Abstract

Bleeding from esophageal varices is a life threatening complication of portal hypertension. Primary prevention of bleeding in patients at risk for a first bleeding episode is therefore a major goal. Medical prophylaxis consists of non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol or carvedilol. Variceal endoscopic band ligation is equally effective but procedure related morbidity is a drawback of the method. Therapy of acute bleeding is based on three strategies: vasopressor drugs like terlipressin, antibiotics and endoscopic therapy. In refractory bleeding, self-expandable stents offer an option for bridging to definite treatments like transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Treatment of bleeding from gastric varices depends on vasopressor drugs and on injection of varices with cyanoacrylate. Strategies for primary or secondary prevention are based on non-selective beta-blockers but data from large clinical trials is lacking. Therapy of refractory bleeding relies on shunt-procedures like TIPS. Bleeding from ectopic varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia-syndrome is less common. Possible medical and endoscopic treatment options are discussed.

Keywords: Portal hypertension, Esophageal varices, Gastric varices, Portal hypertensive gastropathy, Gastric antral vascular ectasia-syndrome, Variceal bleeding, Endoscopy, Band ligation, Beta-blocker

Core tip: Gastrointestinal bleeding is a life threatening complication of portal hypertension. Primary prevention of bleeding in patients at risk for a first bleeding episode is therefore a major goal. The article gives a concise overview of possible bleeding sites in patients with portal hypertension. The diagnosis, prevention, therapy of acute bleeding and secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from esophageal and gastric varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy gastric antral vascular ectasia and ectopic varices are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

One of the major complications of portal hypertension is bleeding from esophageal varices. Bleeding from gastric or duodenal varices as well as bleeding from colonic varices or from portal hypertensive gastropathy is less common.

A lot of studies investigating prophylaxis and therapy of bleeding in portal hypertension have been published in the last years. This paper gives a concise overview of the current knowledge.

PRIMARY PROPHYLAXIS OF BLEEDING FROM ESOPHAGEAL VARICES

Definition

Primary prophylaxis of bleeding from esophageal varices is defined as a therapeutic intervention that aims at the prevention of the first variceal hemorrhage.

Diagnosis

At the time of the first diagnosis, about half of the patients with liver cirrhosis have esophageal varices (Figure 1)[1,2]. During the course of the disease about 90% of the patients develop esophageal varices. Variceal hemorrhage still carries a significant mortality of 7%-15%[3-5]. The identification and prophylactic treatment of patients at risk for esophageal bleeding is therefore mandatory[6].

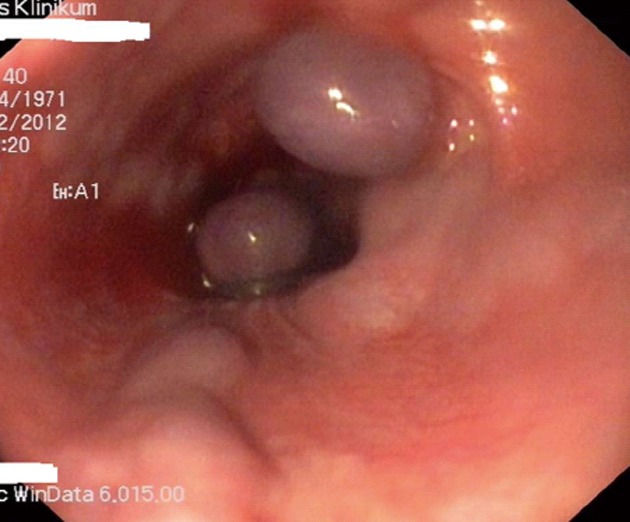

Figure 1.

Esophageal varices grade II in a patient with liver cirrhosis.

Risk factors for variceal bleeding are the diameter of the varix, presence of red wale signs and an impaired liver function[7-10]. Hemodynamic studies point at a close association of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) and the bleeding risk[9].

Every patient with newly diagnosed liver cirrhosis should underwent upper endoscopy for screening of esophageal and/or gastric varices[6]. In patients with esophageal varices with a diameter of more than 5 mm, prophylactic treatment should be initiated.

Prophylactic treatment is not necessary when only small varices (diameter below 5 mm) are present. Nevertheless, endoscopic follow-up is mandatory[6]. The overall incidence of esophageal varices is 5% per year[11,12]. Esophageal varices tend to increase in size in a linear fashion. One study including 258 patients with small varices and without a history of variceal bleeding found an increase in variceal size in 21%, 45% and 66% of the patients after 1.5, 3 and 4.5 years, respectively[13]. However, it has to be kept in mind that the course of the underlying liver disease is a major determinant of variceal progression[7,13]. The actual recommendation for surveillance in patients with compensated liver disease and small varices at the screening endoscopy is a follow-up examination after 1-2 years[6,14]. If the screening endoscopy showed no varices, a follow-up examination after 2-3 years is sufficient in patients with compensated liver disease[6,13,14].

Prophylaxis/therapy

Non-selective beta-blockers cause vasoconstriction of the splanchnic circulation by β2-receptor inhibition and decrease cardiac output by β1-receptor blockade. This leads to a decrease in portal venous inflow and thereby lowers portal pressure.

Beta-blocker therapy is not effective in preventing gastro-esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis[15]. There is only one study that showed that prophylaxis with a non-selective beta-blocker is effective in preventing the enlargement of small varices[16]. Patients with varices at risk of bleeding (diameter > 5 mm, presence of red-color-signs) should receive prophylactic treatment (see below), since the risk of bleeding is 30%-35% in two years. Effective prophylactic treatment reduces the risk of bleeding by about 50%[17].

A major drawback of beta-blocker therapy is that not all patients respond to beta-blockers with a reduction of the HVPG[18]. Clinical studies have shown that at most 50% of beta-blocker treated patients achieved a reduction of the HVPG below 12 mmHg or > 20% from baseline levels[18]. However, other effects of beta-blocker therapy besides the reduction of HVPG like a decrease in azygos blood flow or a decrease in bacterial translocation from the gut[19] may play a role in the prevention of variceal hemorrhage[20].

Endoscopic sclerotherapy and shunt procedures are obsolete in primary prophylaxis. Standard modalities are drug therapy with non-selective beta-blockers and endoscopic variceal band ligation (VBL) of varices.

Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol and nadolol were introduced for primary prophylaxis almost 30 years ago[17]. In recent years, the non-cardioselective vasodilating beta-blocker with mild intrinsic anti-α(1)-adrenergic activity carvedilol was shown to be at least as effective in lowering HVPG as propranolol[21] or nadolol plus nitrate[22] and to be as effective as VBL for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding[23]. A monotherapy with nitrates or a combination of beta-blockers and nitrates compared to beta-blockers alone has no benefit in primary prophylaxis[17,24]. Meta-analysis have shown a reduction of the bleeding risk by a non-selective beta-blocker of about 50%. Around 20% of patients suffer from intolerable side effects that require discontinuation of the drug. After discontinuation, the bleeding risk is not different from an untreated population. That makes an indefinite prophylactic therapy necessary[25]. The most important predictor for variceal bleeding in patients on a therapy with beta-blockers is the dose of the drug[26]. Patients should therefore receive the highest tolerated dose.

