Abstract.

The hemodynamic response to neuronal activation is a well-studied phenomenon in the brain, due to the prevalence of functional magnetic resonance imaging. The retina represents an optically accessible platform for studying lamina-specific neurovascular coupling in the central nervous system; however, due to methodological limitations, this has been challenging to date. We demonstrate techniques for the imaging of visual stimulus-evoked hyperemia in the rat inner retina using Doppler optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography. Volumetric imaging with three-dimensional motion correction, en face flow calculation, and normalization of dynamic signal to static signal are techniques that reduce spurious changes caused by motion. We anticipate that OCT imaging of retinal functional hyperemia may yield viable biomarkers in diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy, where the neurovascular unit may be impaired.

Keywords: optical coherence tomography, retina, hemodynamics, angiography, ophthalmology, Doppler, neurovascular coupling

1. Introduction

In the central nervous system, neurovascular coupling is initiated by neurotransmitter release at the synapse, which eventually leads to the control of contractile elements that surround vasculature, typically arterioles and capillaries.1 The resulting local increase in blood flow is called functional hyperemia. While the brain has been used extensively to study functional hyperemia, the inner retina represents an under-utilized model system for investigating this phenomenon. Laser Doppler flowmetry has been applied to study retinal blood flow2 and neurovascular coupling in the optic nerve head.3 Recently, laser speckle imaging and confocal microscopy were shown to image stimulus-induced blood flow and diameter changes in the inner retina.4 Fundus imaging studies, while lacking depth resolution, have revealed reflectance changes suggesting that blood volume increases in response to a light stimulus.5 A retinal blood flow response to a flicker stimulus was suggested using cross-sectional Doppler optical coherence tomography (OCT) in human subjects.6 Using a volumetric imaging protocol in vivo, OCT signal from the photoreceptors was shown to change in response to a light stimulus7; but so far, no robust inner retinal changes have been conclusively demonstrated with OCT in vivo.

In this work, we demonstrate multiparametric imaging of visual stimulus-evoked hyperemia including blood flow, vessel diameter, and vascular red blood cell content/speed. We perform asynchronous volumetric imaging during repeated stimulus trials, and use time-series analysis techniques derived from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)8 to determine trial-locked responses.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal protocols were approved by the animal care and use committee where these experiments were performed. Long–Evans rats (250 to 320 g) were anesthetized with 40 to alpha-chloralose i.v., maintained at 37°C, cyclopleged with 1% tropicamide (Mydriacyl), and paralyzed with rocurronium. Peribulbar irrigation with 2% lidocaine was further used to reduce motion artifacts. During imaging, a contact lens was gently placed on the cornea with goniosol. Rats were ventilated at 0.7 Hz with 85% air and 15% oxygen, and arterial blood pressure was monitored (90 to 130 mmHg). End-tidal was monitored with a capnometer and maintained below 40 mmHg. Rats were immobilized in a custom-made stereotactic frame during imaging.

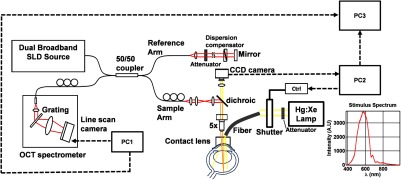

A 1310 nm spectral/Fourier domain OCT microscope was constructed for in vivo imaging of the rat’s retina9 with 7.5 μm transverse resolution, as shown in Fig. 1. A longer wavelength was used to avoid possible stimulation of the retina by the imaging system.10 The light source consisted of two superluminescent diodes combined, using a fiber coupler to yield a bandwidth of 150 nm. The measured axial (depth) resolution in tissue was 3.8 μm. A spectrometer with a 1024-pixel InGaAs line scan camera (Goodrich Sensors Unlimited, Inc., Princeton NJ) was operated at and controlled by a first computer (PC1). The power of the OCT beam on the sample was 1 mW, and the sensitivity was 96 dB. A square-wave flickering light stimulus was generated for 10 s with a fiber light source (Hg:Xe lamp) and a mechanical shutter controlled by a second computer (PC2). The maximum flicker intensity at the retina was estimated to be , while the minimum intensity between stimuli was . The stimulus spectrum is shown in Fig. 1. Comparable stimulus protocols and experimental designs are frequently used in the literature to study functional hyperemia in the rat retina.4,11,12 Uniform illumination of the retina was confirmed by imaging the retina onto a CCD camera connected to PC2. Repeated OCT volumes for angiography () or Doppler OCT () were acquired during runs of 10 stimuli separated by 25 s. In one run, a stimulus frequency of 12 Hz was used, while in the other run, stimulus frequencies between 6 and 18 Hz were generated in a random order to test for frequency dependence of the response.13 All triggers were collected along with the blood pressure and capnometer readings by a third computer (PC3). Figure 2 shows the asynchronous stimulus and scanning protocol for angiography. Jittered acquisition and stimulation protocols, similar to the ones employed here, are routinely used in fMRI to achieve a higher effective temporal resolution when responses are repeatable14 across trials.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of OCT system and microscope. OCT frame and stimulus triggers from PC1 and PC2, respectively, are acquired by a third computer (PC3). The stimulus spectrum is plotted in red.

