Abstract

Background

Postnatal unit rooming-in promotes breastfeeding. Previous research indicates that side-cars (three-sided bassinets that lock onto the maternal bed-frame) faciliate breastfeeding after vaginal birth more than stand-alone bassinets (standard rooming-in). No study has previously investigated side-car bassinet use after cesarean, despite the constraints on maternal-infant interactions that are inherent in recovery from this birth mode.

Objective

To test the effect of the side-car bassinet on postnatal unit breastfeeding frequency and other maternal-infant behaviors compared to a stand-alone bassinet following cesarean birth.

Methods

Participants were recruited and prenatally randomized to receive the side-car or stand-alone bassinet for their postnatal unit stay between January 2007 and March 2009 in Northeast England. Mother-infant interactions were filmed over the second postpartum night. Participants completed face-to-face interviews before and after filming. The main outcome measures were infant location, bassinet acceptability, and breastfeeding frequency. Other outcomes assessed were breastfeeding effort, maternal-infant contact, sleep states, midwife presence, and infant risk.

Results

Differences in breastfeeding frequency, maternal-infant sleep overlap, and midwife presence were not statistically significant. The 20 dyads allocated to side-car bassinets breastfed a median of 0.6 bouts/ hour compared to 0.4 bouts/hour for the 15 stand-alone bassinet dyads. Participants expressed overwhelming preference for the side-car bassinets. Bedsharing was equivalent between the groups, although the motivation for this practice may have differed. Infant handling was compromised with stand-alone bassinet use, including infants positioned on pillows while bedsharing with their sleeping mothers.

Conclusions

Women preferred the side-car but differences in breastfeeding frequency were not significant. More infant risks were observed with stand-alone bassinet use.

Background

Cesarean birth presents a practical barrier to breastfeeding due to limited maternal mobility and persistent postpartum maternal pain.1–3 Despite the high incidence of cesarean,4–6 little is known about how hospital practices contribute to or compound the adverse effects of this childbirth context on the establishment of breastfeeding. Recent guidance from the United Kindgom7 states that women should be offered additional support initiating breastfeeding after cesarean birth, but also that women are not at increased risk of difficulties once breastfeeding is established. Initial maternal interactions with newborns have been rated less favorably following cesarean than after vaginal birth, which was related to the longer elapsed time between birth and first holding the infant.8 Rowe-Murray and Fisher also found that elevated maternal emotional distress post-cesarean persisted at eight months postpartum. Better understanding of interactions among mothers, infants, and their environments may explain the lower rates of breastfeeding documented after cesarean birth9–11 and the specific vulnerabilities facing these dyads.

Mothers balance their time and energy between infant care and their own needs, such as sleep,12 and recovery from cesarean diverts effort from breastfeeding.13 Sucessful lactation requires frequent suckling during the day and night. For the mother, this entails awareness of infant cues and the ability to respond. An optimal start on the postnatal unit is challenging, however, with low levels of midwifery staffing coupled with complex maternity needs.14 This issue may be especially relevant for the diverse population of women who experience cesarean childbirth because they require frequent assistance with maneuvering themselves and accessing infants. Although a longer inpatient stay may be beneficial,15 this is not often physically or economically feasible. Alternatively, postnatal care might be modified to better address the needs of the cesarean population.

One intervention to support families after cesarean birth involves promoting maternal-infant proximity.16 Continuous rooming-in is one of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding17 because it allows mothers to hear infant cues and facilitates interaction. However, locating infants in stand-alone bassinets may not provide sufficient opportunity for extended skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding, especially during cesarean recovery. Side-cars (three-sided bassinets that lock onto the maternal bed-frame) are in mothers’ line of vision and do not require women to exit the bed to access their newborns. Although hospital side-cars are not a new concept,18 we are unaware of widespread use for any population.

Postnatal unit arrangements are crucial in maternal-infant interactions when considered within the developmental science framework. This systems-perspective emphasizes bidirectionality,19 with infant cues and maternal responses shaping each other. Consistent with this conceptualization are the findings that bedsharing promotes breastfeeding20 and that infant sleep locations affect postnatal unit breastfeeding frequency after vaginal birth.21 In both of these studies, infants randomized to sleep in close proximity to the mother (laboratory bedsharing versus sleep in separate rooms or postnatal unit bedsharing versus rooming-in with a side-car or a stand-alone bassinet) breastfed significantly more frequently during the observation periods. The results suggest that some breastfeeding challenges encountered in hospitals are an iatrogenic consequence of the physical separation of mothers and infants imposed by night-time arrangements.22

In previous research on postnatal unit rooming-in,21 cesarean birth was an exclusion criterion. The present study builds on that work. In this article, we describe the impact of randomly allocated side-car or stand-alone bassinets on breastfeeding sessions and maternal-infant interactions after non-labor cesarean.

Objectives

We hypothesised that side-car bassinets would be associated with more frequent breastfeeding compared to stand-alone bassinets. Infant location and risk were measured because data regarding hospital infant falls and other handling issues are sparse,23–24 and use of the two bassinet types have not been investigated after cesarean. Night-time infant locations can introduce various risks, so direct observations are crucial to understanding these practices. Additional outcome measures for the present study were bassinet acceptability, breastfeeding effort, maternal-infant contact, sleep states, and midwife presence in participants’ rooms over the observation period to ascertain how the intervention affected postnatal unit dynamics.

