Abstract

With the purpose to improve the biological activities of curcumin, eight novel ferrocenyl curcuminoids were synthesized by covalent anchorage of three different ferrocenyl ligands. We evaluated their cytotoxicity on B16 melanoma cells and normal NIH 3T3 cells, their inhibition of tubulin polymerization and their effect on the morphology of endothelial cells. The presence of a ferrocenyl side chain was clearly shown to improve the biological activity of most of their corresponding organic curcuminoid analogues.

Keywords: curcuminoid, ferrocenyl, B16 melanoma, NIH 3T3 cells, endothelial cells, cancer

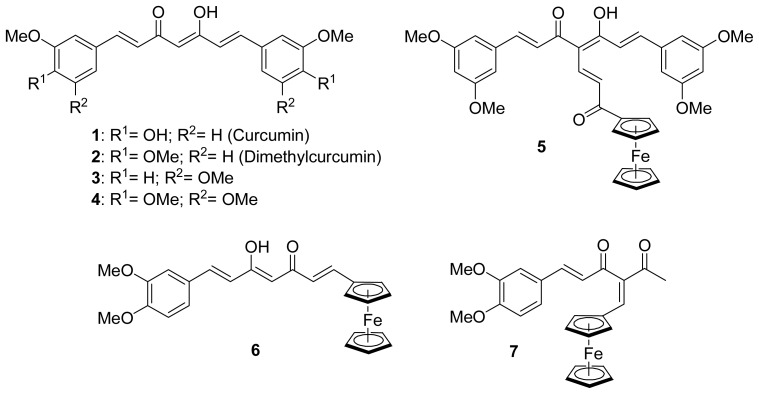

Curcumin 1 (Figure 1), the major constituent of the rhizome Curcuma Longa, is a yellow pigment of the spice turmeric. This non-toxic[1] dietary phytomolecule has been used for centuries in Asia for its medicinal properties, and regained considerable attention recently due to its several health promoting effects, such as antioxidant,[2,3] anti-inflammatory,[4] chemopreventive,[5–7] and antitumor activities on several cancer types.[8,9] The precise mechanism of action of curcumin in cancer cells is still not completely understood and appears to be mediated by several different pathways. For example, curcumin was reported to induce apoptosis by suppression of nuclear factor-κB described in several cancer cell lines such as melanoma.[10] Curcumin was also reported to interact with tubulin polymerization, although these data are considered controversial because high concentrations are needed for inhibition.[11–13]

Figure 1.

Organic curcuminoids and first ferrocenyl curcuminoid derivatives

Great interest has been devoted to the synthesis of new curcumin analogues exhibiting enhanced biological properties. For example, dimethylcurcumin 2 (Figure 1), is more effective at inhibiting colon cancer cell proliferation in vitro [14] and is metabolically more stable.[15] Another interesting strategy has been to chelate a metal to curcumin in order to increase the cytotoxicity of the parent molecule. Indeed, the use of metal-based compounds for the treatment of cancer has found significant interest in medicine[16] (e.g., clinical use of cisplatinum compounds), thus encouraging chemists to design new metallated anticancer agents. Several examples of metallated curcuminoid analogues, which all involve the coordination of the metal to the oxygens of the β-diketone, have been evaluated for their biological properties.[17–25] Because there were no published reports of an organometallic moiety covalently grafted to curcumin or its derivatives, we recently described the synthesis of the first examples of such ferrocenyl derivatives 5, 6 and 7 (Figure 1).[26] We therefore became interested to further investigate the covalent anchorage of a ferrocenyl unit to several curcuminoids. We hypothesized that the presence of ferrocene in curcumin derivatives could enhance the biological activity against cancer cells, as we previously reported for ferrocenyl derivatives of steroidal antiandrogens[27] and of the antioestrogen tamoxifen.[28,29]

