Abstract

Background

Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection is typically associated with lymphadenitis in immune competent children, and disseminated disease in children with immune deficiencies. Isolated pulmonary NTM disease is seen in cystic fibrosis, and is increasingly recognized in immunocompetent elderly women, where it is associated with an increased incidence of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) mutations. Thoracic NTM infection has been reported rarely in otherwise healthy children. We aimed to determine whether otherwise healthy children with pulmonary NTM disease had immunologic abnormalities or CFTR mutations.

Study Design

Clinical presentations of five otherwise healthy children with pulmonary NTM were reviewed. Immunologic studies were performed including a complete blood cell count (CBC), flow cytometric lymphocyte phenotyping and IFN-gamma receptor expression, in vitro cytokine stimulation, and serum immunoglobulin levels. Mutational analysis was performed for CFTR.

Results

The children ranged in age from 12 months to 2.5 years at diagnosis. Four presented with new onset wheezing or stridor failing bronchodilator therapy. One child was asymptomatic. Endobronchial lesions and/or hilar lymph nodes causing bronchial obstruction were identified in all patients. Mycobacterium avium complex was cultured from four patients, and M. abscessus from one patient. All patients were successfully treated with anti-mycobacterial therapy with or without surgery. No definitive immunologic abnormalities were identified. No clinically significant mutations were found in CFTR.

Conclusions

Pulmonary NTM infection should be considered in otherwise healthy young children presenting with refractory stridor or wheezing with endobronchial lesions or hilar lymphadenopathy. It does not appear to be associated with recognized underlying immune deficiency or CFTR mutations.

Keywords: nontuberculous mycobacteria, intrathoracic infection, hilar lymphadenopathy, endobronchial granuloma

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous organisms of water and soil that in immunocompetent children most commonly cause cervical lymphadenitis. These children typically present in the first five years of life and presumably become infected after the organisms invade small oral abrasions after ingestion1–4. Surgical resection is curative, and infection typically does not recur. NTM infection outside of cervical lymph nodes is much less common in children, but may occur as localized disease in immunocompetent children after direct inoculation, such as skin infection with Mycobacterium marinum after an aquatic exposure. Disseminated NTM disease occurs in children with immune deficiencies such as HIV or abnormalities in the IL-12/IFN-g pathway. Isolated pulmonary disease is associated with cystic fibrosis (CF)5–8.

There have been several reports in recent years of isolated thoracic mycobacterial disease in apparently immunocompetent children without evidence of CF9–13. Disease has been limited to endobronchial lesions or hilar adenopathy, as opposed to pulmonary NTM disease in immunocompetent adults, which tends to be parenchymal. Adult lung disease due to NTM occurs in older smokers or older Caucasian women often associated with CFTR mutations14,15. Immune competence of these children has been presumed due to a lack of a previous unusual or recurrent infection, and as a result of limited immunologic evaluation. CFTR mutation analysis has not been reported. To try and clarify whether isolated endobronchial NTM in children is due to any of the described predisposing factors for pulmonary or disseminated NTM, we extensively evaluated five otherwise healthy children with intrathoracic NTM disease immunologically and by CFTR sequencing.

Subjects

All children were enrolled on an Institutional review board (IRB) approved natural history of mycobacterial infection protocol at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Case Histories (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient | Age | Sex | Symptoms at Presentation | TST | Imaging/Bronchoscopy Findings | Isolate | Length of Disease-Free Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.5 y | F | Wheezing unresponsive to bronchodilators | 5mm | CXR: left hyperinflation Bronchoscopy: left main stem granuloma | MAC | 4.5 y |

| 2 | 14 m | F | Labored breathing unresponsive to bronchodilators | 9mm | Bronchoscopy: Bilateral masses in main stem bronchi | MAC | 8 y |

| 3 | 2 y | M | Wheezing/stridor unresponsive to bronchodilators | 0mm | Chest CT: soft tissue mass of right bronchus | M. abscessus | 6 y |

| 4 | 12 m | M | None | 20mm | CXR: right perihilar nodes; Chest CT: right perihilar nodes causing right middle lobe hyperinflation | MAC | 2 y |

| 5 | 22 m | M | Stridor, Failure to thrive, vomiting | 0mm | CXR: hilar adenopathy CT: multiple bilateral hilar nodes with central necrosis | MAC | 3 y |

