Abstract

Objectives

To characterize variation and inequalities in neighborhood child asthma admission rates and to identify associated community factors within one US county.

Study design

This population-based prospective, observational cohort study consisted of 862 sequential child asthma admissions among 167 653 eligible children ages 1-16 years in Hamilton County, Ohio. Admissions occurred at a tertiary-care pediatric hospital and accounted for nearly 95% of in-county asthma admissions. Neighborhood admission rates were assessed by geocoding addresses to city- and county-defined neighborhoods. The 2010 US Census provided denominator data. Neighborhood admission distribution inequality was assessed by the use of Gini and Robin Hood indices. Associations between neighborhood rates and socioeconomic and environmental factors were assessed using ANOVA and linear regression.

Results

The county admission rate was 5.1 per 1000 children. Neighborhood rates varied significantly by quintile: 17.6, 7.7, 4.9, 2.2, and 0.2 admissions per 1000 children (P < .0001). Fifteen neighborhoods containing 8% of the population had zero admissions. The Gini index of 0.52 and Robin Hood index of 0.38 indicated significant inequality. Neighborhood-level educational attainment, car access, and population density best explained variation in neighborhood admission rates (R2 = 0.55).

Conclusion

In a single year, asthma admission rates varied 88-fold across neighborhood quintiles in one county; a reduction of the county-wide admission rate to that of the bottom quintile would decrease annual admissions from 862 to 34. A rate of zero was present in 15 neighborhoods, which is evidence of what may be attainable.

Although asthma is one of the most common chronic illnesses of childhood, morbidity is not equally shared across populations.1,2 Deep, preventable disparities exist in the frequency of acute asthma exacerbations, with morbidity clustering within disadvantaged populations and communities.3-6 Such high-risk populations often are concentrated within geographic areas affected by factors such as low household income, unemployment, limited access to transportation, poor-quality housing, and crowded conditions within the home.7-15 Observed disparities have been explained, in part, by these socioeconomic and home environmental risk factors and by their interaction with an individual’s atopic or genetic predisposition.16

Currently, researchers are focusing on the identification of disease “hot-spots” to inform targeted community-based interventions.17-19 Considerably less attention has been paid to low-risk, “cold-spot” communities, even though they represent the health that could theoretically be obtained across a region. Similarly, medical research has rarely focused on objective measures of inequality across high- and low-risk areas. Inequality measures, including the Gini and Robin Hood indices, commonly are used to characterize income inequalities, but they have not been routinely used to capture inequalities in health outcomes.20-22

Understanding the drivers of health inequalities requires the identification and use of informative geographic boundaries.23 The geographic distribution of childhood asthma has been studied with the use of zip codes as well as individual and spatially aggregated census tracts.8-11,24 Zip codes, which were designed for efficient delivery of mail, are often heterogeneous with respect to social and environmental factors.25 Census tracts, although smaller and more homogenous, do not always align with community-accepted neighborhood boundaries. Few studies have used boundaries defined by the community to define the distribution of asthma morbidity.26

In this study, we first sought to delineate variability in neighborhood asthma admission rates within a single Mid-western county that is characterized by geographic, socioeconomic, and demographic diversity. The identification of asthma morbidity “hot-” and “cold-” spots through the use of community-accepted neighborhood boundaries is new in the pediatric asthma literature, and we anticipated that it would frame neighborhood-based interventions in new, community-focused ways. Second, we sought to illustrate and calculate distribution inequalities in the admissions of children for asthma by using the Gini and Robin Hood indices in novel ways. Finally, we sought to identify neighborhood-level characteristics that may contribute to observable neighborhood variability in asthma admissions and may present targets for future intervention.

Methods

Data were analyzed as part of the population-based prospective, observational Greater Cincinnati Asthma Risks Study (GCARS) cohort. The GCARS enrolled children who were admitted for asthma or bronchodilator-responsive wheezing to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), an urban, tertiary-care, stand-alone pediatric hospital. The cohort was limited to children between 1 and 16 years of age for several reasons. One, for children younger than 1 year of age, there is the potential for diagnostic overlap. Two, for older children, a greater proportion may obtain inpatient care at alternative institutions and therefore be lost to follow-up.

