Abstract

Isolated metastases to the spleen from gastric carcinoma is very rare. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature. We herein present a case of isolated splenic metastases in a 62-year-old man, occurring 12 mo after total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. The patient underwent a laparoscopic exploration, during which two lesions were found at the upper pole of the spleen, without involvement of other organs. A laparoscopic splenectomy was performed. Histological examination confirmed that the splenic tumor was a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma similar to the primary gastric lesion. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient has been well for 9 mo, with no tumor recurrence. The clinical data of 18 cases of isolated splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma treated by splenectomy were summarized after a literature review. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of isolated splenic metastases undergoing laparoscopic splenectomy.

Keywords: Metastasis, Splenic neoplasms, Stomach neoplasms, Laparoscopy, Splenectomy

Core tip: Isolated metastases to the spleen from gastric carcinoma is very rare. We report a case of isolated splenic metastases in a 62-year-old man, occurring 12 mo after total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma who underwent laparoscopic splenectomy. The patient has been well for 9 mo after surgery with no tumor recurrence. The clinical data of 18 cases of isolated splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma treated by splenectomy were summarized after a literature review. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of isolated splenic metastases undergoing laparoscopic splenectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma are uncommon and are generally detected as part of multi-organ metastases. Isolated splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma are exceedingly rare with only a few cases having been documented in the literature. Here, we report a case of isolated splenic metastases, occurring 12 mo after eradication of gastric carcinoma, which was successfully treated by laparoscopic splenectomy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report documenting metachronous splenic metastases treated by laparoscopic surgery. In order to better understand the clinical behavior of isolated splenic metastases with gastric carcinoma origin, we reviewed a total of 18 such cases from the literature. The detailed features and prognoses of these cases were summarized in this study.

CASE REPORT

A 62-year-old man was diagnosed with gastric carcinoma located in the M and L portion of the stomach. The tumor was of ulcerative type in gross appearance (Borrmann III type) and was 9 cm × 8 cm in size. The patient underwent a total gastrectomy with a standard D2 lymph node dissection in February 2011. Histology of the resected specimen revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma infiltrating the serosa with nodal involvement (12 of 25 nodes were positive for metastases), fulfilling the criteria of stage IIIB according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging classification for carcinoma of the stomach (7th ed, 2012)[1]. The patient received six cycles of intravenous chemotherapy consisting of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin after surgery. Ultrasonography and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan did not reveal any remarkable metastatic lesions during the postoperative follow-up.