In the present report, we synthesized eight novel ferrocenyl curcuminoids in order to evaluate some of their biological properties. To do so, three different ferrocenyl spacer chains were chosen to be anchored to the central carbon of the curcuminoid skeleton: ferrocenyl propenone to increase the conjugation up to the ferrocenyl (series A), ferrocenyl methylene forcing the β-diketone to be in its diketone tautomer form (series B), and ferrocenyl ethanone interrupting the conjugation between the skeleton and the ferrocenyl moiety (series C). The effect of the substitution by a methoxyl instead of an hydroxyl on the two phenyl groups was also investigated by choosing dimethylcurcumin 2, 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3 and trimethoxycurcumin 4 (Figure 1) as curcuminoid skeleton, in addition to curcumin. Although 3 and 4 have already been reported in the literature,[30] they have not been studied in details.

We report here the synthesis of several ferrocenyl derivatives of the curcuminoids 1, 2, 3 and 4. We also tested these ferrocenyl derivatives for some important biological activities required for anticancer activity, i.e., their cytotoxicity against murine B16 melanoma cells and NIH 3T3 normal cells, their effect on the inhibition of tubulin polymerization and the analysis of the morphological effects on endothelial cells (as a model of antitumor antivascular effect).[31] For comparison purposes, curcumin and compounds 2, 3 and 4 also underwent these biological tests.

Synthesis of curcuminoid ferrocenyl derivatives

The curcuminoids 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 1) were synthesized following Pederson’s conditions[32] by condensing an appropriate aldehyde with 2,4-pentanedione in the presence of a base as well as tributylborate and boric anhydride. The latter is required to complex the 2,4-dione moiety in order to prevent a Knoevenagel condensation on C-3. It was shown that the β-diketone of curcumin exists as keto-enol tautomer in solid state,[33] as well as in solution,[34] as observed for the three other curcuminoids (2, 3 and 4).

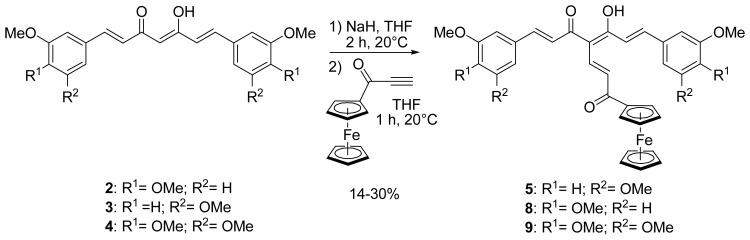

We previously reported the synthesis of compound 5 bearing a ferrocenyl propenone moiety (Scheme 1), obtained from 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3.[26] Following the same procedure, dimethylcurcumin and trimethoxycurcumin analogues 8 and 9 were also successfully synthesized. The enol of 2 and 4 was deprotonated by stirring in the presence of sodium hydride for 2 hours at room temperature. Ferrocenyl propynone[35] was then added to produce 8 and 9 with yields of 25 and 14%, respectively. The rather modest yields obtained, also observed previously for 5 were explained by the degradation of the starting material if the reaction time was prolonged. 1H NMR spectra of 8 and 9 were similar to that of 5 and showed that the peak at 5.85 ppm, corresponding to the central proton of the β-diketone in its keto-enol form, had disappeared and confirmed that the substitution took place at the desired C-4 position. The crystal structure of 5 has previously been reported.[26]

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of ferrocenyl propenone curcuminoids (series A)