Between September 1, 2010, and August 31, 2011, eligible children were identified on the basis of admission diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, 493.XX) and use of the evidence-based clinical pathway for acute asthma care by the admitting physician. Children were excluded if they were removed from the asthma pathway after further diagnostic consideration or if they had significant respiratory or cardiovascular comorbidity (eg, cystic fibrosis, congenital heart disease). For this study, analysis was limited to patients from CCHMC’s home county, Hamilton County, an area with nearly 170 000 children ages 1-16 years, so as to further limit admissions lost to other institutions.27 Given data from the Ohio Hospital Association indicating that nearly 95% of all in-county asthma admissions for children ages 1-16 years occur at CCHMC facilities, our accrued admission sample was considered to be population-based.28 Demographic data, including home address, were collected from the electronic health record. The CCHMC Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Calculation of Neighborhood Admission Rates

The home address for each admission event was geocoded with ArcGIS software (Version 10; Redlands, California). Greater than 99% of addresses were geocoded to the rooftop or street level and assigned to a locally defined neighborhood. In the City of Cincinnati, the Department of City Planning and Buildings defines “statistical neighborhood areas,” composed of census tracts or parts of census tracts, to approximate local neighborhood boundaries accepted by citizens and community councils.29 The Hamilton County Planning and Development Department oversees boundaries for municipalities and townships outside of city limits.30 Such areas are used by city and county governments to guide planning activities and enforce regulations in ways that encourage participation from the communities involved.

We identified 93 neighborhoods primarily within Hamilton County. Three fell within a single census tract and were treated as a single neighborhood. Admission rates were calculated for Hamilton County as a whole and for each of the defined 91 in-county neighborhoods. The total number of admission events was then divided by the total number of children ages 1-16 years within the defined geographic area to calculate the neighborhood admission rate. Population denominators were calculated using values obtained from the 2010 US Census Summary File 1.27 Neighborhoods were then sorted by their admission rate and grouped into admission rate quintiles such that each quintile included 20% of all neighborhoods. Quintiles were used to stabilize admission rate estimates, given the relatively small population sizes in certain neighborhoods.

Neighborhood-Level Measures

Neighborhood-level differences between admission rate quintiles were assessed by the use of neighborhood-level measures, chosen a priori to align with asthma-related socioeconomic and environmental factors, that were calculated from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey.27 Measures for multiple census tracts, or parts of census tracts, were combined with weighted averaging.

Neighborhood-level markers of socioeconomic status (SES) included median household income and the percentage of individuals living below the poverty line11,13,14,31; neighborhood-level educational attainment was defined as the percentage of adults (≥25 years) with at least a college education.32 Neighborhood-level unemployment31 and the percentage of households without access to a car were also assessed.5 Neighborhood-level home environmental markers were median home value, the percentage of renter-occupied and vacant homes, and population density, measured as the number of persons per square mile.5,12,24

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics provided basic demographic information for individual children admitted to CCHMC facilities during the 1-year period. Neighborhood admission rate quintiles were compared with ANOVA.

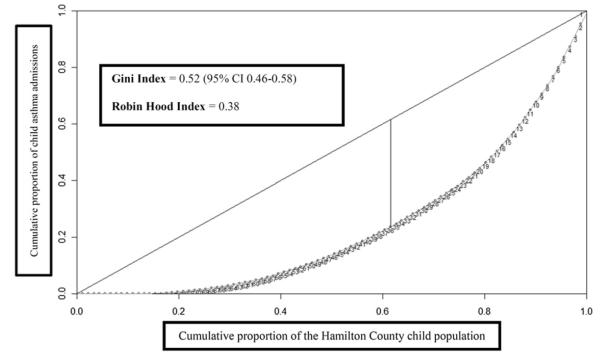

Inequalities in admission distribution across Hamilton County were assessed with the use of inequality indices that can be calculated from the Lorenz curve. To construct the curve, neighborhoods were ordered by their admission rates from lowest to highest. Then, the cumulative proportion of all 167 653 children contributed by each neighborhood was measured on the x-axis and the cumulative proportion of all 862 admissions on the y-axis. Once plotted, the Lorenz curve allows for calculation of the Gini and Robin Hood inequality indices. The Gini index, ranging between 0 and 1, is calculated from the area between the Lorenz curve and the 45° diagonal. If the curve overlies the diagonal, with 50% of children contributing 50% of admissions, the Gini index will equal zero, and there is perfect equality. A value approaching one signifies much greater bowing away from the diagonal and indicates increasing inequality. The Robin Hood index approximates the proportion of admissions that would need to be redistributed from high to low admission rate neighborhoods to eliminate observed inequalities.20

