Abstract

Background

Intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-IM) is now available in subcutaneous (SC) formulation, potentially allowing for home-based self-administration. We examined adolescents’ interest in and proficiency at DMPA-SC self-administration.

Study Design

This is a planned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial comparing pain between DMPA-IM and DMPA-SC. In the trial, study participants (N=55) aged 14–21 years were recruited at DMPA initiation and randomized to receive DMPA-IM or DMPA-SC. Participants received the alternate formulation at 3 months, chose formulation at 6 months, and could learn self-administration at 9 months. The current analysis is of the women who chose self-administration of DMPA-SC. Proficiency was rated for each step of self-administration: independently [I], with reassurance [R], with verbal instruction [V], or nurse performed [RN]. Data were analyzed using descriptive and comparative statistics.

Results

Thirty-five percent (19/55) of participants learned self-administration. Proficiency ratings were: chose injection site (I=78.9%, R=5.3%, V=5.3%, RN=10.5%); cleaned site (I=89.5%, RN=10.5%); assembled injection device (I=47.4%, R=36.8%, V=15.8%), self-injected (I=31.6%, R=36.8%, V=15.8%, RN=15.8%), and disposed of device (I=21.1%, R=21.1%, RN=57.9%).

Conclusions

Many adolescents are interested in and capable of DMPA-SC self-administration with brief education and minimal assistance.

Keywords: depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, adolescent, contraception, self-injection

1. Introduction

Intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-IM) is a popular contraceptive choice among adolescent women, and has contributed to the decline in teen pregnancy rates [1]. In 2006–2010, 20.3% of sexually experienced females 15–19 years of age used DMPA-IM, double the rate of DMPA use in 1995 [1, 2]. However, administration of DMPA-IM requires quarterly office visits, with associated costs, time and transportation needs which may serve as a barrier to adherence to follow-up injections. Self-administration would make it possible for young women with limited availability of health care providers, transportation, and financial resources to use this convenient, safe, and reliable contraceptive method.

Subcutaneous DMPA (DMPA-SC) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2005 for use in women of childbearing potential, including adolescents. The FDA approval and medication labeling do not specify who may administer the injection (e.g. provider, pharmacist, patient) or in what setting (e.g. clinic, home) [3]. DMPA-SC was developed with the goals of (a) providing a formulation of DMPA which could be self-administered at home, (b) minimizing side effects through dose reduction (104 mg DMPA-SC versus 150 mg DMPA-IM), (c) hastening the return to cyclic ovulation after DMPA discontinuation, and (d) maintaining contraceptive efficacy. While contraceptive efficacy is equivalent between the two formulations, studies among adult women demonstrate equivalent adverse event profiles [4], including time to ovulation after drug cessation [5]. Studies of adult women have demonstrated interest in and feasibility of self-administration of DMPA-SC [6], but this issue has not been addressed among younger women.

We conducted this study of DMPA use among adolescent women to assess adolescent women’s (1) interest in self-administration of DMPA-SC, (2) proficiency in self-administering DMPA-SC, and (3) perceived supports needed for home-based self-administration of DMPA-SC.

2. Materials and methods

Data for this descriptive analysis exploring DMPA-SC self-administration were drawn from a study designed to compare DMPA-SC and DMPA-IM with respect to injection pain and likelihood of DMPA continuation among 55 adolescent women (unpublished, data available from first author). The larger study used a two-treatment, randomized cross-over design with a primary outcome of self-reported injection pain.

Eligible study participants were English-speaking adolescent females 14–21 years of age who were initiating or restarting therapy with DMPA as part of a routine health care visit in Midwest, urban, primary care adolescent medicine clinics. Participants were eligible regardless of medical indication for DMPA or prior history of sexual activity, as hormonal contraceptive methods are also used in anticipation of future sexual activity and for other reasons including menstrual irregularities.

