Abstract

A biosensor based on an array of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers (CNFs) grown by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition is found to be effective for the simultaneous detection of dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) in the presence of excess ascorbic acid (AA). The CNF electrode outperforms the conventional glassy carbon electrode (GCE) for both selectivity and sensitivity. Using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), three distinct peaks are seen for the CNF electrode at 0.13 V, 0.45 V, and 0.70 V for the ternary mixture of AA, DA, and 5-HT. In contrast, the analytes are indistinguishable in a mixture using a GCE. For the CNF electrode, the detection limits are 50 nM for DA and 250 nM for 5-HT.

Keywords: Biosensor, Dopamine, Serotonin, Carbon nanofiber, Nanoelectrode array

1. Introduction

Dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) are neurotransmitters in the brain that are implicated in a number of human pathologies. DA levels have been tied to addiction, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy, among many other disorders. Levels of 5-HT are linked to depression, addiction, and other functions ranging from appetite to sleep. Simultaneous measurement of DA and 5-HT is particularily important since these molecules typically coexist and their relative levels have implications in many diseases and reponse to drug treatments (Kapur and Remington, 1996; Swamy and Venton, 2007). Traditional detection methodologies have employed voltammetric techniqes since DA and 5-HT are electroactive with easily measured anodic oxidation (Adams, 1976). Advantages of electrochemical detection include fast response time and easy miniaturization of equipment. However, these techniques often suffer from a lack of selectivity; for example, DA and 5-HT have a similar oxidation potential, E0, varying by less than 150 mV (E0(DA) = 200 mV and E0(5-HT) = 320 mV versus Ag/AgCl), making them indistinguishable using many traditional electrode materials (Kovach et al., 1984). In addition, ascorbic acid (AA) is a common interferrent that coexists with DA and 5-HT in the brain at concentrations 100–1000 times higher than that of DA (Stamford and Justice, 1996; Wightman et al., 1988; Zen and Chen, 1997).

Previously, neurotransmitters were separated by liquid chromatography (Sasa and Blank, 1977) or capillary electrophoresis (Wallingford and Ewing, 1989) prior to electrochemical detection. More recently, electrode modification through the addition of nafion (Gerhardt et al., 1984; Baur et al. 1988), overoxidized polypyrrole (Piehl et al., 1996; Hu et al. 2007; Shang et, al., 2009) and clay (Zen and Chen, 1997) or electrochemical pretreatments (Gonon et al., 1981) were used to change the electrode’s surface charge and therefore block anionic molecules such as AA and attract cationic molecules such as DA. However, the advantageous effects of these pre-treatments are short-lived as these materials break down and the suface charge is neutralized (Gonon et al., 1981). Carbon nanotubes have been used to modify carbon fiber (Swamy and Venton, 2007), graphite (Wang et al., 2002), carbon paste (Huang et al., 2008) and glassy carbon electrodes (Wu et al., 2003; Alwarappan et al. 2009; Alwarappan et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2001) to increase the selectivity of DA in mixtures by increasing DA adsorption sites and decreasing oxidation overpotentials. Graphene-modified glassy carbon was shown to have better stability and higher signal-to-noise when used to detect DA and 5-HT in the prescence of AA when compared to single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) -modfied glassy carbon (Alwarappan et al., 2009). This difference was attributed to the higher abundance of sp2 carbon in the graphene versus the SWCNT.