Methods

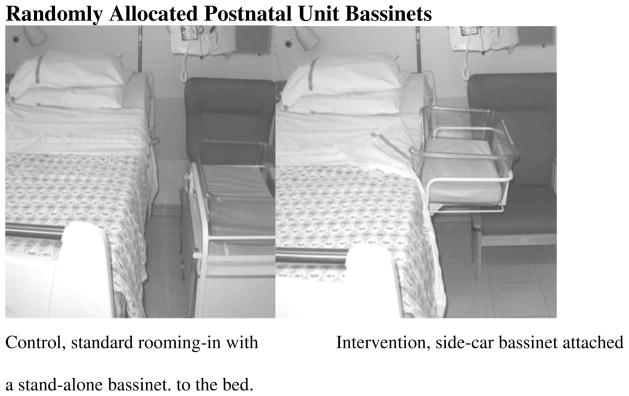

A randomized trial with a parallel deisgn was used to compare the interactions of mother-infant dyads prenatally allocated to receive a postnatal unit side-car or stand-alone bassinet during cesarean recovery (Figure 1). The side-car bassinet has two latches that fit over the side frame of the maternal bed. A flat clamp positioned underneath the mattress locks the side-car in place. The stand-alone bassinet comprises a clear acrylic bassinet in a frame on a four-wheeled cart.

Figure 1.

Randomly Allocated Postnatal Unit Bassinets

Setting

This study was conducted at a tertiary-level hospital in Northeast England with approximately 5,400 births annually. The maternity unit had a Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) certificate of commitment, but was not BFHI accredited. The cesarean rate at the hospital was 22%, compared with a national rate of 34% in England.25

At the study hospital, continuous rooming-in is standard on the postpartum unit for all healthy dyads. Infant feeding support is provided by midwives as a part of routine care. Following cesarean, women are bedbound until the day after childbirth when catheters are removed. Mothers signal for midwifery assistance by pushing a call button. The required nighttime staffing level on the unit is 3 midwives and 1 health care assistant for the 24 beds. The average stay after cesarean birth on this ward is 2 or 3 days.

Participants

Participants were non-smoking mothers of healthy singletons who initiated breastfeeding, experienced term cesarean without labor, and spent the second postpartum night at the delivery hospital in a single or double room. A sample of 72 would be necessary to detect a group difference in breastfeeding frequency, based on a two-sided sample size calculation with a sigma 1.5 (estimated based on 21), significance level of 0.05, and 80% power.

Procedures

Ethical and institutional approval was obtained from Durham University and the Newcastle and North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee 1. Recruitment occurred January 2007 to December 2007 and October 2008 to March 2009. Potential participants were approached at surgical booking appointments occuring at 36 weeks gestation or through a postal mailing. The postal mailing was adopted for the second recruitment period because of the initiation of other research on the study ward in January 2008.26 The study was overlapping in inclusion criteria and prenatal random allocation of the bassinet types, but it did not involve filming. The timing, design, and participants for the other study permitted collaboration to obtain a targeted sub-sample of appropriate dyads for this project.

The inclusion criteria specified that a mother be pregnant with a single infant, expecting to deliver after at least 37 weeks gestation, non-smokers during pregnancy, at least 18 years of age, scheduled for cesarean at the study hospital, and considering breastfeeding. The additional criterion of planning to spend the entire postnatal stay at the study hospital was added after it emerged that some women transfer to smaller hospitals more local to their homes after the first postpartum night. Exclusion criteria included women whose midwives advised against participation. This occurred once due to a woman being HIV-positive.

Enrollment entailed return of completed consent forms prior to childbirth and assignment of an anonymous study number. The second author, who was not involved in recruitment, used a random number table to allocate bassinet types. The allocation was communicated to the participants by telephone and to the midwifery manager by e-mail. The manager alerted midwives as to which women were trial participants and for whom they should provide the sidecar. The allocated bassinet was available for the participants’ entire postnatal unit stay. The study was described as an investigation of night-time mother-infant interactions without mention of the specific outcome measures.

Factors that rendered a participant ineligible after enrollment were not meeting one or more of the inclusion criteria, mother or infant being unwell, or the dyad not having a scheduled caesarean due to the spontaneous onset of labor. The day after childbirth, each participant completed a semi-structured face-to-face interview with the first author, who then set-up a small camcorder and long-play videocassette recorder (VCR). The camcorder’s ‘night-shot’ facility permitted filming in complete darkness, and was mounted on a monopod clamped to the foot of the maternal bed. The VCR was housed in an attaché case positioned under the bed. Participants used the remote control to start recording once they were ready to sleep and were requested to let the equipment record continuously for the duration of the tape. Mothers and their midwives could stop the recording at any point. Participants were encouraged to care for their infants as usual and disregard the camera. No instructions were provided regarding bassinet use. Following filming, the video equipment was dismantled and mothers completed a brief follow-up interview. Participants were offered a copy of their videotape prior to giving final consent for it to be used in the study. A small gratuity was offered in the form of gift cards. Daytime behavior was not filmed due to the variable presence of visitors and their interactions with the mother-infant dyad. Hospital policy excluded visitors (including infant’s father) overnight.

