Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the accuracy and reliability of three continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems.

Research Design and Methods

We studied the Animas® (West Chester, PA) Vibe™ with Dexcom® (San Diego, CA) G4™ version A sensor (G4A), the Abbott Diabetes Care (Alameda, CA) Freestyle® Navigator I (NAV), and the Medtronic (Northridge, CA) Paradigm® with Enlite™ sensor (ENL) in 20 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. All systems were investigated both in a clinical research center (CRC) and at home. In the CRC, patients received a meal with a delayed and increased insulin dose to induce a postprandial glucose peak and nadir. Hereafter, randomization determined which two of the three systems would be worn at home until the end of functioning, attempting use beyond manufacturer-specified lifetime. Patients performed at least five reference finger sticks per day. An analysis of variance was performed on all data points ≥15 min apart.

Results

Overall average mean absolute relative difference (MARD) (SD) measured at the CRC was 16.5% (14.3%) for NAV and 16.4% (15.6%) for ENL, outperforming G4A at 20.5% (18.2%) (P<0.001). Overall MARD when assessed at home was 14.5% (16.7%) for NAV and 16.5 (18.8%) for G4A, outperforming ENL at 18.9% (23.6%) (P=0.006). Median time until end of functioning was similar: 10.0 (1.0) days for G4A, 8.0 (3.5) days for NAV, and 8.0 (1.5) days for ENL (P=0.119).

Conclusions

In the CRC, G4A was less accurate than NAV and ENL sensors, which seemed comparable. However, at home, ENL was less accurate than NAV and G4A. Moreover, CGM systems often show sufficient accuracy to be used beyond manufacturer-specified lifetime.

Introduction

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems are available for patients with diabetes for more than 10 years now. Most CGM systems assess glucose in the subcutaneous interstitial fluid, using the glucose oxidase approach. This provides minimal discomfort to patients and allows CGM usage at home.1 Although improvement in hemoglobin A1c with the use of CGM has been demonstrated,2 accuracy of glucose measurement is not yet good enough to allow patients to fully trust their CGM glucose readings, to such an extent that CGM manufacturers still recommend that patients use capillary blood glucose measurements before any treatment decisions are made (e.g., insulin dosing). The less than desirable accuracy of CGM systems also hampers endeavors to automate insulin administration by means of artificial pancreas systems, in which the CGM data are used by an algorithm to automatically determine and administer the appropriate amount of insulin needed to establish and maintain euglycemia. Obviously, artificial pancreas systems require highly accurate CGM data. The limited accuracy of CGM systems is, in part, caused by the compartment in which CGM systems measure glucose. Both a delay related to the measurement technique and the existence of a lag time between changes in blood glucose and interstitial fluid glucose are challenging CGM accuracy.3 Additionally, it has been shown that accuracy of needle-type CGM systems can be poor in the hypoglycemic range.4 Therefore, it is of utmost importance to assess the accuracy of CGM systems in a pertinent manner. Although efforts have been made, currently there is no reference procedure to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of CGM systems that are introduced into the market. Most premarket analyses of CGM systems have been done by means of Clarke error grid analysis (CEGA) and assessment of correlation between CGM glucose values and reference blood glucose values collected during nonstandardized and/or nonspecified conditions.5–7

The primary aim of this study was to assess the accuracy of the three widely used needle-type CGM systems in a way that includes both a highly standardized assessment within a clinical research center (CRC) as well as real-life usage at home. In addition, we assessed CGM accuracy within manufacturer-specified lifetime (MSL) and also beyond as it is possible to “reactivate” the CGM systems by tricking the CGM receiver into activating the old sensor as if a new sensor has been placed. It appears that patients do this routinely because of the poor reimbursement of CGM systems in many countries.8 In particular, patients who pay out of their own pocket for their CGM system try to use this expensive equipment as long as possible.

Materials and Methods

This was a multinational, randomized, open-label trial. Main inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes since at least 6 months, a body mass index of <35 kg/m2, and a hemoglobin A1c level of <10% (86 mmol/mol) at time of inclusion. Main exclusion criteria included pregnancy and use of medication that impacts glucose metabolism other than those used to treat their diabetes. Drugs that may impair enzymatic measurement of glucose by the sensors also had to be omitted during the investigation procedures (e.g., acetaminophen).

