Abstract

Background:

Hair pigmentation is one of the most conspicuous phenotypes in humans ranging from black, brown, and blonde to red. Premature graying of hair occurs more commonly without any underlying pathology but is said to be inherited in autosomal dominant pattern. Premature graying has been shown to be associated with a few of the autoimmune disorders. A role for environmental factors and nutritional deficiencies has also been postulated. However, to date the exact etiology of premature graying has not been established.

Aim:

The objective of our study was to conduct an epidemiological and investigative study of premature graying of hair in higher secondary and pre-university school children of the semi-urban area.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 35 cases and controls were investigated for various parameter such as Hemoglobin, total iron binding capacity, serum ferritin (S. Ferritin), serum calcium (S. Ca), serum iron (S. Iron), vitamin B12, and vitamin D3 after taking informed consent. Epidemiological and investigations correlation was established using the Chi-square and Mann Whitney test and P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

Result:

Among the various laboratory parameters S. Ca, S. Ferritin and vitamin D3 were low in patients with premature graying of hair. There was significant high number of vitamin D3 deficient and insufficient among the cases compared to the controls.

Conclusion:

According to our study S. Ca, S. Ferritin, vitamin D3 may play a role in premature graying of hair in our society.

Keywords: Calcium, ferritin, premature graying of hair, vitamin D3

INTRODUCTION

Hair pigmentation is one of the most conspicuous phenotypes of humans.[1] The biological process of gray hair appears to be associated with the progressive loss of pigment producing cells.[2] Hair is said to gray prematurely when it occurs before the age of 20 in whites, 25 in Asians and 30 in Africans.[3] Although hair graying or canities is a common process occurring in people as they age, an unknown percentage of individuals experience premature graying from familial inheritance or pathologic conditions.[4]

Premature graying has been shown to be associated with various autoimmune (AI) disorders such as vitiligo, pernicious anemia, AI thyroid diseases, and premature aging syndromes like Werner's syndrome. Furthermore, studies have shown a role for environmental factors such as ultraviolet light, climate, smoking, drugs, trace elements, and nutritional deficiencies in the pathogenesis of premature graying.[5]

Trace element deficiencies lead to a spectrum of the clinical manifestations especially in skin and hair. Pigmentary changes and hair loss are important manifestations of deficiency states. Iron and vitamin B12 have been shown to affect hair growth and pigmentation. It has also been hypothesized that the premature graying is associated with osteopenia indicating a probable role for vitamin D3 and calcium.[6,7]

There are only a few epidemiological and investigative studies reported in the literature in relation to premature graying of the hair. In view of this, we conducted this epidemiological study in higher secondary and pre-university school children and also investigated for various laboratory parameters such as Hemoglobin (Hb), total iron binding capacity (TIBC), serum ferritin (S. Ferritin), serum calcium (S. Ca), serum iron (S. Iron), Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D3 in-patients and controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We obtained permission from the District Education Department and Health Department to conduct skin camps during antileprosy month (January 2011). All students of less than 20 years of age from 10 higher secondary and 7 pre-university schools of semiurban Ullal area of Mangalore taluk of coastal Karnataka were screened for various skin ailments including premature graying of hair. Free medicines were distributed for all the skin problems during this screening camp. Individual with premature graying of hair were instructed to visit the Dermatology department of Father Muller Medical College Hospital along with their parents/guardian for further investigations between January and December 2011. Similar age and sex matched controls from the same schools were also instructed to visit the department for investigations. Premature graying of hair was defined having a minimum of 5 gray hair fibers in a person less than 20 years of age. An exhaustive history, detailed examination and blood investigations were carried out in every patient enrolled after taking informed consent/assent from the patient and the parents. A scale format (mild (up to 50)/Moderate (50-100)/severe (more than 100)) was used to assess the severity. The data were analyzed by using the Chi-square and the Mann Whitney test. Patients who refused to give consent to undergo investigations were excluded from the study. Approval from the Institutional ethics committee was obtained prior to the study.

OBSERVATION AND RESULT

Epidemiological

A total of 4840 students of the age group 12-19 years were screened for various skin ailments with particular reference of premature graying of hair. Various skin problems were observed and treated in 1241 students. A total of 60 patients with premature graying of hair were found (prevelance –1.2%). Among these 35 patients gave consent to undergo further investigations who formed the study group and 35 age and sex matched controls were also investigated who formed the control group.

