Abstract

Overexpression of the ETS-related transcription factor ETV1 can initiate neoplastic transformation of the prostate. ETV1 activity is highly regulated by phosphorylation, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Here we report that all 14-3-3 proteins, with the exception of the tumor suppressor 14-3-3σ, can bind to ETV1 in a condition manner dictated by its prominent phosphorylation site S216. All non-σ 14-3-3 proteins synergized with ETV1 to activate transcription of its target genes MMP-1 and MMP-7, which regulate extracellular matrix in the prostate tumor microenvironment. S216 mutation or 14-3-3τ downregulation was sufficient to reduce ETV1 protein levels in prostate cancer cells, indicating that non-σ 14-3-3 proteins protect ETV1 from degradation. Notably, S216 mutation also decreased ETV1-dependent migration and invasion in benign prostate cells. Downregulation of 14-3-3τ reduced prostate cancer cell invasion and growth in the same manner as ETV1 attenuation. Lastly, we showed that 14-3-3τ and 14-3-3ε were overexpressed in human prostate tumors. Taken together, our results demonstrated that non-σ 14-3-3 proteins are important modulators of ETV1 function that promote prostate tumorigenesis.

Keywords: ETV1, phosphorylation, prostate cancer, transcription, 14-3-3

Introduction

ETS variant 1 (ETV1) belongs to the family of ETS transcription factors that is characterized by a winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif (1). ETV1 ablation in mice resulted in limb ataxia and premature death around one month after birth, attesting to its crucial developmental role. Furthermore, ETV1 is implicated in tumor formation. A chromosomal translocation with the Ewing sarcoma gene causes the formation of Ewing tumors. Mostly children and adolescents are afflicted by this aggressive disease that leads to the death of nearly half of all Ewing tumor patients (2). More recently, ETV1 amplification was observed in 40% of all melanomas and ETV1 acted as a promoter of melanoma cell growth (3). Yet the most prominent role for ETV1 has been established in prostate tumors, where ETV1 is translocated in ~10% of all cases leading to the overexpression of full-length or N-terminally truncated ETV1 (4-6). Mouse models confirmed that ETV1 overexpression is indeed an underlying cause of prostate cancer initiation, since respective transgenic mice developed prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (7, 8).

ETV1 is regulated by posttranslational modification through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway that dramatically enhances ETV1 transcriptional activity (9, 10). Multiple routes exist through which MAPKs target ETV1. First, MAPKs directly phosphorylate ETV1 (11). Second, MAPKs phosphorylate and thereby activate MAPK-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) such as RSK1 and MSKs, which themselves phosphorylate ETV1 (12, 13). Third, MAPKs stimulate the enzymatic activity of the coactivator p300 that binds to and acetylates ETV1 (14, 15). And fourth, MAPKs phosphorylate and activate steroid receptor coactivators, which form complexes with ETV1 and thereby stimulate ETV1-dependent gene transcription (16).

Currently, we do not understand how MAPK-induced phosphorylation of ETV1 modulates its transactivation potential. Here, we have identified one mechanism by which phosphorylation of ETV1 does so through facilitating an interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. Although seven paralogous 14-3-3 proteins exist in mammals that can regulate cell growth and survival (17, 18), their role in prostate cancer has remained largely unexplored.

Materials and Methods

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells (CRL-11268; obtained from ATCC) were transfected by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method (15). 200 ng pcDNA3-14-3-3 expression plasmid or empty vector pcDNA3, 2 μg 6Myc-tagged ETV1 expression plasmid or empty vector pCS3+-6Myc, and 7 μg pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene) were used for transfection. Coimmunoprecipitations were performed as detailed in Supplementary Methods and described before (19). For coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, ~107 LNCaP (CRL-1740; obtained from ATCC) or PC3 (CRL-1435; obtained from ATCC) cells were employed.

Luciferase assays

293T cells grown in 12-wells were transfected with 200 ng MMP-1 (−525/+15) luciferase reporter plasmid, 150 ng CMV-ETV1 expression plasmid or empty vector pEV3S, and 100 ng pcDNA3 or 100 ng pcDNA3-14-3-3τ. Luciferase activities were determined as described (20).

Retroviral infection

Retrovirus based on pQC vectors or on pSIREN-RetroQ (Clontech) was produced in 293T cells (21). Virus was collected and purified before infection of LNCaP or RWPE-1 (CRL-11609; obtained from ATCC) cells. Sequences targeted by shRNA within ETV1 or 14-3-3τ mRNA were GUGCCUGUACAAUGUCAGU (sh-ETV1#1), UUCGAUGGAGACAUCAAAC (sh-ETV1#5), GUUGCGUGUGGUGAUGAUC (sh-14-3-3τ#1), ACCACGGUGCUGGAAUUGU (sh-14-3-3τ#2) or UCCGGUACCUUGCUGAAGU (sh-14-3-3τ#3).

RT-PCR

293T cells grown in 6-cm dishes were transfected with 0.5 μg CMV-ETV1 expression plasmid or empty vector pEV3S, 200 ng pcDNA3-14-3-3τ and/or 1 μg HER2/Neu-V664E expression plasmid. 36 h after transfection, RNA was isolated employing Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and dissolved in 25 μl H2O, of which 0.1 μl was employed in a 25 μl reaction utilizing the AccessQuick RT-PCR kit (Promega). Details about primers and PCR programs can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Four 10-cm dishes of LNCaP cells were processed for formaldehyde crosslinking and DNA shearing essentially as described (8). Cell lysates were pooled and then split into equal aliquots before adding antibodies. After immunoprecipitation, reverse-crosslinking and DNA recovery, PCR was employed to amplify promoter fragments as detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Cell growth and invasion assays

Cells were seeded in 96-wells. Growth was monitored utilizing the TACS MTT cell proliferation kit (Trevigen). Whereas LNCaP cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, RWPE-1 cells were grown in keratinocyte serum free media (GIBCO) supplemented with 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. For RWPE-1 cell invasion, 5×104 cells were seeded onto a Matrigel invasion chamber (BD Biosciences, 8 μm pores) in keratinocyte serum free media containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and placed into 24-well plates containing normal growth media. After 48 h, non-invaded cells were removed with a cotton swab and invaded cells fixed with methanol and stained with Hemacolor Stain Set (Harleco). For LNCaP cell invasion, 105 cells (pre-treated with 10 μg/ml mitomycin C for 2 h) were seeded onto rat-tail collagen I-coated Boyden chambers (BD Biosciences, 8 μm pores) in DMEM plus 0.1% serum and placed in 24-well plates containing DMEM plus 10% serum.

