Abstract

Background

Primary dysmenorrhea occurs 40%–50% in women of reproductive age. Acupuncture may assist treatment of menstrual pain.

Objective

This study compared the effects of the acupuncture program Chongmai, or Thoroughfare Vessel (TV), to sham acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

The current authors selected 3 groups of 10 patients each with primary dysmenorrhea for this comparative, prospective longitudinal study. The first group was treated at the TV points, the second group underwent sham acupuncture, and the third group (control) did not receive any kind of acupuncture. All groups were allowed to use steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Menstrual pain was measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS). The results were analyzed using a Student's-t test in GraphPad Prism 5.0. Acupuncture needles were applied at the following TV acupuncture points: (1) Gongsun (SP 4); (2) Qichong (ST30); (3) Neiguan (PC 6); and (4) Baihuanshu (BL 30), the metameric action point of the pelvic area. Electrical stimulation was applied through each needle at 120 Hz for 40 minutes.

Results

TV acupuncture, sham acupuncture, and/or NSAIDs substantially reduced pain in all 10 patients in each respective group (100%). TV acupuncture treatment reduced the symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea, and symptoms were reduced for at least 6 months. Application of needles at simulated points away from the TV acupuncture program did not reduce pain significantly.

Conclusions

TV acupuncture treatment can reduce the symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea, and the effect can last for 6 months.

Key Words: Primary Dysmenorrhea, Chongmai, Thoroughfare Vessel (TV), Sham Acupuncture, Pelvic Pain

Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is painful menstruation. It produces chronic pelvic pain of gynecological origin that occurs during menstruation and affects a large number of women during their reproductive years of life.1

Dysmenorrheic pain may affect daily activity adversely by limiting social, professional, and personal activity, and sexual activity is also affected frequently.2,3 Dysmenorrhea is classified as primary and secondary. “Box pelvic pain” occurs in primary dysmenorrhea during the menstrual phase in the absence of apparent organic pelvic pathology. Primary dysmenorrhea occurs in the first 6 months after menarche. Secondary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain that is associated with underlying disease and may occur during the menstrual period.4

Prostaglandin (Pg) synthesis produces uterine ischemia, which triggers the pain in primary dysmenorrhea. PgF2a increases during the menstrual cycle, and PG levels are correlated directly to pain intensity.5 Cyclo-oxygenases 1 and 2 mediate PG production. Overproduction of vasopressin hormone, which stimulates contraction of the myometrium, also contributes to dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea is a common complaint among young women, and it is widely prevalent (40%–50%). Work absence resulting from severity of symptoms occurs in <5% of women.6

Dysmenorrhea is commonly treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, NSAIDs do not control the dominant symptom, pain, in 20%–25% of cases. Acupuncture has been recommended as a nonpharmacological intervention. Acupuncture is a safe treatment that is free of major side-effects.7

Women are frequent users of complementary and alternative medicine in many countries. The U.S. National Institutes of Health has recently recommended acupuncture as an effective method for treating certain health problems, including menstrual-related pain.8 Numerous clinical reviews on dysmenorrhea management provide evidence of the efficacy of acupuncture treatment. However, diminution and duration of pain, and acupuncture points used are highly variable.9

This study compared the effects of acupuncture points in a Thoroughfare Vessel (TV) acupuncture program to sham acupuncture points, located outside of the zone of TV influence.

Methods

This work was performed in the acupuncture clinic at FES-Iztacala-UNAM (College of Professional Studies Iztacala, National Autonomous University of Mexico UNAM). Thirty women with primary dysmenorrhea participated in this controlled, prospective longitudinal study. All participants agreed to participate, having given prior written authorization and signed informed consent forms.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the FES-Iztacala-UNAM and adhered to ethical standards for research under the Rules of the General Law on Health Research, the ethical principles for medical research involving human beings emanating from the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association amended by the 52nd General Assembly, at Edinburgh, Scotland, in October 2000.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: healthy women ages 17– 24 and nulliparous without history or evidence of gynecological pathology; and no use of oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices. Patients who received anticoagulant therapy or who had pelvic pain with an associated pathology, such as endometriosis or uterine fibroid growths, were excluded. Participants in the study were introduced to the treatment at the beginning of menstrual pain.

Patient Groups

Ten patients were treated at TV acupuncture points, 10 patients underwent sham acupuncture outside of the zone of influence of TV, and 10 patients (controls) were not treated with any kind of acupuncture. All patients were allowed to use NSAIDs for pain control. All patients asked to record the amount and frequency of any analgesics (e.g., NSAIDs) used for pain. Follow-up examinations were performed during 6 menstrual cycles in the three groups of patients. All patients were interviewed once per month for 6 months after completion of treatment with acupuncture or NSAIDs.