As-grown, free-standing, vertical carbon nanofibers (CNFs) grown by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) have garnered attention for numerous applications (Meyyappan et al., 2003); in particular they are considered as effective electrodes because of their high conductivity combined with a high percentage of surface defects containing COOH functionality, which is thought to enhance electron transfer and selectively differentiate catecholamines and their interferrents. Previously, CNF based biosensors have shown high senstivity, high spatial resolution, good biocompatability (Koehne et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Nguyen-Vu et al.) and have been fabricated into a 3x3 array for multiplexing capability (Aramugam et al., 2009). In this article, we demonstrate the use of as-grown, free standing CNFs as nanoelectrodes to selectively measure DA, down to 50 nM, and 5-HT, down to 100 nM, in the prescence of AA.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Preparation of CNF Electrodes

CNFs were grown directly on silicon substrates by PECVD from a 20 nm thick layer of nickel catalyst on 200 nm chromium (Alfa Aesar), as previously described (Arumugam et al., 2009). A dc-biased plasma reactor (Aixtron, Cambridge, UK) was used to grow the CNFs using 125 sccm acetylene and 144 sccm of ammonia as feedstock at 6.3 mbar, 700°C and 180 W power. The growth time was 6 minutes producing fibers of ~5 μm height.

2.2 Characterization of CNFs

Electron microscopy characterization was performed with a Hitachi S4800 scanning electron microscope (SEM) and a Hitachi H9500 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Hitachi, Pleasanton, CA). Raman studies were carried on a Renishaw inVia micro-Ramanspectrometer (Renishaw plc, Gloucestershire, UK) using 514 nm excitation and the optical power delivered onto the sample was 50 mW/cm2. IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Magna IR 550 spectrometer equipped with DTGS/KBr detector and windows with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1. For FT-IR spectroscopy characterization, the nanofibers were first scraped off of silicon substrate and suspended in acetone before being drop-cast onto PTFE windows. The FTIR spectra were collected in transmission mode.

2.3 Electrochemistry

All the electrochemical measurements were performed using an Autolab PGSTAT12 and PGSTAT128N (Metrohm USA, Minneapolis, MN). Measurements were taken using both two electrode or three electrode configurations with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a platinum counter electrode and either a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or CNF working electrode. The Ag/AgCl reference electrode was prepared by chlorination in bleach using a Ag wire (Alfa Aesar). The GCE used here for comparison was a conventional disc electrode with a diameter of 1 mm. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with a 20 mV modulation amplitude and 5 mV step potential was used to characterize DA and 5-HT detection.

The carbon electrodes were pre-conditioned prior to electrochemical characterization. Electrodes were soaked in 1 M nitric acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes to further oxidize surface functional groups. For electrohemical measurement, a custom-built liquid cell with 4 mm inner diameter o-ring was used to define the CNF working electrode area while the GCE was placed in a small beaker. DA (5-hydroxytyramine), 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine), and AA were all purchased from Sigma (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and used as purchased. A modified Tris buffer, containing 15 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, 3.25 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM Na2SO4, adjusted to pH 7.4 was used for all electrochemistry experiments.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Microscopy