Measures

Coded video observations were used to assess breastfeeding, infant location, maternal and infant sleep states, physical contact, midwifery presence in participants’ rooms, and infant risk between the trial arms. Semi-structured interviews documented maternal experiences with infant care and bassinet use. Questions included “do you think anything has impacted your ability to interact with your baby?”

Observational Methods

Filming permitted objective comparison of the effects of the bassinet types on maternal-infant interactions. A taxonomy was used with Noldus: The Observer 5.0 to categorize behavioral states of mothers, infants, and the presence of midwives. This method derives from naturalistic observation of animals27 and was based on previous taxonomies.20–21 The main outcome measure, breastfeeding sessions, was defined as separate bouts of suckling at the breast with at least 5 minutes between the ending and onset of the infant’s mouth on the breast. This definition therefore included nutritive and nonnutritive suckling. Breastfeeding effort comprised the behaviors of infants being put to the breast (maternal feeding attempts) plus breastfeeding sessions. The full list of study codes and definitions used in this analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Observational Codes and Definitions

| Codes | Categories and Definitions | Modifiers and Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding session | The infant’s mouth is over the nipple on the breast until the removal of the infant’s moth from the breast. A new breastfeeding session is defined by at least 5 minutes separating the removal of the infant’s mouth from the breast and onset of the infant’s mouth on the breast. |

None. |

| Total breastfeeding effort | The combination of breastfeeding sessions and breastfeeding attempts. Breastfeeding attempts: infant’s mouth is put to the breast, but no latching and/or suckling is observed. |

None. |

| Infant Location | Side-car: infant is located in the side-car bassinet. Stand-alone: infant is located in the standalone cot. Maternal bed: infant is located on the maternal bed. Other: infant is in the hospital room, but held by the mother, midwife, or other (not while sitting on the maternal bed). Out of room: the infant is located place other than the observed hospital room. |

Infant surface. Mattress: the infant is located in the side-car, stand-alone or maternal bed and the primary surface upon which the infant is positioned is on the mattress of that location. Mother: the infant is located in the maternal bed or on the mother while she is otherwise in the room and the primary surface upon which the infant is positioned is on the mother’s body. Pillow: the infant is located in the side-car, stand-alone, or maternal bed and he primary surface upon which the infant is positioned is on a pillow. |

| Infant Risk | Risk: infant appears to be in a situation that is hazardous, or potentially dangerous. No risk: infant does not appear to be in a situation that could cause immediate harm |

Type of risk. Position: the infant is asleep on his/her stomach on a surface other than the mother. Falling: the infant is in a precarious position in a location with no means of fall prevention. Suffocation: the infant’s airways are covered. Entrapment: the infant is wedged between two surfaces in a location. Overlaying: the infant is trapped under the mother. Other: the infant is in a different hazardous situation (specify).. |

| Mother-infant physical contact | In contact: mother and infant are in physical contact. This could be partial or whole body contact. Not in contact: mother and infant are not in physical contact. The infant could be within the mother’s arm reach, beyond mom’s arm reach in the same room, or in a different room. |

None. |

| Sleep status | Awake: eyes open and/or substantial movements. Asleep: eyes closed with limited movements, such as twitching. |

None. |

| Midwife present | In: midwife is visually located in the observation room and/or heard directly speaking to the participant. Out: midwife is not visually located in the observation room or heard directly speaking to the participant. |

None. |

All behaviors were continuously coded as states, which is a measure of frequency and duration. For all codes, indeterminate was recorded if the video was recording, but visual and audio data made the behavior indiscernible. For all codes, no data was recorded if the video was turned off.

The first author coded videotapes from maternal sleep onset to last waking (or to the tape end if still sleeping). Participants were classified as cross-overs from their allocated groups if infants spent 50% or more of their sleep time in an arrangement other than their allocated bassinet. Those assigned to the stand-alone bassinet group could not opt for the intervention condition (side-car bassinet). However, the side-car participants could revert to standard care (stand-alone bassinet) on request.

Interviews

The pre-filming interview focused on women’s childbirth experiences, infant caretaking plans, and postnatal interactions. The post-filming interview explored mothers’ night-time experiences and thoughts on the bassinet types. Interviews were semi-structured, open-ended, and conducted in private. Questions were worded in a non-leading manner, and probes were used to elicit full accounts. The interviewer recorded responses verbatim through detailed notes. Medical record reviews and participant-completed socio-demographic questionnaires permitted sample description.

Data Analysis

Observational data were analyzed by a modified intention-to-treat analysis, comprising all completers. Including all randomized participants in the analysis was not possible because outcomes were generated using video and interview data. Women who withdrew, did not breastfeed, or left the postnatal unit early did not contribute data.