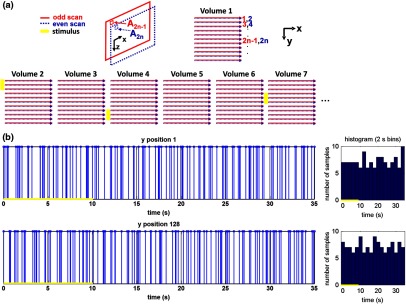

Fig. 2.

(a) Scanning protocol repeatedly generates volumetric OCT angiograms (acquired by scanning each -position twice) asynchronously with respect to the stimulus trials. From trial to trial, each -position is, therefore, sampled at a different time with respect to the stimulus. (b) The blue lines in the stem plots (left) and histograms with 2-s bins (right) show distributions of sampling times of different -positions relative to the stimulus, shown in yellow. Data from a run of 10 trials are shown.

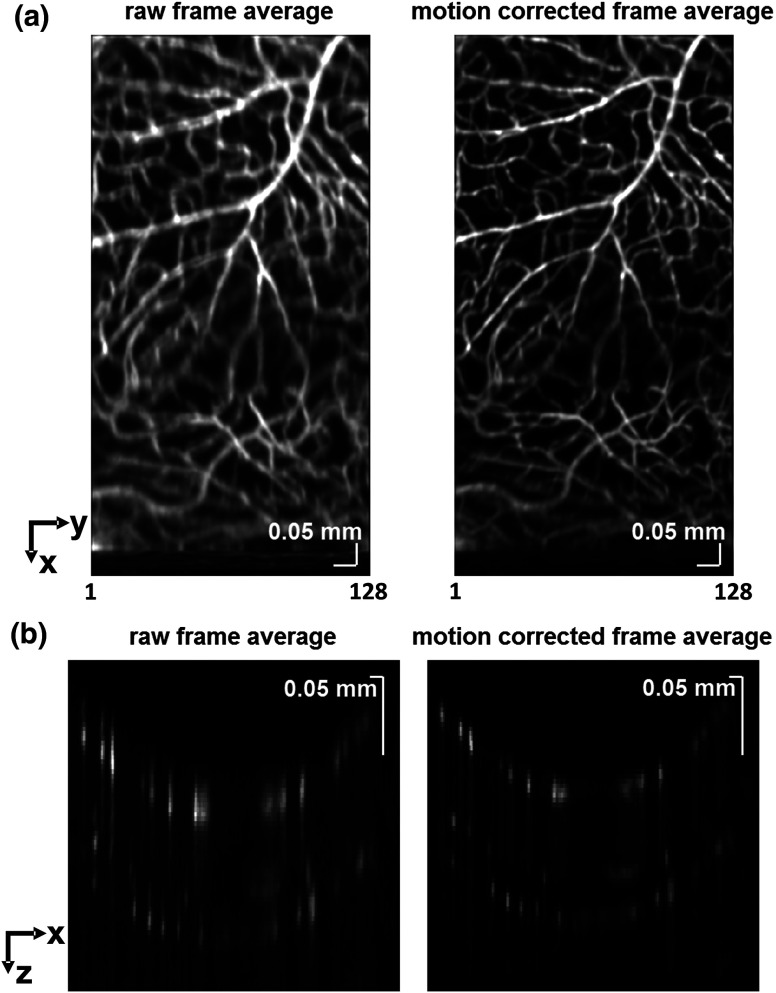

Figure 3 shows the effects of motion correction on the angiograms. Motion correction was achieved by volumetric cross-correlation of individual volumes to determine the (, , ) shift relative to the first acquired volume. After motion correction, residual motion was on the order of a few microns, as can be seen from the width of the capillaries in the motion-corrected volumetric angiograms [Fig. 3(a) and 3(b)].