Immunohistochemical staining

Tissue microarrays (AccuMax A302 (IV)) containing 32 prostate tumors (two sample spots per tumor) and corresponding 32 normal prostate tissues were deparaffinized and then stained with 14-3-3τ (C-17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-732) or 14-3-3ε (8C3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-23957) antibodies. Since normal tissue was lacking in one (14-3-3ε) or two (14-3-3τ) cases, only 31 or 30 pairs, respectively, of tumor/normal tissues were included in the analyses. Cytoplasmic and nuclear immunohistochemical staining was graded on a scale of 0–3. Tumor staining was defined as the average of the staining grade of two sample spots.

Results

Identification of novel ETV1 interaction partners

To identify novel ETV1 cofactors, we fused ETV1 to two affinity tags, expressed it in 293T cells and isolated native protein complexes containing ETV1 by two consecutive affinity purifications. Subsequent mass spectrometry identified six different 14-3-3 proteins (β, γ, ε, η, τ, ζ) that interacted with ETV1 (Supplementary Figure S1).

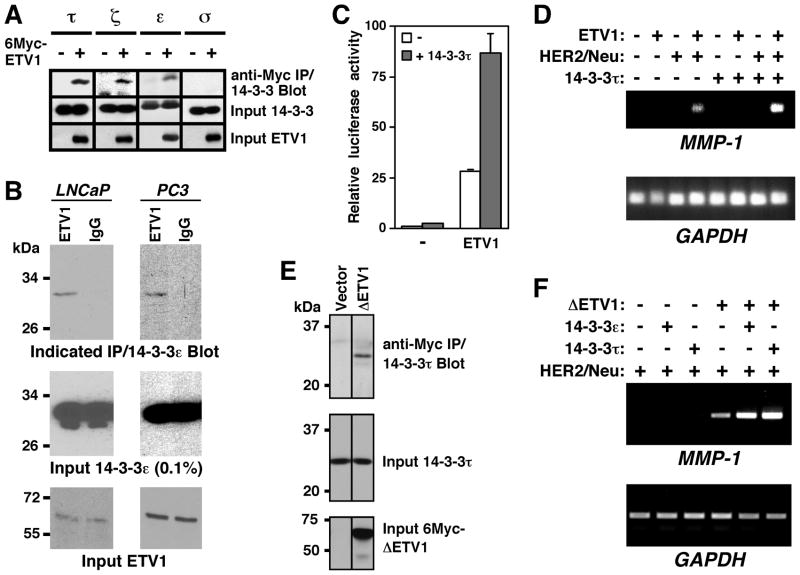

To confirm this interaction with 14-3-3 proteins, we probed their binding to ETV1 in coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Whereas 14-3-3τ, ζ and ε coimmunoprecipitated with ETV1, 14-3-3σ did not (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that ETV1 interacts with all 14-3-3 proteins with the exception of 14-3-3σ. Also, we confirmed the ability of endogenous ETV1 to bind to endogenous 14-3-3ε in two different human prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP and PC3 (Fig. 1B). Consistently, ETV1 also colocalized with 14-3-3τ in LNCaP cell nuclei (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with ETV1. (A) 14-3-3τ, ζ and ε, but not σ, coimmunoprecipitate with ETV1. 6Myc-tagged ETV1 was coexpressed with indicated 14-3-3 proteins in 293T cells. After anti-Myc immunoprecipitation (IP), interacting 14-3-3 proteins were revealed by Western blotting (top). Middle and bottom panels show the presence of 14-3-3 proteins and ETV1, respectively, in the cell extracts. (B) Endogenous coimmunoprecipitation in LNCaP and PC3 prostate cancer cells. After precipitation with ETV1 or control IgG antibodies, coprecipitated 14-3-3ε was detected by Western blotting. (C) Activation of an MMP-1 luciferase reporter construct in 293T cells transfected with ETV1 and/or 14-3-3τ expression plasmids. (D) MMP-1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR analysis of 293T cells transfected with ETV1, HER2/Neu and/or 14-3-3τ. (E) Coimmunoprecipitation of 14-3-3τ with 6Myc-ΔETV1 in 293T cells. (F) Synergy between ΔETV1 and 14-3-3τ/14-3-3ε in inducing MMP-1 transcription in 293T cells.

We next explored whether 14-3-3 proteins would affect transcription of the matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) gene that is targeted by ETV1 (11). First, we analyzed the activation of an MMP-1 luciferase reporter gene in 293T cells. ETV1 strongly stimulated MMP-1 luciferase activity, which was further enhanced by ~3-fold upon coexpression of 14-3-3τ (Fig. 1C). Then, we studied how 14-3-3τ affects endogenous MMP-1 gene transcription in 293T cells. Robust activation of endogenous MMP-1 transcription requires stimulation of ETV1 through the MAPK pathway, which can be accomplished by coexpression of the HER2/Neu receptor tyrosine kinase (11). We did not observe any activation of MMP-1 transcription in the presence of ETV1 or HER2/Neu alone, but their joint expression led to detectable MMP-1 mRNA levels (Fig. 1D). Importantly, 14-3-3τ synergized with ETV1 and HER2/Neu in the activation of MMP-1 transcription; similar results were also observed in case of 14-3-3ε (see Fig. 2D). We conclude that 14-3-3τ and ε stimulate ETV1-dependent gene transcription.

Figure 2.