The frequency and duration of behaviors were analyzed as proportions of the observation period, which ranged from 4 to 8 hours. Intra-observer reliability was assessed by recoding video segments. A Cohen’s Kappa of 0.86, (the proportion of agreement exceeding that expected by chance), surpassed the recommended 0.70 threshold.28 After checking the normality of data in SPSS v.18 with the Shapiro-Wilk test, group comparisons were conducted using the chi-square test for two independent samples, Fisher exact test, independent-samples t test, and the Mann-Whitney tests where appropriate. Medians, ranges, mean differences, and confidence intervals are provided to provide faciliate comparison with previous research.21

Participant responses were entered into a matrix format verbatim for ease of comparison. Initial codes were then used to create thematic categories across all participants.29 The authors identified codes through an iterative process. Codes derived from research questions, such as “is anything influencing the way you are looking after your baby” and from refinements of the core issues that emerged, such as ‘managing breastfeeding.’

Results

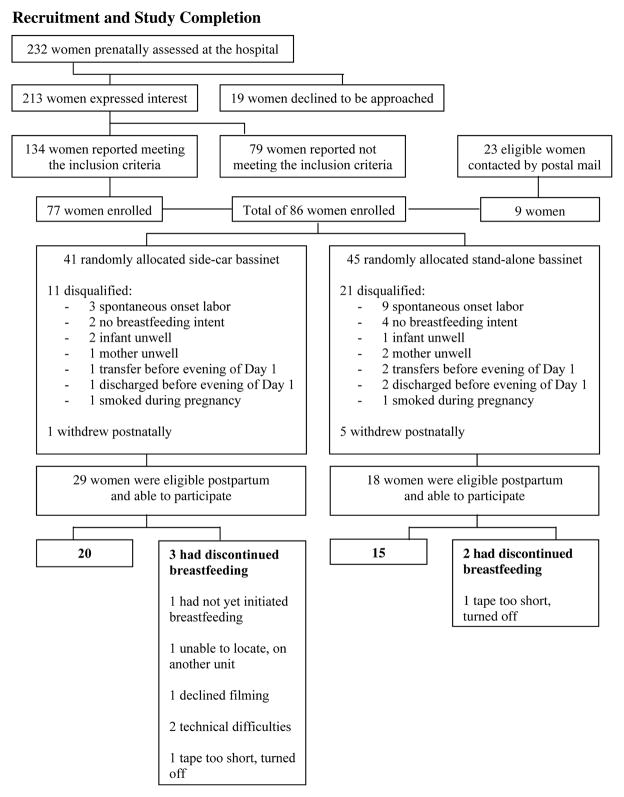

Seventy-seven of 134 (58%) eligible women approached face-to-face were enrolled together with 9 of 23 (39%) approached via postal recruitment. The overall enrollment rate to those eligible was 86/157=55%. Although 86 women were recruited, it was only possible to capture sufficient video observations for 35 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Recruitment and Study Completion

Participants were a mean age of 33.7 years (SD 4.9) and were mainly multiparous. Eighty-three percent were White British and 73% had a university degree. Over half of the infants were female, with a median gestational age of 39.1 weeks (range 38.4 to 41.1) and a mean birth weight of 3.6 kilograms (SD 0.5). The recorded characteristics did not vary statistically between the 20 side-car and 15 stand-alone bassinet participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant Demographics by Filmed Bassinet Groups

| Side-car bassinet n=200 | Stand-alone bassinet n=15 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Maternal age in years | 34 (4.7) | 35 (5.3) |

| Birth weight in kilograms | 3.6 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.6) |

| Median (range) | ||

| Gestational age in weeks |

n=17 39.4 (38.4 – 41.1) |

n=14 39.1 (38.9 – 40.0) |

| Apgar at 1 minute | 9 (8 – 9) | 9 (8 – 9) |

| Apgar at 5 minutes | 9 (9 – 10) | 9 (9 – 10) |

| Percent (n) | ||

| Primiparous | 20.0 (4) | 6.7 (1) |

| Previously had cesarean section childbirth | 65.0 (13) | 53.3 (8) |

| Study cesarean conducted for a current medical condition+ | 10.0 (2) | 6.7 (1) |

| Living with partner | 100 (20) | 93.3 (14) |

| Mother had an undergraduate degree |

n=19 73.7 (14) |

n=14 71.4 (10) |

| Mother White European | 85.0 (17) | 80.0 (12) |

| Mother Afro-Caribbean | 5.0 (1) | 6.7 (1) |

| Mother Asian | 10.0 (2) | 13.3 (2) |

| Previously breastfed for any duration | 80.0 (16) | 86.7 (13) |

| Previously breastfed for ≥ 6 weeks |

n=19 63.2 (12) |

80.0 (12) |

| Infant female | 60.0 (12) | 73.3 (11) |

A current medical condition was defined as a condition affecting the mother, fetus, or both during the study pregnancy. This included breech positioning but not ‘repeat’ cesarean section. Medical conditions included fibroids and placenta previa. Most participants ‘repeat’ cesarean section childbirth or scheduled the cesarean because of previous complications with vaginal childbirth.

Between group differences on continuous variables were calculated using the independent samples t test, except for Apgar at 1 minute, Apgar at 5 minutes, and gestational age due to nonnormal distribution. Between group differences on proportions were calculated using the chi-square test for two independent samples or the Fisher exact test.

