Abstract

Fructans are the major component of temporary carbon reserve in the stem of temperate cereals, which is used for grain filling. Three families of fructosyltransferases are directly involved in fructan synthesis in the vacuole of Triticum aestivum. The regulatory network of the fructan synthetic pathway is largely unknown. Recently, a sucrose-upregulated wheat MYB transcription factor (TaMYB13-1) was shown to be capable of activating the promoter activities of sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase (1-SST) and sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase (6-SFT) in transient transactivation assays. This work investigated TaMYB13-1 target genes and their influence on fructan synthesis in transgenic wheat. TaMYB13-1 overexpression resulted in upregulation of all three families of fructosyltransferases including fructan:fructan 1-fructosyltransferase (1-FFT). A γ-vacuolar processing enzyme (γ-VPE1), potentially involved in processing the maturation of fructosyltransferases in the vacuole, was also upregulated by TaMYB13-1 overexpression. Multiple TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs were identified in the Ta1-FFT1 and Taγ-VPE1 promoters and were bound strongly by TaMYB13-1. The expression profiles of these target genes and TaMYB13-1 were highly correlated in recombinant inbred lines and during stem development as well as the transgenic and non-transgenic wheat dataset, further supporting a direct regulation of these genes by TaMYB13-1. TaMYB13-1 overexpression in wheat led to enhanced fructan accumulation in the leaves and stems and also increased spike weight and grain weight per spike in transgenic plants under water-limited conditions. These data suggest that TaMYB13-1 plays an important role in coordinated upregulation of genes necessary for fructan synthesis and can be used as a molecular tool to improve the high fructan trait.

Key words: Fructans, fructosyltransferases, gene regulation, MYB transcription factor, γ-vacuolar processing enzyme, wheat.

Introduction

Fructans are oligo- and polysaccharides that are produced by many plant species, including temperate monocots and dicots, as well as by some bacteria and fungi (Pollock, 1986). In angiosperms, fructans can be found in about 15% of all species (Hendry, 1987), including many temperate cereals like wheat and barley. Fructans are mainly synthesized and stored in plant vacuoles by a group of fructosyltransferases belonging to plant glycoside hydrolase family 32 enzymes (Pollock, 1986; Darwen and John, 1989; Vijn et al., 1997; Ritsema and Smeekens, 2003a; Chalmers et al., 2005; Altenbach et al., 2009; Van den Ende et al., 2009). Plant fructosyltransferases have been extensively researched, including characterization of the 3D structure of Pachysandra terminalis fructosyltransferase (Lammens et al., 2012). In wheat and barley, three enzyme families that synthesize graminan-type fructans consisting of β-2,6 linked fructosyl units with β-2,1 branches are sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase (1-SST), sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase (6-SFT), and fructan:fructan 1-fructosyltransferase (1-FFT) (Lüscher et al., 1996; Müller et al., 2000; Kawakami and Yoshida, 2002, 2005; Ritsema and Smeekens, 2003b).

Fructans are accumulated when the production of photoassimilates exceeds the need (Pollock, 1984). In wheat, stems are the major storage sites of fructans (Ruuska et al., 2008). Fructans are the major component of water-soluble carbohydrates (WSCs) in the fructan accumulation phase in wheat stems (Ruuska et al., 2006). WSCs in the stem in the peak accumulation phase, which are mainly fructans, can account for over 40% of the stem dry weight (Blacklow et al., 1984) and are important carbon reserve for grain filling in temperate cereals. The contribution of stored WSCs to grain filling ranges from 20 to 45%, depending on the incorporation of respiration and other carbon sinks (Austin et al., 1977; Bonnett and Incoll, 1992, 1993; van Herwaarden et al., 1998a; Wardlaw and Willenbrink, 2000). WSCs in stems become even more important under drought stress conditions where the contribution of stem reserves to grain yield increases significantly (Aggarwal and Sinha, 1984; van Herwaarden et al., 1998b). Positive association of stem WSC concentration with grain weight or yield in wheat has been observed in many studies, particularly under water-limited environments (Foulkes et al., 2002; Asseng and van Herwaarden, 2003; Xue et al., 2008b, 2009; McIntyre et al., 2011, 2012). This positive association is mainly attributed to the fructan component of the stem WSCs.

Besides being important for temporary carbon storage, fructans have also been reported to protect cells from drought and cold stress. Pilon-Smits et al. (1995) have shown improvement of drought tolerance of transgenic tobacco plants that express a bacterial fructosyltransferase, and Kawakami et al. (2008) have found the increased cold tolerance of rice plants expressing 1-SST or 6-SFT from wheat. This increased tolerance is likely due to their stabilizing effect on the membranes of the stressed cells and serving as an antioxidant (Demel et al., 1998; Hincha et al., 2000; Kawakami et al., 2008; Valluru and Van den Ende, 2008, 2009; Livingston et al., 2009; Bolouri-Moghaddam et al., 2010).

The coding sequences of many fructosyltransferases have been isolated from various plant species. Sprenger et al. (1995) reported the isolation of the 6-SFT cDNA from barley, followed by the publication of many other fructosyltransferases from different species (de Halleux and Cutsem, 1997; Hellwege et al., 1997; Vijn et al., 1997, 1998; Van der Meer et al., 1998; Van den Ende et al., 2000, 2006; Kawakami and Yoshida, 2002, 2005; Lasseur et al., 2006, 2011). Enzyme activities and the expression of the genes encoding these enzymes have been shown to be regulated by various signals. For example, sucrose, besides being a substrate for the fructan synthesis, has been suggested as a signalling molecule that is able to upregulate the expression of genes in the fructan synthetic pathway (Wagner et al., 1986; Müller et al., 2000; Koroleva et al., 2001; Martínez-Noël et al., 2001, 2009, 2010; Nagaraj et al., 2001, 2004; Lu et al., 2002; Ruuska et al., 2008, Ritsema et al., 2009; Xue et al., 2011a, 2013). Other factors that play an important role in the fructan synthetic pathway are protein kinases and phosphatases (Martínez-Noël et al., 2001, 2009, 2010; Kusch et al., 2009; Ritsema et al., 2009).

Despite many studies on fructans and genes involved in fructan synthesis and regulation, regulatory pathways involving transcription factors, protein kinases, and phosphatases are largely unknown. Recently, one transcription factor has been identified to be potentially involved in the regulation of Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT genes. Xue et al. (2011a) have shown three highly homologous R2R3 MYB transcription factor genes (TaMYB13-1, TaMYB13-2, and TaMYB13-3) that are closely co-regulated with Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT genes in wheat, and TaMYB13-1 is a predominantly expressed gene among these three. The expression of TaMYB13-1 is upregulated by sucrose and during stem development. The activation of the expression of Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT promoter-driven reporter genes by TaMYB13-1 has been demonstrated in transient transactivation assays.

To gain further insight into the role of TaMYB13-1 in the fructan synthetic pathway in wheat, this work characterized transgenic wheat overexpressing TaMYB13-1. Expression analysis of TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines using Affymetrix wheat genome array and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR revealed that TaMYB13-1 upregulated the expression of not only Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT but also Ta1-FFT family genes and other genes associated with fructan accumulation (e.g. fructokinase 1 (FK1) and γ-vacuolar processing enzyme 1 (γ-VPE1)). TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs were also found in the promoter regions of the Ta1-FFT1 and Taγ-VPE1 genes and verified with in vitro DNA-binding assays. These two new target genes identified in this study showed positive correlation with TaMYB13-1 expression in all datasets analysed. The transgenic plants had higher fructan and WSC levels as well as higher spike weight and grain weight per spike in comparison with wild-type control plants, demonstrating that a TaMYB13-1-mediated regulon plays an important role in modulating fructan accumulation and conferring the high fructan trait.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Spring wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Bobwhite SH 98 26) was grown in a controlled environment room in 1.5-l pots containing a mixture of sand:soil:peat (3/1/1). The room had the following day/night settings: 16/8 light/dark (500 μmol m–2 s–1), 20/16 °C and 60/80% relative humidity (Kam et al., 2008). Two organs selected for gene expression and WSC analyses are flag leaf (an important organ of photosynthesis for contributing to wheat grain yield) and stem (a major organ for fructan storage). As the top internode (peduncle) of the stem contains a much more abundant amount of RNA than the lower internodes, only top internode samples were used for main analyses in this study. To minimize diurnal fluctuations of gene expression samples were harvested 6–7h after the lights turned on. Harvested samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at –80 °C.

For evaluation of yield-related phenotypes under mild drought conditions, plants were grown in 14.3-l pots with a 29-cm top diameter. Each pot grew six plants, which mimics plants grown in a small plot. The plants were watered only when they showed mild water-deficit stress.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Samples were ground in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle. RNA was isolated using Plant RNA Reagent from Invitrogen according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was removed as described by Xue and Loveridge (2004) and the isolated RNA was purified using the RNeasy Plant mini-kit column (Qiagen), following the directions of the kit. For quantitative reverse-transcription PCR, 5 μg total RNA was retro-transcribed using Superscript III first strand synthesis kit from Invitrogen, according the manufacturer’s instruction.

Real-time PCR

Relative transcript levels of genes were determined from cDNA with an ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system using SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplification efficiencies of gene-specific primers were determined by serial cDNA dilutions. Relative gene expression levels were calculated as described by Shaw et al. (2009), where the relative mRNA value of each gene in a given sample is estimated using the mean of two normalized values against that of two internal control genes, TaRPII36, RNA-polymerase II 36 kD subunit (Xue et al., 2006) and TaRP15, RNA polymerases I, II, and III 15 kD subunit (Xue et al., 2008b). Primers used for the amplification of Ta1-SST1, Ta1-SST2, Ta6-SFT1, Ta6-SFT2, Ta1-FFT1, Ta1-FFT2, TaRP15, and TaRPII36 were as published by Xue et al. (2008a, b, 2011a). The following real-time PCR primer pairs were used for the quantification of Taγ-VPE1 and TaFK1 mRNA levels: 5′-CGAGCTGATTGGAAACCTTCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCGAGCCACATTGTGATTCAA-3′ (reverse) for Taγ-VPE1; 5′-TCTTGGAGATCAAGGATGCAAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACCAGCACCTGTCGTATCAAC-3′ (reverse) for TaFK1.