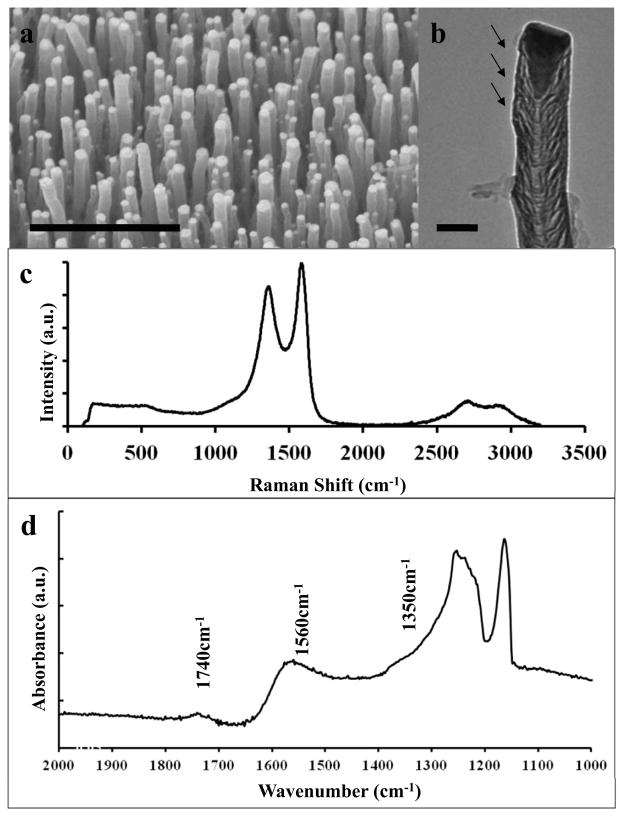

The as-grown CNFs are vertically aligned as seen in the SEM image in Fig. 1a. A bright tear drop-shaped Ni catalyst particle is present at the tip of the CNFs (Fig. 1b) but is easily removed by soaking in nitric acid. The TEM image highlights the bamboo-like structure of CNFs, with crystalline walls bridging the center of the structure and broken walls along the outside of the structure. These outer defect sites have been attributed to good electron transfer and are indicated by the arrows in Fig. 1b. A high abundance of oxidized functional groups present at these defect sites may help attract the positively charged DA and 5-HT while repelling the negatively charged ascorbate ion.

Fig. 1.

a) SEM image of an array of vertically aligned CNFs. Scale bar is 1μm. b) TEM image of an individual nanofiber. Arrows highlight active sites. Scale bar is 0.1 μm. c) Raman spectroscopy of carbon nanofibers. d) FT-IR spectroscopy of carbon nanofibers.

3.2 Spectroscopy

Raman spectra indicate the carbon nanofibers to be of a polycrystalline nature, exhibiting broad D and G-band peaks at 1360 cm−1, indicative of the fiber feature, and 1580 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 1c). The small harmonic 2D peak (~2700 cm−1) indicates that two phonon resonance condition is achieved with the sample and confirms the crystalline nature of the CNFs. However, the intensity and broadness of the D-band relative to the G-band indicate carbon nanofibers with a large amount of defects. The exact origin of these defects is further studied with FT-IR spectroscopy which was used to determine the surface functionalities on the CNF (Fig. 1d). There are three absorbtion peaks present on the IR spectra, at 1740 cm−1, 1560 cm−1, and 1350 cm−1. The peak at 1560 cm−1 can be attributed to the C-C stretching vibratons of C=C bands in the CNF. The 1350 cm−1 peak is convoluted near two symmetry modes from the PTFE film. The frequency of peak position at 1740 cm−1 attributed to C=O stretching vibrations strongly indicates the presence of surface oxygen complexes. A peak position around 1710 cm−1 would indicate the presence of a carbonyl. C=O bonds stretching bands are red shifted in anhydrides lactones, and carboxylic acids (Zhou et al., 2007). The complemetary Raman and FTIR have demosntrated the spectra evidence of carboxylic group as an active component in the CNF sensor.