Among the 35 children 11.5% had mild, 65.7% had moderate and 23% had severe graying of hair. The mean age of studied cases was 16.8 years and mean age of onset of premature graying was 15 years. Male to female ratio was 1:1.1 indicating a no sex predilection. All the children had a moderate built and nourishment. Parental history of premature graying was present in 42.6% of patients and siblings were involved in 14.2% of patients. It is interesting to observe that 8 (22.85%) cases also had vitiligo lesions in other parts of the body.

Investigative

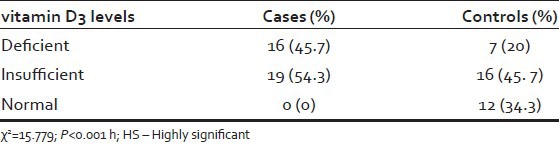

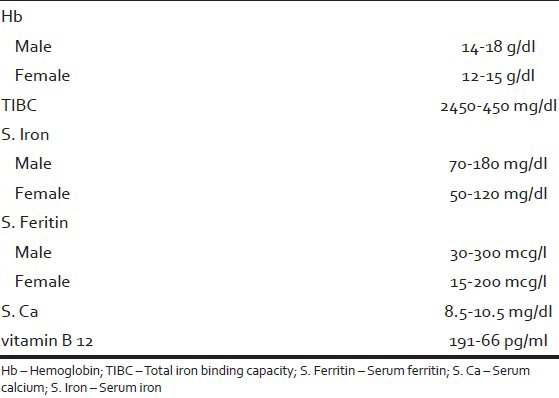

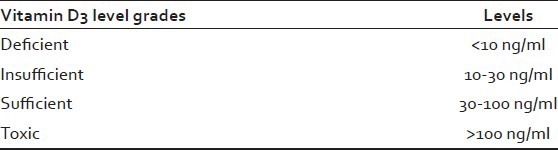

The investigative characteristics of 70 cases are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The normal values are mentioned in Tables 3 and 4. The mean S. ferritin and S. Calcium levels were significantly lower in the cases compared to control groups (S. Ferritin 36.88 + 35.11 vs. 60.93 + 53.08 mg/dl P = 0.03 and S. Calcium 9.47+.31 vs. 9.7/± 50 mg/dl, P = 0.018). There were significant high number of Vitamin D3 deficient (45.7% vs. 20%) and insufficient (54.3% vs. 45.7%) among the cases compared to the controls. However, no difference was found in between patients and controls in the mean Hb, TIBC, S. Iron and vitamin B12 levels.(Hb 12.93 + 1.74 vs. 13.43 + 1.42 g/dl, TIBC 363.60 + 50.18 vs. 356.31 + 341 mg/dl and Vitamin B12 479.70 + 214.82 vs. 458.37 + 265.19 pg/ml).

Table 1.

Comparision of Hb, TIBC, S. Iron, S. Ferritin, S. Ca and Vitamin B12 in cases and controls

Table 2.

Vitamin D3 levels in cases and controls

Table 3.

Normal values of Hb, TIBC, S. Iron, S. Ferritin, S. Calcium and vitamin B12 levels

Table 4.

Normal values of vitamin D3

DISCUSSION

The appearance of hair plays an important role in people overall physical appearance and self-perception. Premature graying of hair with unclear etiology is a common cause of referral to dermatologists. Premature graying occurs more commonly without any underlying pathology but is said to be inherited in autosomal dominant way. Hair pigmentation is one of the most conspicuous phenotype in humans ranging from black, brown, blonde to red.[1] This diversity of hair arises mostly from the quantity and ratio of black-brown melanin and reddish brown pheomelanin. It has been found to be associated with a wide range of syndrome like Werners syndrome and many AI disorders such as vitiligo, pernicious anemia, AI thyroiditis. The genetic basis for this diversity has recently attracted much attention among dermatologists, geneticists and pigment researchers, leading to the conclusion that interaction of several pigment genes play a major role in determining human hair color.[4,8,9,10,11,12] The diversity of hair pigmentation in humans lies mostly within physiological variations, differing among the three major ethnic population, African, Asian, and Caucasians.[1]

The biochemical aspect of human hair pigmentation was reviewed by Ortonne and Prota in 1993, but much progress has been made since then.[13] The role of pH in controlling mixed melanogonesis is now receiving much attention. Thus, it is known that tyrosinase activity are progressively suspended by lowering pH, with a shift to more pheomelanin phenotype.[14,15,16,17]