Transformation of wheat with TaMYB13-1 construct

TaMYB13-1 expression construct (Hv6-SFT:TaMYB13-1:rice rbcS 3′) was made by inserting the coding region of TaMYB13-1 after the barley Hv6-SFT promoter (Nagaraj et al., 2001), using expression construct plasmids in the cloning vector pSP72 as described by Xiao and Xue (2001) and Xue et al. (2003), followed by nucleotide sequencing. The selectable marker cassette containing rice act1:bar:nos 3′ was used to co-transform Bobwhite wheat plants. Both cassettes were PCR amplified and used for transformation of immature Bobwhite SH 98 26 embryos using the particle bombardment as described by Pellegrineschi et al. (2002). Transgenic plants were selected with the herbicide phosphinothricin and grown in a controlled environmental growth room as described above. The presence of the Hv6-SFT:TaMYB13-1:rice rbcS 3′ cassette was verified by real-time PCR using genomic DNA as described previously (Xue et al., 2011b).

WSC extraction and analysis

The flag leaf and top internode samples were harvested from plants at anthesis grown in controlled environment as described above. The WSC levels were measured using the modified anthrone procedure (Xue et al., 2009). The levels of sugars (sucrose, glucose, and fructose) were determined using HPLC (Waters, Massachusetts, USA) and separated on an analytical column (CarboPac PA-100; Dionex, California, USA) using 50–150mM NaOH as a mobile phase. The fructan fraction of the WSC extracts was analysed by HPLC measurement of the glucose and fructose levels of the WSC extracts before and after mild acid hydrolysis of fructans. The mild acid hydrolysis of fructans was performed according to the method of Van den Ende et al. (2003). For TLC analysis, approximately 80 μg WSCs per lane were loaded on 20cm × 20cm silica-gel-coated plates (0.2mm thick, TLC Silica gel 60 F254, Merck). The TLC was run as described by Incoll et al. (1989) with 1-propanol:ethyl-ethanoate:water (5/3/2, v/v/v). Sugars and fructans separated on TLC plates were visualized by spraying the plates with urea-phosphoric acid and heating at 110 °C (Wise et al., 1955). WSCs extracted from Helianthus tuberosus were used as markers for fructans.

Expression analysis using Affymetrix Wheat GeneChip Array

RNA from the flag leaves of plants at anthesis grown in controlled environment was extracted and processed as described above. RNA quality check, cRNA preparation, labelling, hybridization, and data acquisition of Affymetrix Wheat GeneChips were performed by the microarray service at the Australian Genome Research Facility (Melbourne, Australia). The Affymetrix GeneChip data were normalized using GeneChip robust multiarray average, developed by Wu et al. (2004), using the Affymetrix package within Bioconductor, running within the R statistical programming environment (www.r-project.org). The dataset (the accession number GSE42000) was deposited at the NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Probesets with expression levels below 100 in both the control and transgenic groups were discarded, so were probesets that had a differential expression value with a P-value >0.05.

Determination of the genomic DNA sequences of TaMYB13-1 target genes

The sequences of the Affymetrix probes for the target genes were used as query sequences to blast the genomic sequence of wheat from CerealsDB (Wilkinson et al., 2012). The retrieved sequence was subsequently used in a new blast search to retrieve additional sequences. The final retrieved genomic sequence contigs were cross checked with EST data from NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and the DFCI Triticum aestivum Gene Index (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/tgi/gimain.pl?gudb=wheat). The blast search was continued until at least 1000bp upstream of the ATG was obtained if it was possible.

In vitro DNA-binding assays

In vitro DNA-binding assays using cellulase D (CELD) as a reporter were performed as described by Xue (2002), using streptavidin-coated 96-well plate and binding/washing buffer (25mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.0, 50mM KCl, 0.2mM EDTA, and 0.5mM DTT) containing 0.15 μg μl–1 shared herring sperm DNA, 0.3mg ml–1 bovine serum albumin, 10% glycerol, and 0.025% Nonidet P-40. For each assay, 40 000 fluorescent units h–1 of the CELD activity of TaMYB13-1-CELD protein and 2 pmol of biotinylated probes were used. The cellulase activity of TaMYB13-1-CELD proteins bound to immobilized biotinylated probes was assayed by incubation in 100 μl of the CELD substrate solution (1mM methylumbelliferyl β-d-cellobioside in 50mM Na-citrate buffer, pH 6.0) at 40 °C for 3h. A biotin-labelled double-stranded oligonucleotide without a TaMYB13-1-binding site was used as a control of background activity. For the synthesis of the biotin-labelled probes, oligonucleotides were designed around the predicted TaMYB13-1 DNA-binding sites present in the genomic sequence as described above, including 10bp upstream and downstream these sites. The oligonucleotides were manufactured by Geneworks (Adelaide, Australia). The biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides were synthesized as described by Xue (2005).

Results

Overexpression of TaMYB13-1

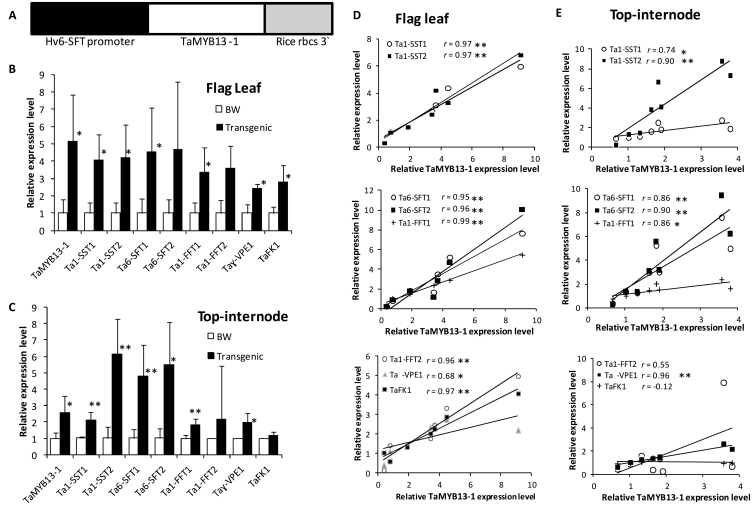

To gain a better insight into the target genes of TaMYB13-1, this work expressed the coding sequence of the TaMYB13-1 cDNA derived from correctly spliced mRNA under the control of the 6-SFT promoter from barley (Hv6-SFT) and rice rbcS 3′ region (Fig. 1A) in wheat, as Hv6-SFT is a well-studied fructosyltransferase gene and is expected to be expressed in organs where fructan accumulation normally occurs. The presence of TaMYB13-1 in T0 transgenic wheat plants was verified by genomic quantitative PCR (data not shown), using primers that amplify the 3′-untranslated region of rice rbcS (Xue et al., 2011b). In the T1 generation, expression of TaMYB13-1 transgene was confirmed in the mature leaves of transgenic plants using quantitative reverse-transcription PCR and rice rbcS 3′ region primers (data not shown). The T2 plants of five independent TaMYB13-1 transgene expressing lines (a20, a21, b2, b13, and b36) were analysed for the expression level of TaMYB13-1 in the flag leaves at anthesis. The primers used amplified both the correctly spliced endogenous TaMYB13-1 as well as the transgene TaMYB13-1. The expression levels of TaMYB13-1 in the flag leaves of transgenic plants at anthesis ranged from 3- (a21) to 9-times (b36) higher than that of wild-type control plants (Bobwhite). Subsequently, the flag leaf and top internode samples of plants in the fructan accumulation phase (at anthesis) were selected for comparative analysis of expression levels. The average increases in the expression levels of TaMYB13-1 in the flag leaf and top internode (peduncle) of transgenic plants at anthesis, in comparison with wild-type control plants, are shown in Fig. 1B and C.

Fig. 1.

Expression levels of TaMYB13-1 and its target genes in TaMYB13-1 transgenic lines and Bobwhite (BW) control plants. (A) TaMYB13-1 expression cassette. (B, C) Relative expression levels of TaMYB13-1 and its target genes in the flag leaf (B) and top internode (peduncle) (C) of the plants at anthesis; values are means ± SD of 4–5 independent T2 transgenic lines or three biological replicates of Bobwhite; the mean expression value of each gene in the Bobwhite control group was set at 1. (D, E) Expression correlation between TaMYB13-1 and its putative target genes in the flag leaf (D) and top internode (E); the expression level in each sample is relative to the mean expression value in the Bobwhite control group, which was set at 1. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Upregulation of TaMYB13-1 target genes in transgenic wheat

Transgenic lines were analysed to examine changes in the expression levels of TaMYB13-1 target genes. Since the expression levels of many genes might be affected by the upregulation of a transcription factor, this work used the Affymetrix Wheat GeneChip to study the expression of the wheat transcriptome, comparing the three transgenic lines (a20, b2, and b36) containing the highest TaMYB13-1 expression with three wild-type control plants. The flag leaf samples were used for Affymetrix array analysis because it was thought that overexpression of TaMYB13-1 might also affect the expression levels of genes related to the sucrose synthetic pathway in the leaf. From the generated dataset, genes were selected with expression levels notably increased or decreased (factor 2; P < 0.05). Thirty-two probesets (27 genes) had an increased expression level in the transgenic lines compared to the control plants (Table 1), whereas 18 probesets (18 genes) had a lower expression level (Supplementary Table S1, available at JXB online). This study decided to focus on the upregulated genes, since this would more likely result in the identification of direct targets of TaMYB13-1.

Table 1.

