Abstract

Imaging of the anterior male urethra has traditionally been performed by fluoroscopic contrast urethrography. While providing easily interpretable images, this technique has a number of disadvantages associated with it. An alternative approach is to use ultrasound to assess the lumen of the urethra and the periurethral tissues. Here we describe the development of urethral ultrasound and the ascending and descending urethral ultrasound techniques employed in our institution with reference to commonly and uncommonly encountered pathologies. We also identify common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

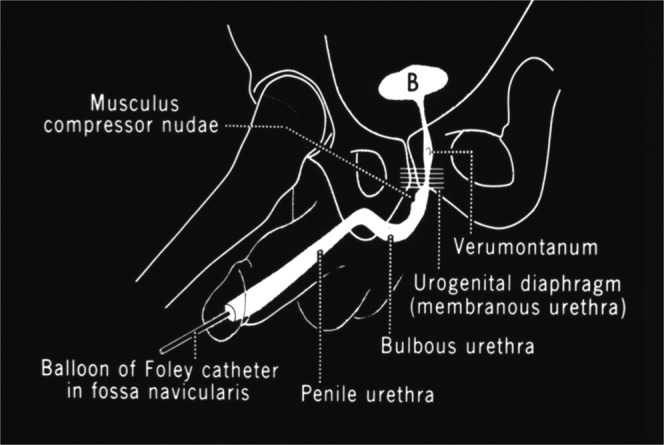

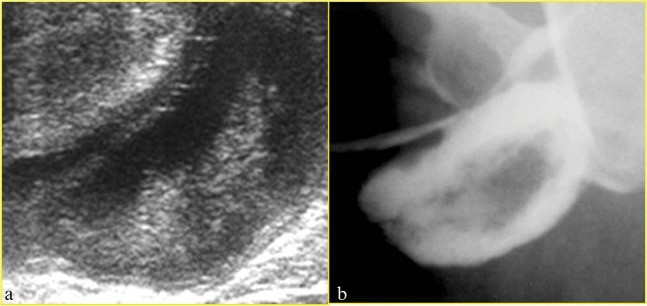

The primary imaging modality for demonstrating the male anterior urethra is fluoroscopic contrast urethrography performed either as a retrograde study via catheter insertion into the distal urethra [1] (Figure 1) or as a voiding study to delineate the posterior urethra. The retrograde technique requires gentle inflation of the catheter balloon within the navicular fossa of the distal urethra to enable gentle traction so that the anterior urethra can be straightened and to prevent leakage of the contrast medium around the catheter.

Figure 1.

Anatomy and technique of retrograde contrast urethrography [1].

The main advantages of the technique are that it has a high sensitivity for the detection of urethral strictures and that the images obtained are easy to interpret for the non-radiologist. However, there are a number of disadvantages, including the fact that it may not be possible to catheterise the distal urethra, particularly in patients with meatal stenosis or previous surgery. Also, the technique is necessarily invasive, and interpretation may be hampered by the presence of air bubbles, which may obscure pathology or even provide a false-positive study. In addition, as the balloon of the catheter is inflated in the distal urethra, pathology in this area will not be identified. Urethral ultrasound has not been widely adopted, and is a routine procedure in few centres, yet it addresses several of the shortcomings of the contrast technique.

Development of urethral ultrasound

The initial experiences with ultrasound evaluation of the urethra were described separately in the late 1980s by McAninch et al [2] and Merkle and Wagner [3].

Early studies identified not only the ability of ultrasound to demonstrate the exact length of strictures but also the added ability to define the periurethral tissues, as opposed to contrast urethrography, which only demonstrates the lumen. In particular, the presence and degree of periurethral fibrosis can be shown with a view to guiding surgery [4,5].