An effective alternative treatment for primary prophylaxis is endoscopic VBL[27-30]. One meta-analysis has shown, that compared with untreated controls, prophylactic VBL reduces the risks of variceal bleeding and mortality[31]. Several studies compared endoscopic VBL with propranolol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding[27-30]. Only one study that is controversially discussed because of some methodological flaws found a significant benefit for endoscopic VBL[29]. The other studies found no difference between beta-blockers and VBL concerning prophylaxis of bleeding[27,29,30]. A recently published Cochrane analysis that included 19 randomized trials found a slight beneficial effect for VBL, but that effect was not present when only full published paper articles were analyzed[32]. In terms of efficacy, VBL and non-selective beta-blocker therapy are considered to be equivalent.

Because of the low costs, ease of administration as well as the absence of procedure-related mortality, non-selective beta-blockers are recommended as first-line treatment for the primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding[17].

VBL is recommended in patients with serious side effects or intolerability of beta-blocker therapy as well as in patients with contraindications for drug therapy.

ACUTE BLEEDING FROM ESOPHAGEAL VARICES

Definition

Acute variceal bleeding is defined as: (1) active bleeding from esophageal varices at the moment of endoscopy; or (2) non-bleeding varices and blood in the esophagus/stomach are present and no other source of bleeding is found[33]. Recurrent bleeding is defined as rebleeding after 24-h of clinical absence of bleeding.

Therapy

Acute bleeding from esophageal varices is often a dramatic event. Most patients vomit blood but hematochezia and melena might be the only symptoms. Dependent on the amount of lost blood, patients might be hemodynamic instable and present in hemorrhagic shock. Today only 40% of patients die from exsanguinating bleeding. Most deaths are caused by complications of bleeding like liver failure, infections and hepatorenal syndrome[34,35]. Risk factors for an adverse course are the degree of liver dysfunction, creatinine, hypovolemic shock, active bleeding on endoscopy and presence of hepatocellular carcinoma[4,34-37]. Thus, the management of patients with acute variceal bleeding includes not only treatment and control of active bleeding but also the prevention of rebleeding, infections and renal failure[38].

If variceal bleeding is suspected, patients should be hemodynamically stabilized and receive medical treatment with vasopressors and antibiotic treatment[39-43]. In uncomplicated patients antibiotic therapy is done using quinolones[44]. High-risk patients with advanced liver disease (ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice, malnutrition) or previous therapy with quinolones should receive ceftriaxone[41]. Antibiotic treatment of patients with acute variceal bleeding does not only decreases mortality but also decreases the probability of rebleeding[42]. Transfusion of blood should be done with caution with a target hemoglobin level between 7 to 8 g/dL, since higher hemoglobin levels can increase portal pressure[45] and restrictive transfusion strategies are associated with better survival[46]. Patients with massive bleeding and/or patients who are somnolent should undergo endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation prior endoscopy to prevent aspiration pneumonia.

Available therapy options include medical and endoscopic treatment, balloon tamponade, placement of fully covered self-expandable metallic stents, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and surgical shunts. Nowadays, the initial approach is a combination of vasoactive drugs, antibiotics and endoscopic therapy[47].

Medical therapy

The aim of medical therapy is to reduce splanchnic blood flow and portal pressure. Drugs currently in use are vasopressin, somatostatin and, most important in Europe, terlipressin. Due to its short half-life, vasopressin has to be given as a continuous iv infusion. Relevant adverse effects include systemic vasoconstriction with serious implications like mesenteric or myocardial ischemia[48]. Application of vasopressin in combination with nitrates reduces the side effects associated with vasoconstriction[49,50]. Several studies have shown that the vasopressin treatment is effective in terms of bleeding control but does not affect mortality[48,51-53]. Terlipressin is a synthetic vasopressin analogue with a longer half-life and less adverse effects. Several studies have shown that terlipressin is effective in bleeding control and has a positive impact on survival[54-56]. Terlipressin achieves control of bleeding in 75%-80% and 67% of patients at 48 h and at 5 d, respectively[56,57]. It is given at a dose of 2 mg every 4 h for the first 48 h and could be continued for prevention of early rebleeding at a dose of 1 mg every 4 h for up to 5 d[57,58]. A recent study has shown a drop of serum sodium in the range of > 5 mEq/L in 67% of patients and of > 10 mEq/L in 36% of patients treated with terlipressin[59]. Therefore, serum sodium should be monitored in patients receiving terlipressin. Compared to vasopressin, terlipressin is more effective in control of esophageal bleeding[60,61] and compared to vasopressin plus nitrate[62] as well as compared to somatostatin it is comparable effective[63,64].

Somatostatin is given as an initial bolus of 250 μg followed by a 250 to 500 μg/h continuous infusion until a bleed-free period of 24 h is achieved[38]. Octreotide is a synthetic analogue of somatostatin with longer half-life. It is administered as an initial bolus of 25 μg, followed by an infusion of 25 to 50 μg/h[65]. Both, somatostatin and octreotide, have a good safety profile. Possible adverse effects include mild hyperglycemia and abdominal craps. Somatostatin is as effective as vasopressin in control of variceal bleeding; the safety profile is superior to vasopressin[66]. The combination of terlipressin and octreotide is not superior to a monotherapy with terlipressin[67].

In summary, the available data is most convincing for terlipressin, however, the direct comparison of terlipressin and octreotide revealed no superiority of terlipressin[68,69].

Endoscopic therapy

About 80%-90% of acute variceal bleeding episodes are successfully controlled by endoscopic therapy[70]. Nowadays, most important is endoscopic VBL, injection therapy using sclerosing agents like ethoxysklerol or cyanoacrylate is less commonly used. Ethoxysklerol is injected next to - not into - the varix. It causes local inflammation and scaring and thereby thrombosis and obliteration of the vessel. On the opposite, cyanoacrylate is injected directly into the varix, causing immediate obliteration of the vessel. Endoscopic band ligation is done using a transparent cap that is attached to the tip of the endoscope. By applying suction, the varix is then pulled into the cap and a rubber ring is thrown over the varix causing thrombosis and scaring of the vessel (Figure 2).

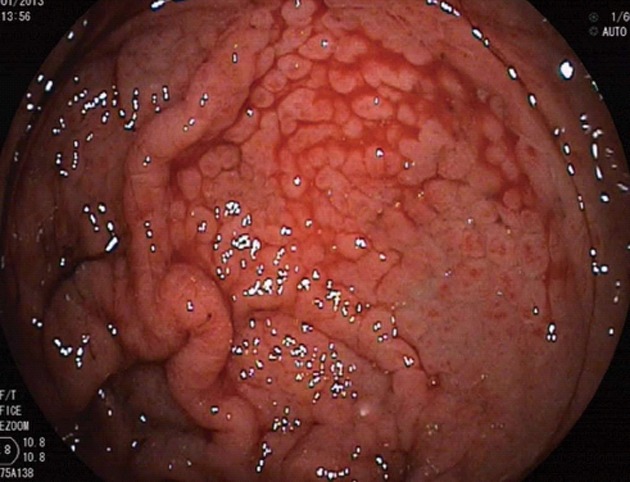

Figure 2.

Variceal band ligation of esophageal varices.

Before the introduction of VBL, ethoxysklerol injection was widely used in the treatment of acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Studies have shown that sclerotherapy was at least as effective as balloon tamponade[71,72]. The injection of cyanoacrylate is used as a second line therapy when VBL of variceal bleeding fails.

Endoscopic VBL was first carried out in 1988[73]. The method is now widely available and complications are - compared to sclerotherapy - less common[74]. The most frequent complications are superficial ulcerations and esophageal strictures. Bleeding after the rubber rings have been fallen off is less common. A disadvantage of the method is the impaired sight that is caused by the ligation system. Costs are - compared to sclerotherapy - higher. Mortality rates after VBL are lower as compared to sclerotherapy[75,76].