Differences between admission rate quintiles with respect to census data were assessed with ANOVA. We also assessed relationships between neighborhood admission rates, on a continuous scale, and underlying neighborhood-level measures using Pearson correlation coefficients. Neighborhood admission rate distribution was then normalized with a square-root transformation, and the subset of neighborhood-level measures that best explained variation was identified using backward selection in linear regression. These analyses were not weighted by neighborhood population size.33 A sensitivity analysis with an untransformed Poisson regression did account for population differences. For analyses, we used SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R statistical software (The R Project for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria).

Results

There were 862 admission events, corresponding to 757 children, across the 91 neighborhoods over 1 year. Admitted children had a mean age of 6.5 years (SD 4.2) and were 64% male, 71% African American, and 75% publically insured by Medicaid or equivalent.

Variation in Neighborhood Admission Rates

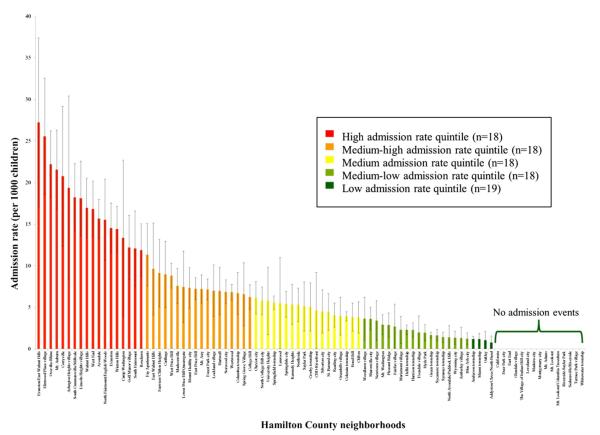

The county admission rate was 5.1 admissions per 1000 children. Admission rates varied substantially between neighborhoods, ranging from 27.2 to 0 admissions per 1000 children (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Rates also varied significantly by neighborhood quintile: 17.6, 7.7, 4.9, 2.2, and 0.2 admissions per 1000 children for the highest to lowest neighborhood quintiles, respectively (P < .0001). The greatest rates of admission appeared to concentrate in Cincinnati’s urban core in close proximity to CCHMC.

Figure 1.

Distribution of asthma admission rates within Hamilton County (n = 91 neighborhoods).

Distribution of Asthma Admissions across Neighborhoods

The highest neighborhood quintile had an asthma admission rate 88 times greater than that of the lowest quintile (17.6 vs 0.2 admissions per 1000 children). The quintile with the greatest admission rate contributed 11% of county children but 35% of all admissions. In contrast, the quintile with the lowest admission rate quintile contributed 17% of county children and 2% of admissions. Fifteen neighborhoods, representing 8% of children, had zero admissions.

The inequality in admission distribution is illustrated by the Lorenz curve (Figure 2). The Gini index for the distribution of admissions within Hamilton County was 0.52 (95% CI 0.46-0.58). The Robin Hood index was 0.38, meaning that 38% of all admissions would need to be redistributed from neighborhoods with the greatest admission rates to neighborhoods with the lowest admission rates for equal admission distribution to be achieved.

Figure 2.

Lorenz curve used to calculate the Gini and Robin Hood indices. Each numbered point along the curve represents a single Hamilton County neighborhood, ordered by ascending admission rate. The Gini index was calculated from area between the Lorenz curve and the diagonal, and the Robin Hood index was calculated from the maximum vertical height between the Lorenz curve and the diagonal.