Twenty patients were included in this trial, four patients each in the five participating clinical centers of the AP@home consortium: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Graz, Austria; Montpellier, France; Neuss, Germany; and Padovua, Italy. All patients completed an inclusion visit during which informed consent was obtained and they received training in the use of the CGM systems. The CGM systems used in this trial included the Abbott Diabetes Care (Alameda, CA) Freestyle® Navigator I (NAV), the Medtronic (Northridge, CA) Paradigm® Veo™ system with Enlite™ (ENL) sensor, and the Animas® Vibe™ with Dexcom® G4 version A sensor (G4A) (a collaboration between Animas Corp. [West Chester, PA] and Dexcom Inc. [San Diego, CA]). All systems were calibrated according to manufacturer's specification with finger stick measurements using an Abbott Freestyle blood glucose meter. This meter was chosen as the calibration meter for all three systems because NAV can only be calibrated using its built-in blood glucose meter, which only accepts Freestyle strips. The other two CGM systems allow calibration against glucose values from any blood glucose meter. The Freestyle strips used for calibration of all devices by a given patient were from the same production lot. Patients were encouraged to avoid calibration directly after meals or strenuous activity and patients were also asked to perform self-measurement of blood glucose (SMBG) at least five times per day (pre-/postprandial and before the night), in addition to the SMBGs needed for (re)calibration, which were not included in the accuracy analysis. After placement of the sensors of all three CGM systems in the abdominal region, patients left the CRC and returned the following day (within 24 h after placement) to enter the CRC phase of the trial (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Study procedures during the clinical research center admission day (adapted from Wentholt et al.4).

Patients arrived at the CRC at 8:00 a.m., and sampling for reference blood glucose levels started immediately using the YSI 2300 STAT PLUS glucose and lactate analyzer (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH). Patients were then served a breakfast at 8:15 a.m., but their mealtime insulin dose was deliberately delayed until 8:45 a.m., at which time a prandial insulin dose was given accompanied by an additional 5 U of insulin. This procedure aimed to induce maximum excursions in postprandial glucose levels followed by a decline to low blood glucose levels. Blood was sampled every 15 min except between 8:00 and 8:15 a.m., 9:00 and 9:30 a.m., and 10:00 and 10:30 a.m., when blood was sampled every 5 min to capture baseline, peak glucose, and nadir glucose levels, respectively. The study day ended at noon, at which time one CGM system was randomly selected to be removed as continuing the home phase with all three systems was considered to be too cumbersome for patients. Thus, patients would return home with the two remaining CGM systems. Patients were instructed on how to reactivate the systems after MSL had ended in order to assess longevity and accuracy of the sensor readings beyond MSL. When both remaining CGM systems reached end of functioning, patients returned to the CRC, and CGM data were downloaded. “End of functioning” was defined as an average mean absolute relative difference (MARD) between CGM readings and SMBG results of >25% or >20 mg/dL in the hypoglycemic range (<70 mg/dL) on two consecutive days. Patients were provided with instructions on how to calculate the MARD, and these calculations were reviewed by study personnel. MARD calculations performed by patients were exclusively used to assess if CGM systems met the criteria that defined their end of functioning.

Upon completion of the trial, reference glucose meter measurements were matched with the corresponding CGM results, and MARD was calculated. Only CGM–reference pairs that were more than 15 min apart from each other were used for the analysis to prevent interdependency of data points.9 The maximum duration of CGM system use was recorded. Primary outcome measure was overall MARD assessed at the CRC and at home. Secondary outcome measures included MARD in the lower glycemic (<100 mg/dL), euglycemic (100–200 mg/dL), and hyperglycemic (>200 mg/dL) ranges (according to reference measurements). MARD per day of use and duration of CGM system usage were also assessed. An analysis of variance was performed to assess differences in accuracy between CGM systems. A Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to assess survival of CGM systems. Outcomes are given in mean (SD) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed in PASW Statistics version 18.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Technical data

CRC data from three patients using the NAV CGM device could not be uploaded and were excluded from the analysis.