Fig. 3.

After three-dimensional correlation of volumes and motion correction to maximize the cross-correlation, motion is significantly reduced, as can be seen from averaging all 129 en face inner retinal vasculature projections (a) or all 129 individual cross-sectional angiograms from the same -position (b).

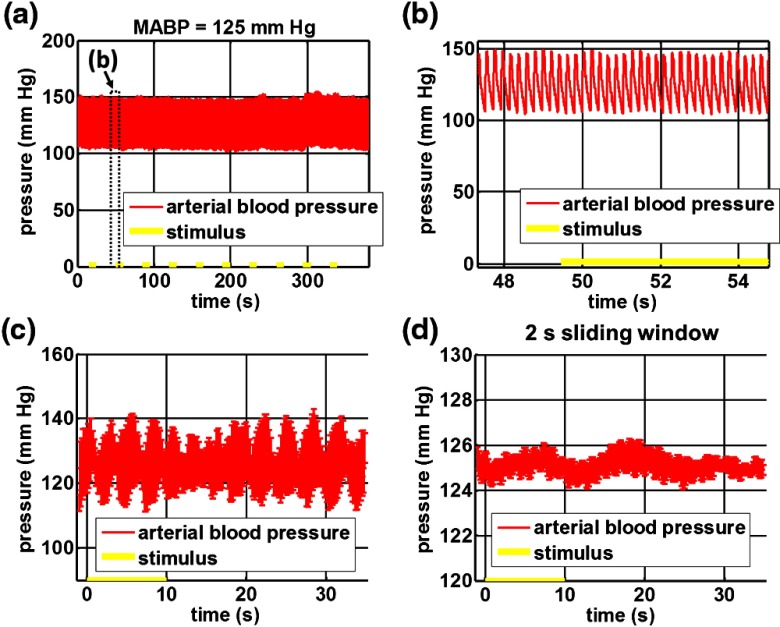

Figure 4 shows the investigation of possible blood pressure variations synchronous with stimulus presentation. Figure 4(a) shows an arterial blood pressure trace during a single run with 10 trials. Figure 4(b) shows pulsations due to the heartbeat. Figure 4(c) shows arterial blood pressure averaged over all trials (), while Fig. 4(d) shows arterial blood pressure filtered by a 2-s sliding window, and then averaged over all trials (). These data show that there is no systematic change in the blood pressure during the stimulus. Furthermore, a comparison of Fig. 4(c) and 4(d) suggests that the measuring of flow by en face integration during multiple heartbeats (which has the effect of temporal averaging or filtering) may reduce pulsatile flow variation associated with the heartbeat.

Fig. 4.

(a) Arterial blood pressure trace during a single run with 10 stimulus trials. The mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was 125 mmHg. (b) Zoom of the boxed region in (a) shows pulsations due to the heartbeat. (c) Arterial blood pressure, averaged over all trials (), shows no systematic change in response to the stimulus. (d) Applying a 2-s sliding window filter before averaging over trials () results in comparably less variation, but still shows no systematic change in response to the stimulus. A variance reduction in flow measurements similar to that observed in (c, d) occurs when integrating velocity over the vessel cross-section during multiple heartbeats.

