Abstract

Objective

Recent work suggests that delivery of continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation is an acceptable layperson resuscitation strategy, although little is known about layperson preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation. We hypothesized that continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation education would lead to greater trainee confidence and would encourage wider dissemination of cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills compared to standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation training (30 compressions: two breaths).

Design

Prospective, multicenter cohort study.

Setting

Three academic medical center inpatient wards.

Subjects

Adult family members or friends (≥18 yrs old) of inpatients admitted with cardiac-related diagnoses.

Interventions

In a multicenter randomized trial, family members of hospitalized patients were trained via the educational method of video self-instruction. Subjects were randomized to continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation or standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation educational modes.

Measurements

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation performance data were collected using a cardiopulmonary resuscitation skill-reporting manikin. Trainee perspectives and secondary training rates were assessed through mixed qualitative and quantitative survey instruments.

Main Results

Chest compression performance was similar in both groups. The trainees in the continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation group were significantly more likely to express a desire to share their training kit with others (152 of 207 [73%] vs. 133 of 199 [67%], p = .03). Subjects were contacted 1 month after initial enrollment to assess actual sharing, or “secondary training.” Kits were shared with 2.0 ± 3.4 additional family members in the continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation group vs. 1.2 ± 2.2 in the standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation group (p = .03). As a secondary result, trainees in the continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation group were more likely to rate themselves “very comfortable” with the idea of using cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills in actual events than the standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation trainees (71 of 207 [34%] vs. 57 of 199 [28%], p = .08).

Conclusions

Continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation education resulted in a statistically significant increase in secondary training. This work suggests that implementation of video self-instruction training programs using continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation may confer broader dissemination of life-saving skills and may promote rescuer comfort with newly acquired cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01260441.

Keywords: cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, education, hospital care, quality of care, sudden death

Prompt delivery of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a crucial determinant of survival for many victims of sudden cardiac arrest, yet bystander CPR is provided in less than one third of witnessed sudden cardiac arrest events (1, 2). A number of barriers to bystander CPR training and delivery have been identified, including fear of incorrectly performing the complex maneuvers inherent in CPR, and apprehension to deliver mouth-to-mouth ventilation (3–7).

Recent investigations have suggested that continuous chest compression CPR (CC-CPR), without the provision of rescue breaths, is an acceptable alternative to standard CPR (30 compressions: two ventilations) for lay bystanders providing immediate care (8 –11). An observational study in Japan documented that patients receiving CC-CPR exhibited more favorable neurologic outcomes than those who received standard CPR (12). Other investigations have found that outcomes are indistinguishable when either CC-CPR or standard CPR strategies are employed (13–17). Despite these findings, little evidence exists to address whether CC-CPR or standard CPR represents the preferable strategy for educational dissemination to the lay public, and to determine whether CC-CPR reduces purported barriers to CPR training or delivery.

Since the large majority of arrest events occur in the home environment, studies have suggested that providing CPR training to family members of hospitalized cardiac patients or other high-risk individuals may serve as a useful approach to address an environment in which bystander CPR is frequently not provided (18 –22). Utilizing an existing in-hospital program to train family members via video self-instruction (VSI) CPR kits, we assessed the motivation and skills of those who learned two different modes of CPR (CC-CPR and standard CPR) through an enrollment-blinded randomized controlled trial. We hypothesized that subjects exposed to CC-CPR would express more confidence in resuscitation skills and would more frequently share the VSI learning tool with others (i.e., “secondary training” in CPR skills).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and Setting

Our multisite randomized educational trial was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and was registered with the national clinical trials registry (ClinicalTrials.gov, National Institutes of Health). Enrollment using standard written consent mechanisms was conducted at three hospitals within the University of Pennsylvania Health System: the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (a 700-bed tertiary care academic medical center), Penn Presbyterian Medical Center (a 300-bed tertiary care hospital), and Pennsylvania Hospital (a 500-bed community hospital). Adult family members of hospitalized patients on cardiology service line wards were eligible for participation, with active enrollment conducted between May, 2009 and May, 2010.