This was in addition to the obvious advantages of relative non-invasiveness, ready availability and lack of ionising radiation exposure. In terms of comparison between the two methods in assessing stricture disease, a number of studies have demonstrated that ultrasound is at least as effective as contrast urethrography in assessing length and extent of stricture [6-10] and indeed may be superior, particularly in the evaluation of short strictures [11,12] and strictures situated within the bulbar urethra [13,14]. Recent advances in ultrasonographic techniques (such as extended-field-of-view imaging) further add to the utility of the technique, and are particularly useful in demonstrating pathology to non-radiologists [15] at clinic radiological meetings.

Ascending urethral ultrasound technique

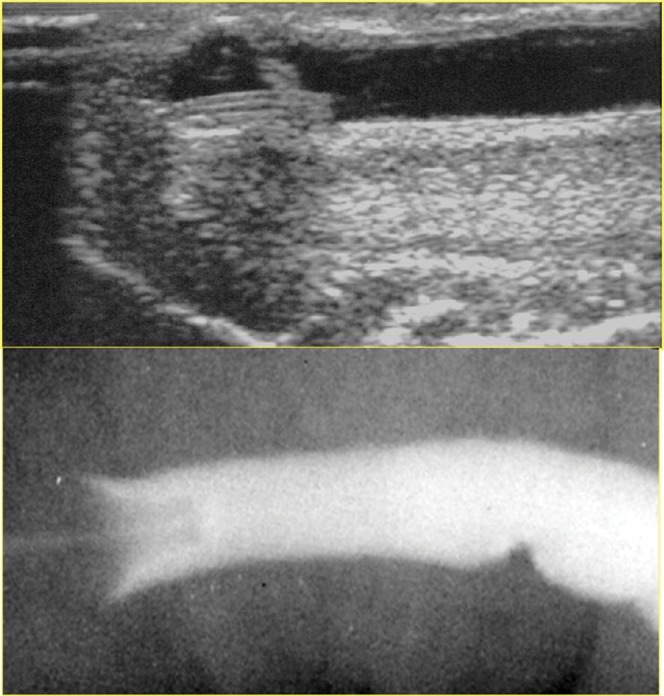

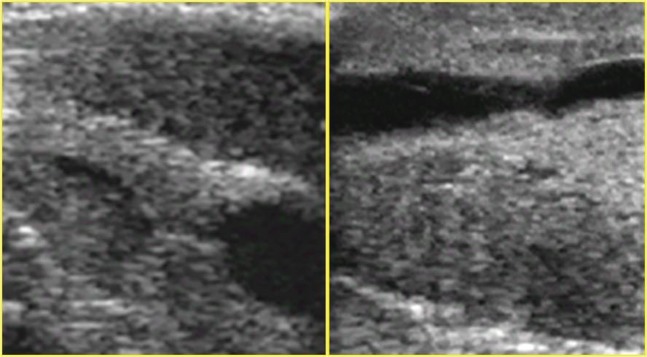

Our initial institutional experience [16] employed an ascending ultrasound technique whereby a catheter was placed distally in a similar manner to contrast urethrography with a balloon inflated in the fossa navicularis and the urethra distended with either saline or, if a conventional urethrogram was also required, contrast medium. Ultrasound was performed using a high-frequency linear array transducer with direct skin contact along the ventral surface of the penis. Subscrotal and perineal views were obtained. The images obtained were inverted so as to facilitate comparison with the more familiar contrast urethrograms (Figure 2). Acoustic shadowing from the very distal tip of the catheter beyond the balloon was found to obscure pathology in the distal urethra, therefore the catheter tip was trimmed to avoid this pitfall (Figure 3).