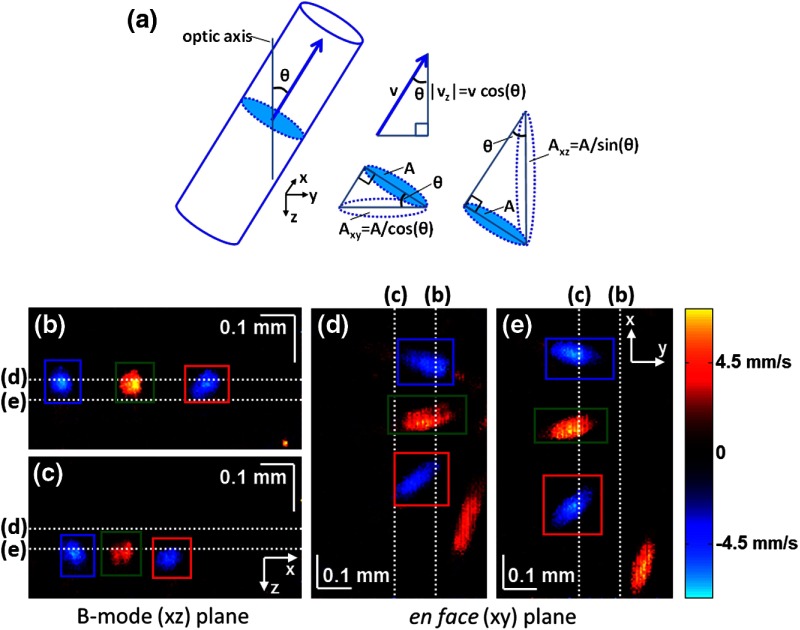

We leverage two key advances to provide robust measurements of hemodynamics. The first advance is that transverse (en face) measurements of blood flow changes are less motion-sensitive than B-mode measurements of blood flow changes. It has previously been shown that en face methods are preferred for absolute blood flow changes15; here, we argue that en face methods are preferred for relative blood flow changes as well. First, we assume that the vessel angle with respect to the optic axis is , as shown in Fig. 5(a), and that motion causes changes in this angle. Relative flow is proportional to both cross-sectional area and mean velocity. For relative blood flow calculated in the B-mode () plane, the vessel cross-sectional area varies as , and the mean velocity axial projection varies as , causing relative flow to have an angular dependence of . Hence, for relative blood flow calculated in the B-mode plane

| (1) |

Fig. 5.

(a) Geometric drawing showing how velocity axial projection and cross-sectional area depend on vessel angle. (b, c) For relative flow determined in the B-mode plane, the velocity axial projection and vessel area change in the same direction when the vessel angle changes due to a 100-μm transverse shift. However, for relative flow determined in the en face plane (d, e), the velocity axial projection and vessel area change in opposite directions. Due to this counterbalancing effect, relative en face flow had a standard deviation of 10%, whereas relative B-mode flow had a standard deviation of 28% for a transverse shift of 100 μm near the optic nerve head (). Color-coded boxes are used to designate the same vessels in different planes.

Thus, as shown in Fig. 5(b) and 5(c), cross-sectional area and mean velocity axial projection change in the same direction when changes, thus exacerbating relative flow noise. The effect of angular changes on flow calculated in the B-mode plane is most pronounced near . By comparison, for relative blood flow calculated in the en face () plane, the vessel cross-sectional area varies as , and the mean velocity axial projection varies as . Hence, as shown in Fig. 5(d) and 5(e), the vessel cross-sectional area and the mean velocity axial projection change in opposite directions to compensate each other mitigating relative flow noise. Hence, for relative blood flow calculated in the en face plane

| (2) |

For these reasons, we found that relative en face flow had a standard deviation of 10%, whereas relative B-mode flow had a standard deviation of 28% for a transverse shift of 100 μm near the optic nerve head ().

The second advance is that OCT signal can be separated into static and dynamic components16 via a complex high-pass filter along the slow axis.17 More specifically, we estimate the dynamic signal by taking a point-wise complex difference between consecutive frames acquired at the same location:

| (3) |

and represent the axial phase-corrected complex OCT signal amplitudes at the th -position. We estimate the static signal by excluding pixels where the dynamic signal exceeds a threshold .

| (4) |

Here “dynamic” signal is defined as any component that varies faster than the timescale (the interframe time for angiography). For decorrelation due to transverse motion, this corresponds to a speed of . If changes during activation are purely hemodynamic, dynamic scattering may increase or decrease due to the increase or decrease in red blood cell content and speed, while intrinsic static scattering properties remain unchanged. Artifacts such as papillary constriction would have similar effects on detected signals from both dynamic blood cells and the adjacent static tissue. The static (nonvascular) signal thus serves as a convenient “reference” to compensate artifacts in the dynamic signal and reveals stimulus-evoked changes.

