Esophageal variceal hemorrhage is responsible for 70% of all upper gastrointestinal bleeding presentations in patients with portal hypertension secondary to liver cirrhosis.[1] Currently, the combination of basic resuscitation, vasoactive drugs, antibiotics and endoscopic band ligation are accepted as the optimal management for patients with acute variceal bleeding.[2] However, despite these therapies, the 6-week mortality rate due to variceal bleeding is extremely high at 20%.[3] In the acute setting, endoscopic visualization is often hampered by blood and this may lead to failure to control bleeding or early re-bleeding in 10-20% of patients.[4] These patients are then usually treated with salvage therapies, such as balloon tamponade, insertion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), surgery (e.g., laparoscopic azygoportal vein disconnection) and more recently insertion of self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS).

Balloon tamponade should only be used when endoscopy fails. Hemostasis is achieved by direct compression of the bleeding varices and is effective in 80% of cases.[5] However, it is not recommended for use for more than 24 h and is associated with fatal complications in up to 20% of cases.[5] When the balloon is in situ the patients cannot eat, are required to be intubated and repeat endoscopy is not possible. When the balloon is deflated, re-bleeding occurs in over 50% of cases.[6] Therefore, it should only be used in massive uncontrolled bleeding and as a temporary bridge to another definitive therapy such as TIPS.

TIPS is an intrahepatic shunt that connects the portal vein to the hepatic vein via a metallic stent that is usually 8 mm to 12 mm in diameter. It is tremendously effective with initial hemostasis achieved in 95% of patients and re-bleeding occurring in 18%.[7] However, TIPS is technically challenging, often not readily available, and is associated with a mortality rate of approximately 50% at 1 year.[8] In addition, it carries a significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy and is contraindicated in patients with significant cholestasis, advanced renal or cardiac disease. The search for a more readily available and simpler treatment has led to the use of covered SEMS for the treatment of refractory esophageal variceal hemorrhage.

Traditionally, SEMS have been used for a variety of benign and malignant esophageal disorders. Recently, a specially designed removable covered SEMS (SX-Ella stent Danis; Ella-CS, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic) for the treatment of esophageal variceal hemorrhage has become available. This nitinol stent is 135 mm in length and 25mm in diameter, and achieves hemostasis by direct compression of esophageal varices. The stent can be deployed in the lower esophagus over a guide wire without any radiological assistance as the delivery apparatus has a built-in gastric balloon, which is used to guide stent placement. The endoscope is re-inserted after stent placement to confirm its position and efficacy in achieving hemostasis. Retrieval of the stent is recommended within 7 days to avoid development of pressure induced ulceration of the esophageal wall.[9] After stent placement, oral intake and hence nutrition can be maintained, which can allow sufficient time for improvement in liver function and ultimately the opportunity to bridge to a more durable therapy (TIPS, orthotopic liver transplant).

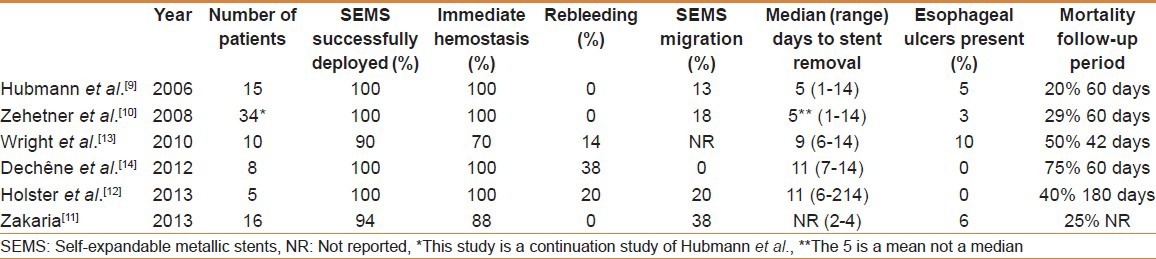

A total of 5 studies have reported on the use of the SX-Ella stent Danis as salvage therapy for patients with ongoing variceal bleeding [Table 1]. The initial pilot study conducted by Hubmann et al.[9] reported on 20 patients with refractory esophageal variceal bleeding despite endoscopic therapy or balloon tamponade. Of the 20 patients, 5 had standard SEMS inserted. The SX-Ella stent Danis was used in the remaining 15 patients and was successfully deployed in all with immediate hemostasis achieved in 100%. After 2 years, the same group published their extended series of 39 patients who presented similarly with nearly identical results.[10]

Table 1.