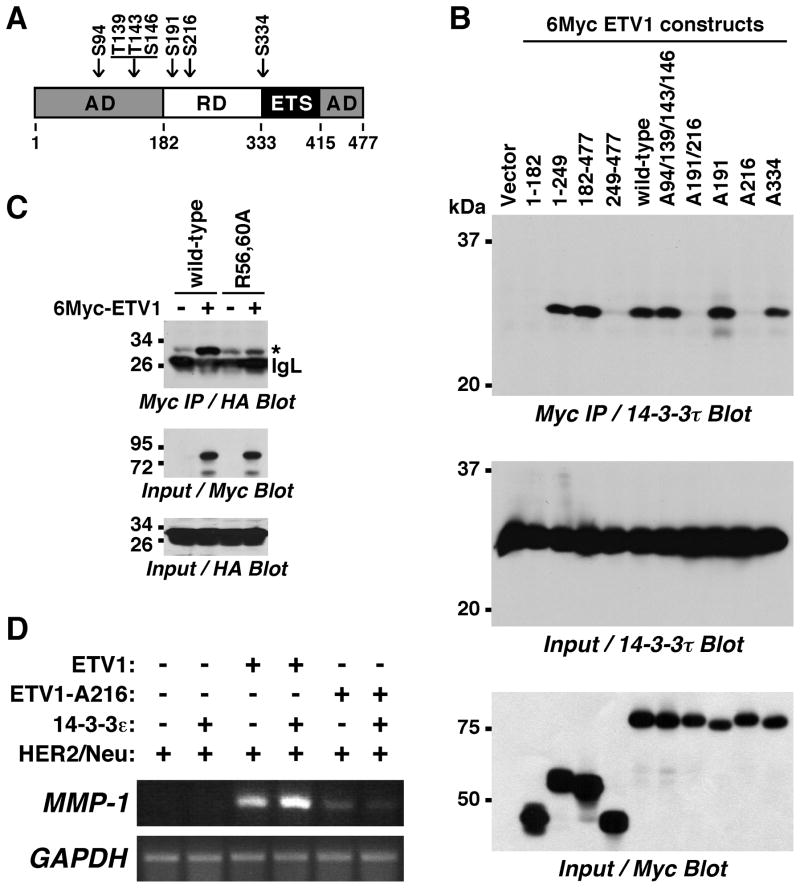

Importance of S216 for the ETV1:14-3-3 interaction. (A) Sketch of ETV1. AD, activation domain; RD, regulatory domain; ETS, DNA-binding domain. Phosphorylation sites for MAPKs (S94, T139, T143, S146) or MAPKAPKs (S191, S216, S334) are pointed out. (B) 6Myc-tagged truncations of ETV1 as well as wild-type or phosphorylation site mutants of full-length 6Myc-ETV1 were coexpressed with 14-3-3τ in 293T cells. After anti-Myc immunoprecipitation, coprecipitated 14-3-3τ was revealed by Western blotting. (C) HA-tagged 14-3-3τ, but not its R56,60A mutant, coimmunoprecipitated with 6Myc-ETV1 in 293T cells. Asterisk marks HA-14-3-3τ that co-migrated with an unspecific band. IgL, immunoglobulin light chain. (D) RT-PCR analysis of 293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids.

Apart from full-length ETV1, splice variants as well as a truncated ETV1 (ΔETV1) were found in prostate tumors. In particular ΔETV1, which lacks the first 131 amino acids due to gene translocation, is frequently overexpressed in prostate cancer (4–6). Therefore, we assessed whether ΔETV1 would also cooperate with 14-3-3 proteins. Indeed, 14-3-3τ coimmunoprecipitated with ΔETV1 (Fig. 1E) and both 14-3-3τ and 14-3-3ε synergized with ΔETV1 to induce MMP-1 transcription (Fig. 1F).

Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between ETV1 and 14-3-3 proteins

14-3-3 proteins often bind phosphoserine-containing motifs (17) and thus potentially also one or more of the seven MAPK-dependent phosphorylation sites within ETV1 (Fig. 2A). To test this, we first delineated the region within ETV1 that mediates interaction with 14-3-3τ. Thus, we expressed ETV1 truncations together with 14-3-3τ and performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 2B). The N-terminal activation domain (amino acids 1–182) did not interact with 14-3-3τ, nor did the C-terminal half of ETV1 (amino acids 249–477). However, amino acids 1–249 and 182–477 interacted, suggesting that amino acids 182–249 are critical for binding to 14-3-3 proteins.

ETV1 amino acids 182–249 contain two MAPKAPK phosphorylation sites, S191 and S216. Therefore, we mutated both S191 and S216 to alanine and noted that the corresponding ETV1-A191/216 molecule was no longer binding to 14-3-3τ (Fig. 2B). Even more, only S216 appears to be important for the binding to 14-3-3τ since the A191 mutant, but not the A216 one, interacted. As a control, neither mutation of all four MAPK sites (A94/139/143/146) nor of another MAPKAPK site (A334) affected ETV1 binding to 14-3-3τ; please note that ETV1 is phosphorylated on S191 and S216 due to constitutive MAPKAPK activity in 293T cells (13, 14). These data indicate that 14-3-3τ interacts with ETV1 via phosphorylated S216.

To further corroborate this notion, we mutated 14-3-3τ at two conserved arginine residues (R56 and R60) that are crucial for binding of 14-3-3 proteins to phosphorylated ligands (22). Indeed, whereas wild-type 14-3-3τ coimmunoprecipitated strongly with ETV1, the R56,60A mutant did not (Fig. 2C), further implicating that the interaction between 14-3-3τ and ETV1 is mediated by phosphorylation on S216.

We then assessed how mutation of S216 would affect the ability of ETV1 to activate MMP-1 transcription in 293T cells. In contrast to wild-type ETV1, the A216 mutant was less capable of stimulating endogenous MMP-1 transcription in cooperation with HER2/Neu (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, whereas wild-type ETV1 synergized with 14-3-3ε, no such cooperation was observable for the A216 mutant. Altogether, these data indicate that MAPKAPK-mediated phosphorylation on S216 is required for ETV1’s ability to cooperate with 14-3-3 proteins.