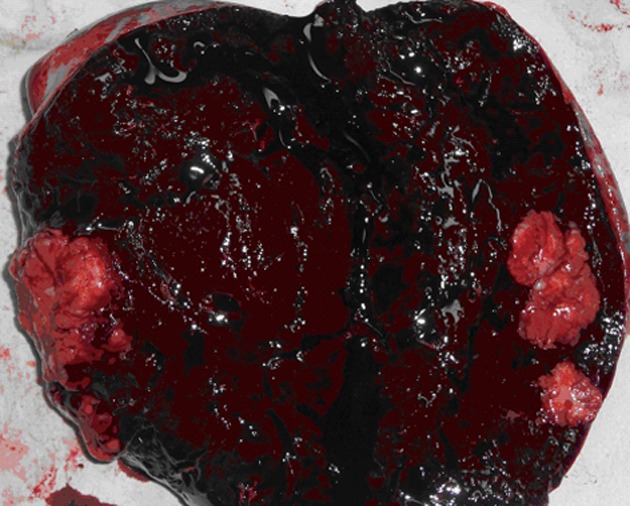

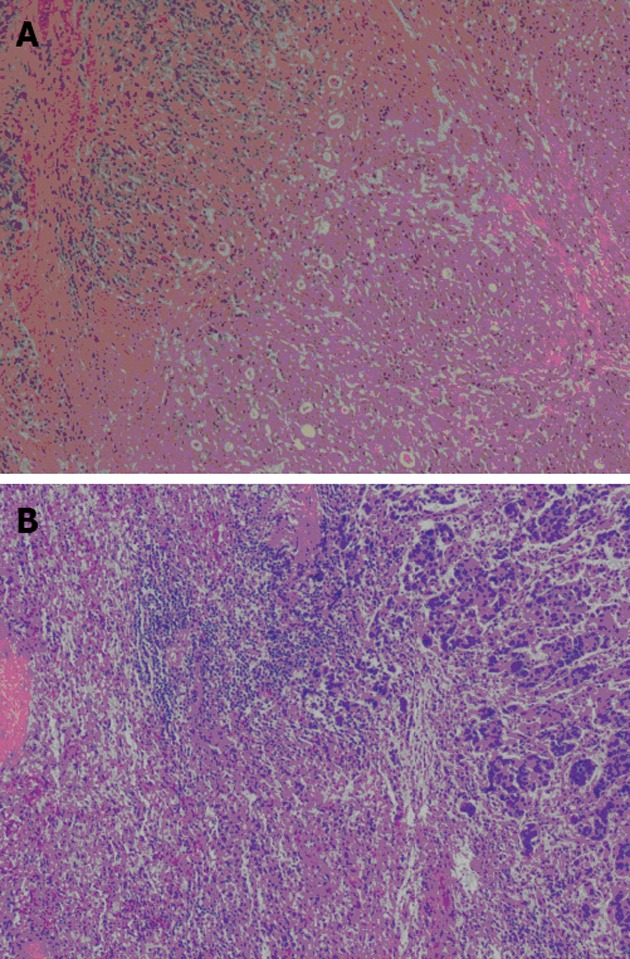

In February 2012, an abdominal CT scan showed two low-density lesions, 4.5 cm × 3.5 cm and 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm, respectively, at the upper pole of the spleen without obvious contrast enhancement (Figure 1). Two hypoechoic lesions in the corresponding location of the spleen were revealed by ultrasonography. The previous history of gastric carcinoma contributed to a presumptive diagnosis of metachronous splenic metastases. The patient was given two cycles of chemotherapy consisting of intravenous 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin. A thorough diagnostic workup, including gastroscopy, CT scan of chest and abdomen, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography scan, was negative for extra-splenic tumor dissemination. However, ultrasound as well as CT scan revealed enlargement of the splenic lesions which indicated their poor responsiveness to the chemotherapeutics. The patient underwent a laparoscopic exploration since his splenic metastases were revealed to be isolated and resectable. The splenic lesions were confirmed during the procedure, while no other intra-abdominal organ metastasis or peritoneal dissemination was seen. A laparoscopic splenectomy was performed in April 2012. The specimen showed two lesions, measuring 4.5 cm × 4.0 cm and 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm respectively, occupying the upper pole of the spleen. The tumors were yellowish-white in color, which demarcated them quite clearly from the adjacent splenic parenchyma, and showed no bleeding or necrosis (Figure 2). Histological examination showed that the lesions were metastatic adenocarcinoma consistent with the features of the primary gastric carcinoma (Figure 3) with no lymph node involvement at the splenic hilum.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed two low-density lesions (arrows), 4.5 cm × 3.5 cm and 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm in size respectively, at the upper pole of the spleen.

Figure 2.

Cross section of the spleen showing two yellowish-white lesions at the upper pole.

Figure 3.

Histological findings of the primary gastric carcinoma (A) and the splenic metastatic tumor (B) (hematoxylin-eosin stain, × 40).

The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged eight days after surgery. He recovered well and showed no evidence of tumor recurrence at the last follow-up in December 2012.

DISCUSSION

Splenic metastases from non-hematologic malignancies are infrequent, with an incidence of 0.6%-1.1% in populations with carcinoma according to a large clinicopathologic study[2]. The rarity of splenic metastases might be explained by the following reasons: (1) the poorly developed lymphoid system of the spleen, especially the lack of afferent lymphatic vessels, prevents the spleen from receiving metastatic tumor cells via the lymphatic route; (2) the sharp angle of splenic artery branching from the celiac trunk inhibits large clumps of tumor cells from passing through; and (3) the microenvironment of the spleen may hinder the growth of micrometastatic foci[3].

Most splenic metastases are accompanied by multivisceral tumor dissemination. Skin melanoma and carcinomas of the breast, lung, ovary, colorectum and stomach are the major primary sources of splenic metastases, and gastric carcinoma accounts for 6.9%[2]. Very few splenic metastases occur as isolated splenic lesions, synchronous or metachronous to the primary tumor. To our knowledge, only seven cases of synchronous splenic metastases and 11 cases of metachronous splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma have been treated by splenectomy to date. A summary of these cases is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patients with isolated splenic metastasis from gastric carcinoma treated by splenectomy

| No. | Source | Gender/age (yr) |

Primary gastric carcinoma |

Splenic metastasis |

CT appearance | Survival time (mo)/status/tumor dissemination | |||

| Location1 | Histology2 | Interval3(mo) | Other involvement | Suggested route | |||||