3. Results and Discussion

As residual motion is on the order of microns, masks can be defined to distinguish dynamic signal [Eq. (3), mostly due to red blood cells] from static signal [Eq. (4), due to neuronal, glial, and possibly endothelial and smooth muscle tissue]. Figure 6(a) shows that normalization of the dynamic signal to the static signal reduces artifacts and reveals intrinsic changes related to functional hyperemia. Exemplary images of the dynamic and static signals, determined from Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively, are shown. As the dynamic signal consists of scattering signal components varying faster than a 7-ms timescale, both an increase in red blood cell content and an increase in speed (through increased Doppler shift or decorrelation rate) may account for the observed changes.17 Arterial speeds are expected to be larger than , meaning that after 7 ms, the complex-valued signal is already uncorrelated. Therefore, flow speed changes minimally affect the dynamic signal, as determined by Eq. (3). Averaged angiograms at baseline and during activation revealed that arterial diameter also increases, as shown in Fig. 6(b)–6(d). Diameter changes were quantified manually along the arterial tree at baseline and during activation in Fig. 6(e) ( to 11.0%, ).

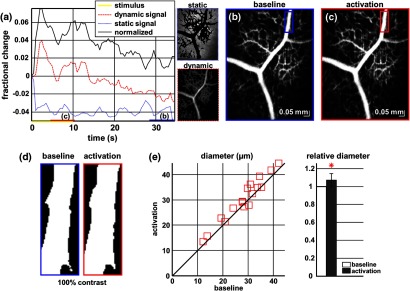

Fig. 6.

OCT angiography of functional hyperemia caused by a 10-s, global 12-Hz light stimulus. (a) The dynamic signal (red-dashed line) is corrupted by motion artifacts. A vascular mask is created to distinguish static and dynamic signals, and the dynamic signal is normalized to the static signal (blue-dotted line) to remove motion artifacts revealing intrinsic dynamic scattering changes (black-solid line). Comparison of averaged angiograms at baseline (b) and during activation (c) shows evidence of arterial dilation (d). The baseline and activation time windows are marked in (a). (e) Diameter changes were manually quantified along the arterial tree.

Figure 7 shows imaging of blood flow changes during activation using the method of en face integration.15 Figure 7(a) shows an angiogram with a white arrow pointing to a vessel whose flow was measured. Figure 7(b) and 7(c) show en face Doppler OCT images of the vessel at baseline and during peak activation. Absolute flow was calculated by integrating the velocity axial projection over the en face plane.15 Figure 7(d) shows the absolute flow time series during all 10 stimuli along with predictions determined by fitting a linear model to the data. A third-order polynomial was included in the linear model to account for baseline fluctuations. Figure 7(e) shows the fractional flow change averaged across all 10 trials. Relative dynamic scattering changes [Fig. 6(a)] were smaller than relative flow changes [Fig. 7(e)]. Figure 7(f) shows a preliminary investigation of the stimulus frequency dependence of the time-integrated responses between 6 and 18 Hz.

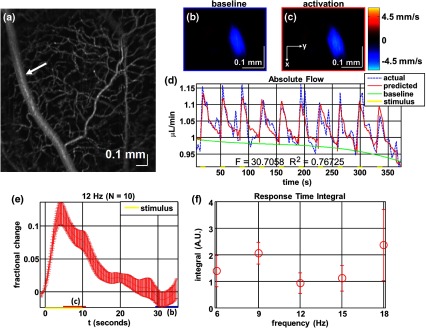

Fig. 7.

Doppler OCT absolute flow measurement of functional hyperemia caused by a 10-s global light stimulus. (a) OCT angiogram with a white arrow showing the vessel chosen for flow measurement. (b, c) Averaged en face Doppler OCT image of vessel at baseline (29 to 35 s) and activation (5 to 11 s). (d) Absolute flow time series (blue-dashed line) with predictions from a linear model (red-solid line). The linear model was applied to determine both the stimulus response and baseline drift (green-solid line). (e) Fractional change time course (.) over 10 trials at a stimulus frequency of 12 Hz with baseline (b) and activation (c) time windows marked. (f) Preliminary investigation of frequency dependence of response time integral (two trials for each frequency, ).

We note some limitations of our techniques here. The strategy of static signal normalization is valid only if intrinsic scattering properties of static tissue do not change appreciably due to activation. It is conceivable that if blood volume increases, retinal tissue is compressed, and therefore, scattering properties may change. However, in our previous studies of functional OCT changes in the retina, we were unable to detect any corresponding inner retinal changes.7 So-called “fast optical signal” changes,18 resulting directly from neuronal activity and membrane polarization changes, are likely too small to be significant here.

