Abstract

Background

Currently, the Council of Cooperative Health Insurance (CCHI) is the body responsible for regulating health insurance in the KSA. While the cooperative health insurance schedule (i.e., model policy for health insurance) is available on the CCHI web site, policies related to pharmaceuticals are ambiguous.

Aims

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of health insurance policies provided by health insurance companies in KSA on access to medication and its use.

Settings and Design

This study was descriptive in design and used a survey, which was conducted through face-to-face interviews with the medical managers of health insurance companies.

Methods and Material

The survey took place between March and June, 2011. All 25 insurance companies accredited by CCHI were eligible to be included in the study. Out of these 25 companies, three were excluded from this survey as no response was received.

Results

All the 16 companies responded “Yes” that they had a prior authorization policy; however, their reasons varied. Eight (50%) of the companies were concerned about the duration of treatment. While 10 (62.5%) did not offer additional coverage over the CCHI model policy, the other 6 (37.5%) reported that they could reconcile certain conditions. The survey also demonstrated that 10 insurance companies allowed refilling of medication but with certain limitations. Six out of the 10 permitted refilling within a maximum time of three months, whereas the other four companies did not have any time-based limits for refilling. The other six companies did not allow refilling without prescription.

Conclusions

Although this paper was primarily descriptive, the findings revealed a substantial scope for improvement in terms of pharmaceutical policy standards and regulation in the health insurance companies in KSA. Additionally, the study highlighted such areas to augment the overall quality use of medication, over-prescribing and irrational use of medication. Further research, thus, is definitely needed.

Keywords: Delivery of health care, Saudi Arabia, Health insurance, Health care policy

1. Introduction

The healthcare system in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) ensures free medical coverage to all citizens and expatriates working in the public sector. Under Saudi law, Saudi citizens are entitled to free healthcare. Private-sector employees receive basic healthcare coverage from their employers in the form of insurance policies issued by private insurance companies (Walston et al., 2008). In Saudi Arabia, which had an estimated population of 27 million in 2010, healthcare is delivered by three major providers: the network of hospitals and primary healthcare centers of the ministry of health (MOH); governmental institutions, such as National Guard, Military and Security Forces hospitals; and the private sector. According to recent statistics from the MOH, KSA has a total of 408 hospitals: 244 hospitals are part of the MOH network, 39 hospitals belong to governmental institutions, and 125 belong to the private sector (Central Department of Statistics and Information, 2010; MOH, 2011).

The private health insurance system in Saudi Arabia was the result of the implementation of the Health Insurance Act in 1999. This act aims to control and regulate the provision of health insurance for both Saudi and non-Saudi residents in the Kingdom. The Council of Cooperative Health Insurance (CCHI) is an independent government body established to regulate the health insurance industry in the Kingdom (MOH, 2011).

As stated in article 17 of Health Insurance Act, health insurance can be offered by qualified Saudi insurance companies. Currently, the CCHI has accredited and approved 25 insurance companies. Additionally, the CCHI has issued licenses to five third party administrators (TPAs) and more than 2150 health care providers (CCHI, 2011).

A model health insurance policy is available on the CCHI website. The benefits and limitations of coverage under the CCHI model policy is SR 250,000 ($66,667) per person annually. The coverage is inclusive of services such as consultation, laboratory tests, X-rays, medicines, and other medical necessities as well as follow-up visits and referral for the same illness. Other hospitalization and medical expenses, such as those related to pregnancy and delivery, premature babies, cost of dental treatment, spectacles, renal dialysis, and acute psychological disorders, are subject to certain maximum limits during the term of policy. For example, the maximum coverage for acute psychological disorders is SR 15,000 ($4000) during the term of the policy.

Additionally, the CCHI (CCHI, 2011) has issued general exclusions from the model policy, and conditions related to treatment are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Treatment of any condition as a result of alcohol or drug abuse.

-

2.

General health examinations, vaccinations and/or prophylactic (except which stated by MOH, such as children vaccination etc.).

-

3.

Management of Human Immune Deficiency Virus (AIDS).

-

4.

Treatment of any sexually transmitted disorder (STD).

-

5.

Treatment for cosmetic purposes.