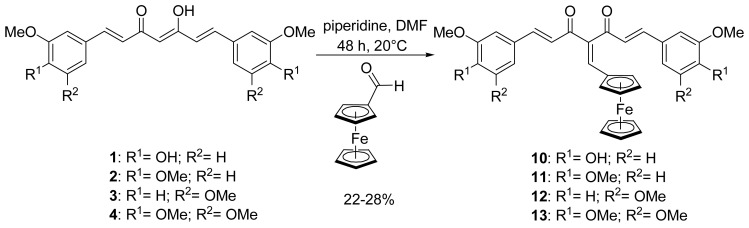

In order to force the β-diketone of the curcuminoid to stay in its diketo form instead of the keto-enol form, the organic curcuminoids 1, 2, 3 and 4 underwent a Knoevenagel condensation with ferrocenecarboxaldehyde to form 10, 11, 12 and 13, respectively, following a modified procedure reported for the substitution of organic species (Scheme 2).[36] In our case, ferrocenecarboxaldehyde was condensed to the corresponding organic curcuminoid in the presence of freshly distilled piperidine in anhydrous DMF instead of a CHCl3/EtOH solution, in order to increase the yields of the newly formed ferrocenyl curcuminoids, e.g., from 3% to 27% for 11. Again, moderate yields (22–28%) were obtained because of degradation with longer reaction times. Confirmation of the desired substitution was obtained by 1H NMR, as the peak of the central proton disappeared and the diketo form of the β-diketone was confirmed by the appearance of a second carbonyl peak on the 13C NMR spectrum. It is noteworthy that these conditions of Knoevenagel condensation did not require prior protection of the phenol groups of curcumin, therefore enabling us to prepare 10 in one step.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of ferrocenyl methylene curcuminoids (series B)

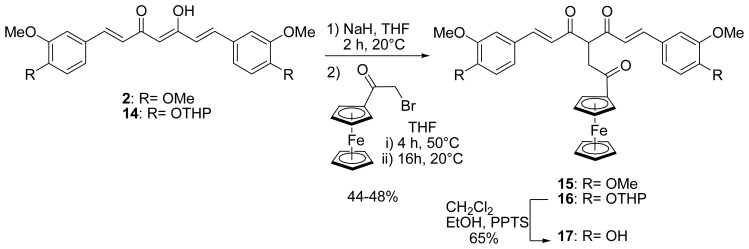

With the purpose of studying the effect of an interruption of the conjugation between the curcuminoid and the ferrocenyl, a ferrocenyl ethanone moiety was therefore grafted to dimethylcurcumin 2 and a protected curcumin, 14 (Scheme 3). Indeed, for this reaction, it was necessary to protect the phenols of curcumin. We previously described a modified synthesis of a bis-tetrahydropyran (14) and bis-t-butyldimethylsilyl curcumin[26] and discussed the relative stability of ferrocenyl protected curcumin towards the different conditions of deprotection for a THP and a TBDMS group. For this reaction, the protection by a THP moiety was chosen because deprotection occurs in milder conditions than for TBDMS. Compounds 2 and 14 were deprotonated by sodium hydride in the same conditions as described above, before α-bromoacetylferrocene[37] (obtained from ferrocene and 2-bromoacetyl bromide) was added dropwise. After heating for 4 hours and then stirring overnight at room temperature, 15 and 16 were formed in approximately 50% yield. The reaction has also been carried out using α-chloroacetylferrocene, but 15 was obtained in only 17% yield while 16 could not be formed. The NMR spectra of 15 and 16 showed that the β-diketones were in their diketo- rather that their keto-enol forms. Indeed, in their 1H NMR spectra, the H-4 singlet of the keto-enol form at 5.85 ppm disappeared, while a triplet at 4.95 ppm was observed, attributed to the H-4 of the diketo form. Additionally, one peak at 195 ppm, corresponding to the two symmetrical carbonyl groups of the curcuminoid skeleton, was observed in their 13C NMR spectra. Similar observations were reported by Pederson for the synthesis of several substituted organic curcuminoids.[32] For example, the synthesis consisting in the alkylation of curcumin on the central carbon (C-4) with benzyl bromide only led to the tautomer in its diketo form.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of ferrocenyl ethanone curcuminoids (series C)

In order to obtain the curcumin ferrocenyl ethanone derivative, the deprotection of the THP protecting groups of 16 was carried out by using pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) in CH2Cl2/EtOH to lead to the formation of the desired unprotected ferrocenyl curcumin 17 in 68% yield, confirming the stability of ferrocenyl ethanone curcuminoids under mild acidic conditions. The NMR spectra of 17 showed that the β-diketone is in the same diketo form as for the protected derivative 16.

