Abstract

Importance of the field

Despite the extraordinary clinical benefits of HAART, the prospect of life-long antiretroviral regimen poses significant practical problems, which has spurred an interest in developing new drugs and strategies to treat HIV infection and to eliminate persistent viral reservoirs. RNAi is a highly potent natural gene silencing mechanism that has emerged as a novel therapeutic possibility for HIV.

Areas covered in this review

Our aim is to discuss the recent progress in overcoming the hurdles for translating transient and stable RNAi enabling technologies towards clinical applications in HIV infection and the review covers literature from the past 2–3 years.

What the reader will gain

HIV inhibition can be achieved by transfection of chemically or enzymatically synthesized siRNAs or by DNA-based vector systems to express short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that are processed intracellularly into siRNA. This review compares the merits and shortcomings of the two approaches, focusing on technical and safety issues that will guide the choice of the appropriate strategy for clinical use.

Take home message

Introduction of synthetic siRNA into cells or its stable endogenous production using vector-driven shRNA have both been shown to effectively suppress HIV replication in vitro and in some instances in vivo. Each method has its own advantages and limitations in terms of ease of delivery, duration of silencing, emergence of escape mutants and potential toxicity. Thus, both methods appear to have potential as future therapeutics for HIV, once the technical and safety issues unique to each of the approaches are overcome.

Keywords: antiviral therapy, HIV-1, RNA interference, short hairpin RNA, small interfering RNA

1. Introduction

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the current standard treatment for HIV-1, has dramatically improved the prognosis of HIV-1 infected individuals.1–3 However, alternate therapeutic strategies are being developed due to the high cost, toxicity, patient non-compliance, and resistance associated with life-long HAART regimen. 1, 2, 4–8 Particularly interesting in this regard is the emergence of RNA interference (RNAi) as a potential anti-viral therapeutic. The potency, specificity, and versatility of RNAi-mediated post-transcriptional gene silencing for suppression of acute as well as chronic viral infections including influenza, SARS, flaviviruses, HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been clearly demonstrated in model systems. 9, 10

RNA interference (RNAi) is a phenomenon where small double-stranded RNA (dsRNAs) regulates specific gene expression. The biology and mechanism of RNAi have been extensively reviewed.11–13 Essentially, RNAi can be induced either by endogenously encoded small RNAs called microRNAs (miRNAs) or exogenously introduced small interfering RNAs (siRNAs).

In either case, the 21–23 nucleotide dsRNA associates in the cytoplasm with a protein complex called the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC), whereupon one of the two RNA strands (passenger strand) is degraded and the other “guide” strand guides the RISC to mediate sequence-specific degradation of the corresponding mRNA (in case of siRNAs and shRNAs) and/or translational repression by binding to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) (in the case of miRNAs). The main purpose of RNAi machinery in mammalian cells appears to be to generate small non-coding regulatory miRNAs. However, the existence of RNAi machinery also makes it possible for exotic designer small RNAs [synthetic siRNA or small hairpin RNA (shRNA)] to be used for silencing virtually any gene of interest in a sequence-specific manner. Ever since externally introduced double-stranded siRNAs were shown to silence specific gene expression in mammalian cells, there has been a tremendous interest applying them as potential novel drugs for the treatment of diseases.13

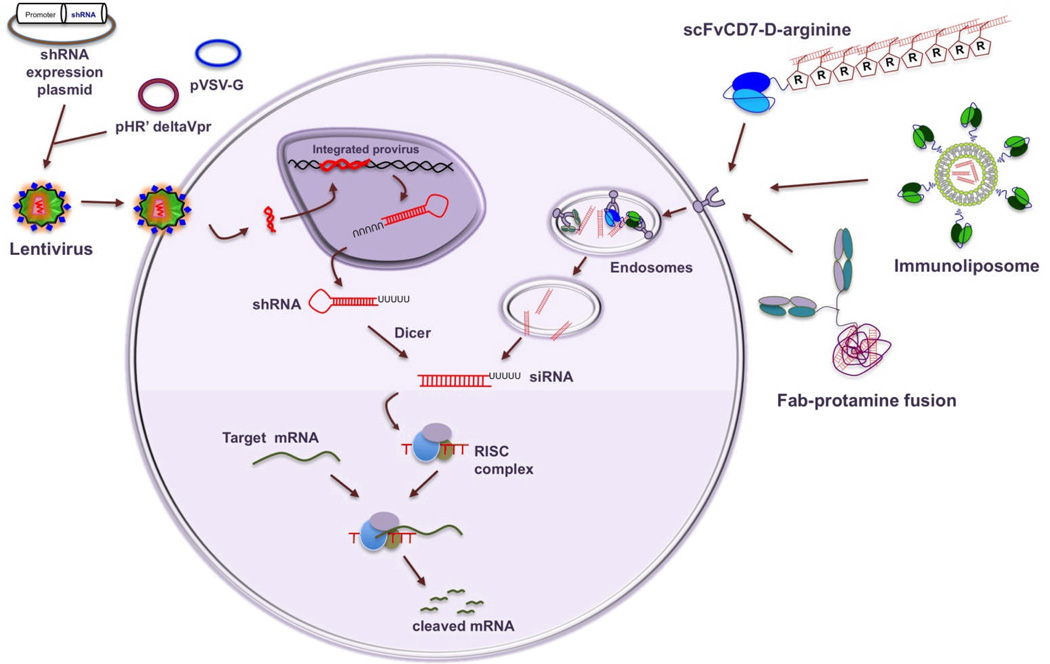

For specific gene silencing, RNAi can be induced by the introduction of chemically or enzymatically synthesized double-stranded siRNA or by intracellular generation of siRNA from vector driven precursor small hairpin (sh) RNAs. In the latter method, an oligonucleotide containing the siRNA sequence followed by a ~9 nt loop and a reverse complement of the siRNA sequence is cloned in plasmid or viral vectors to endogenously express shRNA which is exported out of the nucleus by exportin 514, and is subsequently processed in the cytoplasm by Dicer into siRNA15 in association with dsRNA binding proteins like TRBP and PACT 16. Due to the ease of delivery, particularly in primary cells, non-replicating, recombinant viral vectors (such as adeno, retro and lentiviral vectors) are commonly used for shRNA expression (Fig. 1). Because shRNA is continually produced within the cell, the gene silencing is long lasting (weeks to months). In contrast, synthetic siRNA effects are short lived (generally ~3–5 days) because of dilution with cell division and intracellular degradation. Also, synthetic siRNAs are not generally taken up by cells because of their relatively large size and net negative charge and thus, introduction of siRNA into cells requires the use of some form of delivery reagent (Fig.1).

Figure 1. Promising strategies for using si/shRNA for HIV infection.

The most favored method for expressing shRNA is infection with self inactivating lentiviral particles (generated using transfection with a three-plasmid system (shRNA expression cassette, packaging construct and an envelope construct). After infection, the shRNA expression cassette integrates in the cell’s genome leading to long-term production of shRNA that is processed in the cytoplasm into siRNA. The most promising targeted siRNA delivery strategy consists of a targeting and a cargo moiety. Examples include gp120 Fab-protamine, CD7ScFv-9R protein and siRNA-encapsulated immunoliposome coated with LFA-1 antibody. After delivery, the targeting complex is endocytosed and siRNA released from the endosome is taken up by RISC to mediate gene silencing.

RNAi technologies utilizing shRNA and siRNA have distinct advantages and limitations and thus, both strategies have been used to suppress HIV infection. This review will discuss the progress and challenges with both approaches, highlighting intrinsic differences between siRNA and shRNA with respect to delivery, duration of silencing and induction of off-target effects.

2. Viral versus host gene targets

RNAi can be used to silence several viral genes involved in the HIV-1 life cycle, starting with the incoming viral genome to the viral transcripts generated from the integrated provirus. Alternatively, cellular genes that impact multiple stages of the viral life cycle can also serve as potential therapeutic targets because HIV-1 heavily depends on the host cell machinery for entry, replication, egress and even persistence in a latent state.