Interventions

Sterilized, stainless-steel acupuncture needles (8 cm in length: 4 cm for the filament and 4 cm for the top body of the needle), which were double-wound with 28-gauge copper magnet wire10 (Material, Instruments and Accessories Reyes, Mexico City, Mexico) were used. These needles produced an electrical activity of 450 pico faradios (pF)11 at the points of the TV acupuncture program using the following TV points:12 (1) Gongsun (SP 4), (2) Qichong ST 30, (3) Neiguan (PC 6): and (4) Baihuanshu BL 30, which is the metameric action point of the pelvic area. All of the points were punctured at a depth of 4 cm. Acupuncture needles were applied to the skin surface after asepsis and antisepsis. The orientation of the needles was perpendicular at the SP 4 and BL 30 points, and was at a 45°-oblique angle at the PC 6 and ST 30 points. An electrostimulator (Material, Instruments and Accessories Reyes, Mexico City, Mexico) with a square-wave output pulse oscillation and a capability of 2 and 200 Hz was used. Electrical stimulation was applied through each needle at 120 Hz for 40 minutes. The first sessions of acupuncture were applied in the TV and sham acupuncture groups on day 1 of each subject's painful menstrual cycle. The second session of acupuncture was performed on day 14, during the second half of the menstrual cycle. Therefore, the patients were treated twice per cycle over 6 months.

Pain Measurement

A visual analogue scale (VAS) was selected for menstrual pain measurements because this scale is easy to use.13–15 The primary outcome measures included the Short-Form McGill Questionnaire and a numerical rating scale for pain intensity. The data were analyzed using a Student's t-test to compare the VAS values in GraphPad Prism 5.0 of the group receiving acupuncture.

Results

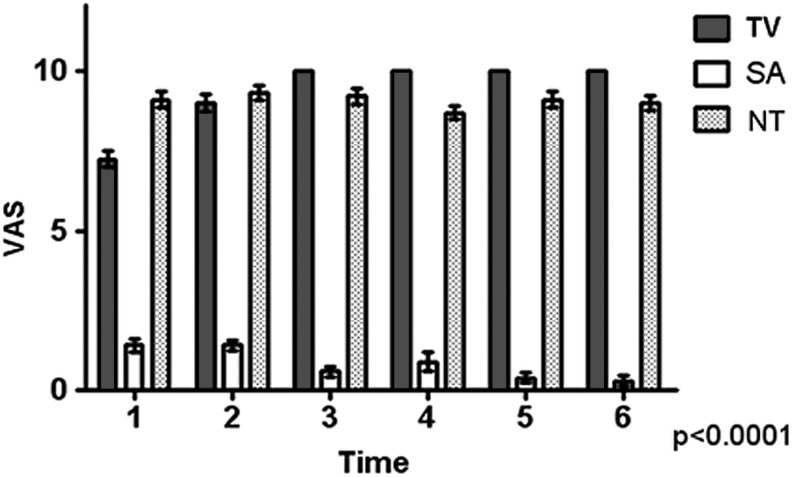

TV acupuncture, sham acpuncture, and/or NSAIDs substantially reduced pain in all 10 patients in each group (100%). TV significantly reduced pain intensity by 86% at time (T)1; 98.6% at T2; and 100% at T3, T4, T5, and T6. Each T was considered to be the average of the VAS first menstrual cycle; patients remained asymptomatic 6 months after treatment. The mean VAS score was similar in patients in the TV program group 10 minutes after treatment. Greater pain reduction occurred immediately after treatment, and a significant trend in pain reduction was observed over time (p<0.001). No patients in the TV acupuncture group reported NSAID use, and no pain occurred after the third treatment. As Figure 1 depicts, average NSAID use was significantly reduced at T1 (75%), T2 (75%), T3 (85%), T4 (90%), T5 (91%), and T6 (84%). In these patients pain reduction was only the effect of the NSAIDs, and common NSAIDs side-effects were reported.

FIG. 1.

Evaluation according to visual analogue scale (VAS) of treatment of primary dysmenorrhea comparing Thoroughfare Vessel program (TV), sham acupuncture (SA), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NT) for 6 cycles (N=10, p<0.0001). Patients who received treatment with TV after the third month had a complete disappearance of pain. Treatment with sham acupuncture did not produce improvement. The NSAID use produced pain reduction during the lifetime of the drug(s).

Average pain reductions were slight in the sham acupuncture group: 28% at T1; 10% at T2; 3% at T3; 9% at T4; and 7% at T5 and T6.

The side-effects of acupuncture treatment included immediate local sensitivity at some acupuncture points, but this sensitivity disappeared within minutes.