Biological evaluation of the ferrocenyl derivatives of curcumin

The synthesized ferrocenyl curcuminoid derivatives were evaluated in vitro for some biological properties frequently linked to anticancer activity, i.e., for their cytotoxicity against murine B16 melanoma cells and NIH 3T3 normal cells, their effect on tubulin polymerization, and their induction of a rapid morphological change of endothelial cells (rounding up) that may hint to a possible antivascular effect. For comparison purposes, the organic compounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 were also tested in parallel, as well as combretastatin A4 (CA-4), a well-known vascular disrupting agent.[38]

Cytotoxicity

The murine B16 melanoma cells were chosen to evaluate the cytotoxicity because melanoma is particularly refractory to chemotherapy. Table 1 presents the cytotoxicity values (IC50) of the parent compound curcumin and its analogues. Curcumin showed an IC50 value of 8.5 μM, which is comprised within the literature values obtained for this cell line. For example, B16-BL6 melanoma[39] (highly metastatic) and B16-R melanoma[40] (resistant to doxorubicin) presented IC50 values of 3.6 and 18 μM, respectively for a similar 48 hour incubation time.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity, inhibition of tubulin polymerization, and morphological effects on endothelial cells of ferrocenyl curcuminoid derivatives.

| Series | Compound | Cytotoxicitya | Cytotoxicitya | ITPb | Morphological activity on endothelial cells (μM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16 melanoma cells | NIH 3T3normal cells | ||||

| IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | |||

| Organic | 1 (Curcumin) | 8.5 | 12.3 | 17.9 | 50 |

| 2 (Dimethyl-curcumin) | 8.6 | 19.5 | >30 | 100 | |

| 3 | 12.0 | 27.5 | >30 | 50 | |

| 4 | 2.8 | 15.5 | >30 | 100 | |

|

| |||||

| Ferrocenyl Unsymmetrical | 6 | >100 | >100 | >30 | 50 |

| 7 | 28.6 | 56.2 | 9.3 | 50 | |

|

| |||||

| Ferrocenyl Symmetrical A | 5 | >100 | >100 | 5.8 | 12.5 |

| 8 | 30.5 | >100 | 2.5 | 12.5 | |

| 9 | 19.0 | >100 | 2.1 | 12.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Ferrocenyl Symmetrical B | 10 | 4.2 | 6.9 | 21.4 | 12.5 |

| 11 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 50 | |

| 12 | 5.0 | 24.5 | 11.0 | 50 | |

| 13 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 12.6 | 6.3 | |

|

| |||||

| Ferrocenyl Symmetrical C | 15 | 6.9 | 18.2 | 5.5 | 25 |

| 17 | 75.7 | 4.2 | 9.9 | 25 | |

|

| |||||

| Reference | Combreta-statin A4 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.005 |

Cytotoxicity on murine B16 melanoma cells or normal NIH 3T3 cells after a 48 hour exposure time. Results are expressed as the concentration that causes 50% cell kill (IC50). Values are the mean of 3 determinations.

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization (ITP). Above a threshold value of 30 μM, the half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were not precisely determined.

The lowest active concentration that causes a rounding up of immortalized HUVEC (EA.hy 926) after a 2 hour exposure time.

Of the three organic curcuminoids evaluated for the first time in this study on B16 cells, it was of interest to note that trimethoxycurcumin 4 exhibited higher cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 2.8 μM) compared to 1, 2 and 3 (IC50 values comprised between 8.5 and 12.0 μM). Looking at the substitution of the aromatic rings, it appears that the absence of substituent at the para position decreases somewhat the cytotoxic activity of the resulting curcuminoid, because 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3 showed the least cytotoxic effect with an IC50 value of 12.0 μM.