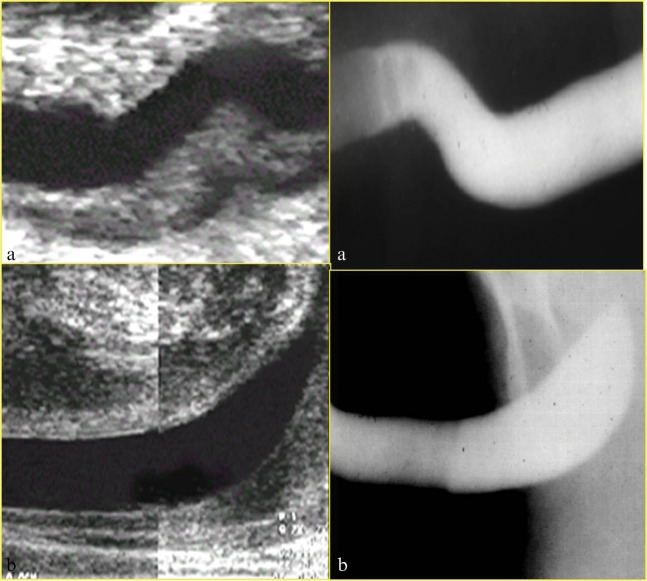

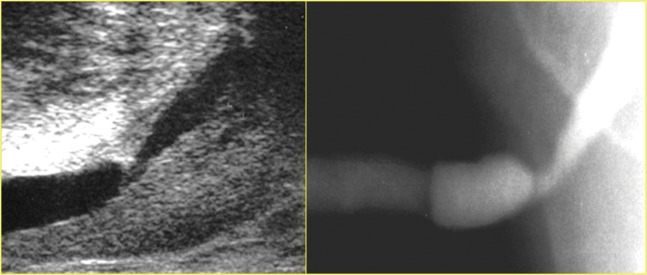

Figure 2.

Demonstration of comparative ultrasound (top) and contrast urethrography (bottom) images of the distal urethra.

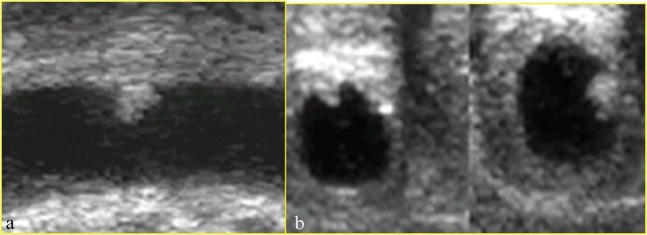

Figure 3.

(a) Posterior acoustic shadowing behind the tip of the catheter obscuring the distal urethra. (b) Better demonstration of the distal urethra following trimming of the distal catheter beyond the balloon.

Using this technique, it is possible to demonstrate the anatomy of the normal anterior urethra clearly in longitudinal (Figure 4) and transverse (Figure 5) scanning planes. The transverse section images are particularly welcomed by urologists who are able to relate the image to the view obtained at urethroscopy. Strictures (Figure 6) become clearly visible and can be evaluated in terms of length and degree of narrowing. Mucosal abnormalities that may appear as subtle filling defects on contrast urethrogram that could easily be overlooked can be seen on ultrasound and characterised further. Figure 7 shows a filling defect within the distal urethra on urethrogram, with the typical appearances of a viral papilloma. This was interpreted as a bubble on the accompanying contrast study. Missing such an abnormality, particularly in patients who are not responding to standard treatments, could have significant clinical consequences. Other mucosal abnormalities such as mucosal tags (Figure 8) and other luminal abnormalities such as diverticula of the anterior urethra (Figure 9) are also well demonstrated.

Figure 4.

Comparison of normal urethral anatomy as seen on ultrasound (left) and contrast urethrography (right). (a) Normal peno-scrotal junction and (b) normal bulbar urethra.