Breastfeeding, Sleep, and Midwifery Presence

There was a trend for more frequent breastfeeding and total breastfeeding effort, more mother-infant sleep overlap, and less midwifery presence in the side-car group, but these were not statistically different compared to the stand-alone group (Table 3). The observation periods included formula supplementation in 7 of 35 cases (20%), which was split evenly between the two groups (4 of 20 side-car and 3 of 15 stand-alone bassinet participants). The proportion of time mothers and their infants spent in physical contact, infant sleep time, and maternal sleep time did not differ between groups.

Table 3.

Mother-Infant Behaviors on the Second Postpartum Night by Filmed Postnatal Unit Bassinet Groups

| Median (range) | Mean Difference | 95% CI | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side-car bassinet n=20 | Stand-alone bassinet n=15 | Side-car to Stand-alone bassinet | |||

| Frequency of per hour: | |||||

| - Breastfeeding sessions | 0.64 (0.12 – 1.61) | 0.40 (0.00 – 1.07) | 0.26 | −0.01 – 0.52 | 0.09 |

| - Total breastfeeding effort | 0.73 (0.12 – 1.64) | 0.40 (0.00 – 1.11) | 0.27 | −0.01 – 0.56 | 0.10 |

| Proportion per hour: | |||||

| - Maternal bed as the infant sleep location | 0.22 (0.00 – 0.85) | 0.19 (0.02– 0.97) | −0.01 | −0.23 – 0.21 | 0.79 |

| - Mother-infant in physical contact | 0.55 (0.12 – 0.96) | 0.39 (0.12 – 0.89) | 0.10 | −0.08 – 0.28 | 0.23 |

| - Infant awake | 0.40 (0.14 – 0.67) | 0.32 (0.08 – 0.82) | 0.00 | −0.11 – 0.11 | 1.00 |

| - Mother awake | 0.43 (0.20 – 0.87) | 0.48 (0.17 – 0.85) | −0.04 | −0.17 – 0.08 | 0.48 |

| - Sleep overlap | 0.70 (0.18 – 0.82) | 0.49 (0.15 – 0.78) | 0.10 | −0.02 – 0.23 | 0.06 |

| - Mother asleep, infant awake | 0.09 (0.00 – 0.24) | 0.09 (0.03 – 0.54) | −0.04 | −0.12 – 0.03 | 0.44 |

| - Infant asleep, mother awake | 0.23 (0.07 – 0.73) | 0.32 (0.07 – 0.58) | −0.04 | −0.16 – 0.08 | 0.53 |

| - Midwife present | 0.00 (0.00 – 0.08) | 0.02 (0.00 – 0.11) | −0.01 | −0.03 – 0.01 | 0.06 |

P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Bassinet Acceptability

Mothers expressed overwhelming enthusiasm for the side-car. Participants who received the stand-alone bassinet spontaneously offered that the intervention “would have made a huge difference.” Most women (29 of 35) reported that the bassinet types affected their interactions with their infants. No mother commented unfavorably on the side-car, while 11 of 15 (73%) stand-alone participants commented unfavorably about their allocated bassinet. Participants described the side-car bassinet as permitting visual and physical access to their infants, enabling emotional closeness, facilitating breastfeeding, and minimizing the need to request midwifery assistance. Participants described the stand-alone bassinet as “awkward” and “clumsy.” One mother in the stand-alone group commented, “Last night I had to hit the buzzer [for the midwife] to get my baby out. I felt like I was pestering them [the midwives], but that [feeling] is all from me. They’re busy, but they are here for you.”

Participants recommended that the side-car bassinet be universally offered on postnatal units. Some said that they would not have roomed-in for the entirety of the night without the side-car because it facilitated settling their infants. Additionally, women said that they would not have managed to breastfeed without the access provided by the side-car bassinet:

“The side-car is fantastic…really good to be honest. I’m very sore and if I had to sit up or stand up, I couldn’t have done it [breastfeed in the night].”

37-year-old White third-time mother

“Actually the side-car is really good. I can be a lot more responsive and quicker. I pick him up straight away [from the side-car] whereas it takes me a good few minutes to get up out of bed. My little girl [previous baby] had been left crying [on the postnatal unit with the stand-alone bassinet]. I found this a lot easier. I could put my hand on him when he niggled [exhibited small movements or vocalizations].”

35-year-old White second-time mother

The side-car permitted infant contact with minimal maternal repositioning that mothers must substantially undertake with the stand-alone bassinet after cesarean childbirth:

“The [stand-alone] bassinet wasn’t especially good after a cesarean section. It requires a lot of twisting and bending forward which we aren’t supposed to do. So, it’s not the best. That’s why the bassinet was empty at the end of the night. She was crying a lot so they [the midwives] had to take her.”

39-year old White second-time mother

“I would sleep for 10–15 minutes, then my baby cried and I had to stand up. This [stand-alone] bassinet was too hard to use so I brought her into bed. I can’t pick up her up very easily. The side-car would’ve been much easier for a woman like me who had a cesarean section to get the baby, give milk, and set the baby back. It bothered me having to ring midwives every half hour in the night.”

29-year-old Asian third-time mother

Infant Location

No participants allocated to the side-car switched to the stand-alone bassinet. About one third of both groups of mothers bedshared with their infants for the majority of the night (11 of 35 participants). Cross-over from the allocated bassinet to bedsharing occurred with 7 of 20 sidecar and 4 of 15 stand-alone bassinet participants.