Genes increased in expression levels by at least 2-fold in TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic lines compared to Bobwhite control plants in Affymetrix wheat genome array data

Values are expression ratio (EXPR) of the mean of three independent transgenic lines to the mean of three biological replicates of Bobwhite.

| Probeset | Description | EXPR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ta.24195.1.A1_at | Unknown protein | 17.17 | 0.02 |

| TaAffx.71942.1.A1_at | Putative retro-element | 5.42 | 0.00 |

| Ta.3475.2.S1_at | Ta1-FFT2 and Ta1-FFT1 | 5.32 | 0.04 |

| Ta.3475.1.A1_at | Ta1-FFT2 | 4.35 | 0.02 |

| TaAffx.83540.1.S1_at | Unknown protein | 4.60 | 0.00 |

| Ta.2788.1.A1_at | Ta1-SST2 | 4.20 | 0.02 |

| Ta.2789.1.S1_a_at | Ta6-SFT2 | 3.92 | 0.03 |

| Ta.2789.2.S1_x_at | 3.31 | 0.03 | |

| Ta.2789.2.S1_at | 2.74 | 0.03 | |

| Ta.2789.1.S1_at | Ta6-SFT1 | 3.11 | 0.02 |

| Ta.12834.1.S1_s_at | TaMYB13-1, TaMYB13-2, and TaMYB13-3 | 3.73 | 0.05 |

| Ta.12258.1.A1_at | Unknown protein | 3.38 | 0.00 |

| Ta.7378.5.A1_at | Histone H2B | 3.10 | 0.04 |

| Ta.13965.1.S1_at | Ubiquitin-protein ligase | 2.88 | 0.04 |

| Ta.30798.3.S1_at | Vacuolar processing enzyme 3 (Taγ-VPE1) | 2.85 | 0.02 |

| Ta.15881.1.S1_at | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor | 2.61 | 0.02 |

| TaAffx.19583.2.A1_at | Microtubule-associated protein | 2.61 | 0.00 |

| TaAffx.59883.1.S1_at | Putative amino acid permease | 2.50 | 0.05 |

| Ta.10107.2.S1_a_at | Fructokinase (TaFK1) | 2.50 | 0.01 |

| Ta.10107.2.S1_x_at | 2.49 | 0.02 | |

| Ta.10107.1.S1_at | 2.18 | 0.02 | |

| Ta.25919.1.S1_at | MYB transcription factor | 2.45 | 0.04 |

| Ta.23069.1.S1_at | IAA31-auxin-responsive Aux/IAA family member | 2.42 | 0.05 |

| TaAffx.43914.1.S1_s_at | Unknown | 2.41 | 0.02 |

| Ta.1549.1.S1_at | Aspartyl protease family protein | 2.40 | 0.00 |

| Ta.20658.1.S1_a_at | Putative lipase | 2.36 | 0.01 |

| Ta.10838.1.S1_at | CCT motif family protein | 2.31 | 0.03 |

| Ta.10838.1.S1_x_at | 2.17 | 0.04 | |

| Ta.10772.1.A1_at | Nodulin-like protein | 2.26 | 0.03 |

| Ta.28063.1.S1_x_at | Glycine-rich protein | 2.21 | 0.01 |

| Ta.20658.2.S1_x_at | Esterase precursor | 2.16 | 0.03 |

| Ta.27746.1.S1_at | Unknown protein | 2.05 | 0.03 |

As expected, the hybridization signal of the Ta.12834.1.S1_s_at probeset, which can hybridize three highly homologous TaMYB13 genes (TaMYB13-1, TaMYB13-2, and TaMYB13-3) in both correctly and wrongly spliced forms (Xue et al., 2011a) as well as the Hv6-SFT promoter-driven TaMYB13-1 transgene, was higher in the transgenic lines than control plants (Table 1). Strikingly, the Ta.24195.1.A1_at probeset (an unknown-function gene) had a 17-fold increase in expression in the transgenic lines compared to the control plants. Among the upregulated genes with known function, the only pathway that is overrepresented was the one related to fructan synthesis. Of 32 upregulated probesets, 10 are related to the sucrose (Ta.10107.2.S1_a_at, Ta.10107.2.S1_x_at, and Ta.10107.1.S1_at) and fructan (Ta.3475.2.S1_at, Ta.3475.1.A1_at, Ta.27 88.1.A1_at, Ta.2789.1.S1_a_at, Ta.2789.2.S1_x_at, Ta.2789.2. S1_at, and Ta.2789.1.S1_at) synthetic pathways. Among these 10 probesets, five belong to Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT, which can be transactivated by TaMYB13-1, as shown in the previous study (Xue et al., 2011a).

Interestingly, Ta1-FFT1 and Ta1-FFT2, represented by the probeset Ta.3475.2.S1_at, had an increased hybridization signal in transgenic lines, which was >5-times higher than non-transformed Bobwhite control plants (Table 1). A similar increase in the signal of the Ta1-FFT2-specific probeset was observed. These data indicate that TaMYB13-1 has an impact on the expression of all three families of fructosyltransferases in wheat. Besides fructosyltransferases, other upregulated genes relevant to the fructan synthesis were a fructokinase gene (TaFK1) represented by three probesets and a γ-vacuolar processing enzyme gene (Taγ-VPE1).

To validate the upregulation of these genes, their expression levels were measured by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR in both the flag leaf and top internode. As shown in Fig. 1B, the upregulation of all genes was observed in the flag leaf, although the marked increases in the Ta6-SFT2 and Ta1-FFT2 mRNA levels were not statistically significant due to the large variation in expression among individual transgenic lines (a20, b2, b13, and b36). Therefore, this work tested the correlation in expression between TaMYB13-1 and its upregulated genes. The expression correlations between TaMYB13-1 and these tested genes in the flag leaf were all statistically significant (Fig. 1D). Similar results were obtained in the top internode, where the expression levels of all these tested genes were significantly increased in the five transgenic lines and were significantly correlated with the TaMYB13-1 mRNA level, except for Ta1-FFT2 and TaFK1 (Fig. 1C and E).

Because fructosyltransferase proteins are located in the vacuole and because plant mature fructosyltransferases generally consist of two subunits derived from proteolytic cleavage of their pre-proteins except the 1-FFT from Helianthus tuberosus (Koops and Jonker, 1994, 1996; Sprenger et al., 1995; Van den Ende et al., 1996, 2000), it was suspected that the TaMYB13-1-upregulated vacuolar processing Taγ-VPE1 might be a candidate for processing the maturation of fructosyltransferase proteins. Therefore, this work examined whether Taγ-VPE1 and fructosyltransferase genes were closely co-regulated in the expression datasets. Correlation analysis showed that the Taγ-VPE1 mRNA levels were highly correlated with these fructosyltransferase mRNA levels in the stem of recombinant inbred lines with contrasting fructan levels, during stem development and among samples of transgenic and control plants (Supplementary Fig. S1).

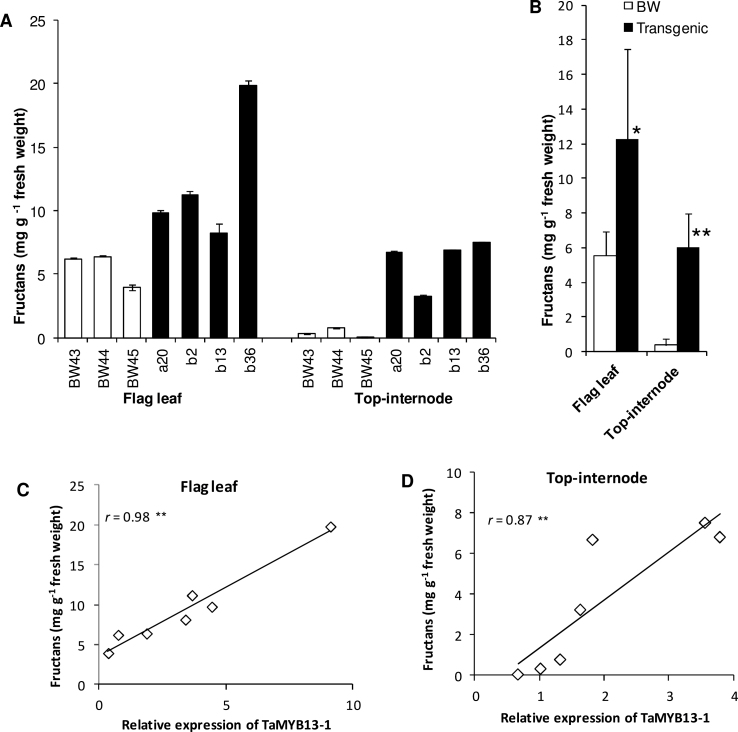

Enhanced fructan accumulation in TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic wheat

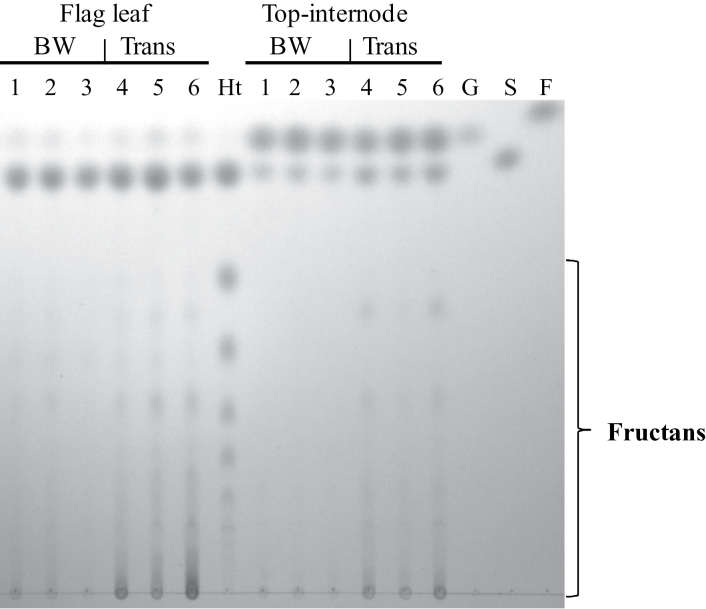

The expression data clearly points to the fructan synthesis pathway as a target for TaMYB13-1 regulation. It is known that a good correlation exists between Ta1-SST mRNA levels and its enzyme activity levels in wheat (Xue et al., 2008b), as well as Hv6-SFT mRNA levels and its enzyme activity levels in barley (Sprenger et al., 1995). Since genes from Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT families, together with Ta1-FFT family genes, were highly upregulated in the transgenic lines, the fructan and WSC concentrations in these transgenic lines were compared with wild-type control plants. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the fructan levels in the top internode as well as the flag leaf were higher in all of the four transgenic lines than in the control plants. The increase in fructan levels in the flag leaf and top internode of the transgenic group was statistically significant in comparison with the wild-type control group (Fig. 2B). There was also a slight increase in the sucrose level in the top internode of transgenic lines, but not in the leaf (see TLC analysis in Fig. 3). Correlation analysis showed highly significant positive relationships between TaMYB13-1 mRNA levels and fructan levels in the flag leaf and top internode in the dataset of these transgenic and control plants (Fig. 2C and D). Also, the WSC concentrations in the flag leaf and top internode were increased by 36 and 17%, respectively (P < 0.05; Table 2). The increase of WSC concentration in the flag leaf and top internode in the transgenic plants compared to control plants corresponds almost exclusively to the increased portion of fructan accumulation (about 6mg (g freshweight)–1, Fig. 2B). TLC analysis clearly illustrates an increase in the levels of fructans with various polymerization degrees in the transgenic lines compared to control plants (Fig. 3). The difference is especially clear in the top internode samples at anthesis, where the fructans in the control plants were barely visible, whereas the transgenic plants accumulated a significant amount of fructans.