Participants were excluded from the study if they had received DMPA within 6 months prior to enrollment, if they were unable to complete self-administered written English surveys due to linguistic or intellectual barriers, if they did not have telephone access for scheduled follow-up interviews, or if they had contraindications to DMPA use. Participants were also excluded if they received regular intramuscular or subcutaneous administration of other medications (e.g., insulin), or if they were receiving an injected medication at the time of DMPA administration (e.g., ceftriaxone). All participants provided informed consent, and parental permission was obtained for participants less than 18 years of age.

Prior to initiating study recruitment, computer generated 4-person blocked randomization determined injection sequence for 55 study participants. Injection sequence was either DMPA-SC for visit 1 and DMPA-IM for Visit 2, or DMPA-IM for Visit 1 and DMPA-SC for Visit 2. Opaque sealed envelopes, one per participant, were sequentially numbered and contained a page indicating the randomized injection sequence. After informed consent was obtained at Visit 1 (time 0), the participant was assigned the next sequential numbered envelope and was given the injection formulation indicated for Visit 1. At Visit 2 (time 12 weeks), they received the alternate DMPA injection. At Visit 3 (time 24 weeks), participants chose which DMPA formulation to receive as an outcome measure of formulation preference. All Visit 1, 2, and 3 injections were administered by study personnel who were trained in standard injection techniques for both DMPA formulations. DMPA-IM 150 mg was administered in the gluteal muscle (participant chose right or left side) using a 23-gauge × 1-inch needle. DMPA-SC 104 mg was administered in the anterior abdominal wall (participant again chose right or left side). The injection is available in a 0.65mL, single dose, pre-filled syringe. It is pre-assembled with an UltraSafe Passive™ Needle Guard device, and packaged with a 26-gauge × 3/8 inch needle to be used for injection [3].

Prior to each injection, participants completed written English surveys. The survey measure used in the current analysis was an 11-point Likert item rating desire to receive DMPA outside of the clinic setting (“I would like the Depo shot better if I didn’t have to come to clinic to get it”; 0 = not true, 10 = very true), and was completed by all participants presenting for the visit, even if discontinuing DMPA.

At the completion of Visit 3, semi-structured interviews exploring use of DMPA in general, experiences with each formulation, and reasons for choosing DMPA-IM or DMPA-SC were conducted by research personnel. All participants presenting for the visit were interviewed, regardless of DMPA formulation or discontinuation. Interest in self-administration of DMPA-SC at home was further explored with the question “Would you like DMPA-SC better if you could give your shot at home when you could not make it to your clinic appointment?” Participants were then asked if they were interested in learning self-administration of DMPA-SC. Interested participants returned for Visit 4 (time 36 weeks).

At Visit 4, participants again completed a pre-injection survey. Self-administration of DMPA-SC was then taught and observed. Using enlargements of the written and illustrated injection instructions from the DMPA-SC package insert, and using a sample of the injection device to demonstrate, a research assistant individually educated each participant on the following 5 steps of self-administration: (1) Choosing correct injection site, (2) Cleaning injection site, (3) Assembling injection device, (4) Self-injecting DMPA-SC, and (5) Disposing of the injection device. For each of these 5 steps of self-administration, trained observers rated participant Proficiency as: independent [I], independent with reassurance before proceeding [R], with continuous verbal instruction [V], or nurse performed this step [RN]. Trained observers also rated participants’ overall proficiency self-administering DMPA-SC as: independent, after repeat education, with assistance, or not competent to self-administer.

Visit 4 concluded after participants completed a semi-structured interview focusing on the experience of DMPA-SC self-administration and exploring self-administration at home with the question “If the shot were available at your pharmacy, would you want to give it to yourself at home?” Responses (no/yes) were elaborated upon with follow-up questions about benefits and barriers to home DMPA-SC use. The Visit 4 interview also assessed supports needed for home self-administration via the open-ended question “What things would make it easier for you to give the shot to yourself at home?” If no response was given, participants were prompted by the interviewer with “for example, things like a reminder when the shot is due, or nurse assistance by phone.”