Patient 1

A 2.5 year old girl presented with new onset wheezing unresponsive to bronchodilator therapy. A chest X-ray (CXR) showed mild left hyperinflation, but chest computed tomography (CT) showed no masses or infiltrates. Bronchoscopic evaluation found a mass in the left main stem bronchus, which was endoscopically resected; pathology showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, and the culture was positive for Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). Repeat bronchoscopy 2 months later showed recurrence of the lesion, although cultures were negative. Treatment was initiated with azithromycin and rifampin daily. Three months later, wheezing recurred, and repeat bronchoscopy found recurrence at the site of the previous resection. Cultures remained negative, but therapy was broadened to clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifampin, with moxifloxacin substituted for ciprofloxacin after 4 months. The granuloma recurred requiring resection a third time, but cultures were negative. Therapy was discontinued after 3.5 years and the chest CT scan has remained stable. Her medical history was otherwise significant only for vesicoureteral reflux, for which she received sulfonamide prophylaxis. At 4.5 year follow-up evaluation from initial presentation, there were no recurrent infections.

Patient 2

A 14 month old girl presented with labored breathing and coughing unresponsive to steroids and bronchodilator therapy. Bronchoscopy at 16 months of age found bilateral masses in the main stem bronchi, right greater than left. Biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and her respiratory symptoms improved immediately after removal of tissue. Tuberculin skin test (TST) showed 9 mm of induration and isoniazid and rifampin were started for presumptive tuberculosis. After culture was positive for MAC, these medications were discontinued, and azithromycin was initiated. Azithromycin was discontinued after a year with return of respiratory distress symptoms a few months later. Repeat bronchoscopic removal brought about relief of symptoms again and the patient was placed back on azithromycin. Therapy with azithromycin was continued for 8 years without recurrence of symptoms or chest CT findings. Her medical history is otherwise significant only for recurrent otitis media requiring tympanostomy tubes twice and an adenotonsillectomy. The azithromycin has been discontinued for a year now and she has remained free of symptoms. She has had no other recurrent or unusual infections, nor family history of immunodeficiency. Growth and development have been normal.

Patient 3

A 2 year old boy presented with new onset wheezing followed by stridor unresponsive to bronchodilator therapy. Airway fluoroscopy showed a soft tissue opacity obscuring the right bronchus. Chest CT and bronchoscopy confirmed obstruction of the right mainstem bronchus by a mass. Surgical resection of the right mainstem bronchus and right middle and lower lobes was performed; pathology showed granulomatous inflammation of the bronchus and multiple lymph nodes. Stains were positive for acid-fast bacilli and culture grew Mycobacterium abscessus. The lung parenchyma had foci of lymphoid aggregates. Therapy was initiated with ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin. Cultures from bronchoscopy repeated 3, 6 and 12 months after surgical resection were still positive for M. abscessus. Cultures after 18 months of therapy were negative, and at age 6 years no further unusual or recurrent infections had occurred. In addition to an immune evaluation including lymphocyte phenotyping and quantitative immunoglobulins (Table 2), FISH for DiGeorge syndrome was negative.

Table 2.

Laboratory evaluation. Unless noted, all values within normal range for age.

| Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Age at Evaluation | 6 yrs | 7 yrs | 6 yrs | 1.5 yrs | 2.5 yrs |

| ANC | 1100 | 1024 | 2065 | 1493 | 2287 |

| ALC | 4660 | 1642 | 2411 | 5026 | 4038 |

| CD3+/CD4+ (abs cells/uL) | 1070 | 906 | 1295 | 2433 | 2039 |

| CD3+/CD8+ (cells/uL) | 661 | 301 | 692 | 1005 | 840 |

| CD19+ B cells (cells/uL) | 938 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CD20+B cells (cells/uL) | ND | 193 | 596 | 1101 | 783 |

| NK Cell (cells/uL) | 198 | 193 | 596 | 342 | 824 |

| IgA mg/dL | 46 | 173 | 43 | ND | 74 |

| IgG mg/dL | 698 | 1010 | 5441 | ND | 533 |

| IgM mg/dL | 89 | 113 | 90 | ND | 69 |

| IFN-GR% | ND | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| HIV 1/2 ELISA | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CFTR mutations | None2 | None3 | None | None | None |