Another control point in mixed melonogenesis the concentration of cysteine in melanosomes.[18,19] The diversity of human hair pigmentation has proposed the hypothesis that pH and cysteine level of melanosomes play critical roles in determining the course of mixed melanosomes leading to dark, light or red hair phoneotype.[14] Deficiency in trace metal ions may also lead to hypopigmentation. Tyrosinase requires copper ion at its active center. It is thus likely that level of copper ion in melanocytes is necessary to maintain normal color. Menkes disease, caused by mutation in the Adenosine Triphosphate ATP 7A and ATP 7B genes has defect in copper transport, leading to usually the low level of copper in tissues.[20]

There has been analysis of hair from male Japanese patient with Menkes disease, containing melanin and pheomelanin level half of normal Japanese control, but his hair changed to dark brown after treatment with copper histidine.[21] In one of the studies, it was shows that there is a relationship between the mean serum copper concentration in the case group compared to the control group and it was lower in the case group.[5]

Iron deficiency may also result in pigmentation abnormality.[1] There has been a case report of 15-year-old Japanese girl who has segmented heterochromic hair in association with iron deficiency anemia.[22] Her melanin content recovered after iron supplementation. It has been shown that iron affects melanogenesis, for example, in the rearrangement of dopachrome to 5, 6 – dihydroxyindoles and the oxidative polymerization of the 5, 6 – dihydroxyindoles to melanin pigments. Moreover, studies provided evidence for the role of iron in the modulation of the activity of tyrosinase (new ref). It is reported that in a tautomerization reaction by dopachrome tautomerase, which is one of the later stages of melanin biosynthesis, the isomerization of dopachrome to dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid DHICA occurs. As informed by them, this enzyme is a metalloenzyme with ferrous in at its active site.[23] In our study, S. Ferritin levels were low although S. Iron, Hb and TIBC levels are normal indicating that iron supplements may help in the management of premature graying of hair. High dose oral zinc cation causes hair hypopigmentation without shifting pigment generation from eumelanogensis to pheomelanogenesis.[24]

Premature graying of hair is also associated to various disorder of the endocrine system.[25] Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that premature graying might be a marker for a variety of genetic and non-genetic conditions such as myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cancer, stroke, cirrhosis of liver and gastrointestinal problems.[26]

Cells of the hair follicle are rapidly dividing cell, and proliferation of the cells is dependent upon synthesis of DNA and therefore, on sufficient supply with vitamin B12 and Folic acid.[27] vitamin B12 stabilize the initial anagen phase of the hair follicle and might decrease post transplantational effluvium in hair restoration surgery.[28] Premature graying of hair may be a manifestation of pernicious anemia. However, our study didn’t reveal any significant difference in the serum vitamin B12 values of cases and controls. Premature hair graying has also been linked to decreased bone mineral density. Calcium has also been involved in some steps of melanogenesis.[29] This prompted us to investigate the levels of vitamin D3 and calcium in this study. To our surprise, we noted that s. ca and vitamin D3 levels were significantly lower in patients with premature graying of hair. Vitamin D3 levels were either deficient or insufficient in all the individuals of case group indicating probably an important role in pigmentation of the hair. We could not find any studies related to the role of vitamin D3 in premature graying of hair.

Many studies investigated the hair metal ions contents in different hair colors with controversial results. There are only a few studies assessing the level of trace elements in the body.[5,7] Naieni et al. in their study observed that low serum copper concentrations but not effect on S. Iron and zinc levels.[5] Our study showed the deficiency of S. Ferritin, although S. Iron and total iron biding capacity were normal. There was also a deficiency of S. Ca and vitamin D3 levels.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the present study shows a genetic predisposition in premature graying of hair and relation between low S. Ferritin, S. Ca and vitamin D3 levels. However, further studies may throw more light especially regarding the role of vitamin D3 in premature graying of hair.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was financially supported by IADVL Loreal pigmentation research grant 2011-12