CRC phase

Overall MARD (SD) at the CRC on Day 1 was 16.5% (14.3%) for NAV (number of data pairs=272), 20.5% (18.2%) for G4A (n=306), and 16.4% (15.6%) for ENL (n=306) (overall P<0.001), with both NAV and ENL performing better than G4A (P<0.001). There was no difference between NAV and ENL (P=0.791). When looking at CRC data pairs in the low glycemic range, NAV and ENL also showed lower MARD values than G4A: 17.4% (15.2%) (n=60) and 21.5% (24.0%) (n=64) versus 26.6% (25.7%) (n=64), respectively (overall P=0.005, with no significant difference between NAV and ENL [P=0.135]). In the euglycemic range, NAV and ENL also showed lower MARD values than G4A: 18.1% (17.5%) (n=115) and 16.4% (14.2%) (n=126) versus 21.0% (16.3%) (n=126) (overall P=0.006, with no significant difference between NAV and ENL [P=0.683]). MARD values in the hyperglycemic range were not significantly different between CGM systems: 14.0% (8.2%) (n=97) for NAV, 16.6% (13.8%) (n=116) for G4A, and 13.6% (9.4%) (n=116) for ENL (overall P=0.140).

Home phase

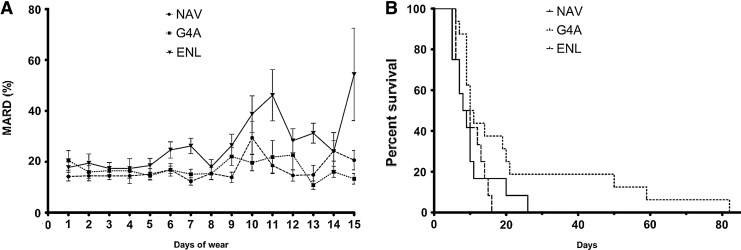

Overall MARD (SD) when assessed at home was 14.5% (16.7%) during the 5 days of MSL for NAV (n=329) and 16.5% (18.8%) during the 7 days of MSL for G4A (n=462) (Fig. 2). Both CGM systems performed better than ENL at 18.9% (23.6%) (n=312) during its 6 days of MSL (P=0.006). There was no difference between NAV and G4A during their respective MSL (P=0.534). Overall MARD (SD) after MSL was lower for G4A at 15.6% (17.7%) (n=1,162) versus NAV at 18.9% (17.0%) (n=337) (P=0.002) and ENL at 30.0% (26.0%) (n=174) (P<0.001).

FIG. 2.

(A) Mean absolute relative difference (MARD) per day per continuous glucose monitoring system: Medtronic Navigator (NAV), Dexcom G4 version A (G4A) sensor, and Abbott Enlite (ENL) sensor. Bars indicate SEM. (B) Survival curves of the three continuous glucose monitoring systems.

During MSL there is no effect of duration of use on the accuracy of the CGM systems, with MARD not being different between days of use for NAV (P=0.898), G4A (P=0.846), and ENL (P=0.153) (Fig. 2A).

G4A sensors displayed occasional extreme longevity with a maximum time until end of functioning of 82 days, versus 26 days for NAV and 16 days for ENL (Fig. 2B). However, median time until end of functioning was not different with 10.0 (1.0) days for G4A, 8.0 (3.5) days for NAV, and 8.0 (1.5) days for ENL (P=0.119).