Baseline characteristics were compared between four subgroups of participants – those choosing to learn self-administration, those choosing not to learn self-administration, those who discontinued DMPA, and those lost to follow-up. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous outcomes and Pearson’s chi-square analysis was used for categorical outcomes. All data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0, and differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

Descriptive statistics assessed interest in receiving DMPA outside of the clinic setting (mean/SD), number of participants interested in self-administration, understanding of initial injection education (y/n), requested immediate repeat injection education (y/n), and number of participants at each level of Proficiency for each step of self-administration and for overall proficiency self-administering. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University/Purdue University at Indianapolis and Clarian Health Partners.

3. Results

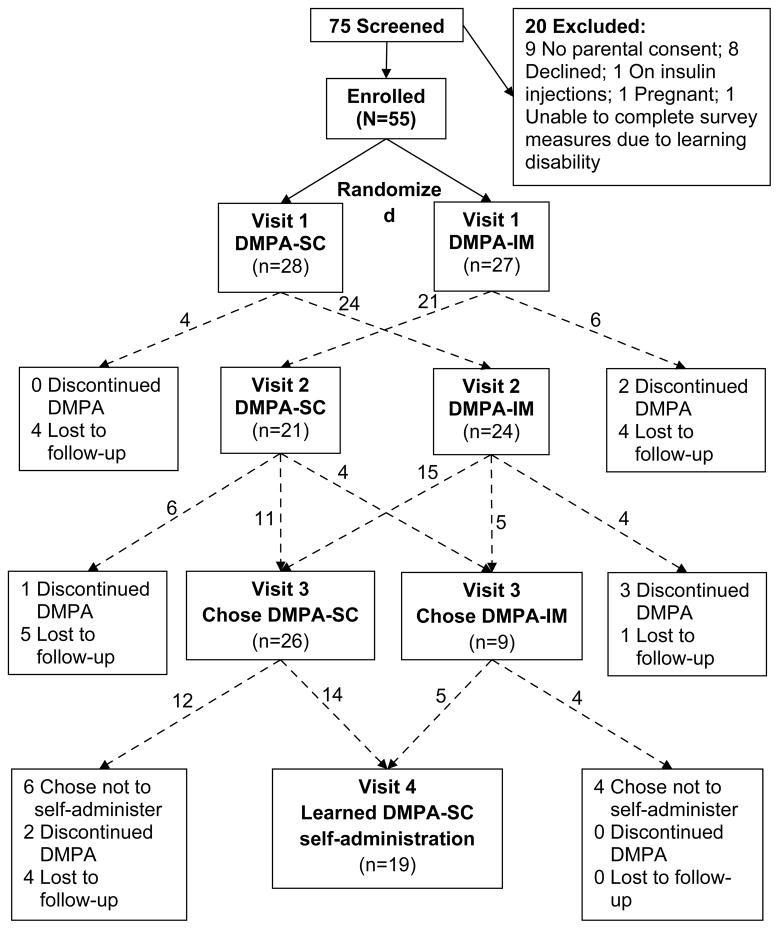

Sample recruitment, and patient flow and retention throughout the study protocol are depicted in Fig. 1. Fifty-five study participants were enrolled. Baseline sample characteristics for the entire sample, and comparisons between the four subgroups (chose to learn self-administration, chose not to learn self-administration, discontinued DMPA, and lost to follow-up), are shown in Table 1. Reflecting the patient population of the clinics from which participants were recruited, the sample was predominately African American. One fifth (11/55) of participants reported having never had sexual intercourse, and 4 reported a previous pregnancy. Young women who chose to self-administer DMPA-SC had fewer years of menstruation than those who discontinued DMPA (mean 4.1 vs. 6.3 years, p=0.023) and those lost to follow-up (mean 4.1 vs. 5.3 years, p=0.041). All other baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between subgroups.

Fig. 1.