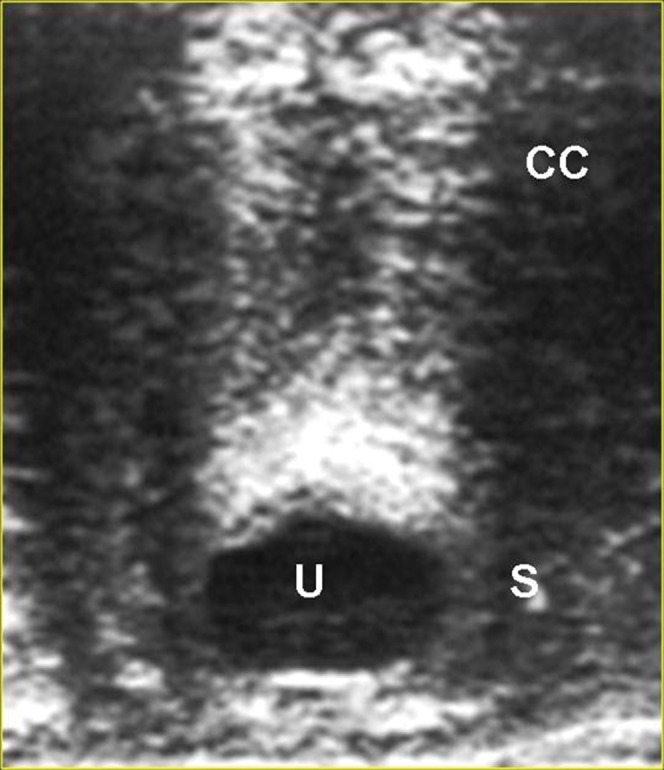

Figure 5.

Normal urethra in transverse section. CC, corpus cavernosum; S, spongiosum surrounding urethra; U, urethral lumen.

Figure 6.

Bulbar stricture on ultrasound (left) and urethrography (right).

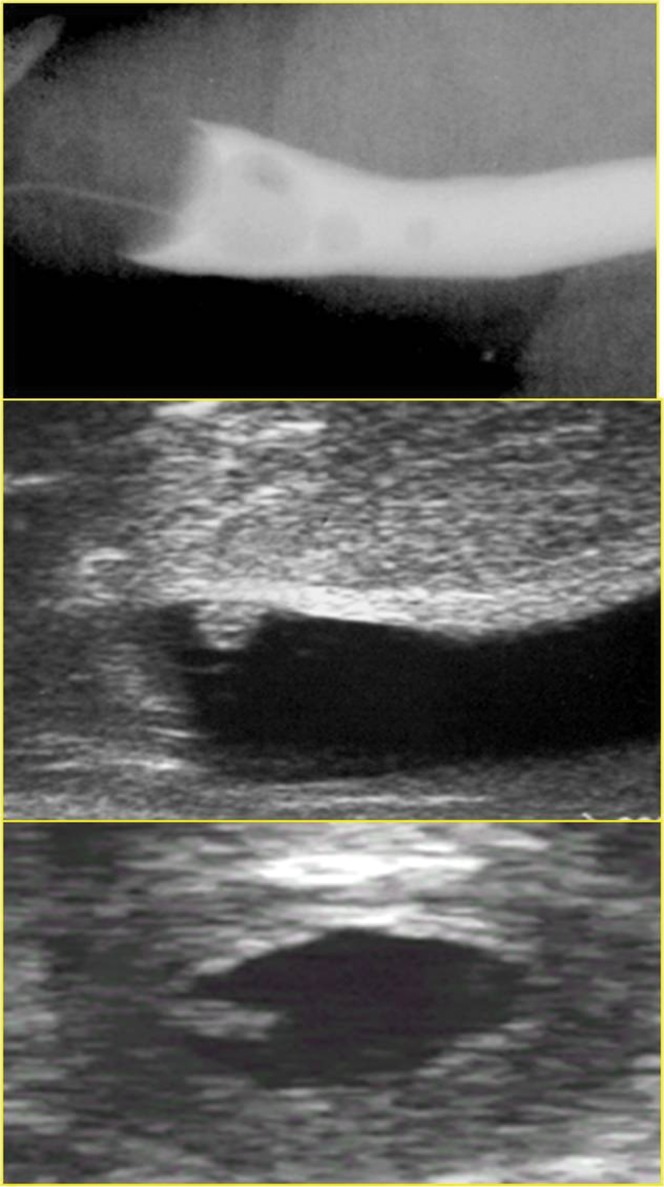

Figure 7.