3.3 Neurotransmitter Detection

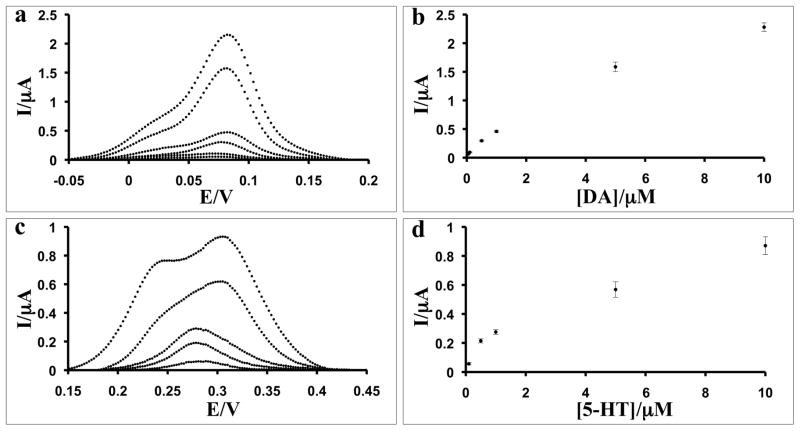

Representative DA and 5-HT differential pulse voltammograms and concentration calibration curves of three sequential measurements for the CNF electrode are shown in Figure 2. The CNF electrode demonstrates superior senstivity towards DA, with detection down to 50 nM in comparison to 100 nM for GCE. The current-to-concentration relationships for the CNF electrode show two linear ranges, from 100 nM to 500 nM, with correlation coefficient of 0.9996, and from 1 μM to 10 μM, with correlation coefficient of 0.9603. Both CNF and GCE electrodes detect down to 100 nM 5-HT. The electrode has linear current-to-concentration relationship for 5-HT in in the range from 1 μM to 10 μM with a correlation coefficient of 0.9970.

Fig. 2.

a) Baseline-corrected DPV scans of CNF electrode with DA concentrations 10 μM, 5 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.1 μM, 0.05 μM; b) Calibration curve for DA; c) Baseline-corrected DPV scans of CNF electrode with 5-HT concentrations 10 μM, 5 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.25 μM, 0.1 μM; and d) Calibration curve for 5-HT

3.4 Mixtures of DA, 5-HT and AA

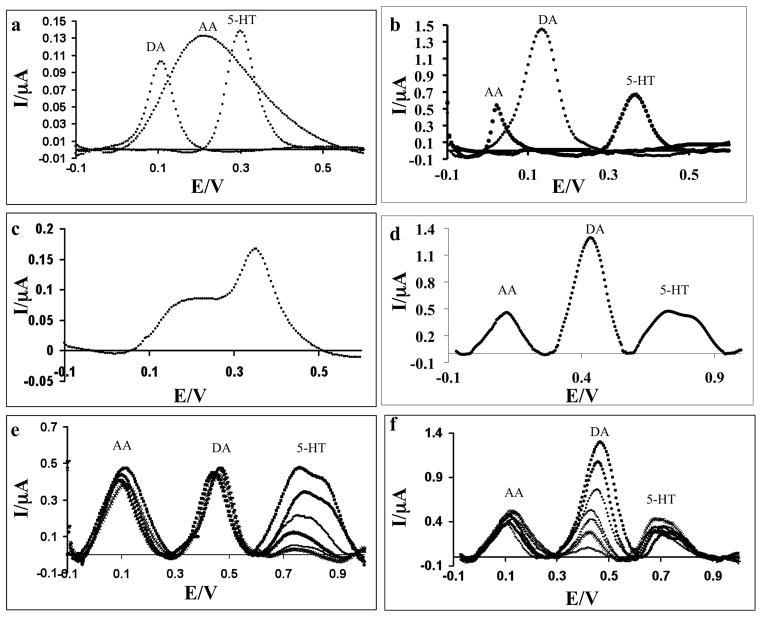

When detected individually, both CNF electrodes and GCE are able to detect DA, 5-HT, and AA using DPV, as shown in the overlay plots in Fig. 3a, b. The AA oxidation potential (Ep) varies based on the electrode material, as shown in the Supplementary Data. The AA oxidation peak is narrow using the CNF electrode and located at a lower potential, Ep(CNF)(AA) = 27 mV, than Ep(CNF)(DA) = 139 mV and Ep(CNF)(5-HT) = 367 mV, which consistent with previous studies using carbon nanotubes (Wang et al. 2003). The AA oxidation by GCE occurs at Ep(GCE)(AA) = 212 mV as a broad peak that overlaps the Ep(GCE)(DA) and Ep(GCE)(5-HT). In addition to peak position and width, the electrode also has a significant effect on oxidation current (ip). At the same concentration of AA and DA, ip(GCE)(DA) is 0.77 times smaller than that ip(GCE)(DA) whereas ip(CNF)(DA) is 2.78 times greater than ip(CNF)(AA). The abundance of COOH groups on the CNFs makes the surface highly electronegative, thereby contributing to electrostatic attraction of dopamine. This manifests as larger ip(CNF)(DA)/ip(CNF)(AA) and ip(CNF)(5-HT)/ip(CNF)(AA) compared to ip(GCE)(DA)/ ip(GCE)(AA) and ip(GCE)(5-HT)/ip(GCE)(AA).