Underlying Neighborhood-Level Characteristics

There were significant differences between quintiles with respect to potentially underlying neighborhood-level characteristics (Table). For example, in the quintile with the greatest admission rate, the mean of median household incomes was $23 908, which approximates the federal poverty level for a family of 4.34 In contrast, the quintile with the lowest admission rate had a household income of greater than $80 000, with household income related to each quintile in a graded fashion (P < .0001). Similar graded relationships were noted for the other neighborhood markers of SES (all P < .0001). Home environmental markers also were found to differ significantly across quintiles (all P ≤ .01). As an example, the mean of median home values within the quintile with the greatest admission rate was roughly one-third that of the quintile with the lowest admission rate ($101 288 vs $270 184; P < .0001).

Table.

Ecological associations and correlations between neighborhood admission rates and 2006-2010 US Census American Community Survey variables aggregated to the neighborhood level

| Neighborhood admission rate quintile* |

Continuous admission rate |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census variable | High | Medium-high | Medium | Low-medium | Low | P † | Correlation coefficient‡ | P ‡ |

| Neighborhood markers of SES | ||||||||

| Household income, USD | $23 908 | $33 909 | $42 141 | $70 452 | $80 199 | <.0001 | −0.57 | <.0001 |

| Individuals below poverty line, % | 40.4 | 28.5 | 16.7 | 7.8 | 11.3 | <.0001 | 0.66 | <.0001 |

| Adults with college education or greater, %§ | 15.4 | 22.3 | 26.4 | 46.01 | 47.3 | <.0001 | −0.49 | <.0001 |

| Unemployment rate, % | 16.1 | 13.7 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 7.2 | <.0001 | 0.44 | <.0001 |

| Households without access to a car, %§ | 33.4 | 21.5 | 14.1 | 5.1 | 5.3 | <.0001 | 0.67 | <.0001 |

| Neighborhood markers of surrounding environment | ||||||||

| Home value, USD | $101 288 | $113 174 | $138 438 | $206 479 | $270 184 | <.0001 | −0.40 | <.0001 |

| Renter occupied homes, % | 65.7 | 69.5 | 54.3 | 38.8 | 46.2 | .0024 | 0.30 | .0039 |

| Vacant homes, % | 28.7 | 18.4 | 12.6 | 8.1 | 10.7 | <.0001 | 0.65 | <.0001 |

| Population density (persons/square mile)§ | 3805 | 3351 | 3225 | 2101 | 2043 | .013 | 0.35 | .0008 |

USD, US dollars.

Value for each census variable presented as a mean for the neighborhood quintile.

Calculated from ANOVA.

Pearson correlation coefficient between neighborhood admission rate on a continuous scale and census variable.

Variables remaining in a linear regression model after backward selection (R2 = 0.55).

Neighborhood-level markers of SES and the home environment were significantly correlated with neighborhood admission rates on a continuous scale (all r ≥ 0.3; P < .01; Table). Admission rate was most strongly correlated with a neighborhood’s percentage of individuals below the poverty line (r = 0.66; P < .0001), percentage of households without access to a care (r = 0.67; P < .0001), and percentage of vacant homes (r = 0.65; P < .0001). Three factors remained independently associated with admission rates in a linear regression model: the percentage of adults with a college education, the percentage of households without access to a car, and population density (R2 = 0.55). A sensitivity analysis in which we used population-weighted Poisson regression produced consistent effect sizes at the same significance levels.

Discussion

Using locally defined and accepted neighborhoods as our unit of analysis, we found that the highest neighborhood quintile had an admission rate for asthma or bronchodilator-responsive wheezing that was 88 times that of the lowest quintile. In addition, 15 neighborhoods had zero admission events. Successful reduction of the county-wide admission rate to that of the bottom quintile would eliminate disparities in asthma admission rates and decrease annual admissions by 96%. This inequality in the distribution of admissions was associated with underlying differences in potentially modifiable neighborhood-level socioeconomic and environmental factors, suggesting that genes alone are unlikely to explain this variation.

Hamilton County had an asthma admission rate double the nationwide rate of 2.5 per 1000, and some neighborhoods had rates more than 10 times the national average.1,2 If the county-wide admission rate was reduced to match the rate of the lowest admission rate quintile, total annual admissions would be reduced from 862 to 34. More conservatively, if the county-wide rate was that of the median neighborhood (2.0 per 1000 children), admissions would still be reduced by greater than 50%, from 862 to 336.