2.1 Viral targets for RNAi

Several HIV sequences have been targeted by RNAi including the RNA sequences for structural gag and env proteins,17–19 the Pol enzymes,18 the infectivity factors vif and nef,6, 20, 21, the regulatory proteins tat and rev.6, 19, 22–25 as well as the non-translated RNA sequences in the long terminal repeat (LTR) domain.19, 20 An important unresolved issue is whether the presence of siRNA/shRNA can cure the cell of virus by destroying the viral genome before it is reverse-transcribed and integrated into the host genome. Although some studies reported that the amount of integrated provirus was reduced in cells pretreated with siRNA, the preponderant data suggest only a modest reduction in the level of integrated proviral DNA. 23, 25–28 It remains possible that different siRNAs induce different effects but in general, de novo made viral transcripts rather than the incoming genomic RNA appear to be susceptible to RNAi-mediated degradation.

The propensity of HIV-1 to mutate its sequence poses a serious challenge for designing effective antiviral therapeutics based on an exquisitely sequence-specific strategy like RNAi.29–32 HIV-1 can escape siRNA/shRNA-mediated control through single or multiple nucleotide mutations or even by the deletion of the whole region containing the siRNA recognition site.30 Moreover, there is evidence that HIV-1 can undergo nucleotide substitutions that induce alternative RNA folding, thus shielding a previously targeted sequence from being accessed by the siRNA. 31

One strategy to thwart the ability of the virus to evade restriction by RNAi is to target viral sequences that are highly conserved across the various clades and strains.8 RNAi target sequences have been identified in the HIV-1 genomic regions that have essential roles in maintaining structural and functional integrity of the virus.8, 33–35 In fact, a large number of relatively conserved HIV-1 sequences have been identified for potential RNAi targeting.36, 37 In one study, a highly conserved vif target sequence was able to protect CD4 T cells from all the HIV-1 clades, including multiple isolates of clade B, prevalent in the West.8 An even more robust strategy is to simultaneously target multiple discrete and relatively well-conserved sequences. The likelihood that a single viral RNA molecule would mutate all targeted sequences becomes increasingly small as the number of targets is increased.36

2.2 Host gene targets for RNAi

The difficulty in addressing the high rates of viral mutation has led to an emphasis on using cellular targets as candidates for HIV therapeutics with RNAi. With increasing knowledge of HIV biology, targeting relevant cellular genes to clear both circulating and latent viral reservoirs may become possible, which could prove more effective than mere suppression of actively replicating virus by silencing viral genes. RNAi targets that facilitate viral entry are ideal for inducing HIV resistance in susceptible cells as the virus would be unable to initiate the infection.17 Many studies have targeted the viral receptor CD417, 34, 38, and the co-receptors CCR56, 7, 38–40and CXCR438, 41, 42 that are essential for attachment of the HIV-1 particle to the cell and subsequent viral entry. CCR5, a co-receptor for the macrophage-tropic virus that predominates during early infection, holds particular promise as a therapeutic target because a 32-base pair deletion of the gene is known to be relatively well tolerated and at the same time confer resistance to HIV infection.43 The validity of CCR5 as a therapeutic target has received further boost from a recent case study where a HIV seropositive patient transplanted with stem cells from CCR5delta32 homozygous donor remained virus-free without HAART drugs up to 20 months after transplanation.44 Even individuals who are heterozygous for this deletion have delayed progression to AIDS.45–47 However, a potential problem is the ability of HIV-1 to switch tropism to CXCR4 during the course of AIDS, which could create a more virulent infection.48 To circumvent this possibility, dual-specific shRNAs that combine anti-CCR5 and CXCR4 shRNAs have been engineered and down-regulation of these receptors has been shown to virtually shutdown viral infectivity in human lymphocytes.38, 49, 50 However, a cautionary note on targeting the T cell tropic co-receptor CXCR4 is that the molecule may be required for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) homing to marrow and subsequent T cell differentiation.51–53

Many other host factors important for HIV-1 replication have also been successfully targeted for RNAi, including the transcription factor NF-kB, cyclin T1, cyclin- dependent kinase 9, or suppressor of Ty5 homolog, but they may be of limited therapeutic utility because of their important roles in cellular physiology.54–56 With increasing knowledge of HIV-host cell interaction through recent advances in high throughput genomic and proteomic screens and bioinformatics prediction, the repertoire of potential host RNAi targets for inhibiting HIV replication is rapidly expanding. Three independent studies have used the power of RNAi itself for identifying novel host cell genes linked to HIV replication.57–59 Although the results from these and multiple other genome wide screens have been highly divergent with respect to the host genes identified (possibly because of differences in the target cells used for infection and the varying sampling times), nevertheless the data sets do show overlap for some of the identified genes.57–59 Particularly interesting from a therapeutic standpoint are the retrograde golgi transport proteins Rab-6 and Vps53. siRNA knockdown of either of these proteins was sufficient to block HIV replication at a very early step, even before reverse transcription of the viral genome, with no deleterious effect on the cell viability.58 Importantly, Rab-6 knockdown efficiently suppressed both R5 and R4 tropic viruses, suggesting that it could provide a better target than the co-receptor CCR5. Similarly, knockdown of the cellular transportin 3 (TNPO3) blocked HIV at the next stage after reverse transcription but before integration of the viral genome.58 If these and other putative HIV-dependency factors can be verified as relevant for infection of primary cells and their ablation is well tolerated, they would provide a major cache of potential therapeutic RNAi targets for treating HIV infection.

A novel possibility for intervention has recently emerged based on the knowledge about the role of cellular miRNA machinery in maintaining HIV in a productive or latent state. Certain cellular miRNAs, in particular miR-28, miR-125b, miR-150, miR-223 and miR-382 have been reported to significantly contribute to the maintenance of viral latency.46 In fact, neutralization of these miRNAs using antagomirs was enough to induce virus production from latently infected CD4 T cells, opening up the possibility of manipulating select cellular miRNAs for reversing viral persistence.

Given the special challenges posed by the HIV life cycle and genetic variability, use of a combination of siRNAs/shRNAs targeting conserved viral sequences and nonessential host genes important in the viral life cycle may be the optimal strategy to inhibit HIV at several stages of its life cycle. For HIV gene therapy, the emerging consensus is to combine RNAi with other HIV inhibitory approaches such as ribozymes, RNA decoys, transdominant proteins, species-specific restriction factors like TRIM5alpha, antisense RNA and aptamers to further safeguard against viral escape akin to antiretroviral drug cocktails. 3, 60–62 In fact, a clinical trial is underway with a triple combination lentiviral construct comprised of a TAR RNA decoy, shRNAs targeted to tat and rev open reading frames and a chimeric anti-CCR5 trans-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme.3

3. Synthetic siRNA for HIV inhibition

Advances in understanding the RNAi pathway has led to substantial improvements in rational design of siRNAs for potential use as a drug for treating diseases. From an understanding of the thermodynamic features of siRNA loading in RISC, it has become clear that the duplex should be designed so that the antisense guide strand is less stable at its 5' end thereby favoring its uptake by RISC. Another novel design feature is the use of longer duplex RNA with a 2 nt 3’ overhang only at the antisense end in place of the short 19–21 nt siRNA.63 The longer form has been demonstrated to trigger more potent gene silencing because it acts as a dicer substrate and the dicer cleaved product allows more efficient RISC loading.64, 65

Despite the rapid advances and great promise, developing siRNA as an antiviral drug for HIV-1 remains a challenge. Delivery is a major hurdle as mammalian cells and tissues do not spontaneously take up negatively charged molecules like siRNA.66–68 The susceptibility of siRNA to endogenous nuclease is also an impediment but can be overcome by introducing chemical modifications in the siRNA or by binding to or encapsulation of siRNA within the delivery reagent. Thus, therapeutic success will hinge on developing practical delivery reagents that are capable of protecting siRNA in circulation as well as of delivering it to the cytoplasm of appropriate cell types in vivo.6