Normal range for age 633–1280,

(TG)12-5T/(TG)12-7T normal variant,

(TG)11-5T/(TG)-7T normal variant

ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ALC: absolute lymphocyte count

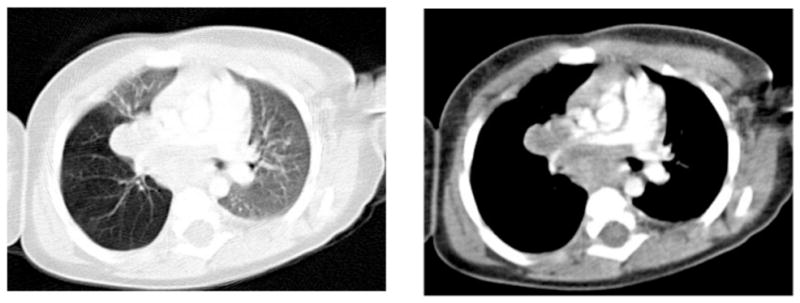

Patient 4

A 12 month old boy had a TST placed at a routine well child visit that was reactive with an induration that measured 20mm. He was asymptomatic, and had no tuberculosis risk factors. CXR showed right perihilar nodes obstructing the right bronchus, and chest CT confirmed a large right hilar and subcarinal mass obstructing the bronchus intermedius with resultant air trapping of the right lung (Figure 1). Anti-tuberculous therapy was started with isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide as well as a prednisone to reduce the bronchial obstruction. Cultures from bronchoscopy were positive for MAC and therapy was changed to rifampin, clarithromycin and ethambutol, and the prednisone tapered. He was treated for one year with normalization of CXR. Past medical history was significant only for prematurity, at 34 weeks gestation, and respiratory distress at birth requiring 2 days of respiratory support. At 2 years follow-up there were no recurrent or unusual infections. Family history was noncontributory.

Figure 1.

Chest CT of patient 4 at diagnosis showing hilar lymphadenopathy and air trapping of the right lung.

Patient 5

A 22 month old boy presented with a four-week history of vomiting, lethargy, failure to thrive, and stridor initially diagnosed as croup. CXR showed hilar lymphadenopathy, and chest CT scan confirmed multiple enlarged bilateral hilar lymph nodes with central necrosis. Thoracoscopic lymph node biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation with central necrosis; stains for acid-fast bacilli were positive. TST was nonreactive and PCR for tuberculosis was negative. Therapy was initiated for NTM infection with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Culture subsequently grew MAC. Sweat chloride testing was normal. At one year follow-up, he had returned to his growth curve and normal energy level. Chest CT showed resolution of the infection with calcification of hilar nodes. At 3 years of follow-up, he has not had any other unusual infections or recurrent infections and family history has been noncontributory.

Methods

Immunologic evaluation included complete blood count and differential, antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), lymphocyte phenotyping by flow cytometry, detection of interferon-gamma (IFN-g) receptor 1 by flow cytometry, quantitative immunoglobulins, and cytokine analysis. Immunoglobulin evaluation was not performed for patient 4 and IFN-g receptor detection was not performed for patient 1. Laboratory studies were performed when the patients had recovered from the acute illnesses. Cytokine analysis was performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for Interleukin (IL)-1Beta, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, GM-CSF, and IFN-g by multiplex cytokine analysis (Pro-Inflammatory Tissue Culture 9-Plex, MesoScale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) after 48 hour stimulation with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), PHA+ IL-12, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS + IFN-g using a SECTOR™ Imager 6000 reader (MesoScale Discovery) according to the manufacturer instructions. Mutational analysis of CFTR was performed by Ambry™ for patient 1, 2, and 3 and by Genzyme™ for patients 4 and 5.

