Abstract

Background:

Vivax malaria is the most widely distributed human malaria and is responsible for up to 400 million infections every year. Recently, it has become evident that Plasmodium vivax monoinfection could also result in multiple organ dysfunction and severe life-threatening disease as seen in Plasmodium falciparum infection.

Materials and Methods:

The aim of this study was to note the different clinical and biochemical profiles of adult patients with the severe vivax malaria with regards to complications and outcome. This was a prospective observational study carried out at a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata over 9 month's period. Detailed history and examination findings were noted in all patients. Their clinical presentations, complications, course in ward until discharge or death was noted.

Results:

A total of 900 cases of vivax malaria were included in the study. Severe disease was present in 200 (22.2%) cases of malaria. There were 108 (54%) patients with single complication (SC) and 92 (46%) patients with the multiple complications (MC). Patients with SC had jaundice (48.1%) followed by cerebral involvement (25.9%), renal failure (7.4%), and pulmonary involvement (3.7%). The MC was found in various combinations and the majority (47.8%) had constellation of two different complications. The mortality rate of patients with the SC and MC was 7.4% and 34.8%. The overall mortality observed in severe vivax malaria was 20% (40/200).

Conclusions:

In recent years, the clinical pattern of vivax malaria has changed. Severe vivax malaria is now very common with increasing mortality. Not only the number, but also the type of complication influences the outcome of complicated malaria.

KEY WORDS: Complications, mortality, outcome, Plasmodium vivax, severe malaria

INTRODUCTION

Plasmodium vivax infection has been considered for a long time a benign and self-limited disease. Nevertheless, P. vivax is responsible for 70-390 million infections each year, and outside of the African continents vivax malaria accounts for more than 50% of all malaria cases, yet the morbidity associated with this infection and its spectrum of disease is less studied.[1] Historically, cases of complicated P. vivax malaria have been rare and documented almost exclusively by case reports or small case series. Recent evidence from larger studies performed in Melanesian populations has however, reinforced the association between vivax malaria, severe complications, and death.[2,3,4] Increasing resistance to chloroquine and commonly used antimalarials in P. vivax parasites and the recent reports of involvement of this species in complicated malaria suggests the need for further research in vivax malaria. Taking this background, we planned a study in a tertiary care center in Kolkata from June 2011 to March 2012 to note the clinical and laboratory profile of patients admitted with severe vivax malaria along with its complications and outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective study was planned from June 2011 to March 2012 in a tertiary care center in Kolkata. Patients willing to give consent, older than 12 years of age and of either sex, with the peripheral smear positive for P. vivax were included in the study. All P. vivax cases enrolled in the study underwent OptiMAL malarial antigen test to rule out falciparum-vivax co-infection (mixed malaria). Other important causes of febrile illness were excluded as appropriate. During the study period, a total of 900 cases of vivax malaria were encountered out of which 200 showed features of severe malaria. Severe malaria was diagnosed as per the guidelines of World Health Organization (WHO).[5] Detailed history and the clinical examination was noted. Routine hematological and biochemical investigations were carried out as per treating physician's decision. Severe vivax malaria was treated with artemisinin based combination therapy as per hospital policy along with other supportive measures. Patients were followed-up until discharge or death. Complications such as anemia, hypoglycemia, convulsion, renal failure, jaundice, and circulatory collapse were treated appropriately. The patients who recovered and those who expired were grouped. They were also grouped under single and multiple complications (MC).

The study was approved by hospital ethics committee and the information obtained from this study were tabulated in a master chart and then analyzed to obtain measurable data. Percentages were calculated for a number of patients in different groups to convey appropriate statistical information.

RESULTS

Out of 900 admissions of vivax malaria, 200 patients of severe malaria according to WHO 2000 definition were recruited in the study. The fever before admission was continuous in 54% of the cases, intermittent in 38% cases, and remittent in the remaining 8%. Most of the patients (78%) had presented with acute illness of 2-7 days duration of fever, 18% the fever was of 8-14 days duration and 4% it was >14 days. A large number of patients (132) presented with history of jaundice (66%). Fifty six percent of the patients presented with impaired consciousness. In 22%, the presenting feature was delirium and 34% presented with unconsciousness. Generalized convulsions were seen in 28 (14%) patients as the presenting symptom associated with altered sensorium. History of dark colored urine with oliguria was noted in 30% of cases. Diarrhea (6-8 times/day) with diffuse abdominal pain was the presenting symptom in 4% of the patients, although, bleeding tendency was seen in 4 cases who had purpura. Sixty six percent of the patients had clinically recognizable icterus. Hepatomegaly was found in 64% of the patients. Splenomegaly was found in 84% of the patients. Four patients had purpuric eruptions.