Infant Safety

None of the 35 infants experienced an adverse event in the course of this study. All mothers attempted to access their infant while reaching from a reclining or sitting position on the bed. Maternal movement was universally slow and often accompanied by grimaces. The height and angle of the stand-alone bassinet relative to the mother introduced several potential risks to infants. Observed stand-alone bassinet risks involved lifting infants without support for their heads, tipping the bassinet while attempting to return an infant, dropping an infant into the bassinet, and prone infant sleep. The prone infant sleep position, defined as infants asleep on their stomachs on a mattress or pillow, was observed in 1 of 15 stand-alone and 2 of 20 side-car participants. When infants were in their mother’s bed, those who had been randomly allocated to the stand-alone bassinet spent more time positioned on a pillow (8 of 15, median proportion of observation time 0.03, range 0.00–0.88 of the night) compared to those who had the side-car (3 of 20, median 0.00, range 0.00–0.01) instead of being on the mattress or their mother’s body. The mean difference in the proportion pillow use between the stand-alone versus side-car groups was 0.20 (0.04–0.35, p=0.009, Mann-Whitney U Test). Infants bedsharing on a pillow specifically when their mother was asleep occurred only in the stand-alone group (6 of 15 participants). This arrangement was significantly more likely in the stand-alone group compared to those allocated a side-car bassinet (p=0.003, Fisher’s Exact Test).

Discussion

This study contributes to understanding of breastfeeding difficulty after cesarean birth. Overnight observation of mother-newborn interactions were triangulated with maternal interviews on the postnatal unit. Findings from this preliminary mixed methods research suggest postnatal unit bassinet types may affect breastfeeding frequency, postnatal unit staff workloads, and infant risk.

Maternal accounts of their experience indicated breastfeeding after cesarean childbirth is constrained by inability to easily access their newborns while rooming-in. The side-car provided maternal benefit through ‘easier,’ but not more frequent, breastfeeding. In economics terms, there could be a maternal ‘cost ceiling’ in the early post-cesarean period in which women breastfeed infrequently because the burden is too great. Considering the needs within breastfeeding dyads may be key in facilitating more holistic and effective support.12

Interplay between people and place is increasingly identified as a contributor to health outcomes.30 Current systems of postnatal care render many families and health care providers unsatisfied.31 Dykes32 argues that the infant and the breast are often compartmentalized in breastfeeding discussions instead of acknowledging the relational and physiological connectedness between mother and child. Although Declercq et al.9 suggest that early brestfeeding cessation is an area for “teachable moments” to increase women’s commitment, the overwhelming need in health services may be for interventions to better support women’s realization of their breastfeeding plans. Maternal preference for the side-car bassinet suggest mothers desired their postnatal unit environments to be more accomodating.

As there can be a demonstrable gap between what people do and what they say happened, direct observation is a crucial component for investigating human behavior.33–34 Participant recall is also limited, and so video-recording enabled an objective, quantifiable comparison of the effects of the bassinet types. Although participant awareness of being observed may have altered the mothers’ behavior in unmeasurable ways, the video equipment was equally visible in both arms of the study.

Filming on a postnatal unit provided a unique insight into the constraints experienced by mothers following cesarean childbirth, revealing how the combination of maternal mobility limitations and the stand-alone bassinet introduced unanticipated risks to infants in terms of suboptimal handling and pillow use. The ability to identify a hazardous situation was limited, however, by stationary filming equipment that provided a single vantage point. Lack of physiological measurements limited the accuracy of classifications such as sleep state and risk. However, the use of monitors could affect participant comfort and infant handling.

As reported in Figure 2, mothers halted video recording infrequently. This suggests that the filming was not much of a breastfeedig disruption. This is important as Morrison et al.35 found that mothers described “frequent, erratic, and lengthy” postnatal unit activity as hindering their rest and infant care. Both maternal accounts and video observation demonstrated that use of the stand-alone bassinet after non-labor cesarean did not facilitate having infants “within easy reach” of their mothers as specified in WHO recommendations.36 Our qualitative data suggest that post-cesarean infants are not easily accessible with stand-alone bassinets. This context may lead to increased risk of accidents and harm.

Although bedsharing for the majority of the observation period was a frequent practice in both groups of participants, it occurred differently. Infants from the stand-alone bassinet group slept for significantly longer on a pillow on their mother’s lap when in the maternal bed. The pillow use may reflect the mothers falling asleep uninentionally before returning the infant to the stand-alone bassinet. It is unsurprising that a mother might delay stand-alone bassinet use if this will cause her pain or wake the infant. Bedsharing on the postnatal unit in beds not designed for infants to share, with medicated mothers, could lead to infant falling or suffocation. The practice of positioning an infant on a pillow while bedsharing with sleeping mothers is particularly concerning, as Blair et al.37 found that this arrangement is associated with Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Our observations regarding infant safety suggest that the side-car bassinet was preferable due to various infant risks observed with stand-alone bassinet use (poor infant support, bassinet tipping, more newborns sleeping on pillows on mothers). Participants also expressed greater satisfaction with the side-car than the stand-alone bassinet.