CPR Training Tool

We employed a commercially available and validated CPR VSI program (CPR Anytime Family and Friends, American Heart Association, Dallas, TX, and Laerdal Medical, Stavanger, Norway). This VSI program is packaged in a kit containing an inflatable head/ torso manikin and instructional DVD of 25-min duration. To prepare a CC-CPR instructional mode, the original video program teaching standard CPR (30:2) was modified by editing out the ventilation instructions, but in both modes the actor, lighting, sound, and general scripting were kept the same. To ensure program clarity, the CC-CPR DVD was pilot tested with a cohort of 20 subjects. This pilot work, and our initial feasibility trial of using the hospital-based VSI strategy, has been described previously (18).

Study Design

This study was structured as a randomized controlled trial testing two modes of CPR education dissemination, partially blinded at the level of the subject and enroller before the initiation of training. That is, before subject consent and prestudy survey completion, enrolling study staff members and potential subjects were unaware of the training mode to which the subject would be randomized. To achieve this, a block-randomization approach was employed, in which training kit DVDs were randomly bundled into groups of 20 (ten DVDs of each mode), and the DVDs themselves were unmarked and packaged in nondescript sleeves.

CPR training was offered to family members of hospitalized patients in the cardiology service line/telemetry wards of each study hospital. Specific subject inclusion criteria were: 1) the family member to be enrolled was physically present with the patient; 2) the patient had an admission diagnosis related to coronary artery disease or multiple established cardiovascular risk factors; 3) the patient was in stable condition as determined by primary nursing staff; and 4) the family member to be enrolled had sufficient English competency. If the family member met these criteria, the potential subject was asked a short set of additional screening questions to determine study eligibility and was excluded if he or she: 1) had received CPR training in the past 2 yrs; 2) was under 18 yrs of age; or 3) felt unwell or unable to perform moderate physical activity at the time of enrollment. Individuals satisfying enrollment criteria underwent a written informed consent process, and then completed a pretraining survey designed to gather general demographic information. If the family member declined participation, the potential subject was asked to provide their demographic information and reason for nonparticipation to assess barriers to training. Results from this secondary data collection will be discussed more fully in a future publication.

Each subject was given a VSI kit, containing either the CC-CPR or standard CPR DVD program. Research staff refrained from providing educational input during the training, which took place in the family waiting room or staff conference room within or near the hospital ward. Investigative staff then administered a 2-min objective skills assessment of CPR performance, recorded on a CPR-recording manikin (Skillreporter ResusciAnne, Laerdal Medical) and also via video recording. Finally, the subjects completed a brief post-training survey, designed to assess comfort level of learning CPR through this process and likelihood of both performing CPR and sharing the VSI kit with others. No financial compensation was provided for this portion of the study.

To assess whether subjects shared the kit with additional family members and friends (“secondary training,” as described in prior studies of VSI CPR initiatives [23]), subjects were surveyed via telephone at 1 month following training. Subjects were queried regarding whether they shared the VSI kit, and if so, with how many other individuals. From this, a “multiplier effect” of secondary training was calculated by taking the total number of people trained per kit and dividing that number by the total kits distributed.

Statistical Approach and Analysis

All data were compiled using a standard spreadsheet application (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and analyzed using a statistical software package (STATA 10.0, Statacorp, College Station, TX). Resuscitation performance data were analyzed using a Student’s t test; the Likert-scaled survey data were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis testing. Demographic data were examined using a chi-square test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. The secondary training was analyzed for statistical significance using a Student’s t test. Open-ended responses were manually coded and grouped for common themes for qualitative presentation. Study sample size was based on a power calculation using the outcome measure of CPR quality differences between the two groups, with an α = 0.05 and 80% power (1-β = 0.8). Enrollment was stopped once we reached the target sample size.