The viral papilloma demonstrated on the ultrasound study (middle and bottom) was overlooked as a bubble on the contrast urethrogram (top).

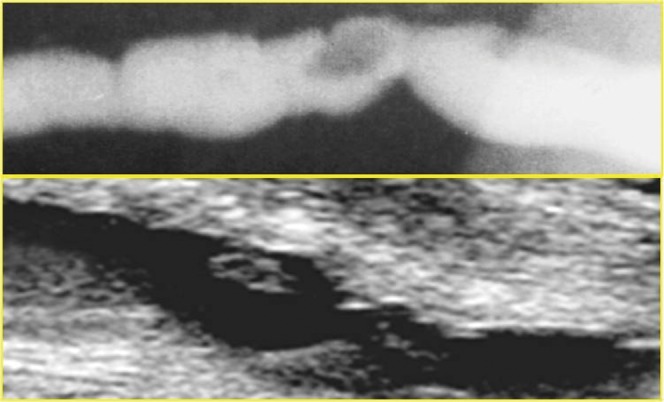

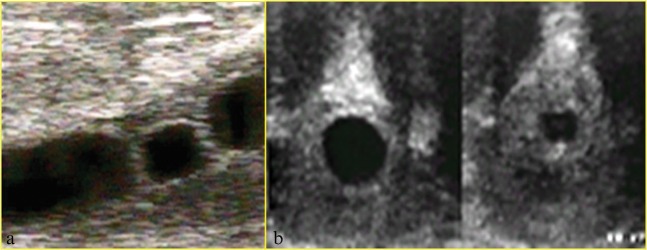

Figure 8.

Mucosal tag seen as filling defect on urethrography (top) and ultrasound (bottom).

Figure 9.

(a) Urethral diverticulum seen on ultrasound with layering of debris within it and (b) urethrogram correlate.

Some of the disadvantages associated with retrograde urethrography also apply to ascending urethral ultrasonography. The technique remains invasive, with insertion of a catheter distally, and requires two operators (one to instil fluid to distend the urethra and ensure no displacement of the catheter, and the second to perform the ultrasound). Furthermore, despite trimming of the distal catheter beyond the balloon to allow visualisation of the penile urethra, pathology in the fossa navicularis cannot be identified owing to the presence of the balloon. The procedure also requires a sterile technique.

Descending urethral ultrasound technique

In our institution the ascending technique has been superseded by a descending approach [17]. The technique once again involves transverse and sagittal views of the urethra using a high-frequency linear array probe. The patient attends with a full bladder and voids into a receptacle. Urethral distension is achieved with the urine stream, which is interrupted by the patient gently clamping the penis between thumb and forefinger during voiding, approximately 2 cm proximal to the tip after retraction of the foreskin. If needed in selected patients, views of the navicular fossa are obtained while actively voiding (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Normal navicular fossa seen during voiding descending urethral ultrasound (left), with diagrammatic representation of navicular fossa (right).

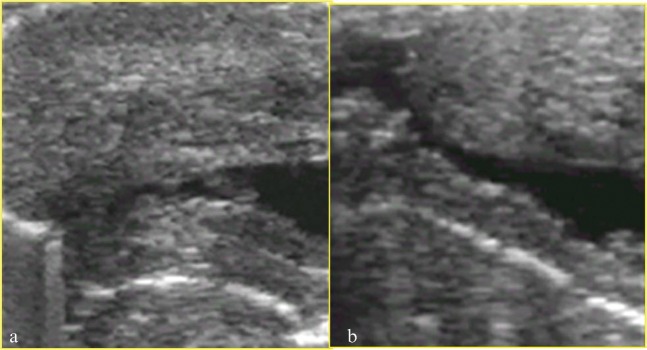

With this method the same range of pathologies seen using the ascending method can be identified, such as strictures (Figure 11), intraluminal structures such as papillomas (Figure 12) and periurethral fibrotic cuffing (Figure 13). In addition, the ability to visualise the navicular fossa allows pathology such as strictures in this region (Figure 14) to be visualised.