The observational coding was also conducted on a micro-level for predefined specific behaviors with a sufficient degree of intra-rater reliability, so the possibility of coder bias was limited despite the visibility of the bassinet types. The authors conducted the qualitative coding from responses to non-leading interview questions, but utilization of research assistants blind to the study hypotheses would be ideal to minimize potential bias.

In previous research, the side-car was determined to be marginally preferable to the maternal bed as an infant sleep site on the postnatal unit after vaginal birth21 because infants experienced face-covering by bed-sheets for a greater proportion of the observation in the bedshare group compared to the side-car bassinet group. However, Ball et al. found that the infant who experienced the greatest airway-covering in that study, although allocated to the bed-share group, experienced the airway-coverings while swaddled in a stand-alone bassinet. Results of these trials therefore indicate that it is the ways in which infant sleeping arrangements are implemented, not the structures themselves, that convey risk. The type of bassinet that mothers have during rooming-in is one of many aspects of their perinatal environment that may be made more family and breastfeeding friendly.

Although the recruitment target was met and women were willing to participate in the trial, a substantial number of women were disqualified following enrollment due to spontaneous onset of labor or the realization that an inclusion criterion, such as breastfeeding intent, had not been accurately represented at enrollment (Figure 2). The results are therefore underpowered. However, the proportion of enrolled participants filmed in this study, 35 of 86 (40.7%), is similar to the percentage achieved in previous comparable research, 61 of 144 (42.4%) with Ball et al.21 Future observational research may benefit from including dyads experiencing labor before their cesarean and anticipating a high rate of disqualification. The strict adherence to specified inclusion/exclusion criteria in this study limits generalizability of the results but ensured internal consistency and thereby enabled a valid test of efficacy. The next step would be to test random allocation of the side-car with samples representative of the population/s for which the bassinet types are of interest.

A larger sample is particularly important because we observed infrequent breastfeeding compared to previous overnight observations of breastfeeding dyads, which had similar sample sizes. Ball et al.21 obtained data on 18 bedsharing, 23 side-car, and 20 standalone bassinet dyads while McKenna et al.20 had 20 routinely bedsharing and 15 routinely solitary sleeping mother-infant pairs. As reported in Table 3, non-labor cesarean dyads allocated to side-car bassinets breastfed a median of 0.6 bouts/ hour compared to 0.4 bouts/hour for the stand-alone bassinet group. After vaginal birth, 21 those allocated to the side-car breastfed a median of 1.3 bouts/hour compared to 0.5 bouts/hour with stand-alone bassinets (a bedsharing group breastfed a median of 1.2 bouts/hour). Although maternal opportunity to recognize infant cues and access the babies is a critical issue during the first postnatal nights, breastfeeding is likely further impeded by the effects of surgical birth on infant feeding capabilities.38

Earlier provision of side-car basinets, such as in the birthing suite, may promote mother-infant interactions in general and especially breastfeeding. Previous research39 found that a two-hour separation of mothers and newborns was associated with differences in maternal sensitivity, infant self-regulation, and dyadic interaction at one year postpartum. Another study found that hospital practices that support mother-infant contact, such as skin-to-skin care, are associated with greater breastfeeding duration.40 Overall, the more of the Baby Friendly 10 Steps that dyads experience, the greater the prevalence of breastfeeding.41

Conclusions

Decisions about appropriate postnatal unit arrangements should take into account that families will have individualized needs. Acknowledgement of the risks associated with cesarean do not currently extend to breastfeeding disruption or infant handling issues,7 despite the extensive debate over the trade-offs of cesarean in relation to vaginal birth.42–43 The stand-alone bassinet may not just be inconvenient for mothers after a cesarean, it may be an unnecessary breastfeeding obstacle and institutionalized risk for infants.

Well Established

Rooming-in promotes breastfeeding. Previous research found side-cars (three-sided bassinets that lock onto the maternal bed frame) faciliate breastfeeding after vaginal birth compared to stand-alone bassinets (rooming-in). The pathways to ameliorating suboptimal breastfeeding after cesarean are unclear.

Newly Expressed

Following cesarean birth, stand-alone bassinets may present an unnecessary breastfeeding obstacle and post a hazard for infants because of mothers’ compromised mobility during the early postpartum period.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Owen F. Aldis Fund of the International Society for Human Ethology. Kristin P. Tully is currently supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Training Grant 2T32HD007376-21A1.

The authors thank Martin Ward Platt, Diane Holditch-Davis, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful contributions.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Kristin P. Tully, Carolina Consortium on Human Development, Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Helen L. Ball, Department of Anthropology, Director, Parent-Infant Sleep Laboratory, Fellow, Wolfson Research Institute for Health & Wellbeing, Durham University.

References

- 1.Chertok IR. Breast-feeding initiation among post-caesarean women of the Negev, Israel. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(4):205–208. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.4.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Declercq E, Cunningham DK, Johnson C, Sakala C. Mothers’ reports of postpartum pain associated with vaginal and cesarean deliveries: Results of a national survey. Birth. 2008;35(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlström A, Engström-Olofsson R, Norbergh K-G, Sjöling M, Hildingsson I. Postoperative pain after cesarean birth affects breastfeeding and infant care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(5):430–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, et al. Rates of caesarean section: Analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(2):98–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Declercq E, Young R, Cabral H, Ecker J. Is a rising cesarean delivery rate inevitable? Trends in industralized countries, 1987 to 2007. Birth. 2011;38(2):99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menacker F, Hamilton BE. NCHS Data Brief, No 35. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Mar, 2010. [Accessed January 14, 2012]. Recent trends in cesarean delivery in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db35.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Caesarean Section (update) [Accessed January 14, 2012];Clinical Guideline CG132. Updated November 2011. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG132.