Fig. 2.

Fructan concentrations in the flag leaf and top internode of transgenic plants overexpressing TaMYB13-1 and relationship between TaMYB13-1 mRNA levels and fructan levels. (A) Fructan concentration changes in individual transgenic lines in comparison with Bobwhite control plants (BW43/44/45); values are means ± SD of three replicates from the same plant. (B) Group comparison of fructan concentrations; values are means ± SD of four independent transgenic lines or three biological replicates of Bobwhite (BW). (C, D) Relationship between TaMYB13-1 mRNA levels and fructan levels in the flag leaf (C) and the top internode (D) in the datasets of the transgenic and Bobwhite control plants; the TaMYB13-1 expression level in each sample is relative to the mean expression value in the Bobwhite control group, which was set at 1. All samples were collected at anthesis. * P > 0.05; ** P > 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Thin-layer chromatogram of WSC extracts from the flag leaf and top internode of Bobwhite (BW) control plants and transgenic lines (Trans) overexpressing TaMYB13-1. Increase in fructan levels in transgenic lines is apparent both in the flag leaf and top internode. Lanes 1–3, BW43/44/45; lanes 4–6, TaMYB13-1 transgenic lines (a20, b2, and b36); lane Ht, WSC extract from Helianthus tuberosus. F, Fructose; G, glucose; S, sucrose.

Table 2.

Water-soluble carbohydrate concentrations in the flag leaf and top internode at anthesis from Bobwhite control plants and TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic plants

Values are means ± SD of three biological replicates of Bobwhite or five independent TaMYB13-1 transgenic lines (a20, a21, b2, b13, b36).

| WSC in flag leaf (mg (g freshweight)–1) | WSC in top internode (mg (g freshweight)–1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bobwhite | 18.20±2.59 | 32.03±2.80 |

| Transgenic | 24.73±5.15* | 37.58±2.90* |

| % increase | 35.9 | 17.3 |

WSC, water-soluble carbohydrate. * P < 0.05.

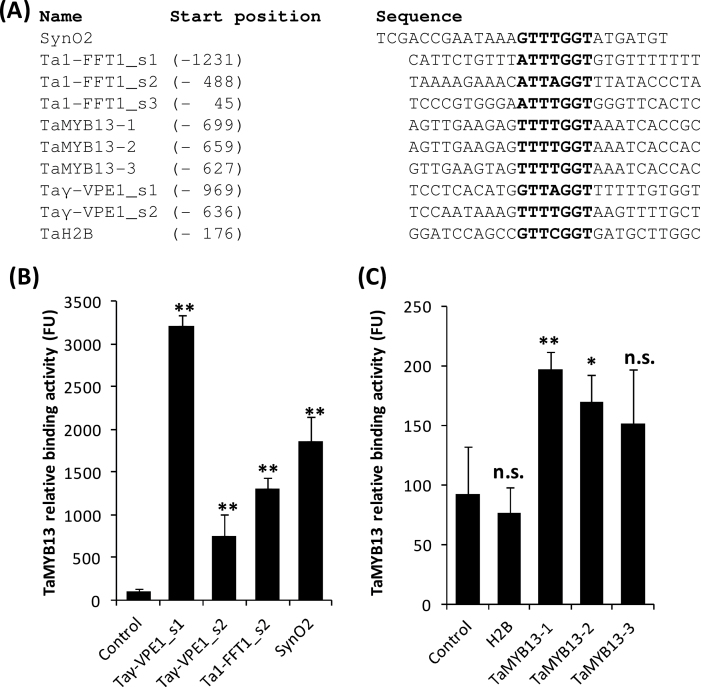

Presence of TaMYB13-binding sites in regulatory regions of target genes

As the TaMYB13-1-upregulated genes in its overexpressing transgenic plants can be direct or indirect target genes, this work investigated whether TaMYB13-1-binding sites were present in their promoter sequences as a supporting line of evidence for directly targeted genes. In the case of Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT, Xue et al. (2011a) have shown that TaMYB13-binding sites are present in the regulatory regions of these genes. The wheat genome sequence database in the CerealsDB website (Wilkinson et al., 2012) was used to identify the regulatory regions of the genes that were upregulated in the transgenic lines. The obtained sequences and probable gene structures were assembled from accessions, as displayed in Supplementary Table S2.

This work was able to identify the regulatory regions of 11 genes (Table 3), in addition to the regulatory regions of Ta1-SST, Ta1-FFT1, Ta6-SFT1, and Ta6-SFT2, which were published previously (Nagaraj et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2010; Xue et al., 2011a). The length of the upstream regulatory regions identified ranged from 0.6 to 2kb (Table 3). Most of these newly identified genes contained at least one core TaMYB13 DNA-binding sequence motif (DTTHGGT; Xue et al., 2011a) in their upstream regulatory regions. In addition to the presence of TaMYB13-binding motifs in the promoter regions of Ta1-SST, Ta6-SFT1, and Ta6-SFT2 (Xue et al., 2011a), Ta1-FFT1 contained three predicted TaMYB13-binding motifs in its upstream regulatory region and Taγ-VPE1 had two predicted motifs.

Table 3.

TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs found in the regulatory regions of TaMYB13-1 target genes

Seq Length is the length of the upstream regulatory region sequence that this study was able to identify. MBS URS displays the number of predicted TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs found in the upstream regulatory region and MBS Intron displays the number of predicted TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs in introns. Accessions of sequences assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB can be found in Supplemental Table S2.

| Target | Accession number | Seq length | MBS URS | MBS Intron |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta1-FFT1 | FJ361762 | 1425 | 3 | 0 |

| Ta1-SST | FJ228689 | 2244a | 2a | ND |

| Ta6-SFT1 | HQ738531 | 850a | 3a | ND |

| Ta6-SFT2 | HQ738530 | 1001a | 4a | ND |

| TaMYB13-1 | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 760 | 1 | 1 |

| TaMYB13-2 | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 762 | 1 | 1 |

| TaMYB13-3 | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 752 | 1 | 1 |

| Putative histone H2B | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 960 | 1 | 0 |

| Ubiquitin-protein ligase | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 622 | 0 | 1 |

| Taγ-VPE1 | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1140 | 2 | 5 |

| Putative amino acid permease | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1061 | 0 | 5 |

| TaFK1 | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1209 | 0 | 4 |

| MYB transcription factor | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1918 | 1 | 0 |

| IAA31-auxin-responsive Aux/IAA family member | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1172 | 0 | 1 |

| CCT motif family protein | Assembled from sequence data in CerealsDB | 1831 | 1 | 3 |

| a Previously published by Xue et al. (2011a). ND, not determined. | ||||

Several genes are known to be regulated by sequences that are present in their introns, for example AGAMOUS and SEEDSTICK (Deyholos and Sieburth, 2000; Kooiker et al., 2005). Therefore, this work searched for TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs in the introns of the identified genes as well. As shown in Table 3, at least one binding site was present in the introns of nine of the analysed genes and three of them (TaFK1, Taγ-VPE1, and amino acid permease) even had four or more of these motifs in their introns.

TaMYB13 binding to target genes

Xue et al. (2011a) have shown that flanking regions play an important role in the determination of the binding affinity of TaMYB13-1. Therefore, CELD reporter-based in vitro DNA-binding assays were performed to determine the affinity of TaMYB13-1 to the identified motifs in the upstream regulatory regions of the following upregulated genes: Ta1-FFT1 (one site), TaMYB13-1 (one site), TaMYB13-2 (one site), TaMYB13-3 (one site), TaH2B (one site), and Taγ-VPE1 (two sites) (Fig. 4) and oligonucleotides 10bp upstream and downstream of the core sequence of TaMYB13 DNA-binding motif were designed. As shown in Fig. 4, TaMYB13-1 bound strongly to the motifs present in the upstream regulatory regions of Ta1-FFT1 and Taγ-VPE1. The strongest interaction was the motif present in the promoter of Taγ-VPE1 site 1 at –969 (Fig. 4B), which was bound by TaMYB13-1 even stronger than SynO2, an in vitro TaMYB13-selected binding sequence (Xue et al., 2011a), which was used as a positive control. In addition, TaMYB13-1 was also able to bind weakly to the motifs present in the upstream regulatory regions of TaMYB13-1, TaMYB13-2 and TaMYB13-3 (Fig. 4C). No binding activity of TaMYB13-1 for the motif present in the H2B promoter region was found (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

In vitro DNA-binding assays of predicted TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs present in the promoter regions of newly identified target genes and TaMYB13 genes. (A) Predicted TaMYB13-1 DNA-binding sites in the upstream regulatory regions of Ta1-FFT1, Taγ-VPE1, TaH2B, and TaMYB13, based on the core TaMYB13-1-binding sequence (DTTHGGT, where D = A, G, or T; H = A, C, or T). SynO2 is an in vitro TaMYB13-1-selected motif. (B, C) In vitro DNA-binding assays determining the binding of TaMYB13-1 to the predicted motifs. Relative TaMYB13-1-binding activity was measured as fluorescence unit (FU) released from the cleavage of methylumbelliferyl β-d-cellulobioside by CELD fused to TaMYB13-1 after 3h of incubation at 40 °C. Displayed values are means ± SD of three replicates. Control is an oligo that does not contain TaMYB13-1-binding motifs; SynO2 was used as a positive control. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