Balloon tamponade

The use of balloon tamponade for the treatment of acute esophageal variceal bleeding was introduced by Sengstaken et al[77] The Minnesota-tube is a modified version with an aspiration channel above the esophageal balloon. For uncontrolled bleeding from gastric varices, the Linton-Nachlas tube is preferred[78]. In the hand of the experienced user the method allows control of bleeding in most patients[79]. A major drawback of the method is the high amount of possible serious complications like necrosis and/or rupture of the esophagus as well as aspiration pneumonia[80]. Deflating of the balloon after six hours reduces the risk of complications. Due to the serious risks, balloon tamponade should only be applied by an experienced physician under fluoroscopic control. After all, balloon tamponade is only a bridging procedure until other, definite therapy options are available.

Self-expandable metal stents

The placement of fully covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) is an alternative to balloon tamponade. The SEMS is inserted over an endoscopic placed guidewire using a stent delivery device without the need of fluoroscopy[81]. SEMS controls bleeding by compression of the bleeding varices[81]. The stent can be left in place for up to two weeks and can be easily removed by endoscopy. The effectiveness in the control of refractory esophageal variceal bleeding has been shown in four case series[82-85]. The procedure is save with minor complications like esophageal ulcerations, compression of the bronchial system and stent migration into the stomach being described[82-85]. Like balloon tamponade, the procedure is reserved for patients with bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic treatment. It does not allow definite treatment of variceal bleeding due to the high percentage of patients with rebleeding after the SEMS has been removed, but has to be considered as an effective and safe bridging procedure that allows stabilization of the patient until definite treatment is possible.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

By TIPS placement a functional portacaval side-to-side shunt is established. TIPS is indicated in patients with refractory acute variceal bleeding that could not be sufficiently controlled by endoscopic and/or medical therapy and in patients with recurrent bleeding despite optimal endoscopic therapy. After TIPS insertion, bleeding is stopped in almost all of the affected patients[86-88]. The rate of recurrent bleeding after one year is 8%-18%[89-91]. However, TIPS insertion is a problem in patients with multi-organ failure and/or in patients with decompensated liver disease. In these patients, the 30-d-mortality rate is as high as 100%[86,88,92]. Disadvantages of the procedure are the risk of hepatic encephalopathy as well as TIPS dysfunction with the risk of recurrent bleeding[93,94]. A major improvement was the introduction of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) covered stents. These stents have higher rates of patency over time and mortality rates are lower[95]. A recently published trial has investigated the role of early TIPS in high-risk patients[96,97]. The multicenter study including 63 patients with esophageal hemorrhage and a high risk of treatment failure (Child B with active bleeding or Child C < 14 points) demonstrated that insertion of a PTFE covered TIPS within 72 h (preferable within 24 h) compared to combined endoscopic and vasoactive drug treatment decreased rebleeding (50% patients without rebleeding in the non-TIPS vs 97% in the TIPS group) and 1-year mortality (86% survival in the TIPS vs 61% in the non-TIPS group)[96].

Surgery

Surgical procedures in patients with acute or recurrent variceal bleeding are limited to a very small portion of patients in whom medical and/or endoscopic control of bleeding was not achievable and TIPS was no option because of technical or anatomical problems (e.g., complete thrombosis of the portal vein). Possible procedures are porto-systemic shunt operations[98] or staple transection of the esophagus[99]. Survival of patients who have undergone surgery is dependent on liver function but the mortality rate is as high as 80%.

SECONDARY PROPHYLAXIS OF ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BLEEDING

In patients who survive the first episode of esophageal hemorrhage, the risk of recurrent bleeding is as high as 60% with a mortality rate of up to 33%[100]. Prevention of rebleeding is therefore a major goal in patients in whom the initial bleeding episode has been successfully controlled.

Definition

Secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding is defined as the prevention of rebleeding from varices.

Medical therapy

Several studies are available that compared the non-selective beta-blockers propranolol or nadolol with no prophylaxis after initial bleeding[101-107]. Most of the studies found a reduction of the rebleeding risk as well as a reduction in mortality. Addition of nitrates further increased this positive effect[108]. Essential is a reduction of the HVPG of at least 20%, even if a reduction below 12 mmHg could not be achieved[26,109-111].

Endoscopic therapy

Several groups studied the effect of sclerotherapy for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding[105,112-114]. The comparison of sclerotherapy to medical therapy with a non-selective beta-blocker found a benefit for patients treated with sclerotherapy in two studies[115,116] and a slight but statistically not significant benefit for beta-blocker therapy[105,117,118]. Three more studies did not find a difference between the two treatment modalities[115,116,119].

For prophylaxis of recurrent bleeding, sclerotherapy is now replaced widely by VBL. Several studies have shown the superiority of VBL over sclerotherapy[74,76,120-124].

Comparing VBL to medical therapy with non-selective beta-blockers in combination with nitrates, two studies found medical therapy to be as effective[110] or more effective[125] than VBL. In contrast, one study found VBL to be advantageous over medical therapy[126]. From the pathophysiological point of view, the combination of VBL and medical therapy is an even more promising approach for secondary prophylaxis. This has been investigated in five studies[127-131]. Whereas two studies found combination therapy to be more effective than VBL alone[127,131] two more recent studies, that compared nadolol plus nitrates with combination treatment of drugs and VBL failed to demonstrate superiority of combination treatment[128,130]. Therefore, it seems that a clear recommendation for medial treatment alone, VBL alone or combination treatment of drugs and VBL cannot be made at the moment. A reasonable approach is to perform VBL alone in patients with contraindications for beta-blocker therapy or in patients who suffer from side effects of beta-blocker therapy. Patients who tolerate drug treatment well should be placed on a combination therapy.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

TIPS was compared to sclerotherapy[90,132-137] as well as to VBL[89]. In all but two studies[136,138] patients treated with TIPS had lower rates of recurrent bleeding. Three meta-analysis[139-141] summarized the available studies and found a significant lower probability of rebleeding in the TIPS treated patients. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was higher in the TIPS-group. A difference in mortality was not evident.

Surgery

Shunt surgery has been shown to be effective in the prophylaxis of rebleeding from esophageal varices. This has been shown for non-selective as well as for selective shunts (e.g., distal spleno-renal shunt) comparing operative shunts with no therapy or endoscopic sclerotherapy[99,142-147]. As in TIPS, the most important side effect was the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy.

One study[148] compared non-covered TIPS with a small diameter prosthetic porta-caval H-shunt. Both shunts led to an adequate reduction in portal pressure, but patency rates of the operative shunts were higher over time. This led to a lower rate of rebleeding as well as to a decrease in mortality in patients with the surgical shunt. A meta-analysis compared different porto-systemic shunts (TIPS, diverse surgical shunts) with endoscopic treatment[149]. All shunts were equally effective in reducing the risk of rebleeding. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was higher in patients who received a shunt procedure. TIPS was complicated by a high incidence of shunt dysfunction. Comparing the different shunt procedures, there was no difference in survival.

GASTRIC VARICES AND HYPERTENSIVE GASTROPATHY

In contrast to esophageal variceal bleeding, prevention and treatment of bleeding from gastric varices and from portal gastropathy is less well evaluated in clinical studies.

Definition

According to Sarin et al[150] gastric varices (Figure 3) are endoscopically classified as gastro-esophageal varices type I (lesser curvature), gastro-esophageal varices type II (greater curvature), isolated gastric varices type I (located in the gastric fundus) or isolated gastric varices type II (any location in the stomach except the gastric fundus).