RESULTS

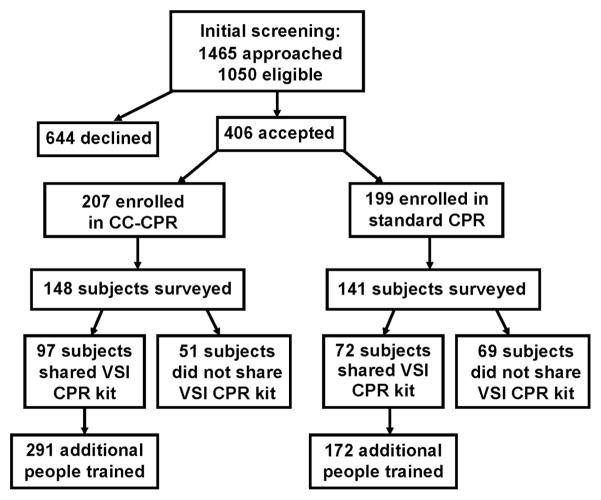

A total of 1,465 individuals were initially approached to participate in the study between May 2009 and May 2010, of which 1,050 met eligibility criteria. From this target group, 406 individuals enrolled in the study, representing a 39% enrollment rate (Fig. 1). Among the 406 subjects, 207 received CC-CPR training and 199 underwent standard CPR training. Characteristics and demographics of the enrolled population are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 53 ± 14 yrs, and 292 of 406 (72%) were female. The majority of enrollees, 325 of 406 (80%), reported being the spouse or immediate family member of the “at-risk” patient, and 342 of 406 (84%) had no previous CPR training or had only received such training 10 or more years before enrollment. No significant differences were found between the two randomization groups with respect to age, gender, educational level, or time from prior CPR training. No subjects experienced adverse effects (e.g., fatigue or shortness of breath) from the training.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of screening and enrollment. All screening and enrollment was performed in the ward settings of the three study hospitals. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CC-CPR, continuous chest compression CPR; VSI, video self-instruction.

Table 1.

Demographics of enrolled subjects

| Demographics | Screened but Declined n = 644 | Continuous Chest Compression CPR (%)n = 207 | Standard CPR (%)n = 199 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49 ± 20 | 52 ± 14 | 53 ± 14 | .81 |

| Female gender | 451 (70) | 147 (71) | 145 (73) | .68 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 456 (71) | 132 (65) | 143 (72) | .05 |

| Black | 111 (17) | 61 (29) | 51 (26) | |

| Other | 27 (4) | 11 (5) | 5 (2) | |

| No response | 50 (8) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Relationship to patient | ||||

| Spouse | 213 (33) | 81 (39) | 81 (40) | .38 |

| Immediate family | 243 (38) | 84 (40) | 79 (40) | |

| Other | 108 (17) | 39 (19) | 37 (19) | |

| No response | 80 (12) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Highest education | ||||

| High school or less | 168 (26) | 66 (32) | 63 (32) | .87 |

| Some college | 121 (19) | 60 (29) | 58 (29) | |

| College | 167 (26) | 49 (24) | 44 (22) | |

| Graduate school | 64 (10) | 30 (14) | 34 (17) | |

| No response | 124 (19) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous CPR training | ||||

| No | 113 (55) | 112 (56) | .95 | |

| Yes–within past 2 yrs | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes–2 to 5 yrs | 22 (11) | 18 (9) | ||

| Yes–5 to 10 yrs | 13 (6) | 11 (6) | ||

| Yes–more than 10 yrs | 59 (28) | 58 (29) | ||

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Subjects were excluded if they reported CPR training within the past 2 yrs (see Methods for full set of inclusion and exclusion criteria); prior CPR training was not assessed in our brief screening process but only collected after enrollment. p values represent statistical comparison between the standard and continuous chest compressions groups.

CPR Skill Assessment

After completing the training, subjects were asked to perform 2 mins of CPR on a standard skill-reporting manikin. A total of 396 subjects completed this assessment (Table 2); data from 13 subjects were excluded due to technical CPR-recording difficulties. CPR skills were comparable in both groups: the mean chest compression rate in the CC-CPR group was 87 ± 25 per min, and in the standard CPR group it was 93 ± 25 per min, while the mean chest compression depth was 34 ± 12 mm in the CC-CPR group and 35 ± 12 mm in the standard CPR group (p = .26). In the smaller cohort that was reassessed at 3 to 6 months, CPR skills were comparable, suggesting little skill degradation in either group within this timeframe. As expected in the two modes of CPR delivery, “hands-off” time (that is, time without chest compressions during CPR performance) was significantly smaller in the CC-CPR cohort than the standard CPR cohort.