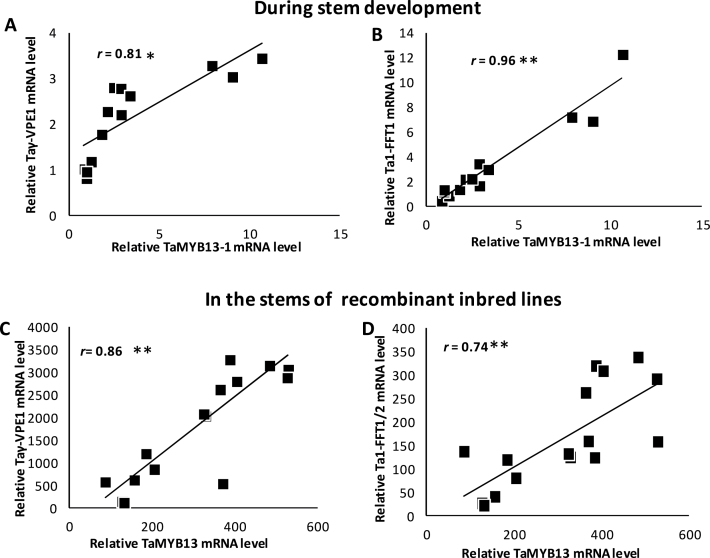

Expression profiles of TaMYB13-1 and its target genes are positively correlated during stem development and in recombinant inbred lines

Because the expression of a positive regulator and its target genes is generally correlated, this work examined the relationship between the expression levels of TaMYB13-1 and the new target genes identified in this study (Ta1-FFT1 and Taγ-VPE1) in developing stems (5 days before anthesis to 10 days after anthesis). Similarly to TaMYB13-1, both Ta1-FFT1 and Taγ-VPE1 transcript levels were markedly upregulated in the top internode (peduncle) at the stem developmental period examined (data not shown). High correlations were observed between the expression levels of TaMYB13-1 and its target genes Taγ-VPE1 and Ta1-FFT1 (Fig. 5A and B). These high expression correlations are similar to those seen between TaMYB13-1 and Ta1-SST or Ta6-SFT genes (Xue et al., 2011a).

Fig. 5.

Correlation in expression between TaMYB13-1 and Ta1-FFT or Taγ-VPE1 in developing stems and in the stems of recombinant inbred lines. (A, B) Expression correlation in developing stems analysed by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. (C, D) Expression correlation in the stems of recombinant inbred lines from Affymterix wheat genome array GSE9767 data, deposited at the NCBI GEO website by Xue et al. (2008b). The probesets used for analysis are: Ta.30798.3.S1_at (Taγ-VPE1), Ta.3475.2.S1_at (Ta1-FFT1 and Ta1-FFT2), and Ta.12834.1.S1_s_at (TaMYB13-1, TaMYB13-2 and TaMYB13-3). Values are Affymetrix array hybridization signals.

To further investigate the expression correlation between TaMYB13-1 and Ta1-FFT1 or Taγ-VPE1, the Affymterix wheat genome array GSE9767 data, deposited at the NCBI GEO website by Xue et al. (2008b) was analysed using eight independent recombinant inbred lines with two field replicates per line (16 samples) to investigate their relationships. High correlations were found between the hybridization signal levels of the TaMYB13 probeset and the targets Taγ-VPE1 or Ta1-FFT (Fig. 5C and D).

Yield-related phenotypes of transgenic lines overexpressing TaMYB13-1 under mild water-deficit conditions

WSC levels in wheat are known to be positively associated with grain yield under terminal drought conditions (Aggarwal and Sinha, 1984; van Herwaarden et al., 1998b; Xue et al., 2008b). Therefore, this work examined the yield-related phenotypes of transgenic plants at T5 generation grown under mild water-deficit conditions in comparison with Bobwhite control plants. As shown in Table 4, the transgenic lines (a20, a21, and b2) had increased values for all measured traits, although not all increases were statistically significant. The most prominent increase was observed in the total grain weight per plant, but this increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.09). Significant increases were observed for the top spike weight, average spike weight, and grain weight per spike.

Table 4.

Yield-related phenotypes of TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic wheat

Values shown are means ± SD (n = 3). Pots of 14.3-l capacity with a 29-cm top diameter were used for growing transgenic plants (three pots) and wild-type Bobwhite (three pots). Each pot grew six plants. The plants were grown under a mild water-deficit regime. Individual phenotypic data derived from each pot were used for calculation of the mean values of each group. For TaMYB13-1 transgenic lines, mean values are derived from three independent transgenic lines (a20, a21, and b2) at the T5 stage.

| Phenotype | TaMYB13-1 transgenic lines | Bobwhite control | P-value | % increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiller number/plant | 11.7±0.67 | 11.5±0.44 | 0.74 | 1.7 |

| Total spike weight/plant (g) | 36.6±3.63 | 32.9±1.01 | 0.17 | 11.2 |

| Total grain weight/plant (g) | 28.8±2.47 | 25.5±0.44 | 0.09 | 12.9 |

| Top spike weight (g) | 4.22±0.25 | 3.80±0.04 | 0.05 | 11.1 |

| Average spike weight (g) | 3.14±0.16 | 2.87±0.05 | 0.05 | 9.4 |

| Grain weight/spike (g) | 2.47±0.09 | 2.23±0.07 | 0.02 | 10.8 |

| Hundred grain weight (g) | 4.80±0.19 | 4.70±0.18 | 0.51 | 2.1 |

| Total grain number/plant | 600±67 | 547±27 | 0.27 | 9.7 |

Discussion

Investigation of regulatory networks involved in controlling fructan synthesis associated genes, which include fructosyltransferases and their modification and processing enzymes, in plants is an important topic of research. It will lead to understand the regulatory pathways of fructan synthesis and the critical genes associated with the high fructan accumulation trait in temperate cereals, as well as to facilitate future genetic manipulation of fructan accumulation for human health benefit of higher fructan plant products (Roberfroid, 2007) and potential improvement of crop yield in abiotic stress-prone environments. TaMYB13-1 has been shown to be a transcriptional activator of Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT in wheat using a transient transactivation system. This study showed that overexpression of TaMYB13-1 in transgenic wheat resulted not only in increased expression levels of the genes directly involved in or associated with fructan synthesis, but also in increased fructan and WSC concentrations in transgenic wheat lines, thus demonstrating that TaMYB13-1 mediates the coordinated regulation of a major set of genes involved in fructan synthesis.

Affymetrix array expression analysis revealed that 27 genes were upregulated at least 2-fold in the leaves of TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic lines compared to Bobwhite control plants. All Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT genes represented by the probesets in the Affymetrix wheat genome array (Ta1-SST2, Ta6-SFT1, and Ta6-SFT2) were found to be upregulated in the transgenic lines, which supports the proposed TaMYB13-1 regulatory role based on the transient transactivation data (Xue et al., 2011a). Most interestingly, two probesets that belong to Ta1-FFT genes, the third family of fructosyltransferases, were also upregulated in TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines. This is one of the novel TaMYB13-1 target genes identified in this study, as the regulation of this family of fructosyltransferases by TaMYB13-1 was not investigated in the previous study (Xue et al., 2011a).

Correlation analysis also showed that the expression levels of these three families of fructosyltransferase genes (Ta1-SST, Ta6-SFT, and Ta1-FFT) were highly correlated with TaMYB13-1 expression among the sample set of transgenic lines and Bobwhite control plants, as well as among samples obtained from various stem developmental stages (Xue et al., 2011a; this study). It has been shown that the expression profiles of Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT genes are positively correlated with that of TaMYB13-1 in recombinant inbred lines (Xue et al., 2011a). Correlation analysis of the Affymetrix data previously deposited by Xue et al. (2008b) showed that the expression of the Ta1-FFT probeset (Ta.3475.2.S1_at, which hybridizes with both Ta1-FFT1 and Ta1-FFT2) was also positively correlated with that of the TaMYB13 probeset in the stem of recombinant inbred SB lines. The correlation coefficients between TaMYB13-1 and Ta1-FFT1 in the flag leaf and stem in the datasets of the transgenic and control plants were very high. This high correlation was also observed during stem development. The fact that there were very high expression correlations between TaMYB13-1 and Ta1-FFT1 in various genetic backgrounds as well as during stem development makes it likely that Ta1-FFT1 is also a direct target of TaMYB13-1. To further support this, TaMYB13-1 was able to bind strongly to a motif present in the upstream regulatory region of Ta1-FFT1 in in vitro DNA-binding assays.

In addition to genes that are directly involved in the fructan synthetic pathway, two genes (Taγ-VPE1 and TaFK1) were found to be upregulated in the leaf of TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines and could be linked indirectly to this pathway. TaFK1 was upregulated about 2.4-times in the leaves of transgenic lines, indicating a role of TaMYB13-1 in the regulation of the fructose metabolism. Fructokinases (EC 2.7.1.4) catalyse the conversion of fructose to d-fructose-6-phosphate and have been shown to be induced upon the external application of fructose, glucose, and sucrose in tomato (Schaffer and Petreikov, 1997). Davies et al. (2005) have shown that in potato fructokinases are able to balance sucrose synthesis and metabolism in concert with sucrose synthase, which converts sucrose into fructose and UDP-d-glucose. Free fructose can also come from sucrose hydrolysis by invertase as well as from fructan exohydrolase trimming of fructans as a part of the fructan synthesis process (Bancal et al., 1992; Van den Ende et al., 2003; Lothier et al., 2007). The increased demand for sucrose in the cells that express the elevated levels of fructosyltransferases might be partly offset by the increase in fructokinase, since the product of this enzyme, d-fructose-6-phosphate, is a substrate for sucrose-phosphate synthase. Therefore, an increase in fructokinase would favour carbon flow towards fructan accumulation. However, it is unclear if this regulation is direct or indirect, since this work was not able to find any TaMYB13-binding motifs in the upstream regulatory region of this gene. However, there were three TaMYB13-binding motifs present in the first intron of this gene, so the direct regulation of this gene by TaMYB13-1 cannot be excluded. The expression of TaMYB13-1 and TaFK1 in the leaf correlates significantly in the dataset of the transgenic versus control plants, but was not statistically significant in the stem, which indicates that the expression of TaFK1 in the stem might be regulated predominantly by other transcription factors.