-

6.

Chronic psychological disorders.

-

7.

Treatment of hair fall.

-

8.

Birth control pills.

-

9.

Any treatment connected with fertility and/or sterility and/or impotence and/or contraception and/or hormonal treatment.

-

10.

Management of acne and obesity.

-

11.

Herbal or dietary supplements.

According to the World Health survey data, about half (41–56%) of individuals in low and middle-income countries spend all of their health care expenditures on medicines (Wagner et al., 2011). Recommendations from the second International Conference on Improving Use of Medicines (2004) concluded that the insurance system has a great potential to augment the use of medicines (ICIUM, 2004). In the CCHI model schedule, although medication expenses are covered up to a maximum annual limit of SR 250,000 ($66,667) per person, policies related to prescription drugs, such as refills and pre-authorization for service, are not clearly defined. This paper aims to examine the impact of health insurance policies provided by health insurance companies in KSA on access to medication and its use.

2. Subjects and methods

A questionnaire was used as the main tool of data collection in this study. The questionnaire was developed to cover both the insurance industry and the medication coverage policy. Two qualified pharmacists from Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) were involved in posing the questions of the questionnaire. The questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1.

All 25 companies accredited and listed by CCHI were eligible to be included in the study. Out of these 25 companies, three were excluded from this survey, as they did not respond to the survey request. Further, seven of the remaining companies were represented by a TPA and offered identical insurance policies. Thus, the total number of the companies enlisted in the survey was 16.

The questionnaire was administered through face-to-face interviews with the medical managers of health insurance companies. The survey took place between March and June, 2011. The interview was conducted at the company site or at SFDA. Eight of the 22 companies submitted their completed surveys via email and clarifications, if needed, were sought through phone calls. Owing to prior agreement, the names of the insurance companies have been anonymous.

3. Results

3.1. An overview of insurance companies

In the first part of the questionnaire, seven questions were designed to gain an overview of the health insurance companies operating in Saudi Arabia. Citing reasons of confidentiality, two of the surveyed companies did not respond to the first part. Thus, a total of 14 companies answered the first part of the questionnaire.

The first question pertained to the core insurance business of the companies. Seven of the 14 companies confirmed that health insurance is their core business. The companies were then asked to enumerate their staff numbers in 2009. Nine companies had more than 100 employees and the TPA company, which managed seven health insurance companies, had more than 100 employees. After that, the percentage of the company’s business of health insurance showed that 77% of the companies fall between 20% and 60%. Table 1 shows the percentage of health insurance and the number of companies that fall in this range.

Table 1.

Percentage of health insurance sector as per company.

| Health insurance business (%) | Company(s) |

|---|---|

| ⩽20 | 1 |

| 21–40 | 5 |

| 41–60 | 5 |

| 61–80 | 1 |

| >81 | 2 |

As the companies had different terminologies and prices for the different types of health insurance they offered, direct assessment and comparison of the policies was not possible. With regard to the maximum annual benefit limit per year, 14 companies did not have any maximum limit to drug coverage while two others did not respond. Data collected to determine the number of individuals covered under health insurance in 2009 and 2010 showed that, among 14 companies, more than 5.36 million individuals were covered by private health insurance in 2010, as opposed to more than 3.97 millions in 2009.

3.2. Pharmaceutical coverage policy

The second part of the questionnaire examined policies related to accessing medications. All the 16 companies replied to all the questions in the second part. Results of the 13 questions, in the second part, are detailed as follows:

The purpose of the first question was to determine whether a company had different coverage policies for individuals and companies or institutions. None of the surveyed companies had different coverage policies for individuals and institutions.

The second question was designed to identify the person/committee responsible for including or excluding drugs from coverage at the insurance company. Some companies selected more than one option. Table 2 illustrates that 50% of the insurance companies follow the CCHI model policy.

Table 2.

Inclusion or exclusion of drug coverage.

| Who makes the decision | Company(s)a |

|---|---|

| CCHI model policy | 6 |

| Medical committee | 4 |

| Health services provider | 4 |

| Physician at the company | 4 |

| Pharmacist at the company | 1 |

Companies could select more than one option.