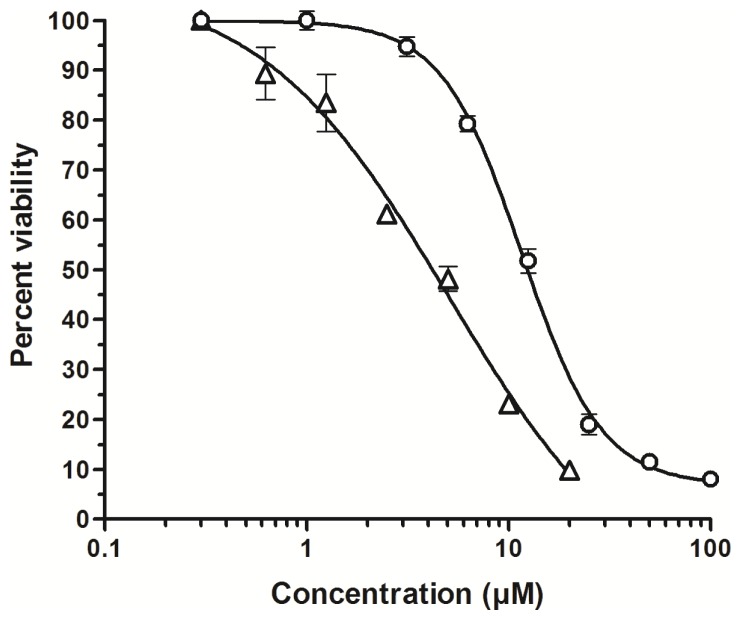

The two ferrocenyl unsymmetrical compounds 6 and 7, as well as the ones of the series A (5, 8, and 9), were shown to be weakly cytotoxic. However, the four ferrocenyl derivatives of series B (containing a ferrocenyl methylene chain) presented the most cytotoxic activity of our compounds with IC50 values ranging from 2.2 μM for 13 to 7.1 μM for 11. For the dimethylcurcumin and trimethoxycurcumin analogues (11 and 13), the ferrocenylation did not significantly improve the cytotoxic activity. However, we observed an interesting two-fold increase in cytotoxicity for the ferrocenyl analogues of 1 and 3, i.e., 10 and 12. Representative curves showing the decrease in number of viable cells upon treatment with increasing concentrations of the organic 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3 and its ferrocenyl analogue 12 is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percent viability of B16 melanoma cells as a function of the concentration of the organic 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3 (circles) or the ferrocenyl analogue 12 (triangles) (48 hour exposure time). Error bars, SD.

As a result, in the B16 cellular model, the diketo form of the ferrocenyl derivatives, as well as conjugation up to the ferrocenyl (series B), seemed required for high cytotoxic activity. In series C, 15 and 17, which are also in diketo form, but have disrupted conjugation, did not exhibit increased cytotoxicity compared to their corresponding organic curcuminoids. Indeed, similar IC50 values were obtained for 15 and dimethylcurcumin 2, while the cytotoxic activity of 17 decreased dramatically compared to curcumin 1 (75.7 vs 8.5 μM, respectively).

Although not in the same chemical series, our compounds were compared to combretastatin A4 which is considered as a standard antivascular agent. All the curcuminoid analogues were less cytotoxic to B16 melanoma cells compared to combretastatin A4. For example, the best cytotoxic curcuminoid analogue 13 (IC50=2.2 μM) was about 700-fold less cytotoxic compared to combretastatin A4 (IC50=0.003 μM)

For comparison purposes, we also evaluated the cytotoxic activity of these compounds against the NIH 3T3 normal cell line. Table 1 shows that the IC50 of the normal cells were higher than the IC50 for the cancer cells (B16 melanoma) for most compounds (with the exception of 17). This could indicate an interesting selectivity of cytotoxic action against cancer cells compared to normal ones, as previously observed for other curcuminoids (reviewed in reference 40-b).