Observed differences exceed disparities found in prior studies of asthma prevalence and morbidity.11 For example, an 8-fold difference in rates of childhood asthma hospitalization was demonstrated across St. Louis zip codes.8 Similarly, child asthma hospitalization “hot-spots” in New York City were identified by the use of spatially aggregated census tracts and were found to have hospitalization rates 3-4 times greater than areas outside “hot-spots.”10 We expect that our incounty findings, and the concentration of morbidity in the urban core, mirror those across the country with region-specific factors influencing the degree to which disparities are manifested. We also expect that the relative homogeneity (or heterogeneity) of the chosen geography influences the magnitude of the identified disparity.

Although zip codes and census tracts are reasonable and relevant geographies, the use of neighborhoods has the potential to be more readily translatable to community-based interventions.26,35 Zip codes are limited by their heterogeneity, and census tracts may not be easily identified by community members.25,26 We used neighborhood boundaries defined by local planning commissions and accepted by local citizens and community councils to compare locally identifiable populations. Speaking a common geographic language could more easily engage and motivate communities to collectively seek community-based improvement.

Community-based health improvements also can be informed by clearer depictions of health inequalities, much the way depictions of socioeconomic inequalities have informed social policy changes (eg, Earned Income Tax Credit to increase income for the working poor).36,37 The calculated inequality in the distribution of Hamilton County’s admissions for children with asthma was on par with income inequality in the most unequal nations in the world (eg, Brazil at 0.52).38 It also exceeds income inequality measured for both the US (Gini = 0.47) and its most unequal counties (eg, Hamilton County’s Gini = 0.49).27 The calculated Robin Hood index for the distribution of asthma admissions within Hamilton County was 0.38. Previously published Robin Hood indices for the distribution of income in the US have suggested that roughly 30% of all income would need to be transferred from the wealthy to the poor to reach equality.39

The use of the Lorenz curve to describe inequalities in the distribution of health outcomes and resources is gaining prominence. For example, the Gini index has been used to measure the distribution of dentists across Japan40 and obesity across a region.41 Others have used the Gini to assess geographic distribution of sexually transmitted infections in Manitoba (Gini = 0.66 for gonorrhea).42 This study is the first, however, to use the Lorenz curve to assess geographic inequalities in child asthma morbidity. It is a step toward standardized assessment of health inequalities that uncouples inequality from income and grounds it in well-being and potentially modifiable neighborhood-level factors.

Understanding these underlying neighborhood-level characteristics may help identify targets for interventions that may ultimately reduce inequalities. For this analysis, we assessed neighborhood factors related to SES that have been shown to impact the prevalence of and morbidity from asthma.5,9,11,15,24,31,32 Neighborhoods in the quintile with the greatest admission rate had an aggregated household income close to the federal poverty line, and there were also strong graded relationships between neighborhood quintile and other markers of SES. These findings are consistent with previous accounts in which authors detail the convergence of poverty and morbidity,6 and such findings may identify areas amenable to tailored interventions. For example, if neighborhoods with high admission rates are found to have low rates of car access, perhaps interventions such as point-of-care or mailed medications or home health pathways may be appropriate. Additional factors that include the availability and accessibility of pharmacies, primary care, and subspecialty care also may affect observed inequalities and be potential avenues for future intervention.

We also assessed factors related to quality of the surrounding environment that have been linked to asthma-related morbidity through dilapidated, substandard housing, and crowding.5,12,24,43 Neighborhoods in the quintile with the greatest rates of admission had significantly lower home values, greater rates of rented and vacant homes, and greater population densities. Given the strong association between housing quality and asthma, we expect the inequalities identified are, in part, influenced by neighborhood housing stock and living conditions.12 Future studies in which authors assess neighborhood housing type (eg, single vs multifamily) or quality (eg, density of housing code violations) could more directly characterize the housing–asthma intersection and inform neighborhood-based interventions. Such interventions could include the mobilization of health and building departments or legal aid attorneys, potentially reducing the burden of environmental exposures and improving asthma outcomes.5 Further characterization of underlying gene–environment interactions could also help to identify patient- or community-based interventions aimed at reducing preventable admissions.