In the third question, the aim was to determine whether the insurance company fully adhered to the CCHI model policy or whether it was flexible to include its own terms into the policy. Results showed that 10 (62.5%) companies did not offer additional coverage over the CCHI model policy. The remaining six (37.5%) companies offered additional coverage depending on customer preferences.

The fourth question assessed the insurance company’s views on drug exceptions (drug not covered). The purpose was to recognize whether the insurance company refers to the general exceptions by CCHI or they may have their own exceptions based on certain justifications. Eleven out of 22 companies followed the exceptions issued by CCHI, but five companies had more exceptions in addition to the ones of CCHI, such as the use of generic drug instead of branded one.

With regard to prior authorization for drugs (fifth question), all the companies confirmed that they had a prior authorization policy but for different reasons. Fifty percent (eight companies) stated that their main concern was the duration of treatment (see Graph 1).

Graph. 1.

Reasons for pre-authorization.∗Companies could select more than one option.

The sixth question was related to the fifth: what is the approximate time taken to receive an approval from the insurance company for a prior authorization? The model policy of the CCHI stated that, “the insurance company should convey the approval request within a period not exceeding sixty minutes from the time of receipt of such request.” Among the surveyed companies, 87.5% indicated that the time taken to approve a prior authorization request was few minutes, whereas 12.5% said that they take 1–2 h for approval.

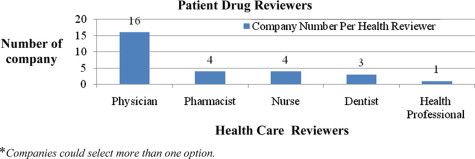

The seventh question asked the type of professional who reviews the patient’s prescription. All the companies have a physician reviewer, 33.3% also had a pharmacist, 33.3% companies had a nurse, 25% employed dentists, and the remaining 8.3% companies involved other health professionals in the review process. Graph 2 shows the distribution.

Graph. 2.

Professionals who review patient medication in insurance companies.

The eighth question was related to the maximum number of drugs that could be prescribed by a physician during a single visit. None of the companies had imposed a limit on the number of drugs per prescription.

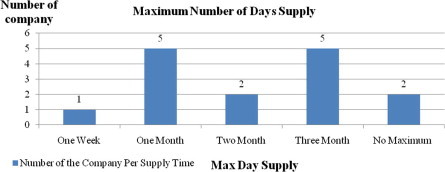

Question nine was related to the maximum number of days, as a base line, for which a drug could be prescribed. The responses were as follows: 31.25% of the companies had defined one month as the upper limit; 31.25% allowed a drug to be prescribed for a maximum of three months; 12.5% chose two months; 12.5% did not have a maximum limit; and 6.25% indicated one week as the upper limit (see Graph 3).

Graph. 3.

Maximum number of days that a drug can be prescribed.

The tenth question assessed the importance of a drug being covered or listed in the Saudi National Formulary (SNF). Of the companies, 18.75% were not concerned about whether a drug was registered or not. The rest of the companies indicated their insurance policies only covered registered drugs.

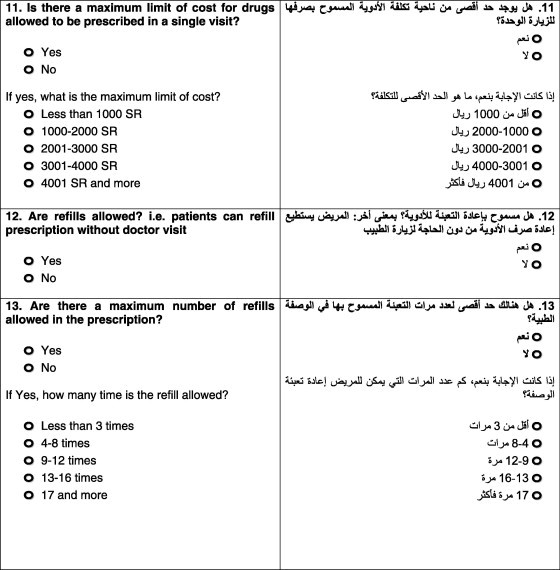

Question eleven pertained to the maximum cost of drugs that could be prescribed during a single visit. No limits were placed by 81.25% of the companies, and other companies imposed maximum limits for different reasons: less than SR 1000 ($267), based on the condition, class of drug, or depending on the policy.