The other TaMYB13-1-upregulated gene that might be indirectly linked to the fructan synthesis is Taγ-VPE1, which may be involved in processing vacuolar fructosyltransferase proteins. VPE proteins are vacuolar cysteine proteases, known to cleave natural substrates in plants after asparagine residues and involved in processing the maturation or degradation of many vacuolar proteins (Yamada et al., 2005; Tsiatsiani et al., 2012). Known natural substrates of plant VPEs include storage proteins, vacuolar invertase, and carboxypeptidase Y (Hara-Nishimura et al., 1991; Shimada et al., 2003; Tsiatsiani et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, four VPEs have been identified that are partially redundant in storage protein cleavage (Gruis et al., 2004). Some VPEs have also been reported to play a role in programmed cell death (Hayashi et al., 2001; Rojo et al., 2004; Hara-Nishimura and Hatsugai, 2011). Several groups have shown that fructosyltransferases in planta generally consist of two subunits generated from the cleavage of fructosyltransferase pre-proteins (Sprenger et al., 1995; Koops and Jonker, 1996; Van den Ende et al., 1996, 2000). Sprenger et al. (1995) reported that the cleavage of barley 6-SFT (Hv6-SFT) occurs between Asn and an EAD triplet. This cleavage site fits into the substrate specificity of VPEs. Wheat Ta1-SST and Ta6-SFT pre-proteins contain the cleavage site of NEAD, whereas Ta1-FFT pre-proteins have a similar site: NEVD. From the recent review on the natural substrates of plant proteases (Tsiatsiani et al., 2012), it appears that only VPEs cleave the Asn–other amino acid residue bond in natural substrates known to date. Although the uncleaved version of a number of recombinant fructosyltransferases expressed in Pichia pastoris is functional (Lüscher et al., 2000; Altenbach et al., 2004; Van den Ende et al., 2006, 2011; Lasseur et al., 2011), some plant fructosyltransferases expressed in the yeast showed almost undetectable activities (Hisano et al., 2008; Lasseur et al., 2011). It is likely that this cleavage is necessary for increase in activity in planta or stability of fructosyltransferase proteins in the vacuole.

Analysis of the Affymetrix data of recombinant inbred lines showed that the expression of Taγ-VPE1 was highly correlated with the expression of TaMYB13-1 in recombinant inbred lines. Significant correlation was observed in the developing stem samples and in the transgenic/control plant datasets. Interestingly, the upstream regulatory region of this gene contains two motifs and one of them was bound very strongly by TaMYB13-1 in in vitro DNA-binding assays, indicating that this gene is likely to be directly regulated by TaMYB13-1. Close expression correlations were found between Taγ-VPE1 and fructosyltransferase genes in the stem in all expression datasets. Close co-regulation of Taγ-VPE1 with fructosyltransferase genes within the TaMYB13-1 regulatory network together with the cleavage sites of fructosyltransferases fitting into the substrate specificity of Taγ-VPE1 point to the potential involvement of Taγ-VPE1 in processing the maturation of fructosyltransferases in the vacuole in wheat. These findings will lead to a new exciting research topic on the potential role of γ-VPE1 in modulating fructan accumulation by its ability in potential enhancement of fructosyltransferase activity as discussed above.

Although TaMYB13-1 is highly expressed in organs where fructans accumulate at high levels, it is also expressed in other organs where fructan synthetic activity is low, such as mature leaf. In particular, the highly homologous genes of TaMYB13 exist in non-fructan accumulating plant species such as Arabidopsis and rice. For example, the TaMYB13 homologue in Arabidopsis, AtMYB59, is involved in root growth and cell cycle (Mu et al., 2009). Therefore, it is likely that TaMYB13-1 also plays a role in regulation of other processes. Mu et al. (2009) published a list of upregulated genes in transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpresses AtMYB59. Although the promoters used for driving the expression of AtMYB59 and TaMYB13-1 were different (cauliflower mosaic virus 35S vs. Hv6-SFT) and the organ used in their study was also different from the organ used in this study (flag leaf vs. 12-day-old seedlings), this work was able to find nine genes that had an increased expression in both datasets (Supplementary Table S3). The upregulation of these common genes was relatively small, ranging from 1.21 to 2.42-times higher in TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines than the control plants, but statistically significant (P < 0.05). This work was also able to find multiple core TaMYB13 DNA-binding motifs in the upstream regulatory region and/or introns of all these common targets in Arabidopsis (data not shown) except for At4g25630 and At5g60520. However, as the levels of the increase in the expression of most of these genes in the TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines were low, it is likely that TaMYB13-1 plays only a minor role in the regulation of these genes. It is also interesting to see that TaMYB13-1 is able to bind to its own regulatory region, indicating a potential feedback loop, although its affinity to the motif was very low. Feedback loops have been reported previously for MYB transcription factors, such as CCA1 in Arabidopsis (Wang and Tobin, 1998).

It appears that an increase in the expression level of a single regulator has an impact on fructan and WSC accumulation. A significant increase in fructan and WSC concentrations was found in the leaf and top internode of TaMYB13-1-overexpressing lines, compared to wild-type control plants. The increase of fructans in these two organs was 2.2-fold in the flag leaf, and 15.4-fold in the top internode. WSC levels in these organs were also significantly increased in the transgenic lines. This increase was largely attributed to the enhanced accumulation of the fructan component of the WSCs. These data are in line with results that there is a high correlation between TaMYB13-1 expression levels and WSC or fructan levels in recombinant inbred lines (Xue et al., 2011a). In fact, in the datasets of the transgenic lines and control plants, very high correlations were observed between the levels of TaMYB13-1 mRNA and WSC or fructan in both the flag leaf and the top internode.

WSC levels and wheat yield under terminal drought conditions are known to be positively associated. The overexpression of TaMYB13-1 in transgenic plants resulted in an increase in spike weight and grain weight per spike under mild water-limited conditions. It is likely that the increased grain weight per spike in the transgenic plants is attributed to the enhanced accumulation of fructans in the stem, which supplies the increased amount of carbon reserve to the spike for grain filling. In addition, the grain weight per plant was increased by 13%, although the difference was not significant at the P-value level of 0.05. In view of that the contribution of the stored fructan to grain yield under terminal drought environments can also be attributed to the levels of fructan hydrolysis enzymes (fructan exohydrolases) during the fructan remobilization phase (Joudi et al., 2012), simultaneous manipulation of fructan exohydrolases may further improve grain yield through enhancing fructan remobilization.

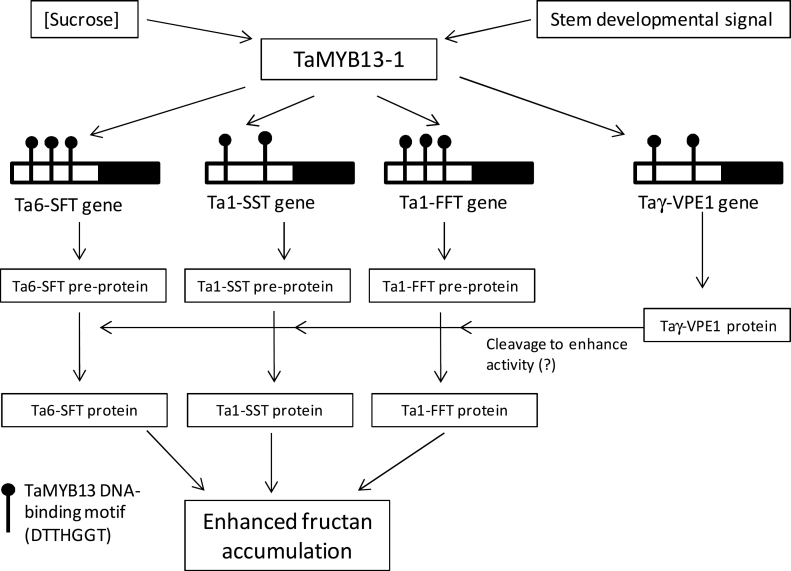

In summary, this study clearly demonstrates that TaMYB13-1 can act as a positive regulator for regulation of all three families of fructosyltransferase genes (including Ta1-FFT), which are directly involved in the fructan synthetic pathway in wheat. TaMYB13-1 regulates the fructan synthetic pathway by direct binding to the regulatory regions of fructosyltransferase genes. This TaMYB13-1 regulatory network is upregulated by sucrose and stem developmental signal (Xue et al., 2011a), although besides sucrose what other factor is responsible for triggering fructan accumulation during stem development in wheat is still unclear. TaMYB13-1 is also involved in direct upregulation of Taγ-VPE1 through the binding to its promoter and Taγ-VPE1 may be involved in processing the maturation of fructosyltransferases for enhancing their activities. The currently proposed regulatory model of TaMYB13-1 is illustrated in Fig. 6. Together, these genes form a regulon for modulating fructan accumulation in the vacuole, which is mediated by the sucrose signalling pathway that involves protein kinases and phosphatases as previously reported (Martínez-Noël et al., 2001, 2009; Kusch et al., 2009; Ritsema et al., 2009). Whether involvement of these protein kinases and phosphatases in regulating the fructan synthesis is via the modification of TaMYB13-1 activity awaits future investigation, as the post-translational modification of transcription factors is a common mechanism in gene regulation, such as plant bZIP factors (Schütze et al., 2008). It appears that overexpression of TaMYB13-1 in transgenic wheat is sufficient to increase fructan concentrations in the leaf and stem. However, further studies are required to see whether an increase in fructan accumulation through overexpression of TaMYB13-1 is able to improve grain yield in terminal abiotic stress environments in the field, such as drought and heat stress at the reproductive stage of wheat.