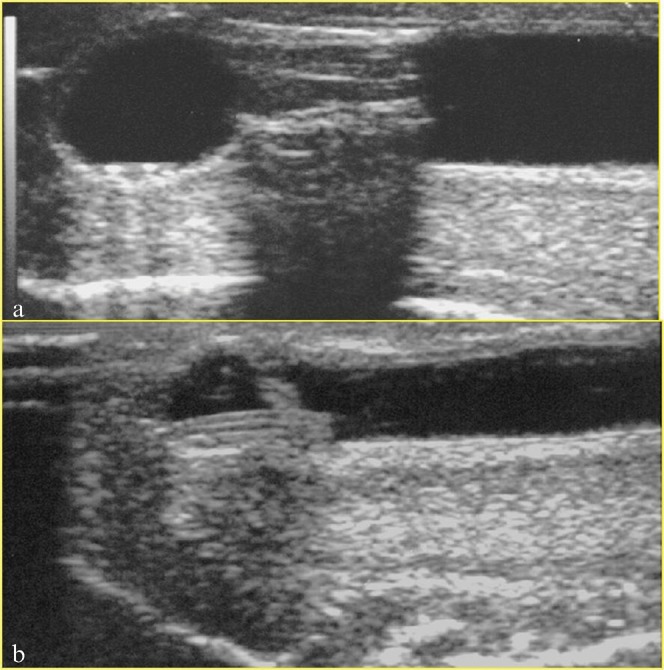

Figure 11.

Urethral stricture seen using the descending ultrasound technique in (a) longitudinal and (b) transverse planes.

Figure 12.

Viral papilloma seen in (a) longitudinal and (b) transverse planes.

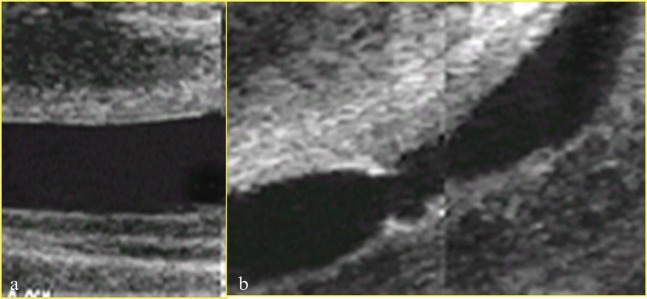

Figure 13.

(a) Normal mucosa and periurethral tissues. (b) Periurethral fibrotic cuffing surrounding bulbar stricture.

Figure 14.

Two examples of strictures within the fossa navicularis that could not be demonstrated on either contrast urethrography or ascending urethral ultrasound. The penile tip is to the left of the images.

A further area in which we have found descending urethral ultrasound to be invaluable is in those patients who have had or are planning to undergo hypospadias repair [18]. The condition itself is associated with other abnormalities such as urethral strictures [19], and following repair there is an increased likelihood of post-surgical stricturing. Depending on the severity of the disease, it may be completely impossible to employ either contrast urethrography or ascending ultrasound technique owing to an inability to catheterise the meatus, or undesirable in terms of requiring bladder catheterisation prior to acquiring a micturating urethrogram. The radiation burden to the gonads is a consideration, particularly as many of these patients will be children or young adults. In our experience, young patients generally tolerate the procedure well and we have been able to perform the technique in children as young as 4 years of age (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Descending urethral ultrasound in hypospadias assessment demonstrating (a) a pinhole ventrally placed meatus and (b) a distal post-operative irregularity. The penile tip is to the left of the images.