Table 2.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills assessment after training

| CPR Characteristics | Initial Skills Testing

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Chest Compression CPR n = 204 | Standard CPR n = 192a | p | |

| Mean compression rate (n/min) | 87 ± 25 | 93 ± 25 | .02 |

| Mean compression depth (mm) | 34 ± 12 | 35 ± 12 | .26 |

| Total hands-off time (secs) | 16 ± 19 | 55 ± 16 | <.01 |

| Mean ventilations per minute | n/a | 5 ± 7 | n/a |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; n/a, not applicable. All values are shown ± SD. Some subject CPR data was excluded due to technical recording difficulties:

n = 10. p values represent a comparison between the continuous chest compression and standard CPR groups.

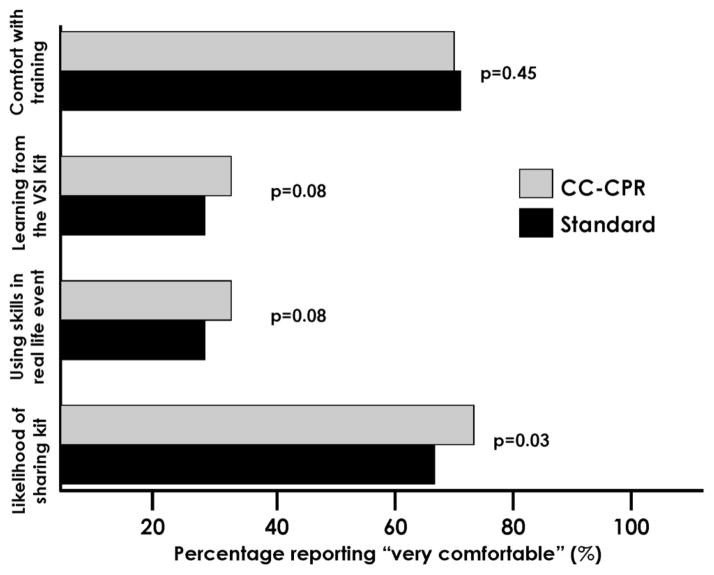

Comfort Level with Training

A Likert-scaled survey was administered after initial enrollment to assess subject comfort level with the respective modes of CPR training, as well as the likelihood of sharing the training kit with others for the purpose of secondary training (Fig. 2). Most subjects in both the CC-CPR and standard CPR cohort responded positively to the session, stating that the training was very easy (141 of 207 [68%] vs. 139 of 199 [70%], p = .45). There was a strong, although statistically nonsignificant, trend toward CC-CPR trainees feeling very comfortable with learning from the VSI kit compared to those learning standard CPR (71 of 207 [34%] vs. 57 of 199 [28%], p = .08). Similarly, CC-CPR trainees were more likely to rate themselves as very comfortable using their newly acquired skills in a future real-life event, than their standard CPR mode counterparts (71 of 207 [34%] vs. 57 of 199 [28%], p = .08). The CC-CPR trainees were significantly more likely to state that they were very likely to share the kit with their family and friends, as compared to their standard mode equivalent (152 of 207 [73%] vs. 133 of 199 [67%], p = .03).

Figure 2.

Trainee responses to post-training survey. Reponses in 5-point Likert scale were dichotomized into responses of 5 (“very comfortable”), vs. 1– 4, and those comparisons between the two cohorts of subjects are shown. CC-CPR, continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation; VSI, video self-instruction.

Qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses from the post-training survey yielded overall positive responses, such as “the training was very informative and engaging.” A coding of common subject response themes is shown in Table 3. Some of the subjects in both groups preferred the VSI CPR method of training to traditional CPR courses that they may have taken previously. A Likert-scaled survey was administered to those who refused training, in which the foremost self-perceived barrier was fear of performing CPR incorrectly (mean score 2.8 ± 1.4). Further discussion of these findings will be published elsewhere.

Table 3.

Categorization of open-ended survey responses after training

| Theme of Response | Number Responding

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Chest Compression CPR n = 207 | Standard CPR n = 199 | |

| CPR skills presented in a clear, concise manner | 21 | 23 |

| Training was very informative and engaging | 41 | 39 |

| Training was easy to understand | 57 | 50 |

| Preferred training method to older forms of CPR | 23 | 18 |

| Miscellaneous or no response | 65 | 69 |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Since the coding of responses into the above themes was subjective, no statistical comparisons were attempted.