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization (ITPa)

We were also interested to test our curcumin ferrocenyl derivatives on tubulin polymerization, because several potent clinically used anticancer drugs are indeed known to act on tubulin dynamics[41,42] (e.g., vinca alkaloids, taxanes), and because it was recently reported that curcumin could also inhibit microtubule assembly.[11]

In our assay conditions, curcumin was shown to inhibit microtubule formation with an IC50 value of 17.9 μM (Table 1). Our data corroborate Gupta and coworkers’ observations, although their reported IC50 value is higher than ours (calculated IC50 ≈ 80 μM).[11] A plausible explanation for our lower IC50 value is likely due, in our case, to a preincubation period of 45 minutes at room temperature in presence of the tested compound, which allows for the tested ligand to more closely interact with tubulin prior to the beginning of the polymerization with the addition of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and incubation at 37 °C. The function of this preincubation step is to maximize the potential for detecting the interaction of drugs with tubulin, and to give a better idea of the relative potency of slow-binding agents (such as colchicinoids), both in comparison with each other, and in comparison with other classes of drugs.[43] Of the organic curcuminoids, only curcumin presented an IC50 value of less that 30 μM.

Within the series of the ferrocenyl curcuminoids, the unsymmetrical compound 6 was not markedly active on tubulin polymerization, whereas its isomer 7 presented an IC50 value of 9.3 μM.

Although the high activity of combretastatin CA-4 could not be reached by the symmetrical organometallic compounds, the presence of a ferrocenyl moiety was generally linked to a marked increase in tubulin inhibition activity compared to their organic counterparts, with the exception of curcumin substituted with ferrocenyl methylene moiety 10, which showed a similar ITP activity.

The lowest IC50 values (2.1 to 5.8 μM) were observed with the ferrocenyl propenone curcuminoids (series A). Compounds of series B and C were all good tubulin polymerization inhibitor with concentrations comprised between 3.6 and 12.6 μM, with still the exception of the curcumin analogue 10. By examining the substituents on phenyl rings, it was observed that the 3,4-dimethoxyl substitution of the ferrocenyl curcuminoids (dimethylcurcumin derivatives 8, 11 and 15) produced the best antitubulin activity (2.5 – 5.5 μM), whatever the spacer chain used.

Morphological effects on endothelial cells

Because several antitumor antivascular compounds act on endothelial cells, we also tested the morphological effects of our novel ferrocenyl compounds on immortalized HUVEC (Ea.hy 926), as a model of potential antitumor antivascular effect.[31,38]

A rounding up effect of endothelial cells was observed only at high concentrations (50–100 μM) for the organic curcuminoids (Table 1). The introduction of the ferrocenyl allowed the morphological rounding up to occur at significantly lower concentrations for all series A, B and C. In the series A, the concentration needed for rounding up was 12.5 μM. For series B, with the exception of the dimethylcurcumin 2 and 3,5-dimethoxycurcumin 3 analogues (11 and 12), a significant decrease in the concentration needed for rounding up of endothelial cells was noted, as well as in series C (25 μM).

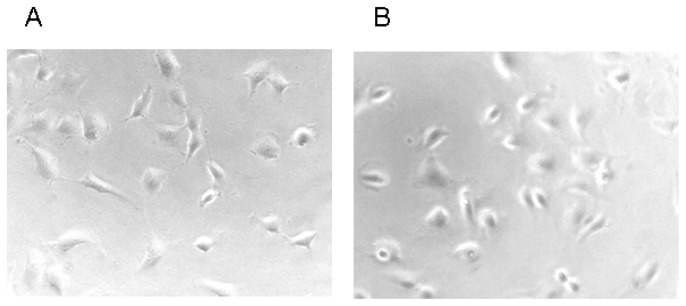

These data clearly indicate that the presence of a ferrocenyl moiety could significantly lower the concentration needed for the rounding up of endothelial cells for the majority of our symmetrical ferrocenyl curcuminoids. Figure 3 shows a representative change in endothelial cells shape for compound 13 (series B) at 6.3 μM.