Fig. 6.

Illustration of the proposed regulatory model of TaMYB13-1 for fructan synthesis in temperate cereals. The TaMYB13-binding sites in Ta6-SFT1, Ta1-SST, Ta1-FFT1, and Taγ-VPE1 promoters are indicated. The γ-VPE protein might be involved in the maturation of fructosyltransferases in the vacuole by cleavage of the fructosyltransferase pre-proteins into two subunits (mature fructosyltransferases).

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Probesets that are downregulated at least 2-fold in TaMYB13-1-overexpressing transgenic lines compared to Bobwhite control plants.

Supplementary Table S2. Accession numbers of sequences used to assemble the genomic sequences of genes that are upregulated by TaMYB13-1 obtained by blast search in the wheat genome sequence database of CerealsDB.

Supplementary Table S3. Common upregulated target genes between TaMYB13-1 (this study) and AtMYB59-overexpressing transgenic plants.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Correlation in expression between Taγ-VPE1 and fructosyltransferase genes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship grant from CSIRO Office of Chief Executive. The authors would like to thank Dr P. Joyce for her kind help in wheat transformation and Terry Grant for his support in management of the controlled environment facility and plant growth.

References

- Aggarwal PK, Sinha SK. 1984. Effect of water stress on grain growth and assimilate partitioning in two cultivars of wheat contrasting in their yield stability in a drought-environment. Annals of Botany 53, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Altenbach D, Nüesch E, Meyer AD, Boller T, Wiemken A. 2004. The large subunit determines catalytic specificity of barley sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase and fescue sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase. FEBS Letters 567, 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenbach D, Rudino-Pinera E, Olvera C, Boller T, Wiemken A, Ritsema T. 2009. An acceptor-substrate binding site determining glycosyl transfer emerges from mutant analysis of a plant vacuolar invertase and a fructosyltransferase. Plant Molecular Biology 69, 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asseng S, van Herwaarden AF. 2003. Analysis of the benefits to wheat yield from assimilates stored prior to grain filling in a range of environments. Plant and Soil 256, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Austin RB, Edrich JA, Ford MA, Blackwell RD. 1977. The fate of the dry matter, carbohydrates and 14C lost from the leaves and stems of wheat during grain filling. Annals of Botany 41, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Bancal P, Carpita NC, Gaudillere JP. 1992. Differences in fructan accumulated in induced and field-grown wheat plants: an elongation-trimming pathway for their synthesis. New Phytologist 120, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow W, Darbyshire B, Pheloung P. 1984. Fructans polymerised and depolymerised in the internodes of winter wheat as grain-filling progressed. Plant Science Letters 36, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bolouri-Moghaddam MR, Le Roy K, Xiang L, Rolland F, Van den Ende W. 2010. Sugar signalling and antioxidant network connections in plant cells. FEBS Journal 277, 2022–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett GD, Incoll LD. 1992. The potential pre-anthesis and post-anthesis contributions of stem internodes to grain yield in crops of winter barley. Annals of Botany 69, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett GD, Incoll LD. 1993. Effects on the stem of winter barley of manipulating the source and sink during grain-filling. Journal of Experimental Botany 44, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J, Lidgett A, Cummings N, Cao Y, Forster J, Spangenberg G. 2005. Molecular genetics of fructan metabolism in perennial ryegrass. Plant Biotechnology Journal 3, 459–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwen CW, John P. 1989. Localization of the enzymes of fructan metabolism in vacuoles isolated by a mechanical method from tubers of Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.). Plant Physiology 89, 658–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies HV, Shepherd LVT, Burrell MM, et al. 2005. Modulation of fructokinase activity of potato (Solanum tuberosum) results in substantial shifts in tuber metabolism. Plant Cell Physiology 46, 1103–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Halleux S, Cutsem PV. 1997. The electronic Plant Gene Register. Plant Physiology 113, 1003–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demel RA, Dorrepaal E, Ebskamp MJ, Smeekens JC, de Kruijff B. 1998. Fructans interact strongly with model membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1375, 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyholos MK, Sieburth LE. 2000. Separable whorl-specific expression and negative regulation by enhancer elements within the AGAMOUS second intron. The Plant Cell 12, 1799–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes MJ, Scott RK, Sylvester-Bradley R. 2002. The ability of wheat cultivars to withstand drought in UK conditions: formation of grain yield. Journal of Agricultural Science 138, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, She MY, Yin GX, Yu Y, Qiao WH, Du LP, Ye XG. 2010. Cloning and characterization of genes coding for fructan biosynthesis enzymes (FBEs) in Triticeae plants. Agricultural Sciences in China 9, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Gruis D, Schulze J, Jung R. 2004. Storage protein accumulation in the absence of the vacuolar processing enzyme family of cysteine proteases. The Plant Cell 16, 270–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Nishimura I, Hatsugai N. 2011. The role of vacuole in plant cell death. Cell Death and Differentiation 18, 1298–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Nishimura I, Inoue K, Nishimura M. 1991. A unique vacuolar processing enzyme responsible for conversion of several proprotein precursors into the mature forms. FEBS Letters 294, 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Yamada K, Shimada T, Matsushima R, Nishizawa NK, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. 2001. A proteinase-storing body that prepares for cell death or stresses in the epidermal cells of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiology 42, 894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwege EM, Gritscher D, Willmitzer L, Heyer AG. 1997. Transgenic potato tubers accumulate high levels of 1-kestose and nystose: functional identification of a sucrose sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase of artichoke (Cynara scolymus) blossom discs. The Plant Journal 12, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry G. 1987. The ecological significance of fructan in a contemporary flora. New Phytologist 106, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hincha DK, Hellwege EM, Heyer AG, Crowe JH. 2000. Plant fructans stabilize phosphatidylcholine liposomes during freeze-drying. European Journal of Biochemistry 267, 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano H, Kanazawa A, Yoshida M, Humphreys MO, Iizuka M, Kitamura K, Yamada T. 2008. Coordinated expression of functionally diverse fructosyltransferase genes is associated with fructan accumulation in response to low temperature in perennial ryegrass. New Phytologist 178, 766–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incoll L, Bonnett G, Gott B. 1989. Fructans in the underground storage organs of some australian plants used for food by Aborigines. Journal of Plant Physiology 134, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Joudi M, Ahmadi A, Mohamadi V, Abbasi A, Vergauwen R, Mohammadi H, Van den Ende W. 2012. Comparison of fructan dynamics in two wheat cultivars with different capacities of accumulation and remobilization under drought stress. Physiologia Plantarum 144, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam J, Gresshoff PM, Shorter R, Xue GP. 2008. The Q-type C2H2 zinc finger subfamily of transcription factors in Triticum aestivum is predominantly expressed in roots and enriched with members containing an EAR repressor motif and responsive to drought stress. Plant Molecular Biology 67, 305–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami A, Sato Y, Yoshida M. 2008. Genetic engineering of rice capable of synthesizing fructans and enhancing chilling tolerance. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami A, Yoshida M. 2002. Molecular characterization of sucrose: sucrose 1- fructosyltransferase and sucrose: fructan 6-fructosyltransferase associated with fructan accumulation in winter wheat during cold hardening. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry 66, 2297–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami A, Yoshida M. 2005. Fructan:fructan 1-fructosyltransferase, a key enzyme for biosynthesis of graminan oligomers in hardened wheat. Planta 223, 90–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooiker M, Airoldi CA, Losa A, Manzotti PS, Finzi L, Kater MM, Colombo L. 2005. BASIC PENTACYSTEINE1, a GA-binding protein that induces conformational changes in the regulatory region of the homeotic Arabidopsis gene SEEDSTICK. The Plant Cell 17, 722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koops AJ, Jonker HH. 1994. Purification and characterization of the enzymes of fructan biosynthesis in tubers of Helianthus tuberosus ‘Colombia.’ I. Fructan:fructan fructosyltransferase. Journal of Experimental Botany 45, 1623–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koops AJ, Jonker HH. 1996. purification and characterization of the enzymes of fructan biosynthesis in tubers of Helianthus tuberosus Colombia (II. Purification of sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase and reconstitution of fructan synthesis in vitro with purified sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase and fructan:fructan 1-fructosyltransferase). Plant Physiology 110, 1167–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA, Tomos AD, Farrar JF, Gallagher J, Pollock CJ. 2001. Carbon allocation and sugar status in individual cells of barley leaves affects expression of sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase gene. Annals of Applied Biology 138, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kusch U Greiner S Steininger H Meyer AD Corbière-Divialle H Harms K Rausch T 2009. Dissecting the regulation of fructan metabolism in chicory (Cichorium intybus) hairy roots. New Phytologist 184, 127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammens W, Le Roy K, Yuan S, Vergauwen R, Rabijns A, Van Laere A, Strelkov SV, Van den Ende W. 2012. Crystal structure of 6-SST/6-SFT from Pachysandra terminalis, a plant fructan biosynthesizing enzyme in complex with its acceptor substrate 6-kestose. Plant Journal 70, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasseur B, Lothier J, Djoumad A, De Coninck B, Smeekens S, Van Laere A, Morvan-Bertrand A, Van den Ende W, Prud’homme MP. 2006. Molecular and functional characterization of a cDNA encoding fructan:fructan 6G-fructosyltransferase (6G-FFT)/fructan:fructan 1-fructosyltransferase (1-FFT) from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 2719–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasseur B, Lothier J, Wiemken A, Van Laere A, Morvan-Bertrand A, Van den Ende W, Prud’homme MP. 2011. Towards a better understanding of the generation of fructan structure diversity in plants: molecular and functional characterization of a sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase (6-SFT) cDNA from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 1871–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothier J, Lasseur B, Le Roy K, Van Laere A, Prud’homme MP, Barre P, Van den Ende W, Morvan-Bertrand A. 2007. Cloning, gene mapping, and functional analysis of a fructan 1-exohydrolase (1-FEH) from Lolium perenne implicated in fructan synthesis rather than in fructan mobilization. Journal of Experimental Botany 58, 1969–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston DP, Hincha DK, Heyer AG. 2009. Fructan and its relationship to abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 66, 2007–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Koroleva OA, Farrar JF, Gallagher J, Pollock CJ, Tomos AD. 2002. Rubisco small subunit, chlorophyll a/b-binding protein and sucrose:fructan-6-fructosyltransferase gene expression and sugar status in single barley leaf cells in situ. cell type specificity and induction by light. Plant Physiology 130, 1335–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher M, Erdin C, Sprenger N, Hochstrasser U, Boller T, Wiemken A. 1996. Inulin synthesis by a combination of purified fructosyltransferases from tubers of Helianthus tuberosus. FEBS Letters 385, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher M, Hochstrasser U, Vogel G, Aeschbacher R, Galati V, Nelson CJ, Boller T, Wiemken A. 2000. Cloning and functional analysis of sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase from tall fescue. Plant Physiology 124, 1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Noël G, Tognetti JA, Pontis HG. 2001. Protein kinase and phosphatase activities are involved in fructan synthesis initiation mediated by sugars. Planta 213, 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Noël GA, Tognetti JA, Salerno GL, Pontis HG. 2010. Sugar signaling of fructan metabolism: new insights on protein phosphatases in sucrose-fed wheat leaves. Plant Signalling and Behaviour 5, 311–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Noël GMA, Tognetti JA, Salerno GL, Wiemken A, Pontis HG. 2009. Protein phosphatase activity and sucrose-mediated induction of fructan synthesis in wheat. Planta 230, 1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CL, Casu RE, Rattey A, Dreccer MF, Kam JW, van Herwaarden AF, Shorter R, Xue GP. 2011. Linked gene networks involved in nitrogen and carbon metabolism and levels of water soluble carbohydrate accumulation in wheat stems. Functional and Integrative Genomics 11, 585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CL, Seung D, Casu RE, Rebetzke GJ, Shorter R, Xue GP. 2012. Genotypic variation in the accumulation of water soluble carbohydrates in wheat. Functional Plant Biology 39, 560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu R-L, Cao Y-R, Liu Y-F, et al. 2009. An R2R3-type transcription factor gene AtMYB59 regulates root growth and cell cycle progression in Arabidopsis. Cell Research 19, 1291–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Aeschbacher RA, Sprenger N, Boller T, Wiemken A. 2000. Disaccharide-mediated regulation of sucrose:fructan-6-fructosyltransferase, a key enzyme of fructan synthesis in barley leaves. Plant Physiology 123, 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj VJ, Altenbach D, Galati V, Lüscher M, Meyer AD, Boiler T, Wiemken A. 2004. Distinct regulation of sucrose: sucrose-1-fructosyltransferase (1-SST) and sucrose: fructan-6-fructosyltransferase (6-SFT), the key enzymes of fructan synthesis in barley leaves: 1-SST as the pacemaker. New Phytologist 161, 735–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj VJ, Riedl R, Boller T, Wiemken A, Meyer AD. 2001. Light and sugar regulation of the barley sucrose: fructan 6-fructosyltransferase promoter. Journal of Plant Physiology 158, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrineschi A, Noguera LM, Skovmand B, Brito RM, Velazquez L, Salgado MM, Hernandez R, Warburton M, Hoisington D. 2002. Identification of highly transformable wheat genotypes for mass production of fertile transgenic plants. Genome 45, 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits EAH, Ebskamp MJM, Paul MJ, Jeuken MJW, Weisbeek PJ, Smeekens SCM. 1995. Improved performance of transgenic fructan-accumulating tobacco under drought stress. Plant Physiology 107, 125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ. 1984. Sucrose accumulation and the initiation of fructan biosynthesis in Lolium temulentum L. New Phytologist 96, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ. 1986. Transley review. No. 5 fructans and the metabolism of sucrose in vascular plants. New Phytologist 104, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsema T, Brodmann D, Diks SH, Bos CL, Nagaraj V, Pieterse CMJ, Boller T, Wiemken A, Peppelenbosch MP. 2009. Are small GTPases signal hubs in sugar-mediated induction of fructan biosynthesis? PLoS One 4, e6605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsema T, Smeekens S. 2003a. Fructans: beneficial for plants and humans. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 6, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsema T, Smeekens SCM. 2003b. Engineering fructan metabolism in plants. Journal of Plant Physiology 160, 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberfroid MB. 2007. Inulin-type fructans: functional food ingredients. Journal of Nutrition 137, 2493S–2502S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo E, Martín R, Carter C, et al. 2004. VPEγ exhibits a caspase-like activity that contributes to defense against pathogens. Current Biology 14, 1897–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska SA, Lewis DC, Kennedy G, Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Tabe LM. 2008. Large scale transcriptome analysis of the effects of nitrogen nutrition on accumulation of stem carbohydrate reserves in reproductive stage wheat. Plant Molecular Biology 66, 15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska S, Rebetzke G, van Herwaarden A, Richards R, Fettell N, Tabe L, Jenkins C. 2006. Genotypic variation in water-soluble carbohydrate accumulation in wheat. Functional Plant Biology 33, 799–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer AA, Petreikov M. 1997. Sucrose-to-starch metabolism in tomato fruit undergoing transient starch accumulation. Plant Physiology 113, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütze K, Harter K, Chaban C. 2008. Post-translational regulation of plant bZIP factors. Trends in Plant Science 13, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, McIntyre CL, Gresshoff PM, Xue GP. 2009. Members of the Dof transcription factor family in Triticum aestivum are associated with light-mediated gene regulation. Functional and Integrative Genomics 9, 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Yamada K, Kataoka M, et al. 2003. Vacuolar processing enzymes are essential for proper processing of seed storage proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, 32292–32299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger N, Bortlik K, Brandt A, Boller T, Wiemken A. 1995. Purification, cloning, and functional expression of sucrose:fructan 6-fructosyltransferase, a key enzyme of fructan synthesis in barley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 92, 11652–11656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatsiani L, Gevaert K, Van Breusegem F. 2012. Natural substrates of plant proteases: how can protease degradomics extend our knowledge? Physiologia Plantarum 145, 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valluru R, Van den Ende W. 2008. Plant fructans in stress environments: emerging concepts and future prospects. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 2905–2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Clerens S, Vergauwen R, Boogaerts D, Roy KL, Arckens L, Van Laere A. 2006. Cloning and functional analysis of a high DP fructan:fructan 1-fructosyl transferase from Echinops ritro (Asteraceae): comparison of the native and recombinant enzymes. Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 775–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Clerens S, Vergauwen R, Van Riet L, Van Laere A, Yoshida M, Kawakami A. 2003. Fructan 1-exohydrolases. β-(2,1)-trimmers during graminan biosynthesis in stems of wheat? purification, characterization, mass mapping, and cloning of two fructan 1-exohydrolase isoforms. Plant Physiology 131, 621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Coopman M, Clerens S, Vergauwen R, Le Roy K, Lammens W, Van Laere A. 2011. Unexpected presence of graminan- and levan-type fructans in the evergreen frost-hardy eudicot Pachysandra terminalis (Buxaceae): purification, cloning, and functional analysis of a 6-SST/6-SFT enzyme. Plant Physiology 155, 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Lammens W, Van Laere A, Schroeven L, Le Roy K. 2009. Donor and acceptor substrate selectivity among plant glycoside hydrolase family 32 enzymes. FEBS Journal 276, 5788–5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Michiels A, Wonterghem DV, Vergauwen R, Van Laere A. 2000. Cloning, developmental, and tissue-specific expression of sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyl transferase from Taraxacum officinale. Fructan localization in roots. Plant Physiology 123, 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Valluru R. 2009. Sucrose, sucrosyl oligosaccharides, and oxidative stress: scavenging and salvaging? Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Van Wonterghem D, Dewil E, Verhaert P, De Loof A, Van Laere A. 1996. Purification and characterization of 1-SST, the key enzyme initiating fructan biosynthesis in young chicory roots (Cichorium intybus). Physiologia Plantarum 98, 455–466. [Google Scholar]