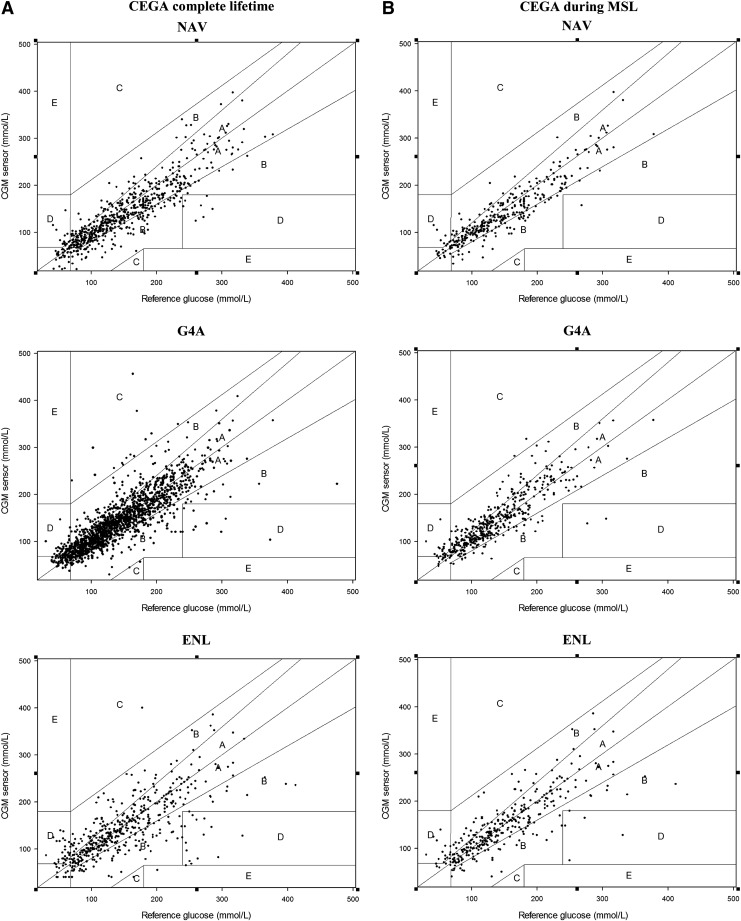

CEGA

The distribution of data pairs in CEGA zones per CGM system during MSL and during the entire CGM system lifetime is presented in Figure 3 and given in Table 1. During MSL there was no significant difference in distribution among the various CEGA zones (P=0.132).

FIG. 3.

Clarke error grid analysis (CEGA) per continuous glucose monitoring system during (A) complete lifetime and (B) manufacturer-specified lifetime (MSL): Medtronic Navigator (NAV), Dexcom G4 version A (G4A) sensor, and Abbott Enlite (ENL) sensor.

Table 1.

Distribution of Data Pairs in Clarke Error Grid Analysis Zones During the Entire Sensor Lifetime and During the Manufacturer-Specified Lifetime

| |

% of data pairs in Zone |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |

| During entire sensor lifetime | |||||

| NAV | 74.5 | 22.7 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 |

| G4A | 76.6 | 18.9 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 |

| ENL | 60.6 | 30.4 | 0.4 | 7.9 | 0.6 |

| During MSL | |||||

| NAV | 78.2 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| G4A | 75.3 | 20.1 | 0.4 | 4.1 | 0.0 |

| ENL | 68.8 | 25.6 | 0.0 | 5.7 | 0.0 |

MSL, manufacturer-specified lifetime.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this trial is the first head-to-head comparison of these three CGM systems. In a comprehensive assessment, we looked at accuracy, assessed both under CRC and home conditions, and longevity also beyond MSL. We showed earlier that accuracy of CGM systems assessed at the CRC differs from assessment at home.10 Indeed, a difference can be appreciated, with the NAV and ENL CGM systems outperforming the G4A system when assessed on Day 1 of use at the CRC, whereas analysis of the home phase shows superior accuracy for NAV and G4A with a relative underperformance of the ENL sensor. One part of the explanation of this difference is that CRC assessment of accuracy occurs during a relatively brief period of several hours with frequent sampling at predetermined times of reference values, encompassing the entire postprandial profile, whereas the home phase allows for accuracy assessment over several days but with reference values that are measured only a limited number of times per day and therefore cannot encompass the entire postprandial profile. Also, as can be seen in Figure 2, G4A has the largest MARD on Day 1 of use, but from Day 2 of use onward its MARD falls in between those of NAV and ENL until the end of MSL, although not statistically different from the NAV sensor. It appears as if the G4A system needs a longer warm-up period. This point may have been improved in the Dexcom G4 Platinum sensor (G4 version B), which recently acquired regulatory approval in both the United States and Europe.