Participant recruitment, flow, and retention.

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics at enrollment

| Total sample (N=55) | Chose DMPA-SC self- administrat ion (N=19) | Chose not to self- administer DMPA-SC (N=10) | Discontinued DMPA (N=8) | Lost to follow-up (N=18) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

|

Race % (n)*

| ||||||

| African American | 83.6 (46) | 89.5 (17) | 70.0 (7) | 62.5 (5) | 94.4 (17) | 0.174 |

| White | 9.1 (5) | 5.3 (1) | 30.0 (3) | 12.5 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic | 1.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.6 (1) | |

| Other/missing | 5.5 (3) | 5.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 25.0 (2) | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Age in years mean (SD)

| ||||||

| 16.5 (1.6) | 16.3 (1.6) | 15.8 (0.6) | 17.2 (2.1) | 16.9 (1.6) | 0.141 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Highest educational grade level mean (SD)

| ||||||

| 9.2 (1.8) | 8.9 (2.0) | 8.5 (1.0) | 10.3 (1.7) | 9.4 (1.8) | 0.164 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Highest maternal education % (n)*

| ||||||

| Some HS | 47.3 (26) | 36.8 (7) | 30.0 (3) | 62.5 (5) | 61.1 (11) | 0.610 |

| HS Graduate | 30.9 (17) | 26.3 (5) | 50.0 (5) | 37.5 (3) | 22.2 (4) | |

| GED | 5.5 (3) | 5.3 (1) | 10.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 5.6 (1) | |

| Some College | 7.3 (4) | 15.8 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.6 (1) | |

| College Grad | 9.1 (5) | 15.8 (3) | 10.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 5.6 (1) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Age in years at menarche mean (SD)

| ||||||

| 11.8 (1.5) | 12.1 (1.6) | 12.0 (1.5) | 11.1 (1.3) | 11.6 (1.5) | 0.497 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Years menstruating mean (SD)

| ||||||

| 4.7 (2.1) | 4.1 (1.3)ab | 3.7 (1.8) | 6.3 (3.2)a | 5.3 (1.9)b | 0.026 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Have never had sex % (n)

| ||||||

| 20.0 (11) | 10.5 (2) | 40.0 (4) | 25.0 (2) | 16.7 (3) | 0.296 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Previous Pregnancy % (n)

| ||||||

| 7.3 (4) | (1) | 0 | (2) | (1) | 0.164 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Prior use of hormonal contraceptive methods % (n)

| ||||||

| No prior method | 41.8 (23) | 26.3 (5) | 70.0 (7) | 37.5 (3) | 44.4 (8) | 0.091 |

| DMPA | 25.5 (14) | 31.6 (6) | 10.0 (1) | 12.5 (1) | 33.3 (6) | |

| COC | 32.7 (18) | 36.8 (7) | 20.0 (2) | 37.5 (3) | 33.3 (6) | |

| Patch | 20.0 (11) | 15.8 (3) | 20.0 (2) | 50.0 (4) | 11.1 (2) | |

| Ring | 1.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12.5 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| >1 prior method | 14.5 (8) | 10.5 (2) | 10.0 (1) | 37.5 (3) | 11.1 (2) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Condom at first sex % (n)

| ||||||

| 65.5 (36) | 78.9 (15) | 40.0 (4) | 62.5 (5) | 66.7 (12) | 0.389 | |

|

| ||||||

|

Condom at last sex % (n)

| ||||||

| 56.4 (31) | 73.7 (14) | 30.0 (3) | 50.0 (4) | 55.6 (10) | 0.437 | |

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous outcomes and Pearson’s chi-square analysis was used for categorical outcomes

Added percentages range from 100.0–100.1 due to rounding of decimals.

Values which share a superscript differ from one another at p<0.05 in difference in means t-test.