- 8.Rowe-Murray HJ, Fisher JRW. Operative intervention in delivery is associated with compromised early mother-infant interaction. BJOG. 2001;108(10):1068–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Declercq E, Labbok MH, Sakala C, O’Hara M. Hospital practices and women’s likelihood of fulfilling their intention to exclusively breastfeed. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):929–935. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig J, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):607–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venancio SI, Saldiva SRDM, Mondini L, Levy RB, Escuder MML. Early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors, state of São Paulo, Brazil. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(2):168–174. doi: 10.1177/0890334408316073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Authors. Trade-offs underlying maternal breastfeeding decisions: A conceptual model. Matern Child Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Ríos N, Ramos-Valencia G, Ortiz AP. Cesarean delivery as a barrier for breastfeeding initiation: The Puerto Rican experience. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(3):293–302. doi: 10.1177/0890334408316078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith AHK, Dixon AL, Page LA. Health-care professionals’ views about safety in maternity services: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2009;25(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel RR, Liebling RE, Murphy DJ. Effect of operative delivery in the second stage of labor on breastfeeding success. Birth. 2003;30(4):255–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolan A, Lawrence C. A pilot study of a nursing intervention protocol to minimize maternal-infant separation after cesarean birth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(4):430–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Accessed January 14, 2012]. http://www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/9241562218/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaus MH, Kennell JH. Maternal-Infant Bonding: The Impact of Early Separation or Loss on Family Development. St. Louis, MO: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnusson D, Cairns RB. Developmental science: Toward a unified framework. In: Cairns RB, Elder GH, Costello EJ, editors. Developmental Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenna JJ, Mosko SS, Richard CA. Bedsharing promotes breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 1997;100(2):214–219. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball HL, Ward-Platt MP, Heslop E, Leech SJ, Brown KA. Randomised trial of infant sleep location on the postnatal ward. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(12):1005–1010. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.099416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ball HL. Evolutionary paediatrics: A case study in applying Darwinian medicine. In: Elton S, O’Higgins SP, editors. Medicine and Evolution: Current Applications, Future Prospects. London: CRC Press; 2008. pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jolivet RR, Corry MP, Sakala C. Transforming maternity care: Key informant interview summary. Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20(1 Suppl):S79–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monson SA, Henry E, Lambert DK, Schmutz N, Christensen RD. In-hospital falls of newborn infants: Data from a multihospital health care system. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e277–e280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bragg F, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, et al. Variation in rates of cesarean section among English NHS Trusts after accounting for maternal and clinical risk: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ball HL, Ward-Platt MP, Howel D, Russell C. Randomised trial of sidecar crib use on breastfeeding duration (NECOT) Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):630–634. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.205344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eibl-Eibesfeldt I. Human Ethology: Foundations of Human Behavior. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin P, Bateson P. Measuring Behaviour. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson S. Focus group research. In: Silverman D, editor. Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice. 2. London: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummins S, Curtis S, Diez-Roux AV, Macintyre S. Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1825–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredriksson GEM, Högberg U, Lundman BM. Postpartum care should provide alternative to meet parents’ need for safety, active participation, and ‘bonding. ’ Midwifery. 2003;19(4):267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(03)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dykes F. Breastfeeding in Hospital: Mothers, Midwives and the Production Line. London: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman D. Who cares about experience? Missing issues in qualitative research. In: Silverman D, editor. Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice. 2. London: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 342–367. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trevathan WR. Human Birth: An Evolutionary Perspective. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison B, Ludington-Hoe S, Anderson GC. Interruptions to breastfeeding dyads on postpartum day 1 in a university hospital. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(6):709–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Accessed January 14, 2012]. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/924159084X/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Evanson-Coombe C, Edmonds M, Heckstall-Smith EMA, Fleming P. Hazardous cosleeping environments and risk factors amenable to change: Case-control study of SIDS in south west England. BMJ. 2009;339:b3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith L. Physics, forces, and mechanical effects of birth on breastfeeding. In: Kroeger M, editor. Impact of Birthing Practices on Breastfeeding: Protecting the Mother and Baby Continuum. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2004. pp. 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bystrova K, Ivanova V, Edhorg M, et al. Early contact versus separation: effects on mother-infant interaction one year later. Birth. 2009;36(2):91–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikiel-Kostyra K, Mazur J, Boltruszko I. Effect of early skin-to-skin contact after delivery on duration of breastfeeding: A prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91(12):1301–1306. doi: 10.1080/08035250216102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiGirolamo AM, Grummer-Strawn LM, Fein SB. Effect of maternity-care practices on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S43–S49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ecker JL, Frigoletto FD. Cesarean delivery and the risk-benefit calculus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(9):885–888. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalish RB, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. Patient choice cesarean delivery: Ethical issues. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20(2):116–119. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282f55df7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]