Abstract

Gene organization on nuclear chromosomes is usually depicted as a linear array, but at least some regions of the genome are localized to specific subnuclear positions in interphase nuclei. Studies in yeast have found that centromeres and telomeres are found around the nuclear periphery, and that tRNA genes are gathered at the nucleolus, along with the ribosomal RNA gene cluster. These 325 loci alone impose significant constraints on the three dimensional organization of chromosomes in the nucleus, and there is mounting experimental evidence that transcription by RNA polymerase II is strongly affected by proximity to these regions. Given these observations, one consideration in understanding nuclear gene regulation might be the degree to which spatial positioning affects at least a subset of gene families.

Keywords: tRNA gene, centromere, telomere, silencing, nucleus, nucleolus, gene organization, nuclear pathways, nuclear architecture

Because of the way information is encoded in DNA, there is a natural tendency to display gene maps as linear chromosomes and to think of distances between genes in linear terms. This form of display is convenient for situations like recombination, where the rate of occurrence is largely consistent with a linear model. However, in interphase nuclei information must be accessed from the DNA in three dimensions. There are two reasons why the arrangement of information logically needs to be considered in space rather than on a line. First, it is widely believed that protein factors regulating gene activity do not scan linearly along chromosomes, but repeatedly bind and release to test for specific contacts. The search for information therefore takes on a three-dimensional rather than one-dimensional quality. Second, chromosomes are not linear entities for any great length in the nucleus but rather are condensed and looped to fit into a relatively small space. This provides ample opportunity for DNA segments that are either quite distant on a single chromosome or on entirely different chromosomes to come into proximity. There is evidence that chromosome positions might be dynamic in interphase nuclei,1,2 suggesting that the relative positions of genes might actually be fluid and responsive to varying conditions.

There is substantial evidence that at least some portions of nuclear genomes are organized into subnuclear locations that reflect the expression of those loci. It has long been known that the tandemly repeated ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene clusters form into dense subnuclear regions termed nucleoli.3 Organization of these regions and ribosome biosynthesis is initiated by transcription of the rRNA genes with RNA polymerase I (pol I). Pol I transcription is also required for the observed inhibition of RNA polymerase II (pol II) transcription in the region.4-6 Other regions where transcription by pol II is inhibited are near the telomeres, silent mating type loci in yeast, and centromeres, all of which have been found associated with the nuclear periphery.7,8 Thus, transcriptional inhibition by pol II is known to occur at regions that have distinctive subnuclear locations, although a causal link has not been established between localization and this transcriptional “silencing”. A logical extension of these observations is to consider whether there is a relationship with the nuclear position of individual gene loci and transcriptional activity. There is support for this view in at least some cases.

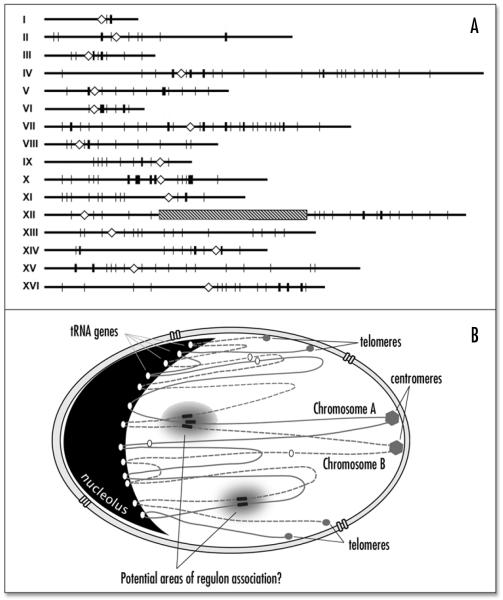

Recently we demonstrated that tRNA genes in yeast are largely found associated with the nucleolus, and that this association is dependent on their being actively transcribed.9 In terms of biosynthetic pathway organization, this arrangement makes perfect sense. It concentrates transcription by RNA polymerase III in one place (along with the 5S rRNA genes) at a location where early pretRNA processing is also concentrated.10 Further, it provides possibilities for coordinate biosynthesis of the two major types of stable RNAs used in translation, tRNA and rRNA. The gathering of the tRNA genes into one sector of the nucleus is counterintuitive, however, because the 275 yeast tRNA genes are scattered throughout the sixteen chromosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Fig. 1A). Clustering these genes in the nucleolus would affect the position of most DNA in the nucleus, giving defined locations for not only the telomeres and centromeres, but also a large number of points in between (Fig. 1B). It should be noted that tRNA gene clustering does not necessarily imply a rigid chromosomal positioning within the nucleus. An individual tRNA locus was shown to be preferentially nucleolar, but to also be found in nucleoplasmic sites 35–50% of the time.9 Thus the positions of individual tRNA genes might be quite malleable, and responsive to forces acting on the surrounding chromatin.

Figure 1.

Gene position in one dimension and three dimensions. (A) Linear genome map of the sixteen chromosomes (I – XVI) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The tandemly repeated cluster of ribosomal RNA genes contained in the nucleolus are shown as a single striped bar in Chromosome XII. Centromeres are shown as diamonds, and the positions of the 275 tRNA genes are indicated by vertical lines. (B) Hypothesis for the nuclear organization of genes and non-transcribed chromosomal regions, showing only two hypothetical yeast chromosomes. Positioning of the telomeres and centromeres at the nuclear periphery is documented, as is the preferential localization of transcribed tRNA genes at the nucleolus. Hypothetical functional groupings of additional transcription units are indicated by shaded areas.