Discussion

Reductions in menstrual pain in patients with primary dysmenorrhea were observed after needle removal. Clear decreases in the VAS scores from baseline, compared to 30 minutes after treatment, were generally observed in TV group. These clinical observations suggested the efficacy of acupuncture at the TV acupuncture points in women with primary dysmenorrhea who did not want to take oral contraceptives or NSAIDs. Dysmenorrhea is caused by uterine ischemia, which is caused by myometrial contractions and increased secretion of Pgs.14 The acupuncture points of the TV acupuncture program affect the function of the pelvic plexus via stimulation of the T5–L1 sympathetic nerve fibers that modulate myometrial contractions. Acupuncture inhibits transmission of pain impulses. The pain relief noted in the TV acupuncture program group may have been the result of multiple mechanisms. Previous comparisons of unique acupuncture points, such as SP 6 and GB 39, and sham acupuncture points have shown a decrease in pain but no differences between true and sham acupuncture points. The analgesic duration is generally short-lived in these programs.14,15 No statistically significant differences in plasma PgE(2), PgF(2a), TXB(2), or 6-keto PgF(1a) levels or the ratios of PgF(2a)/PgE(2), and TXB(2)/6-keto PgF(1a) are observed after acupuncture at SP 6. The immediate analgesic effect of needling SP 6 may not be mediated by changes in Pg levels.14 In general, the SP 6, BL 32 and CV 2–4 points have been investigated, but variable results have been noted. The TV acupuncture program scheme in the current study matched 3 TV acupuncture points described previously by Helms.16 Helms used SP 4, ST 30, and PC 6 as did the current authors. Helms also used KI 3, ST 36, CV 2, and CV 4. BL 30—which is associated with the parasympathetic sacral plexus—was added, because this point influences vegetative neurological plexus hypogastric functions and exerts a specific action on the internal genitals.17

The TV acupuncture program uses specific acupuncture points that comprise a safe and effective alternative treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. This treatment is especially useful for women who experience adverse side-effects of oral contraceptive or NSAID treatment. The short- and long-term efficacy and safety of the TV treatment were compared to placebo at sham points. Other possible mechanisms and acupuncture points should be investigated, and qualitative studies of the treatment experience during primary dysmenorrhea should be performed. The current study results support the use of acupuncture in women with primary dysmenorrhea that is not relieved by conventional medical treatment.

Conclusions

The current authors conclude that treating the TV acupuncture points12 SP 4 ST 30, and PC 6, together with the BL 30 action point in the metameric pelvic area, produces significant reductions in acute menstrual pain in minutes in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. Application of needles at simulated points away from the TV acupuncture program did not reduce pain significantly. Use of the TV acupuncture program in patients with primary dysmenorrhea decreased pain for a prolonged time. Therefore, the results of the current support the design of controlled experimental trials in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adriana Arreola Jesús, CP, Department of University Extension of the FES Iztacala-UNAM, for the facilities that provided for the optimal performance of medical clinical acupuncture in this universitary educational institution. Thanks are also extended to José Federico Rivas Vilchis, PhD, academic secretary of the Graduate Division of Biological Sciences and Health of UAM-Iztapalapa, for the facilities provided for the development of this project.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Zondervan KT. Yudkin PL. Vessey MP. The prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women in the United Kingdom: A systematic review. BJOG. 1998;105(1):93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waller KG. Shaw RW. Endometriosis, pelvic pain, and psychological functioning. Fertil Steril. 1995;63(4):796–800. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson DJ. Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(1):55–58. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bettendorf B. Shay S. Tu F. Dysmenorrhea: Contemporary perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63(9):597–603. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31817f15ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: Advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):428–441. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison BW. Daniels SE. Kotey P. Cantu N. Seindenberg B. Rofecoxib, a specific cyclooxigenase-2 inhibitor, in primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(4):504–508. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu CZ. Xie JP. Wang LP, et al. Immediate analgesia effect of single point acupuncture in primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2011;12(2):300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceniceros S. Brown GR. Acupuncture: a review of its history, theories, and indications. South Med J. 1998;91(12):1121–1125. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SH. Hwang EW. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea: A systematic review. BJOG. 2010;117(5):509–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes-Campos MJ. Díaz-Toral LG. García-Miranda GA et al. Torus mandibular removed under acupuncture analgesia in patients with allergy to conventional anesthetics. Mexican J Anesthesiol. 2006;29(2):109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mussat M. [in French] Physiological Energetics of Acupuncture. 1st. Paris: Librairie le Francois;; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mussat M. [in French] Energetics of Living Systems Applied to Acupuncture. Paris: Medecine et Sciences Internationales; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong DL. Baker CM. Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14(1):9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi GX. Liu CZ. Zhu J. Guan LP. Wang DJ. Wu MM. Effects of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP 6) on prostaglandin levels in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(3):258–261. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181fb27ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirbagher-Ajorpaz N. Adib-Hajbaghery M. Mosaebi F. The effects of acupressure on primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(1):33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helms JM. Acupuncture for the management of primary dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(1):51–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore KL. Dalley AF. Anatomy, Clinical Orientation. 4th. Madrid: Panamericana; 2002. pp. 340–438. [Google Scholar]