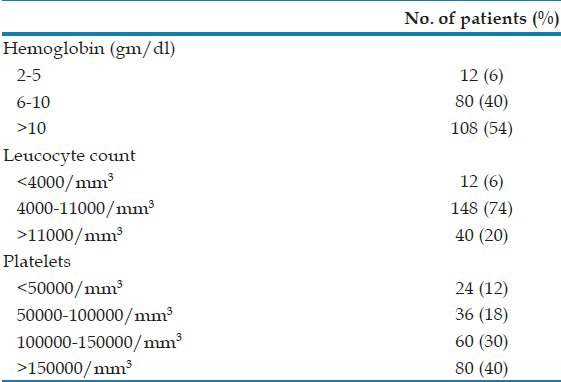

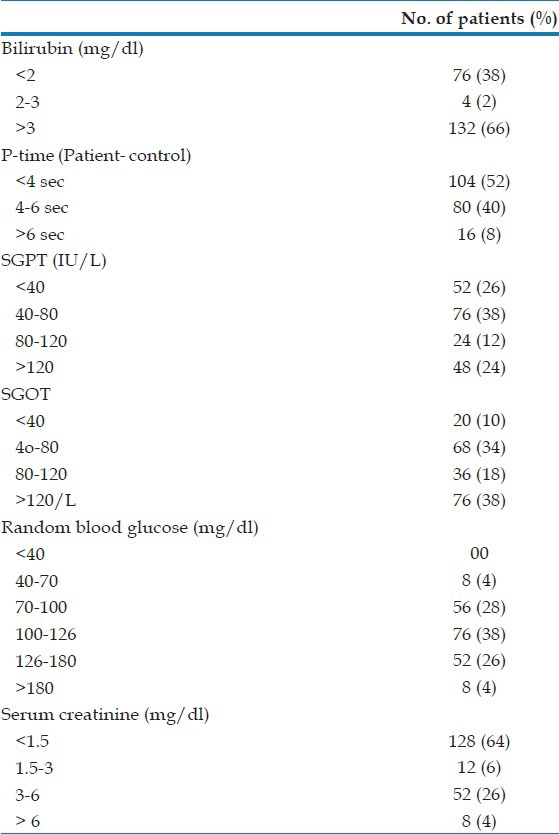

Moderate to severe anemia was seen in 46% of severe vivax malaria patients among whom 20% required blood transfusion. 20% had leukocytosis and 6% had leucopenia on admission. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/cmm) was found in 60 patients (30%) among whom severe thrombocytopenia was noted in 12% [Table 1]. However, bleeding manifestations occurred in only four patients. A total of 132 patients (66%) had serum total bilirubin level of >3 mg/dl, the highest being 31.2 mg/dl. Serum alaline aminotransaminase (ALT) level was increased >3 fold (120 IU/l) in 48 patients (24%), whereas 76 patients (38%) had aspartate aminotransaminase (AST) level more than 3 times the upper normal limit. A raised serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dl) was seen in 72 patients (36%) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Hematological parameters of the patients