| 1 | Takebayashi et al[10] | F/64 | U, M | Por, T3, n1, M1 | 0 | LNs | Lymphatic | NS | 3/dead/lung |

| 2 | Fujita et al[11] | F/75 | R | Tub, T4, n3, M1 | 0 | LNs | Hematogenous | NS | NS |

| 3 | Mori et al[12] | M/49 | R | Tub, T3, n3, M1 | 0 | LNs | Hematogenous | NS | 12/alive/NS |

| 4 | Okuno et al[13] | M/56 | U, M | Por, T3, n2, M1 | 0 | LNs and peritoneum | Lymphatic | NS | 1/dead/peritoneum, bone, pancreas, adrenal, liver |

| 5 | Sakamoto et al[14] | M/67 | U, M | Tub, T4, n2, M1 | 0 | LNs | Hematogenous | NS | 8/dead/liver |

| 6 | Ishida et al[15] | M/65 | U | Por, T2, n2, M1 | 0 | LNs | NS | NS | 5/dead/tumor embolism of portal vein |

| 7 | Lu et al[16] | M/59 | U | Hepatoid AC, T4 | 0 | LNs | NS | Heterogenous low-density lesions | 18/alive/liver |

| 8 | Ikeda et al[17] | M/57 | U | Por, T3, n1, M0 | 17 | None | NS | NS | 15/alive/ NS |

| 9 | Shirai et al[18] | M/63 | M | Pap, T1, n0, M0 | 33 | None | Hematogenous | NS | 20/alive/ NS |

| 10 | Tatsusawa et al[19] | M/54 | M | Tub, T2, n2, M0 | 102 | None | Hematogenous | NS | NS |

| 11 | Takahashi et al[20] | M/64 | L | Tub, T2, n3, M0 | 16 | None | Hematogenous | NS | 7/dead/liver, lung |

| 12 | Opocher et al[4] | F/76 | L | Tub, T2, N0, M0 | 57 | None | Hematogenous | Round cystic area with fluid content | 13/alive/none |

| 13 | Opocher et al[4] | M/66 | NS | Por, T2, N1, M0 | 36 | None | Hematogenous | NS | 14/alive/none |

| 14 | Williams et al[5] | M/69 | U | AC | 43 | None | NS | Soft tissue mass with cacification | NS |

| 15 | Yamanouchi et al[8] | M/69 | L | Tub, T2, N1, M0 | 48 | None | Hematogenous? | Low-density area | 40/dead/liver, peritoneum |

| 16 | Sunitsch et al[21] | F/80 | L, R | Por, T1, N0, M0; | 37 | None | NS | NS | NS |

| tp, T1, N0, M0 | |||||||||

| 17 | Kawasaki et al[22] | M/76 | U | Pap, T1, N1, M0 | 12 | None | Hematogenous? | Low-density lesion | 24/alive/none |

| 18 | Zhou et al[23] | M/76 | U | Tub | 36 | None | NS | NS | 30/alive/none |

U, M, and L: Indicate the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the stomach, respectively; R: Residual stomach;

Por: Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; tub: Tubular adenocarcinoma; pap: Papillary adenocarcinoma; tp: Tubulopapillary adenocarcinoma; AC: Adenocarcinoma; T1: Tumor invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae or submucosa; T2: Tumor invades muscularis propria; T3: Tumor penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures; T4: Tumor invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) or adjacent structures[1]; n: n0 indicates no evidence of lymph node metastasis; n1, n2, and n3 indicate metastasis to the groups 1, 2, and 3 lymph nodes, respectively, according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[24]; N: N0: No regional lymph node metastasis; N1, N2 and N3 indicate metastasis in 1-2, 3-6, 7 or more regional lymph nodes; M: M0: No distant metastasis; M1: Distant metastasis;

Interval: Interval from the detection of primary gastric carcinoma to the detection of the splenic secondary tumor. 0 indicates the the splenic secondary tumor detected at the same time as the primary tumor. LNs: Lymph nodes; CT: Computed tomography; NS: Not specified.