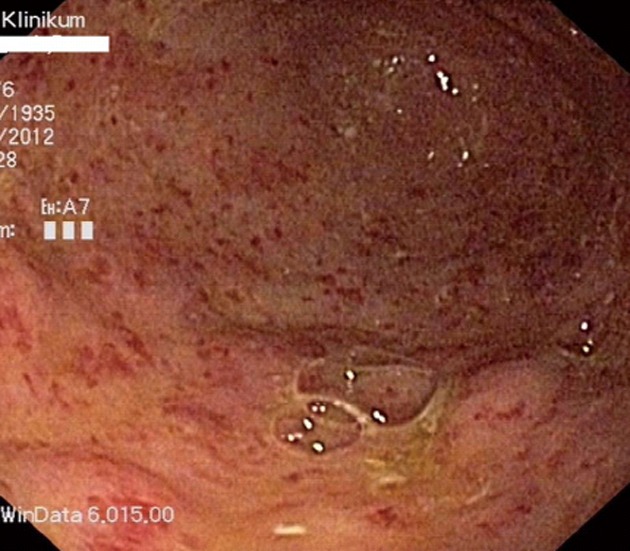

Figure 3.

Isolated gastric varices type I and portal hypertensive gastropathy in a patient with liver cirrhosis.

Gastric varices

The diagnosis of gastric varices is made by endoscopy. In case of doubt of the diagnosis, endosonography with Doppler sonography allows further differentiation. If only isolated gastric varices are present, the exclusion of portal or splenic vein thrombosis as the underlying cause is mandatory.

About on fifth of the patients with portal hypertension develop gastric varices[150]. In patients with gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension, bleeding from gastric varices is the cause in 5%-10% of patients[151]. The risk of the first bleeding from gastric varices is lower than the risk of first bleeding from esophageal varices (4% in one and 9% in three years)[152]. The risk of recurrent bleeding is dependent on the localization of the varix: isolated varices in the gastric fundus (53%) bear the highest risk of recurrent bleeding, followed by varices of the greater curvature (19%) and lesser curvature (6%)[150]. The prophylactic treatment of esophageal varices by VBL does not increase the risk of secondary gastric varices compared to propranolol[153].

Almost no data is available whether medical treatment for the primary prophylaxis of bleeding from gastric varices is effective. Pathophysiological considerations warrant the use of non-selective beta-blockers for this indication[151]. One trial including 27 patients with gastric varices studied the injection of cyanoacrylate for primary prophylaxis of bleeding from large gastric varices and found the injection of cyanoacrylate to be safe and effective in primary prophylaxis[154]. However, before recommending cyanoacrylate injection as prophylactic therapy, more studies are necessary.

Data for the treatment of acute bleeding from gastric varices is sparse. Therapy with terlipressin or somatostatin is recommend although controlled studies are lacking. The endoscopic treatment of choice is injection with cyanoacrylate[155-157]. Control of bleeding is as high as 90% and more effective than sclerotherapy or band ligation in one trial[158], whereas another study found VBL and cyanoacrylate injection equally effective in terms of control of acute bleeding but reported higher rebleeding rates in the VBL group[159]. Known complications of cyanoacrylate injection include mucosal ulcerations as well as thromboembolism. TIPS insertion is highly effective with control of bleeding in more than 90% of patients[160,161] and should be considered in patients in whom endoscopic therapy fails.

The use of non-selective beta-blockers and nitrates for prophylaxis of rebleeding was shown in one study to be not effective[162]. The comparison of cyanoacrylate with propranolol for secondary prophylaxis has shown no difference between the two treatment modalities in terms of rebleeding or mortality but found more complications in the cyanoacrylate group[163]. Another study compared TIPS with cyanoacrylate in patients with bleeding from gastric varices. TIPS was shown to be more effective for prevention of recurrent bleeding, with no difference in mortality[164]. These results are in contrast to a retrospective analysis that found TIPS and cyanoacrylate equally effective in controlling and preventing gastric variceal hemorrhage with no significant differences in survival[165]. Patients who received TIPS experienced significantly more long-term morbidity[165]. Nevertheless, the above mentioned studies have to be interpreted with caution, since they included patients with different types of gastric varices.

PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE GASTROPATHY

The diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy is made by endoscopy. Typical signs are mosaic, also called “snakeskin”, pattern of erythema. More severe forms present with red punctuate erythema, diffuse hemorrhagic lesions and/or brown spots that indicate submucosal hemorrhage[166]. Histopathologic features of portal hypertensive gastropathy are vascular ectasia of the mucosal and submucosal veins and capillaries[166]. The exact pathogenesis of portal hypertensive gastropathy is unknown. Important factors in the pathogenesis are the presence of portal hypertension as well as hyperemia of the gastric mucosa. Several authors assumed that the endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices aggravates portal hypertensive gastropathy[167]. The worsening is often transient and portal hypertensive gastropathy shows regression in more than 40% of patients after VBL[168]. The incidence of portal hypertensive gastropathy is around 80% in patients with liver cirrhosis[169]. Acute bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy (Figure 4) is a rare event, with an incidence of less than 3% in three years. One study that evaluated the cause of GI-bleeding in 1496 patients found bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy the cause in 0.8% of patients, accounting for 8% of non-variceal bleeding in patients with liver disease[170]. The probability of chronic bleeding is around 10%-15% in three years[6].

Figure 4.

Acute diffuse bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy in a patient with decompensated liver cirrhosis.

There is only one small trial that studied the effect of non-selective beta-blockers on portal hypertensive gastropathy[171]. Twenty-four patients with non-bleeding portal hypertensive gastropathy received 160 mg propranolol per day in a double-blind placebo controlled cross-over trial. Endoscopic grading of portal hypertensive gastropathy improved after propranolol in nine patients compared to three after placebo[171].

The therapy of acute bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy is mainly based on drugs that decrease portal pressure. In one study, 14 portal hypertensive patients with heavy diffuse bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy received propranolol in a dose of 24 to 480 mg per day. Within 3 d, bleeding ceased in 13 (93%) of patients[171]. Since the study did not have a control group of untreated patients, the results have to be interpreted with caution. A small study compared octreotide, vasopressin and omeprazole for therapy of acute bleeding. In this setting, octreotide was more effective than omeprazole or vasopressin[172]. Terlipressin was also shown to be effective in acute bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy[173].

No studies that investigated the role of endoscopic treatment using argon-plasma-coagulation in acute or recurrent bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy are available. If medical therapy fails, TIPS insertion or surgical shunt are an option[6,174,175].

In the secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy, one study including 54 patients showed that propranolol is effective in the prevention of rebleeding[176]. In the group of the propranolol treated patients 65% were free of rebleeding after one year compared to 38% in the control group. After 30 mo of follow-up, 52% of the patients in the propranolol group were free of rebleeding compared to 7% of the untreated patients[176].

In summary, the risk of bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy is low and primary prophylaxis is therefore not necessary. In patients with recurrent bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy, propranolol should be considered for secondary prophylaxis.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia-syndrome

Bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is an uncommon but sometimes severe cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. It accounts for 4% of non-variceal upper GI-bleeding[177].