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ito S, Wakamatsu K. Diversity of human hair pigmentation as studied by chemical analysis of eumelanin and pheomelanin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1369–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Commo S, Gaillard O, Bernard BA. Human hair greying is linked to a specific depletion of hair follicle melanocytes affecting both the bulb and the outer root sheath. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:435–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2004.05787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trüeb RM. Pharmacologic interventions in aging hair. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1:121–9. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEvoy B, Beleza S, Shriver MD. The genetic architecture of normal variation in human pigmentation: An evolutionary perspective and model. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R176–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fatemi Naieni F, Ebrahimi B, Vakilian HR, Shahmoradi Z. Serum iron, zinc, and copper concentration in premature graying of hair. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;146:30–4. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath ML, Sidbury R. Cutaneous manifestations of nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:417–22. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000236392.87203.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertazzo A, Costa C, Biasiolo M, Allegri G, Cirrincione G, Presti G. Determination of copper and zinc levels in human hair: Influence of sex, age, and hair pigmentation. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;52:37–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02784088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sturm RA. Molecular genetics of human pigmentation diversity. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R9–17. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook AL, Chen W, Thurber AE, Smit DJ, Smith AG, Bladen TG, et al. Analysis of cultured human melanocytes based on polymorphisms within the SLC45A2/MATP, SLC24A5/NCKX5, and OCA2/P loci. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:392–405. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerstenblith MR, Shi J, Landi MT. Genome-wide association studies of pigmentation and skin cancer: A review and meta-analysis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:587–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenzuela RK, Henderson MS, Walsh MH, Garrison NA, Kelch JT, Cohen-Barak O, et al. Predicting phenotype from genotype: Normal pigmentation. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55:315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branicki W, Liu F, van Duijn K, Draus-Barini J, Pośpiech E, Walsh S, et al. Model-based prediction of human hair color using DNA variants. Hum Genet. 2011;129:443–54. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0939-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortonne JP, Prota G. Hair melanins and hair color: Ultrastructural and biochemical aspects. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:82S–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12362884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ancans J, Tobin DJ, Hoogduijn MJ, Smit NP, Wakamatsu K, Thody AJ. Melanosomal pH controls rate of melanogenesis, eumelanin/phaeomelanin ratio and melanosome maturation in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268:26–35. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito S, Wakamatsu K. Human hair melanins: What we have learned and have not learned from mouse coat color pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:63–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DR, Spaulding DT, Glenn HM, Fuller BB. The relationship between Na(+)/H(+) exchanger expression and tyrosinase activity in human melanocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298:521–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheli Y, Luciani F, Khaled M, Beuret L, Bille K, Gounon P, et al. {alpha} MSH and Cyclic AMP elevating agents control melanosome pH through a protein kinase A-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18699–706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Marmol V, Ito S, Bouchard B, Libert A, Wakamatsu K, Ghanem G, et al. Cysteine deprivation promotes eumelanogenesis in human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:698–702. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chintala S, Li W, Lamoreux ML, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Sviderskaya EV, et al. Slc7a11 gene controls production of pheomelanin pigment and proliferation of cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10964–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502856102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bie P, Muller P, Wijmenga C, Klomp LW. Molecular pathogenesis of Wilson and Menkes disease: Correlation of mutations with molecular defects and disease phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2007;44:673–88. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomita Y, Kondo Y, Ito S, Hara M, Yoshimura T, Igarashi H, et al. Menkes’ disease: Report of a case and determination of eumelanin and pheomelanin in hypopigmented hair. Dermatology. 1992;185:66–8. doi: 10.1159/000247407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato S, Jitsukawa K, Sato H, Yoshino M, Seta S, Ito S, et al. Segmented heterochromia in black scalp hair associated with iron-deficiency anemia. Canities segmentata sideropaenica. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:531–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty AK, Orlow SJ, Pawelek JM. Evidence that dopachrome tautomerase is a ferrous iron-binding glycoprotein. FEBS Lett. 1992;302:126–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80421-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plonka PM, Handjiski B, Michalczyk D, Popik M, Paus R. Oral zinc sulphate causes murine hair hypopigmentation and is a potent inhibitor of eumelanogenesis in vivo. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:39–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen CJ, Holick MF, Millard PS. Premature graying of hair is a risk marker for osteopenia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:854–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.3.8077373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnohr P, Lange P, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Jensen G. Gray hair, baldness, and wrinkles in relation to myocardial infarction: The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Am Heart J. 1995;130:1003–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkov I, Press Y, Rudoy I. Vitamin B12 could be a “master key” in the regulation of multiple pathological processes. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:65–9. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krugluger W, Stiefsohn K, Laciak K. Vit B 12 activates wnt pathway in human hair follicle by induction of b catenin and inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 transcription. J Cosmet, Dermatol Sci Appl. 2011;1:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, Clearwater JM, Reid IR. Premature hair graying and bone mineral density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3580–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]