Isolated splenic metastases are often first identified by ultrasonography or CT scan as most of them are asymptomatic. However, some patients harboring splenic metastases complain of fatigue, weight loss, fever, abdominal pain, splenomegaly, anemia, or thrombocytopenia[3]. Generally, when an isolated splenic lesion is found during the oncologic follow-up, a metastatic origin should be suspected. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 have been reported to be of predictive value in detecting the appearance of isolated splenic metastases in advance of imaging identification[4]. In our review, the splenic metastases presented variously on CT scan, and ranged from a cystic lesion, low-density occupying lesion to a solid mass, and showed different patterns of enhancement. A calcified splenic mass, which is a common feature of metastases from primary mucinous adenocarcinoma, was also described[5]. In this regard, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the suspected splenic metastases from primary splenic lesions such as lymphoma, vascular tumor, or infectious disorder. It has been reported that 18F-FDG positron emission tomography was of value in distinguishing benign from malignant masses of the spleen[6]. As a highly vascular organ, the spleen is often considered an inappropriate target for fine-needle aspiration (FNA) due to the potential risk of bleeding. Nevertheless, Cavanna et al[7] reported a series of 160 patients who underwent biopsy of the splenic mass by FNA with an overall accuracy rate of 98.1% and with no complications, which demonstrated that the technique is safe and effective.

In the present case, two masses were detected in the spleen by imaging techniques 12 mo after a radical gastrectomy. The previous history of gastric carcinoma indicated the diagnosis of a splenic metastasis which was subsequently supported by an 18F-FDG positron emission tomography scan. Ultimately, the pathological study of the surgical specimen, which showed a papillary adenocarcinoma with a high morphological resemblance to the primary gastric carcinoma, confirmed our clinical diagnosis.

Gastric carcinoma in the U or M portion is likely to invade the spleen directly because of their anatomical contiguity. In such cases, the metastatic lesions are always detected synchronously or very shortly after a radical gastrectomy. In contrast, splenic metastases are often detected later when they are caused by the hematogenous route. In our literature review, the mean time from the diagnosis of primary stomach carcinoma to the development of secondary splenic metastases was 39.7 mo with the longest time being 102 mo[8]. The late occurrence of blood-borne isolated splenic metastases could be explained by some recent advances in the knowledge of the metastatic mechanism: it may develop from an early micro-metastasis within the spleen and progress to an observable lesion after a period of clinical latency[9]. We also noted that the mean duration from the detection of the primary gastric tumor to the detection of the splenic secondary tumor was shorter in Lam and Tang’s review (3-36 mo, mean 8 mo)[2]. We speculate that there might have been a proportion of the splenic metastases in their analysis which were caused by direct invasion from primary gastric tumors, whereas there was not a single case in our review which was reported to be caused by direct invasion. This might explain the time difference between the two reviews.

As isolated splenic metastases from gastric carcinoma are rarely documented in the literature, it is still difficult to predict the clinical behavior of this disease. However, the existing preliminary records show a tendency that long-term remission could be expected after splenectomy in a metachronous splenic metastasis, while a synchronous splenic metastasis always indicates early tumor progression and a worse outcome. In our review, patients with gastric carcinoma and synchronous splenic metastases had a mean post-operative survival time of seven months, apparently shorter than that of the patients with metachronous splenic metastases (mean 20.3 mo after splenectomy).

Although splenectomy provides a possible means of radical treatment in patients with isolated splenic metastases, it should be decided with caution as a splenic metastatic lesion which is supposed to be “isolated” sometimes may represent an initial clinical manifestation of systemic metastases at multiple sites. Under such circumstances, surgical stress from splenectomy might cause adverse clinical effects in the patient. With this in mind, following the discovery of the splenic lesions in the present patient, rather than performing splenectomy immediately, he was given two cycles of chemotherapy and this time span was used for observation as well. As no new metastatic lesions emerged, a laparoscopic exploration and splenectomy was performed.

As a result of previous surgery, there was severe adhesion in the upper quadrant of the abdomen, especially between the transverse colon and the spleen, which needed careful separation. Conversely, the isolation of the splenic pedicle was not as difficult, as the connective tissue in this region had been removed and all the short gastric vessels had been severed during the previous operation of total gastrectomy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report documenting metachronous splenic metastases treated by laparoscopic surgery. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and he has been well with no evidence of tumor recurrence for nine months.