A number of non-viral carriers have been tested for potential in vivo delivery of siRNA including cationic polymers, peptides or liposomes and lipid-like materials that form complexes with negatively charged siRNAs by ionic interactions.69–70 The resulting complexes not only allow cellular uptake of siRNA via the endocytic pathway but also provide excellent protection from nuclease attack. For example cationic PEGylated liposomes called ‘stable nucleic acid lipid particles’ (SNALPs) have been used to deliver siRNA to the liver in cynomologous monkeys to reduce serum cholesterol and LDL levels.71 A significant development is the use of siRNA carriers that display various ligands (e.g. antibodies, peptides, and sugar chains) that bind to specific cell surface proteins.6, 70 One study used a fusion protein of the Fab fragment of antibody against HIV gp160 with the positively charged protamine that enables siRNA binding.72 This reagent effectively delivered siRNA to HIV-infected cell lines and primary T cells in vitro. Moreover, systemic treatment in mice resulted in cell-specific targeting to HIV envelope-expressing melanoma cells. This initial demonstration of the feasibility of selective delivery to HIV-infected cells was followed by a more generally applicable technique of targeting specific cell-surface proteins of immune cells. A single chain antibody variable fragment (scFv) to the CD7 receptor conjugated to a nucleic acid binding nonamer arginine peptide (9R) was successfully used for T cell-specific delivery of antiviral siRNA.6 In this study, it was possible to suppress HIV-1 replication and prevent CD4+ T cell depletion in vivo in humanized NOD/SCIDIL2rγ −/− mice {reconstituted with human lymphocytes (Hu-PBL) or CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (Hu-HSC)} by simple intravenous injections of a combination of siRNAs targeting the viral vif and tat genes along with the host CCR5 gene. Importantly, CD7 mediated delivery of siRNA successfully silenced the target gene in naive/resting T cells6 that are vulnerable to infection when they become activated and also serve as latent reservoir that can rekindle viral replication after interruption of HAART. The CD7-specific antibody is well suited for siRNA delivery because CD7 is expressed by most T cells and is rapidly internalized after binding of the antibody-siRNA complexes.6 Moreover, this antibody has already been used in clinical studies to target toxins to T cell lymphomas and leukemias.66 Another antibody directed to a predominant integrin on human leukocytes, LFA-1 was also shown to deliver siRNA to immune cells when expressed as an antibody-protamine fusion protein.73 Although the antiviral efficacy in vivo remains to be tested, an advantage over CD7 scFv, which selectively targets T cells is that the LFA-1 antibody would permit siRNA delivery to a broader spectrum of HIV susceptible cell types, including T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells that play key roles in infection and pathogenesis.73 In fact, in a recent study, a nanoparticle formulation coated with this LFA-1 antibody (LFA-1 tsNPs) was able to efficiently deliver anti-HIV siRNAs to T cells and macrophages in vivo and reduce plasma viral load and CD4 T cell loss in the humanized mouse model. 74

For any antibody-based delivery reagent, the prospect of repeated in vivo administration brings in the risk of triggering immune response to the antibody itself. For instance, in a nonhuman primate model, reinjection of human transferrin conjugated polymers elicited antibodies to transferrin.75 Perhaps fully or partially optimized humanized antibodies can be used to reduce potential immunogenicity of targeting moieties.76 The antibody amounts could also be reduced by use of delivery vehicles like tsNPs for in this case, unlike methods where siRNA binding is through positively charged residues linked to the antibody, the antibody only serves as a targeting ligand and thus large payloads of siRNA can be packaged without the need to increase the antibody levels on the surface of the nanoparticle.

A novel non antibody-based delivery vehicle in which the protein transducing domain (PTD) from the HIV TAT protein is attached to a double-stranded RNA-binding domain (DRBD) that binds siRNA with high avidity was also shown to efficiently deliver siRNA to T cells in vivo.77 However, the PTD-DRBD-delivered system is not selective to T cells as it can induce RNAi in many different primary and transformed cell types. This could be a disadvantage in that targeted delivery restricted to the relevant cell types improves the therapeutic availability of siRNA in vivo thereby reducing the siRNA dose needed. This might also be important to minimize the risk of undesired potential of off-target effects in non-targeted bystander cells.66, 78

4. shRNA for HIV inhibition

On a parallel track with the development siRNA-based technologies for HIV inhibition, shRNA-expressing DNA vectors have also been developed for potential long-term suppression of the virus. Viral vectors like adenovirus (AdV), adeno-associated virus (AAV), and retroviruses like oncoretrovirus and lentivirus (LV) are generally used for shRNA expression (reviewed in 79, 80). Lentiviruses are particularly suited for gene therapy because they integrate into the host genome to provide life-long expression of the shRNA transgene. Another advantage of lentiviruses is that they can deliver large genetic payloads, a property that can be exploited for expressing multiple shRNAs simultaneously.36 Although oncoretroviruses are also capable of integration into the host genome, they depend upon nuclear membrane breakdown during cell division to transduce cells, whereas lentiviruses can transduce quiescent cells as they use their own active nuclear import pathway for integration.81, 82 Lentiviruses, like oncoretroviruses (e.g., MLV based vectors), have been rendered progressively safer by the development of split plasmid systems for vector production to prevent generation of replication competent virus (reviewed in80, 83). The basic idea here is to generate a virus that after a single round of infection ensures stable integration of the transgene with only a minimal component of the viral genome, so that the transgene is continually expressed but infectious virus is not generated. 84 This system also avoids HIV envelope and instead uses a substitute envelope for pseudotyping lentiviral particles, which also serves to broaden the tropism of the vector. Most commonly used for this purpose is the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G), which is resistant to ultracentrifugation and freeze-thaw cycles and that can enter the host cell via the endocytic pathway thereby reducing the requirements of HIV accessory proteins for infectivity.85

Lentiviral pseudotyping methods that allow targeted delivery to HIV susceptible cells are also being developed to improve transduction efficiency and to facilitate direct administration into the bloodstream. One approach has used lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with retroviral envelope proteins fused to targeting molecules, such as single-chain antibodies or cytokines. 86, 87 In another approach, the Fc-binding region of protein A (ZZ domain) has been inserted into the original receptor-binding region of the Sindbis virus envelope protein used for lentiviral pseudotyping. 88 The zz domain serves as a versatile adapter molecule as any cell targeting antibody can be bound through the interaction with the Fc region of antibodies. This approach has been applied for generating a lentiviral vector tagged with CCR5-directed monoclonal antibody. This reagent was shown to transduce a CCR5 shRNA into HIV-susceptible cells and confer resistance to HIV-1 infection. 89 More recently, a biotin adaptor peptide has also been similarly inserted into the same site in the Sindbis envelope protein to permit high affinity binding of the biotinylated vector to avidin-antibody fusion proteins, which may provide a more stable reagent for in vivo targeting.90

The possibility of targeting its own sequence which is always a part of the vector genome is a theoretical disadvantage with shRNA expressed from a lentiviral vector but studies show that such self targeting does not actually occur. 91 On the other hand, shRNAs sequences that target the viral Gag-Pol region can affect the generation of the transducing lentivirus by targeting the Gag-Pol genes that are provided in trans for packaging the lentiviral vector. However, the problem can be circumvented with the use of human codon-optimized gag-pol gene in the packaging construct to avoid reducing transducing viral titers while retaining gene silencing activity in the context of HIV-1 infection. 92

4.1. shRNA design

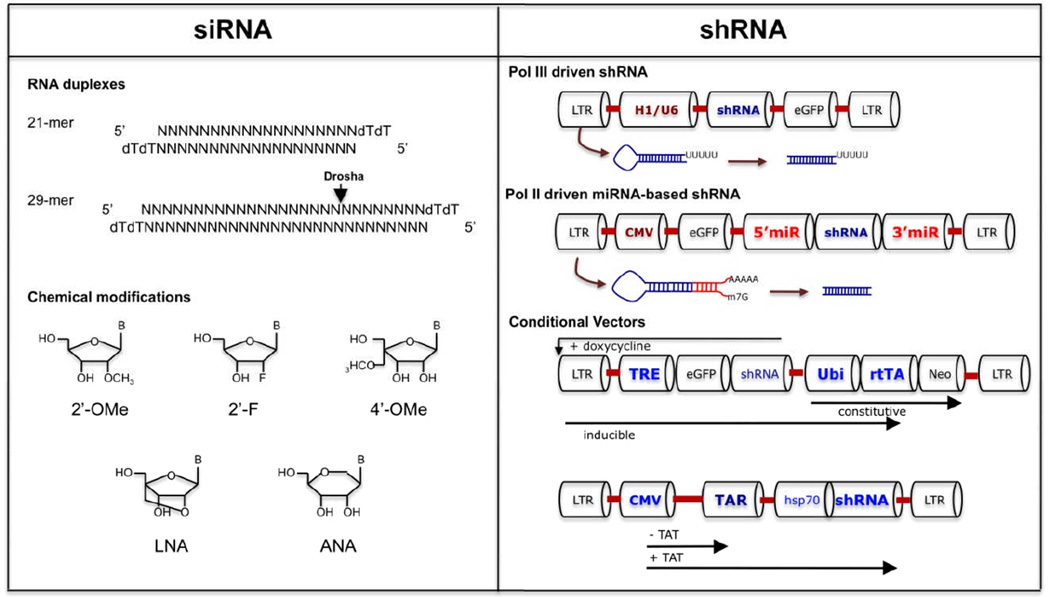

In its earliest form, vectors for endogenous siRNA generation were engineered to express templates for precursor short hairpin RNA (shRNA) that consist of a sequence of 21–29 nt, a short loop region, and the reverse complement of the sequence and a short terminator (5–6 T residues) sequence. Because the expressed RNA is short, generally Pol III promoters such as U6 or H1 were used (Figure. 2). These promoters are strong and generate large amounts of transcription products (although H1 promoter is weaker than U6) that serve as substrates for Dicer. On the downside, over expression of U6 driven shRNA could be toxic presumably due to interference with cellular miRNA expression. 93, 94

Figure 2. si/shRNA design to enhance potency and reduce toxicity.