On the survey measure “I would like the shot better if I didn’t have to come to clinic to get it,” the 11-point Likert ratings clustered around 0, 5 and 10, and were therefore coded as low (0–2), medium (3–7), and high (8–10) interest in receiving DMPA outside of the clinic setting. Data by visit are summarized in Table 2. At any given visit, there were no differences in interest based on method of DMPA administration (SC or IM, data not shown.) In subgroup comparisons, participants who chose to learn self-administration had higher interest in receiving DMPA outside of the clinic setting than those who chose not to learn (mean 5.1 vs. 1.5; p<0.05) and this trend was present at Visit 2 (mean 3.6 vs. 1.3; p<0.1). No other differences in interest were noted between the four subgroups.

Table 2.

Interest in receiving DMPA outside of the clinic setting by visit

| Clinic Visit | Low interest* % (n) | Medium interest* % (n) | High interest* % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 (N=55) | 56 (31) | 22 (12) | 22 (12) |

| Visit 2 (N=47) | 60 (28) | 28 (13) | 13 (6) |

| Visit 3 (N=39) | 56 (22) | 15 (6) | 28 (11) |

| Visit 4 (N=22) | 41 (9) | 32 (7) | 27 (6) |

11-point Likert ratings for agreement with the statement “I would like the shot better if I didn’t have to come to clinic to get it,” were coded as Low (0–2), Medium (3–7), and High (8–10).

In interviews, of the 39 participants completing Visit 3, 16 (41%) stated that they would like DMPA-SC better if they could give their shot at home when they could not make it to their clinic appointment. The remaining 23 participants cited that they were not confident in their ability to give the injection properly, feared needles, or felt that shots fell under the domain of the clinic and should not be done at home. Some of these participants stated that if they were more comfortable with the needle, were supervised by an adult, or had an adult give them the shot then DMPA-SC at home would be acceptable.

Of the 35 participants who continued DMPA at Visit 3, 26 (74%) opted to learn DMPA-SC self-administration. Twenty-two participants presented for Visit 4. At the completion of Visit 4, 16 of 22 participants (29% of the total 55 participant sample) stated that they would self-administer DMPA-SC at home if it were available at their local pharmacy. Of these 16, six had previously stated at Visit 3 that they would not be interested in self-administration at home. Six of 22 participants at Visit 4 would not do home self-administration of DMPA-SC, but cited that nursing support by phone, mother giving injection, or being “older” and more confident self-injecting would make self-administration acceptable.

Of the 22 participants who presented for Visit 4, 2 discontinued DMPA and one choose not to self-administer at the time of the visit, leaving 19 who completed self-administration. Ninety-five percent (18/19) of participants learning DMPA-SC self-administration expressed verbal understanding of injection technique after initial education; 24% requested immediate repeat education prior to injecting. Percentages of participants rated at each level of Proficiency for the 5-steps of self-administration, and at each level for overall proficiency self-administering DMPA-SC are shown in Table 3. Eighty four percent (16/19) of participants chose the correct injection site and nearly 90% (17/19) cleaned the correct injection site independently or with verbal reassurance before proceeding. The majority assembled the injection device (84%, 16/19) and self-injected DMPA-SC (68%, 13/19) independently or with verbal reassurance. For most participants (11/19), the RN disposed of the injection device after the study participant forgot the disposal step and left the device on the counter in the exam room. Proficiency level for overall ability to self-administer DMPA-SC was: 42.1% (8/19) independent, 21.1% (4/19) independent after repeat education, 21.1% (4/19) with assistance, and 15.8% (3/19) not competent to self-administer.

Table 3.

Proficiency self-administering DMPA (N=19)

| Independent % (n) | Reassurance % (n) | Verbal instruction % (n) | RN performed % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Chose correct injection site | 78.9 (15) | 5.3 (1) | 5.3 (1) | 10.5 (2) |

| Step 2: Cleaned injection site | 89.5 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10.5 (2) |

| Step 3: Assembled injection device | 47.4 (9) | 36.8 (7) | 15.8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Step 4: Self-injected | 31.6 (6) | 36.8 (7) | 15.8 (3) | 15.8 (3) |

| Step 5: Disposed of injection device* | 21.1 (4) | 21.1 (4) | 0 (0) | 57.9 (11) |

| Independent % (n) | Re-education % (n) | Assistance % (n) | Not competent % (n) | |

| Overall proficiency* | 42.1 (8) | 21.1 (4) | 21.1 (4) | 15.8 (3) |

Added percentages total 100.1 due to rounding of decimals.