Secondary CPR Training

To assess secondary training using the VSI kits, subjects were contacted by telephone at 1 month after enrollment. Of these, 21 had disconnected numbers, and 289 subjects were successfully contacted to complete this phase of follow-up, with 147 of 195 (75%) from the CC-CPR group and 142 of 190 (75%) from the standard CPR group (Table 4). Within the CC-CPR group, 147 subjects were contacted, 96 enrollees shared the kit with 291 additional individuals, conferring a mean of 2.0 ± 3.4 people trained per kit, and an actual range of 1–25 people trained per kit. Of the 142 subjects in the standard CPR group, 72 enrollees shared the kit with 174 additional individuals, resulting in a mean of 1.2 ± 2.2 people trained per kit. The difference in secondary training between recipients of CC-CPR training was significant compared to secondary training by recipients of standard CPR training (p = .03). Of the individuals who did not share the kit (n = 121), the majority of the individuals (n = 86) reported that they were “too busy” to share the kit with others. Of those that shared (n = 168), most of the individuals reported that they were comfortable or very comfortable sharing the kit with others (167 of 168, 99%).

Table 4.

Secondary training data from eligible subjects

| Training Data | Continuous Chest Compression Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation | Standard Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects who completed 1-month follow-up | 147 | 142 | |

| Subjects who shared video self-instruction kit with others | 96 | 72 | |

| Additional number of people trained by kit | 291 | 174 | |

| Mean number of people trained per kit | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 1.2 ± 2.2 | .03 |

| Range of people trained per kit | 1–25 | 1–15 |

Data represent self-reporting from subjects via telephone interview. p value represents a comparison between the continuous chest compression and standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation groups.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing two modes of CPR education, we have demonstrated that training laypersons in CC-CPR may yield several key benefits. Compared to training in standard CPR with ventilations, training in CC-CPR increased both trainee comfort with skills performance and motivation to share the CC-CPR training program, as well as generating significantly greater rates of secondary training of others in CPR techniques using the same self-instructional kits. Importantly, there was no clinically significant difference in objective metrics of chest compression quality comparing those who were trained in the two different modes.

To our knowledge, this work represents the first large-scale randomized trial involving “high-risk” laypersons, comparing educational outcomes from CC-CPR (also termed “Hands-only” CPR) and the “standard” form of CPR (30 compressions: two breaths in repeated cycles). The goal of our work was to assess the strengths of CC-CPR with respect to training strategy, not clinical outcome. A number of nonrandomized retrospective studies have suggested that CC-CPR may be the preferred clinical approach for lay-person CPR, especially when provided by dispatchers, since bystander delivery of CC-CPR has been associated with improved survival and neurologic outcome (11, 12, 24). This was more recently demonstrated by longitudinal work in Arizona, in which broad efforts to increase CC-CPR delivery were associated with a concomitant increase in sudden cardiac arrest survival (8). However, recent observational studies suggest decreased effectiveness of CC-CPR with delayed initiation of CPR and use of CC-CPR in cardiac arrest cases of “noncardiac” origin (e.g., respiratory arrest), although the same studies found similar rates of survival in both study populations when analyzing the populations as a whole (10, 25, 26). The American Heart Association has recently endorsed the performance of CC-CPR by laypersons “who are uncomfortable, unwilling, or untrained to perform standard CPR” (27, 28). It is important to note that resuscitation guidelines still recommend that educational efforts be focused on standard CPR, and very few investigations have addressed how layperson motivation and perspectives are affected by the mode of CPR training.

We have used a VSI CPR training approach in this investigation. Several studies have demonstrated that skill performance and retention from VSI CPR training is comparable to that of a traditional Basic Life Support class (29 –34). In addition, using VSI as an approach to layperson education affords a number of key advantages. VSI training can be conducted in a broad array of settings, including classrooms, large sports venues, or in hospital waiting areas, as described in our preliminary work. Training can be conducted in <30 mins without the need of a certified instructor. As such, the VSI kit provides a unique opportunity for secondary training, in that the VSI CPR kit can be shared with multiple individuals after initial training. A Danish study distributed 35,000 VSI kits to students (12 to 14 yrs old) and found that an additional 2.5 people were trained per pupil (23). In our current work, we found a lower magnitude of secondary training overall, possibly due to lesser motivation in the adult trainee population as compared to students. We also found that secondary training was significantly more widespread among trainees given CC-CPR instruction and kits compared to trainees given standard CPR instruction and kits, which suggests an increased interest among the CC-CPR cohort in sharing a new, simpler version of the lifesaving skill with their family members and friends that eschews mouth-to-mouth contact. Prior studies have suggested that mouth-to-mouth contact may serve as an important training and performance barrier to CPR (3–7).