A shortcoming of this study is the insufficient amount of data pairs in the hypoglycemic area. We used the method described by Wentholt et al.4 from which delaying and increasing the mealtime dose should have led to a period of minor hypoglycemia. However, we were less successful in achieving hypoglycemia in this trial. Future investigations following this procedure will need to use more aggressive insulin dosing in order to maximize the number of data pairs in the hypoglycemic range. In addition, we cannot rule out that the use of Freestyle strips favored NAV, but, unfortunately, because NAV can only be calibrated with these strips, their use was mandatory.

This study also shows that sensor life can be extended beyond MSL by reactivating the sensors when the sensor session has ended. It should be noted that all current CGM systems are unable to make the distinction between a reactivated sensor and a new sensor; therefore all information about past calibration points and performance of the sensor is likely lost. This, however, does not negate the fact that a large proportion of CGM systems can be used far beyond MSL, thus improving their cost-efficacy. Unfortunately, there is currently no way for the patient to predict which sensors can be used for longer periods of time, and patients need to actively make their own assessment about the accuracy of each individual sensor beyond MSL, using, for example, the criteria set out in this trial, rather than making a subjective assessment of sensor accuracy. In addition, although in this trial we did not observe problems with the sensor insertion site, even with prolonged use, we cannot recommend using a sensor beyond MSL without proper safety assessment. It is up to the manufacturers of CGM devices to carry out such investigations and consider prolonging the intended duration of use of their devices.

In conclusion, we showed that during CRC assessment the Dexcom CGM system was less accurate than the Abbott and Medtronic CGM systems, which seemed comparable. However, during assessment at home the Medtronic system was less accurate than the Abbott and Dexcom systems. In addition, our data showed that sensors can technically be used beyond MSL.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the European Community Framework Programme 7 (FP7-ICT-2009-4 grant number 247138).

Author Disclosure Statement

J.H.DeV. reports on having received grants and speaker fees from Medtronic. Y.M.L., J.K.M., W.D., T.P., A. Farret, J.P., E.R., D.B., A. Filippi, A.A., S.A., C.B., and L.H. have no competing interests. Y.M.L. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Y.M.L. wrote the manuscript and protocol, performed analysis, and gathered data. S.A., C.B., A. Farret, J.P., and A. Filippi gathered data. A.A., D.B., J.K.M., and W.D. gathered data and reviewed the manuscript. E.R., T.P., and L.H. reviewed the protocol and manuscript. J.H.DeV. reviewed the protocol and the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hermanides J. Devries JH. Sense and nonsense in sensors. Diabetologia. 2010;53:593–596. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1649-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langendam M. Luijf YM. Hooft L. Devries JH. Mudde AH. Scholten RJ. Continuous glucose monitoring systems for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1):CD008101. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008101.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wentholt IM. Hart AA. Hoekstra JB. Devries JH. Relationship between interstitial and blood glucose in type 1 diabetes patients: delay and the push-pull phenomenon revisited. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:169–175. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wentholt IM. Vollebregt MA. Hart AA. Hoekstra JB. Devries JH. Comparison of a needle-type and a microdialysis continuous glucose monitor in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2871–2876. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mastrototaro J. Shin J. Marcus A. Sulur G. The accuracy and efficacy of real-time continuous glucose monitoring sensor in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10:385–390. doi: 10.1089/dia.2007.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGarraugh GV. Clarke WL. Kovatchev BP. Comparison of the clinical information provided by the FreeStyle Navigator continuous interstitial glucose monitor versus traditional blood glucose readings. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:365–371. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zisser HC. Bailey TS. Schwartz S. Ratner RE. Wise J. Accuracy of the SEVEN continuous glucose monitoring system: comparison with frequently sampled venous glucose measurements. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1146–1154. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinemann L. Franc S. Phillip M. Battelino T. Ampudia-Blasco FJ. Bolinder J. Diem P. Pickup J. DeVries JH. Reimbursement for continuous glucose monitoring: a European view. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:1498–1502. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gough DA. Kreutz-Delgado K. Bremer TM. Frequency characterization of blood glucose dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:91–97. doi: 10.1114/1.1535411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luijf YM. Avogaro A. Benesch C. Bruttomesso D. Cobelli C. Ellmerer M. Heinemann L. Mader JK. DeVries JH. Continuous glucose monitoring accuracy results vary between assessment at home and assessment at the clinical research center. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:1103–1106. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]