Relationship between ETV1 and 14-3-3 proteins in prostate cancer cells

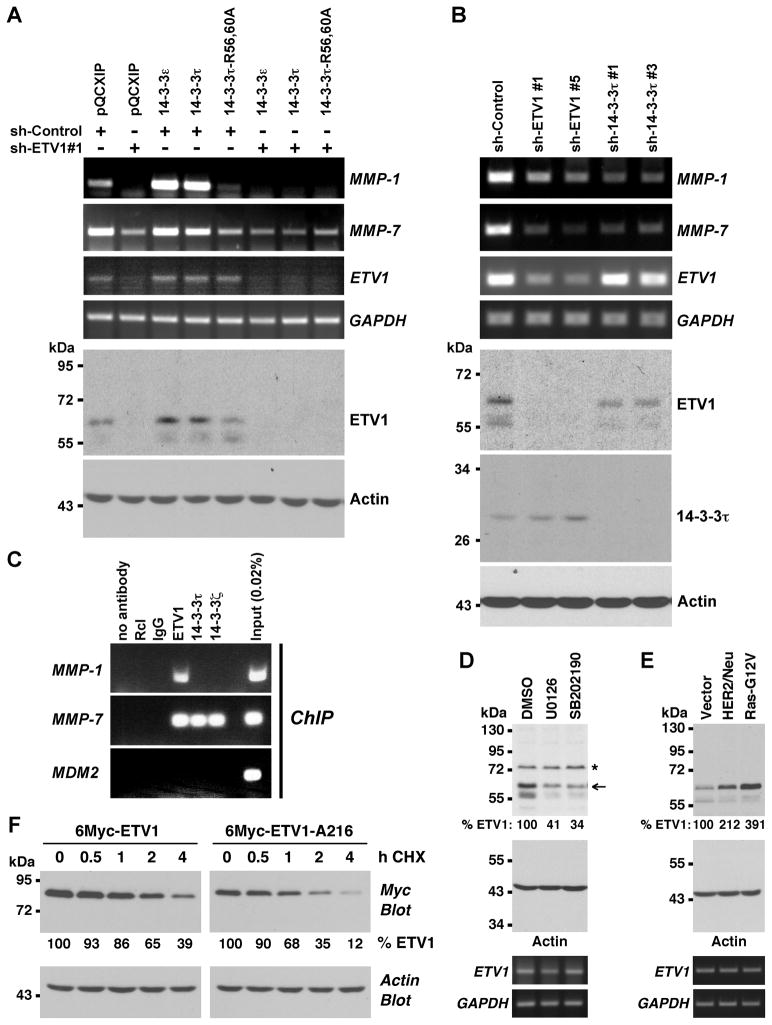

The most recognized pathological role of ETV1 is in prostate cancer (2). Therefore, we assessed whether 14-3-3 proteins also cooperate with ETV1 in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. To this end, we studied the expression of ETV1 target genes by RT-PCR. Retroviral delivery of ETV1 shRNA expectedly reduced MMP-1 transcription (Fig. 3A). Importantly, retroviral overexpression of either 14-3-3ε or 14-3-3τ resulted in enhanced MMP-1 mRNA levels (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 14-3-3ε or τ had negligible impact on MMP-1 transcription in the presence of ETV1 shRNA, indicating that 14-3-3 proteins act in an ETV1-dependent manner to stimulate MMP-1 transcription. Consistently, the R56,60A mutant of 14-3-3τ that does not interact with ETV1 was unable to cooperate with ETV1; it even reduced MMP-1 transcription, likely due to its ability to act as a dominant-negative molecule (22).

Figure 3.

14-3-3 proteins affect ETV1 activity and stability in prostate cancer cells. (A) LNCaP cells were infected with retrovirus expressing control shRNA or ETV1 shRNA. In addition, cells were infected with retrovirus expressing indicated 14-3-3 proteins or empty vector pQCXIP. MMP-1, MMP-7, ETV1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were assessed by RT-PCR. The bottom two panels show Western blots of ETV1 or actin. (B) Similar analysis of LNCaP cells infected with retrovirus encoding ETV1 or 14-3-3τ shRNAs. (C) ChIP assays in LNCaP cells utilizing indicated antibodies for precipitation. MMP-1 and MMP-7 promoter regions encompassing ETV1 binding sites were amplified, as was the control MDM2 promoter. Rcl antibodies, IgG and no antibody served as negative controls. (D) LNCaP cells were treated with 10 μM U0126 or 5 μM SB202190 24 h and 12 h before lysis and ETV1 levels (normalized to actin) determined by Western blotting. Asterisk marks an unspecific band and arrow points at ETV1. Bottom two panels show corresponding RT-PCR measurements of ETV1 and GAPDH mRNA. (E) Retrovirus encoding HER2/Neu or Ras-G12V was employed to infect LNCaP cells and ETV1 protein and mRNA levels were determined. (F) 6Myc-tagged ETV1 or its A216 mutant was expressed in LNCaP cells. Protein synthesis was then inhibited with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) and ETV1 protein levels measured for up to 4 h after the addition of CHX by anti-Myc Western blotting. Relative ETV1 protein amount normalized to actin is indicated.

We also studied another target gene of ETV1, the matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) (21). Downregulation of ETV1 reduced MMP-7 gene transcription, but overexpression of 14-3-3ε or τ did not significantly stimulate MMP-7 transcription (Fig. 3A). This could be due to the fact that endogenous 14-3-3 protein levels were sufficient to maximally cooperate with ETV1 in MMP-7 transcription. If so, interfering with endogenous 14-3-3 proteins should result in a reduction of MMP-7 mRNA levels. And indeed, expression of dominant-negative 14-3-3τ-R56,60A suppressed MMP-7 gene transcription (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, we analyzed how downregulation of 14-3-3τ would affect MMP-1 and MMP-7 transcription in LNCaP cells. Similar to downregulation of ETV1, two different 14-3-3τ shRNAs caused decreased MMP-1 and MMP-7 mRNA levels (Fig. 3B), consistent with 14-3-3τ being an important interactant of ETV1.

Next, we assessed whether 14-3-3 proteins would bind together with ETV1 to target gene promoters in ChIP assays. Surprisingly, 14-3-3 proteins displayed a promoter-specific behavior. Whereas ETV1 bound to both the MMP-1 and MMP-7 promoter, only the MMP-7 promoter was occupied by 14-3-3 proteins (Fig. 3C). This implies that 14-3-3 proteins indirectly stimulate ETV1-mediated MMP-1 upregulation.

A hint how this may occur came from the analysis of ETV1 proteins levels upon 14-3-3 overexpression and downregulation. When overexpressing 14-3-3 proteins in LNCaP cells, we observed that ETV1 mRNA levels were essentially unaffected, but ETV1 protein levels increased (see Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure S3A). Conversely, when downregulating 14-3-3τ, ETV1 protein but not mRNA levels decreased (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Figure S3B). These data suggest that the ETV1 protein is stabilized through its interaction with 14-3-3 proteins.

To investigate this in more detail, we analyzed if ETV1 protein levels change when S216 phosphorylation is reduced by blocking MAPK signaling in LNCaP cells. Suppressing ERK MAPK activation with U0126 (which blocks RSK1 and MSK activation) as well as inhibiting p38 MAPKs (which are activators of MSKs) with SB202190 reduced ETV1 protein levels, whereas ETV1 mRNA levels were basically unaffected (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Figure S3C). Conversely, overexpression of HER2/Neu or Ras-G12V, which induces the phosphorylation of ETV1 (11), increased ETV1 protein but not mRNA levels (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Figure S3D). Lastly, we compared the stability of wild-type ETV1 and its A216 mutant in LNCaP cells treated with cycloheximide that blocks de novo protein synthesis. We observed that ETV1’s stability decreased upon mutation of S216 (Fig. 3F); the calculated half-lives of wild-type and A216 ETV1 were 3.1 h and 1.6 h, respectively. Collectively, these data indicate that the interaction of phosphorylated S216 with 14-3-3 proteins is a crucial determinant of ETV1 protein stability.