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE-syndrome, also known as “watermelon stomach” or “honeycomb stomach”) is endoscopically as well as histologically distinguished form portal hypertensive gastropathy. In most patients, the diagnosis of GAVE is easily made on endoscopy. In case of diagnostic uncertainty, the so called GAVE-score that defines histological changes helps to distinguish the both entities[177]. GAVE-syndrome is most often found in older women and is associated with autoimmune disorders in about 60% of patients[178]. Liver disease is a risk factor for the development of GAVE-syndrome, but only 30% of affected patients suffer from liver cirrhosis[179]. On endoscopy (Figure 5), linear red streaks running longitudinally in the gastric antrum are apparent (“watermelon stomach”). In patients with liver cirrhosis the mucosal pattern is often more diffuse (“honeycomb stomach”)[180]. The lesion consists of ectatic vessels of the mucosa with focal thrombosis surrounded by fibromuscular hyperplasia[181]. The pathogenesis of GAVE is not well known. Hypothesis for the pathogenesis include mechanical stress[182], humoural[183] and autoimmune factors[184]. Portal hypertension per se does not seem to be a risk factor for GAVE[185,186].

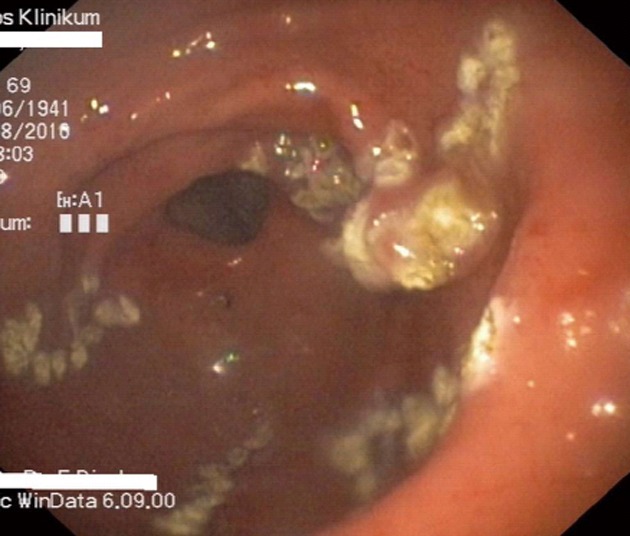

Figure 5.

Typical appearance of a watermelon stomach in a patient with gastric antral vascular ectasia-syndrome and compensated liver cirrhosis.

Different drugs have been used in the treatment of bleeding from GAVE. A small controlled cross-over trial has shown estrogen-progesterone to be highly effective in GAVE related bleeding[187]. Another study confirmed these findings[188]. However, the therapy has to be maintained on a long-term basis since a dose reduction results in recurrent bleeding[189]. Moreover, long-term hormonal treatment is associated with an increased risk for breast and endometrial cancer[190]. One small trial showed octreotide to be effective in bleeding from GAVE[191], but another study failed to confirm the efficacy of octreotide[192].

Treatment consists mainly of endoscopic measures like argon plasma coagulation (APC) (Figure 6), or laser photoablation of the lesions[193,194]. Endoscopic treatment using (Nd: YAG) laser has been shown to be effective in bleeding from GAVE in several studies[195-198]. The treatment is relatively safe, complications like perforation or pyloric stenosis are infrequent[199]. Disadvantages of the method are the high costs and the need for a long training period. Argon plasma coagulation has therefore widely replaced laser therapy in the treatment of GAVE related bleeding. The procedure is easy to use, relatively cheap and widely available as well as safe. The efficacy of APC in the treatment of bleeding from GAVE is very high (90%-100% in two studies[194,200]). On average, 2.5 sessions are necessary for successful eradication of the lesions[193,194,201]. Three studies using endoscopic band ligation for the treatment of GAVE related bleeding are available[202-204]. Band ligation was shown to be effective in all trials but a study with sufficient patient numbers comparing band ligation to APC treatment is missing. Lowering portal pressure by TIPS-insertion is not effective in chronic bleeding from GAVE[179,205]. Surgery (antrectomy) is efficient in bleeding from GAVE[206] but bears a significant morbidity and mortality and is therefore reserved for patients with recurrent bleeding despite therapy with argon plasma coagulation.

Figure 6.

Endoscopic treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia with argon plasma coagulation therapy.

ECTOPIC VARICES

Definition

Ectopic varices are dilated porto-venous vessels of the gastrointestinal mucosa that are located outside of the esophagus or the stomach.

Ectopic varices have their origin from preexisting small veins of the gastrointestinal mucosa that are porto-systemic collaterals between the portal vein and the inferior vena cava. In the majority of cases, portal hypertension or an extrahepatic obliteration of the portal vein are the cause for the development of ectopic varices.

Diagnosis

Bleeding from ectopic varices is a rare event. It accounts for 1%-5% of all gastrointestinal bleeding episodes in patients with portal hypertension[207,208]. Endoscopy is the most important diagnostic tool. In patients with portal hypertension, acute bleeding and negative findings on upper endoscopy, bleeding from ectopic varices has to be considered. In these patients, accurate examination of the duodenum is mandatory. Examination of the jejunum makes double-balloon enteroscopy necessary.

Colonoscopy is the principal method for the diagnosis of colonic varices. One study found rectal varices via endoscopy in 43% and via EUS in 75% of patients with portal hypertension, pointing out that rectal varices might be overlooked by conventional endoscopy[209].

In patients in whom bleeding from ectopic varices is assumed but endoscopy was negative, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) with NMR-angiography is the diagnostic tool of choice and allows the identification of ectopic varices in most patients.

Therapy

Sclerotherapy/injection therapy: Therapy of ectopic varices is mainly based on sclerotherapy or injection therapy. Controlled studies which method is best are not available but case reports showed that both sclerotherapy with ethoxysklerol as well as injection of the varix with cyanoacrylate are feasible[210-213].

Band ligation may be useful for temporary hemostasis[209,214] in duodenal varices but rebleeding of duodenal varices is a problem with ligation therapy. Additional treatment following band ligation for duodenal varices is therefore mandatory.

Surgery and TIPS: Porta-caval shunts are effective therapy measures in recurrent bleeding from ectopic varices[147,215,216]. Another option in patients without portal vein thrombosis is TIPS-insertion. Several case reports that show that TIPS is an effective option in the treatment of ectopic varices have been published[217-220].

Interventional radiology: Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (B-RTO) was successfully performed for patients with duodenal varices[221,222]. B-RTO can obliterate not only varices but also the afferent and efferent veins and should be considered for treating duodenal varices.

Medical therapy: From a pathophysiological point of view the application of beta-blockers does makes sense in patients with ectopic varices, but no data from controlled trials that investigate the role of non-selective beta-blockers and/or nitrates are available.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Fausto C, Issa IA, Karaman A S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