There is little information as to how tRNA gene localization is accomplished, but the requirement for transcription of the tRNA genes suggests an interaction of the transcription machinery with some mobile structural component of the nucleus. What about other genes, those in regulons that are transcribed by RNA polymerase II? It is possible to envision a scenario where some coregulated genes are brought together in a transcription-dependent fashion (Fig. 1B). In bacteria, coregulated genes are often cotranscribed linearly as operons, but there is also substantial evidence for spatial clustering of genome regions and the regulators that control their expression.11 Several specific examples of such spatially regulated genes in mammals exist,12-14 but a systematic analysis of gene and regulon positions relative to their activation has not yet been accomplished.

It is interesting to note that transcription by pol II is antagonized in the vicinity of active tRNA genes,15-17 and that this transcriptional silencing is dependent on nucleolar organization rather than mechanisms that effect other forms of silencing at telomeres, silent mating type loci, and rRNA gene clusters (Wang L, Good P, Haeusler R, Engelke D, unpublished observations). Thus, tRNA genes provide another example of silencing of pol II transcription in proximity to a localized DNA element, although the details of the mechanisms differ. A striking difference between tRNA genes and the other silencing elements is that the tRNA genes are scattered throughout the chromosomes in large numbers, suggesting that these element affect a substantial portion of the genome.

Pol II promoters are under represented within 500 base pairs of a tRNA gene, with the notable exception of Ty retrotransposons, which are preferentially adjacent to tRNA genes.18-20 These retrotransposons have clearly adapted to this environment and must derive some selective advantage from this arrangement. They can be transcriptionally activated in response to mating type signals, but the activation of at least the Ty3 class has been shown to be conditionally affected by the transcriptional state of their neighboring tRNA genes.15,16 In this context it is interesting that the one class of Ty elements not found associated with tRNA genes, Ty5, integrates preferentially at other transcriptionally silenced regions, telomeres and silent mating loci.21,22 Combined, these observations suggest a model of coordination between pol II transcription and spatial positioning.

Does spatial organization affect only loci near tRNA genes, telomeres, and centromeres, or are most promoters clustered in functional groupings? It is hard to imagine a level of choreography that would provide an exact, predetermined position for each gene depending on its transcriptional state, especially since shifting regulatory signals would continuously create new functional groupings and require massive rearrangements. Nonetheless, some intermediate level of three-dimensional organization is likely to exist, and studies of spatial effects could lead to new insights into the mechanisms of nuclear information retrieval.

References

- 1.Heun P, Laroche T, Shimada K, Furrer P, Gasser SM. Chromosome dynamics in the yeast interphase nucleus. Science. 2001;294:2181–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1065366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vazquez J, Belmont AS, Sedat JW. Multiple regimes of constrained chromosome motion are regulated in the interphase Drosophila nucleus. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1227–39. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pederson T. The plurifunctional nucleolus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3871–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JS, Boeke JD. An unusual form of transcriptional silencing in yeast ribosomal DNA. Genes Dev. 1997;11:241–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryk M, Banerjee M, Murphy M, Knudsen KE, Garfinkel DJ, Curcio MJ. Transcriptional silencing of Ty1 elements in the RDN1 locus of yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:255–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cioci F, Vu L, Eliason K, Oakes M, Siddiqi IN, Nomura M. Silencing in yeast rDNA chromatin: Reciprocal relationship in gene expression between RNA polymerase I and II. Mol Cell. 2003;12:135–45. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hediger F, Gasser SM. Nuclear organization and silencing: Putting things in their place. Nat Cell Bio. 4:E53–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb0302-e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter J, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. Nuclear organization and gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:372–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson M, Haeusler RA, Good PD, Engelke DR. Nucleolar clustering of dispersed tRNA genes. Science. 2003;302:1399–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1089814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertrand E, Houser-Scott F, Kendall A, Singer RH, Engelke DR. Nucleolar localization of early tRNA processing. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2463–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAdams HH, Shapiro L. A bacterial cell-cycle regulatory network operating in time and space. Science. 2003;301:1874–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1087694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown KE, Baxter J, Graf D, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. Dynamic repositioning of genes in the nucleus of lymphocytes preparing for cell division. Mol Cell. 1999;3:207–17. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpi EV, Chevret E, Jones T, Vatcheva R, Williamson J, Beck S, et al. Large-scale chromatin organization of the major histocompatibility complex and other regions of human chromosome 6 and its response to interferon in interphase nuclei. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1565–76. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.9.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosak ST, Skok JA, Medina KL, Riblet R, Le Beau MM, Fisher AG, et al. Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science. 2002;296:158–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1068768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinsey PT, Sandmeyer SB. Adjacent pol II and pol III promoters: Transcription of the yeast retrotransposon Ty3 and a target tRNA gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1317–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hull M, Erickson J, Johnston M, Engelke DR. tRNA genes as transcriptional repressor elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3244–52. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendall A, Hull MW, Bertrand E, Good PD, Singer RH, Engelke DR. A CBF5 mutation that disrupts nucleolar localization of early tRNA biosynthesis in yeast also suppresses tRNA gene-mediated transcriptional silencing. PNAS. 2000;97:13108–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240454997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boeke JD, Sandmeyer SB. In: The molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Broach J, Jones E, Pringle J, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1991. pp. 193–261. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolton EC, Boeke JD. Transcriptional interactions between yeast tRNA genes, flanking genes and Ty elements: A genomic point of view. Genome Res. 13:254–63. doi: 10.1101/gr.612203. 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JM, Vanguri S, Boeke JD, Gabriel A, Voytas DF. Transposable elements and genome organization: A comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 1998;8:464–78. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou S, Ke N, Kim JM, Voytas DF. The Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5 integrates preferentially into regions of silent chromatin at the telomeres and mating loci. Genes Dev. 1996;10:634–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou S, Voytas DF. Silent chromatin determines target preference of the Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5. PNAS. 1997;94:7412–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]