After learning self-administration in the clinical setting, participants were asked open-ended questions about benefits and barriers to home-based self-administration. Benefits were decreased time waiting in clinic, decreased transportation time and costs, and not having to miss other activities (e.g., work and school) in order to receive DMPA. Barriers identified were difficulty remembering when the next DMPA dose should be given, and concerns about administering the injection properly. To enable self-administration at home, participants identified need for reminder of timing of next dose, written/illustrated instructions, another trained injector (mom) at home, and on-call technical assistance.

4. Discussion

Our data demonstrate that many adolescent women are interested in DMPA availability outside of the clinical setting, and are able to self-administer DMPA-SC after brief education. In practice, self-administration of injected medications is common. Adult patients routinely self-administer subcutaneous insulin for diabetes and enoxaparin for venous thromboses after brief outpatient education. Self-administration of injected medications by adolescents is not well described in literature. In pediatrics, medication injections are commonly administered by a caregiver, though patients often participate. One case series of patients receiving subcutaneous interferon was conducted after a young girl requested self-injection. Of the 11 children aged 8–16 years who desired self-injection, all performed dose calculations, measured and administered their injections correctly [7]. Our data confirm that adolescents are interested in self-injection of medications and that most are competent to administer their first self-injection correctly. Children and adolescents with diabetes perform dose calculations and self-administration of insulin, particularly as they spend more time with peers rather than under direct caregiver supervision. Unlike self-injection of insulin, which is practiced multiple times daily, DMPA-SC injection occurs every three months, and patients may not remember less frequently practiced correct technique. However, DMPA-SC is a fixed-dose pre-filled injection device, which greatly simplifies self-administration.

Contraceptive self-injection has not been widely investigated. Though no data on self-administration of DMPA-SC by adult women has been published, a study was conducted of intramuscular self-injection of a combined monthly contraceptive containing medroxyprogesterone acetate 25 mg and estradiol cyprionate 5 mg. The 10 study participants had high contraceptive method satisfaction and compliance with the dosing regimen. All subjects preferred home self-administration, and 9 of the10 would recommend home self-injection to other women. They also had decreased contraceptive associated costs for transportation to clinic, child-care, and missed work [8]. Potential avoidance of these costs was articulated by our adolescent study sample as benefits to home self-administration of DMPA-SC.

Home-based options for managing other aspects of reproductive health have had rapid uptake and high satisfaction among both men and women. Just as home-based vaginal swab and urine sample collections have increased screening for sexually transmitted infections [9,10], home-based DMPA-SC could increase DMPA use. This potential for increased DMPA use was demonstrated in a cross-sectional survey of adult women attending a family planning clinic. Among 176 current DMPA-IM users, 67% wanted to self-administer DMPA-SC, which is consistent with our finding that 74% of adolescent women chose to learn self-administration. Of the 275 DMPA non-users in the adult survey, 11% did not choose DMPA due to the required office visits, but 26% would seriously consider DMPA-SC if they could self-administer at home. Forty-eight women were surveyed who had previously used, but discontinued DMPA. Though only 10% reported DMPA discontinuation due to the required office visits, 40% would be interested in resuming DMPA if they could self-administer at home [6]. We demonstrate that adolescent women also have interest in home self-administration of DMPA-SC. As a population disproportionally affected by both barriers to contraceptive access and high rates of unintended pregnancy, adolescents warrant additional focus as a unique population which could benefit substantially from home DMPA-SC.