Physiological role of the ETV1:14-3-3 interaction

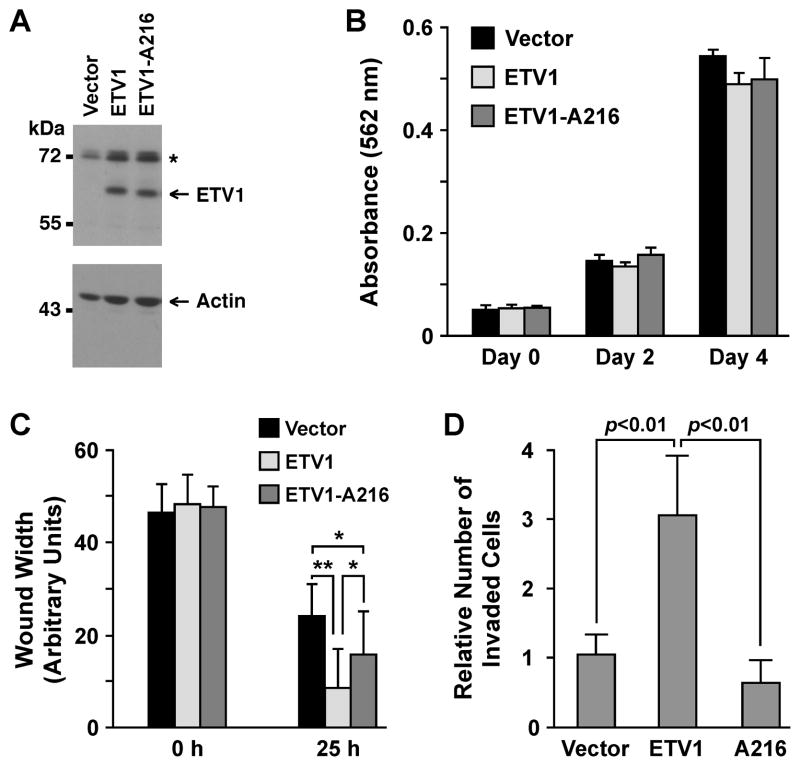

Next, we analyzed how S216 phosphorylation may affect non-transformed, benign RWPE-1 prostate epithelial cells. To this end, we overexpressed wild-type ETV1 or its A216 mutant at comparable levels (Fig. 4A). Neither wild-type nor mutated ETV1 affected the growth of RWPE-1 cells (Fig. 4B). However, ETV1 reportedly stimulates prostate cell migration and invasion (5, 7, 21). Accordingly, ETV1 overexpression led to faster wound closure and increased invasion through matrigel (Fig. 4C and D and Supplementary Figure S4). In contrast, the A216 mutant was less able to promote migration (Fig. 4C) or not at all invasion (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that S216 phosphorylation, and by inference the interaction with 14-3-3 proteins, is important for ETV1’s ability to stimulate cell migration and invasion.

Figure 4.

Impact of the S216 residue in RWPE-1 cells. (A) Western blots of RWPE-1 cells stably expressing wild-type ETV1 or its A216 mutant. Asterisk marks an unspecific band. (B) Growth assay. (C) Confluent RWPE-1 cells were scraped with a pipet tip. Wound width at 0 h and 25 h was measured. *: p<0.01; **: p<0.001. (D) Invasion of RWPE-1 cells through matrigel.

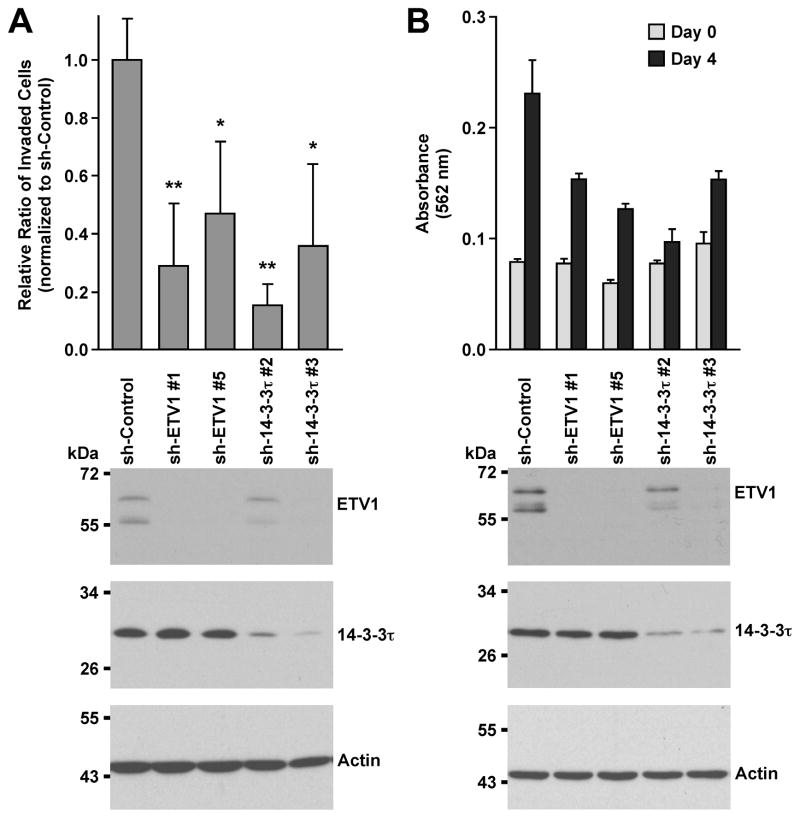

Then, we compared the physiological functions of 14-3-3τ and ETV1 in LNCaP cells. We reasoned that if an ETV1:14-3-3τ complex is relevant in these cancer cells, elimination of either component of this complex should show the same effect. And indeed, two different 14-3-3τ shRNAs phenocopied the reduction of cell invasion upon ETV1 downregulation (Fig. 5A). Likewise, downregulation of either ETV1 or 14-3-3τ with two different shRNAs resulted in significantly delayed cell growth (Fig. 5B). Altogether, these results strongly suggest that 14-3-3 proteins are crucial for ETV1’s function in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Analysis of LNCaP cell physiology. (A) Cells were infected with retrovirus expressing indicated shRNA and selected in puromycin. Thereafter, cell invasion through collagen was measured. Bottom panels show Western blots for ETV1, 14-3-3τ and actin. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01. (B) Cells were twice infected with retrovirus expressing ETV1 or 14-3-3τ shRNA and then seeded for growth assays two days later. Growth was significantly reduced (p<0.05) by all shRNAs employed compared to sh-Control.