There were limitations to this study. First, population denominators differed from one neighborhood to another. The stability of the admission rate for each individual neighborhood, therefore, may vary with time. Analyses in which we used aggregated quintiles likely stabilized the observed rates. Second, we are unable to tell from these data what the underlying neighborhood-to-neighborhood variation was with respect to baseline asthma prevalence. Given a national pediatric asthma prevalence of 9.5%,2 it is unlikely that asthma was rare or nonexistent in neighborhoods contributing few (or no) admissions. Third, findings from analyses of neighborhood-level characteristics may have been influenced by varying neighborhood population sizes. Still, the innovation in the use of readily identifiable neighborhoods as our unit of measure and the consistency identified by the use of weighted analyses supported our decision to forego population weighting.33 Fourth, asthma admission data were only available for children hospitalized at CCHMC facilities; children may have been admitted elsewhere. Local data indicate, however, that CCHMC cares for nearly 95% of all in-county childhood asthma admissions.28 Fifth, this study illustrates associations, not causation, between admission rates and underlying neighborhood-level characteristics. Finally, our population drew from a single county and may not be generalizable to other regions.

We expect, however, that with the advent of electronic health records and the easy accessibility of patient addresses, our methodology could be readily implemented in many settings, especially those regions oriented and organized around neighborhoods. We also expect that refined neighborhood “phenotypes” that delineate community-level risks and assets44 could inform community-hospital collaboration aimed at disparity reduction for asthma and other conditions (eg, prematurity, injury, and obesity).

In a single year, the admission rates of children with asthma showed substantial variation across neighborhoods within a single county, highlighting a degree of child health inequality exceeding that of US income inequality. Neighborhood admission rate variation was strongly associated with underlying differences in neighborhood-level characteristics related to both SES and the surrounding environment. The low rates of admission in certain neighborhoods, including the 15 neighborhoods with a zero rate, represent what may be attainable through efforts aimed at disparity reduction.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Bureau of Health Professions (BHPR), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), under the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) NRSA Primary Care Research Fellowship in Child and Adolescent Health (T32HP10027). The Greater Cincinnati Asthma Risks Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01AI88116 [PI: R.S.; Co-PI: A.B., J.S., T.M., and B.H.]). Use of REDCap was supported by the National Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training (UL1-RR026314-01). The information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPR, HRSA, DHHS, or the US government.

We thank Kelly Antony for database management, David Jones and Patrick Ryan for their expertise in geographic information systems, and GCARS clinical research coordinators Emily Greenberg, Angela Howald, Elizabeth Monti, Stacey Rieck, and Heather Strong for their support and dedication.