According to our experience, laparoscopic splenectomy seems to be a promising approach in achieving long-term survival in patients with metachronous isolated splenic metastases after eradication of gastric carcinoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Harsha Ajoodhea (Zhejiang University School of Medicine) for improving the English language of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by The Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province, No. 2011C3036-2; and the Health Bureau of Zhejiang Province, No. 2011ZHB003

P- Reviewer Abdou AG S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam KY, Tang V. Metastatic tumors to the spleen: a 25-year clinicopathologic study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:526–530. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0526-MTTTS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compérat E, Bardier-Dupas A, Camparo P, Capron F, Charlotte F. Splenic metastases: clinicopathologic presentation, differential diagnosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:965–969. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-965-SMCPDD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Opocher E, Santambrogio R, Bianchi P, Cioffi U, De Simone M, Vellini S, Montorsi M. Isolated splenic metastasis from gastric carcinoma: value of CEA and CA 19-9 in early diagnosis: report of two cases. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:579–580. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200012000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams L, Kumar A, Aggarwal S. Calcified splenic metastasis from gastric carcinoma. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:312–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00203360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metser U, Miller E, Kessler A, Lerman H, Lievshitz G, Oren R, Even-Sapir E. Solid splenic masses: evaluation with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanna L, Lazzaro A, Vallisa D, Civardi G, Artioli F. Role of image-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the management of patients with splenic metastasis. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanouchi K, Ikematsu Y, Waki S, Kida H, Nishiwaki Y, Gotoh K, Ozawa T, Uchimura M. Solitary splenic metastasis from gastric cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:1081–1084. doi: 10.1007/s005950200218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodison S, Kawai K, Hihara J, Jiang P, Yang M, Urquidi V, Hoffman RM, Tarin D. Prolonged dormancy and site-specific growth potential of cancer cells spontaneously disseminated from nonmetastatic breast tumors as revealed by labeling with green fluorescent protein. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3808–3814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takebayashi M, Yurugi E, Okamoto T, Nishidoi H, Tamura H, Kaibara N. Metastasis of gastric cancer to the spleen--a case report. Gan No Rinsho. 1983;29:1703–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita M, Yamazaki S, Morioka G, Machida J, Ochiai K, Ozawa M, Ohtsuki H, Shimoyama N, Ishidate T. A rare case of metastasis of the spleen from recurrent cancer of the residual stomach. Gan No Rinsho. 1989;35:855–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori T, Seike Y, Nishimura T, Nakai H, Goto M. A case of the residual stomach metastasizing to the spleen. Nippon Rinshou Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;54:1044–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuno S, Souda S, Yoshikawa Y, Sawai T, Nakajima K, Kurihara Y, Ohshima M. A case report of gastric cancer with splenic metastasis. Nisseibyouin Igaku Zasshi. 1994;22:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto Y, Ogawa A, Hidaka K, Miyazaki K. A case of advanced cancer with splenic metastasis diagnosed preoperatively. Syoukakigeka. 1998;21:1265–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida H, Tatsuta M, Kawasaki T, Masutani S, Miya A, Baba M, Shiozaki K, Tsuji Y, Morimoto O, Yoshioka H, et al. A resected case of gastric cancer with splenic metastasis. Syoukakigeka. 1998;21:361–365. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu CC, De-Chuan C, Lee HS, Chu HC. Pure hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach with spleen and lymph-node metastases. Am J Surg. 2010;199:e42–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda H, Seto Y, Oyamada K, Hatakeyama S. A case of solitary splenic metastasis following total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Hiroshima Igaku Zasshi. 1989;42:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirai S, Igarashi T, Watanabe K, Kohno F, Hayashi T, Yoshida K. A case of surgical treatment of solitary splenic metastasis after a curative resection of early gastric cancer. Nippon Rinshou Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;53:3012–3016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatsusawa Y, Tawaraya K, Fujioka S, Yamada T, Kitagawa S, Nakagawa M. A case of gastric cancer solitarily metastasizing to the spleen eight years after operation. Nippon Rinshou Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;58:2425–2428. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi Y, Hasegawa H, Ogiso S, Shiomi M, Momiyama M, Taihei S. A resected case of metachronous solitary splenic metastasis following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Rinshou Geka. 1999;54:797–800. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunitsch S, Eberl T, Jagoditsch M, Filipot U, Tschmelitsch J, Langner C. Solitary giant splenic metastasis in a patient with metachronous gastric cancers. South Med J. 2009;102:864–866. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ac1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki H, Kitayama J, Ishigami H, Hidemura A, Kaisaki S, Nagawa H. Solitary splenic metastasis from early gastric cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:60–63. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J, Liang P, Yu X, Wang Y, Gao Y. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation of splenic metastasis: report of four cases and literature review. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27:517–522. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2011.563768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Japanese Gastric Cancer A. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]