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters of the patients

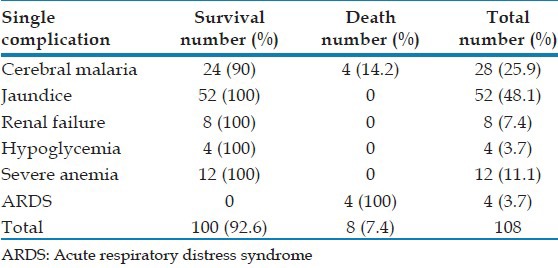

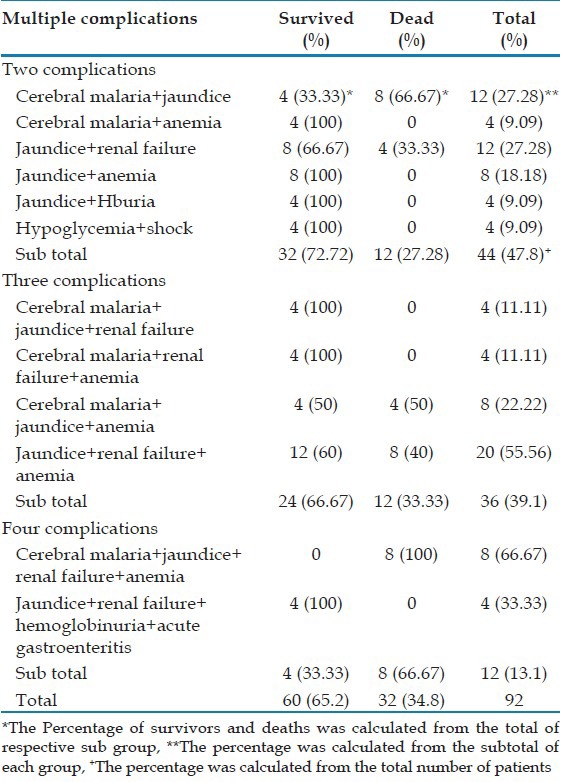

There were 108 (54%) patients with the single complication (SC) and 92 (46%) patients with MC. Patients with SC had jaundice (48.1%) followed by cerebral malaria (25.9%), severe anemia (11.11%), renal failure (7.4%), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (3.7%) [Table 3]. The MC were found in various combinations and majority (n = 44, 47.8%) had constellation of two different complications. Renal failure with jaundice (12/44, 27%) was the most common combination. Regardless of the number of complications, jaundice was present in 86.9% (80 of 92) patients with MC. Cerebral malaria was present in 34% (68 of 200) patients alone or in combination, whereas jaundice alone or in combination was found in 66% of the patients (132 of 200). The mortality rate of patients with SC and MC was 7.4% and 34.8% (P < 0.05). The overall mortality was 20% [Table 4]. We analyzed the 40 cases of malaria deaths. Most of them were symptomatic for >6 days before coming to us. Details of treatment before hospitalization were not available in the majority of cases.

Table 3.

Single complication in severe vivax malaria

Table 4.

Multiple complications in severe vivax malaria

There is significant linear correlation between mortality and number of complications. The mortality rose from 7.4% to 66.7% when compared patients with single and MC (up to 4). Among patients with SC, the mortality was 100% in patients with respiratory distress and 14.2% in cerebral malaria. However, there were no deaths in patients with jaundice, renal failure, anemia, and hypoglycemia. Among patients with MC, the mortality was high when the combination of jaundice and renal failure was present (20 of 40, 50%).

DISCUSSION

In the past few years, many cases of severe vivax malaria were seen and some cases resulted in death. The reported severe manifestations in vivax malaria include cerebral malaria,[6] hepatic dysfunction,[7,8] renal dysfunction,[9,10] severe anemia,[7,8] ARDS, and multiple organ involvement. Hence, this study was carried out to find out various complications of vivax malaria and their effects on outcome. The exact causes of changes in the clinical profile of vivax malaria are uncertain and may include genetic alterations of the parasite or change in vector and its biting habits or drug resistance.

Previously, it was thought that the severe disease with vivax infection is actually caused by co-infection of vivax and falciparum species. However, with application of the recently developed tests of malarial antigen it has become evident that vivax monoinfection can be a cause of severe malaria. In 2009 Kochar et al. reported a series of severe vivax malaria from Bikaner. They used antigen and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).test to exclude the falciparum co-infection.[11] The mechanisms of organ involvement in vivax malaria are controversial. Evidences[1,12,13] suggest that probable role of inflammatory and immunological response in the pathophysiology of severe vivax malaria.

In our study, complications seen in vivax malaria were cerebral malaria, hyperbilirubinemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia acute renal failure (ARF) and ARDS. The complications of vivax malaria observed by Sharma et al. in a study from Delhi[14] were thrombocytopenia, hepatic dysfunction, renal failure, ARDS, and hemolysis. Tjitra et al.[3] found anemia, ARDS, cerebral malaria as chief complications of vivax malaria in Papua, Indonesia. Severe anemia and respiratory distress were also noted as complications of vivax malaria by Genton et al.[4] The incidence of severe disease among inpatients of vivax malaria in our study (22.2%) was a bit higher as compared to that found by other studies, probably biased by the fact the hospital is a tertiary care center.

