in ecology and systematics of sponges. Sci Mar. Vol. 57. 1993. pp. 319–51. [Google Scholar]

- Vosmaer GCJ. On the Distinction between the genera Axinella, Phakellia, Acanthella a.o. Zool Jahrb Jena Suppl. 1912;15:307–22. pls 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ. Does adding characters with missing data increase or decrease phylogenetic accuracy? Syst Biol. 1998;47:625–40. doi: 10.1080/106351598260635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HV. The genus Raspailia and the independent variability of diagnostic features. J Elisha Mitchell Sci Soc. 1921;37:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wörheide G, Erpenbeck D, Menke C. The Sponge Barcoding Project - aiding in the identification and description of poriferan taxa. In: Custódio MR, Lôbo-Hajdu G, Hajdu E, Muricy G, editors. Porifera Research: Biodiversity, Innovation & Sustainability. 2007. Museu Nacional, Série livros 28, Rio de Janeiro. pp. 123–8. [Google Scholar]