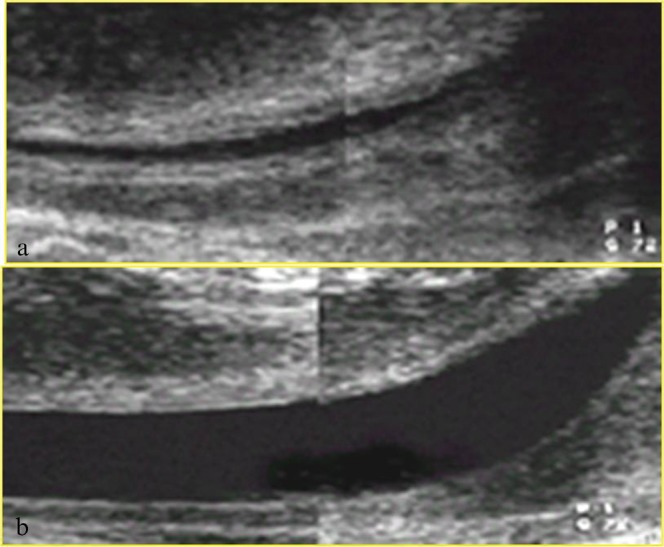

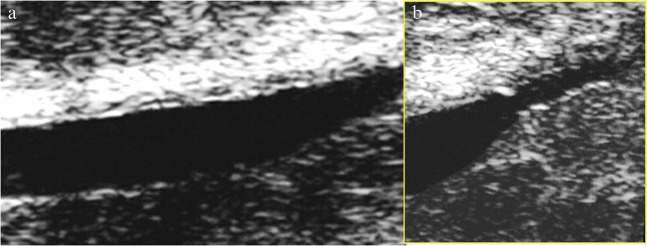

In summary, the advantages of the descending ultrasound technique over the alternative imaging methods are that it is non-invasive, is well-tolerated by the patient, can be performed by a single operator and provides excellent views of the distal urethra, which is especially important in hypospadias assessment. The operator should be aware of several pitfalls. Underdistension by an inadequate stream of urine can mimic a long stricture (Figure 16). A further potential pitfall to be aware of is the fact that care needs to be taken to avoid missing very proximal bulbar strictures. It may be necessary in such cases to perform further voiding views via a perineal approach (Figure 17).

Figure 16.

Two attempts at performing descending urethral ultrasound in the same patient. (a) At the first attempt there was insufficient distension of the urethra. (b) This was rectified at the second attempt.

Figure 17.

(a) Descending urethral ultrasound that fails to demonstrate a proximal stricture, which is identified on (b) perineal voiding images.

Discussion

In approximately 25 years since the early descriptions of urethral ultrasound were published the technique has developed from a semi-invasive ascending urethral technique to a non-invasive, cheap and easily performed procedure. It is at least as effective as contrast urethrography in the assessment of strictures, and may be more accurate in assessing short strictures and abnormalities in the bulbar urethra. It also enables assessment of the periurethral tissues.

Urethral ultrasound has been described in the presentation of trauma [20], but is yet to be widely adopted, possibly because of the unavailability of an experienced operator in the acute setting. It also has the potential to be invaluable in surgical planning, as a recent study by Buckley et al [21] demonstrates, where ultrasonography of the urethra was shown to directly influence the reconstructive operative approach for anterior urethroplasty in 45% of cases. It is regrettable that the technique is not more widely employed. This may be owing to a general lack of awareness of the facility and utility of the technique among urologists [22].

The technique has the further advantage over contrast urethrography of providing no radiation burden to the gonads, particularly in the paediatric population, whether this be stricture disease in the adolescent child [23] or in the context of hypospadias. The main limitations relate to proximal strictures, the requirement for a co-operative and co-ordinated patient and the need to be aware of the potential for false positives due to underdistension of the urethra. In conclusion, urethral ultrasound is an inexpensive and effective technique for imaging the anterior urethra, and indeed in some cases may be the only method of doing so.