Out of the 200 patients, 60% had jaundice alone or in combination with other complications. Jaundice may be a combination of prehepatic (due to hemolysis), hepatic and cholestatic components. Hepatic dysfunction due to microvascular sequestration of parasitized red cells causes significant rises in serum bilirubin concentration, mild elevations of AST and ALT and prolongation of prothrombin time.[15] Close to half of patients with cerebral malaria had jaundice in this study. Although consciousness was impaired in almost 56% of cases in this study, only 34% had cerebral malaria as per WHO definition. History of convulsion was present in 14% of the patients. Seizures are attributed to various factors such as hyperpyrexia, lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia etc., Limaye et al. found 12 cases of cerebral involvement due to vivax malaria in their study.[16]

Moderate to severe anemia was noted in 46% patients, 20% needed a blood transfusion. Severe anemia occurs in vivax malaria due to recurrent bouts of hemolysis of predominantly uninfected erythrocytes with increased fragility.[12] The incidence of anemia was 86.4% in Bikaner study and 54% in another study.[11] Recurrent infections due to treatment failure and relapse from the liver stages result in up to 80% of patients having recurrent malaria within 4 weeks[17,18] and provide a plausible explanation for our observations that almost 6% of patients hospitalized with P. vivax have severe anemia.

Sixty percent of the patients were found to have thrombocytopenia. In 12%, the thrombocytopenia was severe. Bleeding due to thrombocytopenia was seen in the form of epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, and hematuria. The platelet count increased with the treatment of malaria. Immune mediated lysis is the major mechanism of thrombocytopenia in malaria.[19] Thrombocytopenia was more common in severe vivax malaria as compared to falciparum malaria in a recent hospital-based study by Nadkar et al.[20] Studies have demonstrated that acquired storage pool deficiency of platelet could be induced by circulating platelet antibodies. Damaged platelets may release adenosine diphosphate from their granules and then circulate as exhausted platelets.[19] Thrombocytopenia is also caused by increased splenic platelet clearance.

Awareness of the unrecognized presentations of complicated vivax malaria such as hepatic dysfunction jaundice and renal failure is needed among primary care physicians. Routinely, jaundiced patients with altered consciousness and a short history are considered to have viral hepatitis rather than malarial hepatitis. This can be a fatal error in terms of prompt institution of appropriate therapy. There was a significant association of ARF with rising bilirubin levels. This elevation of bilirubin was typically an increase in conjugated bilirubin. The concomitant renal failure may contribute to the elevated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia by virtue of decreased excretion of conjugated bilirubin. Hepatic dysfunction was the most common complication seen in severe vivax malaria in the study in Bikaner followed by renal failure.[16]

We have found only four patients with ARDS. Nadkar et al. study had 8 patients with vivax malaria with ARDS, out of which 5 succumbed to death.[20] In African children with Plasmodium falciparum, respiratory distress is associated with metabolic acidosis and/or concurrent pneumonia.[21,22] However, the etiology of P. vivax-associated respiratory distress in Asia is unknown and will require detailed clinical studies to determine the relative contributions of acute lung injury, possible pulmonary parasite sequestration, acidosis, and co-infections.[23]

Mortality increased with an increasing number of complications. The mortality was 7.4% among patients with SC and 34.8% among patients with MC. ARDS was the most serious complication associated with mortality. Anemia, jaundice, and hypoglycemia were less severe forms of complications. The combination of cerebral malaria, jaundice, renal failure and anemia was more fatal. Hence, not only the number of but also the type of complication influenced the outcome of complicated malaria, which is similar to sepsis with the multiple organ dysfunction.

Forty patients died and the cause of death may be secondary to multi organ dysfunction secondary to different cytokines and other tissue factors. Once the complications develop removal of parasites could not reverse the organ damage and hence the mortality. Therefore, in addition to antimalarial drugs, organ support is mandatory in the management of severe malaria.