The twelfth and the thirteenth questions concerned the ability of patients to refill prescriptions without a doctor visit and the maximum number of refills allowed. Ten of the 16 companies permitted refilling with some limitations: six allowed refilling up to a maximum of three months, whereas the other four companies did not have time limits. The remaining six surveyed companies did not allow refilling without prescription.

4. Discussion

While medical expenses in the CCHI model policy are subject to a maximum annual benefit limit per person (i.e., SR 250,000 ($66,667)), many issues related to prescription drugs, such as refills, quantity, pre-authorization cases etc., are still vague. It is also not clear if an insurance company can modify the pharmaceutical terms in a policy or if it must fully follow the CCHI model policy. A similar ambiguity exists in the case of general exceptions. This paper, therefore, was carried out to ascertain the gaps in the current medication coverage authorized by insurance companies in the KSA. Issues can thus be highlighted and appropriate recommendations generated to improve the overall quality of medication use. This research is, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic description of the private insurance industry in Saudi Arabia.

The overall results indicate that there are inconsistencies in the pharmaceutical coverage in the health insurance policy. One relevant example is query number 10 in the second part of the survey, which asks for the importance of a drug being listed in the SNF for coverage. The outcomes were contradictory, as demonstrated in the results section. Two leading insurance companies, for instance, reported that registered drugs are not necessarily included in their system as there is no definite regulation in the CCHI that forces an insurance company to cover only registered drugs. While there is no such stipulation in the CCHI concerned with registered medications, medical health providers should prescribe registered medications as per the MOH regulation. According to article number 19 of the Institutions and Pharmaceutical Products Law cited by the SFDA, “consumption and utilization of pharmaceutical and herbal products is prohibited prior to registration by SFDA” (SFDA, 2011). Accordingly, and in light of this regulation, an insurance company should have the right to refuse the non-approved drugs in Saudi Arabia.

The responses to the fifth question in the second part of the questionnaire also offer a valuable insight. This question on prior authorization for medications was included to gain an understanding of the information that insurance companies need before they decide to approve a drug. Two factors came to the fore: The first was the duration of intake. If the medication being prescribed had to be consumed for one month, prior authorization was required. Some insurance companies, however, extended this duration to two months or more. This is possibly to accommodate chronic disorders such as hypertension and diabetes. The second significant aspect was cost. Six companies reported that if the price of prescribed medication exceeded SR 500 ($133.3), as a standard, then a pre-authorization process was needed. Other factors that were also listed by insurance companies included cosmetic reasons, drugs with age limits, and medications excluded under the CCHI. Monitoring the consumption of all chronic medications was one of the major justifications that led insurance companies to apply the pre-authorization system. In terms of the prior authorization of medication prescriptions, we believe that the above inconsistencies are due to the lack of CCHI particular guidelines.

Having discussed these examples with regard to standards of the pharmaceutical coverage of health insurance policies, it is important to argue for the maximum limit on the number of drugs prescribed in a single prescription on a single visit. Question eight in the second part of our survey dealt with this matter, and all insurance companies pointed out that there is no maximum limit for the number of drugs per prescription. While the majority of insurance companies verified that this, basically, depends on the indication as per physician prescription, this may lead to the problem of overprescribing. A pilot study was conducted in Saudi Arabia to examine the prescribing pattern of ambulatory care physicians. The study revealed a tendency to overprescribe certain categories of drugs, which could lead to serious adverse reactions and overdosing (Bawazir, 1993). Further retrospective review in Saudi Arabia identified the need to rationalize the use of drugs such as simple analgesics, antipyretics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to lessen the serious adverse effects of overprescribing (Al-Homrany and Irshaid, 2007). Medical professionals, working in health insurance companies, play an important role in verifying the clinical needs of medication written by medical providers, and thus minimizing the problem of overprescription.