References

- 1.McCallum RW. The adult male urethra: normal anatomy, pathology, and method of urethrography. Radiol Clin North Am 1979;17:227–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAninch JW, Laing FC, Jeffrey Jr RB. 226. Sonourethrography in the evaluation of urethral strictures: a preliminary report. J Urol 1988;139:294–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merkle W, Wagner W. Sonography of the distal male urethra—a new diagnostic procedure for urethral strictures: results of a retrospective study. J Urol 1988;140:1409–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klosterman PW, Laing FC, McAninch JW. Sonourethrography in the evaluation of urethral stricture disease. Urol Clin North Am 1989;16:791–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiou RK, Anderson JC, Tran T, Patterson RH, Wobig R, Taylor RJ. Evaluation of urethral strictures and associated abnormalities using high-resolution and color Doppler ultrasound. Urology 1996;47:102–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das S. Ultrasonographic evaluation of urethral stricture disease. Urology 1992;40:237–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arda K, Basar M, Deniz E, Yildiz S, Akpìnar L, Olçer T. Sonourethrography in anterior urethral stricture: comparison to radiographic urethrography. Arch Ital Urol Androl 1995;67:249–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhary S, Singh P, Sundar E, Kumar S, Sahai A. A comparison of sonourethrography and retrograde urethrography in evaluation of anterior urethral strictures. Clin Radiol 2004;59:736–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akano AO. Evaluation of male anterior urethral strictures by ultrasonography compared with retrograde urethrography. West Afr J Med 2007;26:102–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidenreich A, Derschum W, Bonfig R, Wilbert DM. Ultrasound in the evaluation of urethral stricture disease: a prospective study in 175 patients. Br J Urol 1994;74:93–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta N, Dubey D, Mandhani A, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Kumar A. Urethral stricture assessment: a prospective study evaluating urethral ultrasonography and conventional radiological studies. BJU Int 2006;98:149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morey AF, McAninch JW. Ultrasound evaluation of the male urethra for assessment of urethral stricture. J Clin Ultrasound 1996;24:473–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallentine ML, Morey AF. Imaging of the male urethra for stricture disease. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:361–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morey AF, McAninch JW. Sonographic staging of anterior urethral strictures. J Urol 2000;163:1070–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitterberger M, Christian G, Pinggera GM, Bartsch G, Strasser H, Pallwein L, et al. Gray scale and color Doppler sonography with extended field of view technique for the diagnostic evaluation of anterior urethral strictures. J Urol 2007;177:992–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bearcroft PW, Berman LH. Sonography in the evaluation of the male anterior urethra. Clin Radiol 1994;49:621–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman LH, Bearcroft PW, Spector S. Ultrasound of the male anterior urethra. Ultrasound Q 2002;18:123–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toms AP, Bullock KN, Berman LH. Descending urethral ultrasound of the native and reconstructed urethra in patients with hypospadias. Br J Radiol 2003;76:260–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta L, Sharma S, Gupta DK. Is there a need to do routine sonological, urodynamic study and cystourethroscopic evaluation of patients with simple hypospadias? Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:971–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berná-Mestre JD, Berná-Serna JD. Anterior urethral trauma: role of sonourethrography. Emerg Radiol 2009;16:391–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckley JC, Wu AK, McAninch JW. Impact of urethral ultrasonography on decision-making in anterior urethroplasty. BJU Int 2012;109:438–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson GG, Bullock TL, Anderson RE, Blalock RE, Brandes SB. Minimally invasive methods for bulbar urethral strictures: a survey of members of the American Urological Association. Urology 2011;78:701–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong EM, Arellano CM, Chow JS, Lee RS. Sonourethrogram to manage adolescent anterior urethral stricture. J Urol 2010;184Suppl. 4:1699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]