References

- 1.Calès P, Pascal JP. Natural history of esophageal varices in cirrhosis (from origin to rupture) Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1988;12:245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–354. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, Aracil C, Catalina MV, Garci A-Pagán JC, Bosch J. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augustin S, Altamirano J, González A, Dot J, Abu-Suboh M, Armengol JR, Azpiroz F, Esteban R, Guardia J, Genescà J. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1787–1795. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, Gómez C, López-Balaguer JM, Gonzalez B, Gallego A, Torras X, Soriano G, Sáinz S, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Franchis R. Updating consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno III Consensus Workshop on definitions, methodology and therapeutic strategies in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2000;33:846–852. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleber G, Sauerbruch T, Ansari H, Paumgartner G. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis: a prospective follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1332–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkel C, Bolognesi M, Bellon S, Zuin R, Noventa F, Finucci G, Sacerdoti D, Angeli P, Gatta A. Prognostic usefulness of hepatic vein catheterization in patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:973–979. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauerbruch T, Wotzka R, Köpcke W, Härlin M, Heldwein W, Bayerdörffer E, Sander R, Ansari H, Starz I, Paumgartner G. Prophylactic sclerotherapy before the first episode of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:8–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807073190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen E, Fauerholdt L, Schlichting P, Juhl E, Poulsen H, Tygstrup N. Aspects of the natural history of gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis and the effect of prednisone. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:944–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Amico G, Luca A. Natural history. Clinical-haemodynamic correlations. Prediction of the risk of bleeding. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;11:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3528(97)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoli M, Merkel C, Magalotti D, Gueli C, Grimaldi M, Gatta A, Bernardi M. Natural history of cirrhotic patients with small esophageal varices: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:503–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biecker E, Classen L, Sauerbruch T, Schepke M. Does therapy of oesophageal varices influences the progression of varices? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:751–755. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32830fe491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Grace ND, Burroughs AK, Planas R, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Patch D, Matloff DS, et al. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2254–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merkel C, Marin R, Angeli P, Zanella P, Felder M, Bernardinello E, Cavallarin G, Bolognesi M, Donada C, Bellini B, et al. A placebo-controlled clinical trial of nadolol in the prophylaxis of growth of small esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:476–484. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Tsao G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:726–748. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG, Hernandez-Guerra M, Dell’Era A, Bosch J. Pharmacological reduction of portal pressure and long-term risk of first variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:506–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thalheimer U, Triantos CK, Samonakis DN, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Infection, coagulation, and variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Gut. 2005;54:556–563. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feu F, Bordas JM, Luca A, García-Pagán JC, Escorsell A, Bosch J, Rodés J. Reduction of variceal pressure by propranolol: comparison of the effects on portal pressure and azygos blood flow in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1993;18:1082–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobolth L, Møller S, Grønbæk H, Roelsgaard K, Bendtsen F, Feldager Hansen E. Carvedilol or propranolol in portal hypertension? A randomized comparison. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:467–474. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.666673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM, Yu HC. Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1681–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripathi D, Ferguson JW, Kochar N, Leithead JA, Therapondos G, McAvoy NC, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Hislop WS, Mills PR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology. 2009;50:825–833. doi: 10.1002/hep.23045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.García-Pagán JC, Morillas R, Bañares R, Albillos A, Villanueva C, Vila C, Genescà J, Jimenez M, Rodriguez M, Calleja JL, et al. Propranolol plus placebo versus propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the prevention of a first variceal bleed: a double-blind RCT. Hepatology. 2003;37:1260–1266. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraczinskas DR, Ookubo R, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, Richardson CR, Matloff DS, Rodés J, Conn HO. Propranolol for the prevention of first esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a lifetime commitment? Hepatology. 2001;34:1096–1102. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abraldes JG, Tarantino I, Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Rodés J, Bosch J. Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long-term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:902–908. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo GH, Chen WC, Chen MH, Lin CP, Lo CC, Hsu PI, Cheng JS, Lai KH. Endoscopic ligation vs. nadolol in the prevention of first variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lui HF, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Jalan R, Hislop WS, Mills PR, Finlayson ND, Macgilchrist AJ, Hayes PC. Primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial comparing band ligation, propranolol, and isosorbide mononitrate. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:735–744. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarin SK, Lamba GS, Kumar M, Misra A, Murthy NS. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:988–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schepke M, Kleber G, Nürnberg D, Willert J, Koch L, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Hellerbrand C, Kuth J, Schanz S, Kahl S, et al. Ligation versus propranolol for the primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;40:65–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imperiale TF, Chalasani N. A meta-analysis of endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2001;33:802–807. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gluud LL, Krag A. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD004544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004544.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jalan R, Hayes PC. UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2000;46 Suppl 3-4:III1–III15. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.suppl_3.iii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Augustin S, Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, González A, Saperas E, Dot J, Abu-Suboh M, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR, Esteban R, et al. Predicting early mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage based on classification and regression tree analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Amico G, De Franchis R. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003;38:599–612. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard B, Cadranel JF, Valla D, Escolano S, Jarlier V, Opolon P. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1828–1834. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cárdenas A, Ginès P, Uriz J, Bessa X, Salmerón JM, Mas A, Ortega R, Calahorra B, De Las Heras D, Bosch J, et al. Renal failure after upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis: incidence, clinical course, predictive factors, and short-term prognosis. Hepatology. 2001;34:671–676. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García-Pagán JC, Reverter E, Abraldes JG, Bosch J. Acute variceal bleeding. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:46–54. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655–1661. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaise M, Pateron D, Trinchet JC, Levacher S, Beaugrand M, Pourriat JL. Systemic antibiotic therapy prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1994;20:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gómez C, Durandez R, Serradilla R, Guarner C, Planas R, Arroyo V, Navasa M. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1049–1056; quiz 1285. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Kuo BI, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:746–753. doi: 10.1002/hep.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Tur-Kaspa R, Paul M, Yahav J, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic inpatients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:193–200. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rimola A, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142–153. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castañeda B, Morales J, Lionetti R, Moitinho E, Andreu V, Pérez-Del-Pulgar S, Pizcueta P, Rodés J, Bosch J. Effects of blood volume restitution following a portal hypertensive-related bleeding in anesthetized cirrhotic rats. Hepatology. 2001;33:821–825. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepción M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, Graupera I, Poca M, Alvarez-Urturi C, Gordillo J, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bañares R, Albillos A, Rincón D, Alonso S, González M, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Salcedo M, Molinero LM. Endoscopic treatment versus endoscopic plus pharmacologic treatment for acute variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:609–615. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conn HO, Ramsby GR, Storer EH, Mutchnick MG, Joshi PH, Phillips MM, Cohen GA, Fields GN, Petroski D. Intraarterial vasopressin in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a prospective, controlled clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosch J, Groszmann RJ, García-Pagán JC, Terés J, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Mas A, Rodés J. Association of transdermal nitroglycerin to vasopressin infusion in the treatment of variceal hemorrhage: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hepatology. 1989;10:962–968. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gimson AE, Westaby D, Hegarty J, Watson A, Williams R. A randomized trial of vasopressin and vasopressin plus nitroglycerin in the control of acute variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1986;6:410–413. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fogel MR, Knauer CM, Andres LL, Mahal AS, Stein DE, Kemeny MJ, Rinki MM, Walker JE, Siegmund D, Gregory PB. Continuous intravenous vasopressin in active upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:565–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mallory A, Schaefer JW, Cohen JR, Holt SA, Norton LW. Selective intra-arterial vasopression in fusion for upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage: a controlled trial. Arch Surg. 1980;115:30–32. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1980.01380010022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merigan TC, Plotkin GR, Davidson CS. Effect of intravenously administered posterior pituitary extract on hemorrhage from bleeding esophageal varices. A controlled evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1962;266:134–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196201182660307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levacher S, Letoumelin P, Pateron D, Blaise M, Lapandry C, Pourriat JL. Early administration of terlipressin plus glyceryl trinitrate to control active upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Lancet. 1995;346:865–868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Söderlund C, Magnusson I, Törngren S, Lundell L. Terlipressin (triglycyl-lysine vasopressin) controls acute bleeding oesophageal varices. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:622–630. doi: 10.3109/00365529009095539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ioannou GN, Doust J, Rockey DC. Systematic review: terlipressin in acute oesophageal variceal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:53–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Escorsell A, Ruiz del Arbol L, Planas R, Albillos A, Bañares R, Calès P, Pateron D, Bernard B, Vinel JP, Bosch J. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of terlipressin versus sclerotherapy in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding: the TEST study. Hepatology. 2000;32:471–476. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Escorsell A, Bandi JC, Moitinho E, Feu F, García-Pagan JC, Bosch J, Rodés J. Time profile of the haemodynamic effects of terlipressin in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 1997;26:621–627. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solà E, Lens S, Guevara M, Martín-Llahí M, Fagundes C, Pereira G, Pavesi M, Fernández J, González-Abraldes J, Escorsell A, et al. Hyponatremia in patients treated with terlipressin for severe gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2010;52:1783–1790. doi: 10.1002/hep.23893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chiu KW, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. A controlled study of glypressin versus vasopressin in the control of bleeding from oesophageal varices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1990;5:549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1990.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Freeman JG, Cobden I, Record CO. Placebo-controlled trial of terlipressin (glypressin) in the management of acute variceal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:58–60. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198902000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.D’Amico G, Traina M, Vizzini G, Tinè F, Politi F, Montalbano L, Luca A, Pasta L, Pagliaro L, Morabito A. Terlipressin or vasopressin plus transdermal nitroglycerin in a treatment strategy for digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. A randomized clinical trial. Liver Study Group of V. Cervello Hospital. J Hepatol. 1994;20:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silvain C, Carpentier S, Sautereau D, Czernichow B, Métreau JM, Fort E, Ingrand P, Boyer J, Pillegand B, Doffël M. Terlipressin plus transdermal nitroglycerin vs. octreotide in the control of acute bleeding from esophageal varices: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 1993;18:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walker S, Kreichgauer HP, Bode JC. Terlipressin (glypressin) versus somatostatin in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices--final report of a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:692–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abraldes JG, Bosch J. Somatostatin and analogues in portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2002;35:1305–1312. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bagarani M, Albertini V, Anzà M, Barlattani A, Bracci F, Cucchiara G, Gizzonio D, Grassini G, Mari T, Procacciante F. Effect of somatostatin in controlling bleeding from esophageal varices. Ital J Surg Sci. 1987;17:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin HC, Yang YY, Hou MC, Huang YT, Lee WC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Hemodynamic effects of a combination of octreotide and terlipressin in patients with viral hepatitis related cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:482–487. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gotzsche PC. Somatostatin or octreotide for acute bleeding oesophageal varices. (Cochrane review) Oxford: Update Software; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joannon G, Doust J, Rockey DC. Terlipressin for acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage. (Cochrane review) Oxford: Update Software; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lo GH, Lai KH, Ng WW, Tam TN, Lee SD, Tsai YT, Lo KJ. Injection sclerotherapy preceded by esophageal tamponade versus immediate sclerotherapy in arresting active variceal bleeding: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:421–424. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moretó M, Zaballa M, Bernal A, Ibáñez S, Ojembarrena E, Rodriguez A. A randomized trial of tamponade or sclerotherapy as immediate treatment for bleeding esophageal varices. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:331–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paquet KJ, Feussner H. Endoscopic sclerosis and esophageal balloon tamponade in acute hemorrhage from esophagogastric varices: a prospective controlled randomized trial. Hepatology. 1985;5:580–583. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Stiegmann G, Goff JS. Endoscopic esophageal varix ligation: preliminary clinical experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laine L, el-Newihi HM, Migikovsky B, Sloane R, Garcia F. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Huang JS, Hsu PI, Chiang HT. Emergency banding ligation versus sclerotherapy for the control of active bleeding from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, Korula J, Lieberman D, Saeed ZA, Reveille RM, Sun JH, Lowenstein SR. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sengstaken RW, Blakemore AH. Balloon tamponage for the control of hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 1950;131:781–789. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195005000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Terés J, Cecilia A, Bordas JM, Rimola A, Bru C, Rodés J. Esophageal tamponade for bleeding varices. Controlled trial between the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube and the Linton-Nachlas tube. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:566–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Panés J, Terés J, Bosch J, Rodés J. Efficacy of balloon tamponade in treatment of bleeding gastric and esophageal varices. Results in 151 consecutive episodes. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:454–459. doi: 10.1007/BF01536031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cook D, Laine L. Indications, technique, and complications of balloon tamponade for variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. J Intensive Care Med. 1992;7:212–218. doi: 10.1177/088506669200700408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maufa F, Al-Kawas FH. Role of self-expandable metal stents in acute variceal bleeding. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:418369. doi: 10.1155/2012/418369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dechêne A, El Fouly AH, Bechmann LP, Jochum C, Saner FH, Gerken G, Canbay A. Acute management of refractory variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis by self-expanding metal stents. Digestion. 2012;85:185–191. doi: 10.1159/000335081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hubmann R, Bodlaj G, Czompo M, Benkö L, Pichler P, Al-Kathib S, Kiblböck P, Shamyieh A, Biesenbach G. The use of self-expanding metal stents to treat acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2006;38:896–901. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wright G, Lewis H, Hogan B, Burroughs A, Patch D, O’Beirne J. A self-expanding metal stent for complicated variceal hemorrhage: experience at a single center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W, Hubmann R. Results of a new method to stop acute bleeding from esophageal varices: implantation of a self-expanding stent. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2149–2152. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jalan R, Elton RA, Redhead DN, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. Analysis of prognostic variables in the prediction of mortality, shunt failure, variceal rebleeding and encephalopathy following the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol. 1995;23:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCormick PA, Dick R, Chin J, Irving JD, McIntyre N, Hobbs KE, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;49:791–793, 796-797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, Tisnado J, Cole PE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for patients with active variceal hemorrhage unresponsive to sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:138–146. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jalan R, Forrest EH, Stanley AJ, Redhead DN, Forbes J, Dillon JF, MacGilchrist AJ, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. A randomized trial comparing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt with variceal band ligation in the prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;26:1115–1122. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rössle M, Deibert P, Haag K, Ochs A, Olschewski M, Siegerstetter V, Hauenstein KH, Geiger R, Stiepak C, Keller W, et al. Randomised trial of transjugular-intrahepatic-portosystemic shunt versus endoscopy plus propranolol for prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 1997;349:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, DeMeo J, Cole PE, Tisnado J. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:889–898. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jabbour N, Zajko AB, Orons PD, Irish W, Bartoli F, Marsh WJ, Dodd GD, Aldreghitti L, Colangelo J, Rakela J, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with end-stage liver disease: results in 85 patients. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:139–147. doi: 10.1002/lt.500020210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Freedman AM, Sanyal AJ, Tisnado J, Cole PE, Shiffman ML, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Darcy MD, Posner MP. Complications of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: a comprehensive review. Radiographics. 1993;13:1185–1210. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.6.8290720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Purdum PP. TIPS-associated hemolysis and encephalopathy. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:443–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L, Bilbao JI, Bosch J, Rousseau H, Vinel JP. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469–475. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, Laleman W, Appenrodt B, Luca A, Abraldes JG, Nevens F, Vinel JP, Mössner J, Bosch J. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thabut D, Rudler M, Lebrec D. Early TIPS with covered stents in high-risk patients with cirrhosis presenting with variceal bleeding: are we ready to dive into the deep end of the pool? J Hepatol. 2011;55:1148–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rosemurgy AS, Goode SE, Zwiebel BR, Black TJ, Brady PG. A prospective trial of transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic stent shunts versus small-diameter prosthetic H-graft portacaval shunts in the treatment of bleeding varices. Ann Surg. 1996;224:378–384; discussion 384-386. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199609000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Terés J, Baroni R, Bordas JM, Visa J, Pera C, Rodés J. Randomized trial of portacaval shunt, stapling transection and endoscopic sclerotherapy in uncontrolled variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 1987;4:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bari K, Garcia-Tsao G. Treatment of portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1166–1175. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buchwalow IB, Podzuweit T, Bocker W, Samoilova VE, Thomas S, Wellner M, Baba HA, Robenek H, Schnekenburger J, Lerch MM. Vascular smooth muscle and nitric oxide synthase. FASEB J. 2002;16:500–508. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0842com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burroughs AK, Jenkins WJ, Sherlock S, Dunk A, Walt RP, Osuafor TO, Mackie S, Dick R. Controlled trial of propranolol for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1539–1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312223092502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Colombo M, de Franchis R, Tommasini M, Sangiovanni A, Dioguardi N. Beta-blockade prevents recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in well-compensated patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 1989;9:433–438. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Queuniet AM, Czernichow P, Lerebours E, Ducrotte P, Tranvouez JL, Colin R. Controlled study of propranolol in the prevention of recurrent hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1987;11:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rossi V, Calès P, Burtin P, Charneau J, Person B, Pujol P, Valentin S, D’Aubigny N, Joubaud F, Boyer J. Prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding in alcoholic cirrhotic patients: prospective controlled trial of propranolol and sclerotherapy. J Hepatol. 1991;12:283–289. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90828-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sheen IS, Chen TY, Liaw YF. Randomized controlled study of propranolol for prevention of recurrent esophageal varices bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Liver. 1989;9:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1989.tb00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Villeneuve JP, Pomier-Layrargues G, Infante-Rivard C, Willems B, Huet PM, Marleau D, Viallet A. Propranolol for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage: a controlled trial. Hepatology. 1986;6:1239–1243. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.García-Pagán JC, Feu F, Bosch J, Rodés J. Propranolol compared with propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. A randomized controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:869–873. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-10-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feu F, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Luca A, Terés J, Escorsell A, Rodés J. Relation between portal pressure response to pharmacotherapy and risk of recurrent variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Lancet. 1995;346:1056–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Patch D, Sabin CA, Goulis J, Gerunda G, Greenslade L, Merkel C, Burroughs AK. A randomized, controlled trial of medical therapy versus endoscopic ligation for the prevention of variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1013–1019. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Villanueva C, Balanzó J, Novella MT, Soriano G, Sáinz S, Torras X, Cussó X, Guarner C, Vilardell F. Nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate compared with sclerotherapy for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1624–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606203342502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sclerotherapy after first variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. A randomized multicenter trial. The Copenhagen Esophageal Varices Sclerotherapy Project. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1594–1600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412203112502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Korula J, Balart LA, Radvan G, Zweiban BE, Larson AW, Kao HW, Yamada S. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of chronic esophageal variceal sclerotherapy. Hepatology. 1985;5:584–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Westaby D, Macdougall BR, Williams R. Improved survival following injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices: final analysis of a controlled trial. Hepatology. 1985;5:827–830. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dasarathy S, Dwivedi M, Bhargava DK, Sundaram KR, Ramachandran K. A prospective randomized trial comparing repeated endoscopic sclerotherapy and propranolol in decompensated (Child class B and C) cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:89–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Westaby D, Polson RJ, Gimson AE, Hayes PC, Hayllar K, Williams R. A controlled trial of oral propranolol compared with injection sclerotherapy for the long-term management of variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1990;11:353–359. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dollet JM, Champigneulle B, Patris A, Bigard MA, Gaucher P. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus propranolol after hemorrhage caused by rupture of esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. Results of a 4-year randomized study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1988;12:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Martin T, Taupignon A, Lavignolle A, Perrin D, Le Bodic L. Prevention of recurrent hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Results of a controlled trial of propranolol versus endoscopic sclerotherapy. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1991;15:833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Terés J, Bosch J, Bordas JM, Garcia Pagán JC, Feu F, Cirera I, Rodés J. Propranolol versus sclerotherapy in preventing variceal rebleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1508–1514. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gimson AE, Ramage JK, Panos MZ, Hayllar K, Harrison PM, Williams R, Westaby D. Randomised trial of variceal banding ligation versus injection sclerotherapy for bleeding oesophageal varices. Lancet. 1993;342:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hashizume M, Ohta M, Ueno K, Tanoue K, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices compared with injection sclerotherapy: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hou MC, Lin HC, Kuo BI, Chen CH, Lee FY, Lee SD. Comparison of endoscopic variceal injection sclerotherapy and ligation for the treatment of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a prospective randomized trial. Hepatology. 1995;21:1517–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Hwu JH, Chang CF, Chen SM, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of sclerotherapy versus ligation in the management of bleeding esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1995;22:466–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Villanueva C, Miñana J, Ortiz J, Gallego A, Soriano G, Torras X, Sáinz S, Boadas J, Cussó X, Guarner C, et al. Endoscopic ligation compared with combined treatment with nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:647–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lo GH, Chen WC, Chen MH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Tsai WL, Lai KH. Banding ligation versus nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:728–734. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.de la Peña J, Brullet E, Sanchez-Hernández E, Rivero M, Vergara M, Martin-Lorente JL, Garcia Suárez C. Variceal ligation plus nadolol compared with ligation for prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding: a multicenter trial. Hepatology. 2005;41:572–578. doi: 10.1002/hep.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.García-Pagán JC, Villanueva C, Albillos A, Bañares R, Morillas R, Abraldes JG, Bosch J. Nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate alone or associated with band ligation in the prevention of recurrent bleeding: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2009;58:1144–1150. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.171207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kumar A, Jha SK, Sharma P, Dubey S, Tyagi P, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Addition of propranolol and isosorbide mononitrate to endoscopic variceal ligation does not reduce variceal rebleeding incidence. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:892–901, 901.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lo GH, Chen WC, Chan HH, Tsai WL, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Chen TA, Lai KH. A randomized, controlled trial of banding ligation plus drug therapy versus drug therapy alone in the prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:982–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Huang HC, Hsu PI, Lin CK. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:461–465. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cabrera J, Maynar M, Granados R, Gorriz E, Reyes R, Pulido-Duque JM, Rodriguez SanRoman JL, Guerra C, Kravetz D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus sclerotherapy in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:832–839. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cello JP, Ring EJ, Olcott EW, Koch J, Gordon R, Sandhu J, Morgan DR, Ostroff JW, Rockey DC, Bacchetti P, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy compared with percutaneous transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt after initial sclerotherapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.García-Villarreal L, Martínez-Lagares F, Sierra A, Guevara C, Marrero JM, Jiménez E, Monescillo A, Hernández-Cabrero T, Alonso JM, Fuentes R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of variceal rebleeding after recent variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1999;29:27–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Merli M, Salerno F, Riggio O, de Franchis R, Fiaccadori F, Meddi P, Primignani M, Pedretti G, Maggi A, Capocaccia L, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a randomized multicenter trial. Gruppo Italiano Studio TIPS (G.I.S.T.) Hepatology. 1998;27:48–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, Cole PE, Tisnado J, Simmons S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts compared with endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:849–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sauer P, Theilmann L, Stremmel W, Benz C, Richter GM, Stiehl A. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt versus sclerotherapy plus propranolol for variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1623–1631. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gülberg V, Schepke M, Geigenberger G, Holl J, Brensing KA, Waggershauser T, Reiser M, Schild HH, Sauerbruch T, Gerbes AL. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is not superior to endoscopic variceal band ligation for prevention of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:338–343. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Luca A, D’Amico G, La Galla R, Midiri M, Morabito A, Pagliaro L. TIPS for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiology. 1999;212:411–421. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.2.r99au46411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]