Even though treatment of the Human Immune Deficiency Virus (AIDS/HIV) patients is listed under general exclusions by the CCHI, the matter is entirely under the control of the MOH. In contrast, while treatment of STDs is one of the most under recognized health problems worldwide, it is listed under CCHI general exceptions and do not have a prevention program run by MOH as in the case of HIV/AIDS. One descriptive case series reported and recommended that health education, early diagnosis and treatment, are the core strategies for preventing STDs in Saudi Arabia (Madani, 2006). Management of obesity is another critical exemption from the CCHI list. Evidence from systematic reviews has demonstrated that obesity is associated with an elevated risk for most of the major health problems, including cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (Lenz et al., 2009). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overweight and obesity are the fifth leading risks for global deaths, and at least 2.8 million adults die each year because of being overweight or obese (WHO, 2012). A national epidemiological health survey conducted in KSA stressed that an aggressive campaign against obesity is fundamental (Al-Nozha et al., 2005). Chronic psychological disorders, treatment of impotence and management of acne are other examples of questionable exclusions. We deem that the omission of such health problems by the CCHI and health insurance companies is inappropriate from the viewpoint of public health. Consequently, an urgent revision of the exclusion list is required.

Notwithstanding our study did not attempt or design to compare the Saudi case with similar international bodies or studies conducted abroad, some international health insurance systems can be briefly examined as examples. Medicare benefits in the US, which are coordinated by private health insurance and subsidized by the federal government, are divided into four major categories: Part A (hospital coverage), Part B (medical insurance), Part C (Medicare advantage plan), and Part D (prescription drug plans). Medicare Part D offers outpatient prescription drug coverage through private plans, and these plans may vary in premiums, deductibles, formulary design, and the use of management tools. Plans cover both generic and brand name prescriptions drugs. With respect to the formulary, all drugs in six categories are protected: antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals (HIV/AIDS treatment), immunosuppressants and anticancer drugs. Otherwise, each Medicare drug plan has its own list of covered prescription drugs, called a plan’s formulary. For safety and cost reasons, certain cases may require prior authorization including step therapy and quantity limits. This contradicts with the Saudi case (CCHI) as chronic psychological diseases and treatment of STD are listed under the exclusion list, whereas these treatments are entirely protected in the US policy. Further example among European region, France has a private insurance operated as a complement to the public insurance system, which aims to supplement cost sharing and expand benefits. France has a special program to accommodate thirty chronic conditions, and thereby eliminating cost sharing for covered people. Regardless of price, prescription drugs in French health insurance are covered with “value-based” design (The Official US Government Site for Medicare, 2012; Lau and Stubbings, 2012; Schoen et al., 2010; Lau et al., 2011). In Middle East, while the Abu Dhabi experience with health insurance in United Arab Emirates (UAE) is relatively similar to CCHI policy, there are more details with respect to pharmaceutical coverage services as well as further exclusions. Although the annual maximum limit for the basic healthcare services is AED 250,000 ($66,667) for every person, 70% of the cost of medicine is covered up to a maximum of AED 1500 per year provided that the patient settles 30% of the cost of every prescription. In addition to this, the health insurance company’s prior approval is required for prescriptions the cost of which exceeds AED 500. Unexpectedly, treatment and services for smoking cessation programs and the treatment of nicotine addiction are excluded from basic healthcare services in Abu Dhabi health insurance authority (Health Authority of Abu Dhabi, 2012).

We assert that the health insurance system has an essential role in improving the overall user access to and utilization of pharmaceuticals as well as in health outcomes. A systematic review of current evidence published in 2011 showed that insurance has been associated with increased percentage of prescriptions truly filled, reduced probability of gaps in medical treatments, increased use of drugs in patients with chronic diseases, and enhanced adherence to a prescribed regimen. This systematic review also stated that some scientific studies determined that the level of blood glucose was better controlled in insured diabetic patients as they had more insulin doses per week, whereas patients who suffered from high blood pressure had an increased possibility of receiving antihypertensive treatment and hence having their blood pressure controlled (Faden et al., 2011).