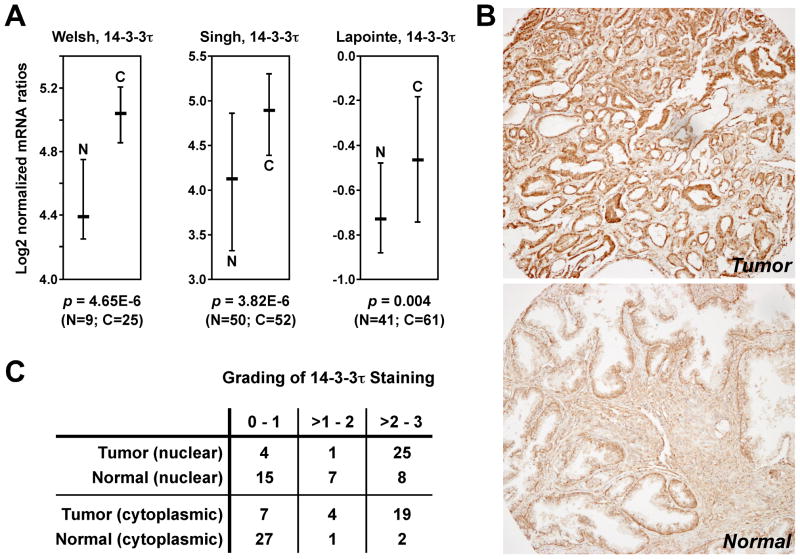

Overexpression of 14-3-3 proteins in prostate tumors

To our knowledge, the expression of non-σ 14-3-3 proteins has not been studied in human prostate tumor samples. Therefore, we analyzed publicly available microarray data (23–25) for the expression of 14-3-3τ mRNA. As shown in Fig. 6A, 14-3-3τ mRNA was significantly overexpressed in prostate tumors compared to normal tissues in three different data sets. Furthermore, we stained 30 matching pairs of prostate tumors and normal tissues with 14-3-3τ antibodies (Fig. 6B). Supplementary Figure S5 corroborates the specificity of the utilized 14-3-3τ antibody. We found that 14-3-3τ staining was significantly (Wilcoxon signed-rank test; p<0.001) enhanced both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of prostate tumor cells (Fig. 6C). Similar results were obtained for 14-3-3ε overexpression at the mRNA and protein level (Supplementary Figure S6). Taken together, these data suggest that many prostate tumors are characterized by overexpression of non-σ 14-3-3 proteins.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of 14-3-3τ in prostate tumors. (A) Analysis of publicly available microarray data (23–25) through the Oncomine webtool. Shown are log2 median-centered ratios of 14-3-3τ mRNA levels with the median and 25–75 percentile range. N denotes normal prostate tissue, C prostate carcinoma. Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of 14-3-3τ expression in 30 pairs of human prostate tumors and matching normal tissues. Shown is a representative pair of tumor (top) and normal (bottom) tissue. Brown staining indicates the presence of 14-3-3τ, whereas blue color represents hematoxylin counter-staining. (C) Grading of 14-3-3τ protein expression in the cytoplasm and nucleus of 30 matching prostate tumors and normal tissues.

Discussion

In this report, we identified non-σ 14-3-3 proteins as novel interaction partners of ETV1 and ΔETV1, thereby increasing the understanding about the ETV1/ΔETV1 oncoproteins and also shedding new light on the function of non-σ 14-3-3 proteins. Interestingly, while ETV1 and ΔETV1 both stimulated migration and invasion of benign PNT2C2 prostate cells, only ETV1 was capable of inducing anchorage-independent cell growth. Moreover, ETV1 was more active than ΔETV1 when tested with a luciferase reporter gene assay in PNT2C2 cells (5, 6). However, we found that both ETV1 and ΔETV1 synergized with 14-3-3τ or 14-3-3ε in stimulating endogenous MMP-1 transcription in 293T cells, suggesting that the aforementioned differences between ETV1 and ΔETV1 were not a reflection of different abilities to interact with 14-3-3 proteins.

Phosphorylation of ETV1 is a crucial means to regulate its function (9). However, the mechanism by which MAPK-dependent phosphorylation does so has remained unresolved. Here, we show that phosphorylation on S216 facilitates the interaction of ETV1 with non-σ 14-3-3 proteins. S216 is phosphorylated by MAPKAPKs such as RSK1, MSK1 or MSK2 (12, 13) and both RSK1 (26) and MSK2 (Supplementary Figure S7) are overexpressed in prostate tumors, suggesting that ETV1 phosphorylation on S216 is enhanced in prostate cancer.

RSK1 and MSKs are activated by MAPKs, whose activity is increased in the majority of prostate tumors. Mostly, this is due to mutations and/or gene overexpression in the HER2/Neu→Ras→Raf→MEK→MAPK→MAPKAPK pathway. In fact, ~40% of primary and ~90% of metastatic prostate tumors display hyperactivation of Ras and Raf oncoproteins (27, 28) and HER2/Neu is also overexpressed in many prostate tumors (29). Accordingly, even if RSK1 and MSKs were not overexpressed in prostate tumors, their activity and hence S216 phosphorylation on ETV1 can still be enhanced due to MAPK pathway hyperactivation.

Posttranslational modification of S216 exerts a great impact on ETV1 function. First, ETV1-dependent MMP-1 transcription was reduced upon mutation of S216 to alanine; moreover, while 14-3-3τ and 14-3-3ε synergized with ETV1 in inducing MMP-1 transcription, no such cooperation was observable with ETV1-A216. Second, mutation of S216 reduced the ability of ETV1 to stimulate RWPE-1 cell migration and invasion. Third, the half-life of the A216 mutant was reduced by half compared to wild-type ETV1, implicating that interaction of ETV1 with 14-3-3 proteins antagonizes ETV1 destruction. Since ETV1 can be targeted by COP1 to the proteasomal pathway (30), 14-3-3 proteins may preclude COP1 or other E3 ubiquitin ligases from targeting ETV1 to the proteasome. Such a scenario is not unprecedented. For instance, 14-3-3σ interacts with the p53 tumor suppressor and prevents its ubiquitination by MDM2, thereby also increasing p53-dependent gene transcription (31). Interestingly, 14-3-3 proteins sequester many nuclear proteins upon phosphorylation to the cytoplasm (17, 18). However, ETV1 appears to be a constitutively nuclear protein in LNCaP (Supplementary Figure S2) and other cell lines (9, 14), indicating that non-σ 14-3-3 proteins do not regulate ETV1 by affecting its intracellular localization.

Whereas 14-3-3 proteins bound to the same MMP-7 promoter region as ETV1, we did not find binding of 14-3-3 proteins to the MMP-1 promoter, indicating that ETV1 does not necessarily associate with 14-3-3 proteins at gene promoters. But if so, as in case of the MMP-7 promoter, one way how 14-3-3 proteins might facilitate gene transcription is by binding to phosphorylated S10 on histone H3, which could lead to reduced heterochromatin binding protein-1 interaction and thus enhanced gene transcription (32). Due to the fact that 14-3-3 proteins dimerize and are therefore bivalent (17), it is possible that a monomeric ETV1 molecule recruits a 14-3-3 dimer that simultaneously binds to phosphorylated S10 on histone H3. Notably, this serine residue is also phosphorylated by MSK1 and MSK2 (33), outlining another way how MSKs contribute to ETV1-dependent transcription.