Fig. 3.

a) Baseline-corrected DPV plots of individual detection of 10 μM DA, 1 mM AA, and 10 μM 5-HT with a glassy carbon electrode; b) Background subtracted DPV plots of individual detection of 10 μM DA, 1 mM AA, and 10 μM 5-HT with a carbon nanofiber electrode; c) Baseline-corrected DPV plots of a ternary mixture of 10 uμM DA, 1 mM AA, and 10 μM 5-HT with a glassy carbon electrode; d) Baseline-corrected DPV plots of a ternary mixture of 1 mM AA, 10 μM DA, and 5-HT (10 μM, 5 μM, 2.5 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.25 μM) with a carbon nanofiber electrode; e) Baseline-corrected DPV plots of a ternary mixture of 1 mM AA, 10 μM 5-HT, and DA (10 μM, 5 μM, 2.5 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.25 μM, 0.1 μM) with a carbon nanofiber electrode

In a ternary mixture of AA, DA, and 5-HT, the GCE is unable to distinguish all three species (Fig. 4c) due to overlapping Ep. This makes the GCE an unsuitable electrode for simultaneous detection of DA and 5-HT when AA is present. In contrast, the CNF electrode is capable of distinguishing DA, 5-HT, and AA when they coexist in the same solution. The CNF DPV scans (Fig. 4d) show three distinct peaks, Ep(CNF)(AA)=0.13 V, Ep(CNF)(DA)=0.45 V, and Ep(CNF)(5-HT)=0.70 V. In addition to high selectivity, the CNF electrode retains its sensitivity to DA and 5-HT when exposed to chemical mixtures. The CNF electrode detects DA concentrations ranging from 50 nM-10 μM in the presence of 10 μM 5-HT and 1 mM AA, shown in Fig. 4e, and 5-HT concentrations ranging from 250 nM-10 μM in the presence of 1 μM DA and 1 mM AA, shown in Fig. 4f. When performing multiple scans in the presense of 5-HT, a shoulder is observed on the 5-HT oxidation peak resulting from the oxidation biproducts of 5-HT, consistent with previous studies (Henstridge et al., 2009). Due to its high sensitivity and selectivity of DA and 5-HT in the presense of AA, the CNF electrode is a powerful alternative to CNT- modified GCE and graphene-modified GCE previously attempted in the literature. The CNF electrode fabrication at wafer-scale is straightforward as demonstrated previously (Arumugam et al., 2009) and lends itself to future multiplexing capabilities making it an ideal platform for neurochemical analysis.

4. Conclusions

An electrode based on an array of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers is able to electrochemically discriminate between AA, DA, and 5-HT, which a glassy carbon electrode is unable to do. This performance is attributed to the structure of the nanofibers and the presence of many active sites along the sidewall. The CNF electrode demonstrates excellent stability, selectivity, sensitivity, and spatial and temporal resolution. This is promising for further in vivo and in vitro studies of dopamine, 5-HT, or combinations of the neurotransmitters. The sensitivity can be improved by encapsulating the CNFs in a dielectric, creating a nanoelectrode array (NEA) as we have done in the past for biosensing applications (Arumugam et al., 2009). Our experience indicates fouling with serotonin may be a compromising issue with a dielectric such as silicon dioxide. However, alternatives such as Parylene C (Arumugam et al. 2010) as gap filling matrix material may minimize fouling issues while yielding high sensitivity.

Supplementary Material

Carbon nanofiber and glassy carbon electrodes were used for detection of dopamine and serotonin.