This study had three major limitations. First, the responses to certain questions may be superficial because of the time constraints faced by the medical managers of the insurance companies. Second, certain respondents did not provide complete data because of the confidentiality policies of their insurance companies; however; this was in relation to the first part of the survey, which was concerned with an overview of health insurance companies operating in the KSA. Further, as our purpose was primarily to undertake a descriptive rather than a comprehensive assessment, this paper provides an opportunity to further explore pharmaceutical coverage by health insurance companies. This explains the rational of the inability to collect considerable amount of data.

In conclusion, the findings addressed a substantial scope for improvement in terms of the pharmaceutical policy of health insurance companies in Saudi Arabia. In addition, the study highlighted such areas to augment the overall quality use of medication, and thus further research is necessary to assess the influence of health insurance policies on access to medication. Proper monitoring and evaluation of CCHI exclusion list is needed.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our sincere thanks to Dr Abdullah Alshareef and Dr Mohammed Alnuaim and from CCHI for their support to carry out this research. We also would like to thank the managers of the health insurance companies who participated in this survey, for their assistance, help and time during the data collection.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Appendix A. Pharmaceutical policy questionnaire for medical insurance

References

- Al-Homrany M.A., Irshaid Y.M. Pharmacoepidemiological study of prescription pattern of analgesics, antipyretics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at a tertiary health care center. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nozha M.M., Al-Mazrou Y.Y., Al-Maatouq M.A., Arafah M.R., Khalil M.Z., Khan N.B., Al-Marzouki K., Abdullah M.A., Al-Khadra A.H., Al-Harthi S.S., Al-Shahid M.S., Al-Mobeireek A., Nouh M.S. Obesity in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:824–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawazir S.A. Prescribing patterns of ambulatory care physicians in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 1993;13:172–177. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1993.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Council of Cooperative Health Insurance (CCHI), 2011. Available from URL: <http://www.cchi.gov.sa>, (accessed on 01.06.2011).

- Central Department of Statistics & Information, 2010. Available from URL: <http://www.cdsi.gov.sa/english/index.php>, (accessed on 05.09.2011).

- Faden L., Vialle-Valentin C., Ross-Degnan D., Wagner A. Active pharmaceutical management strategies of health insurance systems to improve cost-effective use of medicines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of current evidence. Health Policy. 2011;100:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Authority of Abu Dhabi, 2012. Available from URL: <http://www.haad.ae/haad/Portals/0/Health%20Regulation%20Laws/Book2_En/index.html>, (accessed on 26.06.2012).

- Second International Conference of Improving Use of Medicines (ICIUM). ICIUM 2004 Conference Recommendations: Insurance Coverage. Available from URL: <http://archives.who.int/icium/icium2004/recommendations.html>, (accessed on 11.01.2012).

- Lau D.T., Stubbings J. Medicare part D research and policy highlights, 2012: impact and insights. Clin Ther. 2012;34:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D.T., Briesacher B.A., Touchette D.R., Stubbings J., Ng J.H. Medicare part D and quality of prescription medication use in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:797–807. doi: 10.2165/11595250-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz M., Richter T., Muhlhauser I. The morbidity and mortality associated with overweight and obesity in adulthood: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:641–648. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani T.A. Sexually transmitted infections in Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (MOH), 2011. Available from URL: <http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/Indicator/Pages/default.aspx>, (accessed on 05.09.2011).

- Schoen C., Osborn R., Squires D., Doty M.M., Pierson R., Applebaum S. How health insurance design affects access to care and costs, by income, in eleven countries. Health Aff. 2010;29:2323–2334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA), 2011. Available from URL: <http://www.sfda.gov.sa/NR/rdonlyres/EE17CB48-AAE0-4064-B11D-E40FCD3FE27/0/InstitutionsandPharmaceuticalProductsGuidelines.pdf->, (accessed on 05.09.2011).

- The Official U.S. Government Site for Medicare, 2012. Available from URL: <http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/11109.pdf->, (accessed on 04.06.2012).

- Wagner A.K., Graves A.J., Reiss S.K., Lecates R., Zhang F., Ross-degnan D. Access to care and medicines, burden of health care expenditures, and risk protection: results from the World Health Survey. Health Policy. 2011;100:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walston S., Al-Harbi Y., Al-Omar B. The changing face of healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:243–250. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2012. Available from URL: <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html->, (accessed on 01.05.2012).