The results of this study are notable for various reasons. We demonstrated that the increasing number of patients has been afflicted with MC. Although P. vivax malaria is widely considered benign, recent studies have demonstrated that it accounts for a substantial proportion of hospitalized malaria patients in agreement with our study.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients of vivax malaria should be monitored for occurrence of different complications as their early detection and the treatment or referral to higher center can be life-saving. The mortality in vivax malaria increases with increasing age. Thrombocytopenia is very common in severe vivax infection. Renal, hepatic, lung, and cerebral involvement are occurring with increasing frequency. In this hospital based study, the incidence of various complications may be higher than the incidence in the community; and is a limitation of the study. Severe vivax malaria is a relatively new clinical entity and further studies from different parts of India are needed to decipher the underlying pathogenesis of severe disease, and the degree to which it is related to the emergence of multidrug resistant strains of P. vivax.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Price RN, Tjitra E, Guerra CA, Yeung S, White NJ, Anstey NM. Vivax malaria: Neglected and not benign. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:79–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcus MJ, Basri H, Picarima H, Manyakori C, Sekartuti, Elyazar I, et al. Demographic risk factors for severe and fatal vivax and falciparum malaria among hospital admissions in northeastern Indonesian Papua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:984–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Sugiarto P, Warikar N, Kenangalem E, Karyana M, et al. Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium Vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: A prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genton B, D’Acremont V, Rare L, Baea K, Reeder JC, Alpers MP, et al. Plasmodium Vivax and mixed infections are associated with severe malaria in children: A prospective cohort study from Papua New Guinea. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:S1–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beg MA, Khan R, Baig SM, Gulzar Z, Hussain R, Smego RA., Jr Cerebral involvement in benign tertian malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:230–2. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohapatra MK, Padhiary KN, Mishra DP, Sethy G. Atypical manifestations of Plasmodium Vivax malaria. Indian J Malariol. 2002;39:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochar DK, Saxena V, Singh N, Kochar SK, Kumar SV, Das A. Plasmodium Vivax malaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:132–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta KS, Halankar AR, Makwana PD, Torane PP, Satija PS, Shah VB. Severe acute renal failure in malaria. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prakash J, Singh AK, Kumar NS, Saxena RK. Acute renal failure in Plasmodium Vivax malaria. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:265–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochar DK, Das A, Kochar SK, Saxena V, Sirohi P, Garg S, et al. Severe Plasmodium Vivax malaria: A report on serial cases from Bikaner in northwestern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:194–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anstey NM, Russell B, Yeo TW, Price RN. The pathophysiology of Vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrade BB, Reis-Filho A, Souza-Neto SM, Clarêncio J, Camargo LM, Barral A, et al. Severe Plasmodium Vivax malaria exhibits marked inflammatory imbalance. Malar J. 2010;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A, Khanduri U. How benign is benign tertian malaria? J Vector Borne Dis. 2009;46:141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tangpukdee N, Thanachartwet V, Krudsood S, Luplertlop N, Pornpininworakij K, Chalermrut K, et al. Minor liver profile dysfunctions in Plasmodium vivax, P. malaria and P. ovale patients and normalization after treatment. Korean J Parasitol. 2006;44:295–302. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2006.44.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limaye CS, Londhey VA, Nabar ST. The study of complications of vivax malaria in comparison with falciparum malaria in mumbai. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Brockman A, Edstein MD, et al. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:351–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baird JK, Hoffman SL. Primaquine therapy for malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1336–45. doi: 10.1086/424663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Looareesuwan S, Davis JG, Allen DL, Lee SH, Bunnag D, White NJ. Thrombocytopenia in malaria. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadkar MY, Huchche AM, Singh R, Pazare AR. Clinical profile of severe Plasmodium vivax malaria in a tertiary care centre in Mumbai from June 2010-January 2011. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bejon P, Berkley JA, Mwangi T, Ogada E, Mwangi I, Maitland K, et al. Defining childhood severe falciparum malaria for intervention studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, Mwangi I, Winstanley M, Marsh V, et al. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1399–404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anstey NM, Handojo T, Pain MC, Kenangalem E, Tjitra E, Price RN, et al. Lung injury in vivax malaria: Pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:589–96. doi: 10.1086/510756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]