- van Herwaarden AF, Angus JF, Richards RA, Farquhar GD. 1998a. ‘Haying-off’, the negative grain yield response of dryland wheat to nitrogen fertilizer II. Carbohydrate and protein dynamics. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 49, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar]

- van Herwaarden AF, Richards RA, Farquhar GD, Angus JF. 1998b. ‘Haying-off’, the negative grain yield response of dryland wheat to nitrogen fertilizer III.The influence of water deficit and heat shock. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 49, 1095–110. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer IM, Koops AJ, Hakkert JC, van Tunen AJ. 1998. Cloning of the fructan biosynthesis pathway of Jerusalem artichoke. The Plant Journal 15, 489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijn I, Van Dijken A, Lüscher M, Bos A, Smeets E, Weisbeek P, Wiemken A, Smeekens S. 1998. Cloning of sucrose:sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase from onion and synthesis of structurally defined fructan molecules from sucrose. Plant Physiology 117, 1507–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijn I, Van Dijken A, Sprenger N, Van Dun K, Weisbeek P, Wiemken A, Smeekens S. 1997. Fructan of the inulin neoseries is synthesized in transgenic chicory plants (Cichorium intybus L.) harbouring onion (Allium cepa L.) fructan:fructan 6G-fructosyltransferase. The Plant Journal 11, 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner W, Wiemken A, Matile P. 1986. Regulation of fructan metabolism in leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv Gerbel). Plant Physiology 81, 444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Tobin EM. 1998. Constitutive expression of the CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) gene disrupts circadian rhythms and suppresses its own expression. Cell 93, 1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw IF, Willenbrink J. 2000. Mobilization of fructan reserves and changes in enzyme activities in wheat stems correlate with water stress during kernel filling. New Phytologist 148, 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PA, Winfield MO, Barker GLA, Allen AM, Burridge A, Coghill JA, Edwards KJ. 2012. CerealsDB 2.0: an integrated resource for plant breeders and scientists. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]