Results

Immunologic evaluation was normal for all patients with the exception of a mildly low total serum IgG for patient 3 of 544 mg/dL (normal for his age of 633–1280) (Table 2). The other serum immunoglobulins for this patient as well as his number of B cells were normal, and his IgG was normal at age 10 years (715mg/dL) as were the specific antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccination. IFN-g receptor was present for all tested patients, and upon cytokine analysis, the IL-12/IFN-g pathway appeared intact for all patients. TNF-alpha production was increased after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) plus interferon-gamma stimulation compared to LPS alone for all subjects, demonstrating normal signaling through the IFN-gamma receptor. Interferon-gamma production was increased after phytohemagglutinin (PHA) plus IL-12 compared to PHA alone, demonstrating normal signaling through the IL-12 receptor pathway. In addition, all other cytokine responses were appropriate.

No recognized disease causing mutations were detected upon sequencing of CFTR. Patient 1 had a (TG)12-5T/(TG)12-7T normal variant, and patient 2 had a (TG)11-5T/(TG)-7T normal variant detected. Sweat test examinations were performed for patients 1, 2, and 5, and were normal.

Discussion

NTM are ubiquitous in the environment, but are an uncommon etiology of infection. In immunocompetent children, NTM are most commonly associated with cervical lymphadenitis, typically between the ages of one and five years. The portal of entry for the mycobacteria is hypothesized to be the oropharynx through ingestion of contaminated soil and water1,2. These infections present in a subacute manner, and full excision is usually curative without a need for additional antimicrobials. When excision is not performed or is incomplete, anti-mycobacterial medications including clarithromycin, azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin, either in combination or individually are usually effective3,16. Resolution may even occur without antimicrobial therapy. Disseminated NTM infection, such as osteomyelitis, hepatosplenic disease, and multiple site cutaneous disease, is usually associated with immune deficiencies including HIV or abnormalities of the IL-12/IFN-gamma pathway, such as IFN-g receptor defects or NF kappa B essential modulator operon (NEMO) defects5,7. For these children, combination anti-mycobacterials are used for prolonged courses, and adjunctive immunomodulator therapy, such as IFN-gamma or IFN-alpha, may be helpful in selected cases. In these severe immunodeficiencies, recurrence of mycobacterial disease is common, as are other infections (e.g. salmonellosis with IFN-g receptor defects, and recurrent bacterial and viral illness in children with NEMO mutations).

The patients described here are similar to those in the literature with disease localized to endobronchial lesions or mediastinal lymph nodes9–13, 17. Nolt et al reported 43 children with thoracic NTM disease; the median age was 24 months, the same age group we report here12. Although this appears to be the predominant age group, the disease may occur in older children or adults. There is a case with thoracic presentation and imaging findings similar to the children reported here in an immunocompetent 29 year old woman17. The presentations in the majority of reported cases are similar to those in our series, with cough and wheezing predominating; in the review of 43 patients, only 23 had associated fever12. The majority of reported patients have been treated with prolonged combination antimycobacterial agents after biopsy diagnosis with or without surgical resection; some have been treated with limited antibiotics after surgical resection9–12. Recurrence of NTM disease was uncommon. Extensive immunologic evaluation has not been reported for the majority of cases, but immunocompetence was inferred by the lack of associated infections. In one case, evidence of an intact IL-12/IFN-g pathway was provided, similar to the studies in our patients11.

NTM disease in children is distinct from the isolated pulmonary NTM disease increasingly reported in adults14. The majority of isolated pulmonary MAC disease in previously healthy adults occurs in post-menopausal Caucasian women without any known immune defect. However, those women do have an increased incidence of CFTR mutations, ranging form 36–50%14,15. Unlike the children we report, chest CT in these older individuals typically shows parenchymal disease with nodular infiltrates and bronchiectasis. Prolonged courses of multiple antibiotics are typically administered for at least one year after sputum culture conversion. In children and adolescents, NTM can be significant pulmonary pathogens in individuals with cystic fibrosis6,7. Unlike previous reports of otherwise healthy children with intrathoracic NTM disease, we performed mutation analysis of CFTR, and no clinically significant mutations were detected.