Aside from prostate cancer, ETV1 has oncogenic properties in melanomas where it is overexpressed in 40% of all cases (3). In part, this overexpression might be a consequence of enhanced S216 phosphorylation, since constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway by the BRAF-V600E mutation is prevalent in skin tumors. Our results also provide an explanation why the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, which is another upstream activator of the MAPK pathway, may lead to the reported increase of ETV1 stability in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (34). Thus, ETV1 stabilization through S216 phosphorylation may contribute to the development of many different tumors.

A recent report demonstrated that 48 signature genes, including ETV1, were upregulated through the MAPK pathway in melanoma cell lines expressing BRAF-V600E (35). However, the same report also showed that ETV1 mRNA levels were not affected by MEK inhibition in other cancer cells characterized by amplified/mutated HER2/Neu or EGFR. Likewise, inhibiting KIT with imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells (34) or blocking the MAPK pathway with U0126 or SB202190 in LNCaP prostate cancer cells (Fig. 3D) did not affect ETV1 mRNA levels, whereas ETV1 protein levels were reduced. On the other hand, activation of the MAPK pathway upon overexpression of HER2/Neu or Ras-G12V increased ETV1 protein but not ETV1 mRNA levels in LNCaP cells (Fig. 3E); similarly, ETV1 transcription was unaffected in PC3 prostate cancer cells upon HER2/Neu or Ras-G12V overexpression (Supplementary Figure S3E). These data suggest that MAPK-dependent ETV1 overexpression in melanomas is due to both increased ETV1 transcription and enhanced ETV1 stability caused by its interaction with non-σ 14-3-3 proteins, but only due to the latter in prostate and many other tumors.

The role of 14-3-3 proteins in cancer is still a matter of debate. On one side, 14-3-3σ is thought to be a tumor suppressor. Consistently, loss of 14-3-3σ expression caused by epigenetic silencing is often observed in various tumors (17, 18), including prostate tumors and its precursors (36, 37). Notably, while we found all six non-σ 14-3-3 proteins in ETV1 complexes, we were unable to detect an interaction between 14-3-3σ and ETV1. Possibly, this is due to the divergent structure of 14-3-3σ (17).

To our knowledge, the expression and importance of non-σ 14-3-3 proteins in prostate tumors has remained unexplored. Our data demonstrate that both 14-3-3τ and 14-3-3ε are overexpressed in prostate tumors. Moreover, we found evidence that 14-3-3ζ, γ and β are also upregulated in prostate cancer (Supplementary Figure S8). Furthermore, 22 out of 30 prostate tumors studied in our report displayed overexpression of at least one (τ or ε) of the two 14-3-3 proteins analyzed, indicating that probably the vast majority of prostate tumors overexpresses one or more of the six non-σ 14-3-3 protein. Thus, ETV1 overexpression will most often be accompanied by non-σ 14-3-3 overexpression, providing these proteins an opportunity to cooperatively contribute to the causation of prostate cancer. Similar to prostate tumors, overexpression of non-σ 14-3-3 proteins may promote neoplastic transformation in other organs. For instance, 14-3-3ζ overexpression was observed in HER2/Neu-positive breast tumors and correlated with reduced survival (38); given that ETV1 is overexpressed in HER2/Neu-positive breast tumors (2), this suggests a potential cooperation of 14-3-3ζ with ETV1 in this cancer.

Downregulation of 14-3-3τ in LNCaP prostate cancer cells reduced their growth and invasion. In part, this may be explained by the ability of 14-3-3τ to stimulate ETV1 target genes such as MMP-1 and MMP-7. MMPs have emerged as crucial modulators of tumorigenesis and are not only involved in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix, but have a plethora of other functions, including the processing and shedding of growth factors and cytokines as well as regulating angiogenesis (39). In particular, MMP-1 is often overexpressed in prostate tumors and it promoted the ability of prostate cancer cells to migrate and invade in vitro and grow tumors and metastasize in an orthotopic mouse tumor model (40, 41). Likewise, MMP-1 is overexpressed in melanomas and correlates with reduced patient survival (42). Notably, MMP-1 overexpression conferred an invasive and metastatic phenotype on early stage melanoma cells, whereas MMP-1 downregulation in late stage melanoma cells curtailed metastasis and angiogenesis (43, 44). Similarly, MMP-7 overexpression is often found in prostate and skin cancer (45–47) and may promote tumorigenesis by enhancing invasion, metastasis and cell proliferation (48–50).

In conclusion, non-σ 14-3-3 proteins may cooperate with ETV1 not only in prostate tumors, but also in various other neoplasias including melanomas and HER2/Neu-positive breast tumors. Accordingly, obstructing the interaction of ETV1 with non-σ 14-3-3 proteins may be a worthwhile adjuvant therapy in these cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Madden for performing mass spectrometry and Jaehwa Choi for help with statistical analysis.