More broadly, our work suggests the potential role of a healthcare-based model of VSI CPR training, in which family members of “higher risk” patients are offered CPR education before hospital discharge. Previous work from our group and others has explored this approach, which contrasts with the paradigm of CPR education in the school environment, in which trainees are much less likely to witness a cardiac arrest event over time following training (18, 35). Future education dissemination efforts should consider the hospital-based model and use of VSI CC-CPR training in parallel with other innovative approaches, such as the recent exploration of training using an abbreviated video strategy (so-called “ultrabrief” CPR training) (36) or a variation of the staged approach to resuscitation education (37, 38). While hospitals could implement such programs with little risk of harm, the optimal approach for broad dissemination remains to be fully elucidated. The appropriate combination and evolution of these strategies may hopefully serve to build a national model for widespread bystander CPR education.

Study Limitations

Several limitations of our work should be noted. First, secondary training was measured by participant self-reporting, which might be prone to recall bias and/or false reporting. Secondary training was assessed within a relatively short timeframe (1 month) to minimize recall bias, and the lack of financial remuneration and lack of in-person contact at this stage hopefully limited the tendency for false reporting. Second, we did not collect data on clinical outcomes, or whether CPR was actually performed by trainees. To collect these data would require a much larger cohort followed over a significantly longer time period, which we hope to accomplish in future work. Given the wealth of data supporting the benefit of promptly delivered CPR, it is reasonable to suggest that more widespread CPR training might lead to improved survival on a population basis.

CONCLUSIONS

In this randomized controlled trial of two modes of CPR training, we found that CC-CPR training using a VSI instructional strategy was associated with higher rates of secondary training. While this study supports the notion that the subjects felt comfortable with CC-CPR as a training approach, additional work is needed to look at retention and trainee confidence over a longer timeframe. This work provides additional support for the widespread use of CC-CPR training as a dissemination approach, and highlights an underutilized approach to CPR training of a “high-risk” segment of the population.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by a Clinical Research Program grant from the American Heart Association (0980018N).

Dr. Abella has received research funding and honoraria from Philips Healthcare and in-kind research support from Laerdal Medical Corporation. Drs. Abella and Bobrow have received research funding from the Medtronic Foundation, pertaining to improving statewide cardiac arrest monitoring and reporting. Dr. Bobrow has also received funding from the American Heart Association to study ultrabrief cardiopulmonary resuscitation video training.

We thank Lori Albright, James Andersen, Matthew Buchwald, Christopher Decker, Laura Ebbeling, Amanda Fredericks, Mariana Gonzalez, Lori Ingleton, Kristy Walsh, Benjamin Weisenthal, and Julie Xu for subject recruitment and assistance with data collection. We also thank the nurses and nurse managers at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, and Pennsylvania Hospital for all of their help and support.