Overall, we observed repeatable blood flow, diameter, and dynamic scattering increases in the inner retina during a visual light stimulus. Our results strongly suggest that these are hemodynamic responses in the inner retina caused by the visual stimulus. Similar stimulus protocol and experimental designs have been used in the literature to evaluate visual stimulus-evoked inner retinal hemodynamic changes.4,11,12 Moreover, we observed no systemic physiological changes (such as blood pressure changes) synchronized with the stimulus that could account for the observed responses [Fig. 4(c) and 4(d)]. The time courses and magnitudes of the measured responses are consistent with previous studies in the same species.4,11,12 However, we also observed a weak flicker frequency dependence of the blood flow response time integral [Fig. 7(f)], suggesting that the evoked response may be due, at least in part, to the increase in average luminance during stimulation.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, methodologies for imaging the inner retinal hemodynamic response to a light stimulus in the rat retina were demonstrated. Volumetric imaging and three-dimensional correlation significantly reduced motion artifacts. En face measurements of relative flow changes were found to be robust against motion. Normalization of the dynamic signal to static signal mitigated spurious changes from residual accommodation, pupil constriction, or axial motion. We anticipate that the techniques presented here can be applied to study comparable hemodynamic responses in human subjects.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from the NIH (R00NS067050, R01EB001954), the AHA (IRG5440002), and the GRF Catalyst for a Cure 2, and thank Maria Angela Franceschini and Bruce Rosen for general support.

References

- 1.Attwell D., et al. , “Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow,” Nature 468(7321), 232–243 (2010). 10.1038/nature09613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riva C. E., et al. , “Blood velocity and volumetric flow rate in human retinal vessels,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 26(8), 1124–1132 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riva C. E., Logean E., Falsini B., “Visually evoked hemodynamical response and assessment of neurovascular coupling in the optic nerve and retina,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 24(2), 183–215 (2005). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srienc A. I., Kurth-Nelson Z. L., Newman E. A., “Imaging retinal blood flow with laser speckle flowmetry,” Front. Neuroenerget. 2, 128 (2010). 10.3389/fnene.2010.00128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schallek J., Ts’o D., “Blood contrast agents enhance intrinsic signals in the retina: evidence for an underlying blood volume component,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52(3), 1325–1335 (2011). 10.1167/iovs.10-5215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., et al. , “Flicker-induced changes in retinal blood flow assessed by Doppler optical coherence tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(7), 1852–1860 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.001852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan V. J., et al. , “In vivo measurement of retinal physiology with high-speed ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Lett. 31(15), 2308–2310 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.002308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worsley K. J., Friston K. J., “Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited--again,” Neuroimage 2(3), 173–181 (1995). 10.1006/nimg.1995.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhi Z., et al. , “Volumetric and quantitative imaging of retinal blood flow in rats with optical microangiography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(3), 579–591 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.000579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bizheva K., et al. , “Optophysiology: depth-resolved probing of retinal physiology with functional ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103(13), 5066–5071 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0506997103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra A., Hamid A., Newman E. A., “Oxygen modulation of neurovascular coupling in the retina,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108(43), 17827–17831 (2011). 10.1073/pnas.1110533108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih Y. Y., et al. , “Lamina-specific functional MRI of retinal and choroidal responses to visual stimuli,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52(8), 5303–5310 (2011). 10.1167/iovs.10-6438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falsini B., Riva C. E., Logean E., “Flicker-evoked changes in human optic nerve blood flow: relationship with retinal neural activity,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43(7), 2309–2316 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amaro E., Jr., Barker G. J., “Study design in fMRI: basic principles,” Brain Cogn. 60(3), 220–232 (2006). 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srinivasan V. J., et al. , “Quantitative cerebral blood flow with optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Express 18(3), 2477–2494 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.002477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang R. K., “Three-dimensional optical micro-angiography maps directional blood perfusion deep within microcirculation tissue beds in vivo,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52(23), N531–N537 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/23/N01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivasan V. J., et al. , “Rapid volumetric angiography of cortical microvasculature with optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Lett. 35(1), 43–45 (2010). 10.1364/OL.35.000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen L. B., Keynes R. D., Hille B., “Light scattering and birefringence changes during nerve activity,” Nature 218(5140), 438–441 (1968). 10.1038/218438a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]