Carbon nanofibers detected mixtures of dopamine and serotonin in the presence of ascorbic acid.

Carbon nanofibers electrodes detected down to 50 nM dopamine and 100 nM serotonin.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by an NIH grant (R01-NS75013) to Mayo Clinic. AP was supported by a NASA URC contract to Texas Southern University (NNx08BA47A) as a visiting Postdoctoral Fellow. The authors would like to thank Patrick Wilhite and Anshul Vyas of Santa Clara University for helpful discussions regarding carbon nanofiber growth.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams RN. Anal Chem. 1976;48:1128A–1138A. doi: 10.1021/ac50008a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwarappan S, Erdem A, Liu C, Li CZ. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:8853–8857. [Google Scholar]

- Alwarappan S, Liu G, Li CZ. Nanomed Nanotech Bio Med. 2010;6:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiou CA, Patel BA, Arundell M, Yeoman MS, Parker KH, O’Hare D. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6990–6998. doi: 10.1021/ac061002q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam PU, Chen H, Siddiqui S, Weinrich JAP, Jejelowo A, Li J, Meyyappan M. Biosens Bioselectron. 2009;24:2818–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam PU, Yu E, Riviere R, Meyyappan M. Chem Phys Lett. 2010;299:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Baur JE, Kristensen EW, May LJ, Wiedemann DJ, Wightman RM. Anal Chem. 1988;60:1268–1272. doi: 10.1021/ac00164a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt GA, Oke AF, Nagy G, Moghaddam B, Adams RN. Brain Research. 1984;290:390–395. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90963-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonon FG, Fombarlet CM, Buda MJ, Pujol JF. Anal Chem. 1981;53:1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Henstridge MC, Wildgoose GG, Compton RG. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:14285–14289. [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Li CM, Cui X, Dong H, Zhou Q. Langmuir. 2007;23:2761–2767. doi: 10.1021/la063024d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Liu Y, Hou H, You T. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Remington G. Am J Psychiat. 1996;153:466–476. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehne JE, Li J, Cassell AM, Chen H, Ye Q, Ng HT, Han J, Meyyappan M. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:676–684. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach PM, Ewing AG, Wilson RL, Wightman RM. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;10:215–227. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Koehne JE, Cassell AM, Chen H, Ng HT, Ye Q, Fan W, Han J, Meyyappan M. Electroanalysis. 2005;17:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Shi Z, Li N, Gu Z, Zhuang Q. Anal Chem. 2001;73:915–920. doi: 10.1021/ac000967l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyyappan M, Delzeit L, Cassell A, Hash D. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2003;12:205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Vu TDB, Chen H, Cassell AM, Andrews RJ, Meyyappan M, Li J. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:1121–1128. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.891169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihel K, Walker QD, Wightman RM. Anal Chem. 1996;68:2084–2089. doi: 10.1021/ac960153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasa S, Blank CL. Anal Chem. 1977;49:354–359. doi: 10.1021/ac50011a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang F, Zhou L, Mahmoud KA, Hrapovic S, Liu Y, Moynihan HA, Glennon JD, Luong JHT. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4089–4098. doi: 10.1021/ac900368m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamford JA, Justice JG. Anal Chem. 1996;68:359A–363A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy BEK, Venton BJ. Analyst. 2007;132:876–884. doi: 10.1039/b705552h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford RA, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 1989;61:98–100. doi: 10.1021/ac00177a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZH, Liang QL, Wang YM, Luo GA. J Electroanal Chem. 2003;540:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, May LJ, Michael AC. Anal Chem. 1988;60:769A–793A. doi: 10.1021/ac00164a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Fei J, Hu S. Anal Biochem. 2003;318:100–106. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zen JM, Chen PJ. Anal Chem. 1997;69:5087–5093. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JH, Sui ZJ, Zhu J, Li P, Chen D, Dai YC, Yuan WK. Carbon. 2007;45:785–796. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.