Glossary

- CCHMC

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

- GCARS

Greater Cincinnati Asthma Risks Study

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Footnotes

These data were previously presented as an abstract at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ Meeting, April 28-May 1, 2012, Boston, MA.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of childhood asthma in the United States, 1980-2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123(Suppl 3):S131–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, et al. National Surveillance of Asthma: United States, 2001-2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2012:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Seifer R, Kopel SJ, Esteban C, Canino G, et al. Multiple urban and asthma-related risks and their association with asthma morbidity in children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:582–95. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour ME, Lanphear BP, DeWitt TG. Barriers to asthma care in urban children: parent perspectives. Pediatrics. 2000;106:512–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persky V, Turyk M, Piorkowski J, Coover L, Knight J, Wagner C, et al. Inner-city asthma: the role of the community. Chest. 2007;132:831S–9S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. Social determinants: taking the social context of asthma seriously. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S174–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ash M, Brandt S. Disparities in asthma hospitalization in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:358–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro M, Schechtman KB, Halstead J, Bloomberg G. Risk factors for asthma morbidity and mortality in a large metropolitan city. J Asthma. 2001;38:625–35. doi: 10.1081/jas-100107540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claudio L, Stingone JA, Godbold J. Prevalence of childhood asthma in urban communities: the impact of ethnicity and income. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corburn J, Osleeb J, Porter M. Urban asthma and the neighbourhood environment in New York City. Health Place. 2006;12:167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta RS, Zhang X, Sharp LK, Shannon JJ, Weiss KB. Geographic variability in childhood asthma prevalence in Chicago. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:639–45.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauh VA, Landrigan PJ, Claudio L. Housing and health: intersection of poverty and environmental exposures. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:276–88. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankardass K, Jerrett M, Milam J, Richardson J, Berhane K, McConnell R. Social environment and asthma: associations with crime and No Child Left Behind programmes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:859–65. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.102806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenfeld L, Rudd R, Chew GL, Emmons K, Acevedo-Garcia D. Are neighborhood-level characteristics associated with indoor allergens in the household? J Asthma. 2010;47:66–75. doi: 10.3109/02770900903362676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin S, Fitzgerald E, Hwang SA, Munsie JP, Stark A. Asthma hospitalization rates and socioeconomic status in New York State (1987-1993) J Asthma. 1999;36:239–51. doi: 10.3109/02770909909075407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill TD, Graham LM, Divgi V. Racial disparities in pediatric asthma: a review of the literature. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N. Place, space, and health: GIS and epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2003;14:384–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000071473.69307.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berke EM. Geographic Information Systems (GIS): recognizing the importance of place in primary care research and practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:9–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.01.090119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark N, Lachance L, Milanovich AF, Stoll S, Awad DF. Characteristics of successful asthma programs. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:797–805. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee WC. Characterizing exposure-disease association in human populations using the Lorenz curve and Gini index. Stat Med. 1997;16:729–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970415)16:7<729::aid-sim491>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. The relationship of income inequality to mortality: does the choice of indicator matter? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1121–7. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1783–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu SY, Pearlman DN. Hospital readmissions for childhood asthma: the role of individual and neighborhood factors. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:65–78. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N, Waterman P, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Zip code caveat: bias due to spatiotemporal mismatches between zip codes and US census-defined geographic areas–the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1100–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cromley EK. Breadth and depth in research on health disparities: commentary on the work of Nancy Krieger. GeoJournal. 2009;74:115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed February 1, 2012];2012 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- 28.Bosnjakovic E. INSIGHT Database. Ohio Hospital Association; Columbus, OH: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.City Planning and Buildings. City of Cincinnati; Cincinnati, Ohio: [Accessed February 1, 2012]. 2012. http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/planning/reports-data/census-demographics/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Planning and Development. Hamilton County, Ohio: [Accessed February 1, 2012]. 2012. http://www.hamiltoncountyohio.gov/pd/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kub J, Jennings JM, Donithan M, Walker JM, Land CL, Butz A. Life events, chronic stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income urban mothers with asthmatic children. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cesaroni G, Farchi S, Davoli M, Forastiere F, Perucci CA. Individual and area-based indicators of socioeconomic status and childhood asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:619–24. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00091202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frohlich N, Carriere KC, Potvin L, Black C. Assessing socioeconomic effects on different sized populations: to weight or not to weight? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:913–20. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.12.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; Washington, DC: [Accessed February 1, 2012]. 2012. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soobader M, Cubbin C, Gee GC, Rosenbaum A, Laurenson J. Levels of analysis for the study of environmental health disparities. Environ Res. 2006;102:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ. 1997;314:1037–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CIA World Factbook - Distribution of family income - Gini index. Central Intelligence Agency; Washington, DC: [Accessed February 1, 2012]. 2012. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ. 1996;312:1004–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okawa Y, Hirata S, Okada M, Ishii T. Geographic distribution of dentists in Japan: 1980-2000. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:236–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slater J, Green C, Sevenhuysen G, O’Neil J, Edginton B. Socio-demographic and geographic analysis of overweight and obesity in Canadian adults using the Canadian Community Health Survey (2005) Chronic Dis Can. 2009;30:4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elliott LJ, Blanchard JF, Beaudoin CM, Green CG, Nowicki DL, Matusko P, et al. Geographical variations in the epidemiology of bacterial sexually transmitted infections in Manitoba, Canada. Sex Transmit Infect. 2002;78:i139–44. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohn RD, Arbes SJ, Jr, Jaramillo R, Reid LH, Zeldin DC. National prevalence and exposure risk for cockroach allergen in U.S. households. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:522–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta RS, Zhang X, Sharp LK, Shannon JJ, Weiss KB. The protective effect of community factors on childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1297–304.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]