Short and long siRNA triggers and chemical modifications of siRNA are depicted on the left. Strategies for conventional shRNA, shRNAmiRs and conditional shRNA expression are depicted on the right

Recently miRNA-based lentiviral vectors have been used for expressing shRNAs. shRNA embedded in microRNA scaffold provide more robust expression of siRNAs and gene silencing as compared to conventional shRNA constructs.95 Pol II driven polycistronic transcripts containing multiple shRNA sequences can be efficiently expressed from the miRNA backbone. This is a major advantage in treatment of HIV infection as expression of a single sh/siRNA can lead to the emergence of escape mutants.31 In two recent studies simultaneous expression of multiple anti-viral shRNAs from the six pre-miRNA-encoding mir-17–92 cluster or a polycistronic miR-106b cluster (miR-106b, miR-93, miR-25) had better anti-HIV efficacy than individual shRNAs.96, 97 miR-30 and mir-155-based artificial vectors have also been used for expression of antiviral shRNAs. In one study expression of anti-HIV shRNA from a mir-155-based vector demonstrated robust and sustained gene expression for over four weeks.98 These features are a big plus for in vivo application of mir-based shRNA vectors. Another positive conclusion from these studies is that template sequences inserted in a miRNA backbone are less likely to compete with the endogenous miRNAs for transport and incorporation into the RISC complex. Moreover, unlike conventional shRNA constructs that rely on the integration of multiple copies in the host genome, miR-based shRNA can knockdown gene expression efficiently even at a single copy integration.99 Induction of innate antiviral responses is also reduced with the use of shRNAmiRs, probably because with assimilation into the miRNA pathway the shRNA generation occurs by the natural Drosha and Dicer processing.100

4.2 Conditional shRNA vectors

Inducible expression of transgenes provides an improved level of safety as it avoids much of the unintended consequences of viral vector-mediated delivery and gene silencing. Reversible conditional vectors are usually drug-inducible (e.g. tetracycline) and can be expressed from a pol III or pol II promoters. Repression can be achieved by steric hindrance, as with tetracycline binding to the Tet repressor (tetR) thereby sequestering off the Tet operator (tetO), or by transactivation which relies on the expression of a engineered pol III transactivator (tTA or rtTA), which in turn induces transcription of shRNA from a modified U6 promoter.101 In another elegant approach, anti-HIV rev shRNA was cloned under a pol II hsp70 promoter that could be transactivated by HIV-1 TAT, downstream of an LTR sequence.102 In the absence of TAT, transcription from the LTR was stalled at the TAR sequence in the LTR and no shRNA was made. However upon TAT induction, it was able to bind the TAR element and relieve the transcriptional block by recruiting RNA polymerase to initiate shRNA expression.102 The main advantage of this system is that the shRNA expression is only induced in HIV-1 infected cells, thus avoiding non-specific toxic effects.

Proof of concept studies in humanized immunodeficient mouse models have shown that CD34+ HSC’s transduced with lentiviral shRNA can differentiate into monocytes and/or T cells.103–105 However, in these studies HIV inhibition has only been validated ex vivo using T cells and macrophages differentiated within xenografts transplanted with human CD34+ HSC. In a study that augurs well for human gene therapy for HIV, the Chen group has demonstrated that the strategy also works in a rhesus macaque hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell transplant model that more closely mimics humans.106 In two animals reconstituted with CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells transduced with H1 promoter-driven shRNA targeting CCR5, about 5% of progeny lymphocytes were shown to express the transgene for up to 14 months. Another encouraging feature was the lack of vector or promoter related toxicity during this period of observation despite the use of a potent shRNA that consistently downmodulated gene expression. However, as in the mouse model, resistance to simian immunodeficiency virus infection was only demonstrated ex vivo. Thus, realizing the full promise of RNAi gene therapy may require further refinements to achieve gene marking levels that permit direct virus challenge in vivo. More rigorous studies in preclinical models would also be required to validate the approaches and satsfactorily allay the concerns of vector toxicity, insertional mutagenesis, as well as the possibility of emergence of replication competent viruses.

5. Toxicity and bio-safety

Better understanding of mechanisms that lead to toxicity and bio-safety issues are essential before RNAi can become a practical therapeutic. Important aspects related to toxicity that needs consideration include immune activation and off-target effects.

Immunostimulation by RNA-based gene therapy is a potential concern as intracellular presence of dsRNA can activate components of the innate arm of the immune system like cytosolic dsRNA-activated protein kinase PKR and retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG-I) systems that lead to a type I interferon (IFN) response and further activation of IFN-regulated genes.107, 108 For exogenously introduced siRNAs, the induction of innate immunity is dependent on the siRNA structure and sequence, method of delivery, and cell type. In particular, immuno-stimulatory sequences that contain 5'-UGUGU-3' or 5'-GUCCUUCAA-3' have been shown to interact with different endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs) leading to signaling cascade that elicits an IFNα production in dendritic cells109. In some cases the delivery vehicles used for inducing siRNA uptake by cells can themselves induce an inflammatory response.110 Similarly, shRNA, expressed from the pol III promoters generally have a triphosphate at their 5’ ends that can activate RIG-I to induce an interferon response, resulting in the activation of PKR and subsequent shut down of cellular translation.107, 108

Both siRNA and shRNA can induce off-target effects by fortuitous base pairing with unintended mRNAs resulting in suppression of important cellular components. 111–113 Complementarity with 2–7 nucleotides at the 5’ end of the guide or passenger strand has been shown to be a key determinant in directing off-target effects.111 Off-target effects can be reduced by avoiding the incorporation of sense strand of siRNA into the RISC complex. Chemical modifications that include 5’ methyl or 2′-O-methyl ribosyl substitution at position 2 in the guide strand can effectively avoid sense strand-RISC formation and reduce off-target silencing.114–117 Also incorporation of two nucleotide overhangs at the 3’ end of only the antisense strand can reduce off-target sequences by favoring its preferential incorporation to RISC.118 Additionally, use of software such as Smith Waterman and dsCheck,119, 120 for alignment analysis of short sequences may further avoid induction of off-target miRNA-like effects by the selected siRNA sequences. The advantage with synthetic siRNA over shRNA is that it not only permits specific chemical modifications to reduce off-target effects but also provides the flexibility to quickly modify the sequence if it negatively affects the potency of gene suppression.