Grant Support

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-08-1-0177) and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA154745). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the granting agencies.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hollenhorst PC, McIntosh LP, Graves BJ. Genomic and biochemical insights into the specificity of ETS transcription factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:437–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.79.081507.103945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh S, Shin S, Janknecht R. ETV1, 4 and 5: An oncogenic subfamily of ETS transcription factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jane-Valbuena J, Widlund HR, Perner S, Johnson LA, Dibner AC, Lin WM, et al. An oncogenic role for ETV1 in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2075–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans KG, van der Korput HA, van Marion R, van de Wijngaart DJ, Ziel-van der Made A, Dits NF, et al. Truncated ETV1, fused to novel tissue-specific genes, and full-length ETV1 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7541–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasi D, van der Korput HA, Douben HC, de Klein A, de Ridder CM, van Weerden WM, et al. Overexpression of full-length ETV1 transcripts in clinical prostate cancer due to gene translocation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomlins SA, Laxman B, Dhanasekaran SM, Helgeson BE, Cao X, Morris DS, et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature. 2007;448:595–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin S, Kim TD, Jin F, van Deursen JM, Dehm SM, Tindall DJ, et al. Induction of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and modulation of androgen receptor by ETS variant 1/ETS-related protein 81. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8102–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janknecht R. Analysis of the ERK-stimulated ETS transcription factor ER81. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1550–6. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowdy SC, Mariani A, Janknecht R. HER2/Neu- and TAK1-mediated up-regulation of the transforming growth factor beta inhibitor Smad7 via the ETS protein ER81. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44377–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosc DG, Goueli BS, Janknecht R. HER2/Neu-mediated activation of the ETS transcription factor ER81 and its target gene MMP-1. Oncogene. 2001;20:6215–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Janknecht R. Regulation of the ETS transcription factor ER81 by the 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase 1 and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42669–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janknecht R. Regulation of the ER81 transcription factor and its coactivators by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) Oncogene. 2003;22:746–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papoutsopoulou S, Janknecht R. Phosphorylation of ETS transcription factor ER81 in a complex with its coactivators CREB-binding protein and p300. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7300–10. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7300-7310.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel A, Janknecht R. Acetylation-mediated transcriptional activation of the ETS protein ER81 by p300, P/CAF, and HER2/Neu. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6243–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6243-6254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goel A, Janknecht R. Concerted activation of ETS protein ER81 by p160 coactivators, the acetyltransferase p300 and the receptor tyrosine kinase HER2/Neu. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14909–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison DK. The 14-3-3 proteins: integrators of diverse signaling cues that impact cell fate and cancer development. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardino AK, Yaffe MB. 14-3-3 proteins as signaling integration points for cell cycle control and apoptosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:688–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knebel J, De Haro L, Janknecht R. Repression of transcription by TSGA/Jmjd1a, a novel interaction partner of the ETS protein ER71. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:319–29. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiTacchio L, Bowles J, Shin S, Lim DS, Koopman P, Janknecht R. Transcription factors ER71/ETV2 and SOX9 participate in a positive feedback loop in fetal and adult mouse testis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23657–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin S, Oh S, An S, Janknecht R. ETS variant 1 regulates matrix metalloproteinase-7 transcription in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:306–14. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorson JA, Yu LW, Hsu AL, Shih NY, Graves PR, Tanner JW, et al. 14-3-3 proteins are required for maintenance of Raf-1 phosphorylation and kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5229–38. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh JB, Sapinoso LM, Su AI, Kern SG, Wang-Rodriguez J, Moskaluk CA, et al. Analysis of gene expression identifies candidate markers and pharmacological targets in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5974–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh D, Febbo PG, Ross K, Jackson DG, Manola J, Ladd C, et al. Gene expression correlates of clinical prostate cancer behavior. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:203–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapointe J, Li C, Higgins JP, van de Rijn M, Bair E, Montgomery K, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark DE, Errington TM, Smith JA, Frierson HF, Jr, Weber MJ, Lannigan DA. The serine/threonine protein kinase, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase, is an important regulator of prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3108–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palanisamy N, Ateeq B, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Pflueger D, Ramnarayanan K, Shankar S, et al. Rearrangements of the RAF kinase pathway in prostate cancer, gastric cancer and melanoma. Nat Med. 2010;16:793–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Signoretti S, Montironi R, Manola J, Altimari A, Tam C, Bubley G, et al. Her-2-neu expression and progression toward androgen independence in human prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1918–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baert JL, Monte D, Verreman K, Degerny C, Coutte L, de Launoit Y. The E3 ubiquitin ligase complex component COP1 regulates PEA3 group member stability and transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2010;29:1810–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang HY, Wen YY, Chen CH, Lozano G, Lee MH. 14-3-3 sigma positively regulates p53 and suppresses tumor growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7096–107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7096-7107.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter S, Simboeck E, Fischle W, Zupkovitz G, Dohnal I, Mechtler K, et al. 14-3-3 proteins recognize a histone code at histone H3 and are required for transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 2008;27:88–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soloaga A, Thomson S, Wiggin GR, Rampersaud N, Dyson MH, Hazzalin CA, et al. MSK2 and MSK1 mediate the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 and HMG-14. EMBO J. 2003;22:2788–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chi P, Chen Y, Zhang L, Guo X, Wongvipat J, Shamu T, et al. ETV1 is a lineage survival factor that cooperates with KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Nature. 2010;467:849–53. doi: 10.1038/nature09409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Ye Q, Viale A, Sander C, Solit DB, et al. (V600E)BRAF is associated with disabled feedback inhibition of RAF-MEK signaling and elevated transcriptional output of the pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4519–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900780106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng L, Pan CX, Zhang JT, Zhang S, Kinch MS, Li L, et al. Loss of 14-3-3sigma in prostate cancer and its precursors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3064–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lodygin D, Diebold J, Hermeking H. Prostate cancer is characterized by epigenetic silencing of 14-3-3sigma expression. Oncogene. 2004;23:9034–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu J, Guo H, Treekitkarnmongkol W, Li P, Zhang J, Shi B, et al. 14-3-3zeta Cooperates with ErbB2 to promote ductal carcinoma in situ progression to invasive breast cancer by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker T, Tickle S, Wasan H, Docherty A, Isenberg D, Waxman J. Serum metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: markers for malignant potential. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:506–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pulukuri SM, Rao JS. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 promotes prostate tumor growth and metastasis. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:757–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikkola J, Vihinen P, Vlaykova T, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Kahari VM, Pyrhonen S. High expression levels of collagenase-1 and stromelysin-1 correlate with shorter disease-free survival in human metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:432–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blackburn JS, Rhodes CH, Coon CI, Brinckerhoff CE. RNA interference inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-1 prevents melanoma metastasis by reducing tumor collagenase activity and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10849–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blackburn JS, Liu I, Coon CI, Brinckerhoff CE. A matrix metalloproteinase-1/protease activated receptor-1 signaling axis promotes melanoma invasion and metastasis. Oncogene. 2009;28:4237–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pajouh MS, Nagle RB, Breathnach R, Finch JS, Brawer MK, Bowden GT. Expression of metalloproteinase genes in human prostate cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:144–50. doi: 10.1007/BF01613138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto K, Kihira Y, Matuo Y, Usui T. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in human prostate. J Urol. 1998;160:1872–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawasaki K, Kawakami T, Watabe H, Itoh F, Mizoguchi M, Soma Y. Expression of matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) in primary cutaneous and metastatic melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:613–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell WC, Knox JD, Navre M, Grogan TM, Kittelson J, Nagle RB, et al. Expression of the metalloproteinase matrilysin in DU-145 cells increases their invasive potential in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res. 1993;53:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch CC, Hikosaka A, Acuff HB, Martin MD, Kawai N, Singh RK, et al. MMP-7 promotes prostate cancer-induced osteolysis via the solubilization of RANKL. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:485–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kivisaari AK, Kallajoki M, Ala-aho R, McGrath JA, Bauer JW, Konigova R, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 activates heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:726–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.