Figure 3.

Morphological effects of the ferrocenyl curcuminoid 13. Exponentially growing endothelial cells (EA.hy 926) were exposed to the solvent DMSO at 1% (panel A, control), or to the curcuminoid 13 at a concentration of 6.3 μM (panel B), and incubated for 2 h (37 °C, 5% CO2). Representative photographs shown were recorded at an original magnification of 200 X.

In addition, the increase in morphological activity of these curcuminoid analogues appeared to be correlated with their antitubulin activity. As a matter of fact, we observed a statistically significant linear correlation between the ITP values (x) and the concentration needed for rounding up (y), indicating that the best ITP values were linked to a lower concentration for morphological activity (y=1.81x+13.71, R=0.661, P<0.007).

Conclusion

In this work, eight novel ferrocenyl curcuminoids were synthesized by covalent anchorage of three different ferrocenyl ligands to organic curcuminoids substituted with methoxyl and hydroxyl groups on the aromatic rings. The presence of a ferrocenyl unit clearly improved the biological activity of most novel ferrocenylated curcuminoids. Furthermore, this first study of organometallic moiety covalently grafted to curcuminoids demonstrated the influence of the spacer chain between the curcuminoid skeleton and the ferrocenyl unit on the resulting biological activity. Indeed the curcuminoids bearing the methylene linker exhibited the best cytotoxicity on murine B16 cells (IC50 = 2.2–7.1 μM), whereas the presence of the propenone spacer chain induced the best tubulin polymerization inhibition and rounding up of endothelial cells to occur at lower concentrations. Collectively, our results validate the strategy of covalently anchoring an organometallic moiety to a curcuminoid in order to improve its biological activities.