Published series using SX-Ella stent Danis for esophageal variceal hemorrhage

To date, all reported studies have assessed the use of SEMS for esophageal variceal bleeding refractory to standard medical and endoscopic therapy. However, in this issue of The Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology, Zakaria et al.[11] present a case series describing the use of the SX-Ella stent Danis for the initial control of active esophageal variceal hemorrhage at a single center in Egypt. This is the first study to assess the use of SEMS as primary therapy for acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage. A total of 16 patients with hepatitis C related cirrhosis were included, with the majority (14/16) having Child B or C cirrhosis. SEMS were successfully deployed in 15/16 (94%) patients with a mean procedure time of 10 min. One technical failure occurred due to malfunction of the delivery system that led to rupture of the gastric balloon. Immediate hemostasis was achieved in 14 of the remaining patients. Failure to achieve hemostasis occurred in one patient as the bleeding originated from a gastric varix. This is an expected occurrence as placement of esophageal stents does not offer tamponade of gastric varices. Persistent variceal bleeding after stent placement should raise the suspicion for bleeding gastric varices. In this study, despite the endoscope being able to pass through the stent into the stomach and visualize the gastric varix, hemostasis could not be achieved and the patient died from exsanguination.

The overall mortality was 4/16 (25%) though only 1 patient died directly from exsanguination. The study does not comment on the duration of follow-up, but mortality appears to compare favorably with results from published literature where the mortality at 60 days ranged between 20% and 75% [Table 1]. Other expected clinically significant adverse outcomes were stent migration and esophageal ulceration. Stent migration occurred in 6 (38%) patients despite endoscopic re-inspection being delayed by 3 min to allow the stent adequate time to expand. This figure is in line with published data revealing a high rate of stent migration between 0% and 38% [Table 1]. This is not unexpected in these patients as there is no stricture maintaining the covered stent in position. In addition, covered stents do not embed into the esophageal mucosa. In this and other published studies,[9,10] stent migration did not appear to result in re-bleeding and was identified during planned endoscopic stent removal in the majority of patients.

Concerns regarding esophageal injury (ulceration and perforation) are the reason for the recommended 7 day duration of stent insertion. Esophageal ulceration occurred in 6% of patients in this study, which is also in line with the rate reported in other studies [Table 1]. Recently, Holster et al.[12] challenged the need for stent removal and reported on five patients who were felt to be unsuitable for TIPS at the time of uncontrollable esophageal variceal bleeding. In these patients, the SEMS was placed with the intent of it being definitive therapy rather than as a bridge to an alternative treatment. In this small series, stents were removed in two patients after > 14 days and remained in situ until death in the remaining three patients (6-214 days). No complications related to the longer duration of SEMS insertion were observed.

Endoscopic band ligation is the treatment of choice for patients with acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage due to its wide availability, efficacy, safety and ease of use. SEMS; however, appear to be more effective, easier to insert and likely associated with a lower risk of complications compared to balloon tamponade in the treatment of patients with refractory bleeding. Zakaria et al.[11] have provided data to indicate that SEMS may be effective as initial therapy for patients with esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Larger studies with long-term follow-up are needed to further study efficacy, safety, and re-bleeding rates of such an approach. For the time being, SEMS should be primarily considered as salvage therapy when endoscopic band ligation and sclerotherapy fail. To investigate this further, a UK-based multicenter randomized trial comparing SEMS and standard endoscopic therapy in acute esophageal variceal bleeding is currently under way (UKCRIND13392).

REFERENCES

- 1.D’Amico G, De Franchis R Cooperative study group. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003;38:599–612. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bañares R, Albillos A, Rincón D, Alonso S, González M, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, et al. Endoscopic treatment versus endoscopic plus pharmacologic treatment for acute variceal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:609–15. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien J, Triantos C, Burroughs AK. Management of varices in patients with cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.51. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: A meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch J, Berzigotti A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG. The management of portal hypertension: Rational basis, available treatments and future options. J Hepatol. 2008;48:S68–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ American association for the study of liver diseases. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386–400. doi: 10.1002/hep.20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick PA, Dick R, Panagou EB, Chin JK, Greenslade L, McIntyre N, et al. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic stent shunting as salvage treatment for uncontrolled variceal bleeding. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1324–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubmann R, Bodlaj G, Czompo M, Benkö L, Pichler P, Al-Kathib S, et al. The use of self-expanding metal stents to treat acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2006;38:896–901. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W, Hubmann R. Results of a new method to stop acute bleeding from esophageal varices: Implantation of a self-expanding stent. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2149–52. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zakaria MS, Hamza IM, Mohey MA, Hubmann RG. The first Egyptian experience using new self-expandable metal stents in acute esophageal variceal bleeding: Pilot study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:177–81. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.114516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holster IL, Kuipers EJ, van Buuren HR, Spaander MC, Tjwa ET. Self-expandable metal stents as definitive treatment for esophageal variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2013;45:485–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright G, Lewis H, Hogan B, Burroughs A, Patch D, O’Beirne J. A self-expanding metal stent for complicated variceal hemorrhage: Experience at a single center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dechêne A, El Fouly AH, Bechmann LP, Jochum C, Saner FH, Gerken G, et al. Acute management of refractory variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis by self-expanding metal stents. Digestion. 2012;85:185–91. doi: 10.1159/000335081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]