Footnotes

The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, et al. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63– 81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–1431. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Eigel B, et al. Reducing barriers for implementation of bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association for healthcare providers, policymakers, and community leaders regarding the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2008;117:704–709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong YT, Anantharaman V, Lim SH, et al. Mass cardiopulmonary resuscitation 99 –survey results of a multi-organisational effort in public education in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2001;49:201–205. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaillancourt C, Stiell IG, Wells GA. Understanding and improving low bystander CPR rates: A systematic review of the literature. CJEM. 2008;10:51– 65. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500010010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locke CJ, Berg RA, Sanders AB, et al. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Concerns about mouth-to-mouth contact. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:938–943. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.9.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibata K, Taniguchi T, Yoshida M, et al. Obstacles to bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan. Resuscitation. 2000;44:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, et al. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010;304:1447–1454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong ME, Ng FS, Anushia P, et al. Comparison of chest compression only and standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Singapore. Resuscitation. 2008;78:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, et al. Conventional and chest-compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders for children who have out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: A prospective, nationwide, population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosier J, Itty A, Sanders A, et al. Cardiocerebral resuscitation is associated with improved survival and neurologic outcome from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in elders. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SOS-KANTO study group. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders with chest compression only (SOS-KANTO): An observational study. Lancet. 2007;369:920–926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewy GA, Zuercher M, Hilwig RW, et al. Improved neurological outcome with continuous chest compressions compared with 30:2 compressions-to-ventilations cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a realistic swine model of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007;116:2525–2530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohm K, Rosenqvist M, Herlitz J, et al. Survival is similar after standard treatment and chest compression only in out-of-hospital bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2007;116:2908–2912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg RA, Sanders AB, Kern KB, et al. Adverse hemodynamic effects of interrupting chest compressions for rescue breathing during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2001;104:2465–2470. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.098926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, et al. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiac-only resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007;116:2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallstrom A, Cobb L, Johnson E, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by chest compression alone or with mouth-to-mouth ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1546–1553. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blewer AL, Leary M, Decker CS, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training of family members before hospital discharge using video self-instruction: A feasibility trial. J Hosp Med. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jhm.847. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swor RA, Jackson RE, Compton S, et al. Cardiac arrest in private locations: Different strategies are needed to improve outcome. Resuscitation. 2003;58:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dracup K, Heaney DM, Taylor SE, et al. Can family members of high-risk cardiac patients learn cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:61– 64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dracup K, Moser DK, Doering LV, et al. A controlled trial of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for ethnically diverse parents of infants at high risk for cardiopulmonary arrest. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3289–3295. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson RE, Swor RA. Who gets bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a witnessed arrest? Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:540–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isbye DL, Rasmussen LS, Ringsted C, et al. Disseminating cardiopulmonary resuscitation training by distributing 35,000 personal manikins among school children. Circulation. 2007;116:1380–1385. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hüpfl M, Selig HF, Nagele P. Chest-compression-only versus standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1552–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, et al. Time-dependent effectiveness of chest compression-only and conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of cardiac origin. Resuscitation. 2011;82:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa T, Akahane M, Koike S, et al. Outcomes of chest compression only CPR versus conventional CPR conducted by lay people in patients with out of hospital cardiopulmonary arrest witnessed by bystanders: Nationwide population based observational study. BMJ. 2011;342:c7106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. Part 1: Executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S640–S656. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travers AH, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, et al. Part 4: CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S676–S684. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roppolo LP, Heymann R, Pepe P, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing traditional training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to self-directed CPR learning in first year medical students: The two-person CPR study. Resuscitation. 2011;82:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung CH, Siu AY, Po LL, et al. Comparing the effectiveness of video self-instruction versus traditional classroom instruction targeted at cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills for laypersons: A prospective randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Einspruch EL, Lynch B, Aufderheide TP, et al. Retention of CPR skills learned in a traditional AHA Heartsaver course versus 30-min video self-training: A controlled randomized study. Resuscitation. 2007;74:476– 486. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch B, Einspruch EL, Nichol G, et al. Effectiveness of a 30-min CPR self-instruction program for lay responders: A controlled randomized study. Resuscitation. 2005;67:31– 43. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batcheller AM, Brennan RT, Braslow A, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation performance of subjects over forty is better following half-hour video self-instruction compared to traditional four-hour classroom training. Resuscitation. 2000;43:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todd KH, Braslow A, Brennan RT, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of video self-instruction versus traditional CPR training. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson ME, Lie KG. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for family members of patients on cardiac rehabilitation programmes in Scotland. Resuscitation. 1999;40:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(98)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobrow BJ, Vadeboncoeur TF, Spaite DW, et al. The effectiveness of ultrabrief and brief educational videos for training lay responders in hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Implications for the future of citizen cardiopulmonary resuscitation training. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:220–226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith A, Colquhoun M, Woollard M, et al. Trials of teaching methods in basic life support (4): Comparison of simulated CPR performance at unannounced home testing after conventional or staged training. Resuscitation. 2004;61:41– 47. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chamberlain D, Smith A, Colquhoun M, et al. Randomised controlled trials of staged teaching for basic life support: 2. Comparison of CPR performance and skill retention using either staged instruction or conventional training. Resuscitation. 2001;50:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]