Since the RNAi pathway shares the cellular endogenous miRNA machinery, with both siRNA and shRNA, there is an opportunity for competition with miRNAs for loading to the RISC.121 Because miRNAs are essential for the regulation of mammalian cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis, if the machinery for miRNA biogenesis is diverted to handle exogenous siRNA or shRNA, then a dearth of miRNAs can potentially manifest as toxicity.122, 123 In mice, severe liver toxicity and fatality were reported within 2 weeks of shRNA treatment which could be attributed to the saturation of the miRNA pathway by over-expressed shRNA.124 The problem may be more easily overcome with synthetic siRNA where the dose administered can be controlled. In the case of vector encoded shRNA, the problem will have to be overcome by the use of weaker promoters to generate potentshRNAs that work at low concentrations or by expressing shRNA from miR-based vectors that assimilate more seamlessly into the endogenous pathway. In a preclinical study in the rhesus macaque model, a potent shRNA sequence directed at CCR5 was found to be highly effective and nontoxic when expressed from the H1 Pol III promoter in place of the much stronger U6 promoter.104

For clinical use of lentiviral vector for shRNA expression, insertional mutagenesis is a potential hazard to be considered. In this respect, lentiviral vectors are considered much more safer than gammaretroviral vectors as they have less predilection for integration into transcriptionally active sites. However, in a recent study that compared the transformation capability of the two vectors in a sensitive assay system, a SIN lentiviral vector was also shown to be capable of triggering transformation of primary hematopoietic cells although at a much lower frequency than a SIN gammaretroviral vector. A common insertion site (CIS) in the first intron of the Evi1 proto-oncogene could be identified in the lentiviral vector-transformed mutants 125. On a more optimistic note, the study also noted that the mutagenic capability of the vector could be reversed by altering its enhancer–promoter elements.

Conclusions and Perspective (Expert opinion)

Synthetic siRNA or vector-based shRNA?

In cultured cells, HIV inhibition has been effectively achieved with both siRNA or vector expressed shRNA approaches. However, tailoring RNAi-based intervention for a complex virus like HIV that is able to adapt so cleverly to drugs and immune pressure presents formidable challenges. Both the transient siRNA and stable shRNA approaches have their unique advantages and disadvantages with respect to duration of gene silencing, toxicity and delivery efficiency (Table. 1), which will have to be considered carefully for use of RNAi as therapy.

Table 1.

Synthetic siRNA versus vector-based shRNA for HIV therapy

| siRNA | shRNA | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of knockdown | Transient (days) | Stable (months to years) |

| Chemical modification | Can be altered to increase stability and specificity | Natural, limited |

| Cloning/construction | Not required | Required |

| Production throughput | Fast | Slow |

| Targeting multiple sequences | Easy | Possible but slow/expensive |

| Combination Therapy | Few options | Can be combined with other anti-HIV gene therapy approaches. |

| Delivery formulation | Special carriers required for in vivo delivery to hard to transfect primary T cells and macrophages | CD34+ HSCs or primary T cells have to be transduced ex vivo with gene therapy vectors. |

| In vivo gene marking | Good with appropriate delivery strategy | Poor but proportion of gene marked cells would increase due to selective advantage during infection |

| HIV inhibition in vivo | Good in humanized mice | Not tested in animal models. Clinical trial underway. |

| Toxicity | Off target effects, interferon induction and immune response to delivery vehicle | Off target effects, interferon induction and insertional mutagenesis |

| Generation of replication competent virus | Not applicable | Potential hazard |

| Long term safety | Controllable | Uncontrollable |

Long-term endogenous expression of siRNA from vector-derived shRNA is probably the most optimal strategy for a persistent infection like HIV. The major advantage being the possibility of achieving durable viral suppression without the repeated administrations required with exogenously introduced siRNA. Further, although synthetic siRNA can be loaded onto RISC for RNAi function, the loading process is generally less efficient than shRNA that is processed by the endogenous RNAi machinery.126,64

As HIV pathogenesis is primarily driven by depletion of CD4+ T cells, one possible practical form of shRNA therapy is to infuse an in vitro expanded population of autologous T cells that are genetically modified to express antiviral shRNAs. In a recent study, infusion of CD4+ T cells transduced with lentivirus expressing an antisense oligonucleotide against the HIV-1 envelope gene was tested in humans with no adverse effects and up to 4% of CD4+ cells expressing the transgene.127 However, although there may be short-term benefit with this form of therapy, transfused T cells decline over time and repeated infusions could adversely affect the natural T cell repertoire. A more optimal gene therapy option would be to transduce hematopoietic stem cells so that the DNA precursor for the shRNA becomes a permanent part of their genome and their progeny cells. As the gene modified HSCs would be capable of self-renewal, theoretically they could serve as a life-long source of HIV resistant multiple cell lineages (including T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells). Lentiviral vectors are well suited for HIV gene therapy as they have the ability to efficiently transduce primary T cells and quiescent stem cells. However technical aspects of lentiviral gene therapy need more refinement. At the current stage of development, resting T cells are far less amenable to transduction than activated cells. Even HSCs can be transduced efficiently only after ex vivo culture in a cytokine cocktail that is likely to compromise pluripotency, leading to inefficient generation of gene marked progeny blood cells. Variable gene expression during in vitro differentiation can further compound the problem.128 Strategies such as using insulators (like cHS4 element, sea urchin Ars) that resist DNA methylation or replacement of U3 region of the viral LTR with a DNAse hypersenstitive HS2 enhancer element region from the erythroid GATA-1 transcription factor gene are being tested to reduce epigenetic silencing without loss of viral titer, gene expression, and genomic stability in HSCs.129–131

If the delivery hurdle can be overcome, despite the transient nature of gene silencing, synthetic siRNA as a drug offers several obvious advantages over vector-driven endogenous expression. The simplicity of design, manufacturing, and testing, combined with the ability to stop the drug in case of any toxic effects, make it potentially easier and safer to use than vector-based shRNA therapy. Additionally, studies in preclinical HIV models suggest that with the use of a suitable delivery vehicle, siRNA uptake can be induced in a large proportion of vulnerable cells.6, 70 It is doubtful if such level of gene marking can be achieved with a shRNA gene therapy approach. Another significant benefit of siRNA over shRNA is the short time required for target screening. In the context of HIV-1, the ability to quickly change siRNA sequences to keep pace with the mutating virus would be an important advantage. The inherent flexibility in changing siRNA combinations would also allow testing multiple combinations of siRNAs. In addition to viral gene targets, many host molecules that play an important role in HIV-1 life cycle58 can be transiently perturbed to delay primary infection or curb viral dissemination or even reverse latency by use of antagonists to cellular microRNA that modulate HIV gene expression.132

Synthetic siRNA also offers the exciting possibility of application as a microbicide for protection against HIV at the port of entry. Local vaginal delivery of synthetic siRNA has been demonstrated to protect mice from lethal herpes simplex virus challenge.133, 134 The level of difficulty is likely to be higher for using the strategy for HIV infection as unlike HSV-2, where resident epithelial cells have to be protected, in the case of HIV, delivery of siRNA will have to be accomplished across the epithelial barrier into populations of immune cells that are resistant to nucleic acid uptake. Moreover, because of their constant influx and egress, hematopoietic cells that initiate HIV infection at the site may be more “hard to hit” targets.

Conclusions

Both shRNA and siRNA are strong contenders as potential treatment options for HIV infection. Taking into consideration the unique advantage that each of the platform has to offer, it may be wise to explore both strategies in parallel. With further advances, it may even become possible to combine the two approaches so that gene-modified CD34+ HSCs are used to ensure long term generation of HIV resistant cells whereas “siRNA drugs” are used in the interim or for transient silencing of additional host genes whose long-term ablation is poorly tolerated. So far the preclinical studies in mouse and rhesus macaques and more recently the clinical studies in humans have not yielded any unprecedented toxicity or side effects that preclude the use of siRNA delivery platforms or shRNA vectors for treating HIV. Results of the ongoing clinical trial with vector-based shRNA and others to come will determine whether RNAi-based therapeutics can become an active player in the treatment of HIV infection. In conclusion, the exciting advances reviewed here provide great optimism for future applications of both siRNA- and shRNA-based RNAi therapies for HIV.

Highlights.