NTM can cause intrathoracic disease in immunocompetent children without CFTR mutations. As opposed to the disease seen in immunocompetent adults, intrathoracic NTM disease in children appears to spare lung parenchyma. There is typically one area of abnormality, usually involving a lymph node, and parenchymal lung disease is mostly from compression of larger airways by this infected endobronchial lesion or node. Intrathoracic NTM lymphadenitis appears to be very similar to NTM cervical lymphadenitis seen in immunocompetent children in terms of age of onset, localization to a limited number of lymph nodes, and the lack of recurrence of disease. Just as cervical lymphadenitis is presumed to occur as a result of local exposure following ingestion, intrathoracic disease may be hypothesized to occur after inhalation of contaminated materials. Similar to our findings, immunologic abnormalities have not been identified in children with isolated cervical lymphadenitis, with evaluations including that of the IL-12/IFN-g pathway4. Although a more subtle immune abnormality may associated with isolated intrathoracic NTM lymphadenitis or endobronchial disease, just as it may be with isolated NTM cervical adenitis, it does not appear to be one of those already recognized. Optimal initial and subsequent drug therapy for these children is undefined but combination antimycobacterial therapy is prudent and effective.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contracts N01-CO-12400 and HHSN261200800001E as well as by the intramural program of NIAID.

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contracts N01-CO-12400 and HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This research was supported [in part] by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Abbreviations

- NTM

Nontuberculous mycobacteria

- IL

interleukin

- IFN

interferon

- CFTR

Cystic Fibrosis transmembrane regulator

- CF

Cystic fibrosis

- CXR

chest X-ray

- CT

computed tomography

- MAC

Mycobacterium avium complex

- TST

tuberculin skin test

References

- 1.Albright JT, Pransky SM. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections of the head and neck. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2003;50:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesney PJ. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. Pediatrics in Review. 2002;23:300–309. doi: 10.1542/pir.23-9-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazra R, Robson CD, Perez-Atayde AR, Husson RN. Lymphadenitis due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in children: presentation and response to therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1999;28:123–9. doi: 10.1086/515091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serour F, Mizrahi A, Somekh E, et al. Analysis of the host Interleukin-12/interferon-gamma pathway in children with non-tuberculous mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:835–841. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doffinger R, Patel SY, Kumararatne DS. Host genetic factors and mycobacterial infections: lessons from single gene disorders affecting innate and adaptive immunity. Microbes and Infection. 2006;8:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esther CR, Henry MM, Molina PL, Leigh MW. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2005;40:39–44. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivier KN NTM in CF Study Group. The natural history of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis. Paediatric Respiratory Review. 2004;5(Supplement A):S213–6. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0542(04)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remus N, Reichenbach J, Picard C, et al. Impaired interferon gamma-mediated immunity and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in childhood. Pediatric Research. 2001;50:8–13. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergie JE, Milligan TW, Henderson BM, Stafford WW. Intrathoracic Mycobacterium avium complex infection in immunocompetent children: case report and review of the literature. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997;24:250–3. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson LO, Berg-Kelly K. Temporary intrathoracic adenopathy in children- a response to infection caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Acta Paediatrica. 1996;85:508–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levelink B, deVries E, vanDissel JT, van Dongen JJM. Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent child. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2004;23:892. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000137585.07272.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolt D, Michaels MG, Wald ER. Intrathoracic disease from nontuberculous mycobacteria in children: two cases and a review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e434–439. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osorio A, Kessler RM, Guruprasad H, Isaacson G. Isolated intrathoracic presentation of Mycobacterium avium complex in an immunocompetent child. Pediatric Radiology. 2001;31:848–851. doi: 10.1007/s002470100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler SJ, French J, Screaton NJ, Foweraker J, Condliffe A, Haworth CS, Exley AR, Bilton D. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in bronchiectasis: prevalence and patient characteristics. European Respiratory Journal. 2006;28:1204–10. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00149805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziedalski TM, Kao PN, Henig NR, Jacobs SS, Ruoss SJ. Prospective analysis of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutations in adults with bronchiectasis or pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Chest. 2006;130:995–1002. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulter JB, Lloyd DA, Jones M, Cooper JC, McCormick MS, Clarke RW, Tawil MI. Nontuberculous mycobacterial adenitis: effectiveness of chemotherapy following incomplete excision. Acta Pediatrica. 2006;95:182–8. doi: 10.1080/08035250500331056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greinert U, Rusch-Gerdes S, Vollmer E, Schlaak M. Extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy in an adult immunocompetent woman caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Chest. 1999;116:1814–1816. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]