Abbreviation

- ITP

inhibition of tubulin polymerization

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Numbering scheme for NMR assignment of curcuminoids skeleton. Experimental procedure and characterization of compounds 8-13 and 15-17. HRMS purity data of compounds 8-10 and 15-17 and elemental analyses of compounds 8-13 and 15-17. Evaluation of cytotoxicity in murine B16 melanoma cells, inhibition of tubulin polymerization (ITP) and effect on the morphology of transformed HUVEC cells (EA.hy 926 cells). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sharma RA, Gescher AJ, Steward WP. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1955–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barclay LRC, Vinqvist MR, Mukai K, Goto H, Hashimoto Y, Tokunaga A, Uno H. Org Lett. 2000;2:2841–2843. doi: 10.1021/ol000173t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber WM, Hunsaker LA, Abcouwer SF, Deck LM, Vander Jagt DL. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:3811–3820. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JJ, Mukhtar H. Cancer Lett. 2007;255:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ireson CR, Jones DJL, Orr S, Coughtrie MWH, Boocock DJ, Williams ML, Farmer PB, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan N, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Antiox Redox Sign. 2008;10:475–510. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand P, Sundaram C, Jhurani S, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:133–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal BB, Kumar A, Bharti AC. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:363–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin YE, Wall BA, Wang S, Namkoong J, Martino JJ, Suh J, Lee HJ, Rabson AB, Yang CS, Chen S, Ryu JH. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:274–283. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282ed3d0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta KK, Bharne SS, Rathinasamy K, Naik NR, Panda D. FEBS J. 2006;273:5320–5332. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gertsch J, Meier S, Tschopp N, Altmann KH. Chimia. 2007;61:338–372. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas SL, Zhong D, Zhou W, Malik S, Liotta D, Snyder JP, Hamel E, Giannakakou P. 2008;7:2409–2417. doi: 10.4161/cc.6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamvakopolous C, Dimas K, Sofianos ZD, Hatziantoniou S, Han Z, Liu Z-L, Wyche JH, Pantazis P. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1269–1277. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pae HO, Jeong S-O, Kim H-S, Kim S-H, Song Y-S, Kim S-K, Chai K-Y, Chung H-T. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:1082–1091. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaouen G. Bioorganometallics Biomolecules, Labelling, Medicine. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sui Y, Salto R, Li J, Craik C, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Bioorg Med Chem. 1993;1:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)82152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi K, Thompson KH, Patrick BO, Storr T, Martins C, Polishchuk E, Yuen VG, McNeill JH, Orvig C. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:2217–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Y-M, Xu J-P, Ding L, Hou Q, Liu J-W, Zhu Z-L. J Inorg Biochem. 2009;103:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhlwein F, Polborn K, Beck W. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 1997;623:1211–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumanont Y, Murakami Y, Tohda M, Vajragupta O, Watanabe H, Matsumoto K. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1732–1739. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valentini A, Conforti F, Crispini A, De Martino A, Condello R, Stellitano C, Rotilio G, Ghedini M, Federici G, Bernardini S, Pucci D. J Med Chem. 2009;52:484–491. doi: 10.1021/jm801276a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zambre AP, Kulkarni VM, Padhye S, Sandur SK, Aggarwal BB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:7196–7204. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eybl V, Kotyzova D, Leseticky L, Bludovska M, Koutensky J. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26:207–212. doi: 10.1002/jat.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padhye S, Yang HJ, Jamadar A, Cui QC, Chavan D, Dominiak K, McKinney J, Banerjee S, Dou QP, Sarkar FH. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1874–1880. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arezki A, Brulé E, Jaouen G. Organometallics. 2009;28:1606–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Top S, Thibaudeau C, Vessières A, Brulé E, Le Bideau F, Joerger J-M, Plamont M-A, Samreth S, Edgar A, Marrot J, Herson P, Jaouen G. Organometallics. 2009;28:1414–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Top S, Vessières A, Leclercq G, Quivy J, Tang J, Vaissermann J, Huché M, Jaouen G. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:5223–5236. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vessières A, Top S, Pigeon P, Hillard EA, Boubeker L, Spera D, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3937–3940. doi: 10.1021/jm050251o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park CH, Lee JH, Yang CH. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;38:474–480. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2005.38.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galbraith SM, Chaplin DJ, Lee F, Stratford MR, Locke RJ, Vojnovic B, Tozer GM. Anticancer Res. 2001:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen U, Rasmussen PB, Lawesson S-O. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1985:1557–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tønnesen HH, Karlsen J, Mostad A. Acta Chem Scand. 1982;36B:475–479. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Payton F, Sandusky P, Alworth WL. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:143–146. doi: 10.1021/np060263s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barriga S, Marcos CF, Riantc O, Torroba T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:9785–9792. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin L, Shi Q, Su C-Y, Shih CC-Y, Lee K-H. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:2527–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang K, Yang H, Zhou Z, Yu M, Li F, Gao X, Yi T, Huang C. Org Lett. 2008;10:2557–2560. doi: 10.1021/ol800778a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanthou C, Tozer GM. Blood. 2002;99:2060–2069. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caltagirone S, Rossi C, Poggi A, Ranelletti FO, Natali PG, Brunetti M, Aiello FB, Piantelli M. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:595–600. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000815)87:4<595::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odot J, Albert P, Carlier A, Tarpin M, Devy J, Madoulet C. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:381–387. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40b.Lopez-Lazaro M. Anticancer carcinogenic properties of curcumin: considerations for its clinical development as a cancer chemopreventive chemotherapeutic agent. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S103–S127. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou J, Giannakakou P. Curr Med Chem - Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:65–71. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahindroo N, Liou J-P, Chang J-Y, Hsieh H-P. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2006;16:647–691. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamel E. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;38:1–22. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]