It is important to acknowledge that clinic visits which are scheduled for DMPA dosing include provision of other health care services. These may include discussion of experienced and expected contraceptive side effects, screening for sexually transmitted infections, and general health promotion and disease prevention. Clinical interactions also provide important opportunities for strengthening the therapeutic relationship between patient and provider, and could positively influence patient satisfaction with and adherence to DMPA. However, data suggest that patient satisfaction and adherence are not adversely impacted by administration of DMPA-SC outside of the traditional clinic setting. In a cross-over trial in which each participant received three injections of DMPA-SC in clinic and three injections at a pharmacy, adult women had equal satisfaction with and continuation of DMPA-SC in both venues [11].

Recommended provision of important health care services does not differ based on contraceptive method. Users of oral contraceptive pills, transdermal contraceptive patches, and intravaginal contraceptive rings have contraceptive access which is not dependent on strict attendance to clinic appointments. For users of these methods, if a visit is missed, it can be rescheduled at any date, and contraceptive refills can be provided by phone to the woman’s pharmacy. This disparity in contraceptive access for DMPA users is inherent to in-clinic administration of DMPA, and could be reduced through home-based self-administration for selected patients.

Allowing DMPA use outside of the clinic setting will improve access to this highly effective, safe, long-acting reversible contraceptive, and may increase its use, thereby decreasing unintended pregnancy. Continued inclusion of adolescent women in this line of research, and addressing their unique developmental needs and minor status, will be essential to significantly impact the high unintended pregnancy rates in the Unites States. Our demonstration of interest in and ability to self-administer DMPA-SC in a small, homogenous group of adolescent women is insufficient justification for offering home-based DMPA-SC to all patients. However, this study is the first assessment of interest and proficiency in self-administration of injected contraception among adolescent women, and of DMPA-SC self-administration in any age group – a necessary first step towards making home self-administration a feasible option.

Home-based DMPA-SC use will require systems for maintaining communication with the prescribing clinician, providing on-call technical support for patients, and reminding patients when subsequent DMPA doses are due. Prior to implementing this novel approach to DMPA-SC use in clinical practice, it will be essential to assess knowledge retention of injection method, and need for re-education prior to subsequent injections. Our data provide the foundation for development of the systems needed to make home-based self-administration of DMPA-SC a standard contraceptive option for women of all ages.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: HRSA/T71 MC00008, NIH/NCRR RR025761

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Martinez G, Copen CE, Abma JC. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2011;23(31) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2004;23(24) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depo-SubQ Provera 104 [package insert] Pharmacia and Upjohn Co Division of Pfizer Inc; New York, NY: Oct, 2007. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/021583lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain J, Jakimiuk AJ, Bode FR, Ross D, Kaunitz AM. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of DMPA-SC. Contraception. 2004;70:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain J, Dutton C, Nicosia A, Wajszczuk C, Bode FR, Mishell DR. Pharmacokinetics, ovulation suppression and return to ovulation following a lower dose subcutaneous formulation of Depo-Provera. Contraception. 2004;70:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakha F, Henderson C, Glasier A. The acceptability of self-administration of subcutaneous Depo-Provera. Contraception. 2005;72:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott MJ. “I want to do it myself!” Interferon self-injection for children with chronic viral hepatitis. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2005;28:406–9. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanwood NL, Eastwood K, Carletta A. Self-injection of monthly combined hormonal contraceptive. Contraception. 2006;73:53–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaydos CA, Dwyer K, Barnes M, et al. Internet-based screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to reach non-clinic populations with mailed self-administered vaginal swabs. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:451–7. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000200497.14326.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaydos CA, Barnes M, Aumakhan B, et al. Can e-technology through the Internet be used as a new tool to address the Chlamydia trachomatis epidemic by home sampling and vaginal swabs? Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:577–80. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a7482f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picardo C, Ferreri S. Pharmacist-administered subcutaneous depot medorxyprogesterone acetate: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2010;82:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]