Viral and cellular gene targets

Vehicles for delivery of anti-viral synthetic siRNAs

Lentiviral therapy to generate HIV-resistant T cells and macrophages

Generation of multiplexed anti-viral shRNA from miRNA-based vectors

Toxicity and biosafety issues for si/shRNA

Scope of siRNA and shRNA for anti-HIV therapy

References

- 1.Rossi JJ, June CH, Kohn DB. Genetic therapies against HIV. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Dec;25(12):1444–1454. doi: 10.1038/nbt1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherer L, Rossi JJ, Weinberg MS. Progress and prospects: RNA-based therapies for treatment of HIV infection. Gene Ther. 2007 Jul;14(14):1057–1064. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson J, Li MJ, Palmer B, Remling L, Li S, Yam P, et al. Safety and efficacy of a lentiviral vector containing three anti-HIV genes--CCR5 ribozyme, tat-rev siRNA, and TAR decoy--in SCID-hu mouse-derived T cells. Mol Ther. 2007 Jun;15(6):1182–1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manjunath N, Kumar P, Lee SK, Shankar P. Interfering antiviral immunity: application, subversion, hope? Trends Immunol. 2006 Jul;27(7):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar P, Manjunath N, Lieberman J. The prospect of silencing disease using RNA interference. JAMA. 2005 Mar 16;293(11):1367–1373. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar P, Ban HS, Kim SS, Wu H, Pearson T, Greiner DL, et al. T cell-specific siRNA delivery suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Cell. 2008 Aug 22;134(4):577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song E, Lee SK, Dykxhoorn DM, Novina C, Zhang D, Crawford K, et al. Sustained small interfering RNA-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibition in primary macrophages. J Virol. 2003 Jul;77(13):7174–7181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7174-7181.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SK, Dykxhoorn DM, Kumar P, Ranjbar S, Song E, Maliszewski LE, et al. Lentiviral delivery of short hairpin RNAs protects CD4 T cells from multiple clades and primary isolates of HIV. Blood. 2005 Aug 1;106(3):818–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh SK. RNA interference and its therapeutic potential against HIV infection. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008 Apr;8(4):449–461. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang DD. The potential of RNA interference-based therapies for viral infections. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008 Feb;5(1):33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dykxhoorn DM, Lieberman J. The silent revolution: RNA interference as basic biology, research tool, and therapeutic. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haasnoot J, Westerhout EM, Berkhout B. RNA interference against viruses: strike and counterstrike. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Dec;25(12):1435–1443. doi: 10.1038/nbt1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interference-based therapeutics. Nature. 2009 Jan 22;457(7228):426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003 Dec 15;17(24):3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000 Mar 16;404(6775):293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tijsterman M, Plasterk RH. Dicers at RISC; the mechanism of RNAi. Cell. 2004 Apr 2;117(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novina CD, Murray MF, Dykxhoorn DM, Beresford PJ, Riess J, Lee SK, et al. siRNA-directed inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 2002 Jul;8(7):681–686. doi: 10.1038/nm725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu JY, DeRuiter SL, Turner DL. RNA interference by expression of short-interfering RNAs and hairpin RNAs in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Apr 30;99(9):6047–6052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092143499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capodici J, Kariko K, Weissman D. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by small interfering RNA-mediated RNA interference. J Immunol. 2002 Nov 1;169(9):5196–5201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacque JM, Triques K, Stevenson M. Modulation of HIV-1 replication by RNA interference. Nature. 2002 Jul 25;418(6896):435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature00896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto T, Miyoshi H, Yamamoto N, Inoue J, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y. Lentivirus vectors expressing short hairpin RNAs against the U3-overlapping region of HIV nef inhibit HIV replication and infectivity in primary macrophages. Blood. 2006 Nov 15;108(10):3305–3312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee NS, Dohjima T, Bauer G, Li H, Li MJ, Ehsani A, et al. Expression of small interfering RNAs targeted against HIV-1 rev transcripts in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002 May;20(5):500–505. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coburn GA, Cullen BR. Potent and specific inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by RNA interference. J Virol. 2002 Sep;76(18):9225–9231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9225-9231.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boden D, Pusch O, Ramratnam B. HIV-1-specific RNA interference. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2004 Aug;6(4):373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surabhi RM, Gaynor RB. RNA interference directed against viral and cellular targets inhibits human immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 replication. J Virol. 2002 Dec;76(24):12963–12973. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12963-12973.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu WY, Myers CP, Kilzer JM, Pfaff SL, Bushman FD. Inhibition of retroviral pathogenesis by RNA interference. Curr Biol. 2002 Aug 6;12(15):1301–1311. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ter Brake O, t Hooft K, Liu YP, Centlivre M, von Eije KJ, Berkhout B. Lentiviral vector design for multiple shRNA expression and durable HIV-1 inhibition. Mol Ther. 2008 Mar;16(3):557–564. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Eije KJ, ter Brake O, Berkhout B. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape is restricted when conserved genome sequences are targeted by RNA interference. J Virol. 2008 Mar;82(6):2895–2903. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02035-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boden D, Pusch O, Lee F, Tucker L, Ramratnam B. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape from RNA interference. J Virol. 2003 Nov;77(21):11531–1155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11531-11535.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das AT, Brummelkamp TR, Westerhout EM, Vink M, Madiredjo M, Bernards R, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escapes from RNA interference-mediated inhibition. J Virol. 2004 Mar;78(5):2601–2665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2601-2605.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westerhout EM, Ooms M, Vink M, Das AT, Berkhout B. HIV-1 can escape from RNA interference by evolving an alternative structure in its RNA genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):796–804. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabariegos R, Gimenez-Barcons M, Tapia N, Clotet B, Martinez MA. Sequence homology required by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to escape from short interfering RNAs. J Virol. 2006 Jan;80(2):571–577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.571-577.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang LJ, Liu X, He J. Lentiviral siRNAs targeting multiple highly conserved RNA sequences of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Gene Therapy. 2005 Jul;12(14):1133–1144. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han WL, Wind-Rotolo M, Kirkman RL, Morrow CD. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by siRNA targeted to the highly conserved primer binding site. Virology. 2004 Dec 5;330(1):221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dave RS, Pomerantz RJ. Antiviral effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific small interfering RNAs against targets conserved in select neurotropic viral strains. J Virol. 2004 Dec;78(24):13687–13696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13687-13696.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ter Brake O, Konstantinova P, Ceylan M, Berkhout B. Silencing of HIV-1 with RNA interference: a multiple shRNA approach. Mol Ther. 2006 Dec;14(6):883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naito Y, Nohtomi K, Onogi T, Uenishi R, Ui-Tei K, Saigo K, et al. Optimal design and validation of antiviral siRNA for targeting HIV-1. Retrovirology. 2007;4:80. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson J, Banerjea A, Akkina R. Bispecific short hairpin siRNA constructs targeted to CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 confer HIV-1 resistance. Oligonucleotides. 2003;13(5):303–312. doi: 10.1089/154545703322616989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjea A, Li MJ, Bauer G, Remling L, Lee NS, Rossi J, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 by lentiviral vector-transduced siRNAs in T lymphocytes differentiated in SCID-hu mice and CD34+ progenitor cell-derived macrophages. Mol Ther. 2003 Jul;8(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin XF, An DS, Chen IS, Baltimore D. Inhibiting HIV-1 infection in human T cells by lentiviral-mediated delivery of small interfering RNA against CCR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jan 7;100(1):183–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson J, Banerjea A, Planelles V, Akkina R. Potent suppression of HIV type 1 infection by a short hairpin anti-CXCR4 siRNA. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003 Aug;19(8):699–706. doi: 10.1089/088922203322280928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou N, Fang J, Mukhtar M, Acheampong E, Pomerantz RJ. Inhibition of HIV-1 fusion with small interfering RNAs targeting the chemokine coreceptor CXCR4. Gene Ther. 2004 Dec;11(23):1703–1712. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Y, Paxton WA, Wolinsky SM, Neumann AU, Zhang L, He T, et al. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996 Nov;2(11):1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Mussig A, Allers K, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 12;360(7):692–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garred P, Eugen-Olsen J, Iversen AK, Benfield TL, Svejgaard A, Hofmann B. Dual effect of CCR5 delta 32 gene deletion in HIV-1-infected patients. Copenhagen AIDS Study Group. Lancet. 9069 Jun 28;349:1884. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)63874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber CM, et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996 Aug 22;382(6593):722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eugen-Olsen J, Iversen AK, Garred P, Koppelhus U, Pedersen C, Benfield TL, et al. Heterozygosity for a deletion in the CKR-5 gene leads to prolonged AIDS-free survival and slower CD4 T-cell decline in a cohort of HIV-seropositive individuals. AIDS. 1997 Mar;11(3):305–310. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arien KK, Gali Y, El-Abdellati A, Heyndrickx L, Janssens W, Vanham G. Replicative fitness of CCR5-using and CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 biological clones. Virology. 2006 Mar 30;347(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson J, Akkina R. CXCR4 and CCR5 shRNA transgenic CD34+ cell derived macrophages are functionally normal and resist HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology. 2005;2:53. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gil J, Esteban M. Induction of apoptosis by the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR): mechanism of action. Apoptosis. 2000 Apr;5(2):107–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1009664109241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapidot T. Mechanism of human stem cell migration and repopulation of NOD/SCID and B2mnull NOD/SCID mice. The role of SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Jun;938:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lapidot T, Kollet O. The essential roles of the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 in human stem cell homing and repopulation of transplanted immune-deficient NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/B2m(null) mice. Leukemia. 2002 Oct;16(10):1992–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahn J, Byk T, Jansson-Sjostrand L, Petit I, Shivtiel S, Nagler A, et al. Overexpression of CXCR4 on human CD34+ progenitors increases their proliferation, migration, and NOD/SCID repopulation. Blood. 2004 Apr 15;103(8):2942–2949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Z, Xiong Y, Peng Y, Pan J, Chen Y, Wu X, et al. Specific inhibition of HIV-1 replication by short hairpin RNAs targeting human cyclin T1 without inducing apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2005 Jun 6;579(14):3100–3106. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ping YH, Chu CY, Cao H, Jacque JM, Stevenson M, Rana TM. Modulating HIV-1 replication by RNA interference directed against human transcription elongation factor SPT5. Retrovirology. 2004;1:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiu YL, Cao H, Jacque JM, Stevenson M, Rana TM. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by RNA interference directed against human transcription elongation factor P-TEFb (CDK9/CyclinT1) J Virol. 2004 Mar;78(5):2517–2529. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2517-2529.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Telenti A, Goldstein DB. Genomics meets HIV-1. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006 Nov;4(11):865–873. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, Yan N, Engelman A, Xavier RJ, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008 Feb 15;319(5865):921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lengauer T, Sander O, Sierra S, Thielen A, Kaiser R. Bioinformatics prediction of HIV coreceptor usage. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Dec;25(12):1407–1410. doi: 10.1038/nbt1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akkina R, Banerjea A, Bai J, Anderson J, Li MJ, Rossi J. siRNAs, ribozymes and RNA decoys in modeling stem cell-based gene therapy for HIV/AIDS. Anticancer Res. 2003 May-Jun;(3A):1997–2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li MJ, Kim J, Li S, Zaia J, Yee JK, Anderson J, et al. Long-term inhibition of HIV-1 infection in primary hematopoietic cells by lentiviral vector delivery of a triple combination of anti-HIV shRNA, anti-CCR5 ribozyme, and a nucleolar-localizing TAR decoy. Mol Ther. 2005 Nov;12(5):900–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson JS, Javien J, Nolta JA, Bauer G. Preintegration HIV-1 Inhibition by a Combination Lentiviral Vector Containing a Chimeric TRIM5alpha Protein, a CCR5 shRNA, and a TAR Decoy. Mol Ther. 2009 Aug 18; doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang CI, Kang HS, Ban C, Kim S, Lee DK. Dual-target gene silencing by using long, synthetic siRNA duplexes without triggering antiviral responses. Mol Cells. 2009 Jun;27(6):689–695. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim DH, Behlke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, Choi S, Rossi JJ. Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat Biotechnol. 2005 Feb;23(2):222–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rose SD, Kim DH, Amarzguioui M, Heidel JD, Collingwood MA, Davis ME, et al. Functional polarity is introduced by Dicer processing of short substrate RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(13):4140–4156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kirchhoff F. Silencing HIV-1 In Vivo. Cell. 2008 Aug 22;134(4):566–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grimm D, Kay MA. Therapeutic application of RNAi: is mRNA targeting finally ready for prime time? J Clin Invest. 2007 Dec;117(12):3633–3641. doi: 10.1172/JCI34129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dykxhoorn DM, Lieberman J. Silencing viral infection. PLoS Med. 2006 Jul;3(7):e242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urban-Klein B, Werth S, Abuharbeid S, Czubayko F, Aigner A. RNAi-mediated gene-targeting through systemic application of polyethylenimine (PEI)-complexed siRNA in vivo. Gene Ther. 2005 Mar;12(5):461–466. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peer D, Park EJ, Morishita Y, Carman CV, Shimaoka M. Systemic leukocyte-directed siRNA delivery revealing cyclin D1 as an anti-inflammatory target. Science. 2008 Feb 1;319(5863):627–630. doi: 10.1126/science.1149859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zimmermann TS, Lee AC, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Bumcrot D, Fedoruk MN, et al. RNAi-mediated gene silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2006 May 4;441(7089):111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature04688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Song E, Zhu P, Lee SK, Chowdhury D, Kussman S, Dykxhoorn DM, et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005 Jun;23(6):709–717. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peer D, Zhu P, Carman CV, Lieberman J, Shimaoka M. Selective gene silencing in activated leukocytes by targeting siRNAs to the integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 6;104(10):4095–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608491104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim S-SPD, Kumar P, Subramanya S, Wu H, Asthana D, Habiro K, Yang Y-G, Manjunath N, Shimaoka M, Shankar P. RNAi-mediated CCR5 silencing by LFA-1-targeted nanoparticles prevents HIV infection in BLT mice. Molecular Therapy. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.271. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heidel JD, Yu Z, Liu JY, Rele SM, Liang Y, Zeidan RK, et al. Administration in non-human primates of escalating intravenous doses of targeted nanoparticles containing ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 siRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Apr 3;104(14):5715–5721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marasco WA, Sui J. The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Dec;25(12):1421–1434. doi: 10.1038/nbt1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eguchi A, Meade BR, Chang YC, Fredrickson CT, Willert K, Puri N, et al. Efficient siRNA delivery into primary cells by a peptide transduction domain-dsRNA binding domain fusion protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2009 Jun;27(6):567–571. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. Strategies for silencing human disease using RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet. 2007 Mar;8(3):173–184. doi: 10.1038/nrg2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang QZ, Lv YH, Diao Y, Xu R. The design of vectors for RNAi delivery system. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(13):1327–1340. doi: 10.2174/138161208799316357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manjunath N, Wu H, Subramanya S, Shankar P. Lentiviral delivery of short hairpin RNAs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009 Jul 25;61(9):732–745. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lewis PF, Emerman M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994 Jan;68(1):510–516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.510-516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bukrinsky M. A hard way to the nucleus. Mol Med. 2004 Jan-Jun;10(1–6):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brenner S, Malech HL. Current developments in the design of onco-retrovirus and lentivirus vector systems for hematopoietic cell gene therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003 Apr 7;1640(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miyoshi H, Blomer U, Takahashi M, Gage FH, Verma IM. Development of a self-inactivating lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1998 Oct;72(10):8150–8157. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8150-8157.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aiken C. Pseudotyping human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus targets HIV-1 entry to an endocytic pathway and suppresses both the requirement for Nef and the sensitivity to cyclosporin A. J Virol. 1997 Aug;71(8):5871–5877. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5871-5877.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maurice M, Verhoeyen E, Salmon P, Trono D, Russell SJ, Cosset FL. Efficient gene transfer into human primary blood lymphocytes by surface-engineered lentiviral vectors that display a T cell-activating polypeptide. Blood. 2002 Apr 1;99(7):2342–2350. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Verhoeyen E, Dardalhon V, Ducrey-Rundquist O, Trono D, Taylor N, Cosset FL. IL-7 surface-engineered lentiviral vectors promote survival and efficient gene transfer in resting primary T lymphocytes. Blood. 2003 Mar 15;101(6):2167–2174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morizono K, Bristol G, Xie YM, Kung SK, Chen IS. Antibody-directed targeting of retroviral vectors via cell surface antigens. J Virol. 2001 Sep;75(17):8016–8020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8016-8020.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anderson JS, Walker J, Nolta JA, Bauer G. Specific Transduction of HIV-Susceptible Cells for CCR5 Knockdown and Resistance to HIV Infection: A Novel Method for Targeted Gene Therapy and Intracellular Immunization. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Jul 10; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b010a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morizono K, Xie Y, Helguera G, Daniels TR, Lane TF, Penichet ML, et al. A versatile targeting system with lentiviral vectors bearing the biotin-adaptor peptide. J Gene Med. 2009 Aug;11(8):655–663. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Westerhout EM, Vink M, Haasnoot PC, Das AT, Berkhout B. A conditionally replicating HIV-based vector that stably expresses an antiviral shRNA against HIV-1 replication. Mol Ther. 2006 Aug;14(2):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.er Brake O, Berkhout B. Lentiviral vectors that carry anti-HIV shRNAs: problems and solutions. J Gene Med. 2007 Sep;9(9):743–750. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Giering JC, Grimm D, Storm TA, Kay MA. Expression of shRNA from a tissue-specific pol II promoter is an effective and safe RNAi therapeutic. Mol Ther. 2008 Sep;16(9):1630–1636. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shimizu S, Kamata M, Kittipongdaja P, Chen KN, Kim S, Pang S, et al. Characterization of a potent non-cytotoxic shRNA directed to the HIV-1 co-receptor CCR5. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2009;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boden D, Pusch O, Silbermann R, Lee F, Tucker L, Ramratnam B. Enhanced gene silencing of HIV-1 specific siRNA using microRNA designed hairpins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(3):1154–1158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu YP, Haasnoot J, ter Brake O, Berkhout B, Konstantinova P. Inhibition of HIV-1 by multiple siRNAs expressed from a single microRNA polycistron. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 May;36(9):2811–2824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aagaard LA, Zhang J, von Eije KJ, Li H, Saetrom P, Amarzguioui M, et al. Engineering and optimization of the miR-106b cluster for ectopic expression of multiplexed anti-HIV RNAs. Gene Ther. 2008 Dec;15(23):1536–1549. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Son J, Uchil PD, Kim YB, Shankar P, Kumar P, Lee SK. Effective suppression of HIV-1 by artificial bispecific miRNA targeting conserved sequences with tolerance for wobble base-pairing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008 Sep 19;374(2):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stegmeier F, Hu G, Rickles RJ, Hannon GJ, Elledge SJ. A lentiviral microRNA-based system for single-copy polymerase II-regulated RNA interference in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Sep 13;102(37):13212–13217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001 May 24;411(6836):494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gupta S, Schoer RA, Egan JE, Hannon GJ, Mittal V. Inducible, reversible, and stable RNA interference in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Feb 17;101(7):1927–1932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306111101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Unwalla HJ, Li MJ, Kim JD, Li HT, Ehsani A, Alluin J, et al. Negative feedback inhibition of HIV-1 by TAT-inducible expression of siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2004 Dec;22(12):1573–1578. doi: 10.1038/nbt1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Berges BK, Akkina SR, Folkvord JM, Connick E, Akkina R. Mucosal transmission of R5 and X4 tropic HIV-1 via vaginal and rectal routes in humanized Rag2−/− gammac −/− (RAG-hu) mice. Virology. 2008 Apr 10;373(2):342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Braun SE, Wong FE, Connole M, Qiu G, Lee L, Gillis J, et al. Inhibition of simian/human immunodeficiency virus replication in CD4+ T cells derived from lentiviral-transduced CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2005 Dec;12(6):1157–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Anderson J, Akkina R. Complete knockdown of CCR5 by lentiviral vector-expressed siRNAs and protection of transgenic macrophages against HIV-1 infection. Gene Ther. 2007 Sep;14(17):1287–1297. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.An DS, Donahue RE, Kamata M, Poon B, Metzger M, Mao SH, et al. Stable reduction of CCR5 by RNAi through hematopoietic stem cell transplant in non-human primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Aug 7;104(32):13110–13115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705474104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Naslund TI, Liljestrom P, Weber F, et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5'-phosphates. Science. 2006 Nov 10;314(5801):997–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, Brzozka K, Jung A, Kato H, et al. 5'-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006 Nov 10;314(5801):994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Judge A, MacLachlan I. Overcoming the innate immune response to small interfering RNA. Hum Gene Ther. 2008 Feb;19(2):111–124. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, McClintock K, MacLachlan I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005 Apr;23(4):457–462. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jackson AL, Burchard J, Leake D, Reynolds A, Schelter J, Guo J, et al. Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces "off-target" transcript silencing. RNA. 2006 Jul;12(7):1197–1205. doi: 10.1261/rna.30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jackson AL, Bartz SR, Schelter J, Kobayashi SV, Burchard J, Mao M, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat Biotechnol. 2003 Jun;21(6):635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Svoboda P. Off-targeting and other non-specific effects of RNAi experiments in mammalian cells. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007 Jun;9(3):248–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen PY, Weinmann L, Gaidatzis D, Pei Y, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, et al. Strand-specific 5'-O-methylation of siRNA duplexes controls guide strand selection and targeting specificity. RNA. 2008 Feb;14(2):263–274. doi: 10.1261/rna.789808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Snove O, Jr., Rossi JJ. Chemical modifications rescue off-target effects of RNAi. ACS Chem Biol. 2006 Jun 20;1(5):274–276. doi: 10.1021/cb6002256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peek AS, Behlke MA. Design of active small interfering RNAs. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007 Apr;9(2):110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Behlke MA. Chemical modification of siRNAs for in vivo use. Oligonucleotides. 2008 Dec;18(4):305–319. doi: 10.1089/oli.2008.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sano M, Sierant M, Miyagishi M, Nakanishi M, Takagi Y, Sutou S. Effect of asymmetric terminal structures of short RNA duplexes on the RNA interference activity and strand selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 Oct;36(18):5812–5821. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Smith TF, Waterman MS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J Mol Biol. 1981 Mar 25;147(1):195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Naito Y, Yamada T, Matsumiya T, Ui-Tei K, Saigo K, Morishita S. dsCheck: highly sensitive off-target search software for double-stranded RNA-mediated RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005 Jul 1;33:W589–W591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki419. (Web Server issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rossi JJ. RNAi as a treatment for HIV-1 infection. Biotechniques. 2006 Apr;(Suppl):25–29. doi: 10.2144/000112167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bennasser Y, Yeung ML, Jeang KT. RNAi therapy for HIV infection: principles and practicalities. BioDrugs. 2007;21(1):17–22. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.An DS, Qin FX, Auyeung VC, Mao SH, Kung SK, Baltimore D, et al. Optimization and functional effects of stable short hairpin RNA expression in primary human lymphocytes via lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006 Oct;14(4):494–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006 May 25;441(7092):537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Modlich U, Navarro S, Zychlinski D, Maetzig T, Knoess S, Brugman MH, et al. Insertional Transformation of Hematopoietic Cells by Self-inactivating Lentiviral and Gammaretroviral Vectors. Mol Ther. 2009 Aug 11; doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McAnuff MA, Rettig GR, Rice KG. Potency of siRNA versus shRNA mediated knockdown in vivo. J Pharm Sci. 2007 Nov;96(11):2922–2930. doi: 10.1002/jps.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Levine BL, Humeau LM, Boyer J, MacGregor RR, Rebello T, Lu X, et al. Gene transfer in humans using a conditionally replicating lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Nov 14;103(46):17372–17377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Miyoshi H, Smith KA, Mosier DE, Verma IM, Torbett BE. Transduction of human CD34+ cells that mediate long-term engraftment of NOD/SCID mice by HIV vectors. Science. 1999 Jan 29;283(5402):682–686. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ramezani A, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Performance- and safety-enhanced lentiviral vectors containing the human interferon-beta scaffold attachment region and the chicken beta-globin insulator. Blood. 2003 Jun 15;101(12):4717–4724. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hino S, Fan J, Taguwa S, Akasaka K, Matsuoka M. Sea urchin insulator protects lentiviral vector from silencing by maintaining active chromatin structure. Gene Ther. 2004 May;11(10):819–828. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lotti F, Menguzzato E, Rossi C, Naldini L, Ailles L, Mavilio F, et al. Transcriptional targeting of lentiviral vectors by long terminal repeat enhancer replacement. J Virol. 2002 Apr;76(8):3996–4007. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3996-4007.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, et al. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 2007 Oct;13(10):1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Palliser D, Chowdhury D, Wang QY, Lee SJ, Bronson RT, Knipe DM, et al. An siRNA-based microbicide protects mice from lethal herpes simplex virus 2 infection. Nature. 2006 Jan 5;439(7072):89–94. doi: 10.1038/nature04263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wu Y, Navarro F, Lal A, Basar E, Pandey RK, Manoharan M, et al. Durable protection from Herpes Simplex Virus-2 transmission following intravaginal application of siRNAs targeting both a viral and host gene. Cell Host Microbe. 2009 Jan 22;5(1):84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]